Daphine Muzawazi

African Union Development Agency

Rita da Costa

OECD Development Centre

Daphine Muzawazi

African Union Development Agency

Rita da Costa

OECD Development Centre

African countries have made progress towards development goals and in institutional capacity building since the early 2000s. However, continental challenges persist, particularly industrialisation and economic competitiveness for job creation. Asymmetries in the international financial architecture make it more difficult for African countries to recover from the COVID-19 crisis, manage increasing debt service costs, finance much-needed investment in infrastructure for structural transformation and cope with the effects of climate change. Development co‑operation providers can help African nations by rethinking their approaches and tools. New models of mutually beneficial partnerships among equals should underpin development co-operation going forward.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Symerre Grey-Johnson of AUDA-NEPAD; and Lianne Guerra, Bakary Traoré and Federico Bonaglia of the OECD Development Centre for their input to this case study.

Development co-operation providers can support Africa’s industrialisation and productive transformation by helping to address the continent’s infrastructure deficit and supporting key agendas, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Given asymmetries in the international financial system, development co-operation providers should increase their support for debt relief and new approaches to debt treatment. They could facilitate dialogue between Africa and credit rating agencies and identify and support options to reallocate USD 100 billion of International Monetary Fund special drawing rights to developing countries.

New models of partnerships among equals are needed. They should provide a space and tools for Africa to co-create solutions, including through technology transfer and capacity building to help the continent adapt to new co-created rules and standards.

Unfortunately, the current international co-operation system has not produced the desired results for Africa’s development. The continent remains highly vulnerable to external shocks, and despite economic growth and poverty reduction at the continental level, significant gaps remain at the national level. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ramifications of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have exacerbated Africa’s challenges and demonstrated the vulnerability and limited resilience of a continent increasingly connected with the world. The pandemic led to increased government spending as revenues declined, leaving African governments with a heavy financial burden on top of structural difficulties.

The OECD’s Development in Transition (DiT)framework offers helpful guidance to development co‑operation actors wishing to support Africa’s long-term development in an increasingly complex world.1 This framework centres the rethinking of international co-operation in the current reality of increased global interconnections and international policy incoherence. DiT conceives development as a multidimensional, continuous (and reversible) process and takes into account vulnerabilities in developing countries that persist despite increased average income levels. DiT further calls for new metrics to better measure development progress and for new instruments and multi-actor partnerships.

Africa needs this renewed and holistic approach to co-operation to address internal structural difficulties, including the lack of regional integration and productive transformation, weak financial and technical capacity for policy and project implementation, persistently high levels of informality and low public revenue‑generation capacity, and significant illicit financial flows leaving the continent (AUC/OECD, 2019[1]). Domestic policies will be important to overcome these issues in the future. But in a highly interconnected world, national efforts are not enough.

Structural difficulties include the lack of integration and productive transformation, weak financial and technical capacity for policy and project implementation, persistently high levels of informality and low public revenue-generation capacity, and significant illicit financial flows leaving the continent.

Important institutional changes over the past 20 years, internationally and on the continent, laid the groundwork for transformative development. The African Union (AU) was established in 2002; the 2008‑09 financial crisis and emergence of new development actors led to the Group of Twenty (G20) being upgraded to leader level; and the AU charted a path forward by adopting Agenda 2063 and transforming the New Partnership for Africa’s Development into the African Union Development Agency, now known as AUDA-NEPAD. Yet Africa still faces many internal challenges to attaining inclusive and sustainable economic growth and delivering qualitative and quantitative transformative outcomes for its people (African Union, 2013[2]).

Development co-operation providers can step up support to accelerate productive transformation as an urgent priority. New forms of partnerships are needed to ensure that action on global agendas such as digital transformation and a green transition takes Africa’s needs into account. Any approach to co‑operation and partnerships must support Africa’s own efforts towards sustainable development, give Africa a meaningful place in global governance mechanisms to address shared challenges, adapt co‑operation and financing instruments to more complex scenarios, put adaptation to African contexts at its core, and see building resilience and self-sustainability as a key end goal.

