Landry Signé

Thunderbird School of Global Management, Brookings Institution, and Stanford University

Development Co-operation Report 2023

2. Development Strategies in a changing global political economy

Abstract

The increasingly complex and polarised global landscape calls for more agile and effective development co-operation strategies. Developing countries are demanding reform of the global financial architecture, pushing traditional development actors to not only rethink development co-operation but also to truly understand why traditional development assistance and co-operation have not produced their desired outcomes. Partnerships must become more responsive to local conditions and needs, consider inequalities in access to development finance, and aim to restore trust in multilateralism. This chapter explores the problems, politics and policies that have set the stage for a potential new paradigm of development, one in which developing countries can leverage the growing competition among development actors to ensure that they have full agency to determine their own development pathways.

The author would like to acknowledge editorial work and assistance from Daniela Ginsburg, Hanna Dooley and Holly Stevens.

Key messages

Rising geopolitical tensions and competition among development actors have increased polarisation and pose risks for international co-operation. They also present opportunities for developing countries to choose and design the partnerships that best suit their needs and to demand a greater say in charting their development pathways.

Development co-operation cannot be successful if it tries to apply old methods to the new and increasingly complex challenges of today. Instead, it must be based on strategic co-ordination that leverages the strengths of each player, including the multilateral system, with developing countries in the driver’s seat.

Beyond a paradigm shift, successful implementation – often the major barrier to achieving development outcomes – is key. New strategies must consider the domestic political economies of all development partners and tailor implementation strategies accordingly.

There is no doubt that international development co-operation is shifting as conflicts, emerging players, health and climate crises, and economic uncertainties reshape today’s global geopolitical landscape. Tensions between major global players around economic, security and geopolitical issues are disrupting the global economy and increasing polarisation. This trend poses substantial risks for development as rising competition distorts incentives and instrumentalises development finance (Jones, 2020[1]). Yet polarisation is also providing opportunities – for recipient countries to defend their own interests and goals with more options and for regional organisations to play a more prominent role. To make progress where possible, the development community will have to adjust strategies to account for these dynamic changes (Bradford, 2022[2]). If the development community is better equipped to operate within complexity, it can take advantage of areas of mutual interest that, if acted on, can unlock desperately needed development outcomes.

In this context, what challenges do traditional development actors face and how can they best meet these? What opportunities are emerging in the shifting landscape for both donors and recipients, and how can these be turned into actionable strategies to meet ambitious development goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

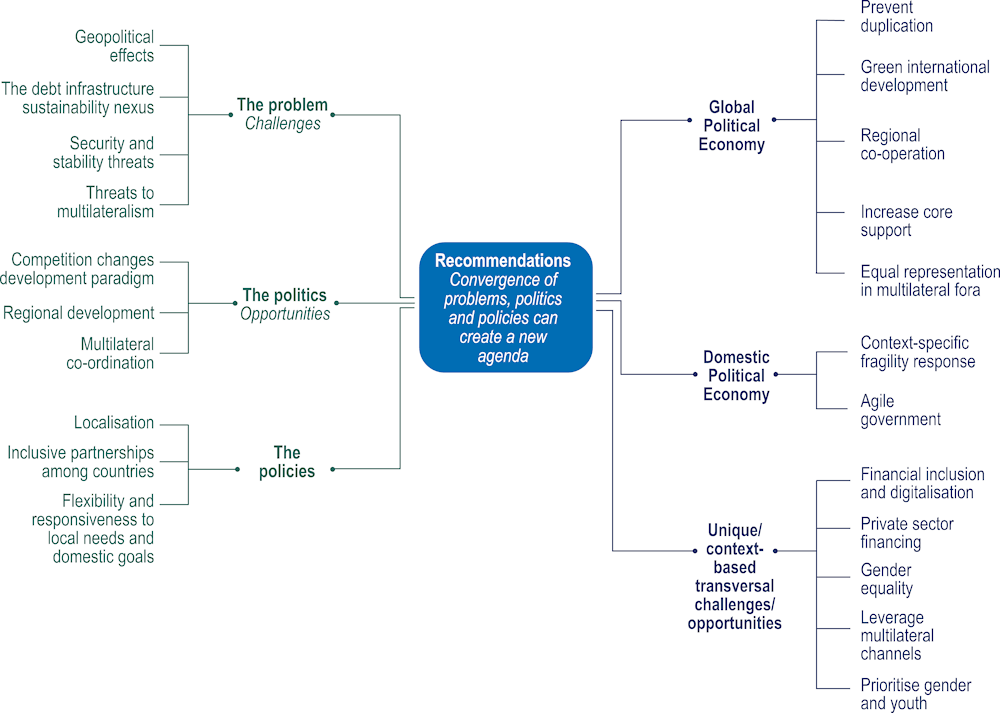

This chapter surveys the current field of global international development co-operation through the lens of the policy framework developed by Kingdon (1984[3]), which holds that when three streams – the problem, the politics and the policies – converge, an ideal window of opportunity opens for new policies to be put on the agenda and adopted (Figure 2.1). It identifies the challenges (the problem), opportunities (the politics) and recommendations (the policies) that are most relevant to the goal of lasting and sustainable socio‑economic development and inclusive poverty reduction. Of course, policies must not only be crafted but also implemented, and the implementation gap between development intentions and outcomes remains a serious and ongoing concern. Thus, this chapter also uses the conflict-ambiguity model of political economy introduced by Matland (1995[4]) as a tool for conceptualising why certain development policies succeed or fail when new development paradigms are implemented.

Figure 2.1. The convergence of problems, politics and policies offers a rare window of opportunity

Recent global shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine have confirmed that the world is increasingly interconnected and more complex than ever before. Increased digitalisation, the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and its emerging technologies, climate change, migration, financial crises, and other shifts all create opportunities and challenges that reach beyond borders. Without international co-operation, it is impossible to fully seize these opportunities and unblock barriers. At the same time, the worldwide rise in nationalist populism and the backlash against globalisation are signs that countries are turning inward and retreating from international co-operation efforts.

While the current context presents new risks, even before their advent, development goals were not being met. There still are countries facing instability, hunger and extreme poverty despite genuine efforts by the development community to find and implement solutions. This has led to calls to better understand why traditional development assistance and co-operation have not produced their desired outcomes (Mélonio, Naudet and Rioux, 2022[5]). The current global shocks have exacerbated existing vulnerabilities within countries and between development actors, making development sector reform top of mind for recipient and donor countries, multilateral organisations, think tanks, non-governmental organisations, and development banks.

Nonetheless, opportunities to forge a new development agenda are emerging. There are recent examples of the three streams – the problem, politics and policies – converging in the development sector, among them the recent agreement at COP 27 to create a dedicated climate change loss and damage fund (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2022[6]) as well as the ongoing adoption of the localisation agenda by mainstream development actors. The same geopolitical tensions and other political factors that inhibit development co-operation can, and often do, prevent convergence if they sap political will and pull major powers out of alignment on the urgency of identifying and resolving problems. But the window of opportunity is still open for a paradigm shift in the development sector, especially among recipient countries.

The problem: Challenges to international development co-operation

The first stream involves actors identifying the importance of an issue or a problem as the result of either a major event or overall increased attention to a subject. In the case of development co-operation, this first step is already underway: Development actors, both recipients and donors, have recognised the need to redefine development in response to a multitude of factors. Global shocks have highlighted the need for co-operation, as have more gradual but persistent trends such as rising inequality and social unrest. These factors have led to mounting pressure from civil society and recipient countries and from within development institutions themselves to seek change in how development is structured, co-ordinated and implemented.

To stay relevant and adopt a new, more effective agenda, the development sector must understand the impacts of the current context on development co-operation efforts and the challenges presented by geopolitical tensions, global shocks, and overall global economic and political trends.

