This chapter assesses the outcomes of fiscal reforms that would disincentivise the use of virgin materials and encourage demand for secondary materials instead. It evaluates the expected environmental outcomes and economic consequences of implementing different sets of policies by modelling stylised policy scenarios. The results suggest that a fiscal reform that combines taxation on primary materials with subsidies for recycling and secondary materials would significantly reduce environmental impacts while achieving budget-neutrality. The chapter also lays the basis for a deeper going discussion of three fiscal interventions in Chapters 8 to 10.

Economic Instruments for the Circular Economy in Italy

7. Fiscal reform to reduce primary material demand and support secondary materials – modelling possible outcomes

Copy link to 7. Fiscal reform to reduce primary material demand and support secondary materials – modelling possible outcomesAbstract

7.1. Introduction

Copy link to 7.1. IntroductionPart I of this report assessed the current use of economic instruments in Italy and identified opportunities for potential intervention to enhance their effectiveness in promoting the circular economy transition, primarily based on available data and evidence from international good practices. Part II focuses on providing more detailed guidance on policy options to promote a fiscal reform away from virgin material demand and to strengthen markets for recycled and other recovered (secondary) materials (Chapter 7). It specifically explores policy guidance on three fiscal instruments that could further support this policy objective (Chapters 8-10).

Multiple options are available to policy makers to improve the use of economic instruments to support greater circularity and sustainability, including targeted reforms to individual economic instruments, the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies and wider environmental fiscal reforms. An environmental fiscal reform is understood as an improved alignment of taxes and tax-like instruments with environmental harm, coupled with using the generated revenues in socially productive ways, including potentially shifting the tax burden away from less desirable sources such as labour. In essence, an environmental fiscal reform involves: i) using market-based instruments in environmental policies to factor in the cost of environmental damage in prices paid by polluters; ii) raising public revenue; and iii) deploying it in a socially useful way (OECD, 2017[1]). Environmental fiscal reform generally involves tax reforms to internalise negative externalities and to generate price signals to redirect production, consumption and investment behaviour aligned with higher sustainability and circularity, as well as the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies (and the introduction of environmentally beneficial subsidies).

The topic of environmental fiscal reform has been discussed in EU countries for several decades. A first wave of fiscal reforms took place in the Nordic countries in the 1990s, followed by various efforts in France, the United Kingdom and Spain, among others. Progress in the introduction or application of economic instruments is often held back by obstacles of a political, political economy, economic or budgetary nature, including concerns over their impacts on competitiveness, distributional effects and affordability concerns, public resistance to new taxes, and the political costs of action (IEEP, 2014[2]). One concern is the erosion of the tax base: as the aim of environmental taxes is to reduce environmental damage, when successful, they will effectively erode their own tax base. There may be a case for striking a balance between achieving the objectives of an ecological transition while ensuring the stability of tax revenues (World Bank Group, 2022[3]; European Environmental Agency, 2022[4]).

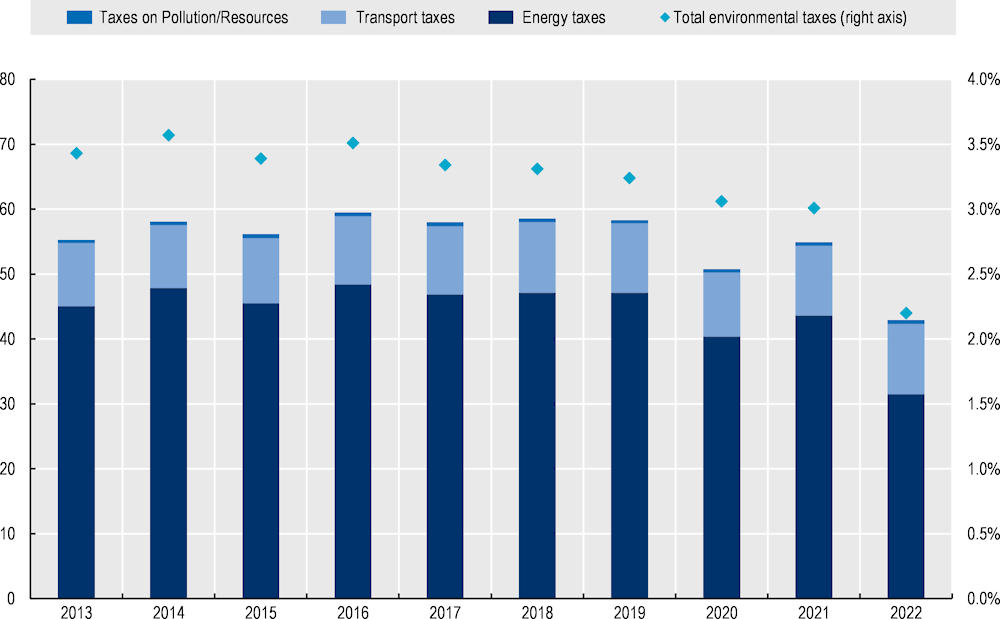

In Italy, environmentally related taxes generated EUR 42 billion in 2022 (Figure 7.1), corresponding to slightly more than 2% of GDP. The vast majority of revenues from environmentally related taxes and charges come from the energy sector (73%) and the transport sector (25%). In contrast, revenues from taxes and charges on pollution and resource use are minor, generating 1% of total revenues (i.e. mainly due to the environmental protection and preservation fee, destined for provinces, and the landfill tax).

