The UN Sustainable Development Goals set a target of ensuring universal access to reproductive health care services by 2030, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes. Providing family planning services is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions, contributing to significant reductions in maternal mortality and morbidity as well as overall socio‑economic development (UNFPA, 2019[1]).

Reproductive health requires having access to effective methods of contraception and appropriate health care through pregnancy and childbirth, to allow women and their partners to make decisions on fertility and provide parents with the best chance of having a healthy baby. Women who have access to contraception can protect themselves from unwanted pregnancy. Spacing births can also have positive benefits on both the reproductive health of the mother and the overall health and well-being of the child.

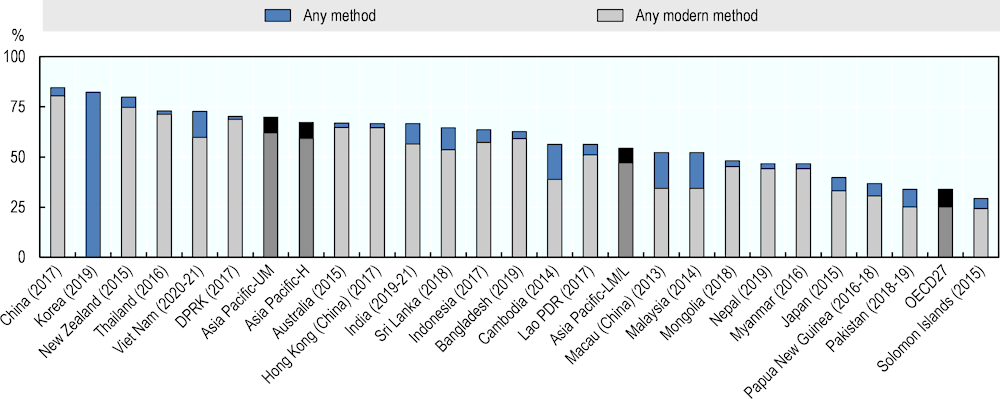

Modern contraceptive methods are more effective than traditional ones (WHO/Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2018[2]). The prevalence of modern methods use varies across countries and territories in Asia-Pacific. It was high on average across high-income and upper-middle-income countries and territories (59.2% and 62.0%, respectively). In a few of these countries and territories including China (80.5%), New Zealand (74.7%), Thailand (71.3%), and DPRK (68.8%), at least two‑thirds of married or in-union women of reproductive age reported using modern contraceptive methods (Figure 4.1).The average prevalence was low in lower-middle- and low-income countries and territories (47%). In the Solomon Islands, Pakistan, and Papua New Guinea, less than one out of three married or in-union women reported using any modern method.

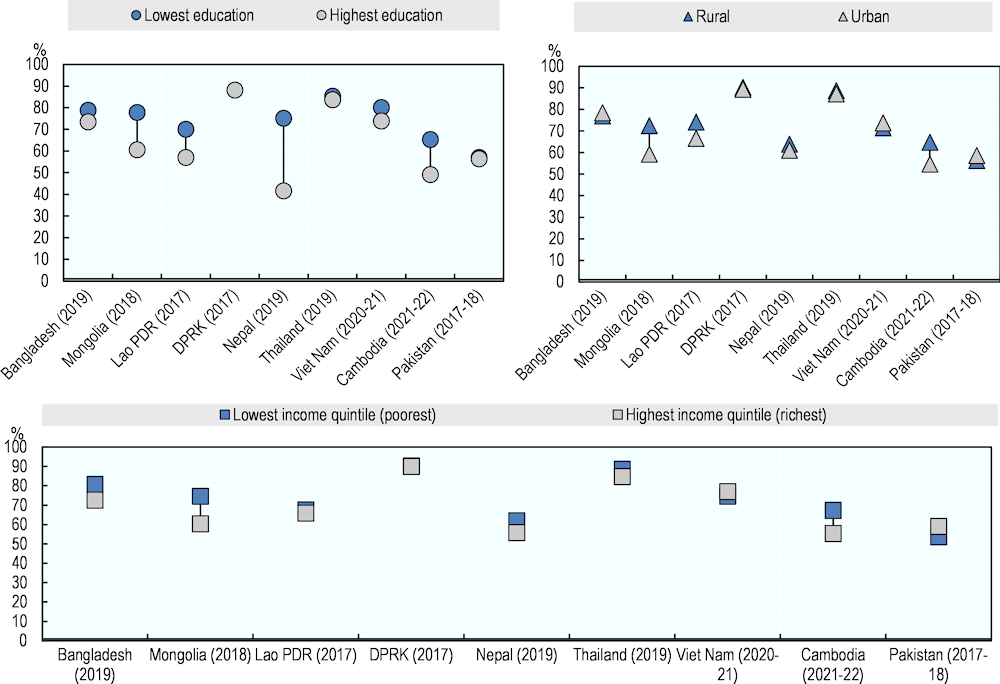

Based on population sizes, fertility rates, social welfare policies and regulations and service availability, differences in demand for family planning satisfied with modern methods exist in all reporting Asia-Pacific countries. In Nepal, demand satisfied is 34 percentage points higher amongst women with lowest education than amongst women with highest education, with a similar pattern observed in other reporting countries. (Figure 4.2). In Mongolia, demand satisfied is 13 percentage points higher amongst women living in rural areas than amongst those living in urban areas (72% versus 59%), while the proportion of women living in urban areas reporting demand for family planning satisfied is slightly higher than the proportion of women living in rural areas in Bangladesh (79% versus 77%), Pakistan (59% versus 56%) and Viet Nam (74% versus 71%). Based on income levels, the demand satisfied is 15 percentage points higher amongst women from households in the lowest income quintile than amongst women in the highest quintile in Mongolia (75% versus 60%), while the proportion of women in the highest income quintile reporting demand for family planning satisfied is higher than the proportion of women in the lowest income quintile in Pakistan (59% versus 54%) and Viet Nam (77% versus 75%) (Figure 4.2). Evidence suggests that demand for family planning not satisfied is high amongst adolescents and youth in Asia-Pacific countries and territories where the average age of marriage is low and gender inequality is high (UNESCAP, 2018[3]).