The disappointing response to Africa’s pressing need for development finance following the COVID-19 crisis shows how asymmetries in the international financial system stymie the continent’s development progress. The international community must prioritise mobilising greater financing to enhance Africa’s capacity for sustainable development. Building Africa’s resilience also requires better rules and mechanisms. A reinvigorated and more inclusive international co-operation system can play a critical role in redressing asymmetries related to debt treatment, affordable access to finance, risk perceptions and the allocation of special drawing rights (SDRs). Overcoming those asymmetries would, in turn, help Africa’s own efforts to build back better.

Under current projections, it will take African countries more than five years to regain their pre-pandemic share (about 5%) of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). Africa’s debt, while relatively small, has increased rapidly in terms of its percentage of GDP since 2014; as of 2022, it is equivalent to 24.1% of African countries’ combined GDP (World Bank, 2022[3]). African debt service payments have also risen sharply in the last decade, partly due to higher interest payments on private loans. External debt costs rose by 1.1% of GDP on average between 2010 and 2019, offsetting nearly two-thirds of the average increase in tax levels over this period (OECD/ATAF/AUC, 2022[4]).

International co-operation and debt relief programmes such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the G20 Common Framework could help strengthen African countries’ balance sheets and their ability to repay debt in the medium term. However, there has been little progress in implementing the Common Framework. Moreover, despite the high risks of debt overhang, some developing countries have been reluctant to join these programmes out of concern that participation would trigger a credit rating downgrade. Such reluctance to participate in a debt relief initiative may also have a negative impact on a country’s long-term debt sustainability.

OECD countries could support the continent in its demand for debt relief and promote dialogue between credit rating agencies and the African public sector to review African countries’ credit rating indicators. As stressed by Senegalese President and AU Chair Macky Sall, such support could take the form of promoting better internal co-ordination among pan-African institutions and regional economic communities on standards within the region; strengthening Africa’s own rating agencies; and developing an African Investment Observatory to provide better information on African investment trends, ecosystems and opportunities (International Economic Forum on Africa, 2022[5]).

SDRs provide a much-needed injection of liquidity without adding to debt burdens. Africa is advocating for a reallocation of USD 100 billion in SDRs to low- and middle-income countries after the historic issue of USD 650 billion in SDRs. Africa received only 5% of this total, or its quota of USD 33 billion. With official development assistance (ODA) expected to stagnate or decrease in the coming years, the reallocation of SDRs can strengthen low- and middle-income countries’ ability to react to global crises by providing them with more financial breathing space.

The Summit on the Financing of African Economies, convened by France in 2021, also endorsed a reallocation (French Presidency, 2021[6]). However, there has been little progress (Laub and Dwyer, 2022[7]; Plant, 2021[8]; Plant, Hicklin and Andrews, 2021[9]). The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) efforts to absorb SDRs reallocation through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and its new facility, the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, are constrained by limitations such as eligibility criteria (Vasic-Lalovic, 2022[10]). Moreover, no decision has been taken at the international level regarding other channels of reallocation. Development partners should explore further options for channelling reallocated SDRs through key African institutions. The AU has suggested the African Development Bank as a prescribed holder of SDRs (Adesina, 2022[11]).

Advanced economies should commit to rapidly channel at least 30% of their SDRs to reach the global ambition of USD 100 billion, thus providing additional reserves to help drive the post-pandemic economic recovery and underpin the green transition. Looking forward, it will be important for development partners to remain firmly committed to not reporting SDRs as ODA in DAC statistics (OECD, 2022[12]) if such a reporting would have a negative impact on current ODA efforts in terms of trade-offs.

It will be important for development partners to remain firmly committed to not reporting SDRs as ODA in DAC statistics (OECD, 2022[12]) if such a reporting would have a negative impact on current ODA efforts in terms of trade-offs.

