Samantha Custer

AidData

Ana Horigoshi

AidData

Kelsey Marshall

AidData

Samantha Custer

AidData

Ana Horigoshi

AidData

Kelsey Marshall

AidData

How can DAC members deploy resources, broker partnerships and contribute expertise in ways that play to their strengths, complement local priorities and help leaders in the Global South deliver development progress for their countries? This chapter offers some answers based on the responses of some 8 000 public, private and civil society leaders across 141 countries to two major AidData surveys conducted in 2020 and 2022. It reviews the leaders’ own assessments of their country’s progress towards its development goals and the obstacles they see to prioritising and implementing reforms. The responses to the surveys summarised in the chapter also suggest how DAC members might better play to their strengths and maximise their influence with and value to Global South leaders.

To better position themselves as preferred partners, DAC members must be responsive to local priorities, plan for long-term sustainability, and structure assistance to complement and incentivise local reforms.

Public, private and civil society sector leaders in developing countries want international assistance to address systemic barriers to progress such as high levels of corruption and poor financial management, according to survey findings.

Countries in the Global South are not seeking to work exclusively with specific providers. They look for the comparative advantage of each international partner and see DAC members as especially well-positioned to help tackle governance and rule of law issues critical to their long-term development. have more choices of development partners.

Global South leaders express the greatest discontent with their countries’ lack of progress in achieving the stated priority goals of job creation and government accountability, though degrees of satisfaction varied between political elites in democratic countries and counterparts in autocracies.

Leaders’ commitment to growth and development is an essential precondition for low- and middle-income countries to achieve their goals (Dercon, 2022[1]). By paying attention to what their in-country partners say they want to achieve and what they need to make reforms happen, development co-operation providers increase the odds that their investments bear tangible fruit. Moreover, development co-operation providers seen as being aligned to national development strategies may gain a performance dividend as they tend to be considered more influential and helpful by leaders in low- and middle-income countries (Custer et al., 2021[2]). Yet providers often have imperfect information about what their counterparts in the Global South view as the key constraints to progress, the attributes of preferred partners and comparative advantages.

This chapter explores a single overarching question: How can DAC members deploy resources, broker partnerships and contribute expertise in ways that play to their strengths, maximise their influence and help leaders in the Global South deliver development progress for their countries? This question is timely because DAC donors must navigate an increasingly crowded and complex development co-operation marketplace (Custer et al., 2021[2]). Leaders in the Global South have a wider choice of prospective partners and sources of capital to bankroll their development than ever before. This includes concessional development assistance (grants and no interest or low-interest loans) to increasingly accessible private sector capital markets and less concessional assistance such as higher interest loans and equity investments by sovereign creditors like China, among others. Yet, even as there are more choices of partners, countries are still grappling with a formidable funding shortfall, estimated at USD 3.9 trillion as of 2020, to realise the Sustainable Development Goals (OECD, 2022[3]). Moreover, there is ample demand from leaders in the Global South to tap into the resources and expertise of DAC donors as their countries chart their own paths to realise a future that is “fairer, greener and safer” for everyone (OECD, 2019[4]).

This chapter triangulates the experiences of some 8 000 public, private and civil society leaders from 141 countries and contexts who shared their insights on development in their countries and their experiences working with international partners, including China, in 2 surveys conducted in 2020 and 2022 by AidData (Box 18.1). It first examines what respondents had to say about the domestic landscape for reform and their degree of satisfaction with their country’s progress in seven aspects of development. It then discusses the key constraints to progress identified by the leaders and their desired entry points for development co-operation (regardless of the donor) to support their reform efforts. The chapter then focuses on what the surveys revealed about how DAC members are perceived, emerging indications as to how providers might play to their strengths in ways that could be particularly beneficial for their in-country partners, and how DAC members can best position their assistance for maximum influence and resonance with Global South leaders.

Once every three years, AidData, a research lab at the Global Research Institute at William & Mary, a university in the United States, conducts an online Listening to Leaders Survey among public, private and civil society leaders across the Global South. This unique survey captures leaders’ perceptions, priorities and experiences over time on a set series of topics. This format has several advantages: comparability of responses to a common set of questions across survey waves; comparability between multiple cohorts of interest (e.g. sector, region, stakeholder group); comparability of perceptions of various government agencies or international development organisations using standardised scales; and the simultaneous capture of a breadth of data on diverse topics.

The 2020 Listening to Leaders Survey on global development priorities, progress and partner performance was conducted on line via Qualtrics between June and September 2020. Based upon the World Bank’s income group classifications in June 2020, the survey was fielded in 29 low-income countries, 50 lower middle-income countries and territories, 55 upper middle-income countries, 3 countries that had graduated to high-income status (previously middle-income and remained in the sampling frame), and 4 subnational areas (Puntland (Somalia), Kurdistan Region (Iraq), Somaliland (Somalia), Zanzibar (Tanzania). A total of 6 807 leaders shared their experiences via the 2020 survey wave.

