This chapter provides an overview on the current trends that are leading to an increasing diversity of family forms and family life in Spain. Spain has the lowest total fertility rate among EU countries and many Spanish families are becoming smaller. Furthermore, the country has experienced a modernisation of the institution of the family in the last decades, which led to the liberalisation of marriage and divorce laws, more egalitarian gender roles, a wider acceptance of the diversity of family forms, and the emergence of new kinship roles. Across many dimensions, people in Spain benefit from well-being outcomes that are similar to or better than the OECD average. Yet, a significant share of the population struggles with challenges such as insufficient income and risk of poverty, unemployment and high housing prices. This is particularly true for households with children, which tend to be more vulnerable than other population groups.

Evolving Family Models in Spain

1. The changing profile of Spanish families

Abstract

The profile of the typical family is changing across the OECD, but even more drastically so in Spain. From being one of the countries with the highest fertility rates in Europe, Spain now has the lowest rate in the region, leading to decreasing family sizes. Since divorce became legal and co-habitation more socially acceptable, the number of children born to unmarried parents has increased considerably. At the same time, the share of mothers who are employed increased by more than 50% over the past two decades, though it remains below the OECD average. This chapter provides details on these and other trends that are leading to an increasing diversity of family forms and family life in Spain. It also describes how Spanish families fare in terms of their life satisfaction, poverty and ability to access housing.

The changing structure of Spanish families

Spanish society values families and family life highly, but the way that families look and live is changing. The country has undergone a process of individualisation in parallel with the maintenance of a strong sense of modernised family solidarity (Meil, 2011[1]; Meil, 2006[2]). Societal acceptance for family diversity in the form of new family models and a growingly multicultural society is also relatively high (Ayuso, 2019[3]).

Many Spanish families are becoming smaller

Spain has the lowest total fertility rate among EU countries. The total fertility rate – the synthetic average number of children that would be born to each woman if she were to give birth to children in alignment with the current age‑specific fertility rates – has been below both the EU and OECD averages since 1983. Only Korea among OECD countries has a lower total fertility rate: 1.0 compared to 1.3 in Spain, 1.5 across the EU and 1.6 across the OECD in 2018 (OECD, 2021[4]). The rate among Spanish nationals (1.17) is even lower than among foreign women living in Spain (1.59). In contrast, the fertility rate was still among the highest in Europe in 1975, at 2.8 children per women. There were slight rebounds during the economic boom in the mid‑2000s, enhanced by immigration flows and the higher fertility rates among first-generation immigrants (OECD/European Union, 2018[5]), but these changes were only temporary.

One of the main reasons for the low fertility rate is the postponement of childbearing. In Spain, the mean age of women at their first birth is 30.9 years, which is only a slightly younger age than in Italy (31.1) and Korea (31.6) (OECD, n.d.[6]). The extended period of young adults living in their parental home is one factor that contributes to later child birth. Young people often feel the need to complete their education, establish themselves on the labour market and save for home ownership first before leaving their parental home, given that rentals are often unavailable or unaffordable.

Actual fertility in Spain is below the desired level. This gap was already observed in the 1990s, when the observed total fertility rate of 1.2 was noticeably below the average desired number of children of 2.2 (Bernardi, 2005[7]). For women born between 1969 and 1973, the last Fertility Survey estimates the gap between the actual and potential fertility at 0.2 children per woman (Esteve and Treviño, 2019[8]).

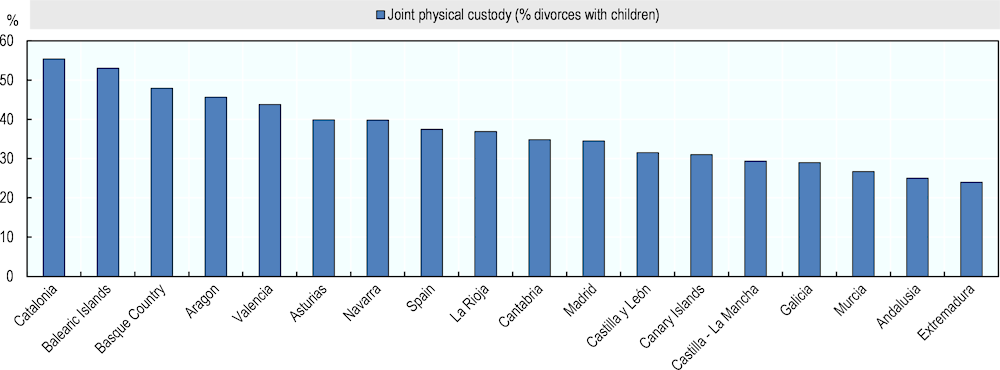

One of the contributing factors to this fertility gap are women who remain childless despite wanting to have children. The share of childless women drops from 95% among under‑25‑year‑olds to 19% among 40‑49 year‑olds (Figure 1.1). Among these childless women in their forties, more than half would still like or would have liked to have at least one child. In addition to fecundity and health problems – cited by a quarter among women in their forties – and not having a partner – cited by 22‑25% of childless women starting from age 30 –, economic and work-life balance reasons are very important, in particular among women in their thirties. An adverse economic environment with low economic growth and high unemployment is negatively associated with fertility, suggesting that economic stability and expectations for the future impact couples’ decisions to start or grow their families (Hoorens et al., 2011[9]).

Figure 1.1. More than one in two childless women in their forties would have liked to be a mother

Note: The statistics are based on the 2018 Fertility Survey.

Source: Esteve and Treviño (2019[8]), The main whys and wherefores of childlessness in Spain, https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/worpap/2019/204270/perdem_a2019m04n015iENG.pdf.

In addition to people who remain unwillingly childless, parents may also have fewer children than they would like to. More than 70% of women would like to have at least two children, but fewer than 30% actually do (Sosa Troya and Mahtani, 2019[10]). In heterosexual couples in which the woman is 20‑44 years old, the couples in which both have high educational attainments and stable jobs are more likely to have two children. Otherwise, for couples where the two partners have differing circumstances, stable employment is a more decisive factor than a high educational attainment for having a higher fertility; and a better woman’s employment position is most conducive to a higher fertility (Bueno and García-Román, 2021[11]).

Children are present in a slightly larger share of households than across the EU on average, but there are fewer large families. In 2019, about one‑third (32.5%) of households had at least one child member. This share is somewhat lower than the maximum of 38.7% observed in Ireland, but above the EU average of 28.8% and significantly higher than the shares observed in countries such as Sweden, Germany and Finland (22.9‑21.0%). Among households with children, half are single‑child households (50.0%, compared to 47.4% across the EU). Fewer than one in ten (9.1%) are households with at least three children. Despite the strong orientation of Spanish family protection policy towards the support of large families (see Chapter 2), this share is hence lower than the EU average of 12.7% and those in countries such as France (18%), Finland (20.3%) and Ireland (25.2%) (Eurostat, 2020[12]).

Families are becoming more diverse

The process of secularisation (González and Requena, 2008[13]) and the change in values and attitudes of the Spanish population have paved the way for the modernisation of the institution of the family. It lead to the 2005 liberalisation of marriage and divorce laws, to more egalitarian gender roles, to a wider acceptance of the diversity of family forms, and to the emergence of new kinship roles. This section discusses how the prevalence of unmarried, blended and single parent families has evolved and how views about what constitutes a family have changed.

Children living in diverse families

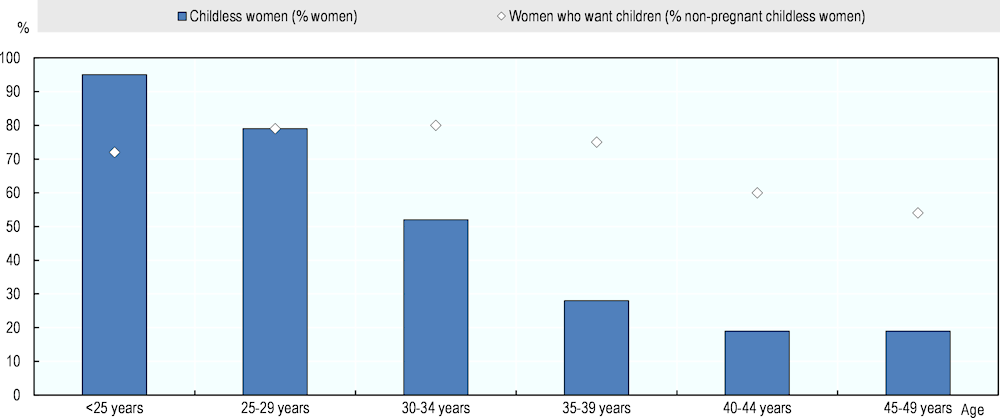

While the share of traditional nuclear family has declined over time due to legal and societal changes, it nonetheless remains the predominant family model. In 2018, 82.8% of minor children were living either with both of their parents or within a reconstituted family (i.e. with two adults who were both parents), 15.6% with a single parent and 1.5% in other arrangements (Figure 1.2). These shares are similar to OECD and EU averages. Compared to 2004, the proportion of minor children living with married parents declined by 7 percentage points; while the shares living with cohabitating parents or a single parent rose by four and 7 percentage points, respectively. While about one in ten children under the age of six lives with a single parent – with the absolute majority living with their mother – the number rises to more than one in seven among six to 11 olds and more than one in five among 12 to 17 year olds.

Figure 1.2. About three‑quarters of minor children in Spain live in households with two parents

Note: Data for Mexico refer to 2010, for Australia to 2012, for Japan to 2015, for Canada and Iceland to 2016, and for France, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Turkey, the Slovak Republic, and Switzerland refer to 2017. For Japan and Mexico, children aged 0‑14 ‘Parents’ generally refers to both biological parents and step- or adoptive parents, who could either be married or cohabitating. ‘Living with a single parent’ refers to situations where a child lives in a household with only one adult who is considered a parent. ‘Other’ refers to a situation where the child lives in a household where no adult is considered a parent.

Source: OECD (n.d.[6]), Indicator SF1.2 “Children in Families”, OECD Family Database,

http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/SF_1_2_Children_in_families.xlsx

One reason for the declining share of married families is the increasing number of divorces over the last several decades, though there has recently been a decline. The crude divorce rate increased by 0.3 per 1 000 people each decade between 1980 and 2000, but the rise accelerated afterwards. In 2019, with 91 645 registered divorces, Spain’s crude divorce rate was 1.9 per 1 000 inhabitants (INE, 2020[14]). This rate roughly corresponds to the EU‑28 average and France and Portugal’s rates, but it is much higher than in Italy (1.5) and Greece (1.0) (OECD, n.d.[6]). The steady fall in the number of marriages since the beginning of the 21st century partially explains the recent drop in the number of divorces (6.4% between 2017 and 2019). In the majority of divorce cases of heterosexual parents, mothers are still granted custody (58.1%).

