This chapter discusses in detail the exposure of EaP countries to the economic shocks triggered by the war through key transmission channels, such as inflation, migration, remittances, investment, and trade.

Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries

3. Transmission channels to Eastern Partner countries

Abstract

Inflation

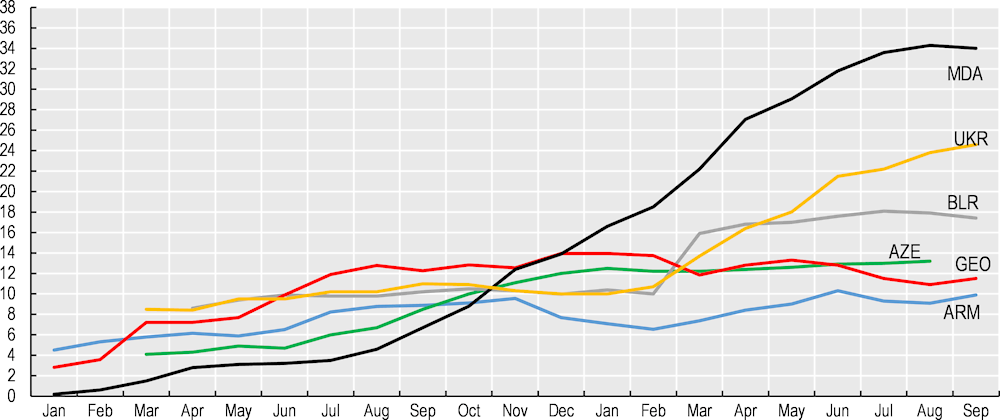

In the wake of the war, prices are soaring globally, with inflation projections for 2022 exceeding 7% for the majority of OECD countries (OECD, 2022[65]). The EaP region is no exception. While the region was already experiencing rising prices before the war, primarily due to COVID-19-induced supply problems, the war has exacerbated the existing high-inflation environment, and the depreciation of local currencies in the weeks after the start of the war made imports more expensive, adding to inflationary pressures. The combined effects of these factors are captured by the generalised increase in aggregate price levels as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Surging inflation across EaP countries, 2021-2022

Source: Central Banks of EaP countries

Table 3.1. Price increases in selected products / categories in EaP countries

% price change in May 2022 vs. May 2021

|

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

Belarus |

Georgia |

Moldova |

Ukraine |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bread |

- |

- |

- |

+35.4 |

+29.3 |

+21.4 |

|

Vegetable oil |

- |

- |

- |

+17.5 |

+27.8 |

+8.0 |

|

Fuels and lubricants |

- |

- |

- |

+49.4 |

+52.7 |

+57.5 |

|

Food products |

+13.8 |

+17.4 |

+19.3 |

+22.0 |

+32.5 |

+24.1 |

Source: Statistical Offices and Central Banks of EaP countries

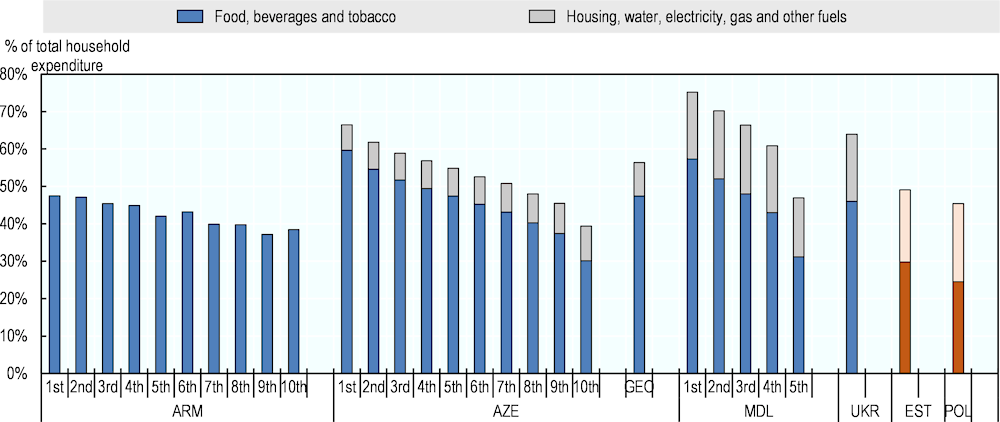

Food and energy price increases are particularly worrying. In 2020, across the EaP region, the share of expenditure on “basic” needs (food, energy, housing, water, electricity, gas) for an average household ranged from 53% in Azerbaijan (State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan, 2022[66]) to 59% in Moldova (National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova, 2022[67]). Within-country variations in income highlight how steep increases in food and energy prices are deeply regressive and can throw households into poverty (Box 3.1). In Moldova, for example, households in the highest income quintile allocate 44% of their expenditure to cover basic needs, while for low-income households basic expenditures amount to 74% of the total, a considerably higher proportion (Statistical Office of Moldova, 2022[68]).

Box 3.1. Inflation and poverty

On average, households across the EaP region allocate 59% of their total expenditure on basic goods (defined as food, housing, water, electricity gas and other fuels) and thus an increase in the price of these goods will meaningfully impact their purchasing power. Ukraine has the highest average expenditure on basic goods (64%), while the lowest is Azerbaijan at 56% (data on housing and energy expenditure for Armenia are not available, so a comparison is not possible). These proportions are significantly larger than those observed in OECD countries such as Estonia (49%) and Poland (45%).

Inflation in the price of basic goods (food and energy) threatens those on the lowest incomes in the EaP region (Figure 3.2). In Azerbaijan, the poorest 10% of households allocate 69% of their expenditure to basic goods, compared to around 40% for the richest 10%. In Moldova, the contrast is even starker, as the difference between the bottom quintile and top quintile is nearly 30 percentage points.

Moreover, across the region the proportion of expenditure on food is particularly notable, averaging 44% of total expenditure compared to 30% for Estonia and 25% for Poland. For the poorest households in these countries, this proportion can reach up to 60%. Therefore, the increase in food prices caused by the war threaten many of the poorest households with food insecurity. In 2021, the FAO estimated that, on average, 27% of people in the Eastern Partnership are moderately or severely food insecure (FAO, 2021[69]).

Figure 3.2. Inequality in expenditure on basic goods

Note: i) Armenia and Azerbaijan have information on each income decile, Moldova on each income quintile. ii) Ukraine and Georgia do not have income-decomposed data. iii) For Armenia, the classification system for Armenia refers only to food expenditure, therefore comparisons with other countries should be done with caution. Data for housing, water, electricity, gas, and other fuels are missing for Armenia.

