Until recently, Kazakhstan has approached the subject of economic regulation of WSS from an “anti-monopoly” perspective. Despite being a government agency, the Committee on Regulation of Natural Monopolies and Protection of Competition under the Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan (KREMZK) is a large organisation with many regional branches. Among others, it monitors and interferes in industry accordance to the Law on Competition. It seeks to control, if not prevent, industry dominance. WSS operators, being natural monopolies, are dominant players by definition. WSS operators turn to KREMZK with a tariff application.

Tariff applications are based on a methodology set by KREMZK. The process shows a number of similarities with the Moldovan situation. The tariff application process takes a long time; it involves furnishing numerous data; the methodology is in some respects ambiguous; and the methodology and the way it is applied puts a large administrative burden on WSS operators.

As part of a broad economic reform programme, the government of Kazakhstan also intends to reform the tariff-setting process and the regulatory framework for WSS operators, district heating, seaports and airports. An interesting aspect of this process is the strong collaboration with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Based on the government’s request, the EBRD has arranged, or is arranging, for an array of Technical Assistance (TA) projects to facilitate this reform. TA takes place at pan-sectoral level with respect to the overall reform of economic regulation, as well as to individual sectors, such as water, heating, electricity, seaports and airports.

With respect to WSS, this TA involves development of a new tariff policy, the elaboration of a detailed methodology and the testing of that methodology in a pilot utility.