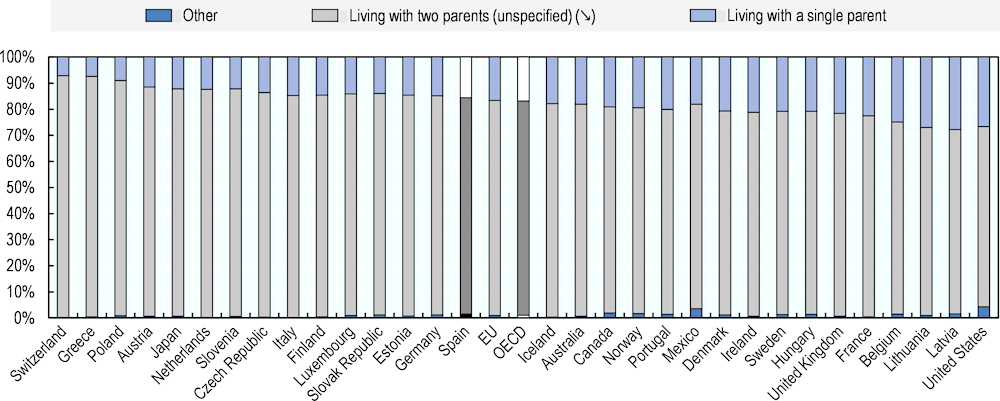

Despite its relatively recent introduction in 2005, joint physical custody is now granted in 37.5% of cases (INE, 2020[14]). However, the national average hides important regional differences that may be related to different patterns of maternal employment (Figure 1.3). The impact of the 2005 change in law was greater than expected because from 2010 on, a few North-eastern regions with civil legislation powers such as Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Navarra and the Basque Country passed laws that established a legal presumptions of joint physical custody (Flaquer, 2015[15]; Solsona and Ajenjo, 2017[16]; Solsona et al., 2020[17]).

Figure 1.3. The share of joint physical custody is twice as large in some regions than in others

Another reason for the declining share of married families is the increasing number of children born out of wedlock. Since 2000, the share of children born whose parents were not married has nearly tripled, from 17.7% to 47.3% in 2018.1 A higher share of college‑educated women compared to women with lower educational attainment are cohabitating rather than being married, but among cohabitating women, those with lower educational attainment are more likely to give birth than those with intermediate or higher education. Separations of unmarried couples with children have been soaring in the last few years. An estimate for 2017 suggests that they represent 47% of the sum of separations and divorces (Flaquer and Becerril, 2020[18]; Flaquer and Becerril, 2020[19]). In Spain as well as elsewhere, unmarried couples are more likely to separate than married ones. Their fragility can be not only explained by the weakness of partners’ commitment resulting from a lack of legal bond, but also by the stress of economic difficulties (Castro-Martín and Seiz, 2014[20]). Although little information is available about the legal features of separations filed by unmarried parents, a crucial finding is that 59% of separations are contested compared to only 23% of divorce cases.2

Divorces and separations can lead to reconstituted or blended families when parents find a new partner, but comparable data on this phenomenon is limited. According to a 2013‑14 study based on the Health Behaviour of School Aged Children,3 6% of young adolescents aged 11 to 15 were living in such a family. This prevalence was below the EU‑25 average of 8% and the share in France (13%). A 2016 study based on the 2011 Spanish Census suggests that among heterosexual couples that live with a child under the age of 18, one of the members of the couple is not a parent of the minor child in 7.4% of cases (Ajenjo-Cosp and García-Saladrigas, 2016[21]). In about half of reconstituted families, there were no common children. The same study’s estimates for the prevalence of reconstituted families based on the EU-LFS data were considerably lower, though the authors note that the survey’s suitability of this analysis is limited. Nevertheless, the EU-LFS analysis allows an international comparison, which once again places Spain in the lower-middle among European countries in terms of the prevalence of this family form.

Social attitudes on family and family diversity

People in Spain and elsewhere value family very highly. According to the last wave of the European Values Survey (EVS/WVS, 2021[22]), at 88% and 86%, the percentage of Spaniards who considered their family as very important in their life and as trusting them completely are equal to the cross-country averages. A higher share of people in Spain maintain more‑than-weekly contact with their parents or children: 78% and 87%, compared to the cross-country averages of 61% and 67%. Although nine in ten people in Spain and European countries overall consider that having children is an important element of a successful marriage or partnership, having children is no longer considered a key element for achieving happiness, and women are not stigmatised for not having children. The decision to have children is considered a private matter. Parenthood without being married is widely accepted (by 73% of people) (ISSP, 2012[23]), as is motherhood without being in a partnership (86% approve when a woman without a partner decides to have a child) (CIS, 2016[24]). Eighty-eight percent approve when two persons with different racial background decide to have children (CIS, 2016[24]).

The understanding of marriage has also deeply changed. A consensual conception of partnership, away from the institutional understanding of marriage, has emerged during the last decades and become dominant in the population as a whole. Attitudes towards cohabitation moved away from being considered scandalous towards being tolerated and finally even recommended as a trial period before marriage. In fact, more than eight in ten including many older and religious people agree with the statement that it is alright for a couple to live together without intending to marry (ISSP, 2012[23]). In most cases, the openness towards cohabitation does not imply a rejection of marriage. Nonetheless, one‑third of Spanish respondents considers marriage an outdated institution, a proportion that is among the highest in the surveyed European countries and significantly higher than the average of 20% (EVS/WVS, 2021[22]). Attitudes towards divorce have also changed profoundly. Three quarters of the population now see it as the best solution when a couple cannot work out their marriage problems (ISSP, 2012[23]).

Attitudes towards same‑sex couples have profoundly changed. While conservative and religious individuals initially rejected the introduction of the so called “egalitarian marriage” in 2005, it is widely accepted today. In a 2016 survey, 76% of respondents supported that “two persons of the same sex could marry” (CIS, 2016[24]); and by 2019, 86% of Spaniards (compared to the EU average of 69%) thought that “same sex marriages should be allowed throughout Europe” (European Commission, 2019[25]). The extension of the right to marry automatically granted the same rights to same‑ and opposite‑sex married couples, including the right to adopt children jointly. Views on same‑sex parenting remain more split, even though it is still a majority – 64%, to be precise – that considers these couples as equally competent parents as heterosexual ones (EVS/WVS, 2021[22]). This share is smaller than in Nordic countries (around 75%), but substantially larger than the EU average (37%). Older, less educated and more religious people as well as men and people living in rural areas support this type of family much less frequently.

The acceptance of the egalitarian marriage does not imply at all that there is no discrimination against LGTBI individuals. As a recent survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020[26]) shows, 21% and 38% of LGTBI citizens living in Spain have ever felt discriminated against in employment matters and other areas of life, respectively; and only one in two among them revealed their sexual orientation to most or all of their family members. These shares are almost identical to the EU28 averages.

The share of families with a migrant background is increasing

Until the 1980s, Spain was predominantly a country of emigration, but has become an important destination for immigrants since then. The first massive immigration wave started in the last years of the 20th century, in a context of economic liberalisation and growth, high demand of cheap labour and high acceptance of employers hiring irregular workers, particularly in the construction, agriculture and domestic services sector. Roughly ten years later, foreign-born individuals grew to represent around 14% of the population and 17% of the labour force, with important regional differences (Flaquer and Escobedo, 2009[27]). . Since 2010, the number of foreigners with legal residence initially descended but then grew again significantly, over the 2018 to 2020 period (from 4.7 million residents in January 2018 to 5.2 million in 2020, after having reached a peak of 5.8 million individuals in 2011) (INE, 2021[28]).

Spain’s immigrant population is now relatively large and comes from a variety of countries. In 2019, the foreign-born population share (including both regular and irregular immigrants as long as they recorded in municipal registers) of 14% placed Spain in the middle of OECD countries in terms of immigrant concentrations, though still far below the rates of close to 30% observed in Australia and Switzerland (OECD, 2021[29]). Among the population with a foreign nationality, Romanian, Moroccan, British, Italian, Chinese and Bulgarian citizens are the largest groups. Moreover, over the last decade, for example more than 220 000 Moroccans, 190 000 Ecuadorians and 150 000 Colombians gained Spanish citizenship (MITRAMISS, 2021[30]).

Immigration to Spain is neither predominantly male nor female. Currently, 47% of registered foreigners are women; and 51% of the inflow of new immigrants in 2018 were women. This compares to an OECD average of 44% among new arrivals in 2018. Only Australia and the United States have a very slightly higher share of women among immigrants; while in some countries, such as Slovenia, Latvia and Lithuania, the share of men exceeds 70% (OECD, 2020[31]).

A higher share of immigrant-headed households are families than among native‑born households. This is true for Spain as well as on average across the EU and the OECD. In 2016, among immigrant-headed households (meaning that at least one of the household heads was born abroad), 5.2% and 37.6% were single‑ or dual-parent households, 3.8 and 13.4 percentage points higher than among native‑born headed households. These differences to the composition of native‑born households was even larger than on average across the EU and OECD. However, the household size of immigrant-headed households is only slightly higher than among native‑headed households (2.75 compared to 2.44, a similar difference as across OECD countries) (OECD/European Union, 2018[5]).

