Emerging Asian economies are showing resilience.1 Economic growth in the region will be driven by robust domestic and regional demand and continued recovery of the services sector, particularly tourism. The improvement of financial conditions is expected to continue this year. However, the region will face several challenges, such as external headwinds; the impact of extreme weather; and elevated levels of debt, particularly mounting private debt.

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2024

Overview

Growth in Emerging Asia remains resilient but faces challenges and risks

Merchandise trade in Emerging Asia show signs of recovery

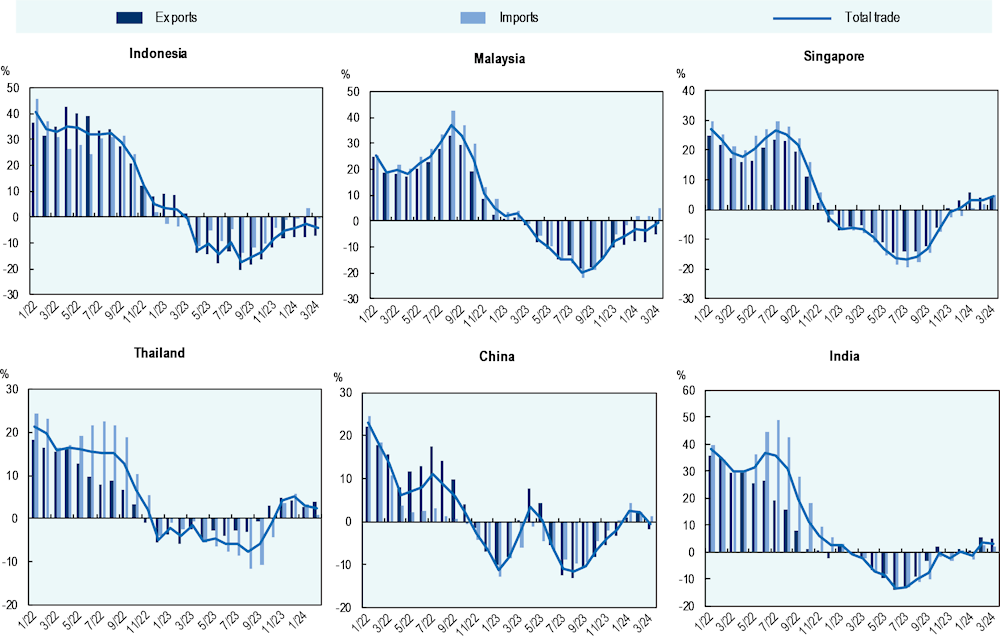

Recent merchandise trade data in the initial months of 2024, however, are showing signs of recovery in most economies of the region (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total merchandise trade in selected Emerging Asian economies

January 2022 to March 2024, year-on-year percentage change

The ASEAN and China’s manufacturing sectors showed signs of improvement in the first quarter of 2024 with their Purchasing Managers’ Indexes (PMIs). India’s manufacturing sector remained resilient with PMI surging to a record high in March, continuing to expand with higher intake of new business.

Services trade will remain resilient to global challenges

Weak performance in goods trade in the region will be somewhat offset by growth in services trade. The growing digitalisation of services and the complete relaxation of border restrictions post-pandemic have spurred recovery in the travel and tourism sectors. Their strong rebound is supported by the return of international air passenger traffic to pre-pandemic levels.

The tourism industry is expected to be another important growth driver for ASEAN exports over the medium term. International tourism flows are expected to show robust growth as per capita household incomes in large Asian consumer markets continue to increase rapidly, driving international travel to ASEAN tourism destinations. This will help ASEAN economies where tourism contributes a significant share of total GDP, including Thailand, Cambodia and the Philippines.

Foreign direct investment should pick up in the near term

Investment patterns worldwide, and particularly foreign direct investment (FDI), weakened in 2023 on the back of tight global financial conditions, higher uncertainty amid intensified geopolitical tensions and the unwinding of pandemic-related fiscal support measures. Emerging Asia, an engine of FDI growth, experienced declines in 2023. For instance, FDI dropped by 16% for ASEAN and by 6% for China.

However, the attractiveness of the region for manufacturing investments remains robust, supported by growth in greenfield project announcements. Emerging Asia’s trade links will be strengthened through a gradual increase of FDI, particularly in the semiconductor and automotive industries. High-tech products and the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital services are expected to be major drivers of growth in regional trade in the long term and to attract a sizeable share of FDI.

Financial market conditions will continue to improve while remaining vulnerable to tight policy rates

Financial market sentiment in the region fluctuated in 2023 amid global uncertainty and changing views about possible rate cuts by monetary policy makers in OECD economies. Currencies in the region continue to weaken amid uncertainty about the timing of interest rate reductions. In the second half of 2023, expectations that the US Federal Reserve would keep key interest rates elevated for an extended period led to further weakening of financial conditions in the region. Monetary authorities in the region resumed hiking key interest rates to keep inflation in check and safeguard financial stability. Policy rates remain tight to date, as policymakers continue to manage lingering inflationary pressures.

The financial market outlook will remain stable in 2024 in general. Local-currency bonds in major economies in the region are expected to improve in the later months of the year, as such rate cuts are likely to strengthen Asian currencies against the dollar, boosting Asian local-bond returns. However, persistently elevated inflation in the US coupled with possible spike in oil prices amidst increased tension in the Middle East could increase uncertainty in monetary policies and will have a longer period of high interest rates.

Extreme weather, including events brought about by El Niño, adds to concerns about growth

Emerging Asia has faced several episodes of extreme weather recently. Of the 20 cyclones that have produced the fastest sustained wind speeds in the region since 2000, 19 have occurred since 2019 and the other occurred in 2018.

