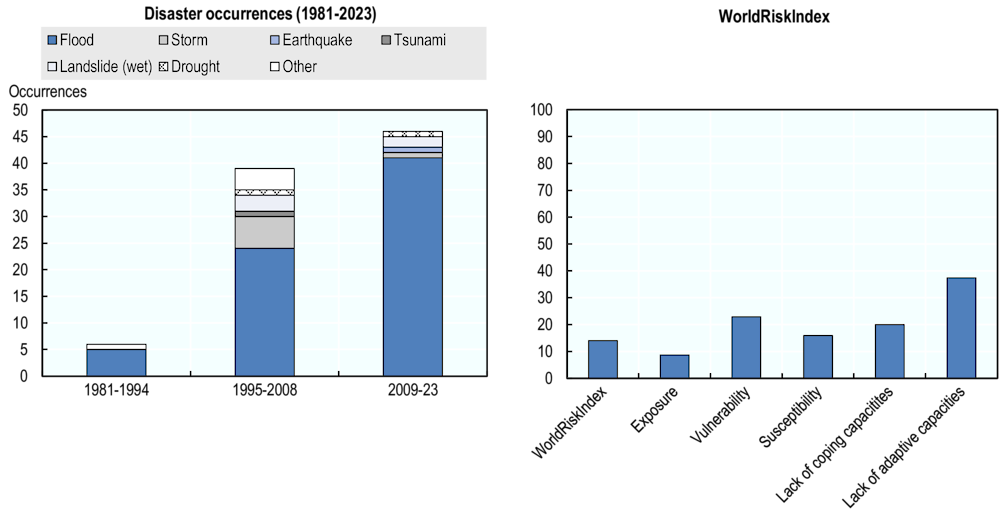

Malaysia is primarily exposed to floods, droughts, landslides, severe haze episodes associated with fires, and tsunamis (Chan, 2015[1]). It is classified as facing the 36th-highest disaster risk by the WorldRiskIndex 2023. The country lies close to the equator and beyond from the Pacific Ring of Fire, leaving it relatively less exposed to both tropical storms and hazards associated with geotectonic risks (earthquakes and volcanic eruptions) than other countries within that region (Chan, 2015[1]; Mohamed Shaluf and Ahmadun, 2006[2]). However, smaller earthquakes and storms do occur and have the potential to cause damage. Between 2000 and 2022, 74 disasters triggered by natural hazards led to almost 500 deaths, affected more than 3.3 million people and caused USD 4.3 billion in economic damage (CRED, 2024[3]).

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2024

Malaysia

Introduction

Malaysia: Disaster occurrences (from 1981 to 2023) and WorldRiskIndex

The hazardscape

Floods are the most frequent and impactful disasters in Malaysia. Seasonal floods can occur during most of the year due to the northeast or southwest monsoon seasons, and flood risk is especially high in low-lying riverine areas and coastal flatlands (Chan, 2015[1]; Izumi, 2019[4]). Floods also account for the majority of disaster losses. Between 2000 and 2022, floods caused estimated damage of approximately USD 2.9 billion and more than half of total disaster mortality (CRED, 2024[3]). The severe floods of 2014, one of the worst hydrometeorological disasters on record in Malaysia, affected 230 000 people and caused economic losses of more than USD 350 million (CRED, 2024[3]). This flood event also impacted more than 13 000 small and medium enterprises (SMEs), caused a significant reduction in palm oil production (a major export crop), and reduced the following year’s GDP by an estimated 0.5% (Auzzir, Haigh and Amaratunga, 2018[5]). The major floods of 2021 led to 56 deaths and caused economic losses of more than USD 1.5 billion (CRED, 2024[3]).

Floods mainly affect agriculture, but they also impact other economic sectors, including manufacturing (through their impact on infrastructure) and mining (Shaari, Karim and Hasan-Basri, 2016[6]; 2017[7]). Malaysia’s SMEs are also highly impacted by floods, with 34% of surveyed SMEs reporting that they had experienced flood impacts in a five-year timespan (Auzzir, Haigh and Amaratunga, 2018[5]).

Malaysia experiences frequent landslides due to its mountainous terrain and frequent rainfall (Nor Diana et al., 2021[8]; Chan, 2015[1]; Izumi, 2019[4]). Majid, Taha and Selamat (2020[9]) identified 21 000 landslide-prone areas, of which 76% are located in peninsular Malaysia. However, the factors affecting landslide occurrence also relate to human activity and especially development in hilly areas, at times characterised by poor slope and building site management (Majid, Taha and Selamat, 2020[9]; Rahman and Mapjabil, 2017[10]). Landslides in Malaysia lead to fatalities, property damages and disruption of transportation networks (Izumi, 2019[4]). Between 1973 and 2011, landslides caused more than 600 deaths and inflicted economic losses of more than USD 1 billion (Abdullah, 2013[11]). Between 2015 and 2019, 86 landslides with considerable social and economic impact were reported in the state of Selangor alone (Izumi, 2019[4]). With many low-lying areas developed during rapid economic growth since the 1980s, meeting the high demand for new development has increasingly been achieved by building on sloping or hilly terrain, affecting landslide risk directly by removing forest cover and increasing exposure (Izumi, 2019[4]; Majid, Taha and Selamat, 2020[9]).

