National development is largely dependent on healthy and well-nourished people, but many children are not always able to access sufficient, safe and nutritious food and a balanced diet that meets their needs for optimal growth and development for an active and healthy life (UNICEF, 2019[1]). Malnutrition amongst children in low-and middle-income countries and territories encompass both undernutrition and a growing problem with overweight and obesity. Many countries and territories are facing a double burden of malnutrition – characterised by the coexistence of undernutrition along with overweight, obesity or diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) – which poses a real and growing health challenge. A double burden of malnutrition exists at the population, household and individual levels in all countries. This includes overweight mothers and stunted children and children who are both stunted and overweight. For example, one in two overweight children are stunted in Bangladesh, and 6% of stunted children have overweight mothers in Myanmar (WHO, 2020[2]). In order to simultaneously and synergistically address these challenges, the United Nations declared the Decade of Action on Nutrition in 2016 until 2025 and proposed actions such as strengthening sustainable, resilient food systems for healthy diets, assuring safe and supportive environments for nutrition at all ages, promoting nutrition-related education, and strengthening nutrition governance and promoting accountability (WHO, 2017[3]). This will contribute to achieving target 2.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals: “By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age”.

Undernutrition is an important determinant of poor health amongst young children and is estimated to explain around 45% of all under 5 child deaths worldwide (Development Initiatives, 2018[4]). To reduce under age 5 mortality, countries and territories need to not only implement effective preventive and curative interventions for newborns, children, and their mothers during and after pregnancy (see indicator “Infant and child health” in Chapter 5) but also to promote optimal feeding practice (see indicator “Infant feeding” in Chapter 4).

Child undernutrition is also associated with poorer cognitive and educational outcomes in later childhood and adolescence and has important education and economic consequences at the individual, household, and community levels. Overweight in childhood is related to early cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and orthopaedic problems. It is also a major predictor of obesity in adulthood, which is a risk factor for the leading causes of poor health and early death. Hence, preventing overweight has direct benefits for children’s health and well-being, in childhood and continuing into adulthood (UNICEF, 2019[1]).

In 2012, the World Health Assembly endorsed a comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition, which specified a set of six Global Nutrition Targets by 2025 and they include targets in stunting, wasting and overweight (WHO, 2014[5]). In 2015, the UN SDG also set targets referring to stunting, wasting and overweight amongst children.

High levels of stunting in a country are associated with poor socio‑economic conditions and increased risk of frequent and early exposure to adverse conditions such as illness and/or inappropriate feeding practices. Wasting may also be the result of a chronic unfavourable condition, like unsafe water and poor or lacking sanitary facilities. Recurrent events of wasting can increase the risk of stunting, and stunting increases the risk of overweight and obesity later in life (UNICEF, 2019[1]).

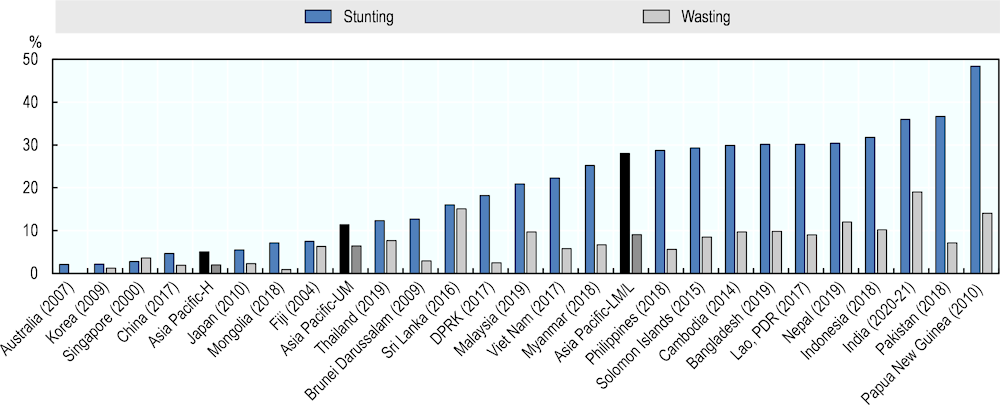

In Asia-Pacific, many countries and territories had a high prevalence of stunting amongst children under age 5. Stunting prevalence was high at around 50% in Papua New Guinea, and more than one in three children were stunted in Pakistan and India. On the other hand, stunting prevalence was below 5% in Australia, Korea, Singapore and China (Figure 4.6). In the past few years, Mongolia had made a substantial progress and became the first country in the Asia-Pacific region to have achieved the Global Nutrition Target to reduce by 40% the number of children under 5 years who are stunted. However, most South-East Asia countries are unlikely to achieve the global target or national targets set for stunting and wasting (WHO, 2020[2]).