The onset of El Niño in Emerging Asia can lead to higher air temperatures and limited precipitation along with more frequent extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and storms. Climate change will exacerbate these events, increasing the likelihood of record-breaking surface air temperatures. These can have significant impacts on crop yields and livestock, water supply and labour productivity. Warmer weather conditions also decrease water resources for energy generation and create higher demand for energy. In addition, extreme weather events such as cyclones can have significant negative effects on tourism-related income.

The impact of extreme weather on growth is more pronounced for countries with a larger share of agricultural activity in GDP such as Myanmar, Lao PDR, Cambodia and India. The adverse impact of El Niño events can also exacerbate inflationary pressures on food products and other primary commodities, particularly those with prices that remain above 2021 levels. Rice and palm oil are among the commodities that will be most affected. Declines in production volumes in conjunction with soaring prices may threaten food security in the region.

Mounting private debt poses a risk

Concerns regarding debt management are increasing. Although, public debt has remained stable overall, many economies still face public debt levels larger in size than historical trends. More importantly, private debt (especially household debt) remains a risk to growth prospects in Emerging Asia.

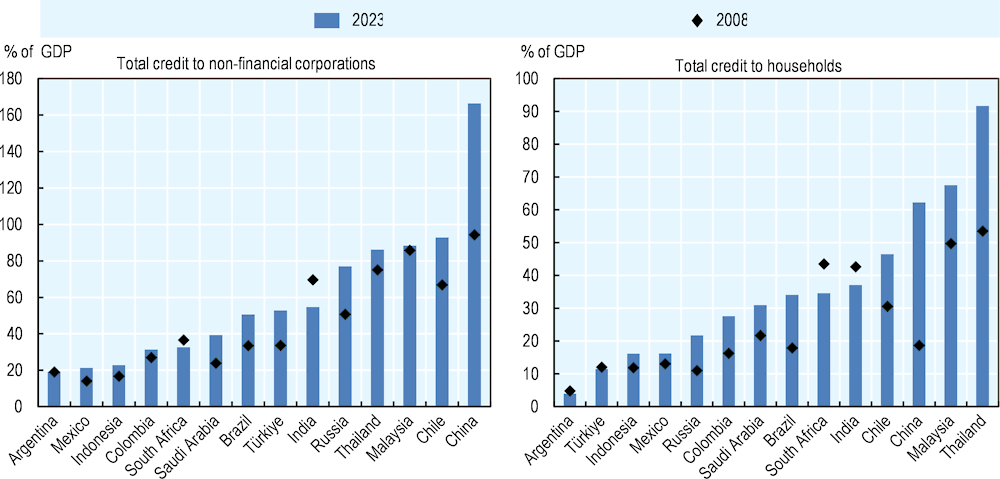

Private debt in some Emerging Asian economies rose considerably during a prolonged period of accommodative monetary policy. The global financial landscape changed dramatically after supply-driven inflationary pressures persisted long enough to initiate a significant modification in the monetary stance of major central banks. The result was a synchronous rise in interest rates globally and tightening domestic financial conditions in the region. This increased debt payments and now threatens to cause financial distress among indebted households and corporates, especially in economies with larger private debt stocks. Total credit to non-financial corporations as a proportion of GDP averaged 22.9% in Indonesia, 54.6% in India, 86.2% in Thailand, 88.3% in Malaysia, and 166.4% in China over the first three quarters of 2023. Household debt as a proportion of GDP averaged 16.1% in Indonesia, 37.1% in India, 62.3% in China, 67.5% in Malaysia, and 91.7% in Thailand over the same span (Figure 2).

Excessive debt stock and increasing debt service costs can force households to prioritise debt repayment, with fewer resources available for consumption. Likewise, financially distressed corporations can choose to deleverage and spare limited funds for investment. These responses could weaken economic growth. In addition, the recent deflationary environment in China and Thailand complicates matters concerning private debt. Debt deflation could emerge from decelerating money supply growth, decreasing asset prices and damaged credit intermediation against the distressed selling of assets and debt repayment efforts.

Figure 2. Private debt in selected emerging market economies

Note: The chart shows total credit to non-financial corporations and total credit to households during 2023 Q1-Q3 and 2008 Q1-Q3.

Source: BIS.

Emerging Asia needs holistic approaches to disaster resilience

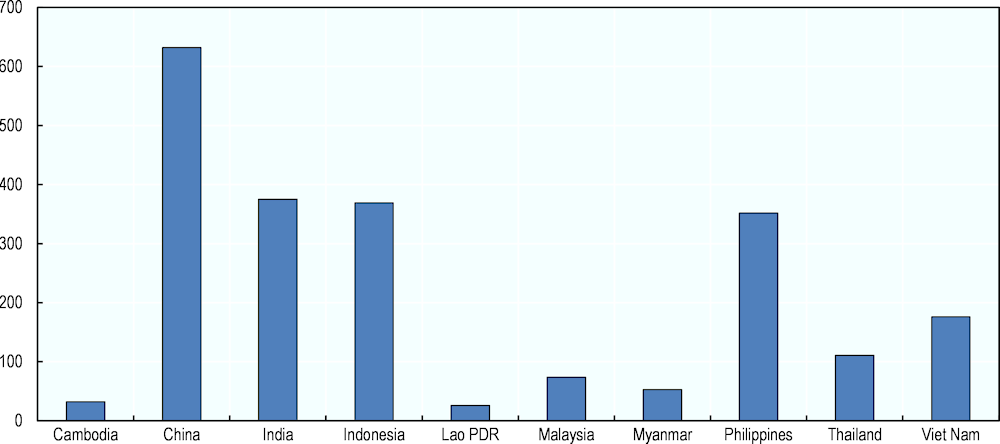

The countries of Emerging Asia are in the world’s most disaster-prone region (Figure 3). They are affected by earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, floods, storms, landslides, droughts and forest fires.

