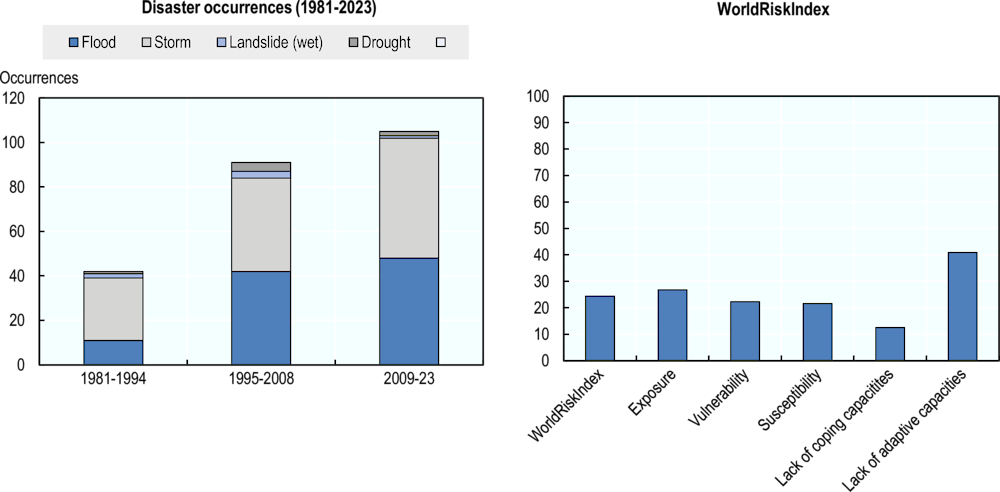

Viet Nam ranks among the most hazard-prone countries in the Asia-Pacific region. It is highly exposed to floods, cyclones and landslides, and it also faces the risk of droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis and heatwaves (Lan Huong et al., 2022[1]). The WorldRiskIndex 2023 classifies the country’s exposure as very high, as shown in the figure below. Disaster risk in Viet Nam is characterised by a high level of hazard and exposure, but relatively lower vulnerability and higher coping capacity.

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2024

Viet Nam

Introduction

Viet Nam: Disaster occurrences (from 1981 to 2023) and WorldRiskIndex

The hazardscape

Viet Nam is at risk of both riverine and coastal flooding. The central and northern hilly regions are most exposed to flash floods, and the low-lying deltas are exposed to slower-moving riverine floods and storm surges (Ba, Nam and Hung, 2022[2]; Nguyen et al., 2021[3]). Floods, which are often caused by cyclone-induced rainfall, represent the most frequent and impactful hazard in the country, accounting for most disaster damage and losses (World Bank and ADB, 2020[4]). Between 2000 and 2023, floods and storms accounted for 96% of disaster-related deaths and 66% of economic damage. Flood risk threatens more than 300 000 jobs in the agriculture, aquaculture, tourism and industry sectors (Rentschler et al., 2020[5]), and flood impacts are increasing. Between 2010 and 2030, the number of people affected by riverine flooding is projected to increase from 2.4 million to 3.8 million annually, and annual urban damage is projected to rise from USD 2.3 billion to USD 14 billion (WRI, n.d.[6]). Flood risks are exacerbated by rapid urbanisation, poor urban development planning and improper land use. Examples include loss of water retention capacity due to excessive construction of non-permeable surfaces and reductions in drainage due to ground levelling and construction in flood-prone areas (Ba, Nam and Hung, 2022[2]; Nguyen et al., 2021[3]).

Viet Nam is exposed to tropical cyclones, which occur more frequently in the central and northern regions (Takagi, 2014[7]). Between 1977 and 2017, approximately 2-3 cyclones with wind speeds above 20 knots made landfall along the country’s coastline annually during the southwest monsoon between June and November (Takagi, 2019[8]; Nguyen-Thi et al., 2012[9]). Storm-related damage has been increasing, and much of this increase appears attributable to the country’s economic development rather than significant trends in storm occurrence in the last four decades (Takagi, 2019[8]). The Red River delta, southern coastal area and southeast are at high risk due to their geophysical features and typhoon intensity. These risks could worsen due to future sea-level rise (Nguyen, Liou and Terry, 2019[10]).

