This chapter introduces the context and provides an overview of the objectives and structure of the report. It outlines the key findings and conclusions derived from the analysis on opportunities to reform and enhance the use of economics instruments to support the circular economy in Italy.

Economic Instruments for the Circular Economy in Italy

1. Overview and key messages

Copy link to 1. Overview and key messagesAbstract

1.1. Introduction

Copy link to 1.1. IntroductionThe circular economy has gained increased prominence as a lever to achieve the goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Global consumption of raw materials has been steadily rising in recent decades and is projected to double (from 89 to 167 Gigatonnes) by 2060 under a business-as-usual scenario (OECD, 2019[1]). The escalating level of materials extraction, their processing, use and disposal, is a major contributor to emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) and air pollutants, the loss of ecosystem services, as well as the adverse consequences for human health, well-being and the economy. Transitioning from linear to circular economies (see Box 1.1 for a definition), which retain the value of material resources for longer, could substantially mitigate these pressures and contribute to the preservation of natural resources and the reduction of GHG emissions and air pollution.

The transition to a circular economy can yield environmental, economic and social gains, and support the shift to a low-carbon and nature positive economy. Materials management activities (i.e. those associated with the production, consumption and end-of-life treatment of physical goods in the economy)1 are linked to more than half of national GHG emissions in OECD countries (OECD, 2012[2]) and are projected to account for two-thirds of global GHG emissions in 2060 (OECD, 2019[1]). The modelling of combined energy and material transitions shows substantial synergies, including in facilitating the shift from primary to secondary materials and extending it to the energy sectors (from fossil fuels to renewables), resulting in the largest gains in materials use and value retention (Bibas, Chateau and Lanzi, 2021[3]). In addition to reduced environmental pressures, transitioning to a circular economy can support economic expansion and job creation, while lowering the risk of shocks in the supply of raw materials. Businesses will play a pivotal role in leading the transition to sustainable and circular economies, as a new policy environment provides them with unprecedented opportunities to improve human well-being and unlock positive contributions for nature and society.

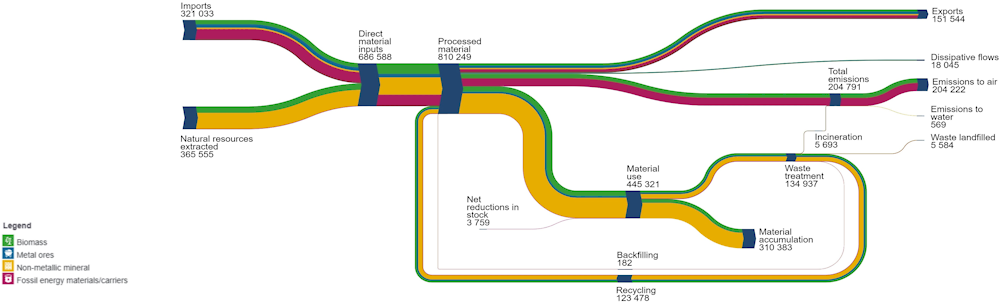

Italy is one of the European Union (EU) countries leading the circular transition. Figure 1.1 illustrates material flows in Italy for the year 2022. The main materials extracted in Italy are non-energy minerals (non-metallic minerals in particular) and biomass, while Italy’s economic system is dependent on foreign markets for energy and metal ore resources. The Italian industrial sector has historically developed high efficiency in the use of resources and methods for material recovery, also due to its limited natural resources and reliance on imports. Currently, the country performs better than the OECD average in terms of domestic material consumption (at 8.6 tonnes per capita in 2021, considerably below the OECD average of 17.5 tonnes per capita). The country’s circular material use rate is now the fourth highest in Europe: in 2022, 19% of overall materials used were recycled and fed back into the economy, compared to a EU 27 average of 12%.

