This chapter provides a set of recommendations on establishing a sound economic regulatory system for water supply and sanitation in the Republic of Moldova. They are based on analysis in previous chapters of this report and consider proceedings from the Expert Meeting and the National Policy Dialogue (NPD) Co‑ordination Council meeting in November 2016. It outlines an indicative implementation plan, with references to Annexes for further information. Finally, it makes a wide range of recommendations, including ones with respect to institutional set up, facilitating performance improvement, regionalisation, business models, tariffs, the use of economic instruments, access to finance and social measures. Implementation of the proposed recommendations is discussed at the end of the chapter.

Enhancing the Economic Regulatory System for Moldova’s Water Supply and Sanitation

Chapter 4. Recommendations and conclusions

Abstract

Reform objectives and lead institution

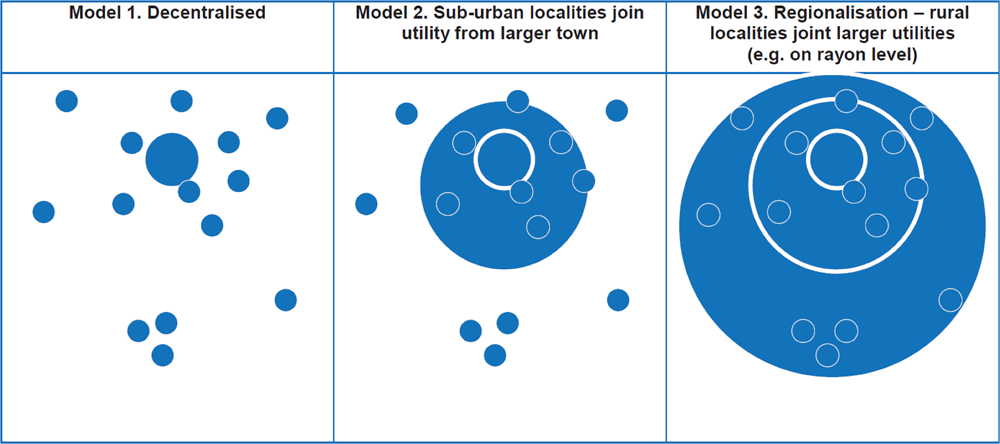

The following seven objectives for an economic regulatory system (ERS) in water supply and sanitation (WSS) have been formulated:

1. A tariff (structure and level) that gives incentives to perform better.

2. More decisive regionalisation of WSS services.

3. The nurturing of sustainable business models, not least for regionalised WSS services.

4. An optimal mix of taxes, tariffs and transfers (the “3Ts”), based on an up-to-date national WSS strategy.

5. Improved use of economic instruments to achieve set WSS policy objectives.

6. Wider use of external finance to bridge the projected funding gap.

7. Well-targeted WSS-related social protection measures.

Figure 4.1 on the next page provides further detail of what can be associated with these objectives. Agreement on the objectives among stakeholders opens the door for implementing the 20 recommendations for comprehensive reform. Over several years, implementation would radically change the evaluation of the ERS in section 2.5. The following sections each elaborate an individual recommendation. Section 4.1 provides summary tables and an indicative implementation framework. Upon adoption of the reform package, a more detailed blueprint must be elaborated to control the processes.

Recommendation 1. Re-establish the WSS Commission to lead and steer the reform.

Re-establishing the WSS Commission is considered a key enabler for progressing on each of the objectives and recommendations. So far, the lack of high-level policy co‑ordination has been the main obstacle to policy development and implementation. The re-establishment of the WSS Commission does not guarantee co‑ordination; it is only an instrument. If it has a well-scoped mandate with high-level ownership, it can be effective. The WSS Commission is seen as a champion and key instrument for ERS reform. The Commission would meet as often as is necessary, operating formally under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister. In practice, the Commission is operated by one or more dedicated professionals without ministerial or explicit political affiliation. The WSS Commission can provide for better co‑ordination as it has more leverage over other institutions than the Ministry of Environment (MoE). At the same time, however, it monitors the MoE and other institutions so that agreed water sector reform measures are indeed implemented. Among many other tasks, the WSS Commission may also continue to push for revision of the design and construction standards for WSS projects.

Figure 4.1. Objectives and the associated achievements

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Providing incentives towards performance improvement

The role of the economic regulator

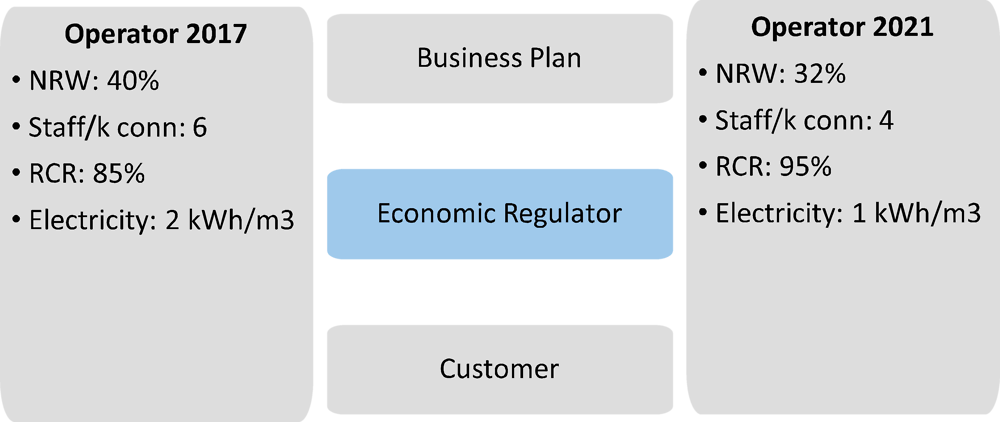

Section 2.3 of this report identifies several difficulties with the tariff methodology and its application by the economic regulator. The complexity of the tariff-setting process overshadows the basic aim of the tariff i.e. to provide incentives for efficient and economic use of resources by both operator and consumer.

Recommendation 2. Recognise the independence of the economic regulator in line with international best practice.

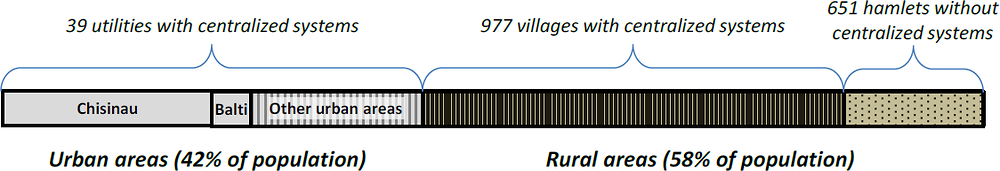

The economic regulator shall be perceived as a broker in the centre of a positive sum game where both customer and operator can win from future efficiency gains. The independent economic regulator has some discretion in the allocation of the incentives. It can give incentives to the customer to save more water or to the operator to operate more efficiently. A fair mixture of these incentives is needed. This concept is illustrated in Figure 4.2. Starting from the current situation, the operator offers a certain efficiency increase that is backed up by its business plan. The regulator reviews whether this is affordable and feasible.

Figure 4.2. Economic regulator in the centre of the allocation of incentives

Source: Author's own elaboration.

The role of the business plan

How the proceeds of the efficiency gains are distributed is of secondary importance. Eventually, the regulator can ensure that all gains accrue to the customer through lower tariff, improved access or better service. Realising the performance improvements comes first. Once realised, the new efficiency level will be the starting point in the next regulatory cycle. With time, all performance improvement gains can accrue to the customer. Operators need financial leeway and autonomy to realise those improvements. Sometimes it requires investments, which can only pay off over time. Skilful managers will proceed quicker and be more innovative than less skilful ones. Assessing performance improvement potential is therefore much more a business exercise than an accounting one. It is more art than science.

Therefore, the regulator assesses the business plan (or equivalent such as corporate development plan, Financial and Operational Performance Improvement Programme or action plan) as the main document. Absence of a business plan hints at a lack of purpose and at operating in a “business as usual” manner. Explicit targets and clear plans identify operators that are developing their business. Once given the responsibility, the regulator needs capacity to review and act on the findings. For instance, the regulator can publish performance data and use peer pressure as a tool.

Recommendation 3. Require and analyse business plans from operators.

Both municipalities and the economic regulator can require and analyse business plans from operators.

From larger operators one can expect more detailed and higher quality planning. Smaller companies may need to be furnished with a template for a simplified business plan. Such a template can be filled easier and gives a better focus to managers who are perhaps inexperienced in this field.

Recommendation 4. Provide a template business plan and MS Excel model template for projections.

The regulator should provide a template business plan, as well as an MS Excel model template for projections. An outline for this template and model has been attached in Annex B. Note that the computer-based Financial Planning Tool for Water Utilities developed by the OECD could support the business plan with financial projections.

Metering differences

In urban water supply, the biggest concern of customers is the large amount of “metering differences” they face (see section 4.3) i.e. the difference between the metered supply to the apartment block at the entry and the sum of readings of the individual apartment meters inside the building. The point of transfer shall remain for all customers the inlet to the building (apartment block). This holds for individual houses, as well as for apartment blocks. Direct contracts with end users need not change how these metering difference losses are distributed among consumers.

In theory, one can ask the operator to control internal plumbing, but the service would come at a price. This service is not a natural monopoly and is typically non-regulated; third parties could take on the task. If the service is covered within the overall tariff, it would be notoriously difficult to add an adequate price tag on this service and to control for its execution. This, however, is the approach of the present tariff methodology in the Republic of Moldova (hereafter “Moldova”).

Recommendation 5: Give incentives to property owners to resolve internal leakages.

Property owners should receive incentives to resolve internal leakages. This would entail calculating and applying a uniform tariff for a single cubic metre of water that is delivered to any property (house or condominium). Elaboration, negotiation and regulation are needed to determine in which way and according to what distribution key the metering differences shall be charged upon individual contractors (end users):

Metering differences may be invoiced by the operator to the entity managing the building.

Metering differences may be directly invoiced to the apartment owners as an additional separate line item on the water bill, according to a specific distribution key. This key may differ according to circumstances (see section 4.3) or be stipulated by the economic regulator as needed.

The leading principle shall be that payment is due for all cubic metres of water that have entered the private property.

Deciding who pays for the metering differences

Customers from condominiums are concerned first about the amount of “metering differences” and the way this charge is passed on to customers. In urban water supply, the vast majority of water is supplied to apartment blocks or condominiums.

What are metering differences?