Viet Nam also faces droughts, and their frequency has been increasing. Drought risk is highest during the dry season from November to March (Vu-Thanh, Ngo-Duc and Phan-Van, 2013[11]). Drought events in recent years, including severe drought and saline intrusion events in 2016 and 2019-20, affected millions of people, caused water stress to hundreds of thousands of households and severely impacted the agricultural sector by damaging crops and reducing yields (Park et al., 2021[12]; Thao et al., 2019[13]; UN Viet Nam, 2016[14]). The drought vulnerability of Vietnamese communities appears to be largely determined by water availability and livelihood strategies (Thao et al., 2019[13]). Drought-affected communities suffer adverse health impacts, with households with low agricultural incomes and a lack of coping capacity being especially vulnerable (Lohmann and Lechtenfeld, 2015[15]).

Moreover, Viet Nam faces the risk of landslides, which are typically triggered during heavy rainfall. Landslides are among the most serious hazards in the mountainous parts of central and northern Viet Nam due to the geological and topographic conditions and the occurrence of tropical storms in these regions (Le et al., 2021[16]). Human activities such as deforestation, construction and other changes to the environment exacerbate the landslide risk (Le et al., 2021[16]; Nguyen, Tien and Do, 2019[17]).

Viet Nam faces tsunami risk from earthquakes in the South China Sea, with central and north-central regions estimated to be at most exposed (Hong Nguyen et al., 2014[18]). A tsunami generated by an earthquake in the Manila Trench (the most probable tsunami source) could reach the Vietnamese coastline in approximately two hours (Hong Nguyen, Cong Bui and Dinh Nguyen, 2012[19]).

Climate change perspective

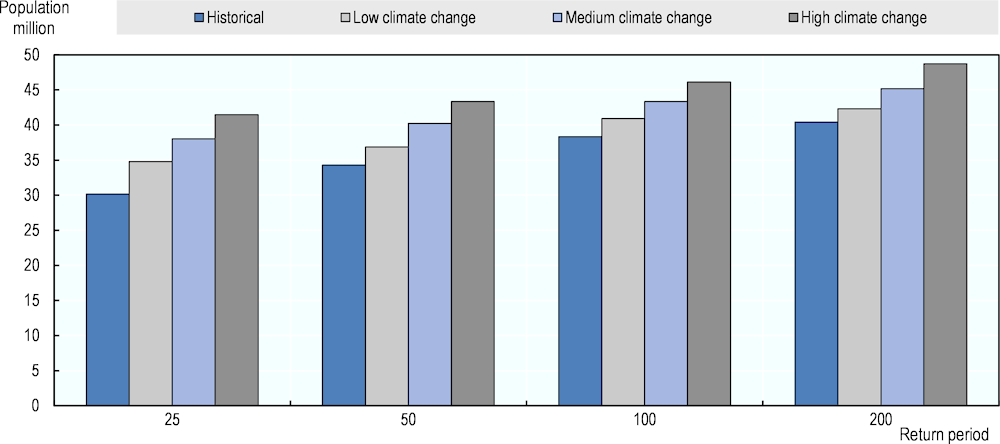

Disaster exposure in Viet Nam is significant. Approximately two-thirds of the population reside in storm- and flood-exposed locations along the coast and in low-lying deltas, and 97% of nighttime lights (a proxy for the concentration of economic activity) are located in areas exposed to floods (Chantarat and Raschky, 2020[20]). Assuming no protection, one-third of the population is exposed to a 1-in-25-year flood event (Bangalore, Smith and Veldkamp, 2018[21]). More than one-third of settlements are located on eroding coastlines, and 26% of public hospitals and health care centres, as well as 11% of schools, are at risk of severe coastal flooding (Rentschler et al., 2020[5]).

Estimated population exposed to flood risk, by scenario and return period

Source: (Bangalore, Smith and Veldkamp, 2018[21]), “Exposure to floods, climate change, and poverty in Vietnam”, Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, Vol. 3, pp. 79-99, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41885-018-0035-4.

Development activities continue to be concentrated in high-risk coastal areas, increasing the exposure of population and assets. Both exposure and vulnerability are exacerbated by development in areas that act as a natural buffer to inundation, such as floodplains, coastal swamps and drainage channels (Nguyen et al., 2021[3]). Approximately 12% of the population lives below the national poverty line, and 38% of poor households are exposed to disasters. This population is characterised by higher vulnerability and a lack of capacity to cope with disaster impacts (UNDRR, 2022[22]). Land scarcity in urban areas is forcing poor populations to occupy high-risk areas, and they reside in low-quality, non-engineered houses due to a lack of resources, contributing to their vulnerability (Bangalore, Smith and Veldkamp, 2018[21]; UNDRR, 2022[22]).