Shifts in Spanish family life

The dual-earner family model became dominant

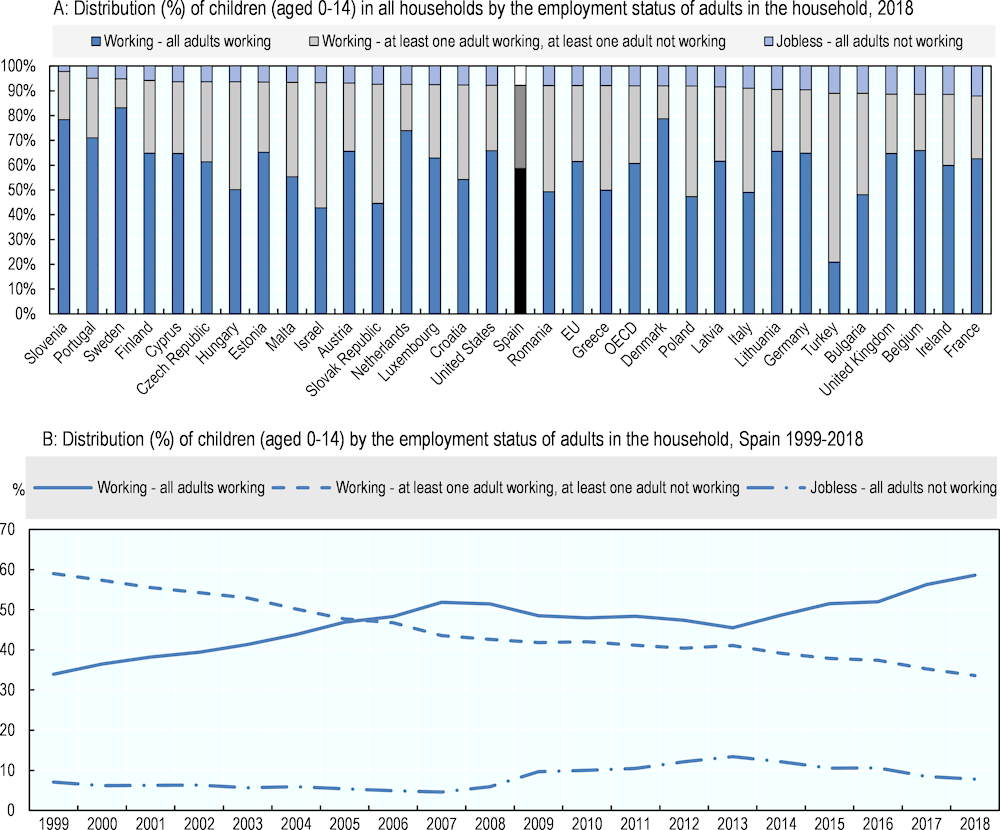

Since the turn of the century, the dual earner family model has become more prevalent in Spain. Starting at 34% in 1999, the share of children under age 15 in households where all adults are working rose to 58.6% by 2018 (Figure 1.4). However, the share remains below the EU and OECD averages (61.5% and 60.7% respectively), and substantially below the shares observed in Denmark, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden. Unlike in countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and most notably the Netherlands, where one half to three‑quarters of dual earner couples have one full-time and one part-time worker, this family situation applies to fewer than a quarter in Spain. The share of children living in jobless households experienced a surge in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (13.4% in 2013) and has yet to return to its pre‑crisis levels. In 2018, more than nine out of ten of children in Spain (92%) were living in households with at least one adult working, a situation comparable to the EU and OECD averages.

Figure 1.4. The dual earner family model is dominant in Spain

Note: Data for Turkey refer to 2013, and for Israel to 2017. For Israel and the United States, data refer to children aged 0‑17. For the United States, data cover children living with at least one parent and refer to the labour force status of the child’s parent(s) only, and refer to whether or not the child’s parents are active in the labour force, as opposed to in employment.

Source: OECD Family Database, Chart LMF1.1.A, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

In single‑parent homes, the share of working parents is higher in Spain than on average across the EU and the OECD. In 2018, 74% of children aged 14 years or younger living with a single parent had their parent working either part- or full-time, compared to the EU average of 70.3% and the OECD average of 69.6%. In about a fifth of these cases, the parent was working part-time. The pattern that the majority of working single parents do so full time is common across European countries, with the exception of the United Kingdom.

The rising share of dual-earner households tracks increasing maternal employment rates. Between 1999 and 2019, the share of mothers with at least one child under the age of 15 who were working rose from 42.8 to 67.5%. Over the same period, attitudes towards maternal employment became noticeably more positive: while in 2000, 42% of respondents in Spain to the World Value Survey still agreed with the statement that pre‑school children suffer when their mother works outside the home, by 2017, this share had decreased to 25% (EVS/WVS, 2021[22]). This maternal employment rate nonetheless is 5.5 percentage points below the EU average.

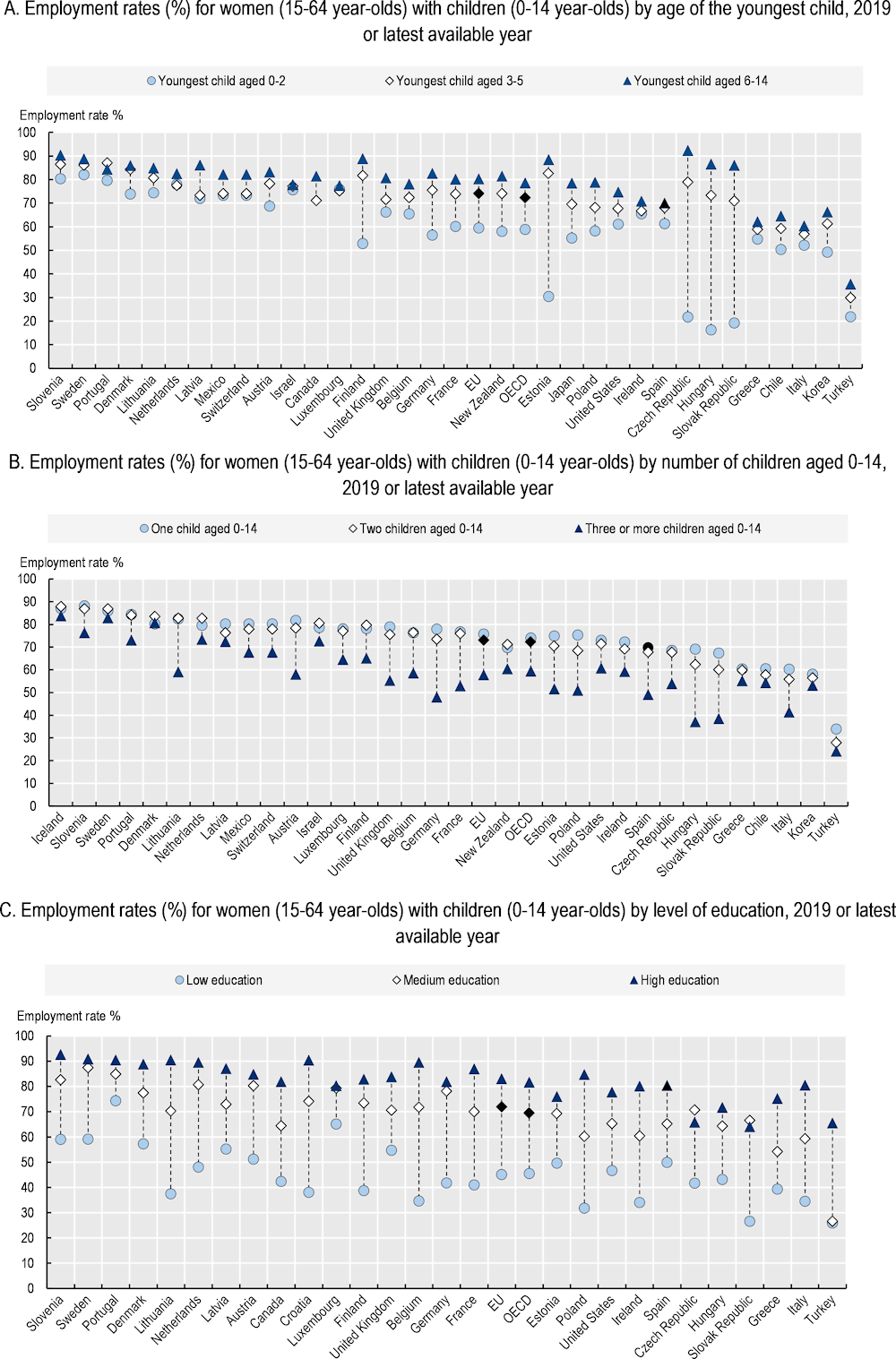

The age of the youngest child and the mother’s education level have less of an impact on maternal employment rates in Spain than in most EU countries, but the number of children has a larger impact. Comparing the rates among mothers whose children are of school age with those whose youngest is under the age of three, the difference amounts to 8.9 percentage points in Spain compared to 20.8 percentage points on average across the EU (Figure 1.5, Panel A). The gap is still substantially larger in countries such as France and Germany, while the gradient is much less perceptible for example in the Netherlands, Sweden or Portugal. Except in Denmark or Sweden, having three or more as opposed to one or two children is associated with a drastically lower maternal employment rate in all selected EU countries. In the case of Spain, the maternal employment rate of mothers with two children is 2.1 percentage points lower than among mothers with one child (Figure 1.5, Panel B). But among mothers with three or more children under the age of 14, the employment rate is 18.4 percentage points lower. Finally, a mother’s education level is an important influencing factor in whether she is employed or not. In each of the selected European countries, more than 80% of mothers with a tertiary degree are employed, and the share even reaches 86.1% in Sweden (Figure 1.5, Panel C). Maternal employment falls in all countries for low educated mothers, except in Portugal. In the Spanish case, at 49.9%, the employment rate of mothers with less than an upper secondary degree is higher than the EU average (45.1%), while the rates for those with upper secondary and tertiary degrees are below the EU average.

Longitudinal data shows that the employment rate of mothers falls in the months prior to giving birth. A representative sample of Spanish Social Security registered labour trajectory records of individuals who became parents for the first time in 2003 showed that a third of mothers were registered unemployed at some point in the three years after giving birth (Escobedo, Navarro and Flaquer, 2007[32]). At 20%, the share is highest in the first year, with a peak of cases just after the end of maternity leave, and did not return to their prior employment situations afterwards. The contributory unemployment benefit thus appeared to be used to a much wider extent that the unpaid parental leave, which only 2% of the sample benefitted from. The employment situation of fathers, in contrast, did not change much. Only one of every five fathers had any spell of registered unemployment over the same three‑year period, and they were on average half as long as mothers’ unemployment spells. Complementary qualitative research conducted in the same period indicated that some mothers, in particular those who worked in less qualified jobs, opted for paid unemployment when it was possible, for example after completing a temporary contract. This allowed them to stay at home with their child while they could not afford the unpaid parental leave scheme (Flaquer and Escobedo, 2020[33]).

Generally, the transition to fatherhood has been associated with the consolidation of men’s professional status; while the transition to motherhood has been associated with an intensification of the caregiver role, which may affect the professional status to a lesser or greater extent. This specialisation of roles in terms of gender tends to occur after the birth of a first child and often lasts until the child attends early childhood care. Whether or not the impact on maternal employment is temporal depends to a large extent on the accessibility, cost and quality of early childhood education and care services, but also on the father’s involvement in care tasks.

Figure 1.5. Maternal employment rates vary by the age of the youngest child, the number of children and the education of the mother

Note: For Japan, data cover all women aged 15 and over, and for Korea married women aged 15‑54. For Canada, Korea and the United States, data refer to women with children aged 0‑17. For Canada, the age groups for the age of youngest child are 0‑5 and 6‑17, for Israel 0‑1, 2‑4 and 5‑14, for Korea 0‑6, 7‑12 and 13‑17,and for the United States 0‑2, 3‑5 and 6‑17. Data for Japan refer to 2018, for Chile to 2017 and for Turkey to 2013. ‘Low education’ corresponds to a highest level of educational attainment at ISCED 2011 levels 0‑2 (early-childhood education, primary or lower secondary education); ‘medium education’ reflects a highest level of educational attainment at ISCED 2011 Levels 3‑4 (upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education); and ‘high education’ corresponds to a highest level of educational attainment at ISCED 2011 Levels 5‑8 (short-cycle tertiary education, bachelor or equivalent, master or equivalent, doctoral or equivalent).

Source: OECD (n.d.[6]), “LMF1.2 Maternal employment”¸ OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/LMF_1_2_Maternal_Employment.xlsx.