Geopolitical effects

Over the past two decades, global trade dynamics have shifted tremendously. Before 2020, 80% of the world’s countries traded more with the United States than with the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”). This percentage has since flipped. In 2018, just 30% of countries traded more with the United States than with China, and China was the top trading partner for 128 out of 190 countries (Ghosh, 2020[7]). Escalating tensions between China and the United States over other economic and security disagreements have increased polarisation and led to higher tariffs and trade wars, with disruptive effects globally (Signé, 2018[8]; 2021[9]), including global trade diversion and supply chain disruptions (Fofack, 2022[10]). The pandemic further exacerbated trade disruptions as world trade overall declined (Signé and Heitzig, 2022[11]). The trade war between China and the United States is estimated to have cost 0.5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) (Fofack, 2022[10]), with greater losses in countries and regions that are more dependent on commodities and trade. For example, in Africa, the trade war is estimated to have caused a 2.5% decrease in GDP for resource-intensive African economies (Fofack, 2022[10]), affecting domestic and international development priorities. But polarisation has offered emerging countries more opportunities to host manufacturing plants and jobs as high-income countries move manufacturing out of China to countries and economies such as Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Chinese Taipei and Viet Nam.

Geopolitical tensions and competition are also affecting how, how often and with whom countries engage when it comes to development partnerships. For example, trade between the Russian Federation and African countries increased significantly in 2022 (Aris, 2022[12]), and the United States and the European Union (EU) have explicitly cited the Russian Federation’s widening influence in Africa as a driver of their new development strategies there (Chadwick, 2022[13]). Polarisation and competition can lead countries to focus on narrow national interests or to pursue geopolitical dominance, neither of which aligns with human rights, sustainability, or the overall social and public good goals of development co-operation.

The debt-infrastructure-sustainability nexus

Infrastructure is primarily financed by debt in developing countries, where 70% of infrastructure projects will be undertaken by the public sector and 70% of those will be financed by debt (Kharas, 2021[14]). There are three main sources of lending: 1) official financing from multilateral institutions and bilateral Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors; 2) semi-official financing by state-supported banks such as the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank, which have financed Belt and Road Initiative projects, as well as the India Exim Bank and other financial institutions in major emerging economies; and 3) sovereign borrowing from global capital markets (Kharas, 2021[14]). The options for developing countries seeking financing are to either go to global markets, where their borrowing costs are higher than for wealthier economies, or rely more on official development assistance (ODA) of regional development banks (Spiegel and Schwank, 2022[15]).

The SDGs, meanwhile, have linked climate change and development co-operation by emphasising the need for sustainable infrastructure and power. While certainly crucial to curb carbon emissions, the push for sustainable investments has increased upfront costs for infrastructure options in developing countries, thus “biasing liquidity-constrained countries to adopt least-cash solutions rather than least-cost solutions in their infrastructure choices” (Kharas, 2021[14]).

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected investment and financing options for developing countries, making investment trade-offs even more burdensome. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has become more volatile, for example: it decreased by 42% in 2020, increased by 77% in 2021 (UNCTAD, 2022[16]) and is expected to drop by an additional 23% in 2022 (OECD, 2022[17]). Higher inflation and borrowing costs squeeze the fiscal and macroeconomic space to enact necessary changes in monetary policies, limiting not only financing options but weakening their ability to absorb the shock of rate increases (Ha, Kose and Ohnsorge, 2022[18]; Gill, 2022[19]).

Countries’ economic recoveries in the wake of the pandemic show the global inequalities in accessing financing and in borrowing costs. Advanced economy governments have the privilege of borrowing in their own currencies while developing countries cannot. Developing countries face more constraints, not only in the wake of the pandemic but in their borrowing overall. The interest cost for developing countries is three times higher than for developed countries, and least developed countries allocate an average of 14% of their GDP to interest payments compared to only 3.5% for developed countries (Spiegel and Schwank, 2022[15]). The cost of debt diverts more funds away from public investment and makes it more difficult for developing countries to plan long term.

Least developed countries allocate an average of 14% of their GDP to interest payments compared to only 3.5% for developed countries.

In the wake of global crises, many countries have seen their long-term foreign currency sovereign credit rating downgraded, further aggravating an already vicious debt cycle and highlighting persistent barriers to financing for developing countries. Negative warning announcements from rating agencies are associated with increases in the cost of borrowing – 160 points versus 100 basis points for advanced economies (Spiegel et al., 2022[20]). Sovereign ratings are also vulnerable due to their more subjective nature compared to corporate rating methodologies (Spiegel et al., 2022[20]). Rating downgrades have also been shown to have a statistically significant negative effect on FDI levels (Mugobo and Mutize, 2016[21]). For example, Ethiopia, one of the most indebted economies in Africa, faced mounting obstacles to meeting its debt obligations, including low returns from externally financed projects, a foreign currency shortage and the immediate need to deploy funds for pandemic recovery (Berhane, 2021[22]). When the government announced the country was requesting debt treatment under the Common Framework, creditors reacted by downgrading Ethiopia’s rating. This increases the cost of servicing its existing USD 25 billion debt as investors request higher interest rates for lending, making Ethiopia’s debt situation even more dire (Berhane, 2021[22]).

Security and stability threats

Violence and other threats to stability have increased over the past decade, hindering developing countries’ progress. Conflict-related deaths in Africa increased almost tenfold from 2010 to 2020. In 2020, the World Bank classified 6 African countries as having high institutional and social fragility, and 14 others were engaged in medium- or high-intensity conflicts (Fofack, 2022[10]). Climate change has also exacerbated conflicts and fragility in regions already at risk, such as the Sahel (Mbaye and Signé, 2022[23]).

The increase in violence and fragility presents various challenges for development actors (Signé, 2019[24]) as governments in contexts impacted are forced to divert funds from various development priorities for military expenditures (Fofack, 2022[10]; Ndulu et al., 2007[25]). Instability also creates more incentives for governments to prioritise short-term alleviation and less ability to focus on and invest in long-term goals.

Threats to multilateralism

The rise of polarisation and of countries turning inward severely undermines the critical role of multilateralism – a particular danger when populist parties are on the rise. Without strong multilateral, regional or global institutions working towards a common goal, progress can be constrained or reversed when there are large political swings in individual countries. Polarisation undermines the ability to reach a consensus on global issues. As China and the Russian Federation become more assertive in multilateral bodies and the United States returns to these bodies after the previous administration’s unilateralist agenda, polarisation is causing the foundational liberal principles of multilateralism to be challenged (Moreland, 2019[26]). Multilateralism is viewed with increasing scepticism, with multilateral efforts seen less as beneficial and more as undercutting national interests. The multilateralism of the traditional post-Cold War multilateral order cannot be relied upon to solve challenges today and will not lead to convergence on the problem, politics or policies regarding how development actors function in the future. Finding consensus is increasingly difficult as advanced economies use soft power for influence, including for votes and support within existing multilateral institutions. Consensus may be even more difficult as polarisation increases, meaning multilateral approaches must adjust to new parameters that include power competition to achieve its goals (Moreland, 2019[26]).

Funding dynamics within multilateral institutions also contribute to undermining their reputation for being collaborative and fair. In 2018, 36% of all multilateral funding came from just 3 of the 193 United Nations (UN) member states – Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States (Silva, Bernardo and Mah, 2021[27]). In 2020, DAC members accounted for 81% of the total funding within the UN development system (OECD, 2022[28]).