Figure 7.1. Revenues from environmentally related taxes have been declining in Italy

Copy link to Figure 7.1. Revenues from environmentally related taxes have been declining in ItalyRevenues from environmentally related taxes, by type (in billion EUR, left axis) and total environmental taxes (as a percentage of GDP, right axis)

Note: In addition, there are several environmentally related taxes not reported in ISTAT or Eurostat databases, such as the fee on extractive activities.

Source: Elaboration of (ISTAT, 2022[5]).

The prospect of an environmental fiscal reform in Italy has been on the table for a long time, but little has been accomplished so far (Zatti, 2017[6]). Already in 2014, Law 2014/23 empowered the government to develop a fiscal reform for an ecological transition. More recently, environmental taxation reform has been highlighted as a priority in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan as part of broader fiscal reforms envisaged for the country. The increased availability of information and data today could support an environmental fiscal reform in Italy. The regular update of the Catalogue of Environmentally Harmful (EHS) and Favourable Subsidies (EFS) provides a wealth of insights on current environmentally harmful subsidies, which include both direct subsidies (e.g. to producers) and indirect subsidies (e.g. tax exemptions). Recently, a previous OECD-Italy project, also funded by the European Commission and administered by the Directorate-General for Structural Reform Support, aimed to support the development of a national policy agenda and action plan for environmental fiscal reform in Italy, considering options such as the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies, the reform of environmentally related taxes, and a broader fiscal reform (MASE - OECD, 2021[7]; MASE - OECD, 2021[8]).

Against this background, and in the context of the implementation of the National Strategy for the Circular Economy, there is strong interest in the Italian Government to develop fiscal measures that could help reduce the reliance on primary materials and accelerate the shift towards the use of recycled and other secondary materials. As mentioned earlier, Part II focuses on providing policy guidance in this area. In a first step, Chapter 7 evaluates the expected environmental outcomes and economic consequences of implementing different sets of policies that aim to reduce primary materials demand and promote secondary materials. The impacts are explored by modelling such policy scenarios within the OECD ENV-Linkages model (see Chapter 2 for the presentation of the baseline scenario and further details on the model).

This chapter is structured as follows:

Section 7.1 describes the methodology employed for the policy scenario simulations.

Section 7.2 presents results for a scenario that introduces subsidies to secondary materials and recycling.

Section 7.3 presents results for the fiscal reform scenario that combines the aforementioned subsidies with taxation on primary materials.

Chapters 8-10 of the report focus on providing in-depth guidance on a select number of instruments that may support the markets for secondary materials. After consultation with the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security (MASE),1 it was decided to look at one type of taxation and two types of fiscal incentives. The following instruments were chosen for further assessment:

Virgin material taxation applied to construction aggregates (Chapter 8).

Reduced VAT rates on products that contain recycled content (Chapter 9).

Corporate income tax credits to promote secondary (and other preferred) materials (Chapter 10).

7.2. Description of methodology employed for the modelling simulations

Copy link to 7.2. Description of methodology employed for the modelling simulationsTo explore the expected environmental outcomes and economic impacts for Italy of selected fiscal instruments, as well as possible synergies across measures, simulations were performed with the OECD ENV-Linkages model. This is a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model that links detailed projections of economic activity to material demand and environmental impacts, and adapted to produce baseline projections for Italy to 2040 (for business as usual, see Chapter 2 for more details). Two policy mixes are modelled and presented here:

Subsidies to support secondary materials, combining a subsidy for recycling and a subsidy for secondary metals production.

A budget-neutral fiscal reform for materials, combining subsidies to support the use of secondary materials and taxes on primary materials, using tax revenues to finance subsidies.

These policy mixes are derived from past work carried out at the global level (Bibas, Château and Lanzi, 2021[9]) which showed that the implementation of a global fiscal reform for materials (focused on metals and non-metallic minerals) would enable a relative decoupling of primary material use from economic growth. Model simulations showed that global primary materials use could be reduced by 27% for metals and 8% for non-metallic minerals, with an overall reduction in total primary material use of around 7% compared to the baseline for the year 2040.2 The shift from primary to secondary materials, resulting from the core policy reform, is projected to reduce the environmental impacts of global materials use, with an overall limited impact on economic activity (i.e. a loss of 0.2% of global GDP in 2040).

The subsidies scenario combines: i) a subsidy for recycling that corresponds to a 75% subsidy rate on the purchasing price of the recycling commodity for firms; and ii) a 25% subsidy on secondary metals production, in line with a previous study by Bibas, Chateau and Lanzi (2021[9]). The impact of the subsidies to support secondary materials is modelled on recycled metals.3 This choice was made due to the availability of data and given that industrial processes for metals recycling are widespread. Although there are limitations in generalizing the results to other materials (for instance, the assumption that secondary materials are readily available may not always hold, as the recycling of other materials is technically more difficult), the model may still help assess the expected trends as a result of fiscal incentives that support the transition away from primary materials.4

The fiscal reform for materials scenario combines taxes and subsidies to achieve budget neutrality. The tax rates on primary metals are designed to increase linearly from 2023 to reach the following levels in 2040: 7 EUR/tonne for iron ores, 14 EUR/tonne for copper ores, 36 EUR/tonnes for aluminium ores, 11 EUR/tonne for other non-ferrous metals ores and 4 EUR/tonne for non-metallic minerals.5 Tax rates have been calibrated for different metals according to the different environmental impacts. In addition, the same types of subsidies are implemented as the subsidies scenario, but the rate of the subsidy on secondary material production is adapted to 5% (compared to 25% in the first policy scenario). As detailed in section 7.4, this difference in the design of subsidies stems from the larger impact expected from the subsidies when combined with taxes.