Source: Household surveys from National Statistical Offices of EaP countries. OECD.Stat for Estonia and Poland

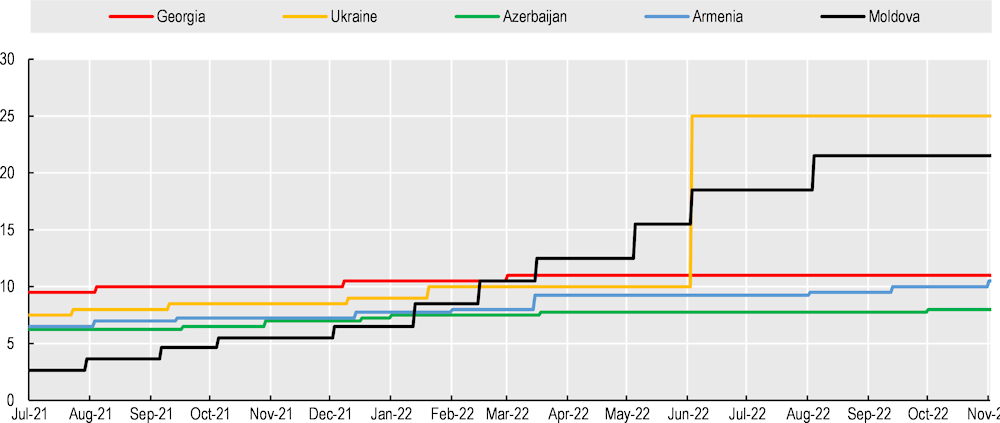

Accelerating inflation has prompted central banks in EaP countries to respond with monetary tightening. Indeed, price pressures have led to more forceful policy rate rises than suggested by earlier forward guidance in many countries, so as to minimise the risk that high inflation expectations become entrenched. Thus, while monetary tightening was already visible in 2021, central banks in EaP countries have further increased their key policy rates several times since the start of the war (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Monetary tightening in EaP countries

Source: Central Banks of EaP countries

Calibrating the scale and timing of the monetary policy changes required to steer inflation back to target ranges remains challenging, given difficulties in assessing the rate above which monetary policy becomes restrictive, the concurrent policy actions being undertaken in other countries and the speed at which tightening should occur. Clear communication about the policy stance, the key factors behind policy decisions and the expected pace of balance sheet reductions is crucial to minimise financial market disruptions (OECD, 2022[20]).

Migration

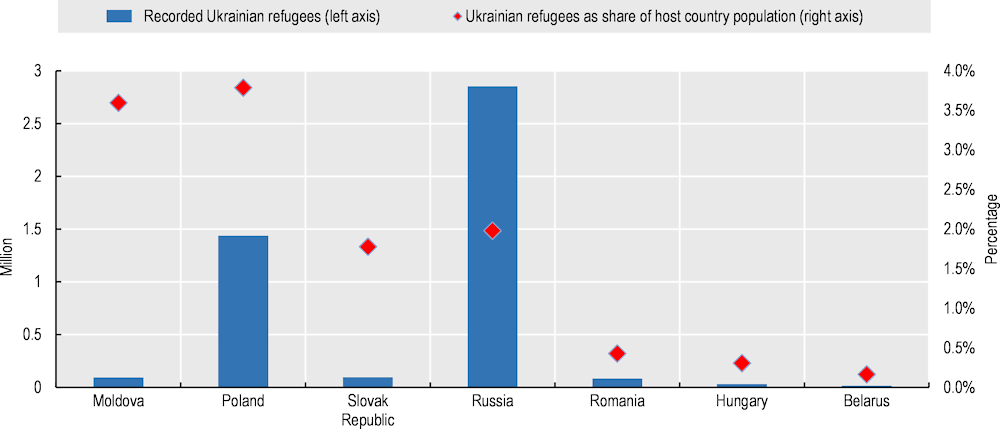

Russia’s war against Ukraine has triggered the largest displacement of people in Europe since the Second World War, with millions of Ukrainians seeking refuge elsewhere in their country or abroad. This has put unprecedented pressure especially on neighbouring Moldova. Moreover, the economic fallout from the war and sanctions have encouraged many Russian citizens to leave, with Georgia and Armenia reckoned to be among the top destinations. While this may create significant challenges in the short-term, countries can turn this into medium-term opportunities if they can capitalise on the inflow of a relatively highly skilled labour force.

Refugees in Moldova

Since 24 February 2022, more than 14 million1 border crossings took place from Ukraine towards neighbouring countries, primarily Poland, Hungary, and Romania. While return flows have also been increasing, by mid-October there were more than 7.6 million individual refugees from Ukraine recorded across Europe. Over 650 000 Ukrainians crossed the border to Moldova (UNHCR, 2022[70]). While other countries in Eastern Europe have welcomed larger numbers of refugees (particularly Poland), Moldova has received the largest inflow as a proportion of total population (25%). Around one in six Ukrainians arriving in Moldova remains in the country, while the others continue their journey to different countries (OHCHR, 2022[71]). Thus, a group equivalent to around 3.5% of Moldova’s population has settled in the country as refugees.

Figure 3.4. Ukrainian refugee arrivals

Note: data as of 11 October 2022; population data for 2020

Source: (UNHCR, 2022[24]); (World Bank, n.d.[72])

This presents a huge demand for humanitarian assistance on Moldova. The short-term needs include the creation of infrastructure to process the refugees arriving in the country, to provide decent housing facilities and to respond to food and medical needs. All of this will put additional strain on Moldova’s public finances, already put under stress by the spill overs from the war, and exacerbate the country’s external financing needs.

To respond to this, the IMF has agreed to an ad hoc review under its extended credit facility to make about USD 245 million available to Moldova (IMF, 2022[73]) and EU donors quickly pledged EUR 659 million in financial aid and humanitarian help to assist Moldova in addressing these challenges (DW, 2022[74]). The main ambition of this package is to support the weakened fiscal and economic status of Moldova resulting from the refugee crisis. The funding will be used, in part, to broaden the provision of social services and support incoming refugees. Moldova has also received support from UNHCR in processing refugees, for example through the establishment of Children and Family Protection Support Hubs, so called "Blue Dots" (Unicef, 2022[75]). Moreover, there are countless examples of private citizens and firms providing shelter, aid and jobs to refugees.

However, there are challenges ahead to integrate refugees into Moldovan society. Over 30% of refugees are school-aged children, who will need to be included into the local school system. This poses a significant problem as the language of instruction for two thirds of Moldovan schools is Moldovan. There are, however, schools providing programmes taught in Ukrainian and Russian as a result of the existing diaspora communities in Moldova. Around 6.6% of Moldova’s pre-war population had Ukrainian as a first language. Therefore, the refugee population will increase the Ukrainian-speaking population in Moldova by around 50% (Moldovan National Bureau of Statistics[76]).