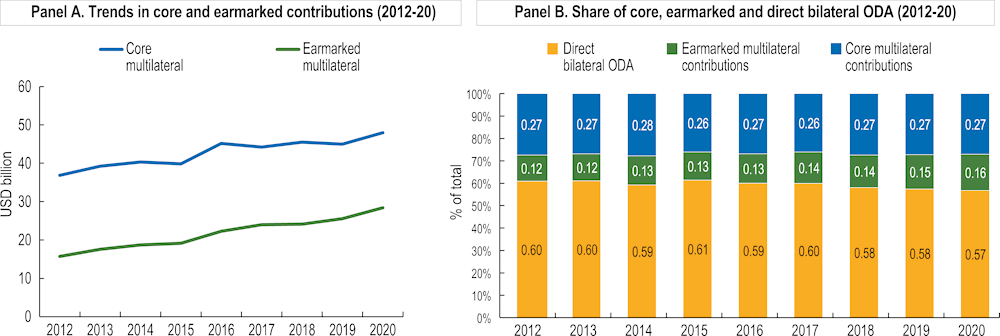

Internal vulnerabilities also threaten the effectiveness of multilateralism. A growing share of donors’ funds are earmarked for specific purposes without sufficient consent or collaboration (Figure 2.2). Increasing shares of earmarked funds can partially be explained by the increase in urgent needs over the past several years. Yet earmarking contributes to instability, as political or economic changes in DAC member countries can lead to an abrupt reduction of funding, putting projects, especially long-term ones, at risk.

Figure 2.2. Earmarked funding represents a growing portion of multilateral development finance

Source: OECD (2020[29]). Multilateral Development Finance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e61fdf00-en.

The politics: Geopolitical competition also presents opportunities for development

Within the challenging current context and despite geopolitical tensions, there are also opportunities to be seized that could be beneficial for development reform in the long run. These recent geopolitical developments and tensions have had a significant impact on international co-operation in terms of the types of countries that are engaged as donors (Kharas, 2021[14]; Signé, 2018[8]). The growth of South‑South co-operation has challenged the narrative of the traditional donor-recipient relationship, as middle-income countries such as China and India begin to take more control over development (Signé, 2018[30]; Silva, Bernardo and Mah, 2021[27]), with China, in particular, contributing many development initiatives (Klingebiel, 2021[31]).

The division between what some term “the West and the rest”, (the “rest” being China and the Russian Federation, in this context) has provided an opportunity for middle powers such as Australia, India and Japan to expand their influence in development (McCaffrey et al., 2021[32]). Collaboration between new and established actors leads to new types of partnerships where the unique strengths of each can be leveraged in a powerful way. For example, in Asia, more traditional donors such as Australia, Germany, Japan and the United States can draw on their history of development assistance to provide resources and knowledge, while newer donor countries such as Korea can provide the regional knowledge and experience that come from being closer geographically, economically and historically to the recipient countries (Ingram, 2020[33]). These new alternative partnerships are not guaranteed to be fairer or more representative. But they do demonstrate the appetite of emerging economies and recipient countries for other types of co-operation outside the traditional North-to-South paradigm.

These new alternative partnerships are not guaranteed to be fairer or more representative. But they do demonstrate the appetite of emerging economies and recipient countries for other types of co‑operation outside the traditional North-to-South paradigm.

Although competition between actors poses certain risks to development co-operation, such as the duplication of efforts, it is also an accelerator for developing countries to acquire more agency and leverage. The presence of more development actors means more choices for countries that previously may have been compelled to rely on any and all aid available to them. Bilateral and multilateral partners may find themselves forced to innovate their practices and strategies, thus jumpstarting necessary reforms to the development sector overall, and recipient countries, with more options and bargaining power, may be able to better align co-operation to their individual interests and goals (Silva, Bernardo and Mah, 2021[27]). Whether or not recipient countries can take advantage of more leverage is an implementation challenge and dependent on several factors, including the domestic political economy. But the current context is opening the opportunity for new alternatives and power dynamics.

Recent steps taken by development actors also show that there is the global political will for change in the development sector. For example, individual countries, including China, the Russian Federation and the United States, have demonstrated – through visits, strategies and summits – their interest in redefining and strengthening partnerships with countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia. Such announcements and summits signal global players’ political will, accelerated by competition, to redefine partnerships and development co-operation. Recipient countries are also showing political will, as demonstrated by Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who recently called for a new global financial architecture and offered specific recommendations (Box 2.1). She stresses that the current system is unfair to developing nations and suggests that it be reformed to include the voice and recognise the agency of developing nations, especially in Africa and the Caribbean (Government of Barbados, 2022[34]). Finally, there is also political will among multilaterals. For example, the UN Secretary-General recently released recommendations for the future of multilateralism, stating that reforms to multilateralism and global governance are desperately needed (UN, 2021[35]).

Box 2.1. Prime Minister Mottley’s recommendations for reforming the international financial system

1. Reform the UN Security Council, especially its panel of permanent members, which currently lacks representation for more than 1.5 billion people of African descent.

2. Democratise the system of global governance, particularly the Group of Seven and Group of Twenty (G20), by broadening representation to include the African Union as a full member.

3. Reallocate unused special drawing rights issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to assuage liquidity constraints in the Global South.

4. Develop new facilities for food and agriculture, clean energy, and climate change adaptation in response to emerging global challenges.

5. Cap debt service payments to a certain percentage of exports.

6. Reform global credit rating agencies to correct their intrinsic biases that have led global investors to overprice risks in the Global South.

7. Suspend temporary surcharges by the IMF, which further raise the debt burden at a time when rising interest rates are exacerbating the fiscal incidence of sovereign debt.

8. Take advantage of the IMF’s General Review of Quotas to reform Bretton Woods institutions and account for shifting economic weights.

9. Increase long-term financing and longer maturity loans to support economic development and structural transformation in low-income countries.

10. Reform the Bretton Woods institutions and hold them accountable to fulfil their mandate.

Source: Mottley (2022[36]). The Developing World in a Turbulent Global Financial Architecture: The 6th Annual Babacar Ndiaye Lecture, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLT1YMJ0jM4.

The policies: Do not overlook the power of domestic political economy

The third and final stream involves the emergence of policy proposals, often from specialists, that can constitute potential solutions to the problem. While consensus can be difficult to achieve, especially when there are competing development priorities, it has been done: Witness the creation of the Millennium Development Goals and the SDGs. Similarly, development actors are now in general agreement that the development sector should prioritise localisation (Robillard, Atim and Maxwell, 2021[37]) and open and inclusive partnerships (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2022[38]). From the perspective of developing countries, the effects of polarisation have been both positive and negative. For example, China’s presence and power in Africa have helped expand connectivity and infrastructure during a time when US engagement with Africa was low (Ramani, 2021[39]). Yet despite advances, many African countries have taken mounting debt owed to China, which ultimately impedes sovereignty in the long term. Throughout these geopolitical changes, recipient countries have been able to agree on general policy frameworks regarding what the relationship between donors and recipients should look like in the future. According to recent surveys, there is consensus among developing country leaders around the idea that international development actors have a supporting role to play in all areas of development policy but that donors should prioritise flexibility, responsiveness and commitment to tailor aid and other contributions to local needs and domestic goals when considering the future of development co-operation (Wooley, 2022[40]).

Leveraging knowledge and theories about why policies succeed or fail presents an additional opportunity to reset international development. This can help donors and recipients better understand their own political economy and how it might interact with a partner’s. Discussions of political economy and development typically centre around the global political economy and overlook the power of the domestic political economy. But pivoting to focus on the domestic political economy makes it possible to home in on implementation outcomes since development actors, public and private, all operate within their own political economies. The implementation theory developed by Matland (1995[4]) uses an ambiguity-conflict political economy model to explain why the implementation of a given policy succeeds or fails (Box 2.2). Policy implementation theories such as Matland’s should be used not only nationally but also locally so that institutions and recipient countries can identify potential points of resistance and better understand the structural features and power distributions across social groups that will influence implementation outcomes (Hout, 2015[41]).

Box 2.2. Why some policies succeed when others fail

Policy conflict arises when individual self-interested actors come into conflict because their interests diverge; policy ambiguity is when a policy’s goals, strategies or means are unclear. Examining various unique implementation scenarios through the lens of these two factors and in conjunction with other relevant factors beyond the political economy – the Fourth Industrial Revolution, agile governance, the global private sector, and the full inclusion of youth and women – can be a powerful way of conceptualising and overcoming the implementation gap that often plagues the development sector.