Annex B contains further details on the modelling assumptions for these scenarios.

7.3. Subsidies to secondary metals and recycling

Copy link to 7.3. Subsidies to secondary metals and recycling7.3.1. Environmental outcomes (material demand and GHG emissions)

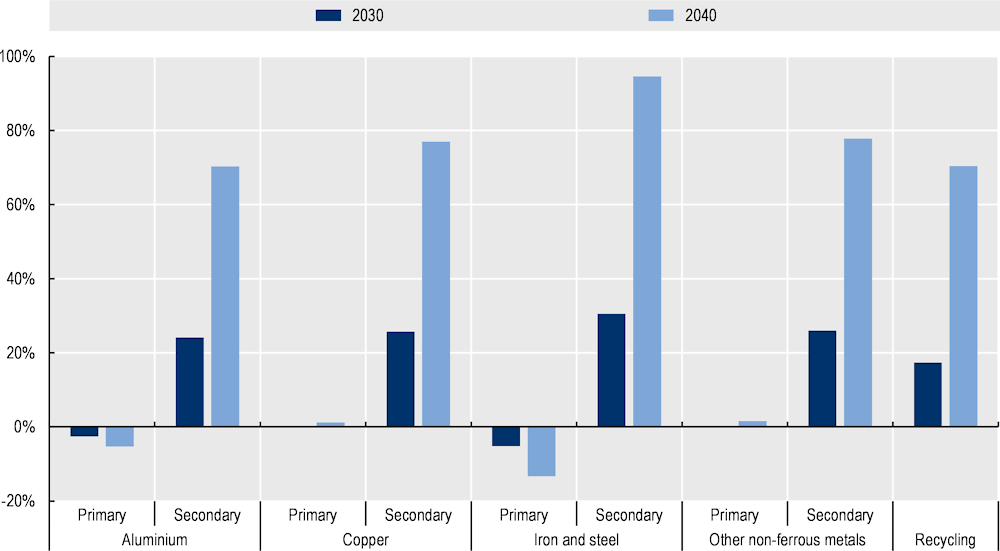

Copy link to 7.3.1. Environmental outcomes (material demand and GHG emissions)The subsidies modelled are expected to shift metal production towards more secondary materials. Based on the model, the production of secondary metals will increase by 70-95% in 2040 compared to the baseline (in blue in Figure 7.2). With the implementation of the subsidies, this corresponds to an increase of the share of secondary metals in production by 40-60% by 2040. In parallel, the demand for recycling (in red in Figure 7.2) is projected to increase by 70%.

Figure 7.2. The subsidies would lead to a shift towards higher secondary metals production and recycling

Copy link to Figure 7.2. The subsidies would lead to a shift towards higher secondary metals production and recyclingEvolution (percentage change) w.r.t. the baseline scenario of primary and secondary production for selected metals and the demand for recycling in 2030 and in 2040

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

While it is important to support the value chain for secondary metals to shift the balance of production towards secondary materials, subsidies alone do not significantly alter the overall demand for (primary and secondary) metals. Table 7.1 shows that total demand increases for all metals compared to the baseline as a response to materials made cheaper by the subsidies. Total metals demand in 2040 is expected to increase by 4-13% compared to baseline levels, despite a decrease in the production of most primary metals.

Table 7.1. Projected changes in primary and secondary metals production

Copy link to Table 7.1. Projected changes in primary and secondary metals productionShare in total production of primary and secondary metals, and percentage change for real gross output w.r.t. the baseline scenario, in 2040

|

Share in total production Baseline scenario |

Share in total production Subsidies scenario |

Evolution w.r.t. the baseline Subsidies scenario |

Total metal use evolution w.r.t. the baseline Subsidies scenario |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Iron and steel |

Primary |

65% |

46% |

-13% |

13% |

|

Secondary |

35% |

54% |

95% |

||

|

Aluminum |

Primary |

66% |

52% |

-5% |

5% |

|

Secondary |

34% |

48% |

70% |

||

|

Copper |

Primary |

93% |

89% |

1% |

6% |

|

Secondary |

7% |

11% |

77% |

||

|

Other non-ferrous metals |

Primary |

95% |

92% |

2% |

4% |

|

Secondary |

5% |

8% |

78% |

||

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

The impacts of the subsidies are different across the various metals. The main impact of the subsidies is (by design) an increase in the share of all secondary metals through the decrease in the price of secondary inputs (as shown in Table 7.1). Table 7.2 sheds light on the dynamics behind this evolution by examining the price of primary and secondary commodities as well as the costs to purchase mining inputs for the metal sectors. It is also relevant to look at the impacts of the subsidies on primary metals, which vary across metals. For ferrous metals (iron and steel) and aluminium, the subsidies scenario leads to a decrease in the price of primary metal production and thus of the purchase of mining inputs, whereas, for copper and other non-ferrous metals, the primary production price and purchase of mining inputs increase slightly. These results reflect: i) the different levels of subsidy rates across metals (calibrated to the metal-specific environmental impacts); ii) the limited substitutability of metal ores in primary production (generally, productivity gains can be found when using more capital); and iii) diverse levels of substitution from primary materials to secondary materials. For all metals, secondary metals production increases by an order of magnitude more than primary.

