This chapter assesses the risks to SMEs across the Eastern Partnership posed by Russia’s war against Ukraine. First, an overview of the SME sectors in EaP countries is presented, followed by an analysis of the direct impact of the war on Ukrainian SMEs, as well as a reflection on region-wide effects, allowing for intra-regional and inter-sectoral comparisons.

Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries

4. Focus on the SME sector

Abstract

The SME sectors in EaP countries

SMEs represent up to over 99% of all firms in EaP countries. On average, they account for 58% of employment and 49% of value-added in the business sector.

Table 4.1. SMEs’ contribution to the economies of EaP countries

SMEs’ share in total number of enterprises, employment and value added, 2020

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan* |

Belarus |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total economy |

Excl oil/gas sector |

||||||

|

Nr. of enterprises |

99.8 |

99.7 |

- |

- |

99 |

98.6 |

99.8 |

|

Employment |

69 |

42 |

44 |

35 |

63 |

60 |

75 |

|

Value added |

64 |

17 |

24 |

30 |

61 |

39** |

68 |

* In Azerbaijan, excluding the oil/gas sector SMEs share of employment and value added are 44 and 24 percent, respectively

** Turnover (value added not available)

Source: National Statistical Offices of EaP countries, Georgia’s SME Strategy 2021-2025

SMEs’ contribution is particularly relevant in terms of employment generation, as shown in Table 4.1, accounting for 60 to 75% of all business-sector jobs in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. This share drops to 43% in Azerbaijan and 35% in Belarus. In terms of value-added, SMEs’ contribution is over 60% in Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine, but it drops significantly in Azerbaijan (24%, excluding the oil/gas sector) and Belarus (30%).

The picture emerging from these data is that the productive structure in Armenia, Georgia and Moldova mainly consists of small enterprises. Large enterprises play a leading role in Azerbaijan (oil and gas sector), Belarus (heavy industry and chemicals). In Ukraine, heavy industry, chemicals and manufacturing co-exist with a large population of small enterprises. Significant gaps in terms of labour productivity persist between SMEs and large enterprises in all EaP countries, with the exception of Georgia and Moldova, as the two countries do not host significant large-scale capital-intensive industries (OECD et al., 2020[104]).

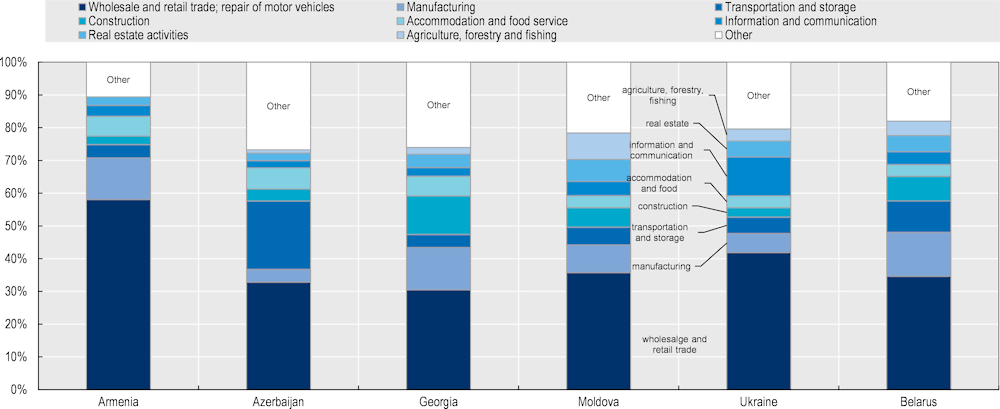

The economies of the Eastern Partner countries are characterised by a high prevalence of micro-enterprises (fewer than 10 employees) and a very limited presence of medium-sized enterprises (50-250 employees). In terms of sectoral specialisation, as shown in Figure 4.1, the largest number of SMEs across all the EaP countries operate in the service sector. Sub-sectors such as retail trade, transport and food and hospitality are densely populated by micro and small enterprises.