For their part, African governments should commit to an open and transparent process that will allow citizens, civil society organisations and legislatures to clearly follow how SDRs are used. This would include disclosing plans publicly, periodically publishing progress reports, and assessing how the implemented activities and results align with objectives. For now, most African governments have disclosed their plans for these new resources, which range from boosting their foreign exchange reserves to enhancing health and social protection systems and paying off debt (Kerezhi and Gbemisola, 2022[13]). If the reallocation of SDRs is made through key African institutions, development partners could also provide capacity for African countries and institutions to undertake such reporting on how SDRs are used as well as support the creation of a common reporting framework that would facilitate the monitoring of SDR allocations.

Accelerating productive transformation is critical for creating quality jobs that reduce poverty and strengthening Africa’s economic resilience (AUC/OECD, 2019[1]). But Africa’s industrialisation and productive capacities remain vulnerable, gaps persist in the continental infrastructure and its ability to compete in international markets is limited. The continent’s share of European Union and US imports decreased from 2.4% in 2019 to 2.0% in 2020, whereas the share from Latin America and the Caribbean slightly increased. Africa’s access to wind energy, technology and domestic financing instruments is unequal and flawed. Creating productive employment can help lower poverty levels as limited fiscal space and the prevalent informal economy reduce the scope and efficiency of existing social protection systems (AUC/OECD, 2022[14]).