Respondents identified the type of organisation they represent, their substantive area of expertise, and the development partners that provided advice or assistance between 2016 and 2020 (out of a list of more than 100 bilateral aid agencies, including most Development Assistance Committee [DAC] members, and multilateral organisations). Respondents came from six stakeholder groups: executive branch officials (44%); civil society leaders (19%); local representatives of development partners (13%); university, think tank and media representatives (10%); private sector leaders (6%); and parliamentarians (5%). They represented 23 areas of development policy and diverse regional perspectives: 34% were from sub-Saharan Africa; 20% from Latin America and the Caribbean; 17% from Europe and Central Asia; 13% from East Asia and the Pacific; 9% from South Asia; and 7% from the Middle East and North Africa.

In July and August 2022, AidData used its Listening to Leaders sampling frame to field a special online Perceptions of Chinese Overseas Development Survey to gauge how African leaders in 55 low- and middle-income countries and subnational areas view several of the largest development partners, among them the People’s Republic of China, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. The overall response rate was 4.1%, with 861 of the 21 278 invitees participating. The breakdown of respondents was 375 government officials (44%), 185 civil society leaders (21%), 128 university or think tank leaders (15%), 108 local representatives of development partners (13%), 43 private sector leaders (5%), and 21 parliamentarians (2%).

AidData is expanding the survey to additional regions, and results are expected to be available in mid‑2023.

In the 2020 survey, respondents identified sufficient jobs and accountable institutions as among the most important problems they want to solve for their constituents (Custer et al., 2021[2]). These topped the list among survey respondents across geographic regions, organisational type and gender, although the discontent was the strongest in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa. These two priorities were also consistent over time, with respondents identifying them as the most important problems to be solved in the previous leaders survey in 2017 (Custer et al., 2018[5]).

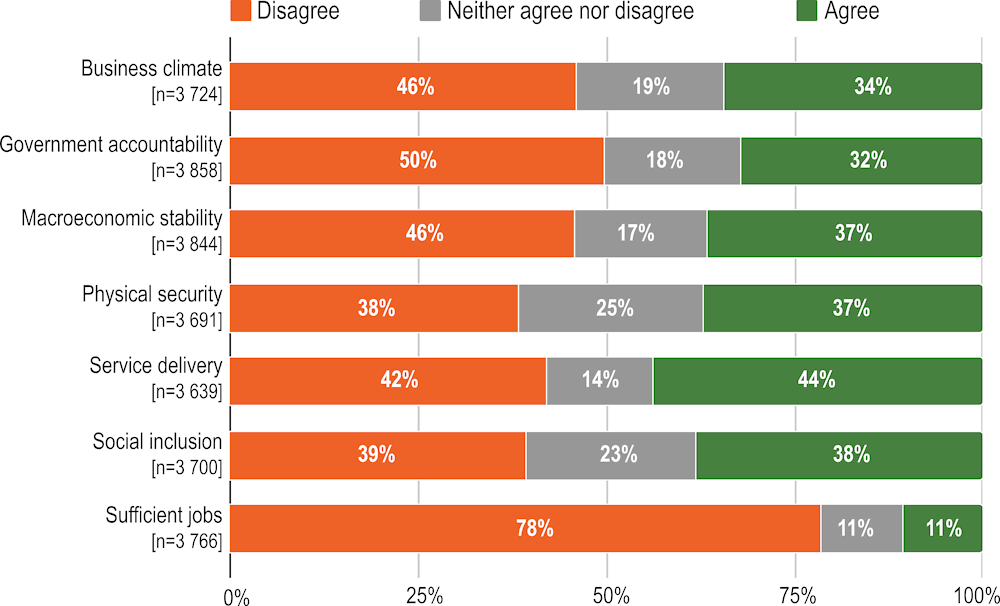

Yet, countries do not always achieve the outcomes they want just because leaders identify something as a priority or donors agree to devote financing to these areas. Nearly 80% of respondents disagreed with the statement that their country had generated sufficient jobs to keep the local workforce productively employed between 2016 and 2020, and 50% disagreed that the government was transparent and accountable to its citizens (Figure 18.1) (Custer et al., 2022[6]).

Notes: Respondents were asked if they agree, disagree, or neither agree nor disagree with seven different statements about their country between 2016 and 2020. The development policy areas covered were accountability (an open and accountable government); jobs (enough to keep the workforce productively employed); services (consistent delivery of basic public services); inclusion (development policies inclusive of all social groups); macroeconomics (a macroeconomic environment stable enough to foster sustainable economic growth); business (a favourable business environment for the private sector); and security (basic physical security). Responses of those who said they preferred not to give an answer to a particular question are excluded.

Source: Custer et al. (2022[6]), Aid Reimagined: How Can Foreign Assistance Support Locally-led Development?, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/aid-reimagined-how-can-foreign-assistance-support-locally-led-development.