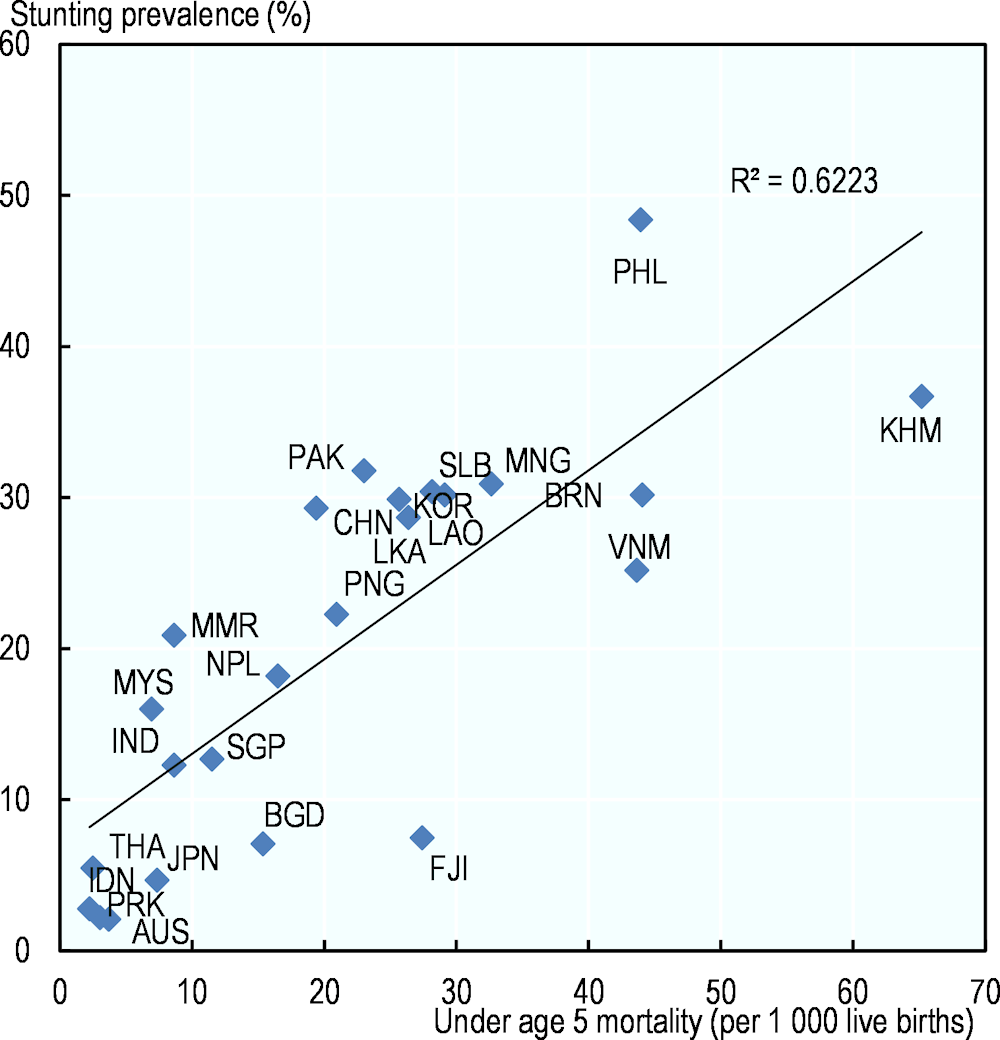

Countries and territories with high stunting prevalence had a high under age 5 mortality rate (Figure 4.7), also reflecting the fact that about 45% of under age 5 deaths were attributable to undernutrition (Development Initiatives, 2018[4]).

As to wasting, if there is no severe food shortage or an infectious disease (such as diarrhoea) that has caused children to lose weight, the prevalence is usually below 5% even in low-income countries and territories (https://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/about/introduction/en/index2.html), but it was higher than 10% in India, Sri Lanka, Papua New Guinea, Nepal, and Indonesia. So far, Australia, Mongolia, Korea, China, Japan, DPRK, Brunei Darussalam, and Singapore have attained the Global Nutrition Target of reducing and maintaining childhood wasting to less than 5% (Figure 4.6).