Metering differences occur when the volume of water that enters the block exceeds the sum of the volume billed to individual apartments. The volume billed to individual apartments can be based on metering or on a notional consumption volume in the absence thereof.

Individual condominiums are private property, but ownership of the building is collective. Therefore, management is separated from ownership. It is carried out by a range of bodies such as municipal management companies, associations, private enterprises, etc.

The legislation and institutions for the collective property of the building must allow for its proper management and maintenance. Too often, the collective part of the properties is allowed to deteriorate. That includes the internal plumbing.

From the perspective of service providers, the point of delivery is the inlet of the water pipes to the building. What happens thereafter in terms of water quality and quantity is up to the owners of the private property. Operators may be required to facilitate individual metering. However, due to the design of the plumbing (of the indoor water distribution pipes), individual metering often requires more than one meter per household.

Ultimately, however, operators should be entitled to compensation for the full amount of water that has entered the private property and hence for the associated service provided.

What are the causes of metering differences?

There are a number of possible causes. There may be losses through the collectively owned pipes and connections. Individual apartment meters may be old or of poor quality and hence underreport true consumption. Such meters may fail to register small amounts of permanent consumption, such as through small leakages. There may be tampering with the meter or bypasses. In theory, there may also be inaccurate metering at the inlet to the apartment block. Customers that are not metered may consume more than the notional amount (“consumption norm”) that is invoiced to them for direct consumption. All these causes are more likely to occur in older, less well-maintained buildings than in newer, modern blocks.

One solution is to invoice any metering difference directly to the condominium or the entity managing the apartment block. The entity could then pay and seek reimbursement from the apartment owners. This is the practice for collective electricity used for lighting, lifts, and cleaning and maintenance costs.

Operators also may be required to develop sophisticated systems to allocate any metering differences according to a certain distribution key (rule) among apartment owners. In this way, individual apartment owners receive a bill for consumption of two services:

a. direct consumption of water and wastewater services in this apartment

b. fair share of the collective water and wastewater service (allocated according to direct consumption, surface of the apartment, number of inhabitants, etc.)

Presently customers in Chisinau, for instance, receive the second type of service based on their direct consumption. This leads to frustration as honest customers pay both for their full amount of consumption and on top of that, consequently, a disproportional part of the metering differences.

Is individual contracting a solution?

Billing, ownership and supply relationship are separate concepts. At present, individuals are billed based on collective contracts. The move to individual contracts where feasible might be a welcome development. But it does not resolve the question of the metering differences. Even when there are individual contracts with owners of apartments, the supply remains up to the private property i.e. the block meter.

What is the effect of extending the responsibility for supply up to the apartment?

WSS operators do not have the legal, operational, staff and financial capacity to take responsibility for in-house plumbing. Another question is location of the new delivery point. The responsibility and costs for water losses are currently located at block level. Admittedly, block management does not always take care of this responsibility. There are many issues in relation to access, metering, maintenance, etc. But making the operator responsible further for internal networks only aggravates the problem. In fact, no one will be responsible and everyone will pay the price. It is therefore much better to maintain a strong incentive on blocks to improve internal organisation, metering and maintenance, and to discover fraudulent behaviour.

What is the effect of making the collective owners firmly responsible?

If a community in a condominium decides to get rid of the losses, because the benefits will outweigh associated costs, then it can do the following:

1. Establish the necessary institutions to make this collective choice. This may require establishing an authorisation system, representation, council or other institution.

2. Attract the funding, either through own financing, loan or grant. The funding may be attracted collectively or individually and subsequently pooled.

3. Assign someone to carry out maintenance and/or replace the meters. This may be the WSS operator, but it may be any qualified third party as well.

4. Reap the benefits of a smaller amount of metering losses that need to be paid.

When tariffs go up, the benefits will increasingly outweigh the costs. But challenges remain such as representation, decision making, access to finance and administration. National authorities can support the process by providing template documents. Municipalities can support with help desks and granting schemes. Financial institutions can apply for special credit lines with international financial institutions to fund projects aimed at saving water and energy. These measures would make sense only if the following conditions apply:

1. Water services are priced at the full costs of service.

2. Blocks are invoiced for the full volume of the service.

3. Payment is enforced.

Such a change in approach associated with the previous three recommendations is ultimately incompatible with the present tariff methodology. Too much of the tariff methodology has already been determined directly by Law 303 on Water Supply and Sanitation. This is not a desirable situation.

Recommendation 6: Amend Law 303, confining it to tariff-setting principles, and subsequently work out these principles in the new tariff methodology.

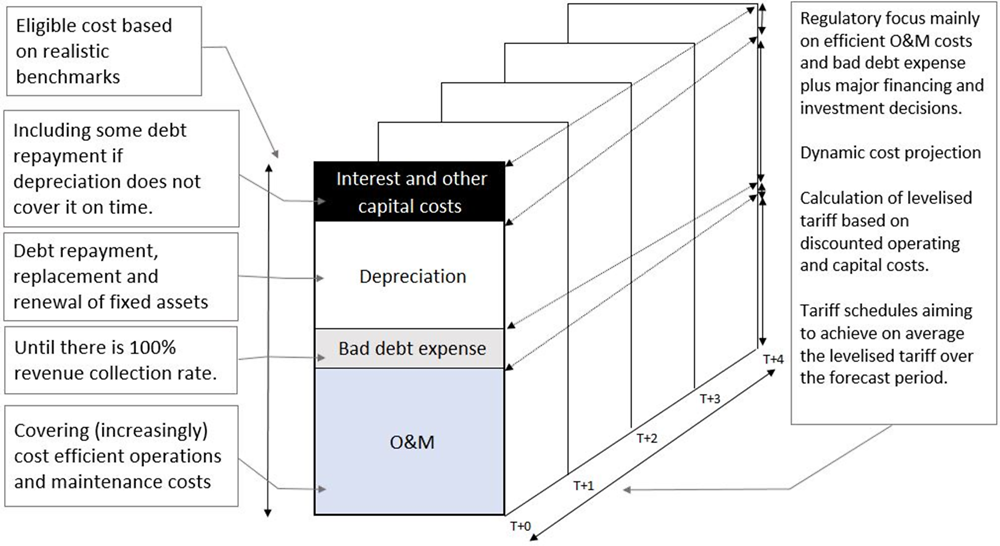

This approach will allow for more flexibility and discretion on the side of the independent economic regulator. The objective shall be to focus on the dynamics (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Dynamic approach to tariff setting

Source: Author's own elaboration

Recommendation 7: Adopt a dynamic tariff-setting methodology.

Dynamic tariff setting would discount future operating and capital outflows and calculate a levelised tariff. This is like an average cost-recovering tariff over the forecast period. The tariff may rise gradually, aiming to equal on average the levelised tariff over the forecast period. This approach breaks with the static costs base method and anticipates future developments, including regionalisation of WSS services and investments. It will allow for transition periods in achieving efficiency with respect to staffing, electricity use and non-revenue water (NRW). Currently, those efficiency levels can be inserted only into the base costs. This leaves utilities frequently with performance improvement requirements that are out of touch with reality or with no requirements at all. The former is often the case with respect to NRW, the latter with respect to staff to output ratios.

Meanwhile, however, the existing tariff methodology can be used as a guidance document. The regulator shall just have more discretion in its application. A shift in focus towards Key Performance Indicators and business plans can already be initiated.

Recommendation

Recommendation 8: Increase the discretion of the economic regulator, requiring legal and regulatory amendments, as well as clarifying institutional roles among stakeholders.

Incentives to perform will come from other economic instruments too, rather than from the tariff alone. These are discussed in section 4.7.

Furthermore, transparency and good corporate governance provide incentives. As owners of WSS systems, municipalities play an important role. Headline performance data, such as for NRW, staff per population served/connected, specific electricity consumption and customer service shall be firmly in the public domain.

Reccomentadion 9: Publish an annual performance report, identifying winners and laggards, utilities that catch up and those that fall behind.

The focus of the annual performance report, produced by the economic regulator, shall be on improvement rather than purely on “naming and shaming”. This will allow for lagging operators to change direction and thus create a better basis for future co‑operation.

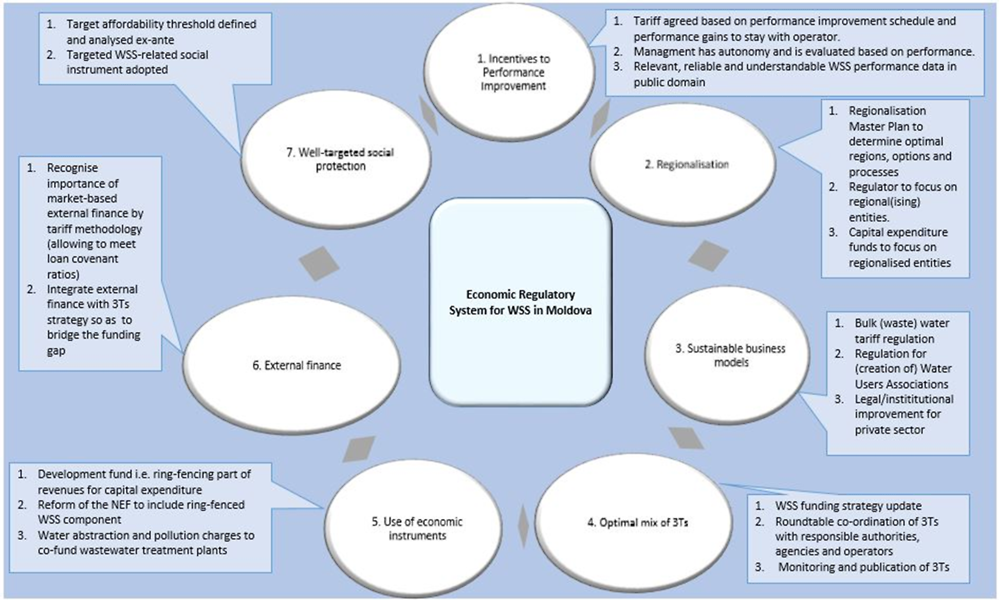

Facilitating the regionalisation of WSS services

Most smaller operators lack the business planning skills to develop business plans, though anyway the economic regulator cannot analyse too many such plans and supervise their implementation. Regionalisation is therefore a condition for an improved ERS. Larger entities can provide for higher quality data and plans, while the economic regulator can better cope with the amount of data, monitoring and auditing needs. There are many more reasons why regionalisation is the cornerstone of the WSS strategy for Moldova, including economies of scale and scope, access to finance and ability to regulate (Tuck et al., 2013).