Moreover, adult refugees will need to be integrated in the local labour markets. This poses a challenge for Moldova, given the limited employment opportunities available before the war. Moldova’s unemployment rate is relatively low (5% in 2019, 3.8% in 2020), but the level of economic inactivity is high and outward labour migration has long been a major feature of Moldova’s economic life (see below). ILO’s model estimates that, in 2019, only 47% of 15-64 year olds were participating in the labour force, significantly below the EaP average of 65%, and this figure has been steadily decreasing since 2000 (World Bank | ILO[77]).

Russian migration to South Caucasus

New migration patterns are emerging in the South Caucasus. The effects of international sanctions, fear of political turmoil, the risk of conscription and a deterioration in economic conditions and prospects at home are prompting many Russian citizens to move to Armenia and Georgia. While it is not yet possible to determine how “permanent” these relocations will be, surveys suggest that, between the start of the war and the end of June, over 40 000 Russian citizens had entered Georgia and were still in the country after at least one month, and 16 000 foreigners, mostly Russians, opened bank accounts in Armenia in the same period (IDFI, 2022[78]) (Central Bank of Armenia, 2022[79]).

A significant proportion of these emigrants seem to have entrepreneurial ambitions, with many working in the digital and IT sectors, as this is a more mobile industry and thus offers an easier option to work internationally. Anecdotal evidence and information from national administrations suggest a considerable number of new businesses, many of which are in the IT and digital sectors, being registered in both Armenia and Georgia: by 22 March, 268 Russian citizens had registered firms while another 938 had received official status as individual entrepreneurs in Armenia. In March, April and May, over 6 400 requests for business registrations were submitted to Georgia’s authorities – seven times more than the annual figure for 2021 (Transparency International Georgia, 2022[80]).

EaP countries have an opportunity to capitalise on this inflow of human capital and technological skill. Armenia and Georgia, which already have growing IT sectors, could bolster their tech industries and diffuse more digital knowledge into their labour market. The creation of new IT companies in the two countries could also provide additional services for firms looking to digitalise, thereby assisting with broader ambitions for digitalisation in the EaP region.

Remittances

Remittances are one of the most significant contributors to capital inflows for EaP countries. Typically, remittances are earned by a member of a family working in a different country and sending money back to the home country either permanently or on a seasonal basis. Across Europe and Central Asia, remittances flows were as large as FDI, portfolio investment and overseas development aid combined in both 2020 and 2021 (World Bank Group, 2021[81]).

Remittances often support low income households (ILO, 2009[82]). They are largely used to finance consumption of basic needs (food, housing, medicine etc.) across the region and are rarely used for saving or investment. As such, they often represent a line of support that separates these households from poverty. Without policy intervention to offer protection from generalised price increases, a drop in remittances could plunge some of the poorest in the EaP region into poverty.

In all EaP countries except Azerbaijan and Belarus, net inflows of remittances were equivalent to 10% or more of GDP in 2020. Moldova relies on a particularly large inflow of remittances, equal to 15.7% of GDP in 2020, which puts the country among the 20 most remittance-dependent countries globally (IOM, 2020[83]). Azerbaijan has a notably lower level of remittances, corresponding to only 3.3% of GDP in 2020 (Figure 3.5). However, these flows tend to be geographically highly concentrated, with the city of Lankaran receiving 33% of remittances despite constituting only 12% of the population. Therefore, for certain regions in Azerbaijan, remittances still form an important source of income (EBRD, 2007[84]). This is also the case for Armenia, where around 40% of households in the provinces of Tavush, Gegharkunik and Shirak receive remittances compared to only 20% in Yerevan (IOM, 2015[85]).

The demographic profiles of remittance workers vary across the region. For example, in Moldova, it is largely younger people who have left and are sending money back to support their parents and grandparents. In other EaP countries, such as Armenia, there is a more significant number of seasonal migrants, who go abroad for a certain period of the year and then return home. A large share of these workers go to Russia during the summer to work in the construction industry and the harvest, returning home in the latter months of the year.

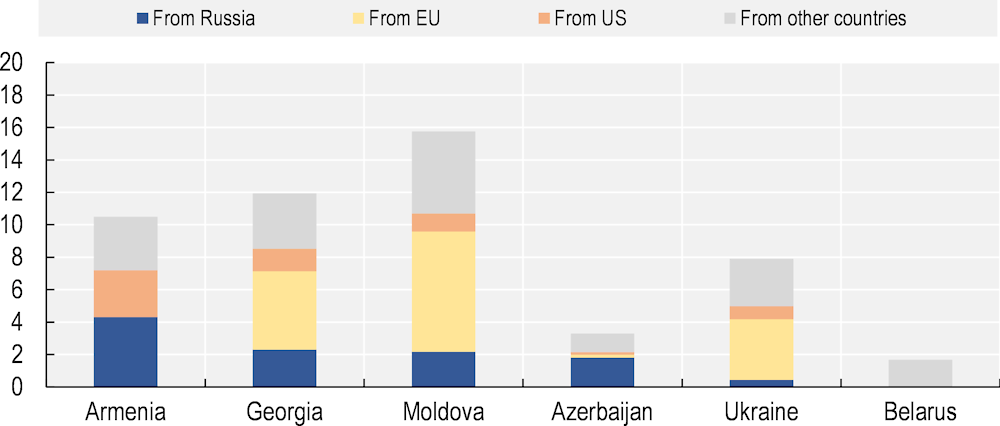

Figure 3.5. Inflows of remittances to EaP countries

Note: for Armenia, remittances from EU included in “From other countries”; for Belarus, geographical origins of remittances unspecified.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators; Central Banks of EaP countries and National Statistical Offices of EaP countries

The dependency on remittances from Russia varies significantly across the region. In relative terms, Armenia has the largest flow of remittances from Russia (4.3% of GDP in 2020), which is nearly double the size of the next largest. Georgia, Moldova and Azerbaijan all have similar exposure to Russian remittances – making up around 2% of GDP in 2020. For all EaP countries except Ukraine, there is a risk of a significant drop in remittances as a result of the war. The fact that Georgia and Moldova receive most of their inflows from EU countries does not fully shield them from the risks of a potential drop in transfers from Russia, while, at the same time, exposing them to a likely economic slowdown in the EU. However, the short-term situation is also creating a temporary exceptional inflow of Russian money to EaP countries, detailed below.

As the Russian economy shrinks due to the war and sanctions, various industries have reduced their need for labour. As a result of their more precarious position within Russian labour markets, remittance workers are disproportionately affected by this contraction; they will be the first to be laid off, and seasonal workers will not be hired. Seasonal workers in Russia have reported being asked to work off the books or not being paid at all (Mejlumyan, 2022[86]).