Respondents from democratic countries were more optimistic about their government’s accountability than were those from autocracies, but the reverse was true when asked about progress in generating jobs (Custer et al., 2022[6]). This may reflect divergent priorities, in that autocracies may prioritise jobs for citizens to maintain regime stability while democracies may focus on accountability and trustworthiness to appeal to voters at the ballot box. Leaders’ subjective responses largely track objective measures of their country’s technocratic governance. Respondents from countries with objectively higher levels of development, better equipped bureaucracies and lower social inequality reported stronger progress on development outcomes. By contrast, leaders from fragile contexts reported lower levels of progress, reinforcing the concern that poor governance and fragility can become “traps” that stymie progress and enmesh countries in a low-growth equilibrium from which it is hard to escape (Collier, 2007[7]; Andrimihaja, Cinyabuguma and Devarajan, 2011[8]).

What might be driving this apparent disconnect between aspiration (i.e. what leaders say they want to achieve) and reality (i.e. what countries have been able to achieve)? The gap could be a consequence of constrained political support, insufficient resources, or limited capacity to effectively design and implement reforms. Alternatively, this dynamic might reflect a mismatch between the reforms being pursued by countries and what might spur meaningful improvements in performance, particularly if governments adopt reforms primarily to please external donors (Pritchett, Andrews and Woolcock, 2012[9]).

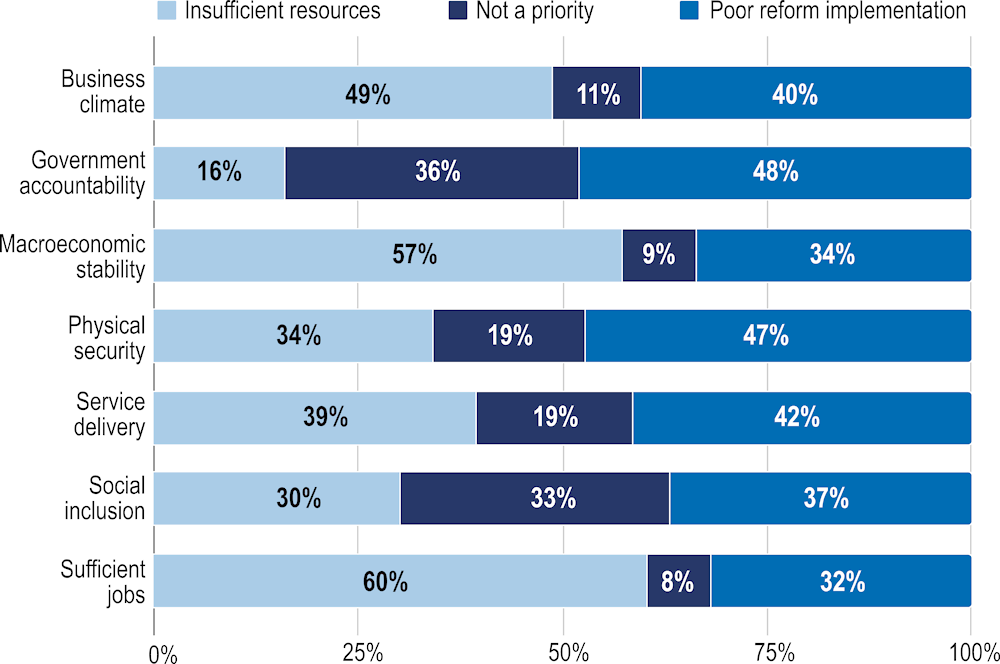

There may not be a one-size-fits-all explanation for the perceived lack of progress in accountability and job creation. Leaders’ responses indicate that the biggest hurdles to progress vary depending upon the nature of the problem they want to solve. Respondents who stated that their country had made insufficient progress in a given policy area were asked to select one of three reasons why this was the case: It was not a priority in national plans, there were insufficient resources or reforms were not implemented well (Figure 18.2).

There may not be a one-size-fits-all explanation for the perceived lack of progress in accountability and job creation.

For the two top areas of dissatisfaction – lack of progress in generating sufficient jobs and in ensuring accountable institutions – the majority of leaders in the 2020 survey (60%) selected insufficient resources as an impediment to delivering jobs (Custer et al., 2022[6]). Lack of resources was also cited, albeit to a lesser degree, as a key constraint on other facets of economic development, such as promoting a favourable business climate (49%) and ensuring macroeconomic stability (57%). These findings were consistent across countries regardless of geographic region or income level. It could be that governments are having a hard time crowding-in adequate capital and expertise to do what they say they want to do in their national plans. Alternatively, governments may identify something as a token, ostensible priority to appease a constituent or funder but are unwilling to devote the political or financial capital needed to take reforms forward.

By contrast, for the development area of promoting an open and accountable government, respondents identified lack of prioritisation (36%) and poor implementation of reforms (48%) as larger impediments than resourcing per se (Custer et al., 2022[6]). These were also the top reasons cited for limited progress on social inclusion. It is understandable why these might block reforms as enhanced accountability and social inclusion could threaten the livelihoods of those who benefit from the status quo (e.g. rent-seeking bureaucrats and dominant socio-economic groups). The status quo is much more difficult to dislodge in the absence of a strong grassroots push for change. Leaders from Latin America and the Caribbean were most adamant about this lack of prioritisation – noteworthy since many countries in the region are active members of the Open Government Partnership,1 which underscores the fact that there can be a difference between priorities in name and in practice.