All these factors make them more exposed to climate change. Viet Nam’s disaster risk is thus being shaped by climate change and sea-level rise. These factors are expected to exacerbate the risks of flooding, drought, erosion and saline intrusion (Rentschler et al., 2020[5]). Climate change could increase population exposure to severe floods (Bangalore, Smith and Veldkamp, 2018[21]). Unless effective adaptation measures are adopted, fluvial flooding may impact an additional 3-9 million people by 2035‑44, and 6-12 million more people may be affected by coastal flooding by 2070-2100 (World Bank and ADB, 2020[4]). Storm surges may increase by up to 1 metre, and the range of the coastline currently exposed to storm surge heights of 2.5 metres will likely more than double by 2050 (Wood et al., 2023[23]). The Mekong River delta region is projected to face a 20% increase in delta inundation, prolonged submergence of 1‑2 months and a two- or three-fold increase in annual rice crop damage (Triet et al., 2020[24]). The annual probability of drought will likely increase by approximately 10% (World Bank and ADB, 2020[4]). By 2050, 39% of the country’s GPD is projected to be exposed to the physical risks of climate change, such as floods, storms, wildfires and sea-level rise (S&P, 2022[25]).

Challenges for disaster risk management policy

Viet Nam’s disaster risk management efforts would benefit from increased human and financial resources; stronger co‑operation among regions, ministries and sectors; and more granular disaster data to optimise policy for local needs (Lan Huong et al., 2022[1]).

Enhancing the funding and capacity of urban planning institutions would allow for the implementation of updated risk-informed building codes, safety standards, and enforcement of each as well as state-of-the-art spatial planning that considers disaster risk exposure in an optimal fashion. For instance, two-thirds of the country’s dike system does not meet current safety standards, and the standards leave significant protection gaps in some high-growth provinces (Rentschler et al., 2020[5]). Increasing capacity and funding within the Viet Nam Disaster and Dyke Management Authority would help upgrade substandard dikes, benefitting those dependent on their protection.

Gaps in the existing flood risk assessments include insufficient attention to social drivers of flood risk and vulnerability (Nguyen et al., 2021[3]). Urban and peri-urban areas are seeing an increase in flood risks while also experiencing high population growth yet are characterised by relatively lower flood resilience than in rural areas (FRA, 2023[26]). Therefore, these areas should be designated priority locations for disaster risk management improvement initiatives. Poverty eradication should be integrated into flood risk management as one of the main priorities, as poverty-related factors were identified to be among the root causes limiting disaster resilience of households in rural and suburban areas (Nguyen et al., 2021[27]).

Disaster risk is financed primarily from national and local contingency reserve funds, but also from sources outside the state budget such as the Fund for Natural Disaster Prevention and Control, as well as international assistance. The present financial capacity is insufficient, leaving the country at a risk of a severe financing gap, especially in the case of major events. The use of ex-ante funding mechanisms such as disaster insurance is currently limited. Disaster insurance is sold as an add-on to existing policies and has very low penetration rates. Public assets are insured for fire hazards, but insurance for flood and typhoon hazards, arguably the most pertinent risks, is almost non-existent (ISF, 2022[28]), suggesting community-level awareness of disaster risk must improve (Lan Huong et al., 2022[1]).

References

[2] Ba, L., T. Nam and L. Hung (2022), Flash Floods in Vietnam, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10532-6.

[21] Bangalore, M., A. Smith and T. Veldkamp (2018), “Exposure to Floods, Climate Change, and Poverty in Vietnam”, Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, Vol. 3/1, pp. 79-99, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-018-0035-4.

[20] Chantarat, S. and P. Raschky (2020), Natural Disaster Risk Financing and Transfer in ASEAN Countries, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.198.

[26] FRA (2023), Flood risks in urban areas: More than an act of nature, https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/flood-risks-urban-areas-more-act-nature.

[19] Hong Nguyen, P., Q. Cong Bui and X. Dinh Nguyen (2012), “Investigation of earthquake tsunami sources, capable of affecting Vietnamese coast”, Natural Hazards, Vol. 64/1, pp. 311-327, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-012-0240-3.

[18] Hong Nguyen, P. et al. (2014), “Scenario-based tsunami hazard assessment for the coast of Vietnam from the Manila Trench source”, Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, Vol. 236, pp. 95-108, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pepi.2014.07.003.

[28] ISF (2022), Disaster Risk Transfer Solutions for Urban Settings in Vietnam, https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/disaster-risk-transfer-solutions-urban-settings-vietnam-0.

