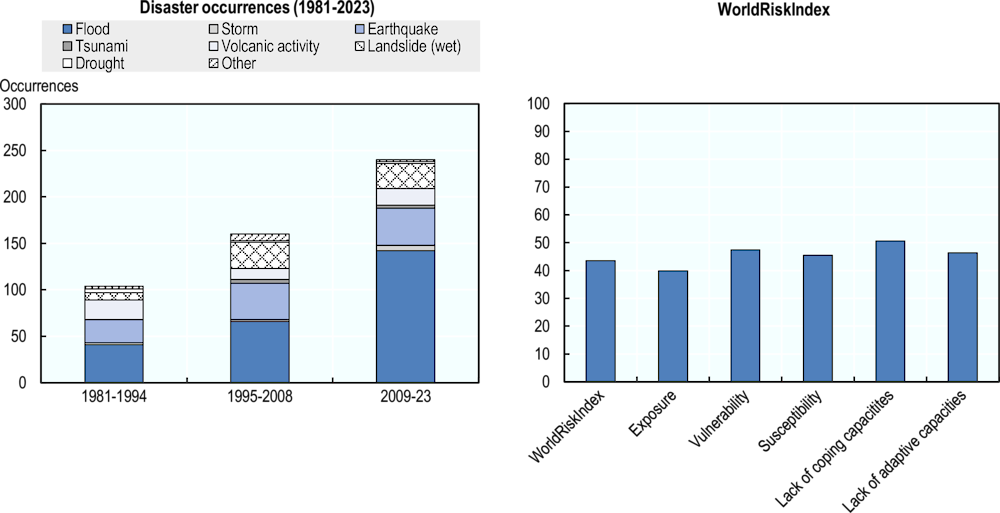

Indonesia is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, characterised by high levels of natural hazards along with high vulnerability and exposure. It is classified as facing a very high disaster risk, ranking second in the WorldRiskIndex 2023. Between 2000 and 2022, disasters triggered by natural hazards caused almost 190 000 deaths and affected nearly 24 million other people (CRED, 2024[1]).

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2024

Indonesia

Introduction

Indonesia: Disaster occurrences (from 1981 to 2023) and WorldRiskIndex

The hazardscape

Indonesia is exposed to a wider range of natural hazards than the countries in peninsular Southeast Asia. These hazards include both hydrometeorological events (floods, droughts, cyclones and heatwaves) and geophysical hazards (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and landslides). While most of the disaster events are hydrometeorological , and they affect the greatest number of people on average, the geophysical hazards can be more deadly and cause greater damage to property and infrastructure (Djalante et al., 2017[2]).

Indonesia experiences both riverine and coastal flooding, and both their impact and frequency is increasing. The number of people affected by riverine flooding annually is projected to grow from 6 million to almost 9 million between 2010 and 2030 (WRI, n.d.[3]). La Niña conditions (part of the El Niño Southern Oscillation [ENSO] cycle) can significantly increase the rainfall amounts in some years, exacerbating the risk of inland flooding. Indonesia is also impacted by the risks posed by cyclones from both the southeastern Indian Ocean (between January and April) and the western Pacific (between May and December). Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of these hydrometeorological hazards (World Bank and ADB, 2021[4]). The mega-city of Jakarta is particularly exposed given its low-lying location and rising sea levels.

Parts of the country regularly experience drought conditions as well, with the islands of Java, Bali and Nusa Tenggara estimated to be the most exposed and vulnerable to extreme drought impacts, especially in El Niño years. For example, the drought of 2015 affected over 82 000 hectares of paddy fields in Central Java (Pratiwi et al., 2020[5]).

Landslides in Indonesia are often caused by high rainfall or earthquakes and constitute a significant risk, accounting for a substantial fraction of disaster-related deaths in the country (Cepeda et al., 2010[6]; Rahardjo and Marhaento, 2018[7]). Between 1995 and 2005, landslides in Java caused more than 1 100 deaths (Zamroni, Kurniati and Prasetya, 2020[8]). The 2018 Lombok earthquake sequence alone triggered more than 10 000 landslides (Zhao, Liao and Su, 2021[9]).

Indonesia’s location along the Pacific Ring of Fire, at the intersection of three tectonic plates, makes it highly exposed to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis (Jufriansah et al., 2021[10]). Earthquakes of magnitude 6.0 and higher occur once a year on average and are associated with significant damages. Between 2000 and 2022, the country reported 74 damaging earthquakes, which caused estimated damage and losses of more than USD 13.5 billion (CRED, 2024[1]).