Malaysia is also vulnerable to droughts, with frequent short-term droughts in most regions as well as severe drought episodes with the potential to affect the entire country (Hasan et al., 2021[12]; WMO, 2014[13]). High drought frequency and severity is observed especially in the northeast and southeast regions of peninsular Malaysia (Hasan et al., 2021[12]). Prolonged drought conditions in peninsular Malaysia have in recent years been increasing in frequency, with further increases in frequency projected for the western region, putting water resources and the agricultural sector under severe pressure (Hui-Mean et al., 2019[14]; Zin, Jemain and Ibrahim, 2012[15]). Drought impacts in Malaysia include reduced productivity in agriculture and aquaculture, reduced freshwater supply for consumption and adverse effects on the industrial sector (World Bank and ADB, 2021[16]). For example, the drought in 2014 adversely affected more than 8 000 paddy farmers and caused crop losses of around USD 22 million (Tan et al., 2017[17]). Drought conditions also contribute to the risk of wildfires, with more than 7 000 bush and forest fires reported during the 2014 drought (WMO, 2014[13]).

Climate change perspective

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of floods, droughts and heatwaves through changes in temperature and precipitation patterns (World Bank and ADB, 2021[16]). Flood risk has been increasing over the last 40 years due to intensifying rainfall associated with climate change. The frequency and intensity of flood events are expected to increase with future warming, with rainfall projected to increase especially in the east of the country (World Bank and ADB, 2021[16]). Future sea level rise is expected to exacerbate coastal hazards, with some sections of the Malaysian coastline also expected to face increased and previously unseen storm surges due to a southward shift in cyclone paths (Wood et al., 2023[18]).

Malaysia has a large coastal population potentially exposed to future sea level rise and to coastal hazards such as storm surges and tsunamis. As much as 60% of the country’s population occupies the coastal regions, and this is also where most SMEs are located (Azimi, Syed Zakaria and Majid, 2019[19]). Malaysia is also characterised by very high flood exposure, with 90% of nighttime lights (a proxy for the concentration of economic activity) estimated to be in areas exposed to floods (Chantarat and Raschky, 2020[20]).

Disaster vulnerability in Malaysia is shaped by factors such as rapid urbanisation and ecosystem degradation driven by high growth. Rapid urbanisation has contributed to flood risk through increased population density, land use change, obstructions to water flow and drainage, and reduction of natural buffer zones due to deforestation (Chan, 2015[1]; Izumi, 2019[4]). While poverty has been decreasing rapidly in recent decades, pockets of poverty remain. Poverty is more prevalent in rural regions such as Northern Kelantan or Hulu Terengganu. Rural to urban migration is also increasing the number of urban poor, increasing urban vulnerability in some locations.

Challenges for disaster risk management policy

The 4th National Physical Plan (NPP-4), issued in 2021 and covering the years 2021-25, explicitly mention implementing disaster risk mitigation as a strategy (Economic Planning Unit Malaysia, 2022[21]). The government should develop a flood-related policy to establish the duties of various stakeholders including the government, non-governmental organisations and the public (Ridzuan et al., 2022[22]) consistent with a target objective of NPP-4. Other priorities include designing and implementing policies for coastal land use, regulating development in landslide-prone areas and improving disaster preparedness and resilience (Economic Planning Unit Malaysia, 2022[21]). However, Malaysia lacks a legislative framework to integrate flood management policies and mechanisms with broader policy objectives (Ridzuan et al., 2022[22]; UNDRR, 2020[23]). Many of Malaysia’s disaster risk management processes currently involve reactive rather than proactive approaches and lack a long-term planning perspective (Chong and Kamarudin, 2018[24]; Ridzuan et al., 2022[22]). Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on disaster preparedness and prevention. The integration of disaster risk management considerations into sectoral development policies is also limited (UNDRR, 2020[23]). Climate change adaptation should also be more strongly integrated with disaster risk reduction efforts (Madnor, Harun and Ros, 2024[25]).

As for disaster financing, disaster-related budget measures need to be strengthened, and disaster risk management would benefit from disaster financing being expanded into budgeting at all levels (Rosmadi et al., 2023[26]; UNDRR, 2020[23]). At the local level, the country faces shortages of both human and financial capital to enable effective implementation of disaster risk management policies. Therefore, investments to increase local-level disaster risk management capacity are required (Rosmadi et al., 2023[26]).