Decisive progress on regionalisation

Recommendation 10: Proceed more decisively with regionalisation, making it a firm condition for funding capital expenditure.

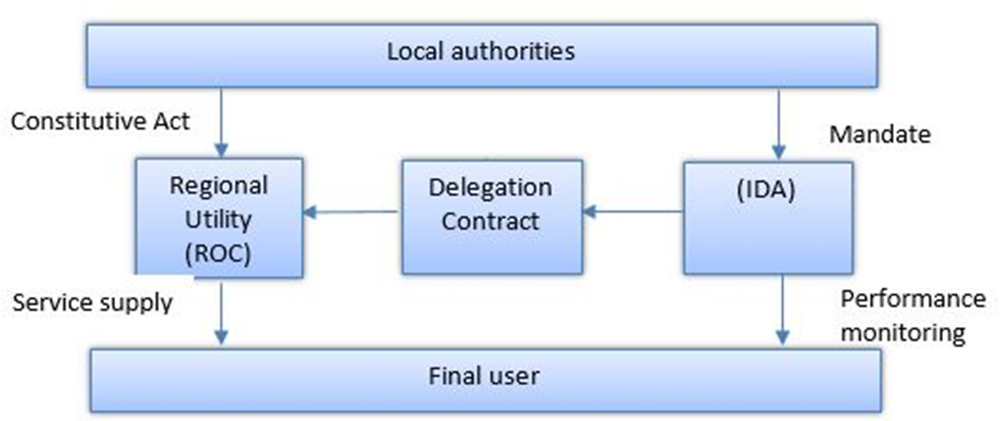

The widely accepted Romanian model of regionalisation is illustrated in Figure 4.4. Over the last few years, it has become clear this is the model stakeholders in Moldova want to develop. Legal amendments can focus on making this model applicable in Moldova. It will remain a challenge, but without regionalisation the WSS sector cannot proceed and the set ambitious development goals cannot be achieved. Each step in any regionalisation process must strike a careful balance between short-term obstacles and risk, and long-term opportunities and benefits. Only by making financial support conditional to progress on the regionalisation process does the government send out a firm signal that it is serious on its own development strategy (ANSRC, 2014[1]).

Figure 4.4. Regionalisation concept based on Romanian model

Source: (ANSRC, 2014[1]), Presentation of National Authority for Public Services of Communal Management of Romania, www.danube-water-program.org/media/dwc_presentations/day_0/Regulators_meeting/2._Cador_Romania_Viena_ANRSC.pdf

The World Bank’s 2013 Water Sector Regionalization Review (Tuck et al., 2013[2]) provided a good ten-year road map, which remains relevant and accurate today. It includes establishment of the Regionalization Task Force, laying the foundations for regionalisation among stakeholders, master planning, institutional structures to be developed, phases in the process, etc. Regional utility may be in public ownership or it can be managed by a private operator (see Annex A for more details).

Recommendation 11: Adopt the approach, road map and timeline set out in the regionalisation review (Tuck et al., 2013[2]).

Transfer of assets

In most transition countries, the exact legal status of WSS assets is slightly ambiguous. At the same time, three things are clear:

1. Assets in use that generate economic benefits must be capitalised and depreciated under International Financial Reporting Standards.

2. Asset stripping is not an option for WSS operators. Most fixed assets in WSS may not be, cannot be and will not be dug up and sold.

3. Most WSS systems in Moldova are in urgent need of rehabilitation.

The exact legal status of the assets is therefore mostly of academic interest. In practice, the WSS operator manages and maintains these assets. Standardised procedures and standard agreements are needed when assets are transferred to an operator. This is recommended not only for regionalisation. There are three cases of transfer of assets and for each of them clear guidelines are required.

1. Extension of the service area

When an operator takes over responsibility for a public network that it previously did not operate, a standardised procedure and a standard agreement is needed on service area extension.

2. Privately-built network handed over to operator

Citizens in rural neighbourhoods regularly invest their own money in the development of a network and intend to hand this over to a professional operator for further use. This shall be possible according to a standard procedure and under a standard agreement.

3. Regionalisation

When a regional operator is established on the basis of two or more existing operators, the assets are put together in a single entity. A standardised procedure and standard agreements shall be developed for this process.

For all three categories, guiding brochures would help stakeholders arrange for their transaction in a clear, legally sound and organised manner. If compensation must be paid, transactions are not likely in any of the cases. That means the law shall make it clear that while such compensation is not forbidden, it is not a requirement either. A recent decision of the Constitutional Court awaits further clarification/jurisprudence.

Recommendation 12: The Ministry of Regional Development and Construction in co‑operation with water agency Apele Moldovei should provide practical support towards the regionalisation process.

The Ministry of Regional Development and Construction and water agency Apele Moldovei should support regionalisation in practical ways. This can start with defining and clearly documenting the steps and procedures under which, in the context of WSS services, assets can be transferred from one entity to another on a solid legal and contractual basis.

Paving the way for sustainable business models

The fully regionalised WSS sector structure will be achieved over 10-20 years. Meanwhile, the sector needs business models that are sustainable, at least for the transition period. Also, there might be several different sustainable business models for regionalised WSS services (OECD, 2016[3]). The sustainability criteria apply equally to the financial and economic, as well as to the quality of service and environmental aspects.

The traditional municipality-owned utility model is not always sustainable let alone optimal. Increasingly, Moldova needs to obtain surface water from the rivers Prut and Dniester. These sources are important either to save remaining groundwater reserves or because the quality of these resources is no longer acceptable. This alone is an urgent reason to work out other business models, including co‑operation with other municipalities and operators.

Rural areas especially need to look for these alternatives. They may be permanent or transitional, such as during the regionalisation process. They may be based on public or private sector management, or on co-operative or not-for-profit association. The business model shall follow the needs, preferences and local capacity constraints in respective communities.

Several business models are described with a focus on the options for rural sanitation in Moldova (see Table 4.1). These models differ from one another on service structure, degrees and forms of regionalisation (consolidation) and delegation, use of technology and service level. There are different needs determined mostly on the location of the service area. Suburban localities have different options than rural agglomerations or remote localities (OECD EAP Task Force, 2013[4]).

Table 4.1. Medium-term sanitation service options for various localities

|

Type of area |

Degree of regionalisation |

Service provision |

Professional services |

Technology |

Sector financing |

Incentives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Suburban |

Regionalised |

Joint stock company based on existing Apacanal multi-purpose utilities |

Small need for “light regionalisation” |

Piped sewage collection+ WWTP |

Improved social programme |

Fiscal incentives for capital investments; |

|

Agglomeration |

performance- based contracts |

|||||

|

Remote localities |

Regionalised |

Association of localities or assets holding company hiring an operator |

High need for “light regionalisation” |

Piped sewage collection + WWTP |

Improved social programme+ solidarity fund |

Fiscal incentives for capital investments; |

Source: (OECD EAP Task Force, 2013[4]), Business Models for Rural Sanitation in Moldova..

The challenge of developing sustainable business models relates closely to the challenge of regionalisation. It would be a mistake, however, to believe that because of regionalisation there is no need to think about sustainable business models. First, a regionalised structure implies another business model and a new corporate orientation. Second, the initial phase of regionalisation may already take a decade. During that time and thereafter, there is a need for viable business models, including ones adopting more flexible standards of service, particularly for remote rural areas.

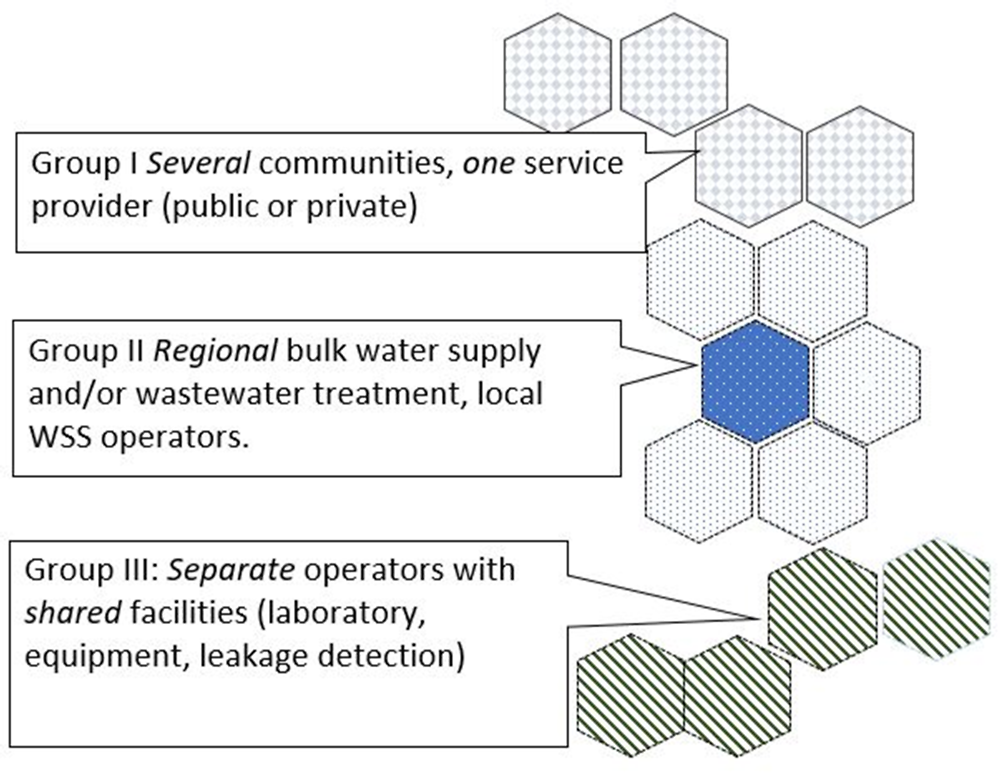

Business models for different forms and degrees of regionalisation are presented in Figure 4.5. It is expected that over the longer term the sector will move from Model 1 to Model 3. However, even once Model 3 has been completely implemented there can be reasons to structure businesses differently across the regions and even within regions. Regionalisation does not mean centralised standardisation. Both in water and sanitation it may be efficient to make use of outsourcing, private sector involvement, Water Users’ Associations or co‑operatives of rural drinking water users, different technologies, etc. The optimal degree and form may be different from region to region and different within a region.

Figure 4.5. Business models for different forms and degrees of regionalisation

Recommendation 13: Facilitate emergence of sustainable business models that serve communities’ needs.