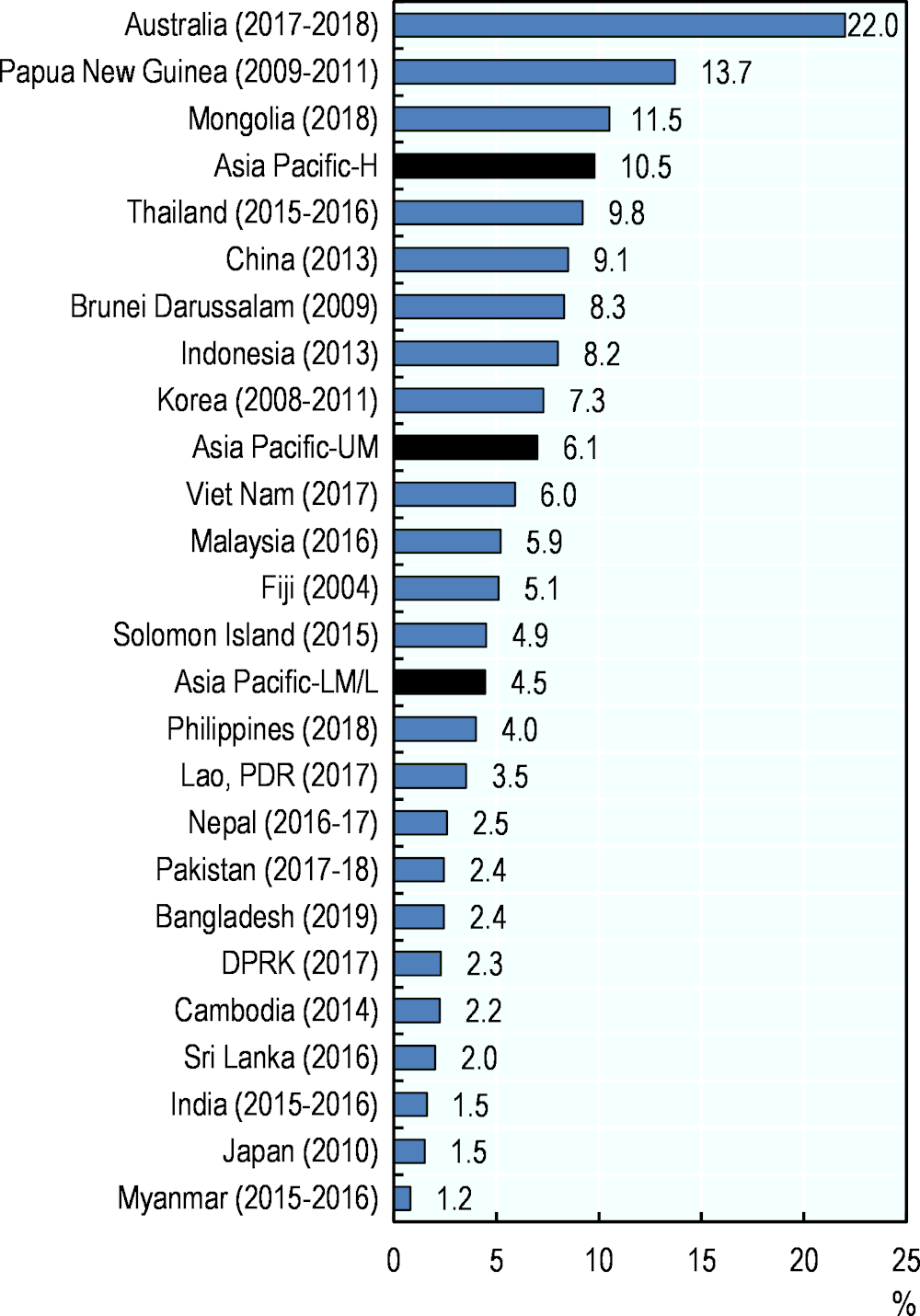

In 2018, almost 20 million overweight or obese children under age 5 lived in Asia (UNICEF, 2019[1]), and a high prevalence of overweight (5.2%) was reported for Pacific Island countries (UNICEF/WHO/WB, 2021[6]). However, the prevalence of childhood overweight varied across Asia-Pacific countries and territories. More than one child out of ten was overweight in Australia, Papua New Guinea and Mongolia, whereas less than 2% of children under age 5 were overweight in Myanmar, Japan, and India (Figure 4.8). Nepal, Pakistan and Thailand reduced under 5 overweight rates since 2012, so they meet the Global Nutrition Target 2025 of no increase in childhood overweight prevalence (WHO, 2020[7]). A low prevalence of overweight, however, did not always mean a proper nutrition intake amongst children. For instance, a study in Nepal showed that children under age 2 were getting a quarter of their energy intake from non-nutritive snacks and beverages such as biscuits or instant noodles (UNICEF, 2019[1]).