The use of ex-ante financing mechanisms such as disaster insurance should be expanded. Implementation of agricultural insurance is constrained by factors such as lack of insurer experience, lack of required data, limited financial capacity and high administrative costs. To enable disaster insurance implementation, the possibility of a public-private partnership should be explored to assist the market and design appropriate insurance products (Alam et al., 2020[27]).

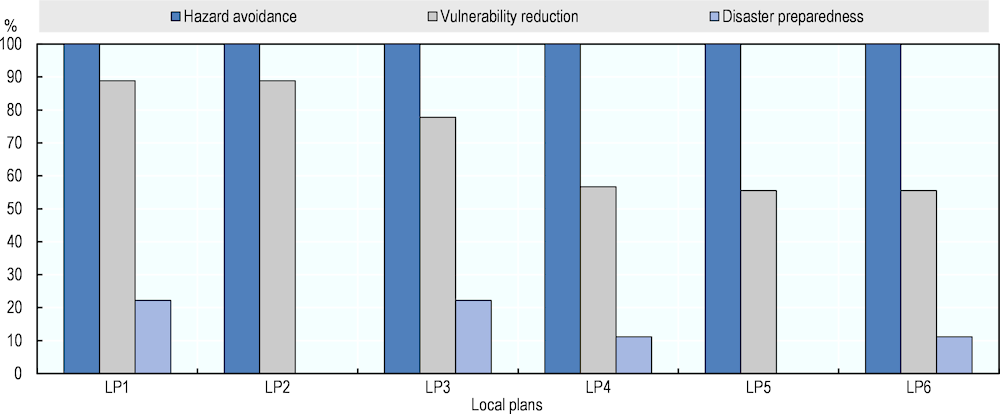

Disaster risk reduction measures need to be better incorporated into local-level planning and zoning, especially as regards disaster preparedness (Norizan, Hassan and Yusoff, 2021[28]; Majid, Taha and Selamat, 2020[9]; Ridzuan et al., 2022[22]). Other obstacles limiting disaster risk management efforts, as well as progress in resilient development more broadly, include non-compliance with suitable urban development plans and guidelines, a lack of data for detailed risk assessments at the local level and a lack of support and commitment from the local authorities (Mohamad Amin and Hashim, 2014[29]).

Percentage of flood risk reduction dimensions integrated in local plans

Source: (Norizan, Hassan and Yusoff, 2021[28]), “Strengthening flood resilient development in Malaysia through integration of flood risk reduction measures in local plans”, Land Use Policy, 102, 105178.

For flood risk management, greater emphasis could be placed on preparation strategies and adaptation measures reducing vulnerability (Norizan, Hassan and Yusoff, 2021[28]). These efforts could include stricter enforcement of standard operating procedures and disaster-related laws, increasing asset inspection and maintenance, conducting awareness campaigns and community activities to enhance community awareness and foster community involvement with local agencies, and enhancing the influence and jurisdiction of some relevant flood management agencies (Rosmadi et al., 2023[26]). For the Sarawak region, for instance, the flood risk management challenges were described to include upgrading the drainage systems, strengthening of flood forecasting and early warning systems, and enhancing public awareness and collaboration among government agencies (Muzamil et al., 2022[30]).

References

[11] Abdullah, C. (2013), “Landslide risk management in Malaysia”, WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Disaster Management and Human Health Risk III, https://doi.org/10.2495/dman130231.

[27] Alam, A. et al. (2020), “Agriculture insurance for disaster risk reduction: A case study of Malaysia”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Vol. 47, p. 101626, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101626.

[1] Aldrich, D., S. Oum and Y. Sawada (eds.) (2015), Impacts of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods, Springer Japan, Tokyo, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55022-8.

[5] Auzzir, Z., R. Haigh and D. Amaratunga (2018), “Impacts of Disaster to SMEs in Malaysia”, Procedia Engineering, Vol. 212, pp. 1131-1138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.146.

[19] Azimi, M., S. Syed Zakaria and T. Majid (2019), “Disaster risks from economic perspective: Malaysian scenario”, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 244, p. 012009, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/244/1/012009.

[20] Chantarat, S. and P. Raschky (2020), Natural Disaster Risk Financing and Transfer in ASEAN Countries, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.198.

[24] Chong, N. and K. Kamarudin (2018), “Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges from the Perspective of Agencies”, Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, Vol. 16/1, pp. 105-117, https://doi.org/10.21837/pmjournal.v16.i5.415.

[3] CRED (2024), EM-DAT, The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be (accessed on 12 December 2023).