Different options are presented in Figure 4.6. (OECD EAP Task Force, 2013[4]) OECD EAP Task Force (2013) furthermore recommends preparing guidelines for local governments on establishing (inter-municipal) joint stock companies (e.g. for septic tank operators, regionalised operations of utilities). It also recommended that such guidelines include templates for statues, regulations and performance-based service contracts.

Figure 4.6. Sustainable regional service provision structures

Source: Author's own elaboration

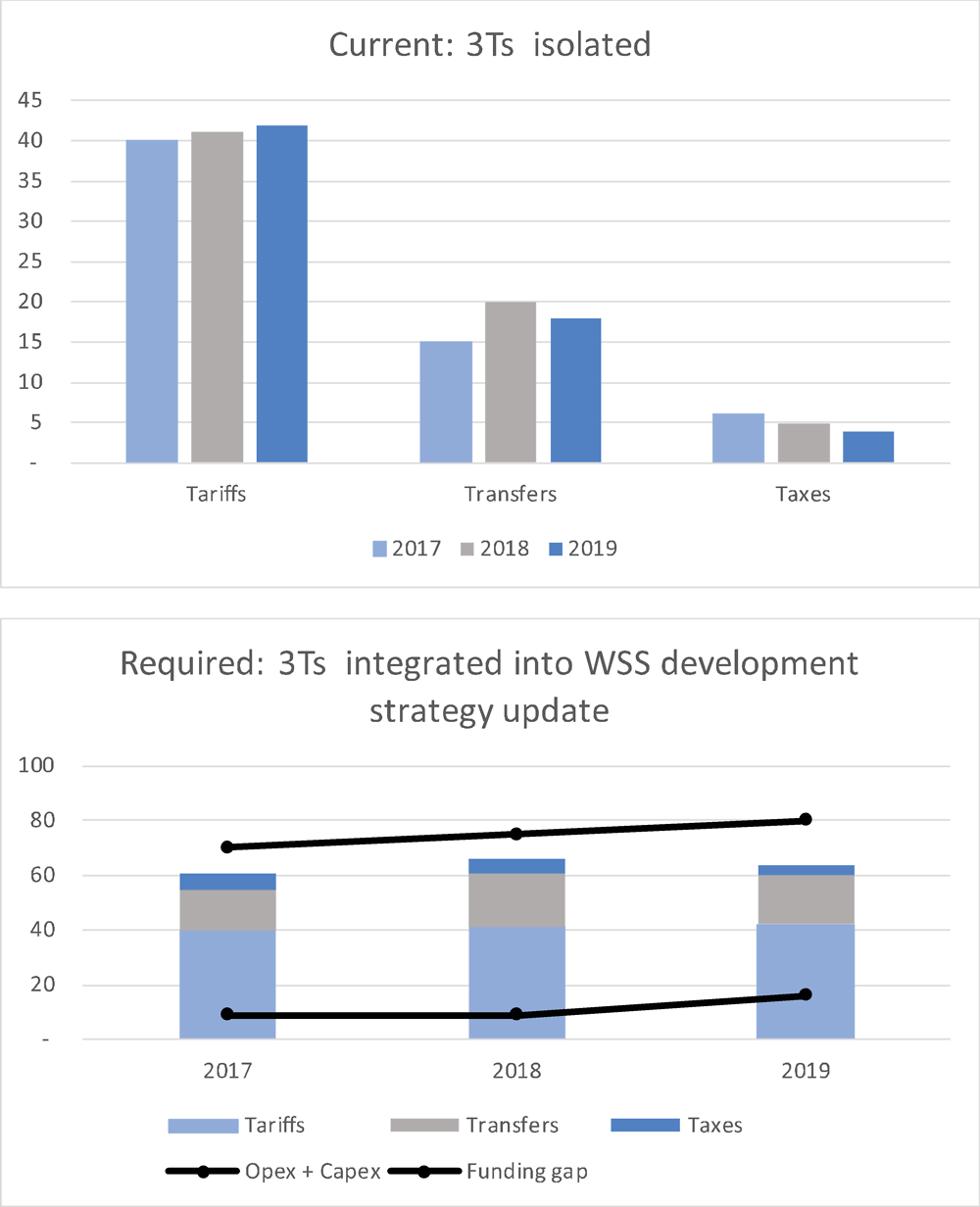

Realising the optimal mix of the 3Ts

As described in section 2.4, the ultimate sources of funding for a WSS operator consist of a mixture of the 3Ts: “tariffs, taxes and transfers”. In Moldova, the utility sector cannot develop on tariffs alone. It must rely on a reliable stream of budgetary resources (mobilised through taxes) and international grants (transfers). To make these streams reliable, planning and co‑ordination are necessary.

RecommendationRecommendation 14: Develop a data collection, recording and projection system through the Ministry of Environment and water agency Apele Moldovei.

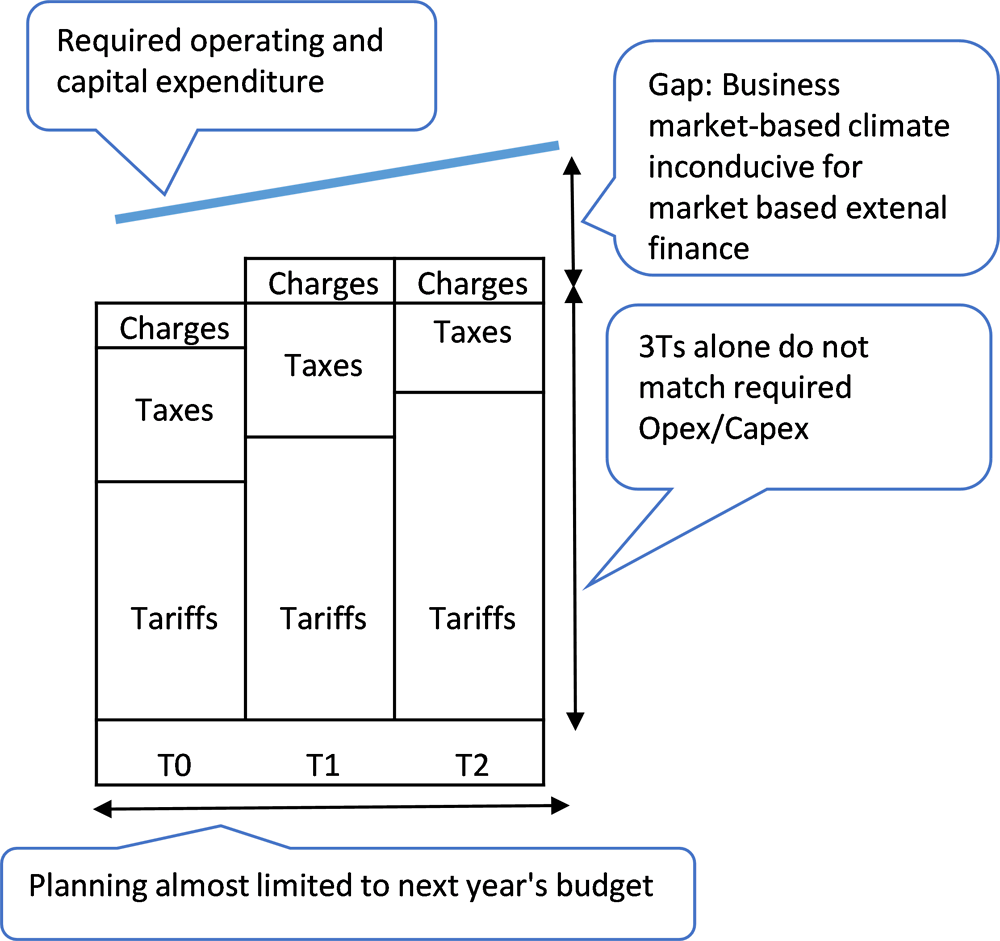

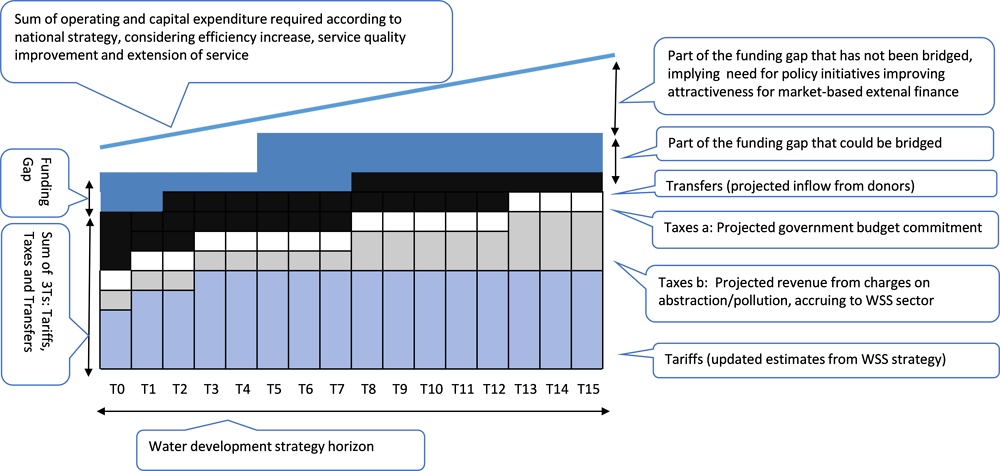

By developing a data collection, recording and projection system, the 3Ts can be considered in an integrated way, as illustrated in Figure 4.7, for past, present and future. These data are to be updated and published annually.

Figure 4.7. Integrating accounting for the 3Ts

Note:Data for illustration of the concept only.

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Recommendation 15: Update projection of the 3Ts for a rolling 15-year period (MoT).

In addition to updating projection of the 3Ts for a rolling 15-year period, MoT should also estimate the required operating and capital expenditures. To that end, it should use both bottom-up estimates and experience from transition countries with EU acquis compliance costs. In this way, the funding gap estimate can be updated annually and necessary changes in policy, regulation and financing capacity signalled and initiated. This is vital for external finance, discussed in section 4.8. Costs and funding will not match automatically and policy makers face difficult choices. Only informed choices allow for an optimised mix of 3Ts, based on ruling out other, less attractive options and mixes.