Moreover, there are now many practical barriers to transferring remittances out of Russia. The foreign capital restrictions imposed in Russia limit the amount of foreign currency that is allowed to leave, the removal of several Russian banks from the SWIFT payment network makes transfers more challenging, exchanging rubles exposes remittance workers to a high exchange rate risk and to significant buy/sell spreads as a result of volatility in forex markets (Saha and Staske, 2022[87]). All of these barriers make it additionally challenging to send remittances out of Russia to the EaP region.

Available data for Georgia, Armenia and Moldova shed some light on how the war is affecting remittances in the EaP region. In Georgia, remittances from Russia dropped by 16% in March (year-on-year), but subsequently saw a staggering 560% average increase in the period April-June (National Bank of Georgia[88]). For Armenia, a 291% year-on-year increase was recorded in the same period (Armstat, 2022[89]). Moldova, by contrast, experienced a 94% year-on-year drop in money transfers denominated in rubles in the period March-June 2022 (National Bank of Moldova[90]). The large influx of Russian citizens moving to Armenia and Georgia is likely to underlie the observed jump in remittances in the two countries: once arrived in the new country, Russian citizens transfer their own savings to themselves. Another reason may be the progressive withdrawal of capital of Armenian and Georgian emigrants from Russia. These factors may be compounded by the fact that, because many Russian banks are sanctioned, part of the funds that would normally be sent via the banking system are now sent via money transfer systems (e.g. Western Union, Contact, MoneyGram, Zolotaia Korona) and recorded as remittances. However, it should be noted that the more “traditional” remittances from Russia tend to peak in late-summer as a result of the seasonality of construction and agriculture, as well as migrant workers returning in Q4. Therefore, the true “structural” impact of the war and of Russia’s economic downturn on remittances flows will only be fully appreciated in the last months of the year and, even more clearly, in the coming years, as the exceptional movement of Russian citizen and capital towards the South Caucasus observed in 2022 is unlikely to continue.

Investment

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, brings a further negative shock to the world economy, with a profound and immediate impact on foreign direct investment (FDI) and other capital flows. These impacts are primarily observed in Ukraine and Russia, but have knock-on effects for regional and global capital flows through supply chain linkages and displacement effects.

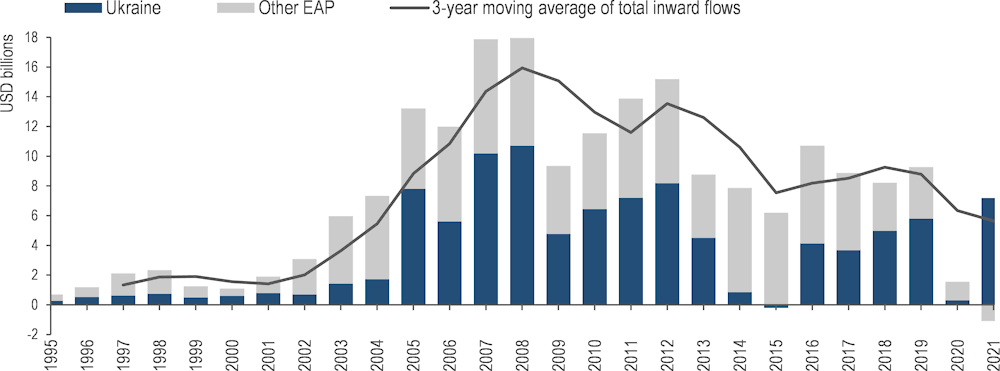

FDI inflows to Eastern Partner countries had already deteriorated as a result of the pandemic. EaP countries experienced significant contractions in FDI as a result of a series of shocks in the last fifteen years, starting with the global financial crisis in 2008-9, followed by Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, and most recently by the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 3.6). While Ukraine saw a considerable drop in FDI inflows in 2014 and 2015, FDI flows to other EaP countries rose during those years and were hardest hit by the pandemic. This suggests that the impact of the current war in Ukraine on investment flows to neighbouring countries may be moderate.

Figure 3.6. FDI flows into EaP countries

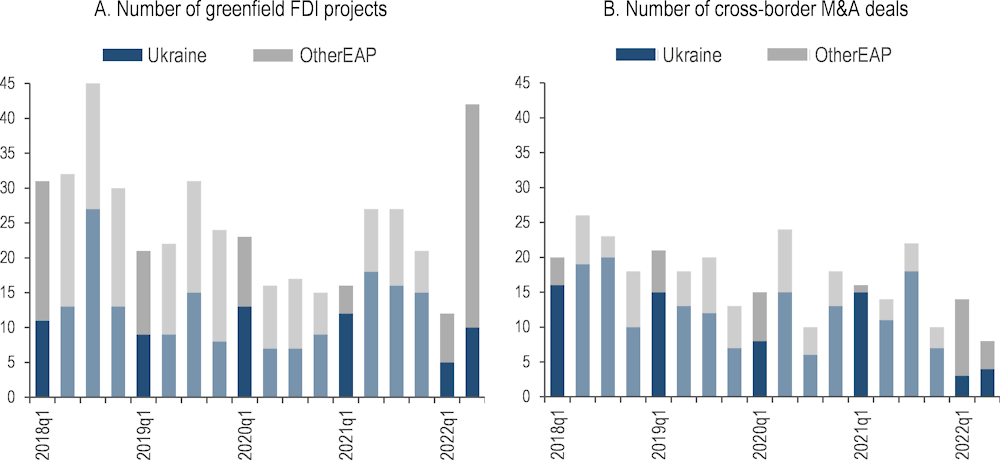

The war has had varying impacts on investment across the region. Monthly project-level information shows that the number of new foreign investment projects in the region was 68% lower in the first quarter of 2022 than the first quarter of 2018, 52-57% lower than in the first quarters of 2019 and 2020, and 41% lower than in 2021 (Figure 3.7). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) involving target companies from the region also dropped by 30% compared to the first quarters of pre-pandemic years and 13% compared to 2021. The bulk of the drop is observed in Ukraine, both in terms of new investment (-64%) and in terms of M&A flows (-81%). New investment flows to other EaP countries (excluding Belarus) were relatively higher in the first quarter of 2022 compared to 2020-2021 and only 25% lower than in pre-pandemic years, while M&A flows to other EaP countries almost tripled compared to pre-pandemic years. In the second quarter of 2022, new investment flows into Ukraine recovered somewhat, but the number of new investment projects in Armenia and Georgia increased by a factor of six, bringing the region to a peak level of new investment projects compared to previous years. This suggests that some investments that would otherwise have been made in Ukraine may have been redirected to neighbouring countries as a result of Russia’s large-scale invasion.