Figure 1.1. Material flow diagram for Italy

Copy link to Figure 1.1. Material flow diagram for ItalyThousand tonnes, 2022

Box 1.1. Definition of the circular economy

Copy link to Box 1.1. Definition of the circular economyThe concept of the circular economy may differ across countries, with variations in the scope of policies and sectors and in the policy objectives. The OECD (Forthcoming[5]) has developed a hierarchy of definitions1 for the circular economy, as an economy in which:

the value of materials in the economy is maximised and maintained for as long as possible

the input of materials and their consumption is minimised

waste generation is prevented and negative environmental impacts reduced throughout the life cycle of materials.

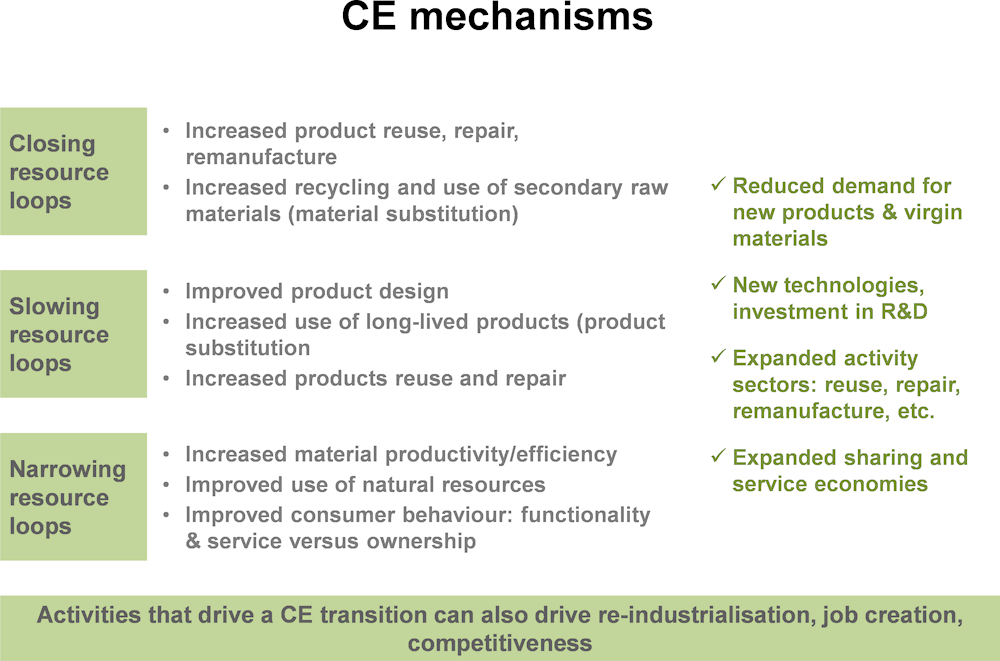

Table 1.1. Mechanisms that contribute to a circular economy

Copy link to Table 1.1. Mechanisms that contribute to a circular economyThe OECD distinguishes several mechanisms that contribute to a circular economy to varying degrees. A first, well-known mechanism is the closing of resource loops, i.e. substituting virgin materials and new products with secondary raw materials and second-hand, repaired or remanufactured products. A second, broader mechanism is the slowing of resource loops, that seeks to slow down consumption and demand for virgin materials by extending the life of existing goods, usually thanks to more durable product design. A third mechanism involves narrowing resource flows to increase resource efficiency (by decreasing the total amount of resources used per unit of output or by making better economic use of existing capacity) and to achieve a more efficient use of natural resources, materials and products (through the development and diffusion of new production technologies, better utilisation of assets, or shifts in consumption behaviour away from material intensive goods and services).

1. This hierarchy comprises a headline definition, which is accompanied by simple explanatory notes and references to the mechanisms and strategies underlying a circular economy, as well as details to guide statistical measurement.

Source: (OECD, Forthcoming[5])

Nevertheless, the full potential of the circular economy is yet to materialise. Modelling carried out with the OECD Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) ENV-Linkages model shows that, under business as usual, projected demographic and economic factors in Italy are expected to lead to a stabilisation around current levels of material consumption, which are not aligned with the sustainable future envisioned by the European Green Deal and national policy goals. The scarcity of raw materials and supply-chain disruptions, which occurred in the early phase of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, shed light on the persistent linearity of the Italian economy.