Table 7.2. Sectoral consequences

Copy link to Table 7.2. Sectoral consequencesPercentage change for metal ores w.r.t. the baseline in 2040

|

Metal sector Indicator |

Iron and steel |

Aluminum |

Copper |

Other non-ferrous metals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Costs to purchase mining inputs for the primary metal sectors (real value) |

-14% |

-6% |

1% |

1% |

|

Primary production (price) |

-3% |

-4% |

0% |

1% |

|

Secondary production (price) |

-35% |

-28% |

-24% |

-24% |

|

Primary production (real value) |

-13% |

-5% |

1% |

2% |

|

Secondary production (real value) |

95% |

70% |

77% |

78% |

Note: Prices are net of tax.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

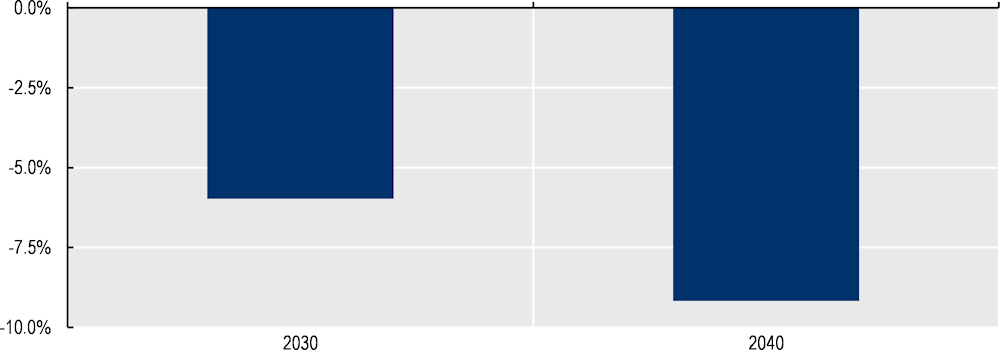

The slight increase in demand overall for metals explains why the shifts in materials use triggered by the subsidies lead only to a slight decrease (by 10% in 2040) in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to 2021 levels (Figure 7.3). As the activity in primary metal production decreases, so do the related GHG emissions. However, the model projects a concurrent increase in GHG emissions related to projected increases in secondary metals production due to a doubling of electricity demand and an electricity mix that is assumed to remain reliant on fossil fuels (mostly gas-fuelled power plants). Overall, the net effect is a reduction in GHG emissions, as the decrease in emissions related to primary metal production more than offsets the increase in emissions related to secondary metals production. Compared to the baseline (not shown in Figure 7.3), the subsidies will achieve a similar reduction in GHG emissions in 2040 from 2021 levels. This is mainly due to the fact that total demand in 2040 for metals increases by 4-13% compared to baseline levels, despite a decrease in primary materials production.

Figure 7.3. The subsidies would lead to a slight decrease in GHG emissions compared to 2021 levels

Copy link to Figure 7.3. The subsidies would lead to a slight decrease in GHG emissions compared to 2021 levelsPercentage changes w.r.t 2021

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

Model results for overall material demand to 2040 and the related implications for GHG emissions suggest that the design of the policy mix should pay attention to mitigating possible unintended effects of subsidies (or similar instruments such as fiscal incentives). Finished goods generally contain a combination of different materials, incorporating both primary and secondary materials. Thus, although the subsidies aim to support a shift to secondary metals, they could trigger a rebound effect on overall material demand, including primary demand. To address this, one option could be to implement policies that curb demand for physical goods (construction, manufactured goods), including through circular policies that seek to encourage reuse and repair, for example. Another option is to implement policies that disincentivise the use of virgin materials in production, such as targeted taxes. Section 7.4 illustrates the potential environmental outcomes and economic impacts from implementing material taxation in combination with subsidies in the context of a budget-neutral fiscal reform.

7.3.2. Economic implications

Copy link to 7.3.2. Economic implicationsThe modelling results indicate that the subsidies would lead to macroeconomic impacts that are small overall, as detailed below for impacts on gross domestic product (GDP) and employment, and impacts on public revenues.

The modelling exercise presented here investigates the possible macroeconomic and sectoral structural changes6 brought about by the measure and possible impacts on employment.

In response to the presence of subsidies for recycled materials, two main trends are expected: changes in production modes and demand patterns. First, firms are expected to adapt by using fewer raw and refined resource inputs in production, while shifting towards secondary materials. Economic activity in primary metals sectors is likely to decline, while the opposite effect is expected for secondary metals production. In parallel, demand patterns could change because of policy-induced variations in the relative price of goods or services, or when preferences evolve to adapt to the new economic environment (for example, due to greater consumer awareness), leading consumers to prefer goods that contain secondary materials. In turn, changes in demand patterns would lead to the expansion (or contraction) of certain economic activities. Changes in wages and thus household income are also likely to influence choices in savings or the labour force participation rate. Moreover, government spending on resource-efficient sectors may “crowd out” private investments in other sectors, negatively affecting output and employment within these sectors.

