This chapter presents a range of indicators on living conditions; namely, immigrants’ income, housing, and health. It looks first at disposable household income (Indicator 4.1) and the risk of poverty (Indicators 4.2 and 4.3). It then considers housing indicators: tenure (Indicator 4.4), the incidence of overcrowding (Indicator 4.5), general housing conditions (Indicator 4.6), housing costs (Indicator 4.7), as well as the characteristics of the area where immigrants live (Indicator 4.8). Finally, it analyses self-reported health (Indicator 4.9), health risk factors (Indicator 4.10) and the lack of medical treatment (Indicator 4.11).

Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023

4. Living conditions of immigrants

Abstract

In Brief

Immigrants are on average much more likely to be poor than the native‑born, and income inequality is wider

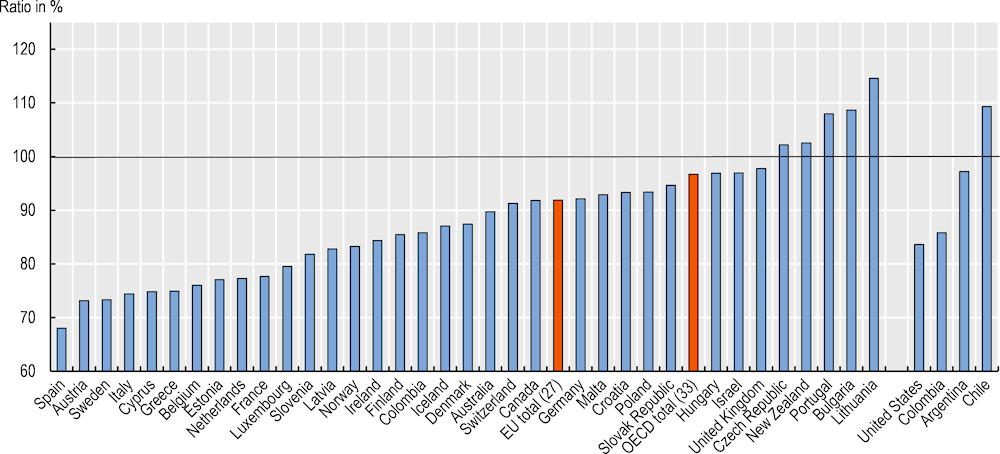

The median immigrant household income is over 90% that of the native‑born in the EU and OECD. Immigrant incomes are, however, less than 80% those of their native‑born peers in countries with large shares of non‑EU and low-educated migrants, such as in longstanding European destinations (bar Germany), Southern Europe (bar Portugal) and Sweden.

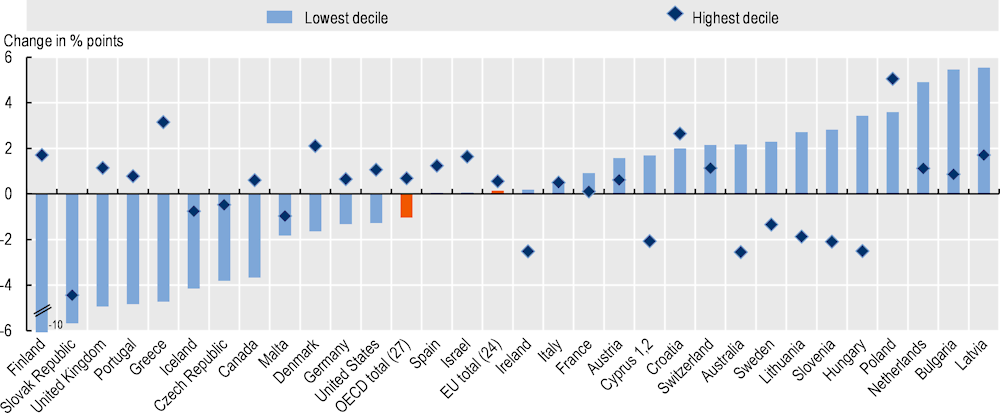

The distribution of immigrant income is highly unequal. Income inequality tends to be greater among the foreign- than the native‑born. Recent cohorts of immigrants are more likely than 10 years ago to be in the highest income decile in most countries, especially in Portugal, France and the United States.