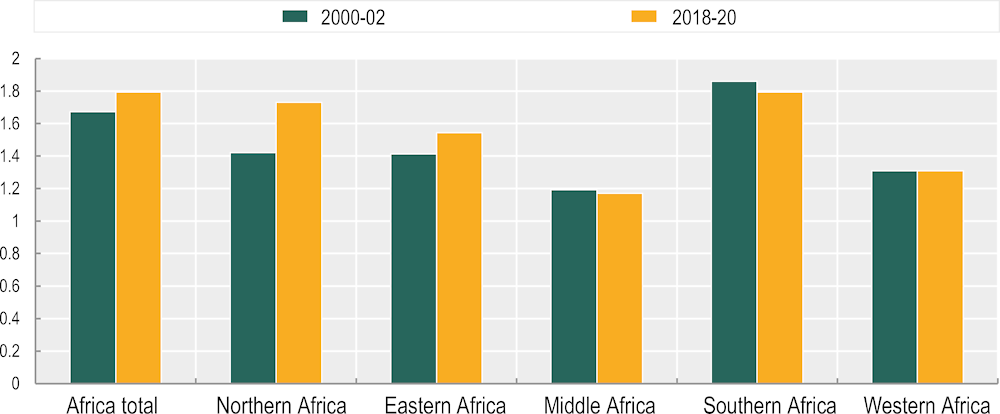

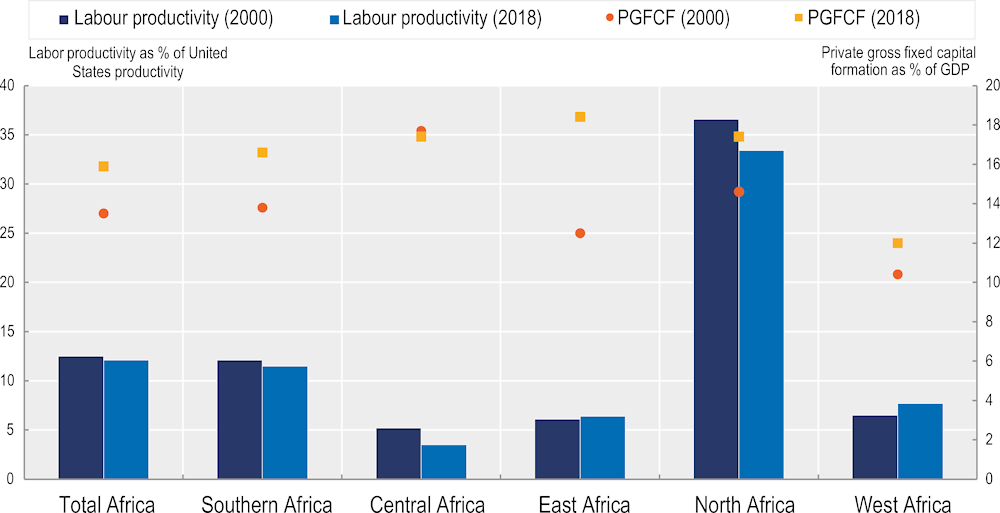

Africa was experiencing improved export diversification prior to the COVID-19 crisis, though there was a high level of heterogeneity in performance across sub-regions. North and East Africa led in terms of diversification; in the other sub-regions, export diversification had been decreasing or unchanged (Figure 21.1). At the same time, while private sector performance improved in most African sub-regions – as manifested proxied by an increase in gross private fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP over the 2000-18 period – this was not enough to reduce the gap in labour productivity relative to the United States (Figure 21.2). This impacts on Africa’s competitiveness at the global level and on Africa’s growth (OECD, 2022[15]).

Notes: The diversification index is computed by measuring the absolute deviation of a country’s trade structure from the world trade structure. This index assigns values between 0 and 1: A value closer to 1 indicates greater divergence from the world pattern. To better illustrate the change for Africa relative to the world, this figure uses the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development diversification index, which is why the maximum value is not on the scale from 0 to 1.

Source: Authors based on UNCTAD (2022[16]), Merchandise Trade Matrix in Thousands United States Dollars, Annual, 2016-2021 (database), http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=217476&IF_Language=eng.

Note: PGFCF: private gross fixed capital formation.

Source: Authors based on AUC/OECD (2019[1]), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2019: Achieving Productive Transformation, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1cd7de0-en.

ODA must continue to support Africa’s productive transformation by helping address the continent’s infrastructure deficit, which is one of the biggest constraints to income and productivity growth. Development partners could also help attract private capital and advanced technology to the continent. Development partners’ efforts to use ODA as a catalyst to direct more financing from financial markets and institutional investors towards supporting development are, in this sense, welcome.

ODA must continue to support Africa’s productive transformation by helping address the continent’s infrastructure deficit, which is one of the biggest constraints to income and productivity growth.

Development partners must also innovate, particularly by using aid differently. Their active support will be required in the design of new tools to finance the implementation of infrastructure projects, including project preparation facilities; public, private and multilateral partnerships; and the provision of sovereign guarantees to multilateral development banks to leverage their balance sheets (Capital Adequacy Frameworks Panel, 2022[17]).

In a scenario with more players, development partners should support the development of a common reference framework and standards to reduce transaction costs and facilitate project preparation and implementation. The G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment and the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa Quality Label are useful tools in this regard.

In addition, development partners should rely more on regional partners such as the African Union Commission and AUDA-NEPAD to promote greater private sector investment and foster national ownership of economic transformation processes. Contextualising the specific challenges of the African continent also remains a challenge. Development partners could support a harmonised vision through the operationalisation of Agenda 2063 and specifically its goal of economic transformation. Greater synergies between traditional providers and providers from emerging market economies, with greater alignment to Agenda 2063 and the SDGs, are necessary.

Development partners should rely more on regional partners to promote greater private sector investment and foster national ownership of economic transformation processes.

In this respect, active support of the transformative agenda of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and its implementation is a priority. The AfCFTA holds great promise, especially given the persistent challenges and polarisation in the international trading system and the political backlash against globalisation in some parts of the world. The AfCFTA is a crucial engine for continental integration and the development of regional value chains. Its implementation will likely generate trade-offs and will require building greater resilience at country level to internal and external shocks. Changing the current patterns of Africa’s participation in global value chains is necessary to bring about a productive transformation that accelerates economic recovery and creates quality employment and social upgrading.

Africa is often portrayed as a continent of great challenges. It is essential to build a vision of Africa as a continent of great promise. Addressing structural problems and asymmetries related to financing as well as paying attention to governance issues in Africa would enable progress. Resilience and self-sufficiency should be at the core of Africa’s quest for sustainable development and of development partners’ efforts on the continent.

Africa needs better and mutually beneficial partnerships that are more conducive to its development efforts. The continent also needs to foster a debate that contributes to addressing the asymmetries at the multilateral level that undermine Africa’s development potential and its efforts to determine its destiny. To this end, it will be important to solve the lack of representation of Africa in key global decision‑making institutions and processes. AU Chair Sall, among others, has called for the AU to have a permanent seat in the G20.