For the subsidies evaluated in this modelling exercise, the macroeconomic impacts are small overall. As shown in Table 7.3, GDP is projected to decrease by 0.4% in 2040 in Italy compared to the baseline. This is overall a slight decrease, corresponding to a decrease in the average growth rate over the 2021-2040 period of about 0.02% per year. The subsidies would lead to a minor increase in real wage rates and employment; these small impacts are aligned with the small share of the economy, represented by the metal processing sectors (about 3% of GDP).

Table 7.3. Summary of macroeconomic consequences

Copy link to Table 7.3. Summary of macroeconomic consequencesPercent change w.r.t. the baseline scenario for 2040

|

2030 |

2035 |

2040 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

GDP (constant PPP) |

-0.1% |

-0.2% |

-0.4% |

|

Household consumption |

-0.2% |

-0.4% |

-0.7% |

|

Employment (prs) |

0.1% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

Wage rate (relative to CPI) |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.1% |

|

All materials (volume) |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.1% |

|

Primary material intensity |

0.1% |

0.2% |

0.4% |

Note: CPI stands for Consumer Price Index, PPP stands for Purchasing Power Parities.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

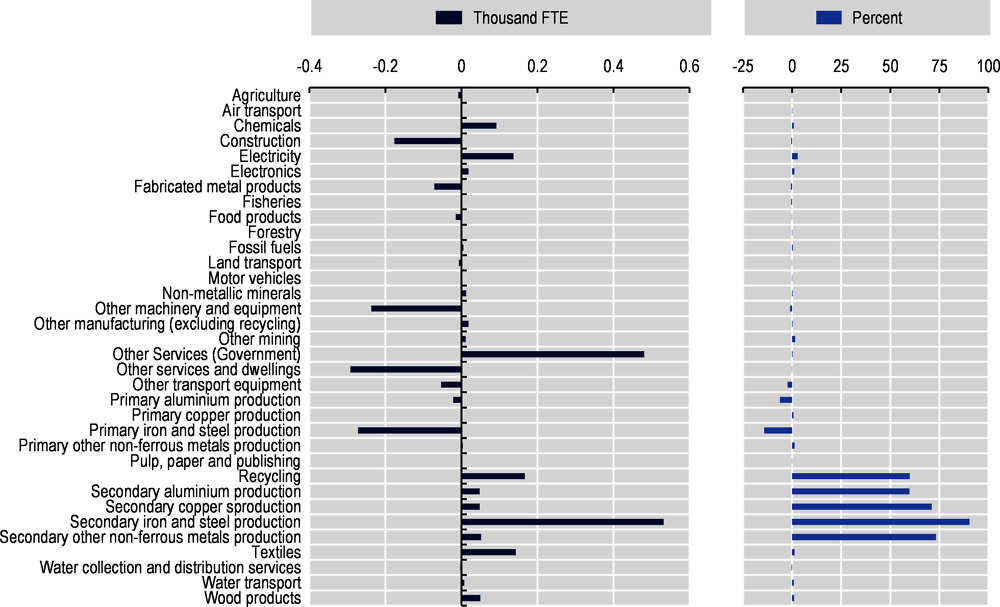

The macroeconomic and sectoral structural changes triggered by the subsidies affect employment in specific sectors, although the overall effect on employment is small (+0.1%), as shown in Table 7.3. The evolution of sectoral employment depends on the sector. It is not only determined by the level of activity within each industry but also by the substitution possibilities between primary and other forms of materials, and between labour and other inputs, both of which result from changes in their relative prices. As illustrated in Figure 7.4, the implementation of the subsidies has a positive effect on employment, mainly in the sectors targeted by the subsidies, i.e. secondary materials production and recycling (with an increase of 60-90% in employment in these sectors). Conversely, primary metals production is negatively affected (employment would either remain constant or decrease up to 14%). As these sectors employ less than 3% of the total workforce, the rest of the economy is only marginally affected by these policies.

Figure 7.4. The modelled subsidies are expected to support employment in targeted sectors

Copy link to Figure 7.4. The modelled subsidies are expected to support employment in targeted sectorsVariation of employment by sector w.r.t. the baseline scenario, in 2040

Note: FTE = Full-Time Equivalent.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

In terms of expected impacts on public finances, the modelled subsidies are of varying importance in the composition of government budgets. While subsidies on the consumption of recycling goods remain marginal (around 0.2% for Italy), the subsidies on secondary metals are important, around 1.7% of tax revenues. Even in 2017, before the implementation of the reform, the subsidies for secondary metals production already absorbed 0.4% of total tax revenues. From a macroeconomic perspective, the modelled subsidies would not significantly affect the composition of government revenues and expenditures.

Table 7.4. The subsidies in the composition of government budgets

Copy link to Table 7.4. The subsidies in the composition of government budgetsChanges in composition of government budgets, percentage of tax revenues

|

2021 |

2040 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline scenario |

Policy scenario |

||

|

Tax on labour income |

27.3% |

26.5% |

26.6% |

|

Tax on primary metals |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Subsidy on recycling good use |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.2% |

|

Subsidy on secondary metals production |

-0.4% |

-0.4% |

-1.7% |

|

Tax on primary metals production |

0.7% |

0.7% |

0.6% |

Note: Negative values correspond to subsidies.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

7.4. Fiscal reform to support secondary materials

Copy link to 7.4. Fiscal reform to support secondary materialsThe modelling results presented in the previous section suggest that subsidies alone could support shifts towards a higher demand for secondary materials in production processes, but without necessarily guaranteeing reductions in GHG emissions. The promise of environmental and climate benefits of higher circularity rests on the assumption that demand for primary materials will decline, that is, they are displaced by secondary materials (which are generally less impactful on the environment), or higher resource efficiency is achieved in production processes. However, the use of subsidies on their own may lead to higher consumption levels and a greater demand for (primary and secondary) materials overall, potentially cancelling out environmental and climate benefits.