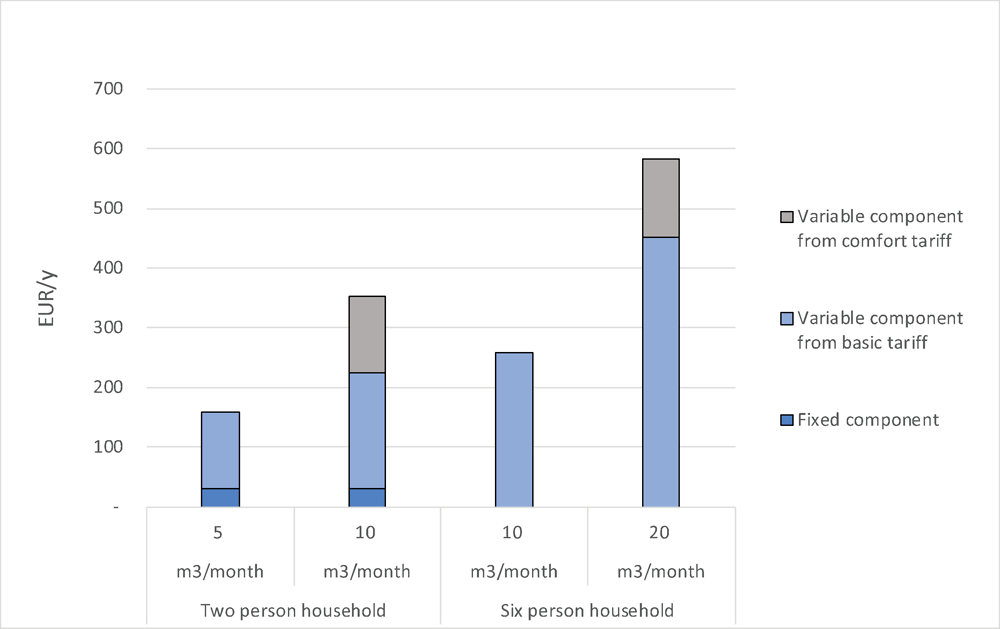

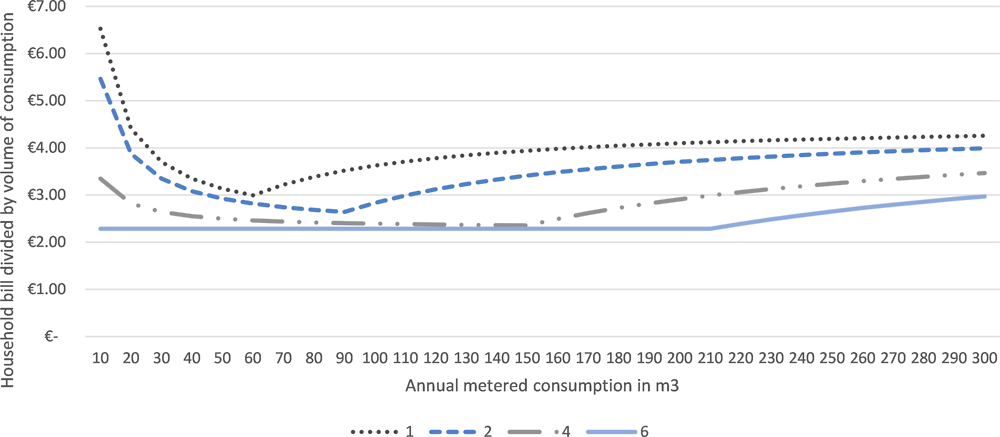

A separate project has been launched to elaborate and pilot social measures. Social measures are mostly administered through the housing subsidy system in a way similar to the Russian Federation and Ukraine. These systems aim to cap household utility expenses to a maximum percentage of income, based on a complex reimbursement procedure. A permanent stream of documentary evidence is required to remain eligible for payments. Furthermore, one must prove payment to the utility for amounts not paid to the utility by the housing payment system. Also, in the case of Kazakhstan, the eligibility criteria and the system of subsidy rates are complex and costly to administer for both recipient and subsidy provider. With respect to social measures, the government of Kazakhstan seeks to at least streamline the mechanism, if not to overhaul it entirely (OECD, 2016[8]).

With respect to the reform of the ERS for WSS, the government of Kazakhstan will continue to regulate WSS alongside other sectors within an overall framework. The specific framework may be close to or similar to the one for district heating. These sectors will now be approached as one that naturally need regulation, following from their natural monopoly status. This perspective looks more appropriate than the pure anti-monopoly stance.

Technically, the reforms will lead to a regulatory asset base (RAB) and weighted average costs of capital (WACC) that are better and more appropriately defined. Both items determine an important component of the eligible tariff. The RAB determines the amount of depreciation that may go into the tariff calculation. The WACC determines the cost of capital of the RAB and hence the amount of free cash flow for investment that a utility can build into its tariff.

The reforms are likely to lead to a more business and performance-oriented regulator rather than one based on sometimes inappropriate norms and ambiguous standards. The future economic regulator is likely to be leaner, more oriented to the business plan and its Key Performance Indicators. It will also likely focus on incentivising performance improvement over time. Furthermore, it shall be more aware of its own regulatory impact and the administrative burden placed on its subjects. The involvement of EBRD may suggest that the new regulatory framework will accommodate strong lending to a sector that currently lacks creditworthiness.

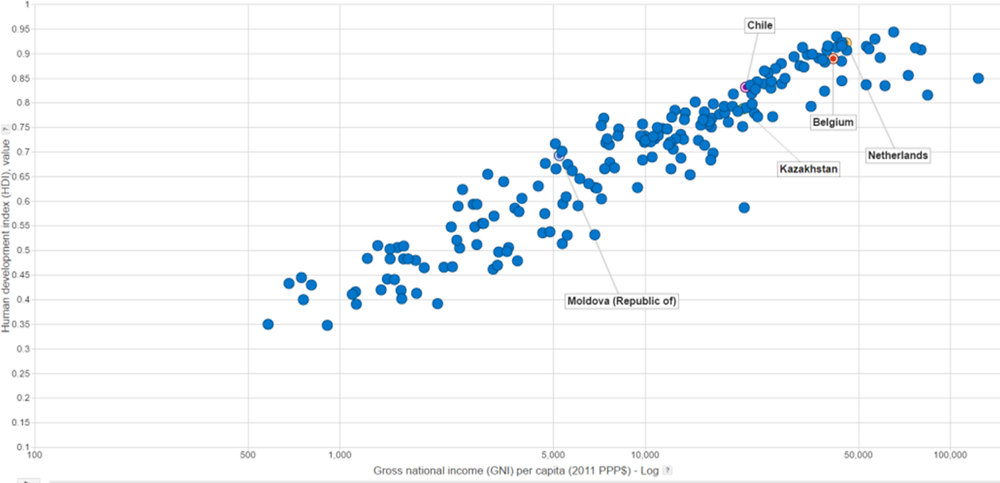

The new regulatory framework will be responsive to the interest of lenders, rather than the short-term interest of consumers in terms of low tariffs. Currently, tariffs in Kazakhstan are on average half those in Moldova, though many provinces of Kazakhstan are not less water-stressed than Moldova. In the longer term, however, poor and rich customers alike will be much better off with rehabilitated and extended networks, wastewater treatment, improved customer service, etc. That requires that the ERS also addresses financing the WSS sector.

Yet Kazakhstan is by no means unique in designing ERS reform in collaboration with an IFI. In Romania, the EBRD has also played an active role for many years. Kazakhstan provides a relevant reference because the starting point of its ERS shows a number of similarities to the Moldovan ERS and because it is also a former Soviet Union state. The organisation of the ERS reform in Kazakhstan may inspire Moldova where it is only just beginning. It shows how a country in 2017 with similar reform challenges can go about this process.