Figure 3. Total disaster occurrences in Emerging Asian countries, 2000-23

Note: The figure only includes disasters with available data. Disasters include drought, earthquake, extreme temperature, flood, glacial lake outburst flood, mass movement (dry, wet), storm, volcanic activity, and wildfire.

Source: Data from the EM-DAT database (CRED, 2024[1]).

Beyond their short-term effects, disasters hinder the achievement of long-term development and sustainability. Vulnerable groups and communities are particularly endangered by disasters, as economic and social structures are often compromised. Reducing disaster risk and increasing resilience are therefore crucial for development in the countries of Emerging Asia.

Achieving disaster-resilient development requires strategic development of a holistic policy approach that includes a combination of ex-ante and ex-post policies. Robust co-ordination underpins the success of such an approach.

The policy areas on which this publication builds its holistic approach are:

improving governance and institutional capacity

ensuring an adequate budget for disasters

broadening disaster risk financing options

investing in disaster-resilient infrastructure

establishing comprehensive land-use planning

developing disaster-related technology

strengthening disaster risk reduction education

improving health responses to disasters

facilitating the role of the private sector.

Transforming governance and improving institutional capacity amid rising disaster risks

Despite their commitments to build disaster resilience, many countries in Emerging Asia still have weak strategies for reducing disaster risk. They need to adapt their institutions and governance systems to cope with increasing disaster risks.

Effective disaster risk management requires a proactive approach

Disaster management and response require a holistic institutional perspective that accounts for cross-sectoral and multilinear levels of governance, and for the cascading impacts of disasters on the economy and society. Most national and local governments in Emerging Asia currently take a reactive approach to disasters. However, effective disaster risk management requires a proactive approach.

Well co-ordinated systems can help local authorities and communities cope with disasters

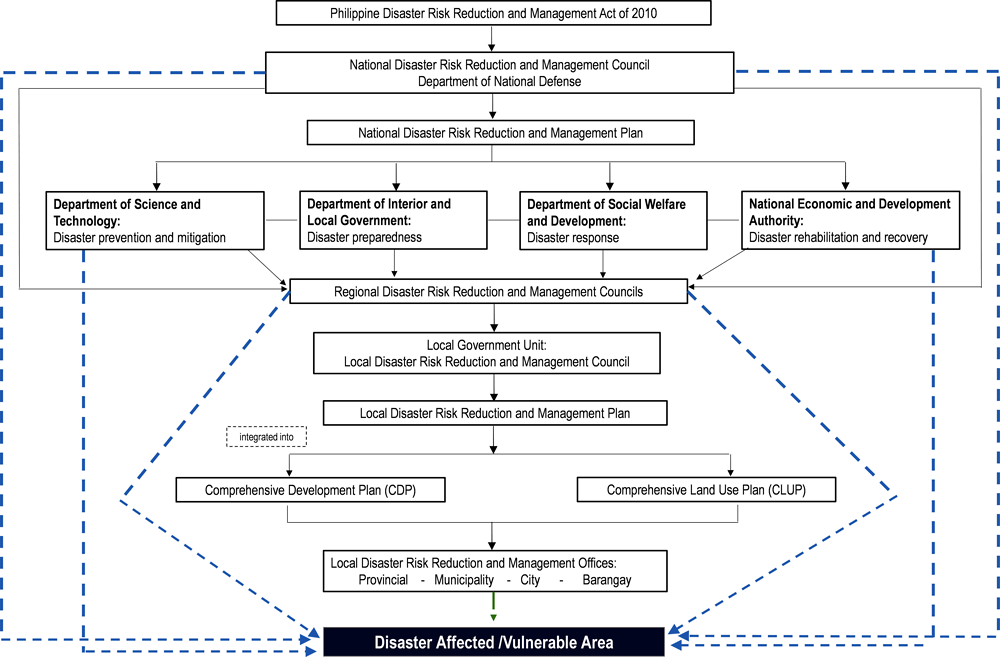

Systems where central and local authorities are well aligned could empower local authorities and communities to take an active role in disaster preparedness and response. Strengthening co-ordination, bringing cohesion to fragmented disaster response plans, increasing capacity and skills, and reducing disparities in resources among regions are critical objectives. Figure 4 lays out the system of disaster risk management co-ordination in the Philippines as an example of how a well co-ordinated system is backed by legislation, incorporates all levels of government, and delegates responsibilities among them and various agencies.

Figure 4. The Philippines’ Implementation Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management

Source: Authors, based on national sources.

Disaster resilience requires clarity on laws, regulations and responsibilities

Most countries in Emerging Asia face legal challenges that impede the effectiveness of disaster preparedness, response and recovery. Governing institutions at all levels can face fragmented rules, with multiple laws, regulations and policies. A lack of clarity on roles, responsibilities, lines of command and co‑ordination mechanisms contributes to challenges in the disaster response phase. Procedural standards and response guidelines remain weak, and administrative hurdles hinder the development of effective disaster risk management systems.

Comprehensive monitoring and evaluation are key to managing disaster risk

Well-developed monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems are crucial to ensuring that disaster risk management efforts are effective, efficient and accountable. Efforts to develop M&E systems for disaster risk management in Emerging Asia have not been comprehensive and face several common issues, such as data deficiency, resource constraints, capacity gaps and weak political will. A robust M&E system across countries in Emerging Asia is essential in order put in place: i) the prioritisation of disaster risk management projects and activities; ii) a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, with accountability for disaster risk management outcomes; and iii) appropriate, clear and identified funding sources for disaster risk management efforts.