Figure 4.1. Distribution of SMEs by sector, 2020

Note: data for Georgia are based on persons employed by SMEs; data for Armenia do not include agriculture; “other” includes: Professional, scientific and technical activities; Water supply, sewage, waste management and remediation activities; Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; Mining; Education; Human health and social work activities; Administrative and support service activities; Arts, entertainment and recreation; Financial and insurance activities

Source: National statistical offices of EaP countries

Over the last decade, the SME population in EaP countries has gone through a process of structural change, as a result of progressive integration with the EU economic space, the impact of the national and international technical assistance programmes, in particular those supported by the EU, such as EU4Business. This is also reflected in improvements in SME performance (in Georgia, for instance, nominal SME productivity has increased by 55% between 2014 and 2019) (Government of Georgia, 2021[105]) and goes in parallel with the emergence of a new class of entrepreneurs. One of the key features is the emergence of an advanced services sector, with the establishment of new enterprises developing software and other IT services, often for foreign customers. These services are driving the growth of the information and communication1 sectors in Belarus (from 4.9% in 2016 to 7.1% of GDP in 2020), Ukraine (from 3.7% in 2016 to 4.5% in 2021), and Moldova (stable at 4.9% from 2016 to 2021), but it is also noticeable in Armenia (3.8% in 2021) and Georgia (2.9% in 2020).2

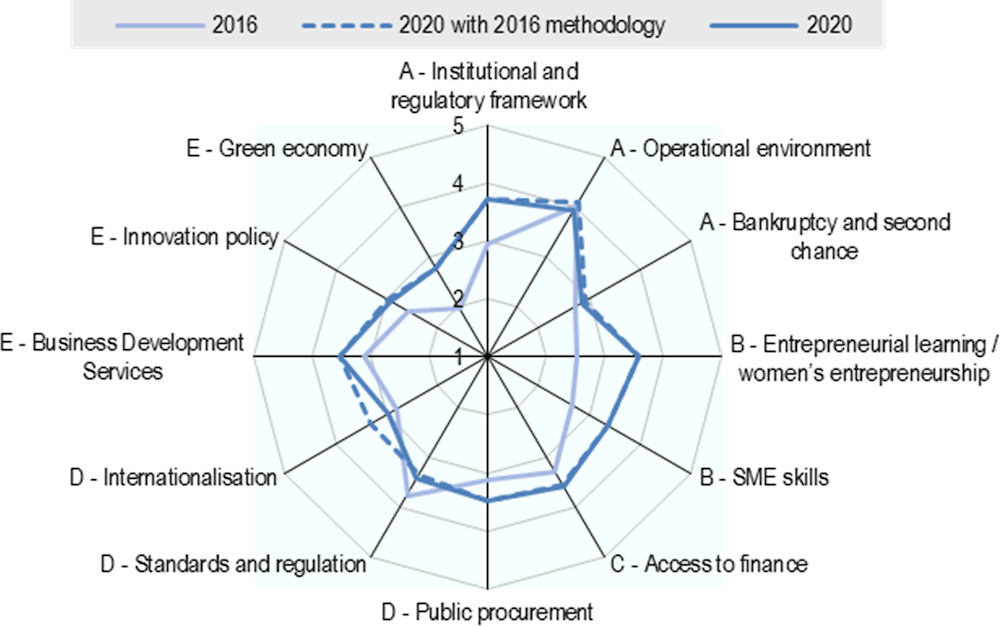

At the same time, SME policy across all EaP countries has evolved, as shown by the results of the two most recent OECD SME Policy Index assessments (Figure 4.2). Across the region, SME policy making generally benefits from stronger institutional frameworks through the design of SME strategies and the set-up of operational agencies to deliver tangible support programmes. Business-related legislation has been further simplified, e.g., by streamlining registration procedures, extending the scope of e-government services and strengthening the legal framework for insolvency. Moreover, EaP governments have increasingly developed targeted support mechanisms to enhance SMEs’ access to finance, skills and innovation. However, as in OECD economies3, SMEs across the EaP region still struggle with numerous challenges that hamper their growth and productivity. More attention should be given to establishing level-playing-field conditions for companies of all sizes and regardless of ownership structure as a precondition for market-driven private sector growth. In addition, more tailored support programmes are needed to increase productivity and enable SMEs to be competitive in export markets. Finally, governments need to strengthen their monitoring and evaluation systems4 to allow for informed SME policy making and to ensure optimal use of public resources (OECD, 2020[106]).