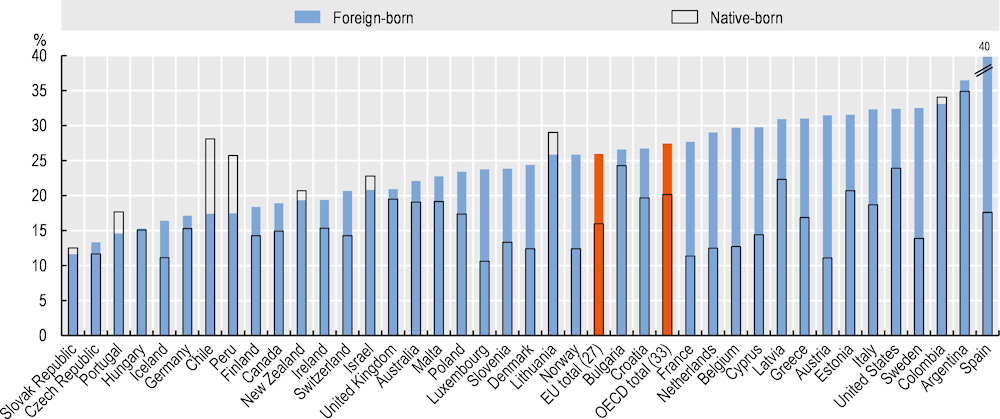

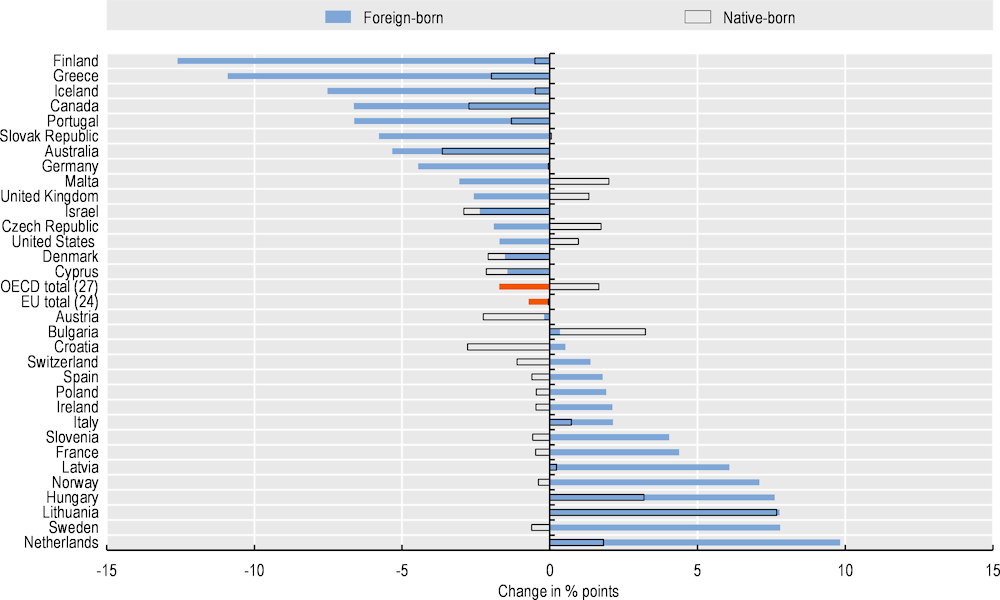

Immigrants are more likely to live below the relative poverty line of their country of residence than the native‑born in four out of five countries: notably in most European countries and the United States, though not in Latin America and Israel. Over the last decade, the share of immigrants living in relative poverty has fallen in slightly more than half of all countries.

Immigrants are much more likely to be at risk of poverty and social exclusion (AROPE) than the native‑born virtually everywhere in Europe, especially in Greece and Spain, where one in two immigrants is in this situation. The only exceptions are a few Central European countries with small immigrant populations and Portugal.

Fewer foreign- than native‑born own their homes and many live in bad housing conditions

In all countries (except Estonia and Latvia), native‑born home ownership rates exceed those of the foreign-born. Immigrants are only around half as likely as their native‑born peers to own their home in the EU. Gaps are widest in parts of Southern Europe, Latin America and Korea.