Fathers are spending more time with their children and on household chores

Women have long had more responsibilities in unpaid care and housework than men did, but while this continues to be true, there are also indications that patterns have started to change. In Spain, the increased availability of paternity leave and joint physical custody starting in 2007 appear to contribute to higher involvement by fathers (Flaquer and Escobedo, 2020[33]; Meil, 2011[34]). The 2008 crisis, which led to higher male unemployment, also appeared to play a role in this higher involvement (Castrillo et al., 2020[35]; Flaquer et al., 2019[36]). Changes in the gender gaps in time use are higher when mothers are employed and have higher educational attainment. The narrowing of the gap is also more apparent in certain family types, such as in step families in which the mother was previously a single parent.

The most recent time use survey in Spain dates from 2009, but future waves may reveal an impact of the 2019 leave reform. In between the 2002 and 2009 survey waves, the 20‑minute decline in the time women of all age groups spent on household and family exactly corresponded to the 20‑minute increase men spent on these tasks (INE, n.d.[37]). But the gap nonetheless remained very substantial: women spent 244 minutes on these tasks and men 110 minutes. The 2019 reform rendered the leave for mothers and fathers individual, equal and non-transferable. Groups advocating for this reform hope that this will translate to increased involvement of fathers in the care of children and household tasks, as happened in other countries (see Duvander and Jans (2009[38]) for the Swedish case and Eydal and Rostgaard (2014[39]) on Nordic welfare states). However, comparative research evidence (O’Brien and Wall, 2017[40]; Meil, Rogero-García and Romero-Balsas, 2017[41]) indicates that substantial effects only occur when fathers are the only parent who is on leave for at least one uninterrupted month. This way, they become primary caregivers and are not in a secondary role of “helping” mothers. As the new Spanish regulation allows fathers and mothers to take all of the leave concurrently as well as part-time, it will be useful to monitor if the expected impact on paternal involvement varies according to the different patterns of leave use.

Inter-generational support is evolving but remains important

In spite of individualisation trends, family solidarity remains high and characteristic of the Spanish family system (Meil, 2011[34]). Every time Spain goes through an economic crisis, the family re‑emerges as a very important support system. After the 2007 crisis, the family played a crucial role in smoothing out its impacts; and during the ongoing COVID‑19 crisis, Spanish society once again takes refuge in family relationships (Escobedo et al., 2021[42]). Nonetheless, extended family solidarity and intergenerational support are evolving towards a more elective direction, with higher expectations placed in public care services and benefits.

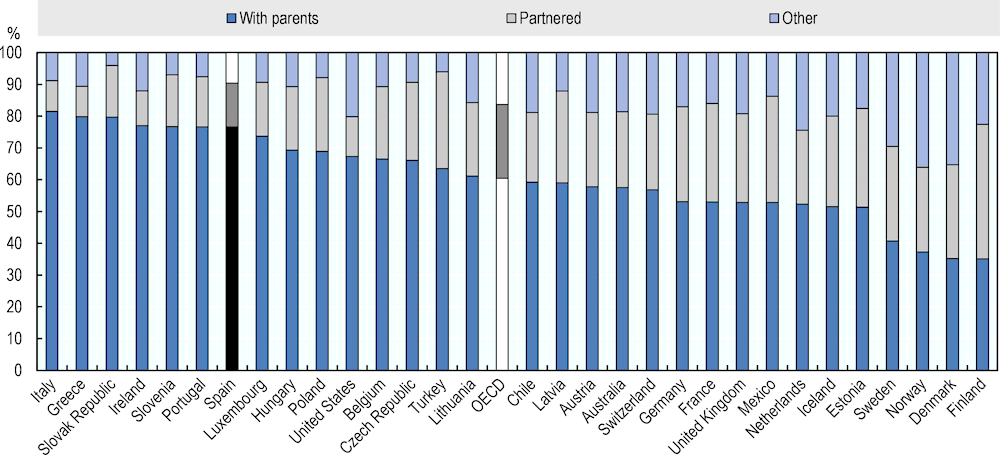

Many adult children do not move out of their parental home until they are older than is typical in many other OECD countries. The share of 15‑29 year‑olds who were living with their parents was equal to 76.6%, compared to 60.4% across the OECD (Figure 1.6). However, there are a number of other OECD countries where an even bigger share of youth continue to live at home, including Italy, Greece and the Slovak Republic. Young people even leave home later than previously: In 2007, about 30% of 16‑29 year‑olds had left their parents’ home. The decreasing share likely is due both to the increased youth unemployment as a result of the Global Financial Crisis as well as to rising costs in the rental market. Even among 30 to 40 year olds, 29% were still living with their parents (Consejo de la Juventud de España and López Oller, 2020[43]). The share of emancipation among 16‑29 year‑olds is noticeably lower among men (14.8%) than among women (22.8%). Only one in ten young women who have left their parental home live by themselves, while nearly one in four young men do. While the low share of youth leaving their parental home is in part due to structural difficulties (Escobedo et al., 2018[44]; Moreno, 2012[45]), it also contributes to a strong sense of family co‑operation and solidarity.

Figure 1.6. Only one in four young Spaniards no longer lives with his or her parents

Note: Data refer to 2016 for Iceland, Ireland, Mexico, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, and 2015 for Turkey. No information for Japan, Korea and New Zealand due to data limitations. ‘Other’ includes individuals who are living alone, as a single parent or with other adults than their parents or a partner.

Source: OECD (2021[46]), “HM1.4 Living arrangements by age groups”, OECD Affordable Housing Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/HM1.4-Living-arrangements-age-groups.xlsx.

Care in family networks is assured through a combination of formal and informal care services that is more equally shared between generations and men and women than was the case in prior decades. In 2017, nearly one in three seniors who were living in private households were living in one that did not consist of one or more seniors. This can include people over the age of 65 living with a younger partner, but could also include the older person living with one of their children or another family member. The cross-country OECD average was equal to 25.6%; but in some countries such as Chile and Mexico, the share was close to or even exceeded 60%. Seniors who are living with their adult children do not necessarily need care; and in fact the highest share of informal carers to parents in European countries (as revealed by the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe) is among near-seniors themselves (OECD, 2019[47]). Grandparents often contribute to the provision of care and support for their grandchildren. Often, they complement formal childcare and education, either on a weekly basis or to make ends meet during the long Spanish school holidays.

Vulnerabilities of Spanish families

Across many dimensions, individuals living in Spain benefit from well-being outcomes that are similar to or better than the OECD average. The average reported life satisfaction on a ten‑point scale is almost identical to the OECD average (7.3 versus 7.4). Few employees have to work very long hours and people can devote slightly more time to leisure, personal care and social interactions than in other OECD countries on average. A slightly smaller share of the population reports not having someone they can count on in times of trouble and the life expectancy is among the highest across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[48]). Yet, alongside these rather positive outcomes, a significant share of the population struggles with challenges such as insufficient incomes and risk of poverty, unemployment and high housing prices, and households with children tend to be more vulnerable than other population groups. The poverty rates presented in this chapter refer to post-transfer income. Chapter 2 takes a more detailed look at pre‑transfer poverty rates and the role of the welfare state in addressing poverty.

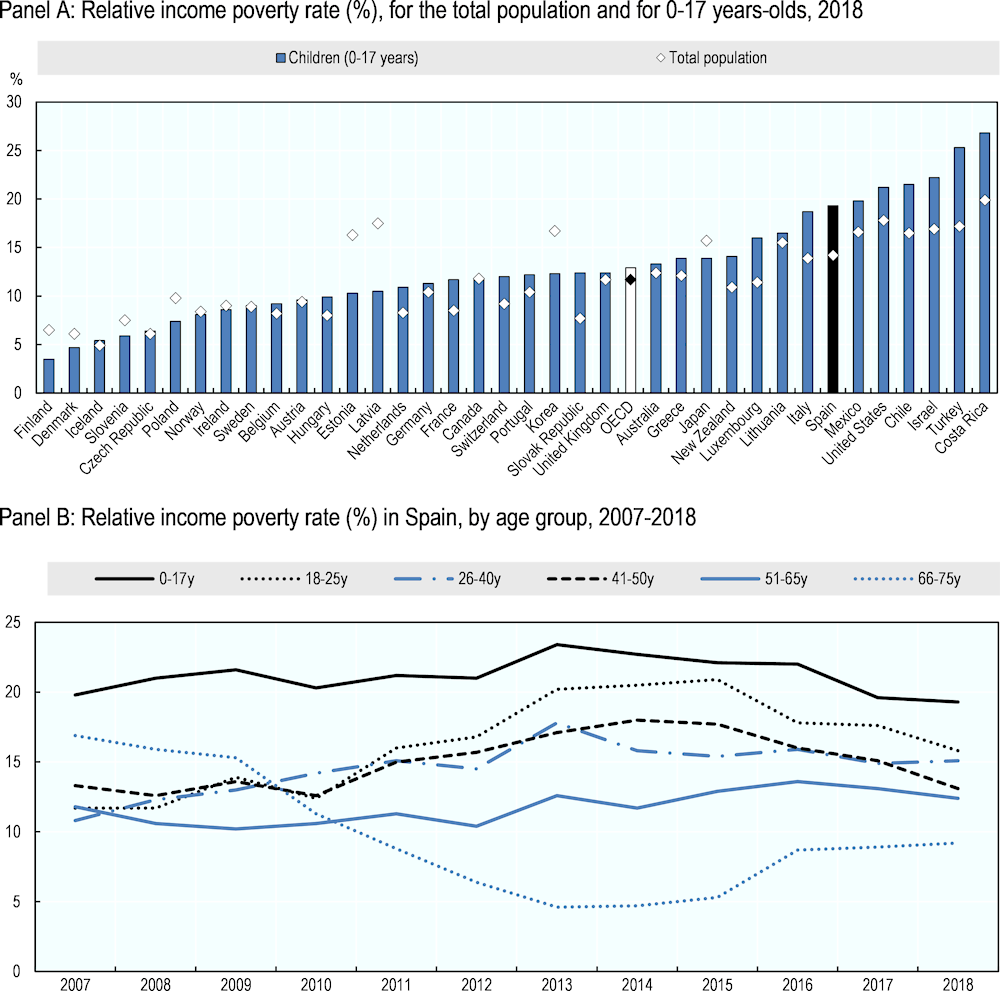

High rates of child poverty

In 2018, nearly one in five children (19.3%) lived in relative income poverty in Spain, compared with 12.9% in OECD countries on average (Figure 1.7, Panel A).4 Spain ranks highest amongst European OECD countries, and its child poverty rate is more than five times higher than the rate in Finland, the OECD country with the lowest child poverty rate. Children in Spain face higher poverty risks than other population groups, as is the case most OECD countries. Relative income poverty for the total population in Spain (14.2% in 2018) comes closer to the OECD average of 11.7% than is the case for children, though Spain remains in the upper third ranking of OECD countries. During the 2010s, relative income poverty rose particularly among young and middle age groups (18‑50 years), and to a lesser extent among children, whereas poverty rates declined considerably for the age group 66 and over (Figure 1.7, Panel B). Child poverty peaked at 23.4% in 2013 as a result of the global financial crisis, but has been declining gradually since then. However, children continue to face the highest poverty risk in Spain.