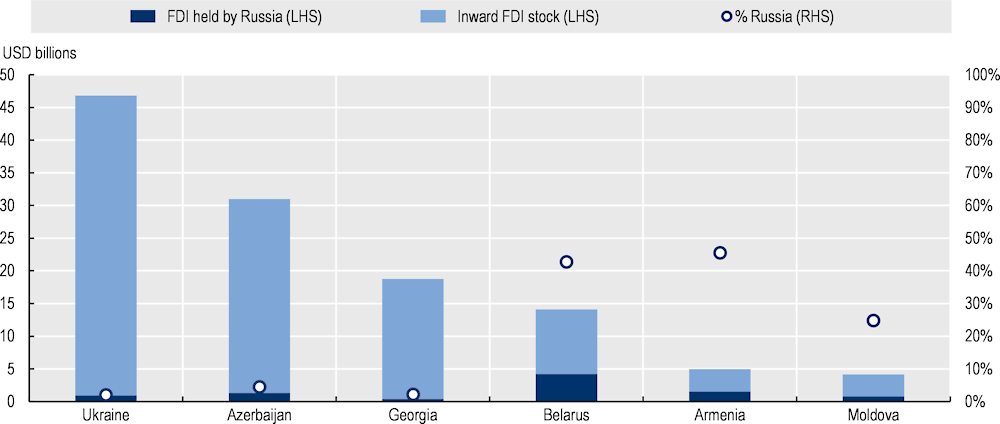

Figure 3.7. Monthly FDI flows into EaP countries

Smaller countries like Armenia and Moldova are relatively more dependent on Russian FDI. According to data on bilateral FDI positions, exposure to Russian investment varies considerably across countries in the region, ranging from 2% in Ukraine and Georgia, to 19% in Moldova and 31% in Armenia (Figure 3.8)2. While the greater dependence of Armenia and Moldova on Russian investments means greater exposure to the current political context, it also could imply that Russian-based investors will choose these countries as potential destinations to relocate their operations in order to circumvent economic sanctions.

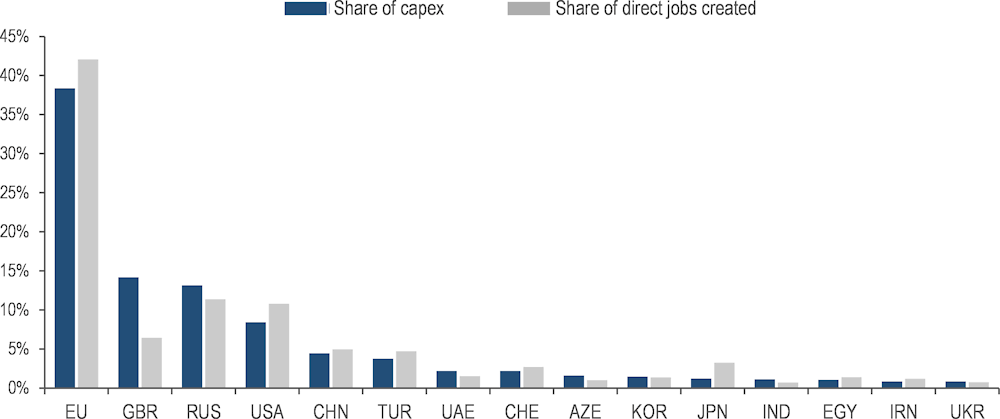

The EU is the largest source of new investment projects in the EaP region. With the exception of Azerbaijan, the EU is the largest investor in all EaP countries, accounting for 38% of the value of new investments in the region over 2003-22, and 41% of direct jobs created by FDI (Figure 3.9) . Within the EU, the top investors are Germany (8%), Austria (4%) and France (4%), although Poland and the Czech Republic are also active investors in the region (3%). The United Kingdom accounts for 14% of capital investments in the region, but only 6% of jobs created by FDI, reflecting the high capital-intensity of these investments made predominantly in Azerbaijan. Russia accounts for the second largest share of investment in the region (13%), followed by the USA (8%). Other countries with high stakes in the region include China, Türkiye, the UAE, Switzerland and, to a lesser extent, Korea, Japan, India, Egypt and Iran. Azerbaijan and Ukraine also invest significantly in the region. Among recipient countries, Georgia has the most diversified portfolio of foreign investors, receiving sizeable shares of investment from Western, Middle Eastern, North African and Asian economies.

Figure 3.8. Exposure to Russian FDI and capital flows

Note: Value reflect inward FDI positions reported by host economy.

Source: OECD based on IMF CDIS (2022[93])

Figure 3.9. New investments in EaP countries

Figure 3.10. New investments in EaP countries, by source and destination countries

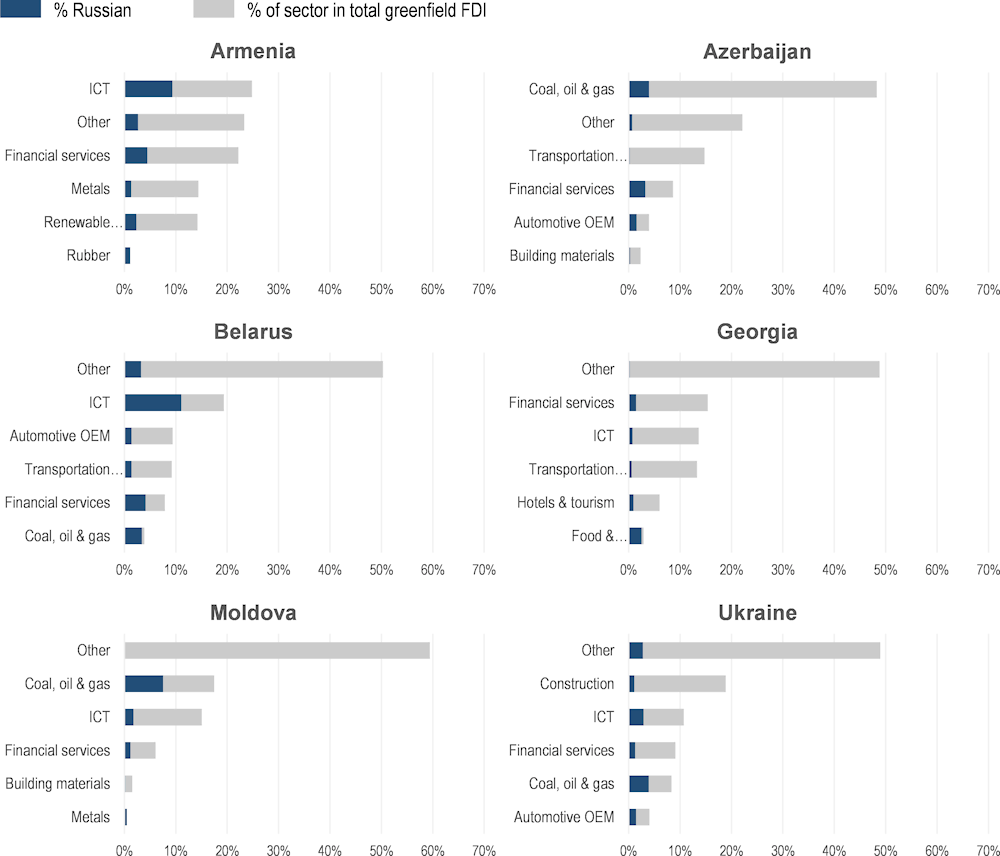

ICT and financial services are among the sectors that attract most Russian FDI in the region. The sectoral distribution of investments across the region varies by country, although some commonalities emerge (Figure 3.11). Coal, oil and gas dwarf other investments in Azerbaijan (48%) and also constitutes a sizeable share of FDI in Moldova (17%) and Ukraine (8%). Financial services tend to attract significant shares of investment in all countries, and particularly in Armenia (22%), Georgia (15%) and Azerbaijan (9%).