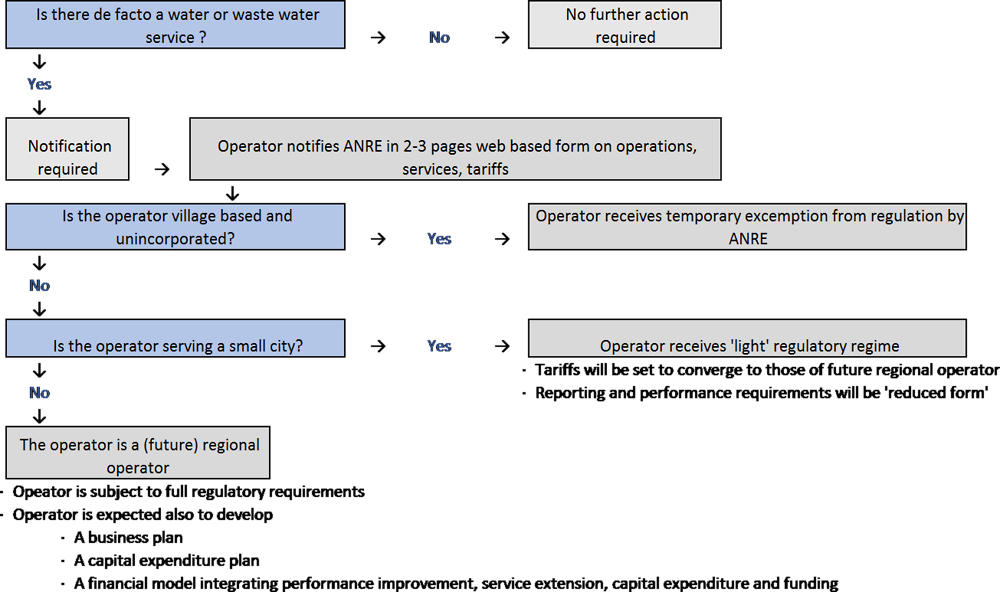

Box 4.1. Differentiated and “light” regulation

The economic regulator ANRE can play a role in most areas of the ERS – from performance incentives to regionalisation and from sustainable business models to affordability. In Moldova, there is a wide variety of WSS providers, from large corporatised enterprises in the cities to small-scale (private) operators. Often, local authorities provide water supply directly themselves.

Only operators registered with ANRE are within its scope. In practice, these are the approximately 40 urban WSS operators. Among that group, differences are large, too. Some have already achieved economies of scale, such as Apacanal Chișinău and the operators in larger cities. For this category, i.e. the future regional operators, economic regulation can be developed in accordance with recommendations from sections 4.4 – 4.5.

Others may well merge into bigger entities in the future; for this category, a different approach is to be developed. It would suffice to ensure these are “moving in the right direction” i.e. making progress on regionalisation. Rather than complying with a complex tariff methodology, those utilities should converge their tariffs with those of the future regional operator.

Most small operators “fly under the radar” by not registering as a utility. In this way, ANRE cannot assess the supply conditions, demand and needs of a sizeable proportion of the population (58%). In a broader context, that implies the national government of Moldova overlooks supply to these areas (which means it is often substandard). Therefore, it would be good to register any water supply or sanitation service, if only for planning and monitoring purposes. The government may immediately exempt small operators from licensing and compliance with tariff regulations for five years. As outlined above, smaller operators already registered require a light regulation. Light regulation also involves a reduced number of service quality indicators to monitor a much more pragmatic tariff-setting process. In this way, ANRE can facilitate national policy, of which regionalisation is a cornerstone; focus on future regional operators; and still keep an eye on future water supply investment needs and required consolidation of WSS services in the country.

Source: Author’s own elaboration; (Tuck et al., 2013[2]), “Water Sector Regionalization Review: Republic of Moldova.”

Extending the use of economic instruments

Tariffs, discussed already in Recommendation 6, can be seen as the most important of all economic instruments. Apart from tariffs, however, many other instruments influence behaviour and can help achieve policy objectives. In broad categories, these are charges, such as abstraction and pollution charges; subsidies on products or processes; market-based instruments, such as tradable permits; and voluntary agreements, such as between upstream and downstream water users. Economic instruments are recommended as a tool for environmental policy, next to traditional “command and control” measures.

In Moldova, much of the potential of economic instruments is yet to be realised. This might be surprising considering the emerging water scarcity and pollution issues. Still, economic instruments must be designed with a good understanding of the following, among others:

the possible environmental and social impact

the country’s institutional, management and expert capacity to implement.

Therefore, it is logical to first improve use of existing economic instruments. Apart from tariffs, these include charges on water abstraction and pollution. (OECD EAP Task Force, 2007[5]) already made a large number of recommendations to make the system simpler and more effective. (UNECE, 2014[6]) reports these have not been subject to further development since 2005, and adds more recommendations.

These recommendations, no matter how urgent, are made in a broader environmental context. In relation to the WSS sector and the required investments for compliance with the water-related EU acquis (only) the following two recommendations are made for specific instruments (OECD EAP Task Force, 2007[5]; UNECE, 2014[6]).

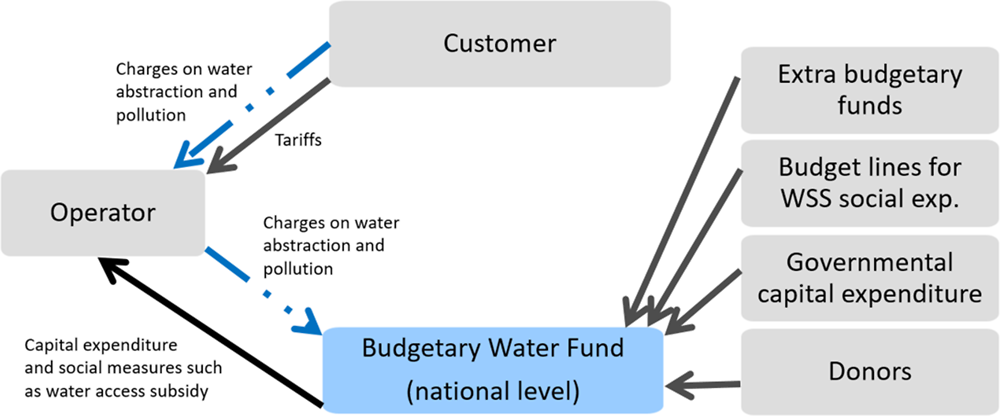

Instrument 1: Development of a budgetary water fund within the National Ecological Fund

Recommendation 16: Create a budgetary water fund within the NEF.

As outlined in section 4.6, there is a need to monitor investment flows into the sector, in addition to increasing these flows up to the absorptive capacity of the country. A fund for water outside of the NEF will create an additional administrative burden and may face obstacles from international financial institutions. Within the NEF, however, it is possible to administer and ring-fence the flows into the WSS sector. The proposed budgetary water fund within the NEF maintains required budgetary flexibility. Investment may be higher or lower in a year depending on macroeconomic circumstances and evolving government priorities (which can change drastically after the next elections). However, it is important to secure stable funding for capital investments in WSS, as water policy objectives cannot be achieved within one election cycle. The long-term progress on this investment programme must be recorded, monitored and kept on the policy agenda. This can be achieved within the structure of the NEF. The Budgetary Water Fund is illustrated in Figure 4.8.

Charges for water abstraction and water pollution can become major sources of funding to the Budgetary Water Fund. However, other sources of funding should not be excluded e.g. the excise tax levied on products contributing a lot to diffuse water pollution: toxic agri-chemicals, motor oil, synthetic detergents with high content of phosphorus (P) and (or) nitrogen (N), etc.

Recommendation 17: Increase water abstraction and water pollution charges and to broaden the base.

All water abstracted for domestic consumption by household (as well as by some other not-for-profit entities) is exempted from the abstraction charge. This exemption serves no purpose if tariffs are to be harmonised anyway.

Recommendations of the system can be simplified. Charges for surface water and groundwater abstraction must eventually be raised to provide incentives for more economic and effective use of water and to raise funds for capital expenditure. Existing policy to preserve groundwater can be supplemented by a relatively higher water abstraction charge on fresh groundwater of drinking quality (OECD EAP Task Force, 2007[5]; UNECE, 2014[6]).

The proceeds of the water abstraction and water pollution charges shall return transparently back to the sector in the form of capital expenditure subsidies. They might also be used for social support measures such as reducing the costs of receiving access to water.

Detailed recommendations for further general reform of the NEF have been made already through two UNDP projects in 2012‑15 and are not repeated here. Improvements have been made by bringing NEF back into the consolidated budget. However, follow-up on these recommendations will bring the NEF (and the NFRD) further in compliance with standards of good public financial management.

Figure 4.8. Workings of the Budgetary Water Fund

Source: Author's own elaboration

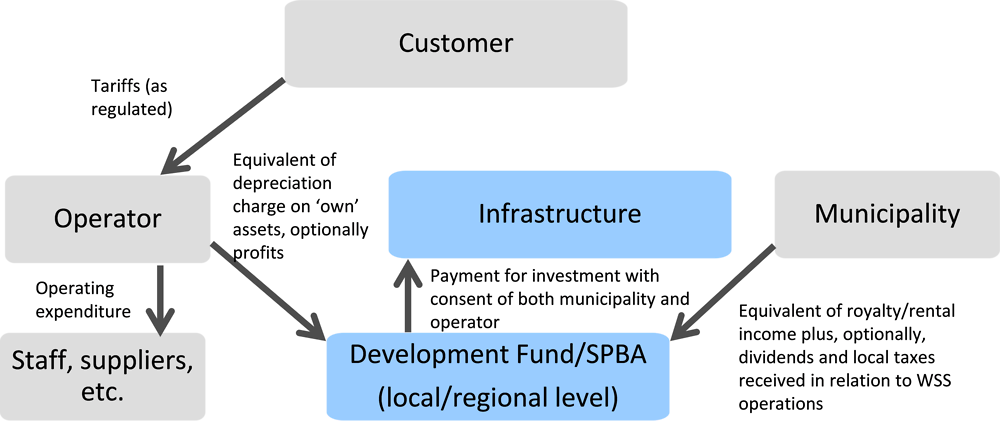

Instrument 2: Creation of Development Fund

Recommendation 18: Ring-fence the (share of) revenue from tariffs that cover the depreciation expense, as well as profit, municipal taxes, royalties and lease fees (if any).

This type of revenue is to be used exclusively for capital investment and debt repayment. Romania’s Maintenance, Replacement and Development funds represent the most advanced way to do this (Popa T., 2014[7]). However, an escrow account, or a special purpose restricted bank account (SPBA) could achieve this objective as well.

The use of the word “fund”, therefore, does not imply that a legal entity must be established to manage the money as is the case in Romania. The underlying economic substance of the fund concept can be achieved with an escrow account. In theory, it could be achieved within the utility accounting system, but this is not recommended.