Being exposed to income poverty is harmful to all members of a family, but it is particularly so for children (Thévenon et al., 2018[49]). Income poverty dramatically increases the risk that children will experience some kind of material deprivation. For example, income‑poor school-aged children in Spain are twice as likely to live in low-quality housing as non-poor children (Table 1.1); and three times as likely not to eat fruits, vegetables or proteins every day and not to participate in regular leisure activity. They are nearly six times more often exposed to multiple and severe deprivations (defined as children lacking at least four items) than non-poor children. Similar outcomes are found in France and the United Kingdom. That being said, the persistence of low-income status across generations may be lower in Spain than in a number of other OECD countries. An analysis of the intergenerational earnings elasticity between fathers and sons in the early 2010s found that intergenerational mobility for the bottom 10% of the father’s earnings distribution was higher in Spain than in nine out of 13 countries included in the analysis (OECD, 2018[50]).

Figure 1.7. Nearly one in five children lives in poverty in Spain

Notes: Data are based on equivalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The poverty threshold is set at 50% of median disposable income in each country. Working-age adults are defined as 18‑64 year‑olds. Children are defined as 0‑17 year‑olds. Data are for 2014 for New Zealand; 2015 for Japan and Turkey; 2017 for Chile, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands (provisional), Switzerland and the United States.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database, http://oe.cd/idd.

Table 1.1. Income poverty dramatically increases the risk of material deprivation

Material deprivation rates for children aged 6 to 15 across different dimensions, 2014

|

Spain |

France |

United Kingdom |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

Non income‑poor children |

Income‑poor children |

Total |

Non income‑poor children |

Income‑poor children |

Total |

Non-income‑poor children |

Income‑poor children |

|

|

Housing |

31.4 |

23.5 |

48.3 |

28.4 |

23.6 |

51.4 |

33.7 |

30.3 |

47.3 |

|

Nutrition |

8.0 |

4.4 |

15.6 |

10.8 |

8.4 |

22.2 |

11.1 |

10.2 |

14.9 |

|

Leisure |

41.8 |

26.7 |

74.5 |

30.2 |

24.0 |

59.8 |

43.4 |

38.7 |

62.3 |

|

Education |

17.2 |

9.4 |

34.0 |

13.0 |

9.4 |

30.1 |

10.7 |

8.8 |

18.4 |

|

Social environment |

22.2 |

19.7 |

27.7 |

25.7 |

23.0 |

38.7 |

26.9 |

25.4 |

33.0 |

|

Deprivation in 1 basic item at least |

63.5 |

52.8 |

86.5 |

62.1 |

56.5 |

88.4 |

69.7 |

66.1 |

84.6 |

|

Severe deprivation |

18.0 |

7.2 |

41.4 |

12.7 |

7.7 |

36.3 |

16.4 |

14.3 |

25.1 |

Note: Severe deprivation refers to children lacking at least four items. See Thevenon et al. (2018[49])for a definition of the variables.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey 2014.

A recent OECD paper analyses the drivers of child poverty in detail for Spain and several other OECD countries (Thévenon et al., 2018[49]). The analysis shows that differences in trends regarding paternal and maternal employment rates and job quality are the most important factors explaining cross-national differences in the evolution of the income for low-income families. For instance, the income growth provided by the increase in the employment rate of mothers in Denmark and Sweden suggests that family-friendly employment policies can pave the way for significant reductions in child poverty. By contrast, the decline in the proportion of children with a working father contributed to a sharp drop in income in Spain between 2007 and 2014. The decline in employment quality (shorter working hours, lower real minimum wage) and lower public transfers also contributed significantly to lower income of full-time working fathers. The impact was considerably stronger for poor families than for middle‑income families. Spain’s changes in family structure and the increase in the proportion of children with a single parent also contributed to a drop in income, but to a lesser extent than the labour market outcomes of parents. Social benefits played a rather limited role in mitigating the effect of the global financial crisis.

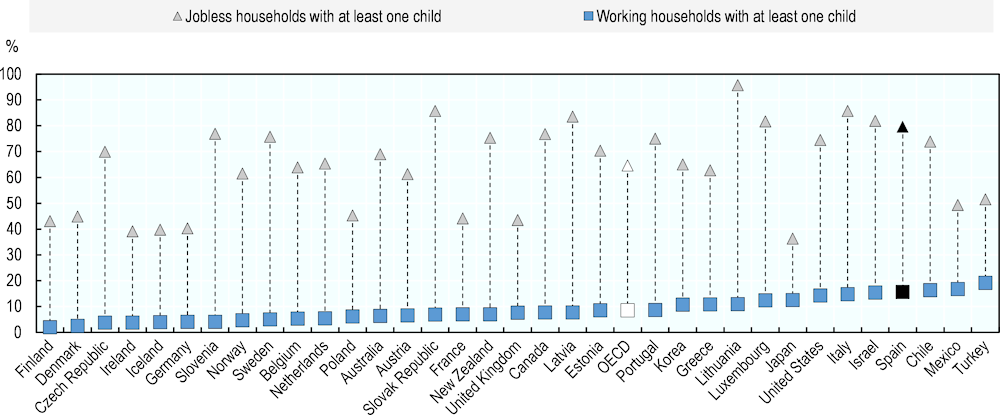

Poverty risk by parents’ employment status

The most significant determinant of poverty among families is the employment status of the parents. On average across the OECD, individuals living in jobless households with at least one child are nearly eight times more likely to be income‑poor than working households with at least one child (Figure 1.8). The difference between these two groups is smaller in Spain (5 times), mainly due to the relatively high relative income poverty rate among working households. In 2018, eight out of ten individuals living in jobless households with children (79.6%) were income‑poor in Spain. This share is significantly higher than the average among OECD countries (64.5%), placing Spain third highest among OECD countries. However, even among members of working households with children, 15.6% live in relative poverty in Spain, compared with the 8.5% OECD average. This share is the second highest among OECD countries and the highest among EU OECD. For comparison, 5% or less of individuals living in working households with children are income‑poor in countries like Germany, Ireland and the Nordics.

Figure 1.8. Poverty rates in Spain among jobless and working households are both high compared with other OECD countries

Notes: Data are based on equivalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The poverty threshold is set at 50% of median disposable income in each country. Working-age adults are defined as 18‑64 year‑olds. Children are defined as 0‑17 year‑olds. Data for New Zealand to 2014, for Japan and Turkey to 2015, for the Netherlands to 2016, for Chile, Denmark, Germany, Iceland, Ireland and Italy to 2017.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database, http://oe.cd/idd.

Poverty risk by family structure

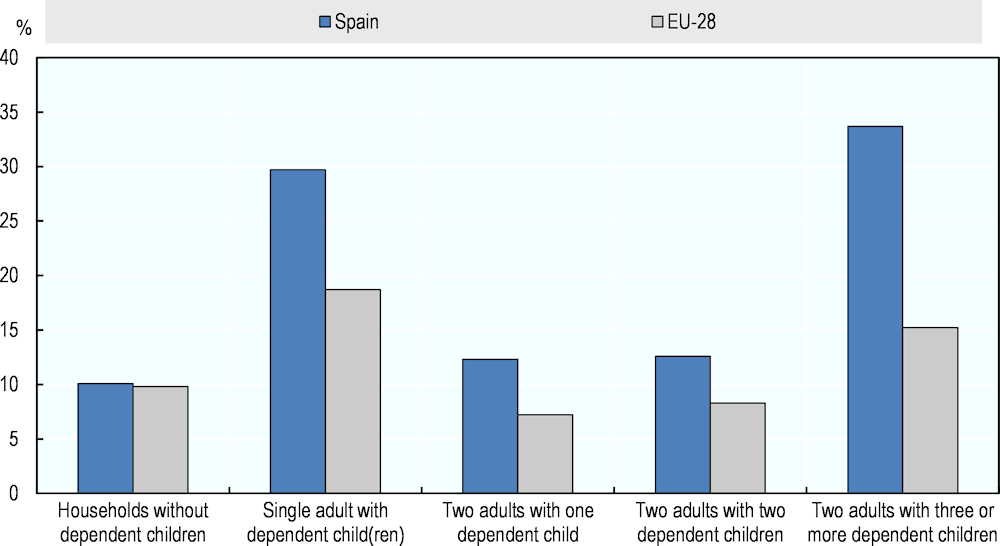

Family structure is another factor that influences the risk of poverty, with households with children in general and large and single‑parent family being at particular risk. Whereas the poverty rates of individuals in households without dependent children are quite similar in Spain and the EU (around 10% in 2019), there is a noticeable gap of nearly 7 percentage points between Spain’s and EU’s poverty rates for those in households with dependent children, reaching 17.1% and 10.5% respectively (Figure 1.9). The gap in relative poverty rates between Spain and the EU average is nearly 20 percentage points for households with two adults and three or more children (Figure 1.9). One in three members of large families live in relative poverty in Spain, compared to only one in eight members of families with one or two children. Although the high poverty rate among large families has been well-known for at least two decades and Spanish family policy has a strong focus on large families, advances in reducing poverty have been very limited. Relative income poverty rates are also high among single‑parent families in Spain (29.7%), and the gap with the EU average is considerable (11 percentage points).

Figure 1.9. Poverty rates are most prominent among large families and single‑parent families

Note: Households with less than 50% of median equivalised income are considered at risk of poverty.

Source: Eurostat (2021[51]), At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold and household type – EU-SILC and ECHP surveys, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_li03&lang=en.

In addition, children living in households where one of the adults has child support obligations may in reality experience a higher risk of poverty than the data are capturing. Poverty estimates assume that all income of a household member are shared within that household, rather than flowing to another household (Miho and Thévenon, 2020[52]). Households that receive regular child support payments count these among their income. However, if payments arrive irregularly, they would not be taken into account in the poverty estimations. In addition, parents who do not live with one or more of their children but who are in regular contact with them have additional costs far in excess of the proportion of time the child spends with them, such as an additional room in their home.

A weak labour market

The weak labour market in Spain greatly affects families and children. Even prior to the COVID‑19 crisis, unemployment rates were high in Spain. The country had been hit hard by the global financial crisis and the recovery process had been slow. In 2019, 14.2% of the Spanish labour force was unemployed, the second highest rate in the OECD (whose average stood at 5.6%), after Greece. The economic crisis resulting from the COVID‑19 pandemic further pushed unemployment rates upwards, reaching 16.0% in January 2021 (OECD average: 6.8%). Unemployment rates in Spain and across the OECD tend to be higher among women than among men, though the average gap across the OECD is considerably smaller at 0.4 percentage points compared to 4.0 percentage points in Spain in January 2021.