Although home ownership increases with duration of stay, it remains much lower in all countries (bar Estonia, Latvia and Hungary) than those of the native‑born even among settled migrants. In the EU, foreign-born from other EU countries are more likely to own their homes than their non‑EU counterparts (51% versus 37%).

Irrespective of tenure, migrants are more likely to live in overcrowded and substandard housing than the native‑born. More than one in six immigrants live in overcrowded accommodation in both the OECD and the EU – a rate that is 70% higher than that of the native‑born in the EU. What is more, 26% of immigrants live in substandard housing, against 20% of the native‑born.

In the EU, overcrowding increased among immigrants, but declined among native‑born. It has fallen among the foreign-born in the United States, the United Kingdom, Greece and Luxembourg.

In the EU, around one immigrant in five reports paying over 40% of their disposable income on rent, compared to roughly one in eight among the native‑born. Housing subsidies substantially narrow the gap between immigrants and the native‑born in Germany, France and the Netherlands.

Areas with housings in bad conditions are more likely to be rundown neighbourhoods. Therefore, immigrants are more likely to report problems with air quality, noise, litter or traffic in their neighbourhoods than the native‑born, at 19% against 15% EU‑wide. When accounting for differences in population density (immigrants are more likely to live in cities), gaps between the native‑ and foreign-born become narrower in most countries.

Health status of immigrants differs strongly by country of residence, but overall fewer report unmet medical needs than a decade ago

Immigrants report similar or better health than the native‑born in three‑fifths of countries, even after considering their lower age on average. Overall rates are highest in the settlement countries. Immigrants report lower health status than the native‑born in most longstanding European destinations and most Baltic countries.

Perceived health has improved over the last decade in most countries among both foreign- and native‑born.

Immigrants are less likely to be overweight than the native‑born in half of countries. The incidence of overweight among immigrants tends to increase with duration of stay in countries where the overall incidence of overweight is high, while falling in those where it is low.

Around 5% of both foreign- and native‑born report unmet medical needs in the EU and unmet hospital needs in Australia. Shares of unmet medical needs have declined among both the foreign- and the native‑born in most countries, though not among the foreign-born in Poland, Estonia, Belgium and the United Kingdom.

Immigrants are less likely to use healthcare and dental care services than their native‑born peers. They are more likely than the native‑born to report struggling to afford healthcare.

4.1. Household income

Indicator context

Income inequality can contribute to marginalise people and to erode social cohesion. Furthermore, low incomes may hamper immigrants’ ability to build a financially secure future for their family.

A household’s annual equivalised disposable income is total earnings per capita from labour and capital adjusted by the square root of household size. Median income divides all households into two halves: one receives less and the other more. The 10% of the population with the lowest income are in the first decile and the 10% with the highest income are in the tenth.

The median immigrant household income in the EU was almost EUR 18 000 in 2020, lower than in the OECD (around EUR 22 000). It is around 90% that of the native‑born in the EU overall, as well as in Australia and Canada, and less than 86% in the United States and Colombia. Immigrants’ incomes are lower than those of the native‑born in most countries – at least 23% less in longstanding destinations with many non‑EU migrants (bar Germany), Southern Europe (bar Portugal) and Sweden. EU‑wide, non‑EU migrant incomes are 84% those of their EU‑born peers. Even lower is the median income of low-educated immigrants – two‑thirds that of their highly educated peers in the EU and less than half in the United States. Although education improves immigrant household income in all countries, being highly educated does not close the gap with the native‑born. Highly educated immigrants in the EU show a 13% lower income than their native‑born peers (4% lower in the United States). By contrast, among the low-educated, again compared with their native‑born peers, immigrant income is only 3% lower in the EU, and even 4% higher in the United States.

While immigrants are overrepresented in the lowest income decile and underrepresented in the highest, their situation has improved in 1 in 4 countries over the last decade. The strongest improvements came in Finland, Greece, the United Kingdom and Portugal. In most countries, the cohorts of immigrants who arrived in the last 10 years were less likely to be in the lowest income decile and more likely to be in the highest in 2020 than recent cohorts in 2010. The trend was particularly strong in most Nordic countries, Portugal, France, Greece and the United States.