Ensuring adequate budgets for coping with disasters in Emerging Asia

Lack of funding is a significant roadblock to disaster preparedness and recovery in Emerging Asia. Budgets for both preparedness and response are, in general, below what is needed to put the region on track for long-term readiness for disasters. In particular, increasing the availability of funds for ex-ante disaster risk reduction measures is critical. Governments can take various steps to bolster their budgets for disaster risk management. Local governments’ disaster budgets may be tied to local fiscal income; in which case the adequacy of the resulting budget must be ensured.

Broadening disaster risk financing requires a grand design

Effective disaster risk financing requires formulating a grand design that covers the entirety of the economy. Such a grand design has two main pillars: a risk-pooling function and a risk-transfer function. Pooling risk, typically in the form of insurance, improves resilience. Risk transfer typically takes place through market-based solutions such as insurance-linked securities or catastrophe (CAT) bonds. Coherent strategies for building financial resilience to disasters involve an approach that provides financing to all levels of government.

Improving access to disaster insurance is crucial

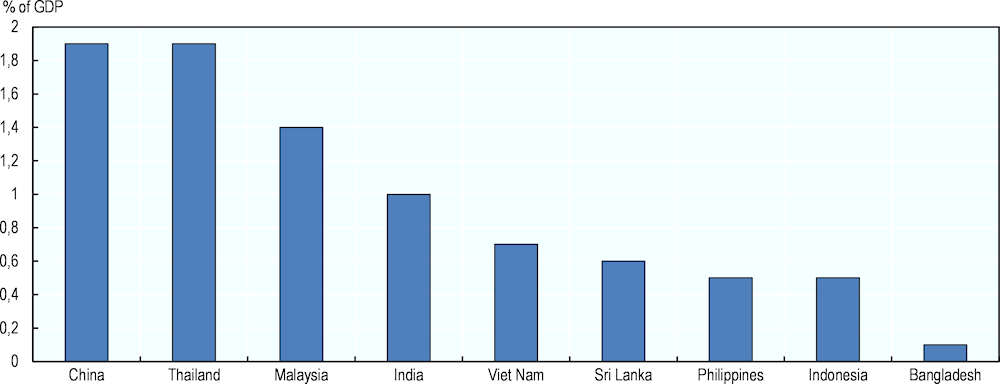

Disaster insurance is crucial for bridging the disaster financing gap in Emerging Asia. Developing the private insurance market in the region is proving challenging. Barriers hindering insurers from offering pure private disaster insurance solutions exist on both sides of the market. On the supply side, major obstacles can include insufficient capital and limited reinsurance capacity; the degree of freedom to manage the underwriting process; and data availability. Demand side barriers can include risk perception among consumers; price, availability and scale of public disaster relief; and claim-payment efficiency. These barriers work in concert to reduce insurance penetration rates in Asia (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Insurance penetration in selected Asian countries, 2021

Premiums as % of GDP

Source: Swiss Re (2022[2]), “World insurance: Inflation risks front and centre”,

https://www.swissre.com/institute/conferences/world-insurance-inflation-risks.html.

To address insufficient market-based insurance and make risk transfer mechanisms more accessible and affordable, governments can take various measures. For instance, governments can encourage insurance uptake by subsidising premiums where necessary or offering support to private insurers to help them take on clients facing particularly high disaster risk. Governments can transfer some of their own risks to markets using tools such as catastrophe bonds, though doing so requires developed financial markets and regulatory frameworks. At the same time, helping households and firms develop appropriate understandings of the financial risks associated with disasters and the benefits of disaster insurance is an essential component of disaster risk reduction education. Practical training on how to use this knowledge is also essential.

Community-based approaches can be used in disaster risk financing

Microfinance programmes offer an example of financial solutions based on community enforcement. Such programmes can provide insurance to those unable to access traditional markets. However, the flexibility offered by microfinance programmes may come at the cost of high interest rates. Thus, they must be properly structured to remain accessible amid post-disaster financial challenges. In addition to microfinance, agriculture insurance can help to protect farmers from the financial impacts of disasters.

Catastrophe bonds offer an alternative means of disaster risk finance

The adoption of market-based tools for transferring disaster risk is also important. Catastrophe (CAT) bonds provide an alternative to traditional sources as part of a country’s disaster risk financing menu. CAT bonds securitise disaster risk and transfer it to capital markets. The CAT bond market has grown steadily since the 1990s, though growth has been heavily concentrated in the United States and Europe. In order to benefit maximally from CAT bonds, countries need to take some or all of the following actions: construct a grand design for disaster risk finance; invest in measurement infrastructure and enhance the quality of disaster data; use disaster data to develop tailor-made catastrophe risk models; enhance capacity building for finance and insurance officials; broaden investor bases; construct CAT bonds in a manner that minimises basis risk; prepare distribution schemes for the funds; and develop local-currency bond markets (OECD, 2024[3]).

Investing in disaster-resilient infrastructure

A range of challenges must be addressed to scale up disaster-resistant infrastructure.

The effective planning and implementation of resilient infrastructure projects is impeded by limited application of disaster risk assessments.

Major capital investment and effective financing methods are needed for the construction of disaster-proof infrastructure, and maximising private-sector participation will be crucial as government revenues will not be enough to bridge the financing gap in the long term.

Operation and maintenance approaches that can support disaster resilience before, during and after catastrophic events should be prioritised, with the collaboration of government, private investors and other stakeholders at both project and policy levels.

Institutionalising the monitoring and evaluation of infrastructure projects is important to ensure regular risk assessment as climate and socioeconomic vulnerabilities arise.

Effective collaboration among multiple stakeholders with a diverse range of skills and perspectives fortifies disaster-resilient infrastructure by enriching the decision-making process in project design and planning, and by ensuring comprehensive risk assessment and mitigation strategies.

Preserving and developing infrastructure during and after disasters is necessary to ensure the resilience and recovery of the impacted region, including allocating public space to serve as protective barriers during a disaster and rebuilding transport infrastructure.