Italy’s National Strategy for the Circular Economy (“Strategia Nazionale per l’Economia Circolare”), adopted in June 2022, recognises the need for urgent action to place the country on a path towards a sustainable and circular economy and to unlock the environmental and climate benefits of the transition. Moreover, the strategy recognises the potential of the circular economy transition to contribute to the policy objectives of securing the supply of raw materials, domestic competitiveness and job creation. Bolstering markets for secondary raw materials, improving eco-design and extending the lifetime of products are among the key objectives outlined in the strategy.

The roadmap for the implementation of the Strategy for the Circular Economy (“Cronoprogramma di attuazione delle misure della Strategia Nazionale per l’Economia Circolare”) envisions action on the following key topics:

Governance of the strategy, including establishing an Observatory on the implementation of the strategy and annual reporting.

A new system of waste traceability.

Fiscal incentives to support recycling and secondary raw materials, including proposals for renewed corporate tax credits in support of secondary materials.

Reform of environmental taxation to promote recycling, including the reform and elimination of relevant environmentally harmful subsidies, measures to support municipalities and regions in waste prevention, reuse and waste sorting, and a possible reform of the landfill tax.

Right to reuse and repair, including more support offered to reuse centres and promoting reuse through public procurement approaches.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes, including the introduction of a specific supervisory body and the full implementation of an EPR scheme for textiles.

Updates to existing legislation in support of the circular economy, including national and regional waste legislation, the development and revision of mandatory minimum environmental criteria in public procurement, and end-of-waste legislation.

Support to industrial symbiosis projects, including financial support to flagship projects.

Measures on land use, including remediation and lowering the demand for more land, as well as measures on water, including for waste reuse and reducing consumption.

1.2. Purpose of this report

Copy link to 1.2. Purpose of this reportThis report explores opportunities for the reform or the introduction of selected economic instruments to advance the circular economy transition in Italy. Across multiple themes, the Strategy for the Circular Economy, and its roadmap for implementation, emphasises the potential to leverage economic instruments to align price signals with policy objectives. The use of economic instruments for environmental policy has received significant attention in the international and national policy debate in recent decades. By favouring practices that are more sustainable and circular, and penalising those that are more wasteful and harmful to the environment and human health, economic (or market-based) instruments can help to reorient consumer choices and market forces, lowering environmental impacts, while avoiding excessive economic impacts. Furthermore, environmental taxes (a subset of economic instruments) may generate revenues for public budgets and prompt incentives for green innovation at every stage of the value chain.

Italy’s current policy and legislative landscape already includes various economic instruments for the circular economy, such as landfill taxes, pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) household waste tax schemes, fees on extractive activities, EPR schemes and Green Public Procurement (GPP). However, there is still significant room for improvement to leverage their use to align price signals with negative externalities. Indeed, there are opportunities to overcome persistent obstacles in their uptake, especially across regions, and to enhance their effectiveness in delivering the expected environmental outcomes (over revenue-raising), as well as to advance an innovative use of economic instruments and introduce additional fiscal incentives to support circularity.

This report aims to support Italy’s ongoing efforts by providing policy analysis and recommendations on the role of economic instruments to promote the circular economy. The report consists of two parts.

1. Part I reviews the current policy landscape and identifies gaps and opportunities to improve the use of economic instruments for the circular economy in Italy.

2. Part II delves into a more thorough analysis of selected economic instruments. After consultation with the Italian Ministry of Environment and Energy Security (MASE), it was decided to focus the analysis on three instruments that could support markets for secondary materials: virgin material taxation on construction aggregates, reduced VAT rates on products with recycled content, and corporate income taxation (CIT) incentives in the form of tax credits.

