Population ageing is characterised by a rise in the share of the older people resulting from longer life expectancy (see indicator “Life expectancy at birth and survival rate to age 65” in Chapter 3) and declining fertility rates. This has been mainly due to better access to reproductive health care, primarily a wider use of contraceptives (see indicator “Family planning” in Chapter 4). Population ageing reflects the success of health and development policies over the last few decades.

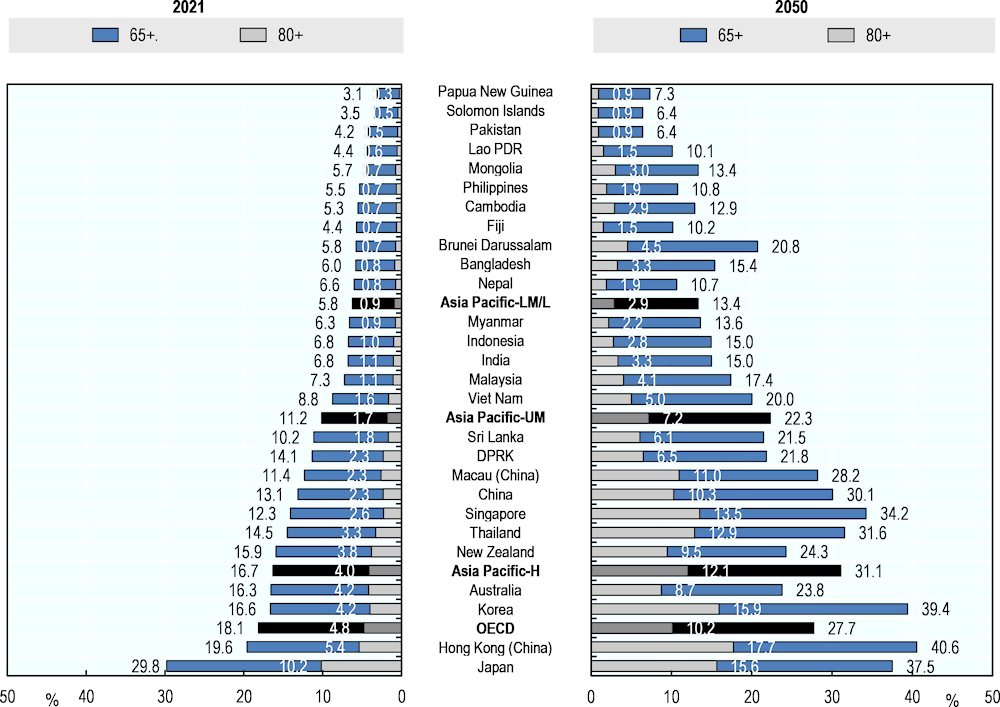

The share of the population aged 65 years and over is expected to double in lower-middle- and low-income Asia-Pacific countries and territories in the next decades to reach 13.4% in 2050. This is still lower than the high-income and upper-middle-income countries and territories average in 2050 of 31.1% and 22.3%, respectively (Figure 3.34). The share of older people will be particularly large in Korea and Hong Kong (China) where around 40% of the population will be aged 65 and over in 2050.

Globally, the speed of ageing in the region will be unprecedented. In 2050, seven Asia-Pacific countries and territories will be qualified as “ageing society” (as compared to 14 countries and territories in 2021), eight as “aged society” (four countries and territories in 2021) and 11 as “super-aged society” (only one country in 2020, that is Japan). Only Papua New Guinea is expected to show a share of population over age 65 lower that 7%, while 14 countries and territories fulfilled this criterion in 2020. The speed of ageing is particularly fast in Papua New Guinea and Mongolia, where the share of the population over 65 is expected to increase by more than five and four times, respectively, between 2021 and 2050. Many low- and middle-income countries and territories are faced with much shorter timeframes to prepare for the challenges posed by the ageing of their populations.

The growth in the share of the population aged 80 years and over will be even more dramatic (Figure 3.34). On average across lower-middle- and low-income Asia-Pacific countries and territories, the share of the population aged 80 years and over is expected to almost triple between 2021 and 2050, to reach 2.9% of the population. This proportion is expected to triple and quadruple in high-income and upper-middle-income countries and territories to reach 12.1% and 7.2% during the same period, respectively. The proportion of the population aged 80 years and over is expected to grow by six times in Singapore and Brunei Darussalam over the next decades.