For these reasons, the combination of subsidies and other incentive measures, with explicit, revenue-raising instruments, is generally preferable to amplify the benefits of the policies and thus achieve budget neutrality. This section explores the environmental outcomes and economic implications of a fiscal reform scenario that combines virgin material taxes with subsidies (on recycling and on secondary materials). As described in section 7.2, the fiscal reform for materials scenario includes taxes on primary metals (with different tax rates calibrated according to the environmental impacts and market prices) as well as a subsidy for recycling and a subsidy for secondary metals production. The latter was adapted to a lower value (of 5%, compared to 25% in the first policy scenario) due to the larger impact of the subsidies expected in this scenario.

7.4.1. Environmental outcomes

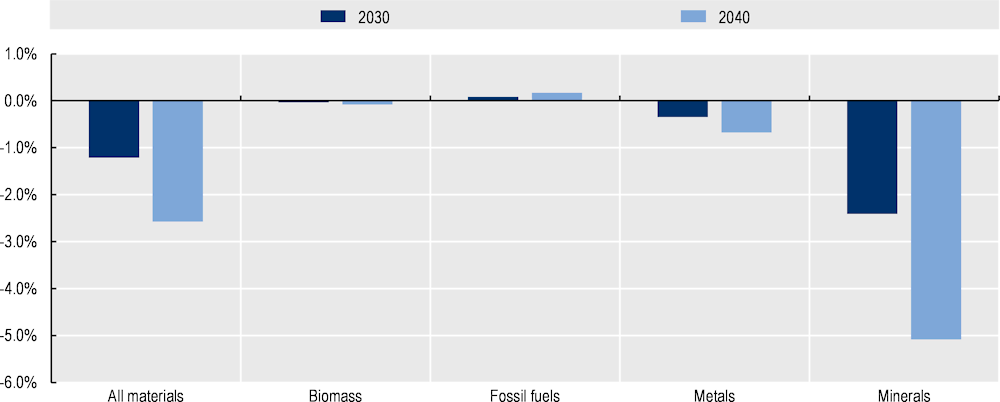

Copy link to 7.4.1. Environmental outcomesThe implementation of a fiscal reform for materials is projected to lead to an overall reduction of material use, while promoting the shift to secondary materials. Figure 7.5 shows the potential impacts on material use of the fiscal reform for materials described earlier. In particular, the implementation of primary material taxes could reduce the amount of materials used in the economy, mostly primary minerals and metals (i.e. the material groups targeted by the tax). In addition, there is a slight projected increase in fossil fuel consumption due to the energy requirements of producing domestic secondary materials.

Figure 7.5. The fiscal reform for materials would reduce the use of minerals and metals overall

Copy link to Figure 7.5. The fiscal reform for materials would reduce the use of minerals and metals overallEvolution of total (primary and secondary) material use (percentage change) w.r.t. the baseline scenario

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

The implementation of the fiscal reform also boosts the use of secondary metals across all represented categories. Table 7.5 shows the share of secondary metals in monetary values based on the fiscal reform (for materials) scenario and the baseline. Assessing the specific rates of growth for each material will depend on the level of policies implemented, as well as the differential in prices between material inputs in the production of goods. The overall result is that the share of secondary materials is boosted by the tax imposed on primary materials and the subsidies introduced for secondary materials and recycling.

Table 7.5. Evolution of secondary metals in the fiscal reform for materials scenario

Copy link to Table 7.5. Evolution of secondary metals in the <em>fiscal reform for materials</em> scenarioPercentage share of secondary sectors in real gross output.

|

2021 |

2030 |

2040 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Baseline |

Fiscal reform for materials |

Baseline |

Fiscal reform for materials |

|

|

Iron and steel |

33.2% |

33.9% |

36.0% |

34.6% |

39.3% |

|

Aluminium |

32.9% |

33.3% |

34.7% |

33.6% |

36.9% |

|

Copper |

6.8% |

6.7% |

7.2% |

6.8% |

7.9% |

|

Other non-ferrous metals |

5.2% |

5.0% |

5.3% |

4.9% |

5.7% |

Note: These shares are based on the output of the sectors in value and thus are different from shares in metal content.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