[21] Economic Planning Unit Malaysia (2022), 4th National Physical Plan: The Planning Agenda for Prosperous, Resilient and Liveable Malaysia, https://rmke12.ekonomi.gov.my/ksp/storage/event/962_22_dr_alias_rameli_4th_national_physical_plan_for_a_prosperous_resilient_and_liveable_malaysia.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2022).

[12] Hasan, H. et al. (2021), Hydrological Drought across Peninsular Malaysia: Implication of Drought Index, Copernicus GmbH, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2021-249.

[14] Hui-Mean, F. et al. (2019), “Trivariate copula in drought analysis: a case study in peninsular Malaysia”, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, Vol. 138/1-2, pp. 657-671, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-019-02847-3.

[4] Izumi, T. (2019), Disaster Risk Report: Understanding Landslides and Flood Risks for Science-Based Disaster Risk Reduction in the State of Selangor, https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/disaster-risk-report-understanding-landslides-and-flood-risks-science-based-disaster.

[25] Madnor, M., A. Harun and F. Ros (2024), “Integrating adaptation of climate change to strengthen Malaysia’s disaster risk governance”, Environment and Social Psychology, Vol. 9/4, https://doi.org/10.54517/esp.v9i4.2189.

[9] Majid, N., M. Taha and S. Selamat (2020), “Historical landslide events in Malaysia 1993-2019”, Indian Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 13/33, pp. 3387-3399, https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/v13i33.884.

[29] Mohamad Amin, I. and H. Hashim (2014), “Disaster Risk Reduction in Malaysian Urban Planning”, Planning Malaysia, Vol. 12, https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v12i4.124.

[2] Mohamed Shaluf, I. and F. Ahmadun (2006), “Disaster types in Malaysia: an overview”, Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, Vol. 15/2, pp. 286-298, https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560610659838.

[30] Muzamil, S. et al. (2022), “Proposed Framework for the Flood Disaster Management Cycle in Malaysia”, Sustainability, Vol. 14/7, p. 4088, https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074088.

[8] Nor Diana, M. et al. (2021), “Social Vulnerability Assessment for Landslide Hazards in Malaysia: A Systematic Review Study”, Land, Vol. 10/3, p. 315, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030315.

[28] Norizan, N., N. Hassan and M. Yusoff (2021), “Strengthening flood resilient development in malaysia through integration of flood risk reduction measures in local plans”, Land Use Policy, Vol. 102, p. 105178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105178.

[10] Rahman, H. and J. Mapjabil (2017), “Landslides disaster in Malaysia: An overview”, Health & the Environment, Vol. 8/1, pp. 58-71, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321096764_Landslides_Disaster_in_Malaysia_an_Overview.

[22] Ridzuan, M. et al. (2022), “An Analysis of Malaysian Public Policy in Disaster Risk Reduction: An Endeavour of Mitigating the Impacts of Flood in Malaysia”, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, Vol. 12/7, https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v12-i7/14247.

[26] Rosmadi, H. et al. (2023), “Reviewing Challenges of Flood Risk Management in Malaysia”, Water, Vol. 15/13, p. 2390, https://doi.org/10.3390/w15132390.

[7] Shaari, M., M. Karim and B. Hasan-Basri (2017), “Does Flood Disaster Lessen GDP Growth? Evidence from Malaysia’s Manufacturing and Agricultural Sectors”, Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies, Vol. 54/1, pp. 61-81, https://doi.org/10.22452/mjes.vol54no1.4.

[6] Shaari, M., M. Karim and B. Hasan-Basri (2016), “Flood disaster and mining sector GDP growth: The case of Malaysia”, International Journal of Management Sciences, Vol. 6/11, pp. 544-553, https://ideas.repec.org/a/rss/jnljms/v6i11p4.html.

[17] Tan, M. et al. (2017), “Evaluation of TRMM Product for Monitoring Drought in the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia”, Water, Vol. 9/1, p. 57, https://doi.org/10.3390/w9010057.

[23] UNDRR (2020), Disaster Risk Reduction in Malaysia: Status report, United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, https://www.undrr.org/publication/disaster-risk-reduction-malaysia-status-report-2020.

[13] WMO (2014), Capacity development to support national drought management policy, https://www.droughtmanagement.info/literature/UNW-DPC_NDMP_Country_Report_Malaysia_2014.pdf.

[18] Wood, M. et al. (2023), “Climate-induced storminess forces major increases in future storm surge hazard in the South China Sea region”, Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, Vol. 23/7, pp. 2475-2504, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-23-2475-2023.

[16] World Bank and ADB (2021), Climate Risk Country Profile: Malaysia, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/15868-WB_Malaysia%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf.

[15] Zin, W., A. Jemain and K. Ibrahim (2012), “Analysis of drought condition and risk in Peninsular Malaysia using Standardised Precipitation Index”, Theoretical and Applied Climatology, Vol. 111/3-4, pp. 559-568, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-012-0682-2.