The report is situated in the context of the project “Advanced policy instruments to accelerate the circular economy”, as part of a long-standing collaboration with the Directorate-General for Structural Reform Support (DG REFORM) of the European Commission on country-specific policy reform projects. The reform of economic instruments has long been part of domestic policy discussions in Italy. A previous project, also funded by the European Commission, administered by DG REFORM and carried out in collaboration with the Italian Government, supported the development of a national policy agenda and action plan for environmental fiscal reform in Italy. Previous projects also supported the development of an action plan for policy coherence for sustainable development.

The rest of this chapter summarises key findings from the report.

1.3. Assessment of the current policy landscape and opportunities to improve the use of economic instruments for the circular economy (Part I)

Copy link to 1.3. Assessment of the current policy landscape and opportunities to improve the use of economic instruments for the circular economy (Part I)Part I of this report identifies the potential to amplify the use of price-based economic instruments to internalise negative externalities and strengthen incentives to align the behaviour of consumers and firms with higher sustainability and circularity. Upstream in the value chain, the environmental and social impacts of virgin material extraction and use are typically not factored into their price. Hence, the prices of newly manufactured goods made from virgin materials are often more competitive than more sustainable alternatives. At the level of consumption and waste generation, there are also limited incentives to favour options higher up in the value chain, including reuse and waste prevention as well as recycling over landfilling and waste-to-energy. Multiple options are available to policy makers to update the use of economic instruments, including reforms targeted to individual instruments, the removal of environmentally harmful subsidies, and implementation as part of broader environmental fiscal reforms. As detailed in Chapters 5 and 6, the following opportunities for instrument reform and introduction were identified and could be considered:

1. Explore the relevance of a virgin material taxation applied to construction aggregates to strengthen price signals against primary materials demand. Existing fees on extractive activities are not designed to provide price signals that would affect the quantities extracted nor incentivise the use of secondary materials. The relevance of virgin material taxation could also be relevant for material groups such as plastics, i.e. through the implementation of the plastics tax to further promote circularity in the plastic packaging sector.

2. Prioritise a reform of the landfill tax characterised by a strong co-ordination between the national and regional level to harmonise and increase landfill tax rates across the country. In most regions, landfill taxes are significantly below the European average and are likely too low to discourage landfilling. A reform of the instrument at the national level is required to progressively increase regional tax rates.

3. Continue to work on reforms to remove identified environmentally harmful subsidies applying to waste disposal operations and consider the introduction of an incineration tax. This would maximise incentives for waste prevention and treatment options that sit higher in the waste hierarchy, and prevent potential lock-in effects in the long term.

4. Continue to enhance the implementation of PAYT systems by which households are charged based on the amount of mixed waste they generate. Extending the coverage of PAYT in all regions could further reduce household residual waste, thereby reducing local waste management costs. Examples of supporting measures include obligations and incentives contained in regional waste management plans (“Piani Regionali di Gestione dei Rifiuti”), the enhanced technical and financial support to municipalities, as well as information and behavioural measures targeted to households.

5. Widen support for reuse and repair to render waste prevention more convenient. In the context of EPR schemes, there are opportunities to engage Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs) in the promotion of repair and reuse practices by allowing them to count these activities towards their targets, which have so far focused on recycling. In addition, Italy could evaluate the relevance of fiscal incentives to promote repair and the sale of refurbished, remanufactured and second-hand products.

6. Continue to raise the ambition of public procurement approaches to promote circularity and green innovation even more. Since 2016, all public entities in Italy are obliged to apply minimum environmental criteria (“Criteri Ambientali Minimi”, CAM), which so far have been defined for 20 categories of goods and services. Public procurement already promotes circular practices, e.g. through recycled content requirements. Innovative strategies to promote circularity may involve a needs assessment, a focus on services and new business models (rather than products), and the adoption of contractual clauses and tender specifications that extend product lifespans. It might also be beneficial to strengthen strategic relationships with the business sector to raise awareness of market capacity and readiness for green innovation.