Figure 4.2. Progress towards SME-supportive policies in EaP countries

Note: Overall dimension scores are calculated based on five levels of policy reform, with 1 being the weakest and 5 being the strongest.

Methodological changes have been introduced to the 2020 assessment and should be taken into account when observing trends in scores. For a detailed account of methodological changes, please see the chapter “Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process” and Annex A. For an account of 2020 scores according to 2016 methodology, please refer to the relevant country chapters.

Source: (OECD et al., 2020[104])

The impact of Russia’s war on Ukrainian SMEs

The impact of the war on the SME population in Ukraine has already been massive and it is expected to deepen further as the war continues. With SMEs already severely hit by the pandemic, the war would make the recovery more difficult.

A survey of local entrepreneurs highlighted how in the first phases of the war over 40% of SMEs had ceased operations, but the situation appeared to be less critical in the summer months (16% of SMEs not working), as active military actions have been concentrated in the East and South East of the country. SMEs are trying to adapt to the challenging operational conditions, transitioning online, reducing the geography of acitvities, and resuming production at lower capacity (EBA, 2022[107]).

The main negative shocks faced by SMEs in Ukraine relate to i) the material destruction of productive capacity, ii) displaced workforces, iii) disruptions to logistics and transport systems and iv) a significant drop in domestic demand.

Material destruction is likely to have an impact on SME operations, well beyond the end of the war, and it may possibly lead to changes in the structure of the country’s productive capacity. Large energy-intensive plants, often inherited from the Soviet past, such as steel and iron manufacturing, as well as facilities producing chemicals and fertilisers, may not recover after the war, due to the lack of energy supply and the transport infrastructure. This will hit SMEs in their downstream value chains.

Conversely, the impact of workforce displacement on SMEs may be limited to the short-term, as people may progressively return to their homes once military operations have stopped, with the exception of businesses located in the cities and villages suffering a level of destruction which impedes the return of the local population. Much depends on the course of the war, since the longer people are displaced from certain places, the less likely they may be to return.

The impact of the disruption of the internal and external supply chains on SMEs’ operations is difficult to assess at this stage. Supply chains continue to operate (albeit at lower levels) in large parts of the country and may return to close to normal operations once the fighting ends, excluding the areas that have suffered the highest level of war damages. However, marine transport is blocked, and rail and road transport infrastructures are subject to heavy congestion, with long delays on land borders between Ukraine and the EU (State Fiscal Service of Ukraine[108]).

An additional risk is that a continuation of the war and the high level of uncertainty about the reliability of supplies from Ukraine may induce foreign companies to review their economic relations with Ukrainian suppliers. For instance, Ukraine plays a relevant role in the European automotive sector, producing cables and mechanical components. Shortages in components made in Ukraine is already starting to disrupt production in EU car plants. European car manufacturers have already expressed their concerns (Winton, 2022[109]).

Conversely, activity in the fast-expanding IT sector appears to be less affected. Internet connectivity and services have continued to operate through the first phase of the war, excluding in the zones affected by the most intense fighting, and staff employed by IT companies could relocate to areas less touched by the war and continue working. At the beginning of May 2022, the sector was estimated to operate at 80% of its capacity (Noyan, 2022[110]). In 2021, Ukrainian IT exports grew 36% year-on-year to total USD 6.8 billion, representing 10% of the country’s total exports. Meanwhile, the number of Ukrainians employed in the IT industry increased from 200,000 to 250,000 across start-ups, SMEs and large firms. In Q1 of 2022, the IT sector provided export earnings of USD 2 billion (+28% on the previous year). The war has caused severe disruption to the sector, but the increased international attention can unlock important opportunities for future development (OECD, 2022[111]).