Income inequality (ratio between the tenth and the first decile) among the foreign-born tends to be wider than among their native‑born peers outside Europe (bar Israel and Australia). In the United States, the OECD country with the highest level of income inequality, income in the top decile outstrips the bottom by a factor of 7.1 among the foreign-born, and 6.5 among the native‑born. Income inequality is also greater among immigrants in European longstanding destinations, as well as in Spain and Denmark. However, income inequality is lower than that of the native‑born in around one‑quarter of countries, such as Estonia and Lithuania. Over the last decade, immigrant income inequality has declined in 2 EU countries in 5, albeit to a lesser degree than among the native‑born.

Main findings

Median immigrant household income is lower in most countries – around 90% that of the native‑born in the EU, Australia and Canada, and less than 86% in the United States and Colombia.

Recent cohorts of immigrants are more likely to be in the highest income decile than 10 years ago in most countries, especially in Portugal, France and the United States.

Income inequality among the foreign-born tends to be wider than among the native‑born.

Figure 4.1. Median income of the foreign-born as a percentage of native‑born

Figure 4.2. How the distribution of the lowest and highest income deciles have evolved for the foreign-born

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.2. Relative poverty

Indicator context

The relative poverty rate (or at-risk-of-poverty rate) is the proportion of individuals living below the country’s poverty threshold. The Eurostat definition of the poverty threshold used here is 60% of the median equivalised disposable income in each country.

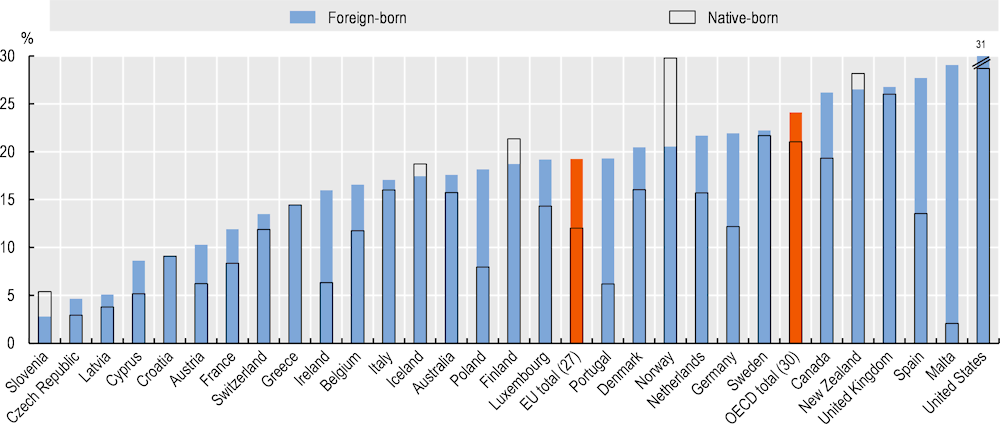

EU‑wide, 26% of the foreign- and 16% of the native‑born live in relative poverty. Differences are of a similar magnitude in the United States (8 percentage points), while moving in the opposite direction in New Zealand, Latin American OECD countries and Israel. In 4 out of 5 countries, the foreign-born are more likely than their native‑born peers to experience poverty. In Europe, differences between the foreign- and native‑born are wide in all longstanding destinations (save Germany), most Southern European countries, and those with considerable humanitarian intakes, e.g. Sweden.

Over the last decade, poverty rates have remained stable among the native‑born in the EU, while falling slightly among immigrants. Outside Europe, relative poverty has become less prevalent among both groups (bar the native‑born in the United States). In slightly more than half of countries, the share of immigrants living in relative poverty has declined, as it has among the native‑born. By contrast, increases among the foreign-born have been particularly stark in the Netherlands (by 10 points), as well as in Sweden and some Central and Eastern European countries. Virtually everywhere, changes in foreign-born relative poverty, whether positive or negative, were more pronounced than among their native‑born peers.

High levels of education – and, consequently, better chances of (stable) employment – are a buffer against relative poverty, albeit to a lesser degree among immigrants than the native‑born. Relative poverty is more common among the foreign-born in countries with predominantly low-educated, non‑EU migrant populations. As a result, one‑third of non‑EU migrants experience poverty, compared to less than a quarter of their EU‑born peers. The low-educated foreign-born are also more likely to be poor, at 36% EU-wide. However, gaps with the native‑born remain of a similar magnitude at all levels of education – around 10 points. This pattern is less true outside the EU, with differences between the highly educated foreign- and native‑born no more than 3 percentage points in the United States and the United Kingdom. What is more, at 16%, immigrants in employment are twice as likely as their native‑born counterparts to live below the relative poverty line in the EU. Similar gaps are found in the United States (24% vs 14%).