Tsunamis represent another major hazard, especially given their possible high-mortality consequences. Between 1900 and 2020, Indonesia experienced more tsunamis than any other country (Reid and Mooney, 2022[11]). In any given year, the regions of Sumatra, Java, Bali, Lombok and Papua, face a 1-10% chance of experiencing a tsunami of over 3 metres high, which could cause severe inundation and fatalities (Horspool et al., 2014[12]). The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was the deadliest on record, causing approximately 230 000 deaths globally. Seventy-three percent of these deaths occurred in Indonesia (in Sumatra), which also faced damage estimated at USD 4.45 billion (Ministry of National Development, 2005[13]). Tsunami risk is increasing due to growing population density in coastal regions (Løvholt et al., 2014[14]; Reid and Mooney, 2022[11]). Mortality may have been reduced in more recent tsunami events through the implementation of early warning systems, enabling timely evacuations (Horspool et al., 2014[12]), but the system of early warnings is yet to be tested fully.

Volcanic eruptions constitute another hazard. Indonesia is home to more than 100 active volcanoes and records at least one significant eruption annually. While active volcanoes are often located in remote areas and most eruptions do not result in significant damage, some have led and may lead to severe impacts, including the generation of tsunamis. Between 2006 and 2020 on the island of Java, which has the highest population density and where the volcanic hazard is high, earthquakes and other geohazards caused 7 000 fatalities and resulted in injuries and displacement affecting 1.8 million people (Pasari et al., 2021[15]).

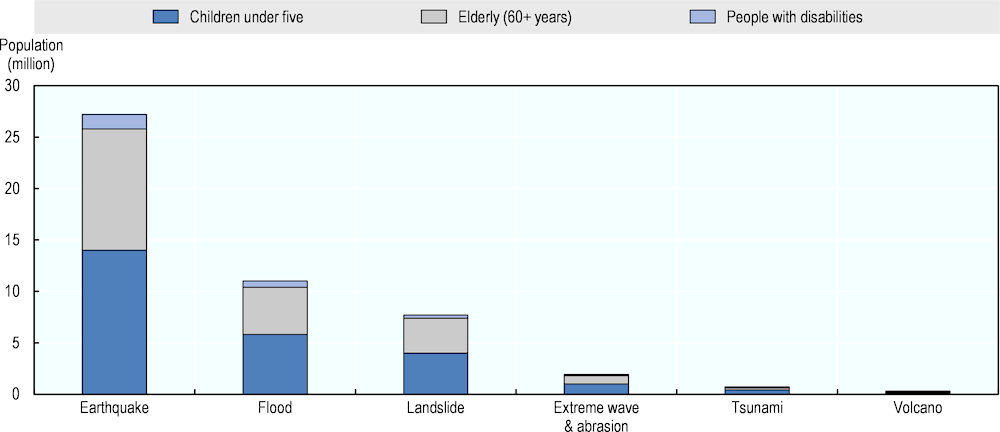

Vulnerable population of Indonesia exposed to natural hazards

Note: Vulnerable population includes children under five, people over 60 years of age, and people with disabilities.

Source: (UNFPA, 2015[16]), Population Exposed to Natural Hazards, United Nations Population Fund and Government of Indonesia, https://indonesia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Population_Exposed_0.pdf.

Climate change perspective

Indonesia is characterised by extremely high disaster exposure, with 97% of the population living in disaster-prone regions (UNFPA, 2015[16]). As of 2000, almost 40 million people (18% of the population) inhabited low elevation coastal zones, with the number projected to increase to almost 60 million by 2030 (Neumann et al., 2015[17]). More than 148 million people (62.4% of the population) are exposed to earthquakes, over 63 million to floods, and more than 40 million are exposed to landslides (UNFPA, 2015[16]). Continuous development in areas prone to landslides and floods is increasing disaster exposure (Rahardjo and Marhaento, 2018[7]).

Disaster vulnerability is exacerbated by factors such as significant poverty, poorly maintained protective infrastructure, unequal economic development and rapid urbanisation (Hodgkin, 2016[18]; Djalante et al., 2017[2]). As of 2021, 14% of the population lived below the national poverty line (UNDRR, 2022[19]). The poor condition of housing and infrastructure greatly increases disaster vulnerability (Jena, Pradhan and Beydoun, 2020[20]).