Notes: Respondents who said their country had made insufficient progress in a given policy area were asked to choose one of three reasons why this was the case: insufficient resources, lack of prioritisation or poor reform implementation. The figure shows the percentage of respondents who selected each reason, disaggregated by development policy area.

Source: Custer et al. (2022[6]), Aid Reimagined: How Can Foreign Assistance Support Locally-led Development?, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/aid-reimagined-how-can-foreign-assistance-support-locally-led-development.

Respondents were asked to move from symptoms to root causes and drill down on why they had stated that a given area of development progress in their country was either not a priority, insufficiently resourced or had poorly implemented reforms. High levels of corruption (44-79%) and poor financial management (22-55%) were frequently cited as persistent constraints impinging on progress in all seven policy areas (regardless of which of the three impediments they previously identified) (Custer et al., 2022[6]).

Taken together, these results indicate that when insufficient resources derail a reform effort, this may often be a misallocation of resources – either by design (in the case of corruption) or oversight (in the case of poor financial management) and not necessarily lack of access to capital (Table 18.1). If anything, these findings underscore the importance of public financial management and anti-corruption programmes that build technical capacity and political will within governments and non-governmental watchdogs to support responsible use of public funds.

|

|

Poor tax laws |

Poor tax enforcement |

High levels of corruption |

Political instability |

Poor financial management |

Unprofitable for private sector |

Lack of access to international capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Accountability |

13% |

35% |

78% |

48% |

56% |

12% |

9% |

|

Jobs |

24% |

33% |

44% |

37% |

44% |

35% |

10% |

|

Services |

22% |

28% |

63% |

36% |

50% |

21% |

6% |

|

Inclusion |

30% |

34% |

49% |

23% |

53% |

38% |

6% |

|

Macroeconomics |

23% |

38% |

58% |

25% |

55% |

30% |

9% |

|

Business |

21% |

31% |

50% |

46% |

51% |

27% |

17% |

|

Security |

14% |

28% |

46% |

38% |

43% |

32% |

15% |

Notes: Respondents who selected “insufficient resources for reform” as their explanation for the lack of development progress were asked a follow-up question to determine why they thought resources were insufficient; they were asked to select three reasons from a list of seven key constraints or write in a response. The figure shows the percentage of these respondents who selected a given constraint across seven areas of development policy.

Source: Custer et al. (2022[6]), Aid Reimagined: How Can Foreign Assistance Support Locally-led Development?, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/aid-reimagined-how-can-foreign-assistance-support-locally-led-development.

Societal norms and group dynamics can also play an important role in hampering reform progress, either actively via resistance or passively via apathy. For example, respondents said there was not enough pressure from non-governmental actors pushing for progress in areas such as open and accountable government. This is a missed opportunity, as over 90% of leaders reported that they believe broad and diverse coalitions of actors outside of government – including non-governmental organisations, citizens, professional associations, media, think tanks and academia – could mobilise needed support for change (Custer et al., 2022[6]).

Even though leaders in the Global South have more options to finance development, DAC countries still have a critical role to play. Fewer than 10% of survey respondents indicated that they saw any given area of development policy as exclusively a domestic concern for countries to solve on their own (Custer et al., 2022[6]). Moreover, roughly 40% of leaders, on average, said their countries would benefit from a variety of contributions from international actors to support reforms, including financing and technical assistance on both design and implementation of programmes and policies as well as training, and awareness raising. But the optimal role for international development partners depended on the nature of the problem that domestic reformers were trying to solve and what they saw as the key constraints to progress.

In areas where insufficient resources were cited as the major pain point, such as in delivering sufficient jobs, the leaders’ responses emphasised the need for financial support, policy advice and training (Custer et al., 2022[6]). In areas where lack of prioritisation was the greater issue, such as with regard to government accountability, survey respondents were more interested in seeing donors mobilise domestic or international actors to exert pressure on those who were blocking reforms. Using a country’s classification on the Fund for Peace Fragile States Index as a departure point, AidData looked at whether and how levels of fragility affect attitudes towards international support. The analysis found that leaders in fragile contexts placed greater weight on the importance of external financing and mobilising pressure on those blocking reforms than did leaders in less fragile contexts. This held true across all policy areas except for jobs.