For example, when both conflict and ambiguity are low, policy implementation is administrative, and success depends on the availability of resources and institutional capacity. Rwanda is one example of a country that has engaged in long-term planning based on its own demographic, economic and political landscape (low ambiguity) and has relatively low conflict due to consensus over policy goals and high stability (Musiitwa, 2012[42]). Within this context, successful implementation in Rwanda will rely on financial and technical resources. The development community can therefore focus on increasing foreign direct investment and other resources to implement its agenda.

When conflict is high and ambiguity is low, implementation is political, and success depends on power. South Sudan is an example of a country that had a clear policy strategy for development out of fragility when it was created (low ambiguity) but high conflict between political parties (high conflict). This situation creates the need to resolve political conflict through inclusive and accountable political participation, which can then be the focus of development actors.

When conflict is low and ambiguity is high, implementation is experimental, and success depends on contextual conditions. Poverty eradication policies typically fall into this category. African countries generally find themselves in this situation, where most actors depend on pursuing a development goal (low conflict) but the policy or way forward for addressing these complex issues is difficult or unclear (high ambiguity). This is common when there are competing domestic priorities or grievances. In this example, development actors can play a positive role by sharing research and information and prioritising strategy development to reduce ambiguity (Signé, 2022[43]).

Finally, when conflict and ambiguity are both high, policy implementation is symbolic, and implementation depends on the strength of the coalition. This context is common for highly fragile contexts since conflict and violence may be high and coupled with high ambiguity due to state illegitimacy, lack of formal enterprise and vulnerability to shocks. In such cases, development actors should prioritise reinforcing, stabilising and strengthening authority in line with a long-term national security strategy (Signé, 2019[24]).

Note: Examples and illustrations provided by the author.

Sources: Matland (1995[4]), “Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation”, 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242; Musiitwa (2012[42]), “New game changers in Africa's development strategy”, 10.1057/dev.2012.84; “US Secretary of State Blinken to visit Africa as tension with China and Russia intensifies”, Signé (2022[43]), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2022/08/05/us-secretary-of-state-blinken-to-visit-africa-as-tension-with-china-and-russia-intensifies/; Signé (2019[24]) “Leaving no fragile state and no one behind in a prosperous world: A new approach”, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/LNOB_Chapter11.pdf.

Towards a new agenda for international development

While polarisation is putting the convergence of policies at risk, development actors can focus on a few key policies that can have a significant impact. Within the development community, the three streams identified by Kingdon (1984[3]) as key to new agenda setting appear to be converging, opening a window of opportunity to implement changes in the development sector even when polarisation and complexity are high, including a paradigm shift both within and between development actors. Recipient countries are now seeing the effects, both positive and negative, of the new geopolitical order and are converging on the policies for a way forward – one that focuses on co-operation principles for a more level playing field such as adaptability, sustainability, inclusivity and reciprocity; the recognition of China as an influential player; and the understanding that while multilateralism is an effective venue for collective action, its flaws must be acknowledged (Custer et al., 2021[44]).

Each development actor has its own unique set of incentives, structures, strengths and tools, and each faces its own uncertain future as development co-operation changes in response to ongoing global shocks and trends. This section presents three main categories of recommendations for development actors to redefine development and successfully implement a new agenda that addresses the global political economy, the domestic political economy, and the transversal challenges and opportunities unique to the current context. The categories were chosen because they comprise issues for which a window of opportunity is opening within the development sector for new approaches that could be adopted and implemented successfully.

Address the global political economy challenge

To ensure convergence of the problem, politics and policies, major development players need to be relatively aligned on a new paradigm of development co-operation that puts recipient countries in the driver’s seat for development through partnerships that are both local and agile. Current and future complexity requires agile leadership, agile systems and agile development strategies. This means reorienting systems and thought processes away from previous views of development (as static, linear, independent and directly measurable) towards an agile understanding of development as dynamic, non‑linear, adaptive and uncertain. Practically speaking, this means shaping development as it unfolds and responding to emerging dynamics rather than proceeding according to a predefined, unchanging plan (Silva, Bernardo and Mah, 2021[27]).

Improve co-operation among donors to prevent duplication of efforts

In addition to agility and alignment, co-operation between development actors is necessary to prevent duplication of efforts. When competition between donors is high, as it is now amid geopolitical tension, partnership and communication among competitors are low, leading to the risk of duplication of efforts or, even worse, one actor’s actions unintentionally undermining the goals of another.

Co-ordination efforts among countries should consider each country’s comparative advantage when it comes to how development efforts are structured (Ingram, 2020[33]). The extent and level of collaboration between donors depend on commonalities of development objectives, the level of engagement within the region of a country or sector, and the level of alignment among donors on foreign policies (Ingram, 2020[33]). Bilateral co-operation will have to consider the level of integration possible given the political will and environment of the donor countries. Typically, the more integration there is, the higher the impact; however, more integration with closer collaboration such as shared governance or pooled resources requires significant political will. Loose co-ordination such as dialogues may have less impact but may be more suitable when political will is low (Ingram, 2020[33]).

While bilateral co-operation will continue, multilateral channels may be more effective for collaboration on strategies and financing. Donors themselves should also focus on outreach strategies and communication to identify their projects and priorities to avoid overlap and redirect resources towards other needs (Hronešová, 2018[45]). If the competitive environment persists, countries could be incentivised to avoid duplication by framing this as a way to develop competitive advantages or use their existing competitive advantages more efficiently. Collaboration should be promoted as a way for donor countries to benefit from their technical and non-financial assistance and networks (Harbour et al., 2021[46]). Emphasising that collaboration is, in fact, in each individual country’s national interests can be a way to push back against polarisation.

Reinforce the value and legitimacy of multilateralism

Development actors, where possible, should reemphasise the importance and legitimacy of multilateralism as the premier venue for better co-ordination. The first step is for multilateral institutions to reform themselves to actually give developing countries equal representation in decision-making bodies. A fairer system for developing nations to make their voice heard in dialogues and in votes would help build these countries’ trust in multilaterals.

Multilateral institutions should take steps to make financing more equitable as well, starting with decreasing the level of bilateral funds that are earmarked for specific purposes and recommitting to a broad and democratic approach to establishing priorities and allocating funds. The increase in bilateral aid under the umbrella of multilateralism delegitimises the need for multilateral institutions in the eyes of the rest of the development world and the public. Multilateralism is desperately needed given today’s increasingly complex issues – but only if multilateral institutions act to be more fairly representative and leverage the strengths of their own unique structures.

The increase in bilateral aid under the umbrella of multilateralism delegitimises the need for multilateral institutions in the eyes of the rest of the development world and the public.

Multilateral development financing can also be enhanced through technical reforms. Various technical recommendations have been made to increase the scale of multilateral development bank (MDB) activities. Kharas (2021[14]) has suggested that “while maintaining a AAA rating, MDBs could expand their loan books by at least (USD) 750 billion simply by using better accounting practices on how callable capital is measured. They could move towards industry standards on risk management variables like the equity‑loans ratio”. They further could mobilise more private capital and local counterpart funds in partnership with national banks and sell selected loan assets if these were properly priced at the outset. It would also be possible for MDBs to ask shareholders to provide them with additional equity, though this would be a last resort.