Main findings

Immigrants are more likely than the native‑born to live below the relative country’s poverty line across the EU (26% versus 16%). In longstanding European destinations, the share is often at least twice as high as among the native‑born. Immigrants are less likely to be in relative poverty outside Europe, however, except in the United States, Canada and Australia.

Between 2010 and 2020, relative poverty became less prevalent among migrants in slightly more than half of countries. However, fluctuations (either positive or negative) in the shares of those who do live in relative poverty were more pronounced than among their native‑born peers.

Immigrants in employment nevertheless remain twice as likely as their native‑born counterparts to live in relative poverty EU-wide (16% vs 8%). Similar gaps are found in the United States (24% vs 14%).

Figure 4.3. Relative poverty rates

Figure 4.4. How poverty rates have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.3. At risk of poverty or exclusion (AROPE)

Indicator context

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) lack the opportunity and resources to participate actively in the economic, political, social and cultural life of the host country.

This indicator, available for European countries only, indicates the share of people who are either at risk of poverty (Indicator 4.2), and/or severely materially and socially deprived, and/or living in a household with very low work intensity (less than 20% of the total combined work-time potential of all adults in the household during the previous year).

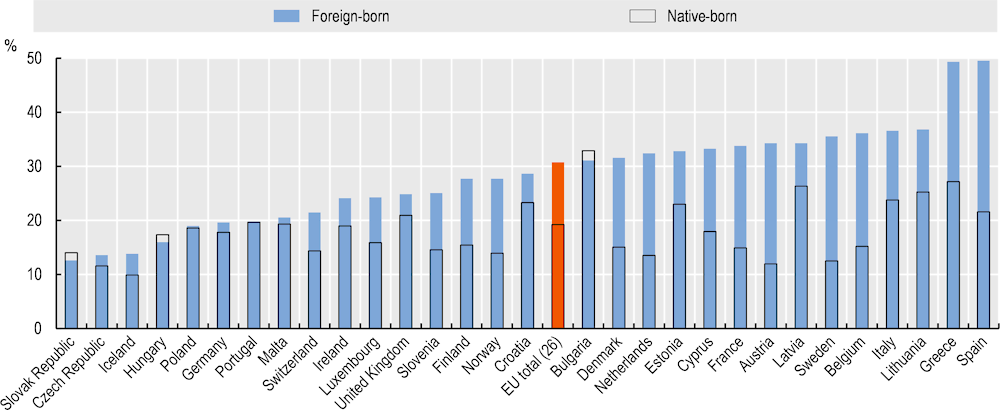

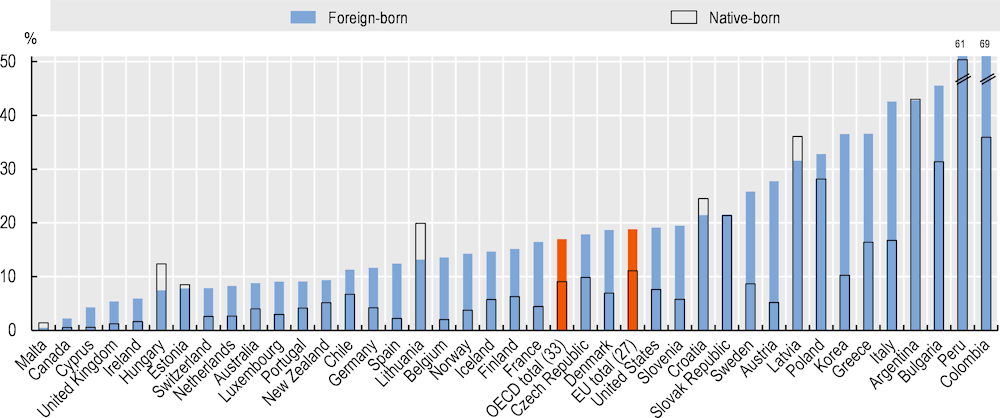

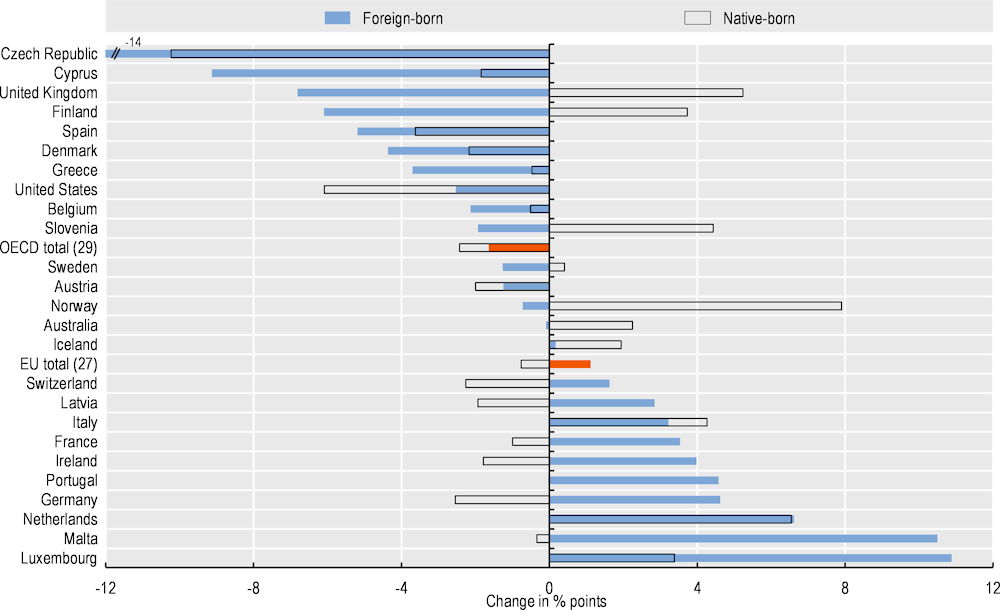

In the EU, around three in ten immigrants are at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE), against less than a fifth of the native‑born. They are more likely to be AROPE in virtually all European countries, especially in Greece and Spain, where one in two immigrants is in this situation. Immigrants are more at risk in over 12 percentage points in most of Southern Europe, some longstanding destinations and Nordic countries. By contrast, in Portugal, most Central and Eastern European countries, as well as Malta, where the foreign-born population has higher average levels of educational attainment, there are little or no differences. Non‑EU migrants are much more AROPE than their EU‑born peers in virtually all European countries. EU-wide, roughly two in five non‑EU migrants are affected, against only around one in four of the EU‑born.