Integration of nature-based solutions (NbS) into disaster-resilient infrastructure development is crucial. The balanced integration of nature-based solutions and grey infrastructure could offer a more effective and sustainable solution for comprehensive disaster risk management (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison between grey infrastructure and NbS in flood risk management

|

Characteristics |

NbS |

Grey infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

|

Time scale |

Takes longer for the benefits to materialise |

Benefits are immediate after construction |

|

Spatial scale |

Typically executed on a larger scale to be effective, encompassing multiple jurisdictions |

Typically implemented within individual jurisdictions |

|

Performance reliability |

Uncertain performance due to complexity of natural systems |

Performance is more predictable |

|

Flexibility |

Adaptable to changing environmental conditions as they are part of the natural landscape |

More rigid and with limited adaptability as it typically provides a fixed solution for flood management |

|

Sustainability |

More sustainable as it involves the restoration of natural ecosystems |

Can have negative impacts on the environment, e.g. increased erosion, altered hydrology and destruction of natural habitat, and requires significant maintenance and upgrades over time |

|

Multifunctionality |

Provides multiple benefits beyond flood risk reduction |

Often has a more singular focus on reducing flood risk and rarely provides additional benefits |

|

Quantification of benefits |

Co-benefits are difficult to quantify, e.g. human health and livelihoods, food and energy security, biodiversity |

Benefits are easy to quantify, e.g. prevention of damage to assets |

|

Community engagement |

Design, implementation, and maintenance involve local communities, hence promote community ownership and resilience |

Designed and implemented by external engineers and experts, hence limited community engagement and lack of local ownership |

Source: (Molnar-Tanaka and Surminski, 2024[4]), “Nature-based solutions for flood management in Asia and the Pacific”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers No. 351.

Addressing disaster-related migration and improving land-use planning

Emerging Asian countries have experienced considerable migration and displacement because of disasters, with consequences that affect not just migrants and their families but also their nations of origin and destination. Making developmental investments for forcibly displaced individuals and host communities can alleviate the adverse consequences of displacement. Policies to facilitate disaster-induced migration where necessary and to otherwise reduce displacement include:

establishing a framework that categorises displacement by mapping and monitoring potential environmental risk areas and adapting to changing regional conditions

allocating more resources to disaster readiness to mitigate disaster impacts and the ensuing displacement

refining and expanding the policy focus on social and community resilience and adaptation, especially concerning the social dynamics of resettlement

ensuring community-focused interventions, particularly for displaced and economically vulnerable communities

promoting the integration of environmental policies and responses in relief, recovery and development programmes

incorporating climate-change adaptation strategies into disaster management policies

encouraging community involvement in disaster management, as local communities have a superior understanding of their vulnerabilities and capacities.

Natural hazards also have a substantial impact on land-use planning in Emerging Asian countries. Comprehensive land-use planning is crucial for identifying the goals of communities in disaster-prone areas. Such plans can help to direct development away from vulnerable land, lay the foundations for space acquisition and nature conservation campaigns, and encourage the utilisation of natural topography for disaster mitigation. Recommendations on improving the efficiency of land use for disaster resilience encompass a range of topics.

Alterations in land-use due to urbanisation have transformed agricultural land, forests and extensive coastal areas into built environments. In the face of evolving disaster risks, it is important to provide a proactive and sustainable approach to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience through strategic planning, community engagement and the integration of ecosystem-based approaches.

New land-use regulations can be imposed following a disaster to steer reconstruction efforts towards resilient, safe and sustainable development.

Land-use management is a comprehensive approach that seeks to balance competing demands on land resources while promoting sustainability, resilience and the well-being of communities and ecosystems.

Risk-sensitive land-use planning is a widely acknowledged non-structural risk mitigation measure with the potential to avoid exposure in the most hazardous zones and to reduce exposure and vulnerability over time in urbanised areas. Regulatory approaches could include the use of zoning to prevent or curb development or to minimise vulnerability.

Restrictions on development can be implemented to prevent further settling of vulnerable areas.

Property buy-outs and acquisition of open land may be considered as means of supporting owners of damaged properties, establishing and safeguarding buffer zones, and removing vulnerable land from the market.

Relocation of infrastructure away from disaster-vulnerable areas can be the best way of preventing repeat damage. However, the restoration of infrastructure is often critical to post-disaster recovery, and the use of public assistance funding must be balanced between restoration and relocation projects.

Developing disaster-related technology

Policy makers in Emerging Asia can explore a range of technologies for use in disaster risk reduction and management. They include resident-engaged disaster risk mapping, early warning systems (EWS), information and communications technology (ICT), disaster management platforms, physical infrastructure for alleviating the impact of disasters, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) such as drones, and social media.

Recent advanced technologies with the potential to bolster disaster risk management capacity are not yet fully utilised in Emerging Asia. They include Internet of Things (IoT) technologies such as cloud computing, broadband wireless networks and devices with sensors; drones, which can reach otherwise inaccessible places and detect things beyond human capabilities; search-and-rescue robots; big data; artificial intelligence (AI); and blockchain technology.

For the successful adoption of new technologies related to disaster management, governments can provide support for research and development (R&D) investment in such technologies; embrace open- and fair-trade policies that improve access to foreign markets and increase competition, which encourages firms to invest more in R&D; and enact policies that strengthen the country’s capacity to deploy and provide access to new technologies.

Key requirements for the successful adoption of new technologies include: i) resilient and state-of-the-art telecommunications infrastructure, including mobile internet coverage and smartphone penetration; ii) technical skills for the use of AI and spatial analysis tools; iii) access to data and software; iv) human capital formation and user education; and v) regulatory adaptation, with new regulatory frameworks to facilitate early acceptance of new tools.