Greening international development co-operation

Enhancing bilateral and multilateral co-operation in a more just way is even more critical when it comes to climate change, given that there is a mismatch between advanced economies, which are contributing more to the problem, and low- and middle-income countries, which are disproportionally feeling its effects. Efforts to green development co-operation should be strengthened by approaching sustainability systematically at all stages of a policy or plan, including throughout implementation (OECD, 2020[47]). Projects and programmes are already assessed for environmental impacts before the project – especially those from intergovernmental organisations or multilateral institutions. But to avoid the risk of contradictory choices or trade-offs from leadership, sustainability needs to be mainstreamed within development strategies and programmes. For example, while environmental goals are prioritised within the Aid for Trade (A4T) initiative, they are not mainstreamed. Between 2010 and 2020, more than USD 200 billion in climate‑related aid for trade commitments were made (OECD/WTO, 2022[48]), but A4T lacks an overall mainstreamed framework for environmental considerations and leaves systematic environmental considerations up to individual donors (Birkbeck, 2022[49]). Individual donor countries often have their own environmental guidelines for A4T projects, a practice that may need to be revisited.

Partnerships like the one between China and the Asian Development Bank, which co-create high‑quality green development plans, should be replicated and strengthened. These partnerships should emphasise the need for private sector co-operation, especially for green infrastructure and such projects as wastewater treatment and off-grid clean energy (ADB, 2021[50]). China and the EU have led efforts to reform global green finance by creating a “set of fundamental standards for selecting appropriate investment targets for green bonds” (Jia, 2021[51]). Their classification process is now being replicated in other countries, including Colombia, Mongolia, Singapore and South Africa. These efforts in collaboration with the private sector should be strengthened and supported by development actors, as a unified taxonomy is necessary to enable developing and emerging countries to issue more green bonds. Polarisation is putting action on this priority at risk, as significant co-operation among major players is needed.

Efforts in collaboration with the private sector should be strengthened and supported by development actors, as a unified taxonomy is necessary to enable developing and emerging countries to issue more green bonds.

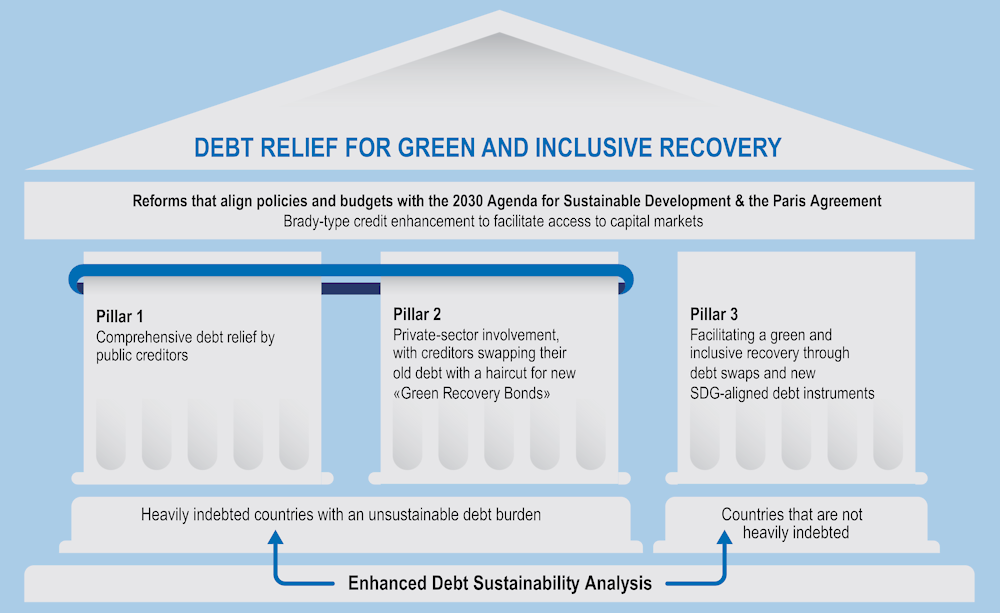

Greening international co-operation will also have to include tackling the debt crisis in developing countries, given that most of the top 50 most climate-vulnerable nations are also among the countries with the most severe debt problems (Jensen, 2022[52]). There is a general consensus that the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments must be reformed to add additional liquidity support to deliver more effective and resilient debt relief and involve private creditors that hold a large chunk of the debt (Jensen, 2022[52]). However, the Common Framework reform will not be enough to address the systemic issue. A 2020 report for Project Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery argued that public and private creditors should be required to provide debt relief for low- and middle-income countries in exchange for a commitment to a green recovery (Volz et al., 2020[53]) (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Debt relief for low- and middle-income countries can underpin a green and inclusive recovery

Source: Volz et al. (2020[54]). Proposal: Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery: Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery. https://drgr.org/our-proposal/proposal-debt-relief-for-a-green-and-inclusive-recovery/.

Debt forgiveness is not the only way to increase fiscal space. A country could seek to increase its debt limit by boosting market confidence, whether through bilateral currency swap lines, access to finance with regional and global institutions with low conditionality, swapping foreign currency debt for local currency debt, or other means. Some countries will have more access than others to more of these options and some will have no choice but to seek out traditional debt forgiveness programmes. While it is critical to link debt recovery and sustainability goals, it may have to come through the actions of the creditors. The international community can and should work to improve the borrowing conditions for developing countries by strengthening information ecosystems and extending the horizon of credit ratings (Spiegel and Schwank, 2022[15]). A systematic change to the debt relief and restructuring initiatives will be needed but should include voices from developing countries to ensure that well-intentioned programmes are taken up by the leadership.

In the context of growing power rivalries and polarisation, developing countries should strengthen regional development and security co-operation

With increased polarisation putting development and sustainability at risk, developing countries should elevate their security agenda from a national to a continental or regional level. Outsourcing domestic security has failed to deliver stability and has undermined development and regional integration efforts. Instead, countries should adopt a continental and/or regional approach, which will have positive security effects and, eventually, economic effects by strengthening the implementation of regional trade agreements such as the African Continental Free Trade Area. Regional bodies have specific strengths in terms of safeguarding public goods, and regionalism can help countries overcome their deep-rooted conflicts, consolidating peace and human rights. By strengthening these bodies, developing regions can increase their international negotiating power, lower the cost of national security promotion for individual countries, and ensure long-lasting peace and security. Strengthening regional co-operation can be an effective way for developing countries to reduce the risks that polarisation brings and ensure that development paths are not dependent on the political or economic will of a single partner. A regional approach, as outlined in the African Development Bank’s fragility strategy in 2015, can also build resilience against spillover effects of conflicts in one country on other nearby countries (Signé, 2019[24]).

Whether or not they interact directly with regional actors, all development actors should recognise the importance of regional actors as connectors between bilateral or multilateral actors and local implementation (Signé, 2018[30]). For example, subnational development banks are great connectors between bilateral or multilateral actors’ resources and implementation in local communities since they are much closer to the local context and hold institutional knowledge about needs and projects (Suchodolski, De Oliveira Bechelaine and Modesto Junior, 2020[55]). Subnational development banks can therefore contribute to regional development by choosing a more representative pool of projects than a national bank would be able to do. Governments and investors can help subnational banks by supporting initiatives that promote risk mitigation and accelerate digital transformation, especially within the financial sector.

Address domestic political economy challenges

Development actors should also recognise the importance of the domestic political economy, particularly as it relates to implementation.

Base development strategies on local strengths and structural transformation rather than focusing on deficiencies

To successfully implement development strategies, policy makers “should hone, not neglect, small and often-overlooked innovations, since they frequently contribute to economic paradigm change in the long run – even when success is not apparent in the short run” (Signé, 2017[56]). Yet, as noted by Monga (2019[57]), development economists and institutions have been overly focused on deficiencies or gaps in developing countries, leading to the notion that economic or development progress is contingent on an exhaustive list of preconditions related to infrastructure, human capital, financing or any number of other factors. Strategies should instead be focused on the strengths of each individual country and how these can be leveraged for structural transformation. In doing so, development actors can provide actionable recommendations that are rooted in a country’s situation and politics rather than a laundry list of recommendations that may not be politically or financially viable and that are treated as prerequisites for development progress.