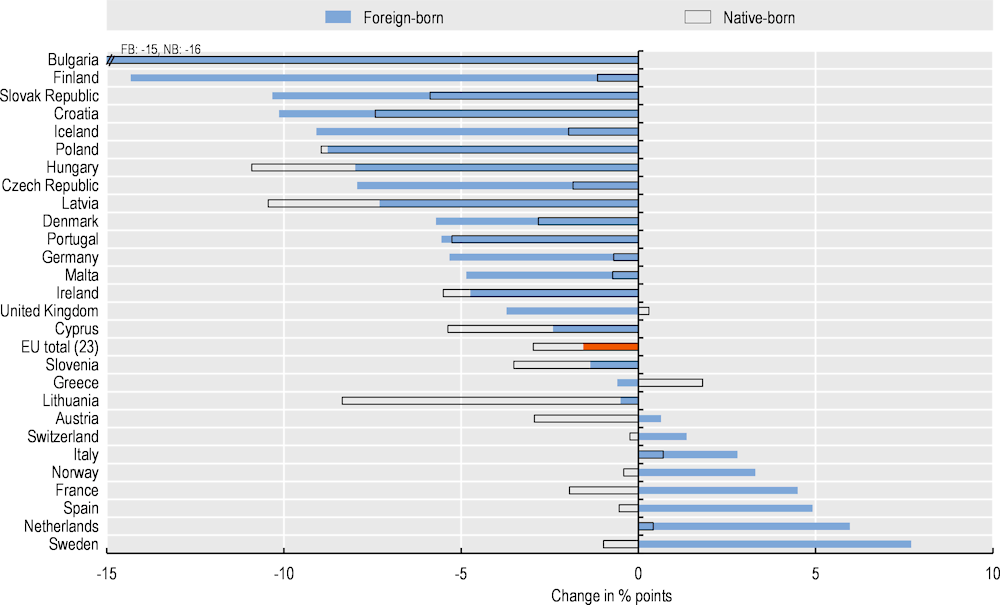

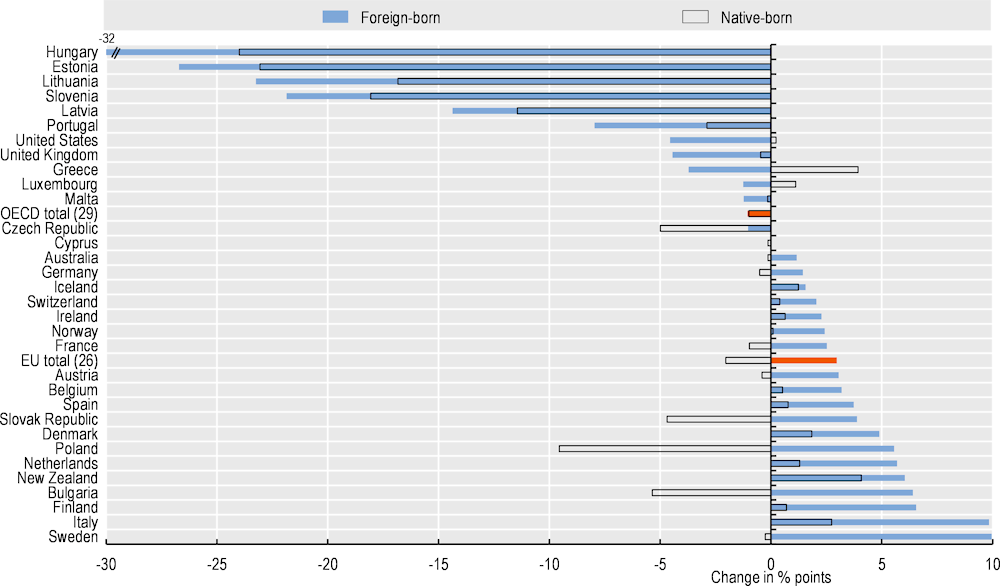

Over the last decade, the share of the foreign- and native‑born population at risk of poverty or social exclusion has fallen across the EU by 1 and 3 percentage points, respectively. It declined in two out of three countries among the foreign-born, and in four out of five among the native‑born. Except for some Central and Eastern European countries, where drops occurred, as well as Cyprus and Ireland, they have been steeper among the foreign-born. Consequently, gaps between the two groups have narrowed in several countries, particularly Finland and Iceland. By contrast, in some Southern European countries, as well as Sweden, Norway, France and the Netherlands, the share of immigrants who are AROPE has increased, while remaining unchanged among their native‑born peers.

Although the level of education decreases the risk of poverty or social exclusion considerably, the wide gaps between the foreign- and native‑born in exposure to the risk persist at high educational attainment. Indeed, in two‑thirds of countries, even highly educated immigrants are at least twice as likely to be AROPE as their native‑born peers: 18% vs 8% EU-wide. Another important determinant is duration of residence. Newcomers face specific barriers to the labour market and do not always enjoy full access to government transfers. As a result, they are at much greater risk of living in poor economic and social conditions, particularly in the Nordic countries and longstanding European destinations which are home to predominantly non‑EU migrants. In most of these countries, being a settled migrant nevertheless closes the gap with the native‑born by at least 40%.

Main findings

Immigrants are much more likely to be at risk of poverty and social exclusion (AROPE) than the native‑born virtually everywhere in Europe, especially in Greece and Spain, where one in two immigrants is in this situation. Exceptions are a few Central European countries and Portugal.

Over the last decade, the share of the migrant population that is AROPE has fallen in around two‑thirds of countries. Declines are usually steeper than among the native‑born population.

In two‑thirds of countries, even highly educated immigrants are at least twice as likely to be AROPE as their native‑born peers: 18% vs 8% EU-wide.