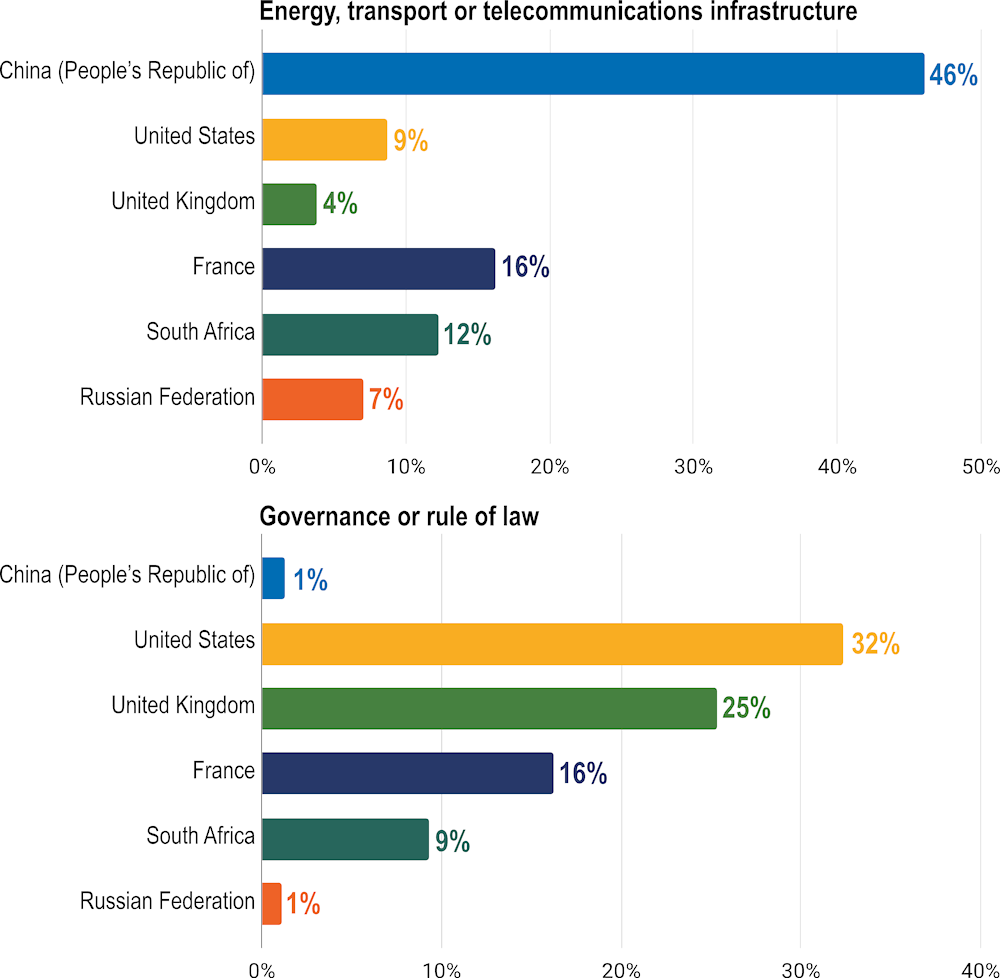

The Global South now has potential development partners other than DAC members to work with. But there remains a great degree of overlap between the top recipients of state-directed official development assistance from DAC members and the top recipients of aid from China, the largest non-DAC donor, as exemplified in aid to Ethiopia, Indonesia and Pakistan (Malik et al., 2021[10]; OECD, 2022[11]). Global South leaders do not view China and DAC members as an either-or option of development partner. Rather, the different providers are clearly seen as offering different comparative advantages. This view is evident in the responses to the 2022 AidData Perceptions of Chinese Overseas Development Survey which asked African leaders to identify their preferred partner in each sector out of six options: China, France, the Russian Federation, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States.

China was the most frequently selected preferred partner for energy, transport and telecommunications infrastructure projects by 46% of African leaders (Figure 18.3) (Horigoshi et al., 2022[12]). However, respondents gravitated to DAC donors in other areas of development. A case in point: Only 1% of African leaders selected China as their preferred partner in governance and rule of law projects compared to DAC members France (+15 percentage points), the United Kingdom (+24 percentage points) and the United States (+31 percentage points). DAC providers also had a comparative advantage in the eyes of African leaders in other areas related to health, education and social protection as well as natural resource management and environmental protection, though the spread between them and China was smaller.2

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of respondents who identified a given provider as their preferred development partner in each sector. Respondents could only select one of six proposed partners in each sector. Not all sectors included in the survey are included in the figure.

Source: Horigoshi et al. (2022[12]), Delivering the Belt and Road: Decoding the Supply of and Demand for Chinese Overseas Development Projects, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/delivering-the-belt-and-road.

The findings related to perceptions of China’s development assistance are broadly consistent with the results of the 2020 Listening to Leaders Survey, which covered additional geographic regions and development partners. Leaders identified each bilateral and multilateral development partner they had received advice or assistance from between 2016 and 2020. Respondents then assessed the degree to which each partner was influential in shaping policy priorities in their country and helpful in implementing policy reforms. Multilateral organisations and individual DAC donors tended to dominate the rankings of the most influential and helpful development partners in the social and environmental sectors (Custer et al., 2021[2]). In the realm of governance, China was influential but it was DAC donors and multilaterals that global leaders routinely turned to as among the most helpful in driving reforms in this area.

Multilateral organisations and individual DAC donors tended to dominate the rankings of the most influential and helpful development partners in the social and environmental sectors.

Leaders in the Global South have strongly signalled that they see DAC donors as comparatively well positioned to help address intractable public sector governance challenges either bilaterally or through effective multilateral partnerships. This support could involve channeling additional resources into existing programmes3 or starting new ones that focus on building the capacity of the executive branch to source, use and monitor public sector finances from various sources (e.g. official development assistance, domestic revenues, debt financing) in areas such as public financial management, anti-corruption programmes and open government initiatives. DAC donors could also build on existing networks of relationships with parliaments to promote legislation related to budget transparency and sustainable borrowing. They also could focus on strengthening the capacity of non-governmental actors (e.g. media, universities, civil society groups, the private sector) to play an important watchdog function through investigative journalism and participatory budgeting.