Strengthening disaster risk reduction training and education

Given the increasing frequency and intensity of natural hazards, disaster-prone countries are paying far more attention to the role of disaster risk reduction education (Table 2). Most of the region’s countries have integrated disaster risk reduction education into existing curricula or extracurricular activities, while other disaster preparedness and response programmes have been launched to improve public awareness at the societal level.

Table 2. Disaster Risk Reduction Education Initiatives in selected Emerging Asian countries

|

Country/Region |

Initiation Year |

Name of Initiative |

Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

|

India |

2004 |

Disaster Management Curriculum in Class V, VIII, IX, X, XI |

Integrating disaster management curriculum which includes basic concepts of the most commonly occurring disasters |

|

Thailand |

2015 |

Comprehensive School Safety (CSS) |

Provision of teacher training to support teachers to design disaster risk reduction activities in schools |

|

2023 |

The Implementation of Disaster Education under National Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Plan 2021-2027 under MOU between Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation and Ministry of Education |

Developing disaster curriculum and disaster preparedness activities in schools and other educational institutions; promoting disaster risk reduction activities in schools to create public awareness and enhance participation among students, teachers, administrators, and support staff |

|

|

2023 |

Implementation of disaster risk reduction education through the Thai Network for Disaster Resilience (TNDR) |

Sharing best practices in terms of disaster risk reduction among experts and with others through 17 universities in Thailand |

|

|

Indonesia |

2019 |

Satuan Pendidikan Aman Bencana (SPAB) |

Deliver instruction on prevention and management of the impact of disasters via educational institutions such as integration of disaster risk reduction education into K-13 curriculum |

|

China |

2024 |

Student Safety Education campaign |

An educational campaign to strengthen risk preparedness and self-protection awareness among primary school and secondary school students, including fire safety, traffic safety and first-aid training |

|

Philippines |

2013 |

K-to-12 curriculum |

Inclusion of Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Education into school curriculum |

|

ASEAN |

2015 |

ASEAN Common Framework on School Safety |

Ensuring safe learning facilities and reinforcing school disaster management capacities |

Source: Authors, based on national sources.

Countries in Emerging Asia face challenges in providing efficient disaster education for students, the public and other stakeholders. To meet these challenges, governments should set overarching, clear and mandatory policies for disaster risk reduction education at the national level that outline specific requirements for disaster preparedness in schools, including curriculum content, teacher training and emergency response protocols. Implementation should be adapted to local contexts to tailor disaster risk reduction education programmes to regional risks and needs; it is vital that remote villages and islands receive necessary support and resources given their increased vulnerability to disasters.

The central government and local authorities should ensure that learning materials are updated regularly, and the curriculum should be complemented by active learning methods including simulations, drills, role-playing, games and contests that enable students to apply the knowledge acquired from lecture-based education practically.

Another challenge is the lack of monitoring and evaluation of educational programmes. To measure progress in the implementation of disaster risk reduction education policies, the role of government involves: setting the goals of disaster risk reduction education initiatives; developing indicators for quantification; arranging tools for data analysis; involving a range of stakeholders in multidimensional evaluation; and providing measures for self-assessment.

Teachers should receive regular training with updated information to ensure accurate knowledge transfer, effective teaching strategies and enhanced emergency response skills. Policies are needed that encourage programmes such as community workshops, public awareness campaigns and seminars with experts.

Disaster prevention learning facilities offer interactive and realistic experiences where individuals learn practical skills, such as evacuation simulation or how to use fire extinguishers properly. Training in digital literacy is also an essential component of disaster risk reduction education, as vital information such as early warning messages and the locations of shelters and evacuation routes is now mainly disseminated via online platforms.

Improving health responses to disasters in Emerging Asia

The health impacts of disasters are often enormous. The injuries suffered can be acute and may lead to lasting disability. Disasters can also spawn mental health issues originating from trauma and stress. All Emerging Asian countries have plans for directing health responses when a disaster strikes (Table 3).

Table 3. Health responses to disasters in Emerging Asia

|

Country |

Health responses |

Mental health responses |

|---|---|---|

|

ASEAN-5 |

||

|

Indonesia |

Rencana Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana 2020-2024 addresses health service provision |

Funds from national and subnational budgets contribute to Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in disaster recovery |

|

Malaysia |

Crisis Preparedness and Response Centre (CPRC) and subnational CPRC within health departments responsible |

National Guidelines for Mental Health and Psychosocial Response to Disaster |

|

Philippines |

Health Emergency Management Bureau clusters provide health services in disasters. National Emergency Medical Teams assist local government units as needed |

The Health Emergency Management Bureau has a MHPSS cluster |

|

Thailand |

Local governments must budget for health services in disasters. Local governments respond but more severe disasters receive higher level responses |

Health-related and social well-being rehabilitation includes MHPSS, Ministry of Public Health |

|

Viet Nam |

Ministry of Health (MOH) has a Commanding Committee for Natural Disaster Prevention and Control, Search and Rescue (CCNDPC/SAR); MOH and provincial departments participate in the disaster risk management system; Health Sector Action Plan |

National Steering Committee for National Disaster Prevention and Control collaborates with a disaster risk reduction partnership composed of national and international organisations |

|

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore |

||

|

Brunei Darussalam |

The Public Health Emergency Operation Plan co-ordinates efforts of the National Disaster Management Centre and Ministry of Health (MOH) and gives the MOH authority over health responses to disasters. |

Brunei Darussalam Mental Health Action Plan 2021-2025 designates developing national disaster mental health management guidelines or incorporating mental health in National Emergency Preparedness Plan as a priority action |

|

Singapore |

Singapore Emergency Medical Team on call in hospitals always |

Disaster Mental Health Programme for Communities in Asia organises forums and training sessions open to all of Asia |

|

CLM countries |

||

|

Cambodia |

National Strategic Plan on Disaster Risk Management for Health 2020-2024 |

MHPSS response is a priority strategy under the National Strategic Plan on Disaster Risk Management for Health 2020-24 but is absent from the Mental Health Strategic Plan 2023-32. |

|

China and India |

||

|

China |

National Emergency Management System Plan developed during the 14th Five-Year Plan Period |

MHPSS support in schools, training for rural health professionals, online lectures for public |

|

India |

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare collaborates with the Armed Forces |

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services in Disasters (December 2023) |

Source: Authors, based on national sources, intergovernmental organisations and (Li et al., 2022[5]).