[1] Lan Huong, T. et al. (2022), “Disaster risk management system in Vietnam: progress and challenges”, Heliyon, Vol. 8/10, pp. e10701, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10701.

[16] Le, T. et al. (2021), “Developing a Landslide Susceptibility Map Using the Analytic Hierarchical Process in Ta Van and Hau Thao Communes, Sapa, Vietnam”, Journal of Disaster Research, Vol. 16/4, pp. 529-538, Fuji Technology Press Ltd., https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2021.p0529.

[15] Lohmann, S. and T. Lechtenfeld (2015), “The Effect of Drought on Health Outcomes and Health Expenditures in Rural Vietnam”, World Development, Vol. 72, pp. 432-448, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.003.

[27] Nguyen, C. et al. (2021), “Long-Term Improvement in Precautions for Flood Risk Mitigation: A Case Study in the Low-Lying Area of Central Vietnam”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, Vol. 12/2, pp. 250-266, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-020-00326-2.

[10] Nguyen, K., Y. Liou and J. Terry (2019), “Vulnerability of Vietnam to typhoons: A spatial assessment based on hazards, exposure and adaptive capacity”, Science of The Total Environment, Vol. 682, pp. 31-46, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.069.

[17] Nguyen, L., P. Tien and T. Do (2019), “Deep-seated rainfall-induced landslides on a new expressway: a case study in Vietnam”, Landslides, Vol. 17/2, pp. 395-407, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01293-6.

[3] Nguyen, M. et al. (2021), “Understanding and assessing flood risk in Vietnam: Current status, persisting gaps, and future directions”, Journal of Flood Risk Management, Vol. 14/2, Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12689.

[9] Nguyen-Thi, H. et al. (2012), “A Climatological Study of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in Vietnam”, SOLA, Vol. 8/0, pp. 41-44, Meteorological Society of Japan, https://doi.org/10.2151/sola.2012-011.

[12] Park, E. et al. (2021), “The worst 2020 saline water intrusion disaster of the past century in the Mekong Delta: Impacts, causes, and management implications”, Ambio, Vol. 51/3, pp. 691-699, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01577-z.

[5] Rentschler, J. et al. (2020), Resilient Shores: Vietnam’s Coastal Development Between Opportunity and Disaster Risk, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34639.

[25] S&P (2022), Weather warning: Assessing countries’ vulnerability to economic losses from physical climate risks, https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/ratings/research/101529900.pdf.

[8] Takagi, H. (2019), “Statistics on typhoon landfalls in Vietnam: Can recent increases in economic damage be attributed to storm trends?”, Urban Climate, Vol. 30, pp. 100506, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100506.

[7] Takagi, H. (2014), “Tropical cyclones and storm surges in southern Vietnam”, Coastal Disasters and Climate Change in Viet Nam, pp. 3-16, Elsevier, https://waseda.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/tropical-cyclones-and-storm-surges-in-southern-vietnam.

[13] Thao, N. et al. (2019), “Assessment of Livelihood Vulnerability to Drought: A Case Study in Dak Nong Province, Vietnam”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, Vol. 10/4, pp. 604-615, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-019-00230-4.

[24] Triet, N. et al. (2020), “Future projections of flood dynamics in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta”, Science of The Total Environment, Vol. 742, pp. 140596, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140596.

[14] UN Viet Nam (2016), Viet Nam: Drought and saltwater intrusion situation update no. 4, https://m.reliefweb.int/report/1604881/viet-nam/viet-nam-drought-and-saltwater-intrusion-situation-update-no-4-11-july-2016?lang=fr.

[22] UNDRR (2022), Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2022: Our World at Risk: Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future, https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2022-our-world-risk-gar#container-downloads.

[11] Vu-Thanh, H., T. Ngo-Duc and T. Phan-Van (2013), “Evolution of meteorological drought characteristics in Vietnam during the 1961–2007 period”, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, Vol. 118/3, pp. 367-375, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-013-1073-z.

[23] Wood, M. et al. (2023), “Climate-induced storminess forces major increases in future storm surge hazard in the South China Sea region”, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, Vol. 23/7, pp. 2475-2504, Copernicus GmbH, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-23-2475-2023.

[4] World Bank and ADB (2020), Climate Risk Country Profile: Viet Nam, https://www.adb.org/publications/climate-risk-country-profile-viet-nam/.

[6] WRI (n.d.), AQUEDUCT Global Flood Analyzer, https://floods.wri.org/#.