Challenges for disaster risk management policy

Disaster-related activities are governed at a national level by the Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana; BNPB). Activities at a subnational level are managed by local governments with the support of BNPB (Srikandini, Hilhorst and Voorst, 2018[21]). The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami led to a reform of Indonesia’s disaster-related laws, policies and institutions. This significantly increased its disaster risk management capabilities and shifted disaster risk management processes towards a more proactive approach (Djalante et al., 2017[2]). The recovery from the 2004 tsunami is generally considered a success, with significant progress since then at the national level. However, local governments are still viewed as lacking the financial and human resources to manage disaster risk effectively (Djalante et al., 2017[2]; Srikandini, Hilhorst and Voorst, 2018[21]). There is room for improvement in co‑ordination between the central, provincial and local governments related to response planning, and similar challenges in the co-ordination of activities with international organisations (UNDRR, 2020[22]; De Priester, 2016[23]).

The priorities for enhancing Indonesia’s disaster risk management include strengthening risk governance at the local level and improving co‑ordination between provincial and local disaster risk management actors (Djalante et al., 2017[2]; De Priester, 2016[23]; Mardiah, Lovett and Evanty, 2017[24]). Activities related to disaster management would also benefit from further technology adaptation, enhancements of transportation infrastructure and greater community participation in disaster prevention and mitigation efforts (Ayuningtyas et al., 2021[25]; Pramono et al., 2020[26]). In addition, more extensive disaggregation of disaster data would allow for optimal targeting of policy (UNDRR, 2020[22]).

As regards earthquake risk mitigation, there is room for improvement in building code enforcement and understanding of local hazards (Pribadi et al., 2021[27]). Landslide risk awareness is an area that can be improved simply with more prevalent signage. At a policy design level, fostering communication between technical experts and policy makers would allow for easier maintenance of best practices (Zamroni, Kurniati and Prasetya, 2020[8]).

Streamlining the allocation of funds could benefit disaster risk financing in Indonesia (World Bank, 2020[28]). Local governments predominantly rely on contingency funds, which are often inadequate to meet recovery (Soetanto et al., 2020[29]; Fahlevi, Indriani and Oktari, 2019[30]). There is room to expand the use of ex-ante financing (Soetanto et al., 2020[29]) and CAT bonds or other sovereign insurance mechanisms can provide the government with the liquidity needed to support stronger response and recovery in the aftermath of severe disasters (Sakai et al., 2022[31]; OECD, 2024[32]).

References

[25] Ayuningtyas, D. et al. (2021), “Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation in Indonesia: A Narrative Review”, Iranian Journal of Public Health, https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i8.6799.

[6] Cepeda, J. et al. (2010), Landslide Risk in Indonesia, https://www.preventionweb.net/english/hyogo/gar/2011/en/bgdocs/Cepeda_et_al._2010.pdf.

[1] CRED (2024), EM-DAT, The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be (accessed on 12 December 2023).

[23] De Priester, L. (2016), “An approach to the profile of disaster risk of Indonesia”, Emergency and Disaster Reports, Vol. 3/2, pp. 5-66, https://digibuo.uniovi.es/dspace/handle/10651/36349.

[2] Djalante, R. et al. (eds.) (2017), Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54466-3.

[30] Fahlevi, H., M. Indriani and R. Oktari (2019), “Is the Indonesian disaster response budget correlated with disaster risk?”, Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, Vol. 11/1, pp. 1-9, https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/indonesian-disaster-response-budget-correlated-disaster-risk.

[18] Hodgkin, D. (2016), Emergency Response Preparedness in Indonesia: A Consultation Report Prepared Exclusively for the Indonesia Humanitarian Country Team, https://www.scribd.com/document/465225158/2016-emergency-response-preparedness-report-in-indonesia-eng.pdf.

[12] Horspool, N. et al. (2014), “A probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment for Indonesia”, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, Vol. 14/11, pp. 3105-3122, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-14-3105-2014.

[20] Jena, R., B. Pradhan and G. Beydoun (2020), “Earthquake vulnerability assessment in Northern Sumatra province by using a multi-criteria decision-making model”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 46, p. 101518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101518.

[10] Jufriansah, A. et al. (2021), “Analysis of Earthquake Activity in Indonesia by Clustering Method”, Journal of Physics: Theories and Applications, Vol. 5/2, p. 92, https://doi.org/10.20961/jphystheor-appl.v5i2.59133.

[17] Kumar, L. (ed.) (2015), “Future Coastal Population Growth and Exposure to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding - A Global Assessment”, PLOS ONE, Vol. 10/3, p. e0118571, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118571.

[14] Løvholt, F. et al. (2014), “Global tsunami hazard and exposure due to large co-seismic slip”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 10, pp. 406-418, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.04.003.