The report also identifies a number of cross-cutting factors to consider.

A mix of diverse, well-co-ordinated instruments is critical to the successful implementation of economic instruments and to achieve environmental policy objectives efficiently. Chapter 6 presents economic instruments proposed for reform or introduction in Italy and discusses the principal, related supporting measures.

Environmental taxes should generally be prioritised over ad hoc incentives through the tax code because of the clearer price signals generated and the lower administrative costs in general. Public acceptance of tax reforms could be improved by conducting adequate stakeholder consultations, committing to credible policy and predictable tax rates, implementing a gradual phasing in, and ensuring clarity on the use of revenues (especially at the sub-national level) (see Section 6.7.1).

Regular policy evaluation is critical to maintain the effectiveness of economic instruments in the long term. Better access to data on instrument uptake, environmental outcomes, and economic and administrative costs at all levels of government can improve the quality and effectiveness of interventions. The regular update of the Catalogue of Environmentally Harmful and Favourable Subsidies provides an excellent evidence base to inform reform efforts (see Section 6.7.2).

Continued improvements in multi-level governance and strengthened capacity-building can support implementation at the sub-national level. Current mechanisms can enhance co-ordination across local, regional and national levels of government for the reform and implementation of economic instruments and to help share good practices and lessons learned (see Section 6.7.3).

1.4. Deeper analysis on selected instruments to reduce primary material demand and support secondary materials (Part II)

Copy link to 1.4. Deeper analysis on selected instruments to reduce primary material demand and support secondary materials (Part II)Part II of this report develops practical guidance on the use of economic and fiscal instruments. After consultation with MASE and based on the findings of the analysis contained in Part I of this report, it was decided to focus the analysis on three instruments that could accelerate reductions in the extraction and use of virgin (primary) materials and support markets for recycled and other recovered (secondary) materials. These are virgin material taxation on construction aggregates, reduced VAT rates on products with recycled content, and corporate income tax credits for the use of recycled content.

The choice of focus is aligned with one of the priorities set out in the National Strategy for the Circular Economy, that is, to accelerate the shift away from primary materials. In recent years, Italy has introduced an increasing number of measures to support recycled and other recovered materials, such as recycled content requirements in public procurement criteria and corporate tax credits to support preferred materials. However, direct disincentives against virgin material extraction and use remain limited. As virgin material taxation on construction aggregates is a relatively well-known measure, which is already in place in some OECD countries, the analysis in this report aims to offer practical guidance for future legislative efforts in this area. At the same time, the analysis in this report also offers guidance on efforts to strengthen and extend fiscal incentives for recovered materials, as emphasised by Italy’s Strategy for the Circular Economy.

To explore the expected environmental outcomes and economic impacts of selected instruments, as well as the possible synergies across measures, simulations were performed using the OECD ENV-Linkages model. This is a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model that links detailed projections of economic activity to material demand and environmental impacts, in this case, to produce projections for Italy to 2040. It was used to model a fiscal reform scenario for materials that combines subsidies to support secondary materials and taxes on primary materials, using tax revenues to finance subsidies.

1.4.1. Virgin material taxation on construction aggregates

Copy link to 1.4.1. Virgin material taxation on construction aggregatesItaly extracts around 86 million cubic metres of virgin construction aggregates every year. The construction sector is a strategic sector for the circular transition, mainly due to its raw material demand and significant contribution to waste generation. The sector's dependency on virgin materials raises concerns over security of supply, potentially impacting the competitiveness of the Italian economy. Currently, most Italian regions impose fees on the extraction of materials, such as sand, gravel and rock, with wide differences across the national territory in the fee rates imposed. Due to their design, existing fees do not alter behaviour in terms of material extraction and sourcing.

A tax on the extraction of virgin construction aggregates could discourage primary materials extraction and encourage a shift towards secondary materials use (including from end-of-waste processes). Sub-national levels of government would be responsible for the design and implementation of a tax on construction aggregates, but an established national legislative framework would help to harmonise its implementation, while allowing regions to adapt to local circumstances.