The ICT sector similarly attracts considerable greenfield investments in most countries in the region, and particularly in Armenia (25%), Moldova (15%) and Ukraine (11%), and a large proportion of these investments originate in Russia. Transport, tourism, and selected manufacturing activities, including metals, building materials and car parts, also attract sizeable investment shares, but to varying degrees across countries and with limited exposure to Russian investment. Manufacturing of food and beverages, a key exporting sector for Georgia, attracts investments almost entirely from Russia, and is likely to suffer significantly from the war, due to its heavy reliance on exports to the Russian market.

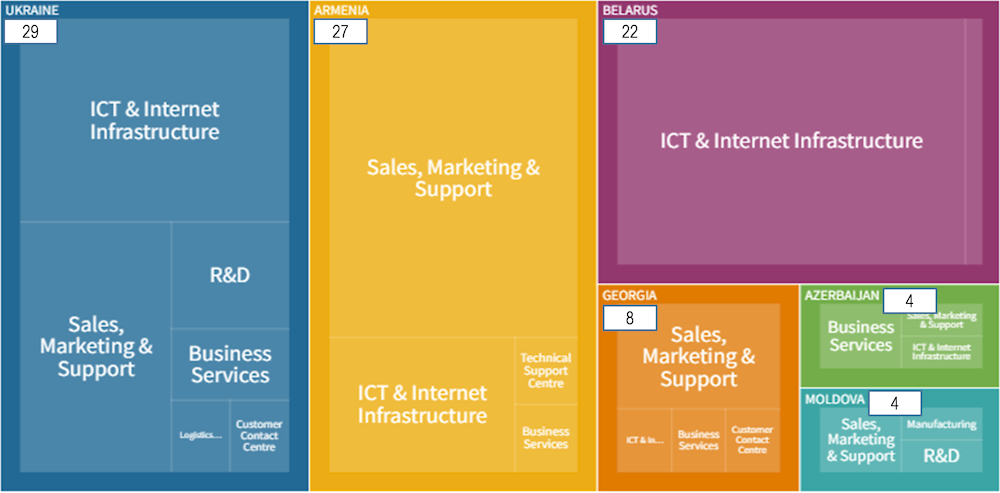

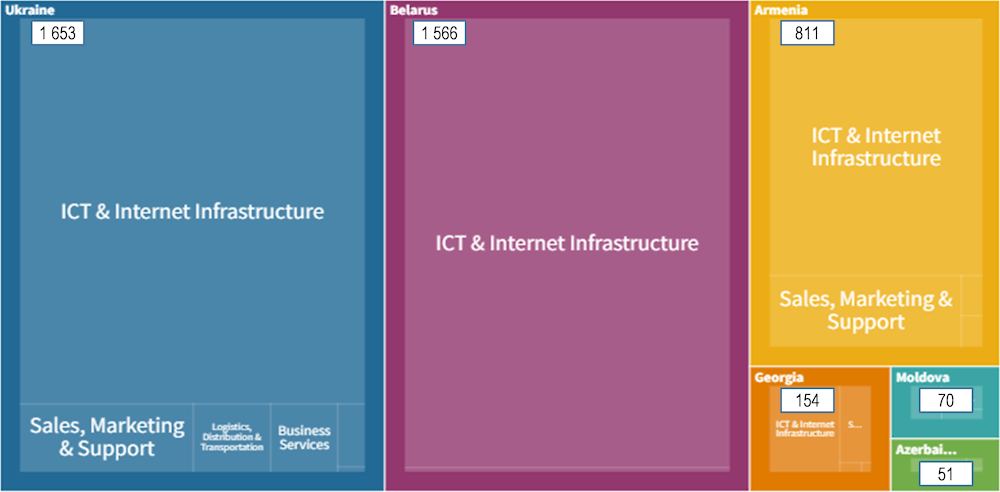

Figure 3.11. Distribution of investments in EaP countries, by top five sectors

Significant relocations of ICT companies are likely in Armenia and Georgia. Sectors with relatively low-capital intensity and high exposure to Russian investment, such as ICT, may experience an expansion in some EaP countries with more developed capabilities, such as Armenia and Georgia, due to relocations from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. This trend may be particularly relevant for Armenia, where, according to interviews with local business associations, a large migration of qualified workers from Russia was already apparent in April 2022. A closer look at Russian investments in the sector, provides a better understanding of the types of activities favoured by Russian investors in ICT in each country. In terms of capital expenditure, ICT infrastructure attracts the largest value of investments in the region, with Ukraine accounting for over 50% of all investments, followed by Armenia. These projects include investments in new data centres and extensions of wireless telecommunications coverage. In terms of volume of investments, Armenia and Ukraine are on equal footing, followed by Georgia. Sales and marketing operations attract most investors to Armenia and Georgia, while ICT infrastructure and R&D activities attract numerous investors to Ukraine (Figure 3.12).

Figure 3.12. Russian FDI in the ICT sector, by number

Note: for each country, the size of rectangles reflects the number of investment projects in each sub-category relative to the total volume of Russian investment in ICT in the EaP region (i.e. 94 investment projects since 2003).