[24] Mardiah, A., J. Lovett and N. Evanty (2017), “Toward Integrated and Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia: Review of Regulatory Frameworks and Institutional Networks”, in Disaster Risk Reduction in Indonesia, Disaster Risk Reduction, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54466-3_3.

[13] Ministry of National Development (2005), Indonesia: Preliminary Damage and Loss Assessment, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/02aa8e6b-460a-3305-a9f0-39acd1325a7b/352868BF0EC9882885256F95005915EC-wb-idn-20jan.pdf.

[32] OECD (2024), Fostering Catastrophe Bond Markets in Asia and the Pacific, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ab1e49ef-en.

[15] Pasari, S. et al. (2021), “The Current State of Earthquake Potential on Java Island, Indonesia”, Pure and Applied Geophysics, Vol. 178/8, pp. 2789-2806, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-021-02781-4.

[26] Pramono, J. et al. (2020), “The Community Participation in Disaster Mitigation to Managing the Impact of Natural Disasters in Indonesia”, Journal of Talent Development and Excellence, Vol. 12, pp. 2396-2403, https://sirisma.unisri.ac.id/berkas/76957-Article%20Text-1691-1-10-20200601%20(1).pdf.

[5] Pratiwi, E. et al. (2020), “The Impacts of Flood and Drought on Food Security in Central Java”, Journal of the Civil Engineering Forum, Vol. 6/1, p. 69, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338935560_The_Impacts_of_Flood_and_Drought_on_Food_Security_in_Central_Java.

[27] Pribadi, K. et al. (2021), “Learning from past earthquake disasters: The need for knowledge management system to enhance infrastructure resilience in Indonesia”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 64, p. 102424, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102424.

[7] Rahardjo, N. and H. Marhaento (2018), “Application of IKONOS Imagery for Estimating Population Exposure to Landslide Hazard in Banjarmangu Sub District, Central Java, Indonesia”, 2018 4th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), https://doi.org/10.1109/icstc.2018.8528293.

[11] Reid, J. and W. Mooney (2022), “Tsunami Occurrence 1900–2020: A Global Review, with Examples from Indonesia”, Pure and Applied Geophysics, Vol. 180/5, pp. 1549-1571, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-022-03057-1.

[31] Sakai, A. et al. (2022), Sovereign Climate Debt Instruments: An Overview of the Green and Catastrophe Bond Markets. IMF Staff Climate Notes, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/staff-climate-notes/Issues/2022/06/29/Sovereign-Climate-Debt-Instruments-An-Overview-of-the-Green-and-Catastrophe-Bond-Markets-518272.

[29] Soetanto, R. et al. (2020), “Developing sustainable arrangements for “proactive” disaster risk financing in Java, Indonesia”, International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, Vol. 11/3, pp. 435-451, https://doi.org/10.1108/ijdrbe-01-2020-0006.

[21] Srikandini, A., D. Hilhorst and R. Voorst (2018), “Disaster Risk Governance in Indonesia and Myanmar: The Practice of Co-Governance”, Politics and Governance, Vol. 6/3, pp. 180-189, https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i3.1598.

[19] UNDRR (2022), Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2022: Our World at Risk: Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future, https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2022-our-world-risk-gar#container-downloads.

[22] UNDRR (2020), Disaster Risk Reduction in The Republic of Indonesia: Status Report 2020, https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/disaster-risk-reduction-indonesia-status-report-2020-0.

[16] UNFPA (2015), Population Exposed to Natural Hazards, https://indonesia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Population_Exposed_0.pdf.

[28] World Bank (2020), Project appraisal document on a proposed loan, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/316601611543685552/pdf/Indonesia-Disaster-Risk-Finance-and-Insurance-Project.pdf.

[4] World Bank and ADB (2021), Climate Risk Country Profile: Indonesia, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/700411/climate-risk-country-profile-indonesia.pdf.

[3] WRI (n.d.), AQUEDUCT Global Flood Analyzer, https://floods.wri.org/#.

[8] Zamroni, A., A. Kurniati and H. Prasetya (2020), “The assessment of landslides disaster mitigation in Java Island, Indonesia: a review”, Journal of Geoscience, Engineering, Environment, and Technology, Vol. 5/3, pp. 139-144, https://doi.org/10.25299/jgeet.2020.5.3.4676.

[9] Zhao, B., H. Liao and L. Su (2021), “Landslides triggered by the 2018 Lombok earthquake sequence, Indonesia”, CATENA, Vol. 207, p. 105676, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105676.