Key guidance on the design and implementation of a virgin material tax in Italy includes:

Taxable event and tax base: it is recommended that the tax applies to the extraction of quarried non-energy minerals and that it covers all material categories.

Tax rate: ad quantum taxes are preferred and, ideally, should combine both a measure of the areas affected (e.g. extraction surface areas) and the extracted quantities (by weight or volume). In the Italian context, minimum tax rates could be established at the national level for each category of extracted materials, and be updated regularly.

Earmarking of revenues is generally not advised, although it can be helpful in specific circumstances to increase acceptance of the tax by stakeholders, in particular, by responding to concerns for competitiveness impacts for businesses or for the sake of affordability among households. Sub-national governments are best placed to allocate revenues based on local circumstances. National legislation could establish minimum requirements to be included in regional plans on extractive activities, e.g. obligations to be included in environmental permits and provisions for quarry restoration following closure, as well as provisions to support municipalities affected by the quarrying activities.

The estimated economic and environmental outcomes of the proposed tax on the extracted construction aggregates appear relatively modest due to the generally low demand elasticity. This will likely have a modest impact both in terms of costs (to those subject to the tax) and in terms of environmental benefits. Evidence from international experience suggests that virgin material taxes on construction aggregates are most effective when implemented alongside other policies aimed at increasing the demand for and supply of recycled materials to provide alternatives to the use of virgin materials (e.g. landfill taxes, minimum recycled content requirements, support for selective demolition and improved quality standards for construction and demolition waste (CDW), end-of-waste criteria for CDW and classification of industrial by-products) and enhanced monitoring of waste and control systems.

1.4.2. Fiscal incentives to promote secondary materials

Copy link to 1.4.2. Fiscal incentives to promote secondary materialsA large number of policy instruments are available to support demand for secondary materials, including both direct regulation and indirect recycled content requirements. Italy has introduced minimum recycled content requirements for several product groups and materials. They primarily employ indirect approaches through public procurement (e.g. CAM for public construction works, award criteria for textile products) and corporate tax credits to support recycled content (and compostable materials) in products and packaging. MASE expressed a particular interest in practical guidance on two instruments: reduced VAT rates on products with recycled content (for its potential introduction nationally) and corporate tax credits (to strengthen recently introduced measures).

Reduced VAT rates

Copy link to Reduced VAT ratesA value added tax (VAT) is a broad-based tax levied on the final consumption of goods and services by households. Most EU Member States apply one or two reduced rates (five Member States also apply a super-reduced rate) generally to alleviate the potentially regressive nature of consumption taxes and to encourage the consumption of goods and services that bear positive externalities, or to boost selected economic sectors. Insights from empirical evidence suggest that reduced VAT rates are generally an inefficient means to achieve these policy objectives as they may face issues of limited pass-through to prices or windfall gains. They may also increase administrative and compliance costs, distort household spending patterns, as well as result in distributional impacts on households. Tax policy tends to favour a uniform VAT rate to ensure stable revenues and enhance economic efficiency.

In Italy, VAT revenues represent 24% of general government revenues and 6.8% of Italy’s gross domestic product (GDP). The standard rate is set at 22%, with two reduced rates of 10% and 5% that apply to a range of goods and services, as well as a super-reduced rate of 4% applied to a list of essential goods. Currently, the VAT system is being revised to align with recent changes made to the EU VAT Directive aimed at harmonising rules across the European Union, but also to restrict the introduction of additional preferential VAT rates.

Tax relief applied on products with recycled content could hypothetically be applied by dropping the standard rate (22%) to the reduced rate of 10%. The preferential VAT rate could lower their prices relative to products that do not contain recycled content. A shift in consumer preferences, influenced by lower prices, could increase demand for recycled materials higher up in the value chain and potentially reduce the use of virgin materials.

This report highlights several challenges and uncertainties that could diminish the effectiveness of reduced VAT rates in achieving the sought-after environmental outcomes, as highlighted below.