Health responses to disasters require intricate co-ordination

Health responses to disasters require efficient and robust plans for co-ordination among agencies and levels of government. While disaster management authorities are often central bodies, aspects of healthcare systems may be managed at local levels. Clear lines of communication must be established between central and local government officials so that all parties can assess needs and capacity to assist. Roles of involved bodies should be clearly defined, with minimal overlap.

The health of the general population must be preserved during disasters

Disaster management organisations must not only contend with injuries or illnesses acquired during disasters but also work to preserve the health of the population. It is vital to ensure that those affected by disasters have access to clean water, along with hygiene equipment and supplies. Food and water security and health services must be preserved as well. Care must also continue for pregnant women, people with chronic medical conditions and those hospitalised prior to a disaster.

Resource flexibility facilitates disaster response

Flexibility is necessary to meet the need to redistribute medical equipment and supplies during a disaster. Maintaining accurate data on medical personnel, hospital and resource capacity at all levels of administration can help policy makers decide how best to allocate resources. Depending on the location and type of a disaster, local health-related physical and human capital might be insufficient. Health authorities should maintain a stockpile of critical equipment and supplies in a usable state.

Mental health care in the aftermath of a disaster is crucial

Disaster preparedness requires the training of medical personnel to deal with mental health issues such as trauma and stress. However, mental health services are scarce in Emerging Asia, with the proportion of psychologists and psychiatrists in the population in most countries far below the OECD average. Scarcity issues become even more concerning when the needs of different populations are considered. Mental health services should therefore be scaled up, including via digital services, with specialised services for vulnerable groups such as women, children and migrant workers.

Facilitating the role of the private sector

The private sector in Emerging Asia faces significant challenges due to insufficient risk assessment, limited insurance coverage, weaknesses in supply-chain management, deficient co-ordination, and economic downturns and joblessness.

These challenges are spurring efforts from the private sector to improve disaster preparedness and management on its own. Adaptation measures by private firms across Emerging Asia include expanding and diversifying supply chains to decrease reliance on singular sources and locations susceptible to disasters; evaluating potential hazards and vulnerabilities; formulating contingency plans to handle risks effectively; formulating business continuity plans to guarantee the uninterrupted operation of critical business functions during and following a disaster; collaborating with other stakeholders, especially the government; and procuring insurance policies as a safeguard against losses arising from disasters.

Governments can enact policy measures aimed at enhancing the capacity of the private sector to manage and recover from disasters. Such measures include evaluating the susceptibility of all sectors to disasters, including the private sector; boosting disaster risk governance; mobilising public-private partnerships when investing in disaster resilience; and encouraging the growth of private catastrophe risk insurance markets.

Country notes on disaster risks

ASEAN-5

Indonesia is exposed to hydrometeorological disasters such as floods, droughts, cyclones and heatwaves, and geophysical disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and landslides. Improved co-ordination among levels of government, and between governments, will be a priority along with capacity building for local officials. Improvements to building codes would mitigate earthquake risk, and a simple increase in signage indicating vulnerable areas would mitigate landslide risk. Disaster risk financing should be streamlined beyond contingency funds.

Malaysia is exposed to floods, droughts, landslides, fire-associated haze episodes and tsunamis. The country could improve a legislative framework to integrate disaster risk management with broader policy objectives. Policies should be developed to establish the duties of stakeholders to mitigate and respond to floods; to optimise coastal land use; and to discourage development in areas prone to landslides. Disaster risk management would benefit from the integration of disaster risk financing into budgets at all levels, as well as an expansion of human and financial capital at the local level. Public-private partnerships could assist in overcoming some of these barriers.

The Philippines ranks as the country facing the highest disaster risk according to the WorldRiskIndex 2023. It is exposed to typhoons, floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and droughts, with typhoons and floods being the most frequent and damaging disasters. The population is concentrated in vulnerable areas, with more than 90% exposed to floods, cyclones or earthquakes. Rapid urbanisation and climate change have exacerbated this problem in recent years. The government has increased its efforts to develop disaster risk management institutions and bolster resources. Mismatches between available funding for a given province and the disaster risk it faces can create financial constraints, and local-level institutions need increases in capacity. Land planning regulations should be enforced more stringently, and disaster risk education must be expanded, especially to those outside of formal schooling.

Thailand faces floods, droughts, cyclones, landslides, earthquakes, tsunamis, wildfires and heat waves. Floods are particularly damaging. Heavy rainfall can also trigger landslides in mountainous areas. Agricultural areas are vulnerable to disasters due to lower levels of development, while urban areas are vulnerable due to population density. The National Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Response Plan provides a robust guide to disaster risk management, though measures remain largely ad hoc and focused on responses. Flood prevention and mitigation efforts were significantly expanded in the aftermath of floods in 2011, though there is still room for improvement in water management. Implementing methods of storing floodwater could reduce water shortages, while adjustments to forest conservation policy could discourage farming and other development in flood-prone areas. Moving to an approach underpinned by stronger risk assessments and risk transfer would help alleviate financial stress.