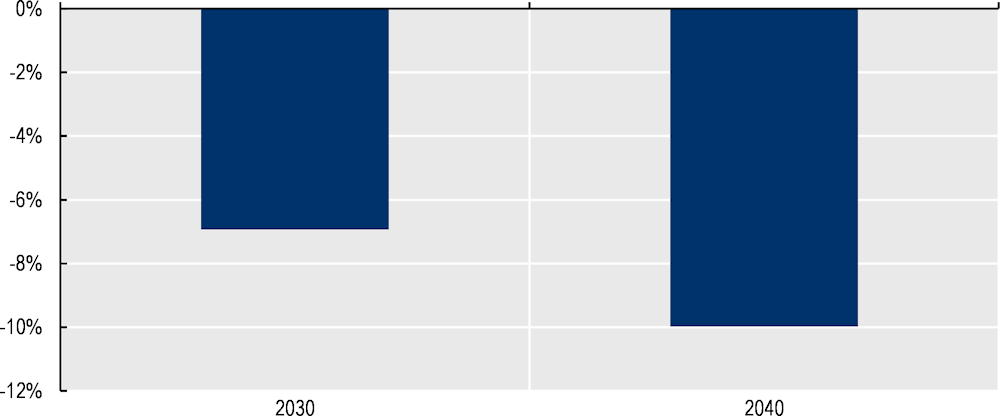

The combination of taxation for primary materials and subsidies for recycling and secondary materials would lead to a greater decrease in GHG emissions (compared to the subsidies only scenario) of around 10% in 2040 compared to 2021 (see Figure 7.6). Nevertheless, the still significant GHG emissions linked to the use of secondary metals underscore the importance of implementing circular economy policies that focus on improving resource efficiency, for example, by encouraging reuse and repair, which could lead to greater reductions in GHG emissions than substituting primary metals with secondary metals.

Figure 7.6. GHG emissions are projected to decrease as a consequence of the fiscal reform for materials scenario

Copy link to Figure 7.6. GHG emissions are projected to decrease as a consequence of the <em>fiscal reform for materials</em> scenarioPercentage changes w.r.t 2021

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

The results for Italy are aligned with previous findings on the expected outcomes of a fiscal reform for materials (Bibas, Château and Lanzi, 2021[9]), which showed that global primary materials use could be reduced by 27% for metals and 8% for non-metallic minerals compared to the baseline for the year 2040, leading to GHG emissions savings. However, the results showed that OECD countries, and particularly OECD Europe, showed the lowest reduction globally. This result is likely to stem from the specific characteristics of countries in the region, including their material endowment, material use, and extraction levels.

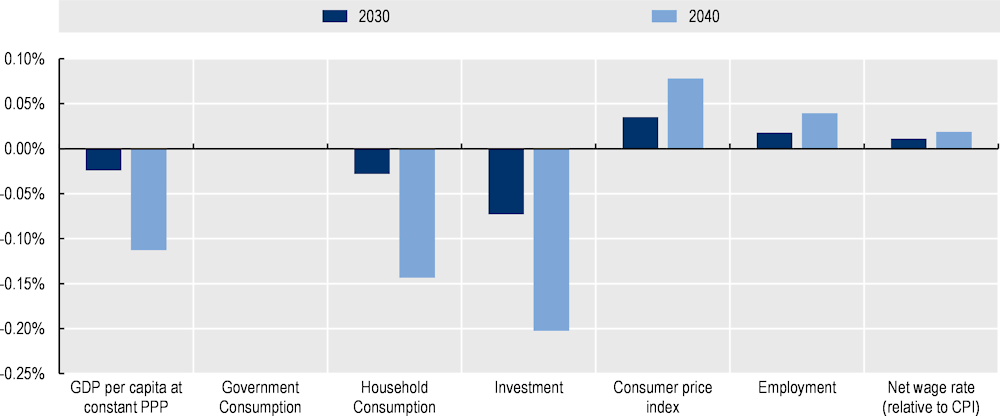

7.4.2. Economic implications

Copy link to 7.4.2. Economic implicationsThe implementation of the fiscal reform scenario has a negligible impact on macroeconomic indicators. For most of the macroeconomic indicators, the variation remains smaller than 0.2% in 2040 (Figure 7.7). The main effect is seen in the slight decrease of GDP, leading to a slight drop in investment and household consumption. Government consumption remains unchanged. Employment and the net wage rate increase slightly. Overall, the macroeconomic situation remains largely unchanged.

Figure 7.7. The fiscal reform scenario is not expected to lead to large macroeconomic consequences

Copy link to Figure 7.7. The fiscal reform scenario is not expected to lead to large macroeconomic consequencesPercentage changes w.r.t. the baseline scenario

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

The overall impact on government budgets is neutral as, by design, the subsidies are financed by tax revenues. Table 7.6 shows the variations for the different items in government spending and revenues. The changes are similar to the scenario in which only subsidies were implemented, but the scenario also raises taxes on metals and non-metallic minerals. Revenues from material taxes would remain moderate compared to other sources of tax revenues, for example, labour taxation accounts for 26.6% in 2040, while indirect taxes of commodities like VAT (not presented here) account for around 50% of total tax revenues.

Table 7.6. Changes in composition of government budgets following a fiscal reform for materials

Copy link to Table 7.6. Changes in composition of government budgets following a <em>fiscal reform for materials</em>Percentage of tax revenues

|

2021 |

2040 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Baseline scenario |

Fiscal reform scenario |

||

|

Tax on labour income |

27.3% |

26.5% |

26.5% |

|

Tax on primary metals |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Subsidy on recycling good use |

0.0% |

0.0% |

-0.2% |

|

Subsidy on secondary metals production |

-0.4% |

-0.4% |

-0.7% |

|

Tax on primary metals production |

0.7% |

0.7% |

0.6% |

|

Metals tax |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

|

Non-metallic minerals tax |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.2% |

|

Total taxes |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

Note: Negative values correspond to subsidies.

Source: OECD ENV-Linkages model.