Legal and implementation challenges. Consideration of this measure would require legislative changes and tools to support implementation. Currently, products containing recycled content are not listed in the categories of products eligible for reduced VAT rates in Annex III of the EU VAT Directive. Differences in VAT rates between similar products may give rise to administrative and legal conflicts about the classification of specific goods. There could also be practical difficulties as regards identifying the eligible products, as information and certification schemes for recycled content are not available for most products and materials.

Uncertainty about environmental outcomes. As evidenced by scenario simulations performed with the OECD’s ENV-Linkages model (see Chapter 7), introducing stand-alone measures to support secondary materials could effectively support a shift from primary to secondary materials, but it could also result in considerable rebound effects on consumption, potentially worsening environmental outcomes compared to not introducing the measures. Secondly, empirical evidence suggests a limited effectiveness of reduced VAT rates in changing consumption patterns. This may be because retailers could pocket a share of the VAT reduction or because the reduction in the product price is so negligible that it does not provide an incentive. As the tax relief only applies to finished products, it is uncertain to what extent the measure would generate changes in behaviour upstream in the value chain or a reduction in the use of virgin materials.

Fiscal impacts and the efficient use of resources. Reduced VAT rates could result in significant losses in fiscal revenue. For instance, a reduced VAT rate on textile products with recycled content could lead to losses in public revenues of EUR 520-769 million in the first year of implementation alone (corresponding to 0.4-0.6% of total VAT revenues in 2022). While short-term revenue losses may be justified by the long-term benefits for the environment and economic growth, it remains uncertain whether VAT reductions can offer benefits compared to alternative instruments, such as targeted direct subsidies for the production of secondary materials. New reduced VAT rates may add to the complexity of the VAT system, increasing the costs of monitoring and compliance, and creating greater incentives for misclassification and non-compliance. Furthermore, there are also important distributional concerns associated with the introduction of reduced VAT rates, as high-and low-income households display very different expenditure patterns.

Overall, the introduction of reduced VAT rates would need to be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis. The extent of environmental benefits expected from this measure could differ greatly depending on the product groups to which it is applied and the targeted materials. Product groups such as textiles, for which certification schemes for recycled content are already in place, would be better suited to early introduction compared to those without certification schemes.

The modelling performed suggests that the combination of incentive measures for recycled materials with parallel taxation of primary materials is generally preferred to amplify the benefits of the policies and achieve budget neutrality. The promise of environmental benefits from higher circularity rests on the assumption that demand for primary materials is reduced, for instance, because they are displaced by secondary materials or because of improved resource efficiency in the production processes. Taxation can counter potential rebound effects on consumption associated with subsidies (or tax incentives) or the unintended consequences linked to material substitution, thereby generating stronger price signals to reduce virgin materials use. By using tax revenues to finance subsidies, for instance, targeted at increasing the supply and quality of secondary materials, the overall policy mix may achieve a bigger impact on GHG emissions, as well as other environmental impacts. Other ways of achieving budget neutrality include increases in other environmental taxes or the reform and removal of preferential VAT rates that have been classified as environmentally harmful.

Corporate Income Tax (CIT) incentives in the form of tax credits

Copy link to Corporate Income Tax (CIT) incentives in the form of tax creditsOver the last 5 years, Italy has increased the number of fiscal incentives to promote circularity-aligned behaviours among firms, including through i) corporate tax credits that apply to the purchase of products made from recycled plastics, biodegradable and compostable packaging or packaging containing recycled paper, plastics or aluminium, and ii) corporate tax credits for the purchase of intermediary and final products composed of materials from the recycling of waste or of scrap materials, and high-quality compost. The available information indicates a high uptake for the first measure among firms, which led to a renewal for 2023/2024. Conversely, the second measure was less popular, possibly due to the small size of the incentive and the difficulty of meeting the requirements (the measure was not renewed). However, the short implementation period of these measures prevents a thorough assessment at this time.