The pressure of population ageing will depend on the health status of people as they become older, highlighting that the health and well-being of older people are strongly related to circumstances across their life course. As the number of older people increases, there is likely to be a greater demand for health care that meets the need of older people in the Asia-Pacific region in coming decades. All countries and territories in the region will urgently need to address drastic changes in demographic structures and subsequent changes in health care needs, especially the shifting disease burden to NDCs. Health promotion and disease prevention activities will increasingly need to address cognitive and functional decline, including frailty and falls. The health and well-being of older adults are determined by a complex interplay of factors that accumulate across a person’s lifetime including political, social, economic, and environmental conditions that are largely outside the health sector. Therefore, health systems will need to be reoriented to become more responsive to older people’s changing needs, including by investing in integrated and person-centred service delivery, supported by health financing arrangements and a health workforce with the right skills and ways of working, and integrated health and non-health services (e.g. welfare, social, education). The development of long-term care systems as seen in OECD countries may also be worth noting. Increasingly, there is a need to foster innovative home‑ and community-based long-term care pathways tailored to older people’s specific and diverse needs.

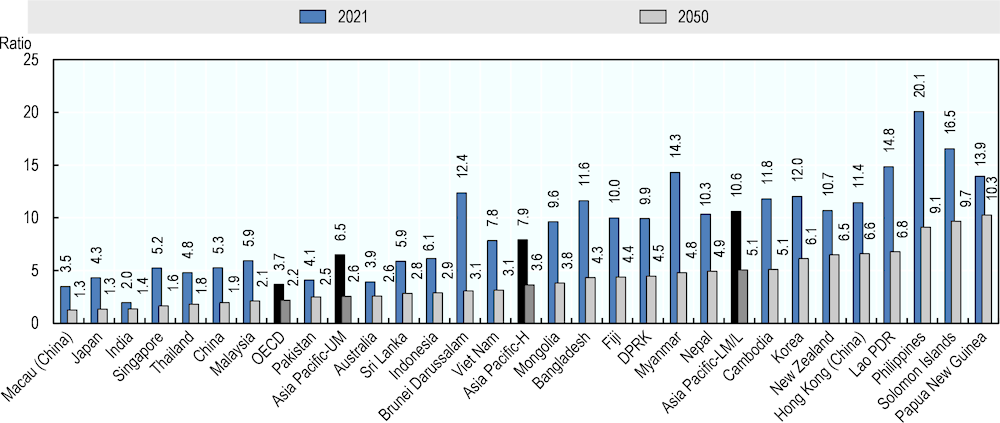

Over the next few decades, the increase in the population aged 65 years or more will outpace the increase in the economically active population aged 15‑64 across countries and territories in Asia-Pacific (Figure 3.35). In 2050, the ratio of people aged 15‑64 to people aged over 65 years will be two‑fifths of the 2021 value in upper-middle-income Asia-Pacific countries and territories (2.6 in 2050 vs 6.5 in 2021), whereas it will be slightly less than half the 2021 value in high (3.6 vs 7.9) and lower-middle- and low-income (5.1 vs 10.6) Asia-Pacific countries and territories. In Macau (China), Japan, India, Singapore, Thailand and China, there will be two or less persons aged 15‑64 for each person aged over 65 years in 2050. This underscores the importance of the society reform to encourage social participation of older people. Older adults contribute to society in a variety of ways including through paid and unpaid work, caregiver for family members, passing down knowledge and traditions to the younger generations.

These dramatic demographic changes will affect the financing of not only health systems but also social protection systems, and the economy. Moreover, older age often exacerbates pre‑existing inequities based on income, education, gender, and urban/rural residence, highlighting the importance of equity-focused policy making in future (OECD, 2017[1]). Population ageing does not only call for equity-focused, gender-responsive and human rights-based action within the health sector but also require collaboration across sectors to address the underlying determinants of health of older people, including housing, transport, and the built environment.