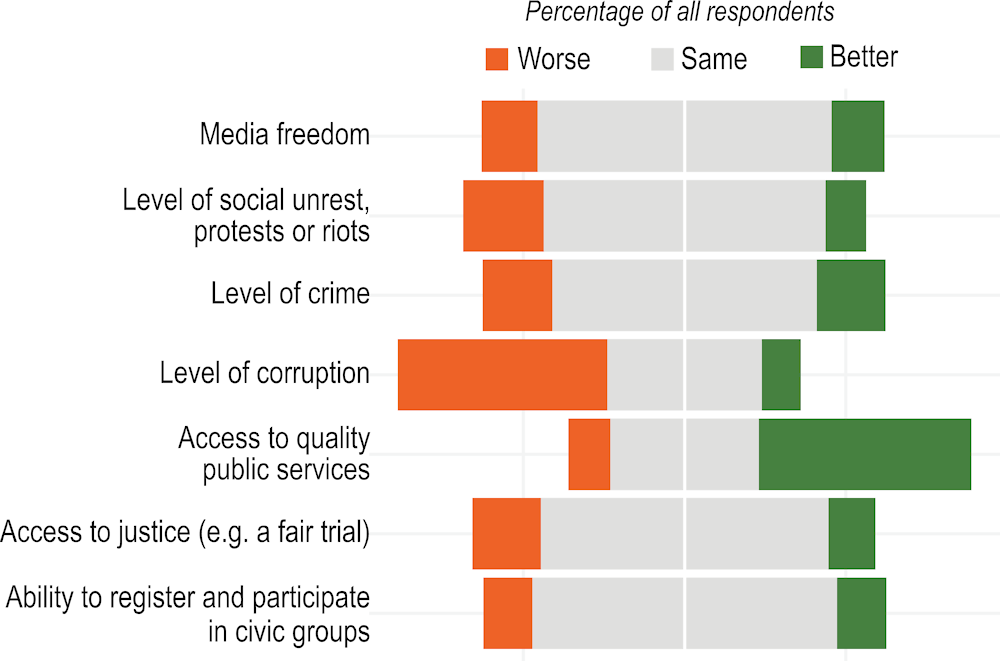

Support from DAC donors to help their partners in the Global South responsibly manage public sector resources is even more essential as countries are grappling with negative spillover effects associated with debt-financed development from sovereign creditors such as China as well as through private sector capital markets. Specific to China, African leaders reported several positive economic impacts and improved service delivery as a result of Chinese state-financed development projects, but these were at the cost of worsening corruption (Figure 18.4) (Horigoshi et al., 2022[12]).

Support from DAC donors in helping their partners in the Global South responsibly manage public sector resources is even more essential as countries are grappling with negative spillover effects associated with debt-financed development.

There may be several reasons for the uptick in corruption – Beijing’s use of non-disclosure clauses in its assistance, for example, as well as its unwillingness to participate in global aid reporting regimes and its practice of tying access to financing to the use of Chinese suppliers, labour and implementers rather than following open and competitive procurement processes when awarding contracts (Gelpern et al., 2021[13]; Horn, Reinhart and Trebesch, 2019[14]; Malik et al., 2021[10]). More broadly, debt financing from both China and private sector capital markets can expose countries to high repayment burdens once grace periods have lapsed and high interest rate payments kick in. This underscores the importance of cost-benefit analysis and fostering debt management capacities within governments to take sound financial decisions.4

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of respondents who said that China’s official finance projects had made a given governance condition in their countries either better, worse or about the same. While respondents used a five-point scale to rank their responses, the figure simplifies the options, collapsing “much worse” and “somewhat worse” into “worse” and collapsing “much better” and “somewhat better” into “better”. Respondents could also select “don’t know/prefer not to say”; the figure does not include those responses.

Source: Horigoshi et al. (2022[12]), Delivering the Belt and Road: Decoding the Supply of and Demand for Chinese Overseas Development Projects, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/delivering-the-belt-and-road.

The evidence from the two recent surveys points to the strong interest that leaders in the Global South still have in co-operating with DAC members, particularly in the areas of governance and rule of law as well as in efforts to build human capacity (e.g. education, health and social protection) and to protect the environment. However, to position themselves as preferred partners in a crowded marketplace, DAC providers should keep several additional insights in mind to maximise their influence and impact.

First, the views of leaders in the Global South are in lockstep with many of the principles of aid effectiveness to which DAC members aspire (GPEDC, 2016[15]; OECD, 2019[4]) but sometimes struggle to achieve in practice (Brown, 2020[16]; McKee et al., 2020[17]). Respondents to the 2020 Listening to Leaders Survey said the most influential and helpful donors were those that respected the self-determination of countries to set their own priorities, supported locally identified rather than externally imposed reforms, and ensured that their efforts are in step with those of other actors on the ground5 (Custer et al., 2021[2]). Respondents also emphasised the importance of building close working relationships with counterparts inside and outside of government as well as contributing substantive expertise.