Ring-fencing the counter-value of the depreciation expense is necessary. It would otherwise easily move into sustaining inefficiencies at the operator level or sustaining tariffs below cost recovery.

There is a further reason why the Development Fund and the associated ring-fencing can be important for the sector. It would rule out any future cash benefits from owning municipal infrastructure. In this way, it overcomes a possible obstacle to regionalisation.

Any municipal revenues in the form of WSS-related royalties, lease or concession fees, profit or otherwise would flow back to the fund for re-investment. In this way, any unresolved ownership question becomes less of an obstacle in the regionalisation process. Ownership would no longer represent any revenue stream for any municipality (see Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9. Workings of the Development Fund

Source: Author's own elaboration.

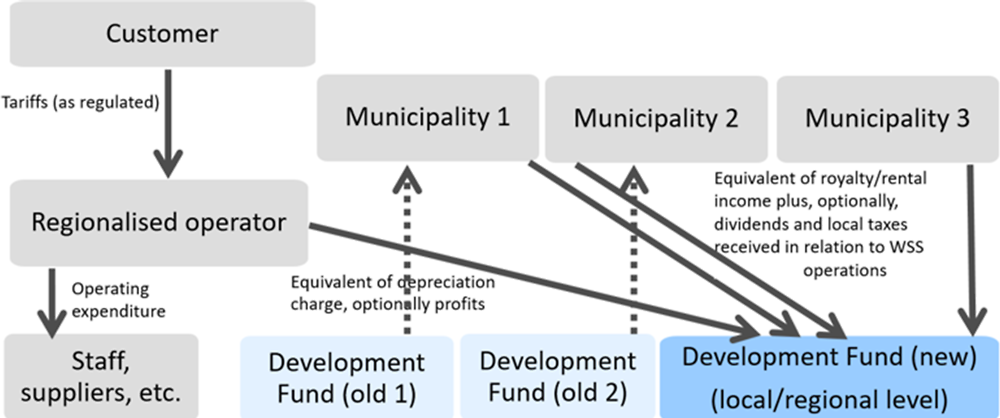

The Development Fund is a local or regional fund. It is not a substitute for a national instrument and can co-exist with it. Figure 4.10 illustrates how the instrument can operate in parallel with the regionalisation process in Moldova. Each time a service area is extended or merged, a new development fund is created. If this is done through an SPBA the effort and costs are marginal. One needs to open the account, arrange for the purposes for which it can be used and for authorisation (joint signatory rights).

The existing (old) SPBAs will be gradually depleted, with investment going to the service areas foreseen in each old SPBA.

Once depleted, the old SPBA is closed. Typically, that shall be within a year after the merger (or expansion). However, as of the date that merger or expansion becomes effective, all contributions from all constituent municipalities and from the regionalised operator will go into the new SPBA. The challenge for a merged entity will be to distribute the investments over the service area in a manner that is acceptable, fair and economically efficient. The leading principle here shall be economic rationale. For any given service level, rural WSS will typically require more investment per capita. Per km network contributions to the Development Fund from urban areas will be larger than from rural areas. In case of a rationalised WSS service, this is the main channel of solidarity from urban to rural areas.

Figure 4.10. Development Fund in the context of regionalisation

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Improving access to external finance to bridge the funding gap in WSS

Section 2.4 mentioned the need for assessing the funding gap i.e. the difference between the projected sum of the 3Ts and the sum of the projected operating and capital expenditure at national and local level. To bridge this funding gap, one must find market-based external finance as was illustrated in Figure 1.4.

External finance to bridge the funding gap

Recommendation 19: Develop policy to increase the attractiveness of Moldova’s WSS operators for external financiers.

Policy makers and operators shall consider the effect of their actions on external financiers and their perception of the Moldovan market for WSS debt. Most of the recommendations outlined in this report will already improve attractiveness. Regionalisation, transparency and availability of data, business plans and improved economic regulation are a few examples. There is, however, more the government can do in this respect. (Verbeeck, 2013[8]) lists the lack of instruments (such as credit lines) and lack of credit ratings as important obstacles in many transition countries. (OECD, 2010[9]) provides further detail and comprehensive analysis that is of relevance to Moldova, too. Importantly, attracting external finance requires different types of projections than in use in Moldova (see Figure 4.11 and Figure 4.12).

Figure 4.11. External finance: Current type of projection

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Figure 4.12. External finanance: Required type of projection

Source : Author's own elaboration.

Establishing strong and well-targeted social measures as a key element of the ERS

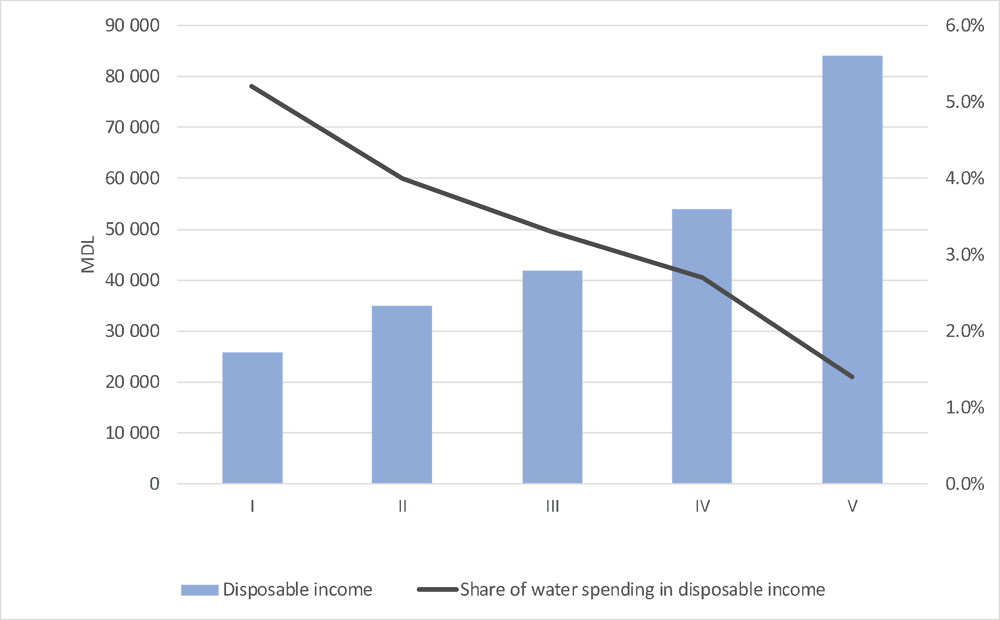

The percentage of household income spent on WSS services (see Figure 4.13) is bigger in Moldova than in any other country in Europe. For over a decade, the OECD and others have warned that necessary tariff increases need to be accompanied by targeted social measures and that an appropriate mix of targeted social measures in WSS is much more cost-effective than low tariffs for everyone. It also stresses that access to WSS services is of even bigger importance than the share of income spent on WSS. Recommendations are made for establishing a sustainable domestic financial support mechanism (DFSM) that relates specifically to WSS (OECD, 2017[10]). During a forthcoming transitional phase of rapid tariff increases, DFSM will be particularly necessary.

Figure 4.13. Disposable household income (lei per annum) and the share of income spent on WSS services, by income quintiles (2013 data)

Note: The figure was prepared for the economic analysis for the Nistru River Basin Management Plan.

Source: Author’s own elaborations based on the National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova (NBS) data available at www.statistica.md/index.php?l=en.

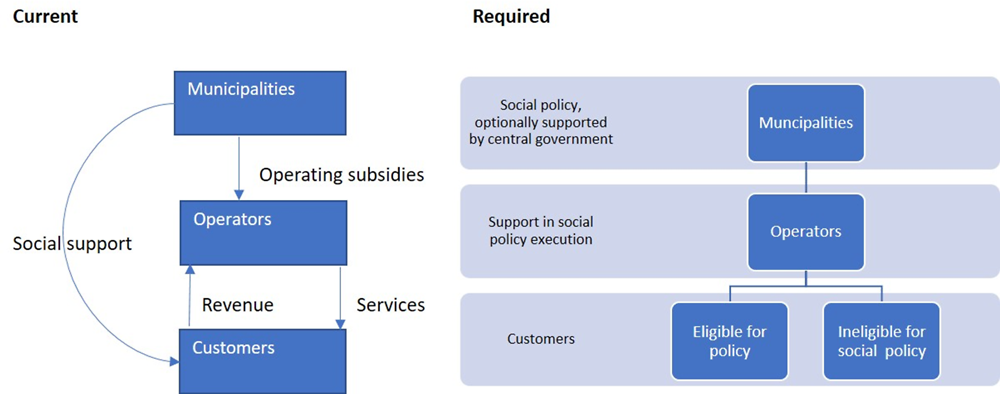

The present and required situations are illustrated in Figure 4.14. Municipalities and central government have certain means to provide citizens with income support. It is not specifically for WSS expenses. A large amount is “spent” on cross-subsidising households and on keeping tariffs low in general. Redirecting these resources for targeted social measures in WSS can make a sizeable difference in access to, and affordability of, WSS services for the poor.

Figure 4.14. Present and required situation with respect to WSS-related social measures

Source: Author's own elaboration

There is still no WSS-related targeted social measure in place. Therefore, this report makes a single, but specific and important recommendation, for a single targeted social measure.

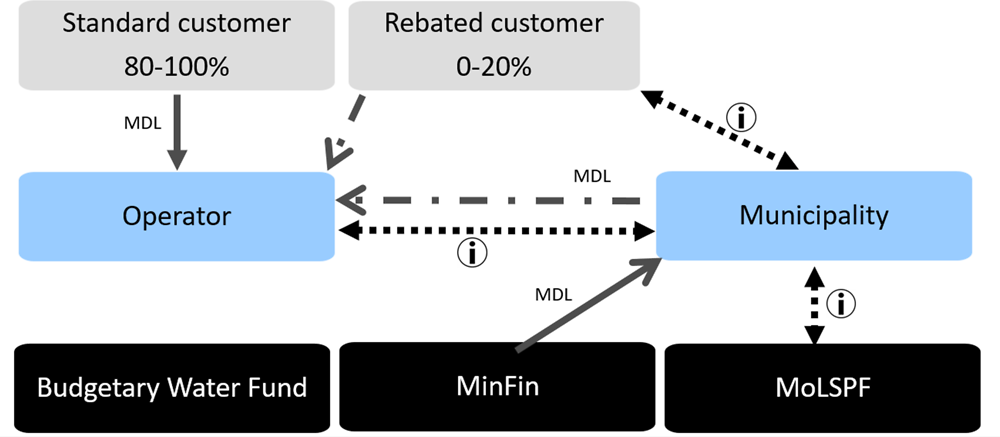

Recommendation 20: Implement a WSS-related social measure in the form of a rebate system.