However, the biggest threat to SMEs operating in Ukraine is coming from the collapse of domestic demand. With GDP expected to drop by over 30%, the loss of income may only partly be compensated by foreign aid and by a surge in remittances from Ukrainian workers in EU countries (estimated to increase by 20% in 2022) (The World Bank, 2022[112]). Domestic economic recovery, and with that the future of the SME sector, will depend very much on the size of the reconstruction plan and its timely implementation, once the war will be over.

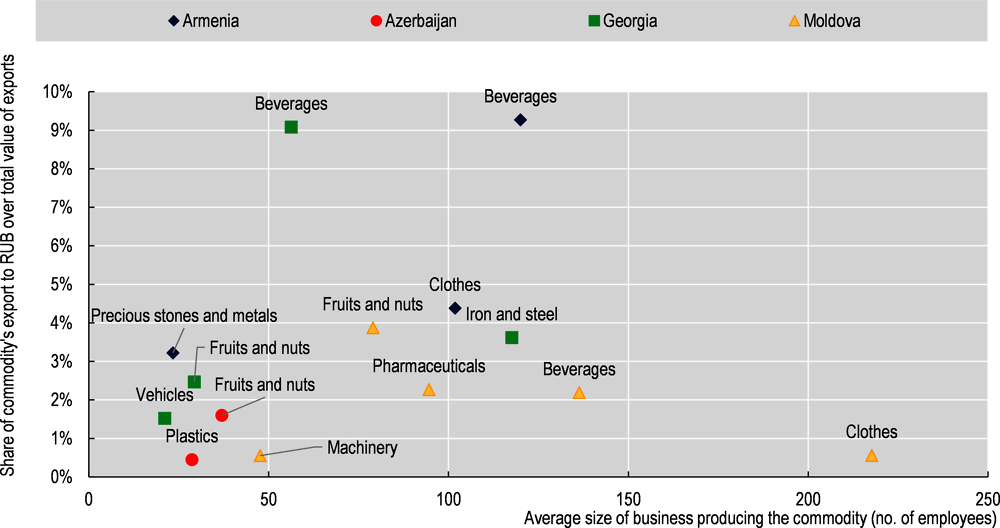

SMEs’ exposure to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus

As discussed previously, exports to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus have become much more challenging, both because of reduced demand and logistical challenges. However, not all companies are equally exposed to these risks, as some sectors are particularly reliant on exporting to the three countries involved in the war. An analysis based on trade flows and the information collected via the BEEPS database (World Bank, n.d.[113]) portrays a great deal of heterogeneity, and in particular highlights how businesses operating in some of the sectors most exposed are mostly populated by SMEs, with the average firm having have fewer than 100 employees Figure 4.3.

For example, in Armenia and Georgia, exports of beverages alone (e.g., wines and mineral waters) to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, represent over 9% of the two countries’ total exports. In Georgia, the average company operating in the sector has just over 50 employees. In Azerbaijan and Moldova, the producers of fruits and nuts export mostly to Russia and Ukraine and thus these SME-intensive industries will be severely affected.

Figure 4.3. Heterogeneous impact on SMEs in export-oriented sectors

Note: the selection of sectors considered in this analysis is determined by the match of the top 5 commodities exported by each country (excluding oil and gas) and the presence of companies operating in those sectors in the BEEPS database. The analysis based on the companies included in the BEEPS database, which does not consider micro-enterprises.

Source: (UN Comtrade[41]); (World Bank, 2021[114])

SME financing

For most firms, external financing is a necessary step to invest, grow and develop as a company. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the financing needs of many businesses, which experienced an erosion of cash flow as revenues shrank dramatically due to lockdown measures while operating costs (e.g., rents, wages, inventories) could only be partially adjusted. SMEs in EaP countries were particularly hard hit, with 70% to 90% of small and medium sized businesses experiencing decreased liquidity and cash flow since the beginning of the pandemic in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Moldova (World Bank, 2021[114]).

To respond to this, as in many countries around the world, government-sponsored rescue packages in the EaP region allowed many companies to stay afloat during the pandemic years, but they also increased private sector debt5, which may complicate further borrowing for already highly indebted businesses.