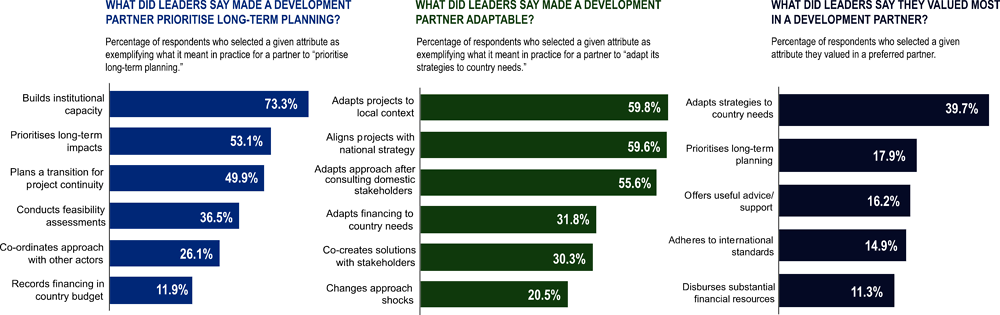

Second, and relatedly, when it comes to choosing partners, respondents to the Listening to Leaders Survey emphasised that they most valued donors that adapted their strategies to fit local needs, for instance aligning efforts to the national development strategy, ensuring projects were contextually appropriate and iteratively adapting approaches in consultation with key stakeholders (Custer et al., 2021[2]). Another attribute leaders looked for in their preferred partners was a commitment to long-term sustainability, for instance building local institutional capacity, prioritising long-term impacts over short-term gains and planning a transition to ensure project continuity after external assistance ended (Figure 18.5). Recognising the volatility of aid as donors face shrinking budgets, increased scrutiny from taxpayers and shareholders, and shifting priorities, the leaders in the Global South shrewdly recognised that their best chance to preserve hard-won development gains is to ensure that they have the capacity to independently sustain and build on the foundation laid with external partners whose engagement is time-limited.

Notes: The left panel shows the percentage of respondents who identified a given attribute as what they valued most in a preferred partner; the centre panel shows the results of two follow-on questions that asked what it means to adapt strategies to country needs; and the right panel shows responses about what it means in practice to prioritise long-term planning.

Source: Custer et al. (2021[2]), Listening to Leaders 2021: A Report Card for Development Partners in an Era of Contested Cooperation, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021.

Third, leaders also had strong preferences as to how development co-operation projects could be structured in ways that would be most conducive to supporting locally led reforms. DAC providers are well aligned with many of the attributes that their counterparts in the Global South look for in preferred projects. Survey respondents gravitated to projects that were transparent in the terms of assistance and expressed a preference for grants and low-interest loans compared to higher interest rate lending. They disliked tied aid and instead preferred projects that required procuring services and inputs from companies in the donor country. Nevertheless, alternative sources of capital may offer other advantages in the eyes of leaders in the Global South, particularly in regard to financing that supports larger rather than smaller dollar efforts and infrastructure projects compared to those focused on civil society strengthening or building the government’s administrative capacity to collect taxes.

Though DAC donors have been reluctant to tie assistance packages to policy reforms in recent years, survey respondents indicated that they would welcome these conditions in some instances (Custer et al., 2021[2]). Leaders were 1-2 percentage points more likely to choose projects with social, economic or democracy-related conditions than those with no conditions at all. They also expressed a greater preference for aid projects with regulations to reduce corruption, minimise environmental damage or protect workers from unfair labour practices than projects that did not require such reforms.

Though DAC donors have been reluctant to tie assistance packages to policy reforms in recent years, survey respondents indicated that they would welcome these conditions in some instances.

It is possible that leaders view these conditions and regulations as relatively toothless as long as aid agencies lack the political will or technical capacity to follow through in enforcing them (Li, 2017[18]; Kilby, 2009[19]). However, it is more likely that respondents may favour constraints that push forward reforms they were predisposed to support and for which they now can access new resources to motivate allies or undercut vocal detractors. In this respect, DAC countries have an opportunity to work “with the grain” of reforms (Levy, 2014[20]) that partner countries see as in their interest to pursue but also need the promise of additional resources as political leverage to offset domestic resistance to change.

The results of two novel surveys of leaders across the Global South provide insights into how DAC members can deploy resources, broker partnerships and contribute expertise in ways that correspond to the expressed needs and priorities of partner countries and deliver development progress. The evidence points to a strong demand on the part of leaders in low- and middle-income countries for assistance to address systemic barriers to progress in the form of corruption and poor financial management. Leaders’ responses also suggest that DAC members are seen to have comparative advantages in certain development policy areas, particularly regarding persistent governance challenges, that make them valued partners. It is clear that leaders place a premium on partners that are responsive to locally defined priorities, are willing to iteratively adapt assistance to find context-appropriate solutions and commit to plan ahead for long-term sustainability. There is an opportunity for DAC members to structure assistance in ways that do not impose undue burdens and instead strengthen the hand of counterparts to lock in desirable reforms.