7.5. Conclusions from the modelling results and next chapters

Copy link to 7.5. Conclusions from the modelling results and next chaptersOverall, the results of the simulation suggest that stand-alone subsidies to promote the use of secondary materials may only marginally improve environmental outcomes. Policies that promote secondary materials in production (i.e. closing resource loops, see also Chapter 1) would only lead to environmental benefits if secondary materials have a much smaller environmental footprint than primary materials. Furthermore, the environmental benefits of a fiscal reform for materials come mainly from the premise of displacing virgin production. Although promoting secondary materials is an important part of the policy mix in accelerating the transition to a circular economy, measures are also needed to discourage primary material extraction and use to enable changes in production and consumption patterns that lead to higher material productivity or higher asset utilisation (i.e. narrowing resource flows).7 Taxation can counter potential rebound effects on material consumption or undesired material substitution and, simultaneously, generate stronger price signals to reduce virgin materials use. When such taxes are combined with subsidies, aimed at increasing the supply and quality of secondary materials, the overall policy mix can amplify GHG emissions savings.

Overall, a policy mix comprising taxes and subsidies can help to safeguard public revenues, generate budget resources for targeted support measures, and help achieve environmental policy objectives. Such a policy mix would need to be carefully calibrated for each of the targeted materials and goals. Subsidies or fiscal incentives should be designed so as to target specific barriers that would not be overcome by pricing alone, such as a lack of awareness of opportunities in R&D and innovation for circularity, or possibly to generate political support for larger reforms. Where possible, policies should be based on life cycle metrics to ensure that shifts in production processes reduce overall environmental impacts.

The following chapters present key considerations to guide policy makers in the development of selected policy instruments to support the demand and supply of secondary materials.

Chapter 8 provides practical guidance on the introduction of virgin material taxation on construction aggregates, a relatively well-known instrument already in place in selected OECD countries and recommended for introduction following the stocktaking exercise presented in Part I.

Chapter 9 explores the potential of reduced VAT rates to support secondary materials.

Chapter 10 looks at opportunities to strengthen the use of corporate tax credits, a type of corporate income taxation incentive currently used in Italy to support preferred materials in production.

References

[9] Bibas, R., J. Château and E. Lanzi (2021), “Policy scenarios for a transition to a more resource efficient and circular economy”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 169, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1f3c8d0-en.

[10] Chateau, J., R. Bibas and E. Lanzi (2018), “Impacts of Green Growth Policies on Labour Markets and Wage Income Distribution: A General Equilibrium Application to Climate and Energy Policies”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 137, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ea3696f4-en.

[4] European Environmental Agency (2022), The role of (environmental) taxation in supporting sustainability transitions, https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/the-role-of-environmental-taxation (accessed on 4 April 2024).

[2] IEEP (2014), Environmental Tax Reform in Europe: Opportunities for the future.

[5] ISTAT (2022), “Gettito delle imposte ambientali”, I.Stat, http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCCN_IMPAMB1 (accessed on 7 September 2022).

[8] MASE - OECD (2021), An Action Plan for Environmental Fiscal Reform in Italy.

[7] MASE - OECD (2021), Opportunities and challenges of Environmental Fiscal Reform in Italy.

[1] OECD (2017), Environmental Fiscal Reform: Progress, Prospects and Pitfalls, OECD Report for the G7 Environment Ministers, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/environmental-fiscal-reform-progress-prospects-and-pitfalls.htm.

[3] World Bank Group (2022), Green Fiscal Reforms: Part Two of Strengthening Inclusion and Facilitating the Green Transition, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/dd039c18cba523a1d7f09a61e64a42fa-0080012022/original/EURER7-GFR-web-version.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2024).

[6] Zatti, A. (2017), “Verso una riallocazione verde dei bilanci pubblici”, Pavia University Press, Vol. IX, p. 168, http://archivio.paviauniversitypress.it/oa/9788869520570.pdf.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. The full list of options considered for further analysis is contained in Annex A.

← 2. The report carries out policy scenario analysis to 2040 because multiple national strategies currently implemented or planned contain targets to 2040 at the latest. For instance, the Italian National Strategy for the Circular Economy includes actions planned by 2035.

← 3. A tax on non-metallic minerals was also modelled to support the ex-ante evaluation of virgin material taxation on construction aggregates, the results of which are presented in Chapter 8.

← 4. The main limitation is that secondary materials are not readily available. Results presented here are for metals, which tend to have high recycling rates and are used in very different products, but other materials face such issues as quality and insufficient supply, as well as more complex recycling and reprocessing operations.

← 5. The instruments are introduced in the model at the global level to mitigate trade implications, which would be outside the scope of the current analysis. Annex B provides further details on how the tax levels were set.

← 6. Previous OECD work by Chateau, Bibas and Lanzi (2018[10]) suggests that environmental policies generate structural adjustment pressures on goods and labour markets through four main channels as a result of changes in: i) production modes; ii) demand patterns; iii) macroeconomic conditions; and iv) trade-specialization and competitiveness.

← 7. Reductions in demand for virgin materials can occur in all three of the main mechanisms discussed in Chapter 1, including a slowing down of resource use. The policy simulations presented in this chapter solely focus on closing the resource loop and narrowing the resource flow. Modelling non-market policies aimed at slowing the resource loop is difficult in a CGE setting due to the lack of sufficient data on their costs and impacts. Nevertheless, policies to slow down resource use, for instance, through improved eco-design for durability and repairability, form a critical component of a comprehensive policy mix for the transition to a circular economy.