At the outset, development partners should also embed African countries and constituencies into actions to achieve new global priorities for just green and digital transitions. Renewed partnerships should not be framed as donor-recipient relationships but as partnerships of equals. They should include any country, regardless of its income level, that is willing and able to contribute and benefit from the partnership according to its capacities, expertise and needs. For example, African experiences in areas such as climate change, security, responses to pandemics, migration, and the green and digital transitions could and should inform global efforts.

Finally, development partners should acknowledge the specific circumstances and specific endowments of African countries when establishing new partnerships. Supporting African countries to adapt to new standards and global priorities linked to the green and digital transitions will be essential to ensure that no country is left behind. Building capacities, allowing for adaptation to take place according to different timescales, strengthening other forms of international co-operation linked to technology transfer, adapting support to the specific endowments of Africa, and co-creating rules and standards will be crucial.

[11] Adesina, A. (2022), Development in a Context of Global Challenges: Experiences and Lessons from the African Development Bank, William G. Demas Memorial Lecture, African Development Bank Group, Abidjan, https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/dr_akinwumi_adesina_-_william_d._delma_memorial_lecture_june_14_2022_final.pdf.

[2] African Union (2013), “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want – Overview”, web page, https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview (accessed on 14 November 2022).

[14] AUC/OECD (2022), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2022: Regional Value Chains for a Sustainable Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2e3b97fd-en.

[1] AUC/OECD (2019), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2019: Achieving Productive Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1cd7de0-en.

[17] Capital Adequacy Frameworks Panel (2022), Boosting MDBs’ Investing Capacity: An Independent Review of Multilateral Development Banks’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks, Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, Rome, https://www.dt.mef.gov.it/export/sites/sitodt/modules/documenti_it/news/news/CAF-Review-Report.pdf.

[6] French Presidency (2021), Summit on the Financing of African Economies, French Presidency, Paris, https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2021/05/18/summit-on-the-financing-of-african-economies-1 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

[5] International Economic Forum on Africa (2022), Main Conclusions and Recommendations of the Forum, OECD/African Union/Republic of Senegal, Paris/Addis Ababa, Dakar, https://www.oecd.org/development/africa-forum/Africa-Forum-2021-Main-conclusion.pdf.

[13] Kerezhi, S. and J. Gbemisola (2022), “Data Dive: Special drawing rights”, https://data.one.org/data-dives/sdr/#sdr-holdings (accessed on 14 December 2022).

[7] Laub, K. and S. Dwyer (2022), “Advocating for SDR reallocation: A call to action”, Donor Tracker Commentary, https://donortracker.org/insights/advocating-sdr-reallocation-call-action (accessed on 13 December 2022).

[15] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6da2159-en.

[12] OECD (2022), Summary Record of the Meeting of the Working Party on Development Finance Statistics (WP-STAT), OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/STAT/M(2021)3/FINAL/en/pdf.

[4] OECD/ATAF/AUC (2022), Revenue Statistics in Africa 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ea66fbde-en-fr.

[8] Plant, M. (2021), “How to make an SDR reallocation work for countries in need”, Center for Global Development blog, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/how-make-sdr-reallocation-work-countries-need (accessed on 13 December 2022).

[9] Plant, M., J. Hicklin and D. Andrews (2021), Reallocating SDRs into an IMF Global Resilience Trust, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/reallocating-SDRs-IMF-global-resilience-trust_.pdf.

[16] UNCTAD (2022), Merchandise Trade Matrix in Thousands United States Dollars, Annual, 2016-2021 (database), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva, http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=217476&IF_Language=eng.

[10] Vasic-Lalovic, I. (2022), The Case for More Special Drawing Rights: Rechanneling Is No Substitute for a New Allocation, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, DC, https://www.cepr.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Vasic-Lalovic-2022-PDF.pdf.

[3] World Bank (2022), International Debt Statistics (database), https://datatopics.worldbank.org/debt/ids/regionanalytical/MNA# (accessed on 14 November 2022).

← 1. For further details, see: https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-in-transition.htm.