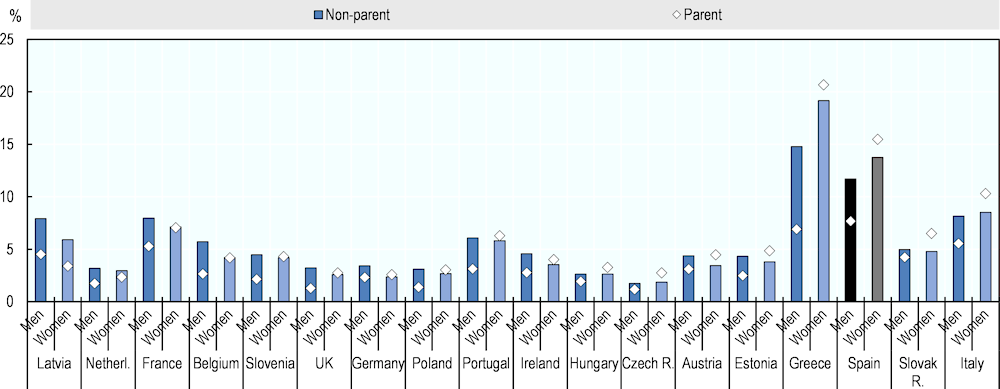

Participants in the Spanish labour market who are parents have a lower probability of being unemployed compared to non-parents when they are men, but a higher one when they are women. When excluding the youth population (who are less likely to be parents but more likely to be unemployed), there is a clear patterns across all the studied European OECD countries that fathers who live with their young children are less likely to be unemployed than the group of men who are either childless, do not live with their children or whose children are teenagers or older (Figure 1.10). In Spain, at 4 percentage points, the difference is quite elevated. For women, in contrast, there is no such uniform pattern: in Latvia and the Netherlands, mothers have a lower unemployment rate than the group of childless women and women who have older children or are not living with them. In six countries, the difference in the two group’s unemployment rates is below half a percentage point, while in ten countries, mothers have a higher unemployment rate. Spain is among the latter group, with the third-highest difference in the unemployment rate of mothers compared to women who do not parent young children they are living with.

Figure 1.10. Mothers in Spain have a higher unemployment rate than women who are not parents

Note: Countries are ordered by the difference in the unemployment rate between women who are mothers and those who are not. Parental status is proxied by living in a household where the youngest child in the household is aged 14 or under.and who have an own child living in the household. Parents who do not live in the same household as their children are hence mis-classified as non-parents; and for example grandparents under the age of 65 who live in multi-generational households with their child and grand-child would be mis-classified as a parent of a young child.

Source: OECD calculations based on the EU-LFS.

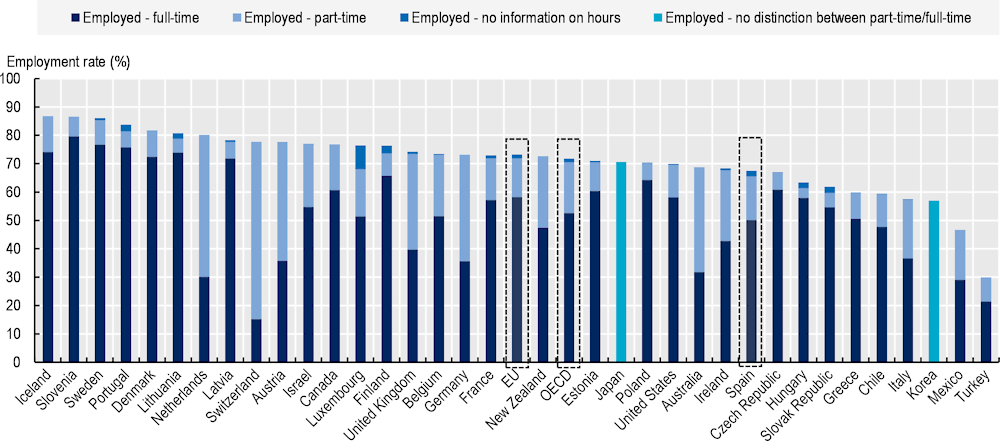

In 2019, about two‑thirds (67%) of mothers were employed in Spain. This share is lower than in many other EU and OECD countries, where 73% and 71% respectively of mothers were employed on average (Figure 1.11). Among working mothers, three‑quarters work full-time, whereas only one‑quarter works part-time. While maternal employment rates vary distinctively with the partnership status of mothers across the OECD, the employment rates of partnered and single mothers hardly differ in Spain.

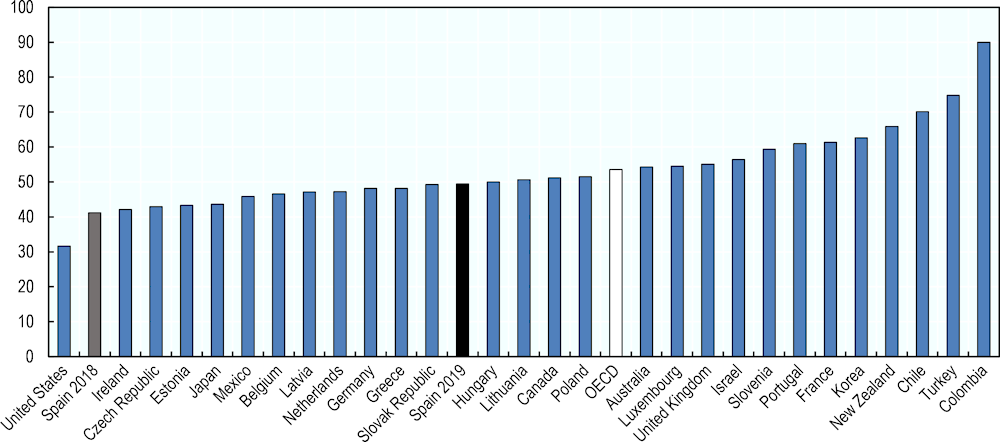

For many years, the minimum wage in Spain was amongst the lowest of the OECD. When measured as a ratio of the country’s median wage, the minimum wage barely reached 40% throughout the 2000s and 2010s. A significant increase in the minimum wage in 2019 brought the Spanish minimum to median wage ratio more in line with other OECD countries (Figure 1.12). In 2018, 1.3% of women and 0.5% of men who were working full-time earned less than the minimum interprofessional salary; while 43.1% of women and 35.6% of men earned less in between one to two times the minimum salary (INE, 2019[53]).

Figure 1.11. Only two‑thirds of mothers in Spain are employed

Note: Part-time employment is defined as usual weekly working hours of less than 30 hours per week in the main job, and full-time employment as usual weekly working hours of 30 or more per week in the main job. Exact definitions on part-time and full-time status as well as on the included population of mothers differ for some countries, as indicated in the original source.

Source: OECD Family Database, Chart LMF1.2.A, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

Figure 1.12. The increase in the minimum wage in 2019 brought Spain more in line with other OECD countries

Source: OECD Labour Force Survey data.

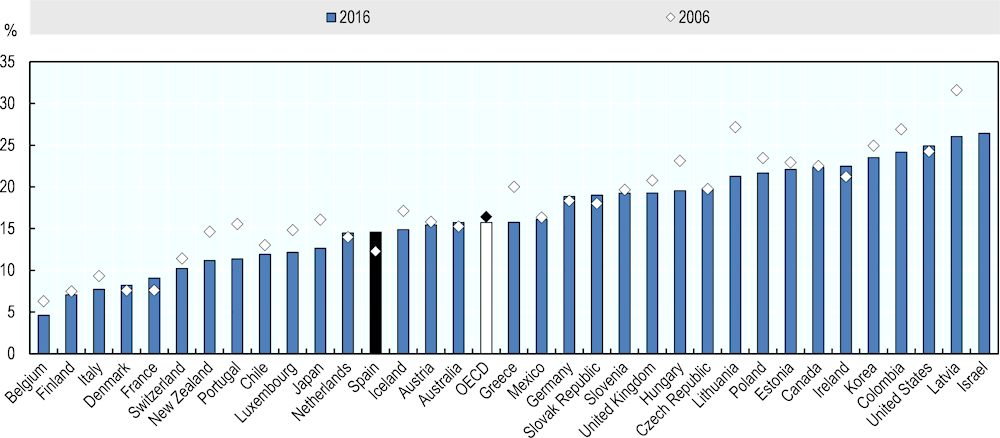

While the incidence of low pay is lower in Spain than in the average OECD country (Figure 1.13), it is one of the few OECD countries where the incidence rose between 2006 and 2016. In 2016, 14.6% of workers earned less than two‑third of median earnings, compared with 15.7% in the EU and OECD on average. The share in Spain rose by 2.3 percentage points over the timespan of a decade, whereas the average shares in the EU and OECD declined by respectively 1.3 and 0.7 percentage points. In Spain as well as on average across 22 European OECD countries, among full-time employees, fewer parents earn a low pay. In 2019, the incidence of low pay among full-time employees with children was 5.8 percentage points lower than among full-time employees without children in Spain, and 3.5 percentage points on average. The difference is smaller when the sample excludes employees under the age of 30, but still exists.5

Figure 1.13. Low pay is less frequent in Spain than in the average OECD country, but rose over the past decade

Note: The incidence of low pay refers to the share of workers earning less than two‑thirds of median earnings. Estimates of earnings used in the calculations refer to gross earnings of full-time wage and salary workers.

Source: OECD Earnings Distribution Database, www.oecd.org/employment/emp/employmentdatabase-earningsandwages.htm.

Rising housing costs

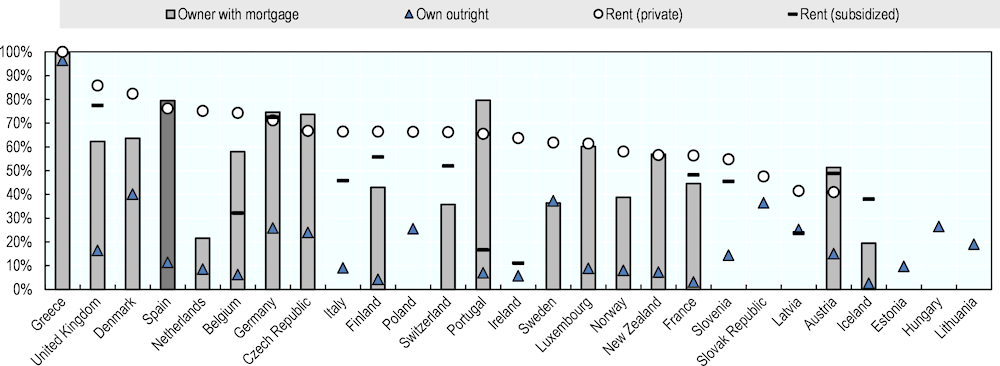

Housing affordability in Spain is only slightly worse than the OECD average, and only 3% of the population live in over-crowded conditions compared to 12% across the OECD. Nevertheless, in particular young people and tenants often have difficulties finding affordable and stable housing; and total housing costs are elevated for low-income households. Housing is a relevant, even determining, factor in family formation and plans over the life course, and has a large impact on well-being and family life. The increased price of housing and cost of rentals is one of the greatest obstacles young adults encounter to being able to live independently (Moreno, 2016[54]). According to 2019 data from the Spanish Youth Council, half of the population at ages 18 to 29 devotes over 30% of its income to housing, double the share in the total population. Furthermore, in 2017, 6.8% of people aged 18‑29 who were heads of household stated that they had paid their rent or a mortgage late, as opposed to 3.8% of the total population (Ayala et al., 2020[55]). Looking at households whose incomes fall into the lowest quintile, the share who pay more than 40% of disposable income on total housing costs (that is for example including taxes and utilities) is elevated for both tenants who rent from private owners and for owners who are still paying a mortgage (Figure 1.14). Low-income households do not only find it difficult to afford housing in urban but also in rural areas. In fact, while the share of low-income individuals with housing affordability problems rose more in urban than rural areas, the share among the latter also rose by around 20 percentage points between 1995 and 2007 (Dewilde, 2018[56]).