DAC and non-DAC development partners alike would do well to heed the feedback from their counterparts in the Global South for two reasons. Not only is it the right thing to do from an aid effectiveness perspective. It is also the smart thing to do for savvy donors that want to maximise their standing with the leaders who will shape how their countries engage with foreign powers and aid institutions for years to come.

[8] Andrimihaja, N., M. Cinyabuguma and S. Devarajan (2011), “Avoiding the fragility trap in Africa”, Policy Research Working Paper, No. 5884, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5884.

[16] Brown, S. (2020), “The rise and fall of the aid effectiveness norm”, European Journal of Development Research, Vol. 32/4, pp. 1230-1248, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00272-1.

[7] Collier, P. (2007), The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

[5] Custer, S. et al. (2018), Listening to Leaders 2018: Is Development Cooperation Tuned-In or Tone-Deaf?, AidData at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2018.

[6] Custer, S. et al. (2022), Aid Reimagined: How Can Foreign Assistance Support Locally-led Development?, AidData at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/aid-reimagined-how-can-foreign-assistance-support-locally-led-development.

[2] Custer, S. et al. (2021), Listening to Leaders 2021: A Report Card for Development Partners in an Era of Contested Cooperation, AidData at the College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

[1] Dercon, S. (2022), Gambling on Development: Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose, Hurst, London.

[13] Gelpern, A. et al. (2021), How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/how-china-lends-rare-look-into-100-debt-contracts-foreign-governments.

[15] GPEDC (2016), Nairobi Outcome Document, Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, Paris, https://www.effectivecooperation.org/content/nairobi-outcome-document (accessed on 17 August 2022).

[12] Horigoshi, A. et al. (2022), Delivering the Belt and Road: Decoding the Supply of and Demand for Chinese Overseas Development Projects, AidData at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/delivering-the-belt-and-road.

[14] Horn, S., C. Reinhart and C. Trebesch (2019), “China’s overseas lending”, Kiel Working Paper, No. 2132, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiel, Germany, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/Christoph_Trebesch/KWP_2132.pdf.

[19] Kilby, C. (2009), “The political economy of conditionality: An empirical analysis of World Bank loan disbursements”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 89/1, pp. 51-61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.06.014.

[20] Levy, B. (2014), Working with the Grain: Integrating Governance and Growth in Development Strategies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199363803.001.0001.

[18] Li, X. (2017), “Does conditionality still work? China’s development assistance and democracy in Africa”, Chinese Political Science Review, Vol. 2, pp. 201-220, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-017-0050-6.

[10] Malik, A. et al. (2021), Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a New Global Dataset of 13,427 Chinese Development Projects, AidData at William & Mary, Williamsburg, VA, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/banking-on-the-belt-and-road.

[17] McKee, C. et al. (2020), “Revisiting aid effectiveness: A new framework and set of measures for assessing aid ’quality’”, Working Paper, No. 524, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/WP524-McKee-Mitchell-Aid-Effectiveness.pdf.

[11] OECD (2022), Development - Flows by provider (database), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeID=3&lang=en (accessed on 1 December 2022).

[3] OECD (2022), Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2023: No Sustainability Without Equity, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fcbe6ce9-en.

[4] OECD (2019), Development Co-operation Report 2019: A Fairer, Greener, Safer Tomorrow, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9a58c83f-en.

[9] Pritchett, L., M. Andrews and M. Woolcock (2012), “Escaping capability traps through problem-driven iterative adaptation (PDIA)”, Working Paper, No. 299, Center for Global Development, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2102794.

← 1. The Open Government Partnership (OGP) requires participating countries to submit an action plan, typically developed in a collaboration between the government and civil society representatives, that specifies concrete commitments to improve public sector transparency and accountability. The survey responses may suggest that leaders want to see more prioritisation in this policy area outside of the OGP or that sufficient prioritisation in this field looks different from OGP membership and efforts.

← 2. In both natural resource management and environmental protection, 9% of African leaders selected China as their preferred partner; approximately one-fourth of respondents selected one of the DAC members as their preferred partner in these areas.

← 3. For example, organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have well‑regarded public financial management programmes that tend to be under-resourced. DAC members could channel additional resources via these programmes or undertake complementary efforts to help build the capacity of line ministries to more effectively assess the full life cycle costs of projects (debt-financed or otherwise) to take into account economic, social and environmental considerations.

← 4. DAC members also provide loans to finance overseas development but at a decidedly lower cost to the borrower. A typical loan offered by China has a 4.2% interest rate and a repayment period of less than ten years and requires collateral. For more discussion, see: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/how-china-lends-rare-look-into-100-debt-contracts-foreign-governments. A comparable DAC donor offering carries a 1% interest rate and a repayment rate of 25 years and seldom includes collateral or procurement requirements. See: https://doi.org/10.1787/e4b3142a-en.

← 5. For example, respondents to the 2020 survey emphasised that helpful donors made the effort to align their implementation of policies, programmes and projects with the activities of other development co‑operation actors. See a discussion of the responses at: https://www.aiddata.org/publications/listening-to-leaders-2021.