Viet Nam is highly exposed to floods, cyclones and landslides, and faces lesser threats from droughts, earthquakes, tsunamis and heatwaves. Flooding threatens jobs in agriculture, aquaculture, tourism and manufacturing, while some areas of the country are at considerable risk of inundation due to sea level rise. Disaster risk management would benefit from stronger co‑operation among agencies, levels of government and the private sector; and enhanced local-level disaster data. Disaster risk could be reduced by upgrading existing infrastructure, and by enhancing the capacity of urban planners to develop stronger building codes, safety standards and enforcement. The government faces disaster risk financing shortfalls. As urban and peri-urban areas are currently experiencing the most rapid increase in flood risk, more robust urban planning policies that account for flood risk should be enforced.

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore

Brunei Darussalam is perceived to be at minimal risk of disasters, yet the country faces floods, landslides, droughts, storms and wildfires, and there are large numbers of vulnerable people. Floods and landslides with significant effects occur annually. Small-scale individual flood mitigation measures and an enhanced capacity to forecast heavy rainfall could help reduce risks linked to floods. Early warning systems for disasters require significant modernisation, as they currently require significant manual operation and often fail to reach coastal fishing communities and ships offshore. Monitoring and forecasting systems for landslides and forest fires should also be improved.

Singapore is exposed to floods, droughts, storms, heatwaves, earthquakes and tsunamis, but such occurrences are rare. Droughts have increased in recent years, but prudent water management has mitigated the effects. Flood risk could be mitigated via household- and firm-level measures such as the elevation of buildings or flood-proofing of properties. Policy makers could consider incentives for households and firms to take these actions. While disaster risk management is robust, there is room for improvement in data management, by building a comprehensive disaster risk database for example. The country would also benefit from enhancing food and water security management and fostering stronger public-private partnerships.

CLM countries

Cambodia is exposed to floods, landslides, droughts and tropical storms. As the plains along the Mekong River and surrounding the Tonlé Sap Lake cover almost three-quarters of the country, Cambodia is highly exposed to floods, which cause about 100 deaths and at least USD 100 million in agricultural losses annually. Irrigation management is currently the main method of flood control, but it is insufficient, and should be complemented by water-diversion schemes and reservoir construction. The country also faces droughts caused by El Niño, and large-scale droughts can threaten national food security.

Lao PDR is exposed to floods, droughts, tropical cyclones, landslides and earthquakes, but as a landlocked country it is less exposed to disaster risk than other countries in Emerging Asia. Impacts of drought have been increasing, and severe El Niño conditions are expected to cause extreme drought in northern Lao PDR in the future. Given the large share of the population dependent on subsistence agriculture, food security can be severely threatened by floods and droughts. More robust drought risk assessments and more efficient early warning systems would enhance drought risk management, while flood risk management could be improved simply by encouraging farmers to adopt practices to mitigate flood effects, such as using flood-resistant crop storage and moving livestock to higher ground in the event of flooding. Improved data collection, analysis and management would greatly assist the formulation of policy at all levels of government. Major financing concerns include severe funding shortages that inhibit disaster risk reduction and relief. Lao PDR introduced a National Financial Protection Strategy Against Disaster Risk in August 2023 meant to address the dearth of disaster insurance coverage.

Myanmar, one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, is exposed frequently to floods, droughts and tropical cyclones, and occasionally to landslides, earthquakes, tsunamis and wildfires. Disasters have a large cumulative impact on development and cause major negative spillovers, including poverty traps, reduced labour-force participation and the financial exclusion of women. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of floods, storms and droughts, which will exacerbate these problems. Disaster resilience could be enhanced through activities such as education in first aid, improving mobile phone infrastructure and using disaster-resilient public buildings as shelters. Severe funding gaps remain for both ex-ante and ex-post aspects of disaster risk management. Risk awareness remains low in the country; programmes to develop it should be tailored for a variety of audiences, including risk management institutions, the private sector, and the general public.

China and India

China is exposed to all types of disasters and has been one of the most affected countries in recent years. Droughts occur somewhere in China most years, but affected regions vary. Many of China’s largest cities are highly exposed to earthquake risk, with western China experiencing the most severe impact. The eastern seaboard faces most of the country's exposure to typhoons, while landslides are most common in mountainous and hilly areas. Rapid urbanisation of high-risk areas is increasing human and economic exposure. China’s disaster risk management approach began shifting from reactive to proactive in 1998, but challenges remain in regulation, financing, international co‑operation, data collection, risk assessment and emergency response, and low coverage of disaster insurance. The development of comprehensive legislation on disaster risk management could help streamline efforts to overcome challenges.

India is exposed to floods, droughts, heatwaves, cyclones, landslides, tsunamis and wildfires. Floods are most frequent in the basins of the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, droughts are becoming more common in southern areas significant to agriculture, and coastal populations are most affected by cyclones. Current disaster risk management strategies remain focused mostly on response. Moreover, despite rapid urbanisation, urban disaster risk management receives little attention. Co-operation needs improvement, as gaps exist between national policy measures and local implementation. Flood management is particularly hampered by these issues. Financing challenges could be addressed via disaster risk layering, risk transfer and the fostering of public-private partnerships. CAT bonds for severe disasters, would reduce dependence on budget reallocation.

References

[1] CRED (2024), EM-DAT, The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be (accessed on 24 April 2024).

[5] Li, G. et al. (2022), “Mental health and psychosocial interventions to limit the adverse psychological effects of disasters and emergencies in China: A scoping review”, The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific, pp. 100580, Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100580.

[4] Molnar-Tanaka, K. and S. Surminski (2024), “Nature-based solutions for flood management in Asia and the Pacific”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 351, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f4c7bcbe-en.

[3] OECD (2024), Fostering Catastrophe Bond Markets in Asia and the Pacific, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ab1e49ef-en.

[2] Swiss Re (2022), World insurance: Inflation risks front and centre, https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2022-04.html.

Note

← 1. Emerging Asia includes the ten member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) – Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam – plus China and India.