Figure 1.14. About four in five low-income tenants and mortgage‑paying households in Spain are overburdened by their housing costs

Note: Total housing costs include mortgage principal and interest repayment, rents, structural insurance, mandatory services and charges, regular maintenance and repair, taxes and utilities (including electricity, water, gas and heating). In the Netherlands and Norway no tenants at subsidised rate are subsumed into the private market rent category due to data limitations. No data on mortgage repayments available for Denmark. No distinction available between private or subsidised renters in New Zealand.

Source: OECD (2021[46]), “HC1.2 Housing costs over income”, Affordable Housing Database, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC1-2-Housing-costs-over-income.xlsx.

Spanish tax policy for a long time favoured home ownership. From 1995 onwards, the liberalisation of the rental market produced a dual housing market between those who could afford ownership and those who had to rely on the private rental market. Today, three‑quarters of Spanish people live in their own home they either own outright or have a mortgage on, still higher than the 68% OECD average (OECD, 2021[46]). The sharp increase in housing costs from the turn of the millennium onwards accelerated the transition to the dual earner family model. The housing policy deficits spilled over into family and social policy (Bosch and Trilla, 2019[57]; Módenes, 2019[58]). The 2008 crisis produced high figures of evictions and harassment of tenants. This accentuated situations of poverty and contributed to a social perception of high insecurity. Another crucial factor is the dominance of three to five year contracts in the private rental market that can be followed by substantial rent increases. This can produce a high perception of insecurity: once rooted in a place, tenant families face high costs to move if they cannot afford the increase in rents. This problem applies particularly to families with children, who choose and are assigned schools according to their neighbourhood.

Rural families face additional challenges

Demographic trends of depopulation and masculinisation and more difficult access to public and private infrastructure in rural areas can create challenges for families.

Rural spaces have been affected differently by the process of depopulation depending on the economic structure and labour opportunities for young generations. During the second half of the 20th century, and especially from 1960 to 1980, rural spaces experienced dramatic social, economic and demographic changes due to the mass migration towards urban areas. The rural population shrank by around 40%, reaching more than 50% in the inland regions of Spain (Pinilla and Sáez, 2017[59]). The trend did not stop in the new millennium, with three out of four towns in Spain having lost population between 2010 and 2020 (Secretaría general para el reto demográfico, 2019[60]). In 2020, 3 926 towns had a density under 12.5 inhabitants per km², the limit to be considered in demographic risk. As a comparison point, the OECD defines a rural community as having a population density below 150 inhabitants per km² (OECD, 2016[61]). These extremely low density areas represents 48% of Spanish territory (Secretaría general para el reto demográfico, 2019[60]).

Rural areas are not only becoming more sparsely populated but also older and more masculine. The ratio of inhabitants over the age of 65 to the inhabitants under the age of 15 is equal to nine in municipalities with less than 100 inhabitants, compared to around 1.3 in cities with more than 100 000 inhabitants. In towns with less than 1 000 inhabitants, 30% of the population are over the age of 65 and 15% of the age of 80 (Secretaría general para el reto demográfico, 2019[60]). The differences are bigger for women due to their greater life expectancy (Comisionado del Gobierno frente al Reto Demográfico, 2017[62]). Compared to the national average of 51.0%, the share of women is lower in rural areas: 49.4% in towns with under 5 000 inhabitants and even only 43.2% in towns under 100 inhabitants.

Low fertility rates and (higher female) out-migration lead to rural depopulation and ageing as well as the masculinisation. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the annual birth rate in Spanish rural territories has been around 6‑7 per 1 000 inhabitants, while the mortality rate has been around 11‑14 per 1 000, leading to negative natural growth (Pinilla and Sáez, 2017[59]). Studies show a greater predisposition among rural women than men to leave their hometowns. One reason is that they often face more difficulties in entering rural labour markets than men do. Cities off them better employment but also a more flexible and attractive lifestyle. Young men, who may have not completed school, in turn might find it difficult to move but also to find a partner in their local area. The arrival of immigrants has counterbalanced the exodus of young people born in rural areas in a small way: Foreign-born people represent 10% of the total rural population in Spain and 16% in the case of people between 20 and 39 years of age (Camarero, Sampedro and Reales, 2020[63]). The combination of rural emigration and low fertility rates have led to the emergence of the “support generation”, born between 1958 and 1977, who are in charge of taking care of their parents and children in the face of often weaker public services and infrastructures.

Along with fewer employment opportunities, the lack of access to private and public services are among the challenges for individuals in rural areas. The percentage of rural households having difficulties in accessing different types of private and public services (such as broadband internet and specialised medical care) is between 10‑20 percentage points higher than for metropolitan households (Camarero and Oliva, 2019[64]). This gap increases inequalities between urban-rural families and hinders the settlement of families in rural areas.

Schools, broadband internet and transportation infrastructure are among the key needs of rural families:

Schools play a key role among institutions in rural areas. They are often a prerequisite for keeping other social institutions, such as pharmacies, bakeries, bars or nursing home, in place because they make it possible for families with children to stay in or move to rural areas. Rural schools present more complexity in their organisation due the lack of resources and children, but they may also be spaces for implementing innovative learning practices, such as rural learning communities involving parental participation. Some Autonomous Regions have provided more resources to rural schools.

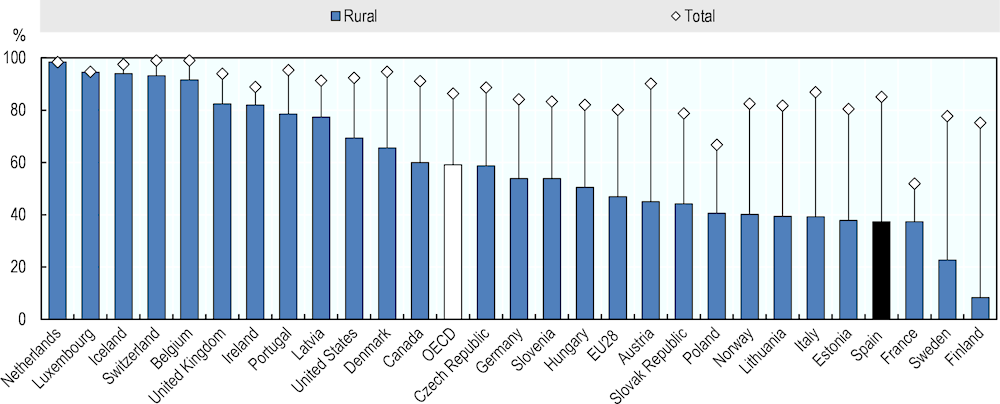

The provision of broadband internet can foster the diversification of rural economies towards new productive sectors linked to services and knowledge economy, and may facilitate teleworking. But in 2017, only 37.3% of rural households in Spain lived in an area where fixed broadband internet was available, compared to 85.0% of all Spanish households and an unweighted OECD average of 59.1% for rural households (Figure 1.15).

A good public transport infrastructure promotes the connection between rural towns and urban centres where educational, professional and social activities are located.

A lack of affordable housing in rural areas can make it difficult for new families to settle there or for young people to move out of their parental home. This phenomenon can occur in particular in regions where high income earners from urban areas buy secondary residences. At the same time, rural families may be more frequently faced with the necessity to find accommodation in urban areas for their young adult children who are pursuing higher educational degrees, because of a lack of higher education and training options in rural areas.

Figure 1.15. Fewer than one in four rural households in Spain could theoretically access high-speed internet in 2017

Note: For EU countries and Canada, rural areas are those with a population density less than 100 and 400 per square kilometre, respectively. For the United States, rural areas are those with a population density less than 1 000 per square kilometre. For EU countries, fixed broadband coverage is defined as NGA technologies (VDSL, FTTP, DOCSIS 3.0) capable of delivering at least 30 Mbps download speed. For the United States, coverage refers to fixed terrestrial broadband capable of delivering 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload services. Data for Canada and the United States refer to 2016. The OECD average refers to the unweighted average among the included countries.

Source: OECD (2019[65]), Measuring the Digital Transformation.

References

[21] Ajenjo-Cosp, M. and N. García-Saladrigas (2016), “Las parejas reconstituidas en España: un fenómeno emergente con perfiles heterogéneos / Stepfamily Couples in Spain: An Emerging Phenomenon with Heterogeneous Profiles”, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Vol. 155, https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.155.3.

[55] Ayala, L. et al. (2020), Analysis of social needs of youth, Observatorio Social de la Caixa, https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/en/informe-necesidades-sociales-juventud.

[3] Ayuso, L. (2019), “Nuevas imágenes del cambio familiar en España”, Revista Española de Sociología, Vol. 28/2, https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2018.72.

[7] Bernardi, F. (2005), “Public policies and low fertility: rationales for public intervention and a diagnosis for the Spanish case”, Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 15/2, https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928705049160.

[57] Bosch, J. and C. Trilla (2019), Housing system and welfare state. The Spanish case within the European context, Observatorio Social de la Caixa, https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/en/-/sistema-de-vivienda-y-estado-del-bienestar-el-caso-espanol-en-el-marco-europeo (accessed on 13 May 2021).

[11] Bueno, X. and J. García-Román (2021), “Rethinking Couples’ Fertility in Spain: Do Partners’ Relative Education, Employment, and Job Stability Matter?”, European Sociological Review, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcaa070.

[64] Camarero, L. and J. Oliva (2019), “Thinking in rural gap: mobility and social inequalities”, Palgrave Communications, Vol. 5/1, p. 95, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0306-x.

[63] Camarero, L., R. Sampedro and L. Reales (2020), La inmigración dinamiza la España rural, Observatorio Social de La Caixa, https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/es/-/la-inmigración-dinamiza-la-espana-rural (accessed on 17 April 2021).