A rebate is a discount on the bill in the form of a fixed monetary amount. The size of the rebate may depend on one’s status as a social case. It may vary with the number of persons living in the household and possibly with household income. The latter would eliminate a poverty trap, but induces more administrative costs.

The rebate shall be based on guidelines issued by ANRE or MoLSPF, but shall leave considerable room for local customisation in terms of size and eligibility. One possible option is presented in Figure 4.15.

In any case, the effect shall be neutral on revenues of the operator. That means the operator receives back what is provided as discounts – through higher tariffs and/or subsidies. The financial support of municipality, MoLSPF, MoF and/or from the proposed budgetary water fund is, of course, welcome. However, a rebate mechanism could also function in the absence of any external support. The active involvement of municipalities in determining the poverty line and eligibility criteria for support is a requirement. There is also a need for data exchange between operator and municipality, regular inspection and annual revision of the instrument. Annex C provides a more detailed description of the rebate mechanism.

A rebate mechanism supports the demand for WSS services. This could be an important measure in the short term during a period of tariff increases. Physical access to WSS services is at least equally important over the longer term. This could, for instance, be a micro finance mechanism to support the costs of connection.

Figure 4.15. Workings of a rebate mechanism

Source: Author's own elaboration.

Listed recommendations, key resource documents and TA requirements

The 20 recommendations from the preceding sections aim at improving the ERS for WSS in Moldova and/or creating a more conducive environment for its successful performance. The distinction between these categories is in some cases more obvious than in others. In the case of regionalisation, the causality is both ways: regionalisation would facilitate improved performance of the ERS, while a sound ERS would facilitate regionalisation. Without going into extensive detail, Table 4.2 indicates the type of relationship for each objective.

Table 4.2. Demands on ERS, objectives and the role of a sound ERS, and situation as of today

|

Objectives |

Demands on ERS |

A sound ERS… |

However, as of today… |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. A tariff that gives incentives to perform better |

Monitor and steer performance improvement (1) |

… must set tariffs that provide smart incentives to perform better |

Shortcomings in methodology and execution (section 3.3). |

|

2. More decisive regionalisation of services |

Focus on regionalised entities (2) |

… will facilitate AND, if regionalisation is done, ERS itself would perform better |

Legal/institutional complexity, insufficient managerial capacity and lack of incentive. Daunting regulatory task for ANRE. |

|

3. The nurturing of sustainable business models |

Facilitate the emergence of sustainable business models (3) |

… facilitates the introduction of sustainable business models |

Significant legal, regulatory and institutional barriers to business models other than the single municipality-owned utility. |

|

4. An optimal mix of the “3Ts” of tariffs, taxes and transfers, based on an up-to-date sector strategy |

Tariff increases to fund WWTPs (4) |

… leads to an optimal mix |

Lack of integrated co‑ordination and planning on 3Ts. |

|

5. Proper use of economic instruments to achieve set WSS policy objectives |

Recognise need for external finance (7); economic instruments to finance particularly WWT and rural WSS |

… provides the key EI in the form of tariff and facilitates the use of other instruments |

Limited use of abstraction charge as economic instrument. |

|

6. The use of external finance to bridge the projected funding gap |

Allow for achieving SDGs on WSS (8) |

… facilitates access to external finance by reducing regulatory risk |

Absence of even nominal change in tariffs for many years. No policy to lure financial sector to WSS investments. |

|

7. Well-targeted WSS-related social protection measures |

Protection of poor (5) & affordability of service (6) |

…provides guidance leading to effective and targeted social protection measures |

Absence of WSS- related social measure, although significant tariff increases may be imminent. |

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

For easier reference, all recommendations are summarised.

Recommendation 1: Re-establish the WSS Commission as a body providing high-level policy co‑ordination in WSS.

The subsequent recommendations are grouped per subject, followed by an indicative road map, key resource document(s) and an indication on any required Technical Assistance to implement them.

Providing incentives towards performance improvement

Recommendation 2: Perceive the role of economic regulator as a facilitator of performance improvement and a broker between operator and customer.

Recommendation 3: Require and analyse quality business plans from operators.

Recommendation 4: Provide a template for business plan, setting the minimum criteria and an Excel-based template financial model in compliance with modelling standards.

Recommendation 5: Provide incentives towards resolving irregularities at apartment blocks. The costs of internal leakages (technical and commercial water losses) shall be, and remain firmly with, the owners of the apartments.

Recommendation 6: Confine Law 303 on WSS services to tariff-setting principles and to develop a new tariff methodology based on these principles.

Recommendation 7: Develop a dynamic, rather than static tariff-setting principles.

Recommendation 8: Provide the independent economic regulator already with more discretion, while continuing to use the existing tariff methodology as a guiding document.

Recommendation 9: Publish an annual performance report comparing performance and progress of the urban water operators (economic regulator).

Technical Assistance (TA) required?: YES

Objective: To facilitate development of an economic regulator as foreseen in this report, EU Association Agreement countries typically receive two-three years of TA. This is provided by a small team of one international expert supplemented by a number of short-term experts. Policy consensus on the role of regulator is a prerequisite.

Facilitating the regionalisation of services

Recommendation 10: Proceed with regionalisation decisively, including making future government funding conditional to prior regionalisation steps.

Recommendation 11: Adopt the approach, road map and timeline (Tuck et al., 2013).

Recommendation 12: Ensure the Ministry of Regional Development and Construction and water agency Apele Moldovei provide practical support towards regionalisation in relation to process, transfer of assets and guidelines.

Technical Assistance required?: YES. Experience from regionalisation projects in Romania indicates the need for one-two years of TA per region. Before that, support to policy development is needed over one-two years.

Paving the way for sustainable business models

Recommendation 13: Facilitate the emergence of sustainable business models that serve communities’ needs through, among others, guidelines, template regulations and support on inter-municipal co‑operation.

Technical Assistance required?: NO

This subject has many interlinkages with other ones for which TA is recommended i.e. regulation and regionalisation.

Realising the optimal mix of 3Ts

Recommendation 14: Develop financial data collection and recording system so that the 3Ts can be considered together (Ministry of Environment and water agency Apele Moldovei).

Recommendation 15: Update projection of the 3Ts, operating and capital expenditures to a rolling 15-year period. The resulting updated funding gap estimate signals a need for change in policy, regulation or financing capacity.

Technical Assistance required?: YES, being executed.

This subject has many interlinkages with other ones for which TA is recommended i.e. regulation and regionalisation.

Extending the use of economic instruments

Recommendation 16: Create within the NEF a budgetary water fund (BWF).

Recommendation 17: Expand water abstraction and water pollution charges and base to be compatible with an optimal mix of 3Ts. Proceeds of these charges are to be used for investment in the sector and for WSS-related social measures.

Recommendation 18: Create a development fund at operator level applying the valuable experience Romania has obtained with this instrument.

Technical Assistance required?: YES

The creation of the BWF requires reform of the NEF. Earlier consultancies on this subject have had some effect, but not all recommendations have been implemented. A BWF should be created within a broader reform of the NEF (ideally, co-ordinated with a reform of the NFRD).

2. The creation of the instrument of the Development Fund may be integrated together with the TA for regionalisation. But the creation of this fund does not depend on regionalisation and should not wait for it. A small TA (up to three-month assignment of a project manager plus a lawyer) could pave the way for the fund roll-out.

Improving access to external finance to bridge the funding gap in WSS

Recommendation 19: Develop policy to increase the attractiveness of Moldova’s WSS operators for external financiers. Furthermore, policy makers and operators shall consider the effect of their actions on external financiers and their perception of the Moldovan market for WSS debt.

Technical Assistance required? YES. International financial institutions may be interested to provide this type of TA.

Establishing strong and well-targeted social measures as a key element of the ERS

Recommendation 20: Implement a WSS-related social measure in the form of a rebate system. The rebate shall be neutral on revenues of the operator and leave considerable room for local customisation in terms of size and eligibility.

Technical Assistance required?: YES

It is recommended to seek TA for the elaboration of options for and implementation of a particular measure, such as the rebate measure. It is not recommended to seek further TA for the preceding analysis and decision making.

Implementation

The 20 recommendations resorting under the seven objectives have interlinkages and somewhat overlap. Increasing the role of ERS in providing stronger incentives towards performance improvement is perhaps most vital for further development of the ERS. Yet the type of economic regulation depends on the number of regulated entities. It therefore depends on sector structure and degree of regionalisation (consolidation) and delegation. Progress on economic regulation depends ultimately on progress with regionalisation.

Regionalisation shall be complemented by adoption of a sustainable business model for WSS services. During the regionalisation process, additional forms of inter-municipal co‑operation have to be worked out.

These business models are all funded through a mix of tariffs, taxes and transfers (3Ts) to cover the projected operating and capital costs (opex & capex). No business model is complete in the absence of an integrated projection of the 3Ts.

Economic instruments are part of the ERS. The use of economic instruments therefore cannot be considered in isolation either. They provide for incentives and are a revenue source to co-finance much-needed investment.

The gap between the sum of the 3Ts and opex & capex can be bridged with external funding, typically market-based. For external finance to flow, however, credibility and creditworthiness must be enhanced. Together, operators, municipalities and central government should be able to better familiarise financiers with the WSS sector in Moldova and to convince them about investment opportunities.

Existing and new measures will lead to an increase in tariffs and charges in the WSS sector in which affordability of service is already under pressure in Moldova. Such increases will not be feasible without a credible social measure that relates specifically to the water sector.

Progress on one objective facilitates that on others. The recommendations relate to one another. A pick and choose approach is therefore difficult. But there are yet many details that must be filled in during later stages. This leaves room for customisation according to circumstances and future developments. Certainly, to clarify, agree, adopt, consult with stakeholders and implement requires a formidable effort from WSS policy makers, civil servants, municipalities and operators.

Any implementation plan drawn up in this stage will therefore be under the risk of not being fully implemented in the future. But showing a conceivable implementation framework helps bring implementation closer.