Source: OECD based on Financial Times FDI Markets (2022[91])

Figure 3.13. Russian FDI in the ICT sector, by value

Note: for each country, the size of rectangles reflects the value of investment projects in each sub-category relative to the total volume of Russian investment in ICT in the EaP region (i.e. 4 305 USD Mln since 2003)

Source: OECD based on Financial Times FDI Markets (2022[91])

Trade

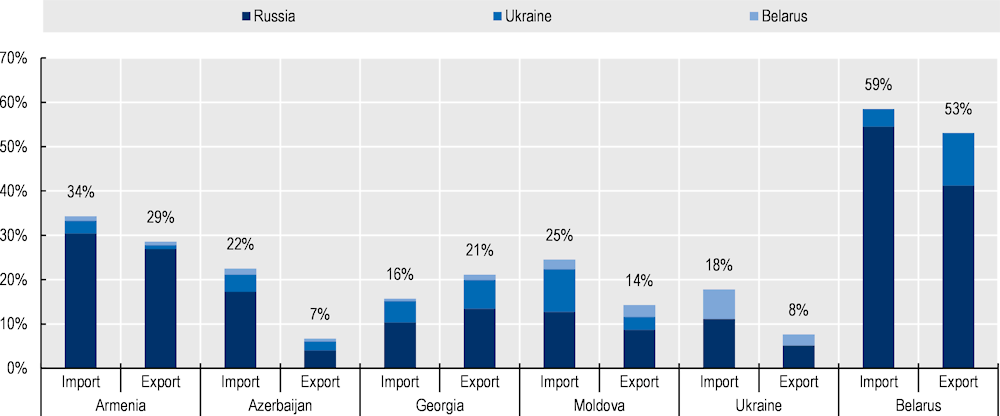

All EaP countries have significant trade relations with Russia, and some with Ukraine and Belarus. Through a combination of historical ties, geographical proximity and, in the case of Armenia, common membership of the Eurasian Economic Union, EaP countries are significantly exposed to Russia’s export and import markets. A change in Russia’s economic health, the inability to move goods through Ukraine, volatile exchange rates, sanctions and a changing international trade environment are having significant effects on all EaP economies. Further, the war is also dampening regional trade by weighing on external demand from the euro area.

Russia is consistently among the top three trade partners for all EaP countries. It originated between 10% and 54% of all goods imported by EaP countries in 2018-2021, as shown in Figure 3.14. After Belarus, Armenia has the greatest exposure to Russia, with natural gas representing over a third of the total value of imports from Russia, followed by aluminium and precious metals and gems (Armstat, 2022[94]). Georgia has a similar import profile with Russia, with fossil fuels and wheat accounting for 31% of imports from Russia in 2021. Azerbaijan’s largest imports from Russia are wheat and wood (around 23% of total import value from Russia). Moldova imports largely mineral fuels and fertilisers from Russia. Moreover, Moldova is somewhat unique in the EaP region, in that it has a strong trade relationship with Ukraine, particularly on imports of iron, wood and plastics. Since Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine has steadily reduced its trade with Russia, which in 2021 only absorbed 5% of Ukraine’s exports and originated 8% of its imports (UN Comtrade[41]). Belarus is an exception in the region with regards to its dependence on Russia, which is the source of 54% of its imports and the destination for 41% of its exports.

Figure 3.14. Trade exposure to Russia, Ukraine and Belarus

Source: UNComtrade (merchandise trade)

In terms of exports, EaP countries are generally less exposed to Russia, although it remains an important market for them. In the period under consideration, only Armenia and Belarus had Russia as their largest export market. For Azerbaijan, Georgia and Moldova, Russia was one of the top three export markets and for Ukraine it was fourth. In the last 10 years, Moldova and Ukraine have re-oriented their exports away from Russia and towards the EU (UN Comtrade[41]), further integrating within the EU economic space on the back of the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA).

However, the picture is somewhat different when one looks at trade flows at the sectoral level. Certain industries still rely heavily on Russian demand. For example, in the wine and beverage sector, prevalent in Georgia and Armenia, 43% and 77% respectively of each countries’ exports in this sector go to Russia. For Moldova, 44% of fruits and nuts exports (largely apples) and 62% of their pharmaceutical exports go to Russia3.

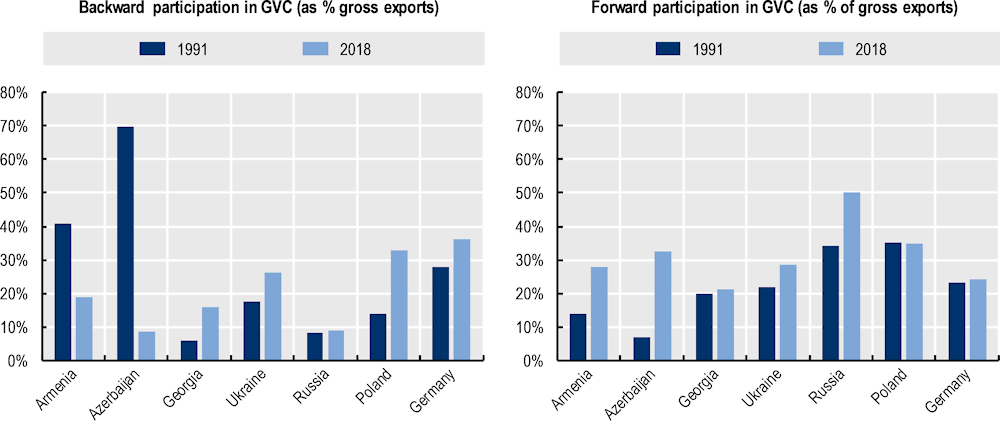

Box 3.2. EaP countries and their shifting role in Global Value Chains

Global Value Chains (GVC) have emerged as a defining feature of the world economy over the last 40 years. The international organisation of production enabled by ICTs, declining trade costs, the integration in world trade of emerging economies in eastern Europe and Asia, and the rise of multinational enterprises have all contributed to an increase in countries’ participation in GVC.

When production is fragmented across multiple countries and intermediate goods cross multiple borders before reaching consumers, traditional measures of gross exports can be subject to double-counting. To address these issues, the international community of trade researchers has developed the concept of “trade in value added”, in an effort to map GVC and better reflect where value added is produced, effectively distinguishing in a country’s export the portion of value added created domestically from the portion of value added of foreign origin, imported as intermediate inputs.

Two indicators can thus be considered for the analysis of participation in GVC:

- Backward participation: the foreign value added embodied in a country's exports

- Forward participation: the domestic value added of a country embodied in the exports of other countries

Figure 3.15. EaP countries’ participation in GVC

Source: OECD analysis based on UNCTAD-EORA GVC database (data for Belarus and Moldova not available)

Participation in GVC enables countries to specialise in areas of comparative advantage, enhancing productivity growth and supporting wages and incomes. Over the last few decades, EaP countries have experienced an important shift in the degree of participation in GVCs, reflecting the changing structure of their economies.

While increasing for Georgia and Ukraine, EaP countries still exhibit lower levels of backward participation in GVC than more advanced OECD economies such as Poland or Germany. This is partly due to the lower sophistication of their manufacturing output that can be exported and requiring foreign components as intermediate inputs. The low values of exports for Armenia and Azerbaijan in the early 90s contribute to explain the evolution in both backward and forward linkages for the two countries: increasing exports of commodities extracted locally have reduced the relative contribution of foreign value added, while they have caused their forward participation to jump since energy and minerals (e.g., copper) serve as inputs in partner countries’ production.