The private sector can play a role in this area as it typically excels at identifying sectors with a comparative advantage. These can then become priorities for governments and their development partners, which can tailor their efforts to the infrastructure, human capital, reforms and other areas needed for those sectors to flourish (Monga, 2019[57]). With competing priorities, “not all innovations are created equal. Policy makers should identify and adopt the critical innovations that enhance the rules of the game and produce long‑term policy and economic transformation” (Signé, 2017[56]).

Developing countries themselves should engage stakeholders to develop a long-term vision within an institutional framework and leverage endogenous innovation to achieve long-term economic transformation

States must bring their own leadership and political will to the table to implement development plans and strategies. Regardless of any genuine progress in development strategies from outside actors, if the developing state itself is not equipped with the resources, capabilities, leadership and openness to change that are needed to implement various strategies, development efforts will fall short. The evidence is clear that accountable leadership (personal, peer, vertical, horizontal and diagonal) is key to successful economic transformation in Africa, given that outperforming economies overall are associated with higher levels of accountability (Signé, 2018[58]). Studies of economic growth in Africa over a 40-year period, edited by Ndulu et al. (2007[25]), reached similar conclusions: Syndrome-free African economies and outperformance were mostly associated with the nature of political regimes (especially democratic) in the decades after 1990, with syndromes such as regulatory regimes, ethno-regional distribution, intertemporal distribution and state breakdown negatively affecting economic growth in Africa.

Recipient countries should engage various stakeholders to develop priorities and a plan that extend beyond a single leader or political cycle to reduce policy ambiguity (see Chapter 20). Regional bodies or civil society may act as effective conveners for this purpose. Often, the incentive for government leaders to sacrifice long‑term goals for short-term rewards acts as a barrier to successful implementation. If strategies are embedded in government ministries and institutions independent of politics, this will minimise the risk of progress getting lost between political cycles.

The private sector can and should play a key role here, especially when it comes to working with the state to promote stability, which is of mutual interest to the public and private sectors. Governments should take the necessary steps to strengthen institutions and increase transparency to incentivise private sector investment. In situations where the resources or political will do not exist and institutions remain weak, states could benefit from regulatory partnerships in which the international community mandates and oversees regulations. To avoid overreach (i.e. outside partners meddling with domestic policy decision making), these partnerships should be based on aligning regulations to domestic legislation and context while using international partners for governance and monitoring (Signé, 2019[24]).

Leverage the strengths of ODA in crisis situations and fragile contexts, using it to steer other resources, and increase transparency and accountability of ODA flows for the public and recipients

While ODA in development finance has not grown as much as it had in private finance as of 2019, it remains a powerful development tool that should not be overlooked. ODA is well placed and well suited to act as a reliever for global shocks, particularly humanitarian concerns and health crises such as the current pandemic. It can also point other types of financing in the right direction and align them to long-term strategies (OECD, 2019[59]).

ODA is critical not only for relieving the consequences of global shocks, but also for fragile contexts. Solutions are difficult to achieve as many of the drivers of fragility are cyclical, trapping fragile contexts in a cycle exacerbated by inconsistent and ineffective aid and FDI. To address these challenges, development actors should shape strategies for fragile contexts using the ambiguity-conflict framework. This means taking into account the overall political economy of policy implementation and country-specific contexts (i.e. policy ambiguity, conflict, decentralisation and private sector support) (Signé, 2019[24]). Some development actors are developing new fragility strategies that include reconsidering levels, types and recipients of aid based on the domestic political economy. Going forward, aid should prioritise humanitarian assistance in extremely fragile states, but in fragile states with prominent civil society and private sectors, aid should focus on developing and rebuilding commercial and economic sectors within the country (Signé, 2019[24]).

Address transversal challenges

The development community should also seize opportunities presented by several transversal trends as it seeks to redefine and successfully implement a new agenda, including by capitalising on the role of emerging technologies and the 4IR and on the potential of women, youth and the private sector.

Leverage the role of emerging technologies and the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Development actors should prepare for, embrace and leverage the 4IR and its technologies to transform development. The 4IR, contributing to and growing from digital transformation, has great potential to allow countries to bridge gaps in governance, commercial and social progress (Signé, forthcoming[60]; 2019[24]). Frontier technologies can help accelerate green development in developing countries, where technological leapfrogging is possible (UNCTAD, 2022[61]). By helping to reach vulnerable populations such as youth, women, marginalised groups and rural communities, digital transformation can more effectively deliver services, disseminate information and connect these groups to the formal economy. If the goals of the All Africa Digital Economy Moonshot are met, for example, Africa will increase its per capita growth by 1.5 percentage points and reduce poverty by 0.7 percentage points (Calderon et al., 2019[62]). This growth could be even greater if coupled with human capital gains. These goals cannot be achieved, however, without the intentional inclusion of marginalised groups in the benefits of digitisation, and this will require focusing on developing technologies, infrastructure and digital skills for marginalised groups (Qureshi, 2022[63]). Connecting the informal sector to the formal economy can be accelerated through financial inclusion, which is already on the rise thanks to digital banking in African countries. Financial inclusion can lead to greater capital accumulation and investment, which can lead to formal employment growth (Ndung’u and Signé, 2020[64]).

Countries and development partners should develop and update holistic strategies for technology in development using a systems approach to assess the risks and opportunities of digitisation and emerging technologies. These strategies should emphasise updating governance structures to allow for an endogenous innovative environment as well as regulations that encourage competition and protect consumers and the market (Ndung’u and Signé, 2020[64]). Agile governance and enabling environments are critical and should be prioritised within a country’s digital strategy.

The opportunities presented by advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain and biometrics are tremendous. But they require investment in physical and digital infrastructure and digital skills to reach their potential in developing countries. Development actors should orient their strategies, financing and partnerships around these priorities. The effects of the 4IR are felt by all, which means the 4IR is an area where collaboration could overcome polarisation if interests are aligned. However, polarisation and geopolitical tensions are increasing the risk of inequality and dominance in the emerging technology sectors, which could create new power structures. To reduce this risk, the 4IR should be a central topic within multilaterals and other development co-ordination bodies. Multilateral bodies in particular can play an important role in ensuring that the norms and standards governing digital space are inclusive of all countries’ realities (OECD, 2021[65]).

In 2021, the UN Industrial Development Organization launched the first “development dialogue” on its Strategic Framework for the Fourth Industrial Revolution to share with regional groups its strategy for harnessing the 4IR for development, which focuses on “the development of innovation ecosystems, skills and capacity-building, governance, partnerships, investment and infrastructure” (UN, 2022[66]). Other groups have facilitated similar conversations, including Frontier 2030 of the World Economic Forum and the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation (World Economic Forum, 2020[67]). Intergovernmental groups should continue to convene countries and other development actors to address the 4IR and related issues such as cybersecurity.

Give gender and youth the place they deserve in development

Another transversal issue that should be prioritised as part of a redefined development sector is the full inclusion of women and youth in terms of outcomes and decision-making bodies. While frameworks, strategies and high-level discussions often refer to women and youth as central development actors, actual action to make them true partners has been limited. Not only is there a moral obligation to not leave these populations behind in discussions or in projects – there is a compelling economic case as well. Advancing gender equity in employment is estimated to increase GDP by an average of 35% (Lagarde and Ostry, 2018[68]), and yet women are blocked from formal employment both by specific laws and restrictions in some countries and by societal expectations that can lead to them bearing a double responsibility with child care and work (UN Women, 2018[69]). Equal access to education, financial services, the Internet and mobile phones will be critical to overcoming these barriers.