Sustaining measures over multiple years could increase the impact of tax incentives, though this would come at additional fiscal costs. Ensuring the timely implementation and consistency of corporate tax credits would help send clear price signals and provide better long-term visibility to economic actors, allowing firms to factor them into their long-term investment plans. This is particularly relevant for incentives that aim to structurally modify a firm’s production processes over the long term. Longer implementation periods would also enhance data availability and opportunities for adequate ex-post evaluation and the eventual reform of introduced measures.

The design of the measures is key to delivering environmental outcomes efficiently and ensuring additionality of the measure (i.e. that additional investments are achieved, above the level of investments reached without the incentive), as well as limiting the fiscal costs. Specifically, the instrument design involves such strategic choices as eligibility requirements (i.e. the recycled content threshold) and the size of the incentive. Market studies and industry consultations could help calibrate both decisions in a way that generates meaningful price signals to elicit behavioural changes by firms, while also minimising risks of unintended effects associated with supply chain disruptions or material substitutions. A progressive tightening of recycled content thresholds may help to ensure that these continue to provide meaningful incentives in the long run, in line with long-term policy ambitions expressed in the National Strategy for the Circular Economy. Overall, a clear objective, careful targeting, clear eligibility, systematic ex-post monitoring and evaluation are all critical components for the successful use of corporate tax credits.

Nevertheless, there are uncertainties as to whether corporate tax credits (and tax incentives in general) offer a cost-effective means to stimulate desired changes in firm behaviour and achieve environmental gains, over alternative policy instruments. The literature suggests that expenditure-based CIT incentives may effectively stimulate R&D investments by firms, however the rationale for their use in support of environmental policy objectives is less clear and ascertaining positive environmental impacts via this route is difficult. Tax incentives generally target environmental externalities poorly, and have drawbacks that include fiscal costs, risks of windfall gains and potentially substantial administrative and compliance costs. At the same time, corporate tax credits offer the advantage of being deployable and adjustable rather quickly and, in some contexts, may face fewer political economy challenges than environmental taxes.

Given the associated costs and limited empirical evidence on their effectiveness as a tool for environmental policy, corporate tax credits may be best considered as supporting measures within a broader policy mix. While pricing is, generally, to be prioritised over ad-hoc fiscal incentives, corporate tax credits can have a role to play as long as they target specific barriers not addressed by other instruments in the policy mix and enhance overall policy efficiency in the promotion of more sustainable and circular production practices. Furthermore, well-targeted tax incentives could help to generate buy-in for broader policy reforms to support the circular economy. To minimise the risks of windfall gains, corporate tax credits should be carefully designed based on a clear policy objective, closely monitored and evaluated, and eventually reformed in light of emerging empirical evidence.

Additional complementary policies could include measures aimed at increasing the availability of recovered materials from waste, such as enhanced separate waste collection, the development of domestic reprocessing capacity, and the removal of regulatory barriers, notably, to facilitate the use of by-products and other recovered materials in processes of industrial symbiosis.

References

[3] Bibas, R., J. Chateau and E. Lanzi (2021), “Policy scenarios for a transition to a more resource efficient and circular economy”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 169, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c1f3c8d0-en.

[4] Eurostat (2024), Material flow diagram, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/sankey/circular_economy/sankey.html (accessed on 30 April 2024).

[6] McCarthy, A., R. Dellink and R. Bibas (2018), “The Macroeconomics of the Circular Economy Transition: A Critical Review of Modelling Approaches”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 130, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/af983f9a-en.

[1] OECD (2019), Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307452-en.

[2] OECD (2012), Greenhouse gas emissions and the potential for mitigation from materials management within OECD countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/env/waste/50035102.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

[5] OECD (Forthcoming), Monitoring progress towards a resource efficient and circular economy.

Note

Copy link to Note← 1. Examples of categories of activities not associated with materials management include commercial energy use, residential energy use and passenger transportation (OECD, 2012[2]).