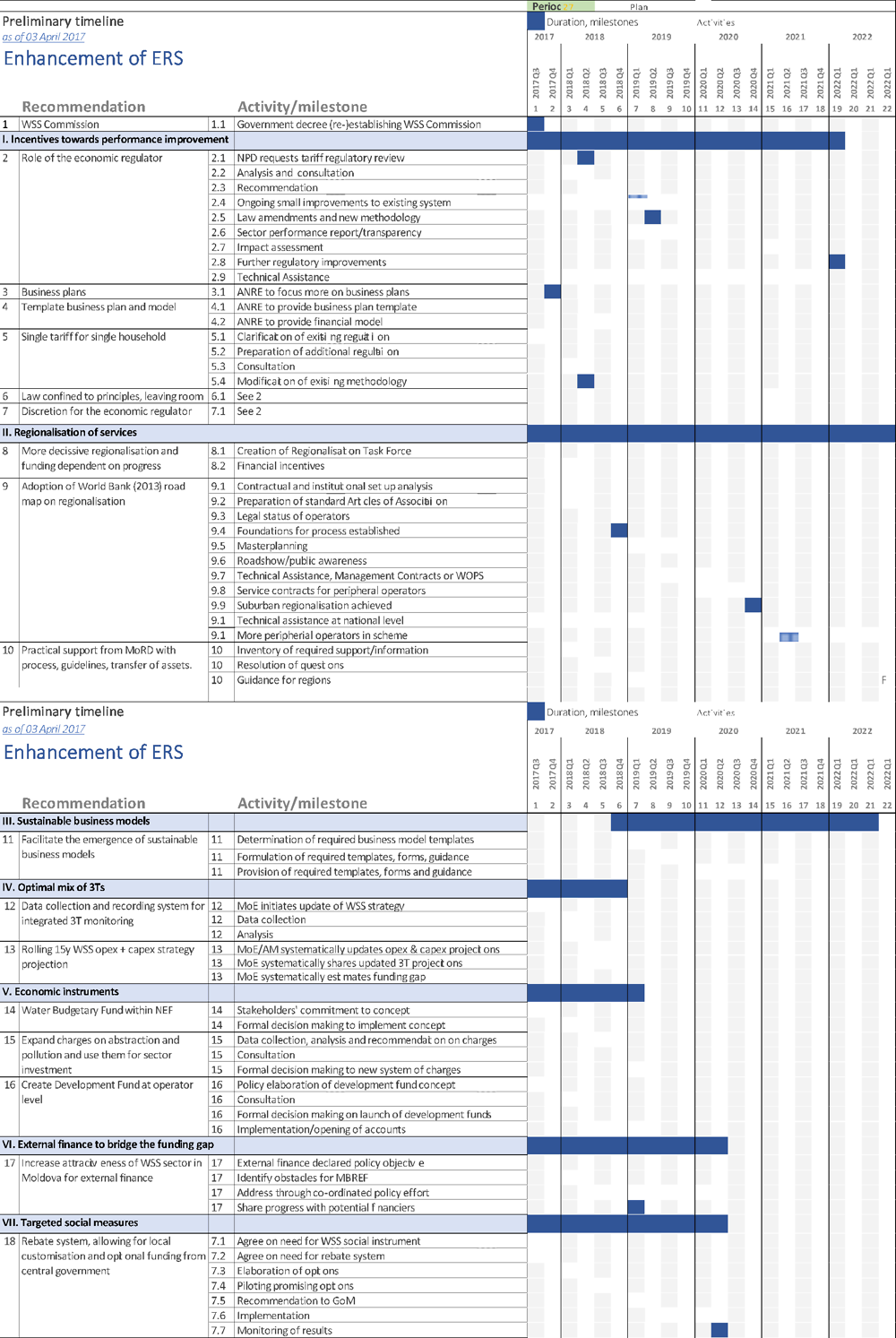

Figure 4.16 on the next pages therefore provides an indicative implementation plan. It has been drawn up in the understanding that many activities, responsibilities, outputs and milestones will require further elaboration and blueprinting during the process. Policy makers and stakeholders shall make a start and work out along the way: (i) the more exact needs for Technical Assistance; (ii) a more elaborated plan for implementation of specific activities in WSS (e.g. a mid-term action and investment plan); and (iii) the need for, and the content of, required legal or regulatory amendments.

The NPD can support this by:

1. subscribing to the recommendations elaborated in this report

2. encouraging policy makers to initiate implementation

3. monitoring and disseminating actual achievements systematically.

Figure 4.16. Indicative implementation framework

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the analysis presented in this report.

References

[1] ANSRC (2014), Presentation of National Regulatory Authority for Municipal Services of Romania, http://www.danube-water-program.org/media/dwc_presentations/day_0/Regulators_meeting/2._Cador_Romania_Viena_ANRSC.pdf.

[13] Berg, S. et al. (2013), “Best practices in regulating State-owned and municipal water utilities”, http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/4079/S2013252_en.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 February 2018).

[17] CASTALIA (2005), Defining Economic Regulation for the Water Sector, https://ppiaf.org/sites/ppiaf.org/files/documents/toolkits/Cross-Border-Infrastructure-Toolkit/Cross-Border%20Compilation%20ver%2029%20Jan%2007/Resources/Castalia%20-%20Defining%20Economic%20%20Regulation%20Water%20Sector.pdf.

[16] Demsetz, H. (1968), “Why Regulate Utilities?”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 11, pp. 55-65.

[26] EAP Task Force (2013), Business Models for Rural Sanitation in Moldova, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/Business%20models%20for%20rural%20sanitation%20in%20Moldova_ENG%20web.pdf.

[23] Eptisa (2012), Republic of Moldova’s Water Supply and Sanitation Strategy (Revised Version 2012), http://www.serviciilocale.md/public/files/2nd_Draft_WSS_Strategy_October_final_Eng.pdf.

[11] Geert Engelsman, M. (2016), Review of success stories in urban water utility reform, https://www.seco-cooperation.admin.ch/dam/secocoop/de/dokumente/themen/institutionen-dienstleistungen/Review%20of%20Successful%20Urban%20Water%20Utility%20Reforms%20Final%20Version.pdf.download.pdf/Review%20of%20Successful%20Urban%20Water%20Utility%20Reforms%20Final%20Version.pdf.

[28] Massarutto, A. (2013), Italian water pricing reform between technical rules and political will, http://www.feem-project.net/epiwater/docs/epi-water_policy-paper_no05.pdf.

[21] Ministry of Environment of Republic of Moldova (n.d.), Reports on Performance in 2010-2015, http://mediu.gov.md/index.php/en/component/content/article?id=72:fondul-ecologic-national&catid=79:institutii-subordonate.

[10] OECD (2017), Improving Domestic Financial Support Mechanisms in Moldova’s Water and Sanitation Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252202-en.

[24] OECD (2017), Improving Domestic Financial Support Mechanisms in Moldova’s Water and Sanitation Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252202-en.

[3] OECD (2016), OECD Council Recommendation on Water, https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Council-Recommendation-on-water.pdf.

[25] OECD (2016), Sustainable Business Models for Water Supply and Sanitation in Small Towns and Rural Settlements in Kazakhstan, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264249400-en.

[27] OECD (2015), “Regulatory Impact Analysis”, in Government at a Glance 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2015-39-en.

[31] OECD (2015), The Governance of Water Regulators, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en (accessed on 7 February 2018).

[12] OECD (2014), The governance of regulators..

[9] OECD (2010), Innovative Financing Mechanisms for the Water Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264083660-en.

[29] OECD (2010), Innovative Financing Mechanisms for the Water Sector, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264083660-en.

[4] OECD EAP Task Force (2013), Adapting Water Supply and Sanitation to Climate Change in Moldova, https://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/Feasible%20adaptation%20strategy%20for%20WSS%20in%20Moldova_ENG%20web.pdf.

[5] OECD EAP Task Force (2007), Proposed system of surface water quality standards for Moldova: Technical Report, http://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/38120922.pdf.

[22] OECD EAP Task Force (2003), Key Issues and Recommendations for Consumer Protection: Affordability, Social Protection, and Public Participation in Urban Water Sector Reform in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia, http://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/14636760.pdf.

[18] OECD EAP Task Force (2000), Guiding Principles for Reform of the Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Sector in the NIS.

[20] Pienaru, A. (2014), Modernization of local public services in the Republic of Moldova, http://www.serviciilocale.md/public/files/prs/2014_09_18_WSS_RSP_DRN_FINAL_EN.pdf.

[7] Popa T. (2014), “A smart mechanism for financing water services and instrastructure” IWA, https://www.iwapublishing.com/sites/default/files/documents/online-pdfs/WUMI%209%20%281%29%20-%20Mar14.pdf.

[34] Programme, U. (ed.) (2015), Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development, Communications Development Incorporated, Washington DC, http://dx.doi.org/978-92-1-057615-4.

[30] Rouse, M. (2007), Institutional Governance and Regulation of Water Services | IWA Publishing, IWA, London, https://www.iwapublishing.com/books/9781843391340/institutional-governance-and-regulation-water-services.

[14] Smets, H. (2012), “CHARGING THE POOR FOR DRINKING WATER The experience of continental European countries concerning the supply of drinking water to poor users”, http://www.publicpolicy.ie/wp-content/uploads/Water-for-Poor-People-Lessons-from-France-Belgium.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2018).

[15] Trémolet, S. and C. Hunt (2006), “Water Supply and Sanitation Working Notes TAKING ACCOUNT OF THE POOR IN WATER SECTOR REGULATION”, http://regulationbodyofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Tremolet_Taking_into_Account.pdf.

[2] Tuck, L. et al. (2013), “Water Sector Regionalization Review. Republic of Moldova.”, http://www.danubis.org//files/File/country_resources/user_uploads/WB%20Regionalization%20Review%20Moldova%202013.pdf.

[33] UN (2015), Sustainable Development Goals, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

[19] UNDP (2009), “Climate Change in Moldova”, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/nhdr_moldova_2009-10_en.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2018).

[6] UNECE (2014), Environmental performance review, Republic of Moldova. Third Review Synopsis., UNECE, https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/Synopsis/ECECEP171_Synopsis.pdf.

[32] UNEP (2014), Environmental strategy years 2014-2023, https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/report/environmental-strategy-years-2014-2023.

[8] Verbeeck, G. (2013), Increasing market-based external finance for investment in municipal infrastructure, https://www.iwapublishing.com/sites/default/files/documents/online-pdfs/WUMI%208%20%284%29%20-%20Dec13.pdf.

[35] Verbeeck, G. and B. Vucijak (2014), “Towards effective social measures in WSS”, Towards effective social measures in WSS, https://1drv.ms/b/s!Anl6ybs2I7QGhdUX96FsaFC6JTUpIA.