Development actors should also work towards greater inclusion and representation of gender and youth within institutions, local projects and programmes. Various studies have shown that outcomes are better when women are included in political decision-making processes. For example, in India, communities with female-led councils had 62% more drinking water projects than communities with male-led councils (UN Women, 2022[70]). Youth participation in political spaces is also disproportionately low, and extremely so. People under the age of 30 make up more than 50% of the world’s population, yet only 2% of the members of parliament worldwide (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2021[71]). Young people are also underrepresented in international organisations, although the UN began to encourage youth delegations in 1981; as of 2019, only 40 of the 173 UN members had created youth delegations (Kuhn, 2020[72]). Countries should deliver on this commitment and elevate the status of youth delegations not only to the UN but also to other co-ordination bodies that discuss policy priorities and implementation.

Capitalise on the global private sector

A look at the data on aid flows makes it clear that the public sector alone cannot achieve development goals. There is no option but to turn to private sector funds. The global private sector has many advantages that should be capitalised on, including its ability to act and mobilise resources quickly. Public development actors can and should do more to support private sector financing for development. Only USD 1 billion of the USD 178.9 billion in total ODA flows from DAC members in 2021 was dedicated to development-oriented private sector instrument vehicles (OECD, 2022[73]). This is a huge missed opportunity for public‑private sector collaboration in the long term, and donor countries should consider investing more in this area.

FDI should be reemphasised as an important vehicle for development finance as it can create new markets, accelerate regional value chains, and generate domestic jobs and revenue. While total FDI levels overall have recovered somewhat since their low point in 2020, growth has been more modest in least developed countries than in other countries (UNCTAD, 2021[74]). However, there is a growing understanding that FDI and multinational companies can have profound effects on recipient countries, even those that are considered fragile: “FDI in local industries has the unique advantage, compared to nation- or donor-led stabilization policies, of removing the economic conditions that contribute to groups’ grievances, poverty, hunger, and political rivalry – creating short-term and long-term avenues for exiting stages of fragility” (Signé, 2019[24]). These effects are difficult to achieve, however; first, given the mismatch in co-ordination and domestic accountability for FDI and second, in light of past failures where FDI in extractive resource industries increased fragility, as was the case in central Africa and with mining operations in the Dominican Republic (Signé, 2019[24]).

Development actors can help drive FDI towards positive impacts by working directly with partner countries to develop regulatory reforms or working directly with businesses and investors to incentivise investment in specific sectors, for example, supporting green transitions, and to influence behaviour. As noted by the OECD (2022[75]), these two approaches are rarely presented together in a comprehensive strategy specific to a country’s context, which leads to either duplication or misaligned assistance. Addressing co-ordination and information gaps is key for maximising FDI impact. Development actors can help investors better engage with new trade agreements, such as the African Free Continental Trade Agreement.

Private finance for development projects has certain advantages, in particular the scale and speed at which it can be deployed. Nonetheless, some precautions should be taken given that private sector players, unlike other development actors, are likely to operate under incentives and accountability structures that do not include green or inclusive development as a central goal. The development community can play a role in developing, tailoring and strengthening incentives specifically for the private sector to work towards mutual goals. Development actors should support the economic agenda of the private sector and leverage these incentives through potential solutions, including helping to modernise inclusive business tax reform, to initiate research and development investment, and to streamline credit rating systems for developing economies (Khasru and Siracusa, 2020[76]). Wherever possible, the development community should work to find areas of common interest even under different incentives and work from there to find solutions for developing greater alignment.

Private sector players, unlike other development actors, are likely to operate under incentives and accountability structures that do not include green or inclusive development as a central goal.

In addition, multilateral development actors can work to encourage a greater role for women in leadership for private sector investment in emerging markets. In 2019, 68% of investment teams in emerging markets were all male (Payton, 2022[77]) and only 7% of venture capital funding went to women-led businesses (Government of Canada, 2021[78]). It is clear that private sector financing will be necessary to reach development goals, but public and private actors should work together to co-ordinate efforts and embed inclusivity – which could start with a greater emphasis from multilaterals.

The international community should also encourage greater collaboration around development with philanthropic donors. Philanthropic giving has soared in the past few years; individuals and foundations now have a significant say in development plans, priorities and projects. As of 2018, philanthropic flows accounted for 8% of all development financial flows to low- and middle-income countries (Silva, Bernardo and Mah, 2021[27]). While increased financial inflow is positive, philanthropic financing for development can easily become problematic or create further power imbalances as these efforts may not necessarily be co-ordinated with the goals of other actors or include the same type of oversight or accountability. The development community could contribute by providing a platform that encourages greater transparency and dialogue between country leaders on the one hand and local and global philanthropic actors on the other (Ilasco, 2022[79]). An example is the philanthropy and development strategy developed by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (2021[80]), which has been a successful convener to connect local foundations in France and in developing countries to find areas of mutual commitment.

At the same time, the development community should push global businesses to continue to reframe systems away from shareholder capitalism and towards a stakeholder capitalism that no longer prioritises short-term profit maximisation but considers broader societal goals connected to the health and wellness of people and the planet (Schwab and Vanham, 2021[81]). Recipient countries need to continue to work towards creating an enabling environment that respects their domestic goals but appeals to international business concerns. This includes increasing the transparency and accountability of domestic institutions, a process that digital systems could accelerate.

Conclusion

With the rapid development of emerging technologies, the global spread of diseases, increasingly integrated financial systems and the consequences of climate change, the world is facing and will continue to face no shortage of global challenges. At the same time, countries are turning inward and major development and economic players including China and the United States are becoming even more polarised. These geopolitical tensions are shifting the dynamics within the development sector. More emerging economies are becoming development actors, generating more competition for partnerships, more options and thus more leverage. With development goals yet to be met in many parts of the world, the fact remains that development co-operation is essential. Given that the need for change is generally acknowledged, that developing countries have increasing leverage, and that there is general agreement on prioritising locally led development, the three streams – problem, politics and policies – are converging. This means that a unique window of opportunity is opening to shift the traditional paradigm of development aid and co-operation.

Beyond a paradigm shift, successful implementation, often the major barrier to achieving development outcomes, will be key. New strategies and co-operation must consider the domestic political economies of both the donor and recipient and tailor implementation strategies to them. While the current level of polarisation poses a great risk of misalignment of donor and recipient countries’ priorities, some areas and recommendations should take precedence during this window of opportunity. Among these are recommendations that address the global political economy, the domestic political economy and transversal challenges. Development co-operation cannot be successful if it tries to apply old methods to the new and increasingly complex challenges of today. Instead, it must be based on strategic co-ordination that leverages the strengths of each player and with developing countries in the driver’s seat.

References

[50] ADB (2021), Greening Development in the People’s Republic of China: A Dynamic Partnership with the Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Manila, https://doi.org/10.22617/TCS210335-2.

[12] Aris, B. (2022), “Russia preparing for second Africa Summit to build closer ties as it pivots away from the West”, BNE IntelliNews, https://www.intellinews.com/russia-preparing-for-second-africa-summit-to-build-closer-ties-as-it-pivots-away-from-the-west-247188 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[22] Berhane, S. (2021), “What does the downgrading of Ethiopia’s credit rating entail?”, The Reporter, https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/10932 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[49] Birkbeck, C. (2022), Greening Aid for Trade and Sustainable Development: Financing a Just and Fair Transition to Sustainable Trade, International Institute for Sustainable Development, Winnipeg, Manitoba, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2022-07/greening-aid-trade-financing-just-transition.pdf.

[2] Bradford, C. (2022), “Commentary: The US and China: Making room for global cooperation”, Institute for International Political Studies, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/us-and-china-making-room-global-cooperation-36685 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[62] Calderon, C. et al. (2019), “An analysis of issues shaping Africa’s economic future”, Africa’s Pulse, Vol. 19, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1421-1.