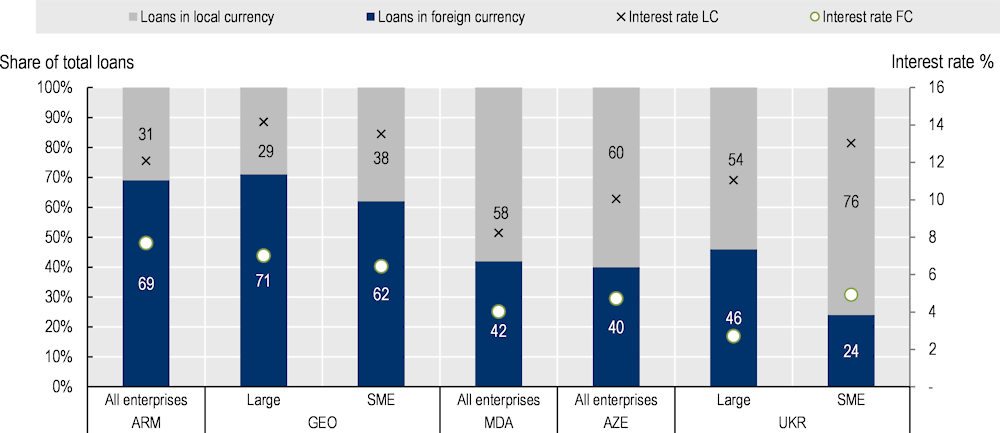

In emerging economies, a large proportion of loans is often issued in foreign currency – primarily US dollars and euros (a phenomenon referred to as ‘dollarisation’). This means that, for these loans, the principal of the loan and the repayments are denominated in US dollars or euros and have to be paid in those currencies. As the dollar and the euro are seen as more stable currencies than local currencies, lenders, especially international ones, have a preference for lending in foreign currency and demand lower interest rates. Normally, this does not pose a problem for borrowing firms. However, in times of highly volatile exchange rates, dollarisation can create difficulties in debt repayment for borrowing firms.

As can be seen in Figure 4.4., a significant proportion of loans across the EaP region are issued in foreign currency. The most dollarised countries in the region, Armenia and Georgia, both have over 60% of corporate debt denominated in foreign currency, and Moldova and Azerbaijan around 40%. The trend is less pronounced in Ukraine, which still has a significant 24% of business loans issued in foreign currency. Where data are available, one can see how debt dollarisation applies to both large firms and SMEs. In Georgia and Ukraine, SMEs have a lower level of dollarisation than large firms, though still significant. This could be because large firms rely more on international creditors for loans whereas SMEs may take loans from domestic banks and credit unions which are more likely to accept loans in local currency.

Figure 4.4. Volume and average interest rate of outstanding loans, by currency

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Central Banks of EaP countries, as of Dec 2021 (Moldova), Jan 2022 (Armenia), Feb 2022 (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine).

The effect of a large currency depreciation can be seen in the case of Georgia during 2015-16. In this period, the lari depreciated by 15% against the dollar and a recession in Russia caused a drop in the demand for Georgian exports. The result of this was a 50% increase in non-performing loans (NPLs) as firms saw the lari-value of their debts held in dollars and euros increase, while the value of their foreign currency revenue flows fell (IMF, 2021[115]).

Notes

← 1. This corresponds to section J in the NACE Rev.2 classification of economic activities, which includes Publishing activities, Motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities, Programming and broadcasting activities, Telecommunications, Computer programming, consultancy and related activities, and Information service activities.

← 2. Data from statistical offices of EaP countries.

← 3. See for example (OECD, 2019[185]), where respondents to the OECD/ Facebook/ World Bank “Future of Business” survey highlight how the state of general market conditions, innovating and accessing strategic resources such as skills and finance are the most pressing challenges for SMEs.

← 4. Useful methodological references can be found at https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/monitoring-policies.htm

← 5. For instance, domestic credit to the private sector as a share of GDP between 2019 and 2020 jumped from 21% to 26% in Azerbaijan, from 23% to 28% in Moldova, from 60% to 72% in Armenia, and from 68% to 80% in Georgia (World Bank, n.d.[72])