[35] Castrillo, C. et al. (2020), “Becoming primary caregivers? Unemployed fathers caring alone in Spain”, Families, Relationships and Societies, https://doi.org/10.1332/204674320X15919852635855.

[20] Castro-Martín, T. and M. Seiz (2014), La transformación de las familias en España desde una perspectiva socio-demográfica, Fundación FOESSA, Madrid.

[24] CIS (2016), Estudio 3150, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, http://www.analisis.cis.es/cisdb.jsp (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[62] Comisionado del Gobierno frente al Reto Demográfico (2017), Despoblación, reto demográfico e igualdad, Ministerio de Política Territorial y Función Pública, https://www.mptfp.gob.es/dam/es/portal/reto_demografico/Documentos_interes/Despoblacion_Igualdad.pdf0.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

[43] Consejo de la Juventud de España and J. López Oller (2020), Observatorio de Emancipación. Balance Genderal - 1er Semestre 2020, Consejo de la Juventud, http://www.cje.org/descargas/cje7625.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[56] Dewilde, C. (2018), “Explaining the declined affordability of housing for low-income private renters across Western Europe”, Urban Studies, Vol. 55/12, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017729077.

[38] Duvander, A. and A. Jans (2009), “Consequences of Father’s Parental Leave Use: Evidence from Sweden”, Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, https://doi.org/10.23979/fypr.45044.

[44] Escobedo, A. et al. (2018), “Emancipació i familia: Una anàlisi dels arranjaments familiars i les trajectòries d’emancipació dels joves catalans incorporant la perspectiva de la satisfacció vital”, in Serracant, P. (ed.), Enquesta a la joventut de Catalunya 2017, http://treballiaferssocials.gencat.cat/web/.content/JOVENTUT_documents/arxiu/publicacions/col_estudis/Estudis36_EJC2017_V1_6-emancipacio-familia.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

[32] Escobedo, A., L. Navarro and L. Flaquer (2007), “Perspectivas de desarrollo y evaluación de las políticas de licencias parentales y por motivos familiares en España y en la Unión Europea”, Colección Estudios Sociales 3.

[42] Escobedo, A. et al. (2021), Changes in the work-life balance, family relations, wellbeing and happiness perceptions in Spanish households during the COVID-19 lockdown.

[8] Esteve, A. and R. Treviño (2019), “The main whys and wherefores of childlessness in Spain”, Perspectives Demografiques 15, https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/worpap/2019/204270/perdem_a2019m04n015iENG.pdf.

[25] European Commission (2019), Eurobarometer on Discrimination 2019: The social acceptance of LGBTI people in the EU, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/ebs_493_data_fact_lgbti_eu_en-1.pdf.

[26] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020), LGBTI Survey Data Explorer, https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2251_91_4_493_ENG (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[51] Eurostat (2021), At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold and household type - EU-SILC and ECHP surveys, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_li03&lang=en (accessed on 18 February 2021).

[12] Eurostat (2020), Household Composition Statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/1/1b/Households_composition_2019data_v0.xlsx (accessed on 15 February 2021).

[22] EVS/WVS (2021), European Value Study and World Value Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017-2021 Dataset.

[39] Eydal, G. and T. Rostgaard (eds.) (2014), Fatherhood in the Nordic welfare states, Bristol University Press, Bristol, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t894gw.

[15] Flaquer, L. (2015), “El avance hacia la custodia compartida o el retorno del padre tras una larga ausencia”, in España 2015 Situación social, Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Madrid.

[18] Flaquer, L. and D. Becerril (2020), “Consecuencias socioeconómicas de la ruptura de parejas”, in Fariña, F. and P. Ortuño (eds.), La gestión positiva de la ruptura de pareja con hijos, Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia.

[19] Flaquer, L. and D. Becerril (2020), “La ruptura de parejas en cifras: La realidad española”, in Fariña, F. and P. Ortuño (eds.), La gestion positiva de la ruptura de pareja con hijos, Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia.

[33] Flaquer, L. and A. Escobedo (2020), “Las licencias parentales y la política social a la paternidad en España”, in Flaquer, L., T. Cano and M. Barbeta-Viñas (eds.), La paternidad en España: La implicación paterna en el cuidado de los hijos, CSIS, Madrid.

[27] Flaquer, L. and A. Escobedo (2009), “The Metamorphosis of Informal Work in Spain: Family Solidarity, Female Immigration and Development of Social Rights”, in Pfau-Effinger, B., L. Flaquer and P. Jensen (eds.), Formal and Informal Work: the Hidden Work Regime in Europe, Routledge, New York.

[36] Flaquer, L. et al. (2019), “La implicación paterna en el cuidado de los hijos en España antes y durante la recesión económica”, Revista Española de Sociología, Vol. 28/2, https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2018.61.

[13] González, J. and M. Requena (2008), Tres décadas de cambio social en España, Alianza Editorial, https://doi.org/10.2307/40184745.

[9] Hoorens, S. et al. (2011), Low Fertility in Europe - Is there still reason to worry?, Rand Europe, Cambridge.

[28] INE (2021), Cifras de población, https://ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

[14] INE (2020), Estadística de Nulidades, Separaciones y Divorcios: Notas de prensa, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid, https://www.ine.es/prensa/ensd_2019.pdf.

[53] INE (2019), Encuesta Anual de Estructura Salarial, Instituto Nacional de Estadística, https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=28182&L=0 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

[37] INE (n.d.), Encuesta de Empleo de Tiempo, 2010, https://www.ine.es/prensa/eet_prensa.htm (accessed on 17 February 2021).

[23] ISSP (2012), International Social Survey Program, Family and Changing Gender Roles IV, http://w.issp.org/menu-top/home/ (accessed on 5 February 2021).

[34] Meil, G. (2011), “El uso de los permisos parentales por los hombres y su implicación en el cuidado de los niños en Europa”, Revista Latina de Sociología, Vol. 1, pp. 61-97.

[1] Meil, G. (2011), “Individualización y solidaridad familiar.”, Colección Estudios Sociales, No. 32, Fundación “la Caixa”, Barcelona.

[2] Meil, G. (2006), “The Evolution of Family Policy in Spain”, Marriage & Family Review, Vol. 39/3-4, https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v39n03_07.

[41] Meil, G., J. Rogero-García and P. Romero-Balsas (2017), “Why parents take unpaid Parental leave. Evidence from Spain”, in Cesnuiytè, V. (ed.), Family Continuity and Change, Palgrave Macmillan.

[52] Miho, A. and O. Thévenon (2020), “Treating all children equally?: Why policies should adapt to evolving family living arrangements”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 240, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/83307d97-en.

[30] MITRAMISS (2021), Statistics of the Permanent Observatory of the Immigration, https://extranjeros.inclusion.gob.es/es/estadisticas/ (accessed on 15 February 2021).

[58] Módenes, J. (2019), “The Unsustainable Rise of Residential Insecurity in Spain”, Perspectives Demogràfiques, https://doi.org/10.46710/ced.pd.eng.13.

[54] Moreno, A. (2016), “Economic crisis and the new housing transitions of young people in Spain”, International Journal of Housing Policy, Vol. 16/2, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2015.1130604.

[45] Moreno, A. (2012), “The Transition to Adulthood in Spain in a Comparative Perspective”, YOUNG, Vol. 20/1, https://doi.org/10.1177/110330881102000102.

[40] O’Brien, M. and K. Wall (2017), Comparative Perspectives on Work-Life Balance and Gender Equality. Fathers on Leave Alone, Springer.

[46] OECD (2021), Affordable Housing Database, http://www.oecd.org/housing/data/affordable-housing-database/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

[4] OECD (n.d.), Fertility rates (indicator), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/8272fb01-en.

[29] OECD (n.d.), Foreign-born population (indicator), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a368e1b-en.

[48] OECD (2020), “How’s Life in Spain?”, in How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0876cc2d-en.

[31] OECD (2020), International Migration Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ec98f531-en.

[47] OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

[65] OECD (2019), Measuring the Digital Transformation: A Roadmap for the Future, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311992-en.

[50] OECD (2018), A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264301085-en.

[61] OECD (2016), OECD Regional Outlook 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260245-en.

[6] OECD (n.d.), OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm.

[5] OECD/European Union (2018), Settling In 2018: Indicators of Immigrant Integration, OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union, Brussels, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307216-en.

[59] Pinilla, V. and L. Sáez (2017), La despoblación rural en España: Génesis de un problema y políticas innovadoras, Centro de Estuios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo de Áreas Rurales, http://www.reis.cis.es/REIS/jsp/REIS.jsp?opcion=articulo&ktitulo=2465&autor=JUAN+MANUEL+GARC%CDA+GONZ%C1LEZ (accessed on 17 January 2021).

[60] Secretaría general para el reto demográfico (2019), El reto demográfico y la despoblación en España en cifras, Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico, https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/presidente/actividades/Documents/2020/280220-despoblacion-en-cifras.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

[16] Solsona, M. and M. Ajenjo (2017), “Joint Custody: One More Step towards Gender Equality?”, Perspectives Demogràfiques, pp. 1-4, https://doi.org/10.46710/ced.pd.eng.8.

[17] Solsona, M. et al. (2020), La custodia compartida en los tribunals. ¿Pacto de pareja? ¿Equidad de género?, Icaria Antrazyt, Barcelona.

[10] Sosa Troya, M. and N. Mahtani (2019), “Why women in Spain are waiting longer to have a baby”, El País.

[49] Thévenon, O. et al. (2018), “Child poverty in the OECD: Trends, determinants and policies to tackle it”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 218, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c69de229-en.

Notes

← 1. Different factors can contribute to the seeming discrepancy between the number of children born to unmarried parents and the number of minors living with parents. First, ‘living with parents’ can include situations of reconstituted families where both adults are parents but only one of them is a parent of the child or teenager in question. Secondly, the statistic includes older teenagers who were born at a time when out-of-wedlock birth were still less frequent. Third, a number of parents may only get married after having had one or all of their children.

← 2. Own calculations with statistical data from the National Statistical Office (INE) and the General Council for Judicial Power (CGPJ) for 2018.

← 3. This wave of the international comparative HBSC survey included questions on shared residence from the child’s perspective, allowing an analysis of joint custody arrangements and impacts on subjective well-being. In later survey waves the core questionnaire did not include this specific question. Spain also does not participate in the Generations and Gender Survey that covers relevant questions.

← 4. In order to closer to the poverty definitions of a number of OECD member states, the OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD) defines the at risk of poverty threshold at 50% of the median income, compared to a 60% cut-off for the equivalent Eurostat indicator. According to Eurostat, 29.5% of children in Spain were at risk of poverty in 2018.

← 5. The calculation of the low-pay incidence for all employees as presented in Figure 1.15 relies on earnings and labour force surveys, including the European Union Structure of Earnings Survey; while the calculation for parents relies on household surveys, including the EU-SILC.