The war in Ukraine is disrupting trade through four main channels: reduction in demand in target markets, sanctions against Russia, capital flow restrictions introduced by Russia and increased transport and logistical costs.

As noted above, Russia’s economy is projected to contract by around 4% in 2022, while Ukraine’s is forecast to shrink by over 30% (EBRD, 2022[97]) (IMF, 2022[98]) (World Bank, 2022[21]). This economic crisis will translate into lower demand for EaP exports, as Russian consumers and firms have less available income to spend while exports to Ukraine suffer from both the recession and logistical challenges associated with getting goods in and out of the country. Therefore, EaP countries are likely to experience a significant fall in demand for exports in these markets with a disproportionate impact for the most exposed sectors. In particular, the impact of a contraction in Russia’s economy will be more pronounced on those sectors that are more responsive to changes in income. For example, wine is likely to be affected as people tend to forgo leisure goods if they are concerned about their incomes, whereas other goods, such as basic food items, have a more robust demand that is relatively invariant to income changes.

Ukraine’s contraction has more of a concentrated impact on certain sectors in, primarily, Moldova. Ukraine is one of the top three importers of Moldovan fruits, iron and steel, therefore in these sectors the impact of Ukraine’s economic contraction will be more severe (UN Comtrade[41]).

The removal of many Russian and Belarusian banks from the SWIFT messaging system means that these banks encounter practical obstacles when trying to transfer assets abroad. Payments for imports are thus being delayed. Local sources in the EaP region have verified that numerous exporting businesses work on consignment, shipping goods to their clients under a promise of payment upon delivery. As the war continues, this will become an increasingly challenging way of doing business, putting pressure on firms’ liquidity and ability to access credit.

Russia has imposed several capital controls in an effort to prevent the further depreciation of the ruble. These include restricting the amount that Russian citizens and firms can transfer overseas to USD 50 000 per month (with certain firms now exempted from these restrictions). Anything above this amount, if requested in US dollars, is dispensed by banks in rubles. As the majority of international trade is conducted in dollars or euros, this restriction makes it complicated for exporters to Russia to receive payments. This compounds the effect of the sanctions on Russian banks and is more widespread – affecting all Russian firms and citizens.

Finally, transport and logistical costs have increased as a result of the war. High energy prices have increased the cost of all forms of transport. Air transport has become slower and more expensive as a result of the closing of the airspace over Russia and Ukraine, which makes it more difficult for the South Caucasus region to trade with Europe. Sea transport has become more challenging for the region, due to Russia’s blockade of Ukraine’s ports on the Black Sea, with many severely damaged by the Russian army. This makes it near impossible for anything to get out of Ukraine by ship, also adding an additional level of difficulty for Moldova, which has lost access to its shortest route to the Black Sea through Ukraine. For Georgia, sea transport now has additional risks as a result of the war. The effect of this can be seen through the cost of insurance for cargo ships crossing the Black Sea (Koh and Nightingale, 2022[37]). This also affects both Armenia and Azerbaijan, which transit a significant proportion (or all, in the case of Armenia) of their goods through Georgia. The effect is an overall increase in the price of EaP exports, making them less competitive internationally. This may have an impact on EaP countries’ existing trade relations, as well as making it more challenging to attract new trading partners,

Overall, three simultaneous effects should be considered to fully appreciate the impact of the war on EaP countries’ exports (Movchan, Giucci and Staske, 2022[99]):

An income effect. Recession in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine will mean lower incomes and thus reduced demand for goods exported to these countries. This dynamic will be at play beyond the EaP region since global slowdown and surging inflation will also dampen disposable incomes across the world.

A substitution effect. Russia and Belarus could potentially turn to EaP countries for goods that are no longer being provided by the western economies that have imposed sanctions. This dynamic could also apply to EU economies, which, having dramatically reduced their imports from Russia and Belarus because of international sanctions, may now turn to EaP countries to source certain inputs. This is the case of energy imports for Azerbaijan, for example.

A reorientation effect. EaP countries could try to compensate for the reduction in exports to Russia and Ukraine by diversifying their trading partners and start exporting to alternative markets. However, this option will be hampered by the increased transport costs discussed above.

Preliminary signals from Georgia’s export performance since the start of the war support this4. While Georgia’s overall exports increased by 33% in March-August 2022 compared to the same period of the previous year, export flows to Ukraine contracted (-21%) and those to Russia stagnated (+3%) compared to other major markets (+105% to Armenia, +58% to Türkiye, +17% to Azerbaijan, +11% to China). Correspondingly, when comparing average monthly trade flows since the start of the war (March-August) with the same period of the previous year, exports in some of the most exposed sectors in Georgia mirror the negative trend: exports of wine decreased by 7%, mineral waters by 41%, pharmaceuticals by 14%. As industrial activity in Russia contracts, demand for Georgian manganese is expected to be severely affected (although preliminary data for the first half of 2022 shows how Georgia’s ferroalloys are able to find alternative markets, such as Kazakhstan and the United States) (National Statistics Office of Georgia, 2022[100]).

Armenia’s exports to Russia fell by 21% y-o-y in March but rebounded in April (+34%) and have continued to grow steadily on the back of high commodity prices and a double-digit depreciation of the dram against the ruble for a considerable part of the year (Statistical Committee of Armenia, 2022[101]).

In Moldova, after a strong recovery in 2021, exports further increased by 72% in the first half of 2022, mainly driven by the agri-food sector (cereals and oil seeds), and due to high prices and record harvest in 2021. Exports to Russia, however, are on a negative trend and have contracted by 9% in the first half of 2022 (NBS, 2022[102]).

In Ukraine, the impact of the war on trade flows has been dramatic. The strong export growth observed in January and February (+57 and +20% y-o-y, respectively) has reversed to a year-on-year fall in exports of 52% in March and April, a trend that has continued over the summer months (-49% in May, -40% in June, -48% in July, -47% in August) (NBU, 2022[103]).

Notes

← 1. As of 11 October 2022. The total outflow from Ukraine presented as border crossings from Ukraine (since 24 February 2022) reflects cross-border movements (and not individuals).

← 2. In practice, Russian investment in the region may be higher than shown by bilateral FDI statistics since Russian investment is often re-directed through Cyprus and other countries with favourable tax regimes.

← 3. Data from (UN Comtrade[41]) for the period 2018-2021.

← 4. The large swings observed in the price of many commodities in 2022 may act as confounding factors in the analysis of trade data. While nominal trade flows, expressed in monetary terms, may appear to have jumped dramatically in some cases, the growth in volume terms may be substantially lower. For example, the export of ferro-alloys from Georgia to Turkey in Jan-Sep 2022 grew by 51% year-on-year in value, while the growth in volume was only 7%. With this in mind, the analysis presented in this section is based on the only data broadly available at the time of writing, expressed in nominal terms.