Henry Ford was famously unenthusiastic about history (Swigger, 2014). Thus we might airbrush from history that the Ford Model T, produced from 1908 to 1927, was an original flex fuel vehicle (FFV), being able to burn gasoline or ethanol. Or the fact that Ford produced a prototype car with bioplastic panels in 1941. The dominance of the internal combustion engine was settled with the conventional oil discoveries in the Middle East.

Some other pertinent lessons from history are directly related to the consumption of fossil resources. First, the fossil era ushered in a lifestyle unimaginable by many at the start of the 20th century. By mid-century, fossil resources began to shape and re-shape geopolitics. As the century began to wind down the complications of societies reliant on fossil resources began to emerge. By century end, the implications of weaponisation of fossil fuels and conflicts, and proof of climate change, had started the search for alternatives.

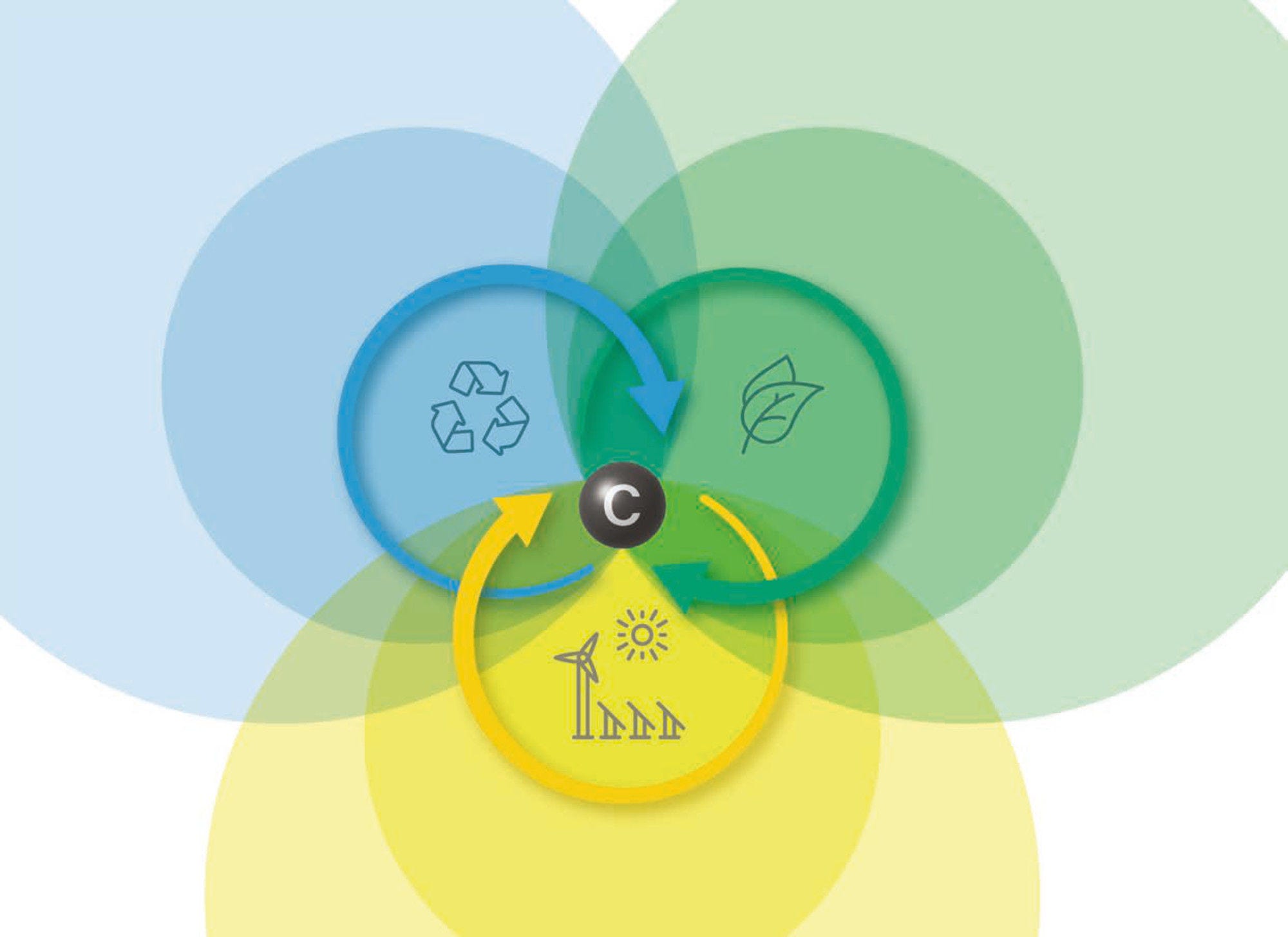

A more even distribution of renewable material and energy could change these dynamics. However, it is important that countries and their governments back new technologies to prevent being left behind. The transition is not simply all countries getting behind the climate crisis but is also about the other far-reaching social and environmental challenges identified. Planetary boundaries, a term born this century (Rockström, 2009) but still buried in the arcana of its professional cadre, may become mainstream as we learn to live within those boundaries.