[13] Chadwick, V. (2022), “Internal report shows EU fears losing Africa over Ukraine”, Devex, https://www.devex.com/news/exclusive-internal-report-shows-eu-fears-losing-africa-over-ukraine-103694#xd_co_f=NGZkNjI5MjEtMjgzNy00MThkLWJmMjktNDI5ZTA4ZWFiZWUz~ (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[44] Custer, S. et al. (2021), Listening to Leaders 2021: A Report Card for Development Partners in an Era of Contested Cooperation, AidData at the College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[10] Fofack, H. (2022), Dawn of a Second Cold War and the “Scramble for Africa”: Adopting a United Approach to Security Promotion is Crucial if Continent is to Achieve its Economic Aims, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/research/dawn-of-a-second-cold-war-and-the-scramble-for-africa (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[80] French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (2021), Philanthropy and Development: Stocktake and Partnership Strategy, French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, Paris, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_drm_philanthropy_eng_web_cle0ab7b4.pdf.

[7] Ghosh, I. (2020), “How China overtook the U.S. as the world’s major trading partner”, Visual Capitalist, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/china-u-s-worlds-trading-partner (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[19] Gill, I. (2022), “Developing economies face a rough ride as global interest rates rise”, Brookings Future Development blog, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/02/28/developing-economies-face-a-rough-ride-as-global-interest-rates-rise (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[34] Government of Barbados (2022), The 2022 Barbados Agenda, Government of Barbados, https://gisbarbados.gov.bb/download/the-2022-barbados-agenda (accessed on 4 November 2022).

[78] Government of Canada (2021), Private Sector Engagement for Sustainable Development, Government of Canada, https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/priorities-priorites/fiap_private_sector-paif_secteur_prive.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[18] Ha, J., A. Kose and F. Ohnsorge (2022), “Coping with high inflation and borrowing costs in emerging market and developing economies”, Brookings Future Development blog, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2022/05/05/coping-with-high-inflation-and-borrowing-costs-in-emerging-market-and-developing-economies (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[46] Harbour, C. et al. (2021), “How donors can collaborate to improve reach, quality, and impact in social and behavior change for health”, Global Health: Science and Practice, Vol. 9/2, pp. 246-253, https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00007.

[41] Hout, W. (2015), “Putting political economy to use in aid policies”, in A Governance Practitioner’s Notebook: Alternative Ideas and Approaches, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/accountable-effective-institutions/Governance%20Notebook%201.4%20Hout.pdf.

[45] Hronešová, J. (2018), “Donor coordination still lagging behind”, EU-CIVCAP, Brussels, https://eu-civcap.net/2018/10/01/donor-coordination-still-lagging-behind (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[79] Ilasco, I. (2022), “Private philanthropy in international development, between praise and criticism”, DevelopmentAid, https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/135778/private-philanthropy-in-international-development (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[33] Ingram, G. (2020), Development in Southeast Asia: Opportunities for Donor Collaboration, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Development-Southeast-Asia-Ch1-Policy.pdf.

[71] Inter-Parliamentary Union (2021), “Parliaments are getting (slightly) younger according to latest IPU data”, https://www.ipu.org/youth2021-PR (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[52] Jensen, L. (2022), “Avoiding ‘too little too late’ on international debt relief”, Development Futures Series Working Papers, United Nations Development Programme, New York, NY, https://www.undp.org/publications/dfs-avoiding-too-little-too-late-international-debt-relief (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[51] Jia, C. (2021), “China, EU lead ’green revolution’ with finance standards”, China Daily, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202104/29/WS608a0eeca31024ad0babb2c0.html (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[1] Jones, B. (2020), “How US-China tensions could hamper development efforts”, Brookings Order from Chaos blog, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/09/17/how-us-china-tensions-could-hamper-development-efforts (accessed on 28 November 2022).

[14] Kharas, H. (2021), “Global development cooperation in a COVID-19 world”, Global Working Paper, No. 150, Center for Sustainable Development, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Global-Development-Cooperation-COVID-19-World.pdf.

[76] Khasru, S. and J. Siracusa (2020), Incentivizing the Private Sector to Support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Global Solutions Initiative, Berlin, https://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/incentivizing-the-private-sector-to-support-the-united-nations-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 29 November 2022).

[3] Kingdon, J. (1984), Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, Little, Brown & Co., Boston.

[31] Klingebiel, S. (2021), “What future for the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee?”, The Current Column, German Institute of Development and Sustainability, https://www.idos-research.de/en/the-current-column/article/what-future-for-the-oecds-development-assistance-committee (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[72] Kuhn, A. (2020), “Do youth delegates at the UN have an influence on public international law?”, Völkerrechtsblog, https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/do-youth-delegates-at-the-un-have-an-influence-on-public-inter (accessed on 4 November 2022).

[68] Lagarde, C. and J. Ostry (2018), “Economic gains from gender inclusion: Even greater than you thought”, IMF Blog, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2018/11/28/blog-economic-gains-from-gender-inclusion-even-greater-than-you-thought (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[4] Matland, R. (1995), “Synthesizing the implementation literature: The ambiguity-conflict model of policy implementation”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. 5/2, pp. 145-174, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a037242.

[23] Mbaye, A. and Signé (2022), “Climate change, development, and conflict-fragility nexus in the Sahel”, Brookings Global Working Paper, No. 169, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/research/climate-change-development-and-conflict-fragility-nexus-in-the-sahel (accessed on 4 November 2022).

[32] McCaffrey, C. et al. (2021), 2022 Geostrategic Outlook: How to Thrive in a Turbulent 2022, Ernst & Young LLP, New York, NY, https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/geostrategy/ey-2022-geostrategic-outlook.pdf.

[5] Mélonio, T., J. Naudet and R. Rioux (2022), “Official development assistance at the age of consequences”, Policy Paper No. 11, Éditions AFD, Paris, https://www.afd.fr/en/official-development-assistance-age-of-consequences-melonio-naudet-rioux.

[38] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (2022), Joint Statement of the Coordinators’ Meeting on the Implementation of the Follow-up Actions of the Eighth Ministerial Conference of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202208/t20220819_10745593.html (accessed on 2 November 2022).

[57] Monga, C. (2019), “Truth is the safest lie: A reassessment of development economics”, in Monga, C. and J. Lin (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Structural Transformation, Oxford University Press, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198793847.013.29.

[26] Moreland, W. (2019), The Purpose of Multilateralism: A Framework for Democracies in a Geopolitically Competitive World, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/FP_20190923_purpose_of_multilateralism_moreland.pdf.

[36] Mottley, M. (2022), The Developing World in a Turbulent Global Financial Architecture: The 6th Annual Babacar Ndiaye Lecture, CNBC Africa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLT1YMJ0jM4.

[21] Mugobo, V. and M. Mutize (2016), “The impact of sovereign credit rating downgrade to foreign direct investment in South Africa”, Risk Governance & Control: Financial Markets & Institutions, Vol. 6/1, pp. 14-19, https://doi.org/10.22495/rgcv6i1art2.

[42] Musiitwa, J. (2012), “New game changers in Africa’s development strategy”, Development, Vol. 55/4, pp. 484-490, https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2012.84.

[25] Ndulu, B. et al. (2007), The Political Economy of Economic Growth in Africa, 1960-2000, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511492648.

[64] Ndung’u, N. and L. Signé (2020), “The Fourth Industrial Revolution and digitization will transform Afica into a global powerhouse”, in Capturing the Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Regional and National Agenda, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ForesightAfrica2020_Chapter5_20200110.pdf.

[75] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Guide for Development Co-operation: Strengthening the Role of Development Co-operation for Sustainable Investment, OECD Development Policy Tools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7f251bac-en.

[17] OECD (2022), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023: No Sustainability Without Equity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fcbe6ce9-en.

[28] OECD (2022), Multilateral Development Finance 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9fea4cf2-en.

[73] OECD (2022), Total flows by donor (ODA+OOF+Private): ODA and ODA%GNI by donor [DAC1] (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=113263 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

[65] OECD (2021), Development Co-operation Report 2021: Shaping a just digital transformation, https://doi.org/10.1787/ce08832f-en.

[47] OECD (2020), Development Co-operation Report 2020: Learning from Crises, Building Resilience, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6d42aa5-en.