Figure 4.5. At risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE) rates

Figure 4.6. How AROPE rates have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.4. Housing tenure

Indicator context

Housing tenure shapes migrants’ settlement intentions and their sense of belonging. Home ownership, for example, secures housing and is associated with neighbourhood and civic engagement, better (mental) health, and higher net wealth.

This indicator relates to the share of homeowners among individuals aged 16 and over, to tenants who rent accommodation at the market rate, and to those who rent at reduced rates.

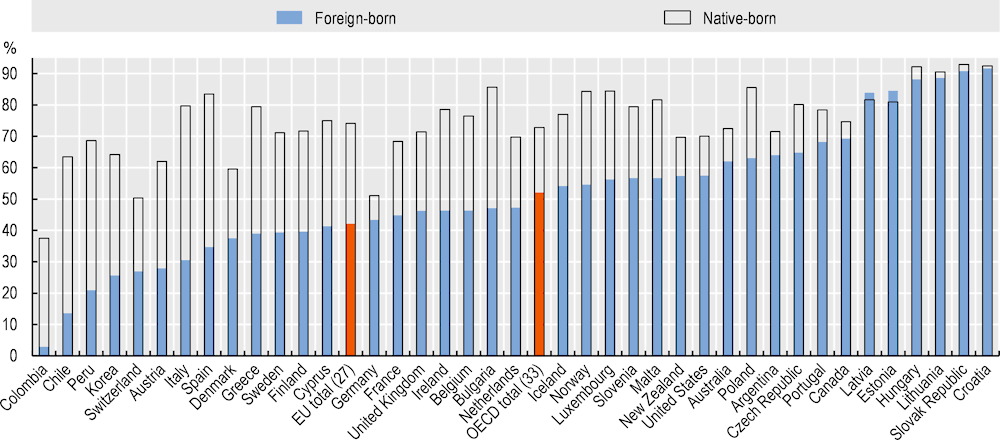

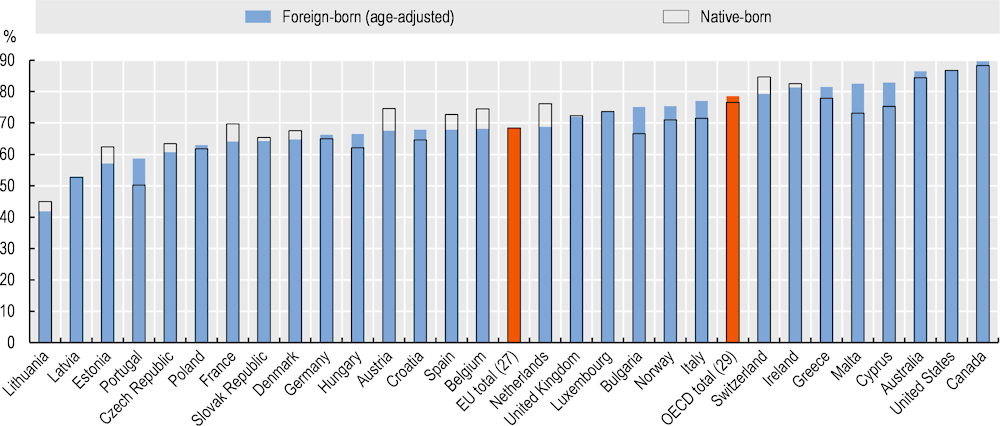

Home ownership among the native‑born population in the EU is nearly twice that of the foreign-born. In all countries (except Latvia and Estonia), native‑born home ownership rates exceed those of the foreign-born, with widest gaps (of at least 35 points) in parts of Southern Europe, Latin America and Korea. Unlike the native‑born, immigrants have no housing inheritance from their parents. Moreover, immigrants face obstacles to home ownership in the form of lower financial means, lack of knowledge of the host country´s housing market, and discrimination when purchasing property. Despite their more limited means, foreign-born renters across the EU are only slightly more likely than their native‑born peers (by 2 percentage points) to live in dwellings at a reduced rate. Indeed, in more than two‑thirds of countries, migrant tenants are less likely than their native‑born counterparts to rent accommodation below the market rate. A notable exception is France, where seven immigrant tenants in ten occupy housing at a reduced rate, against half of native‑born tenants.

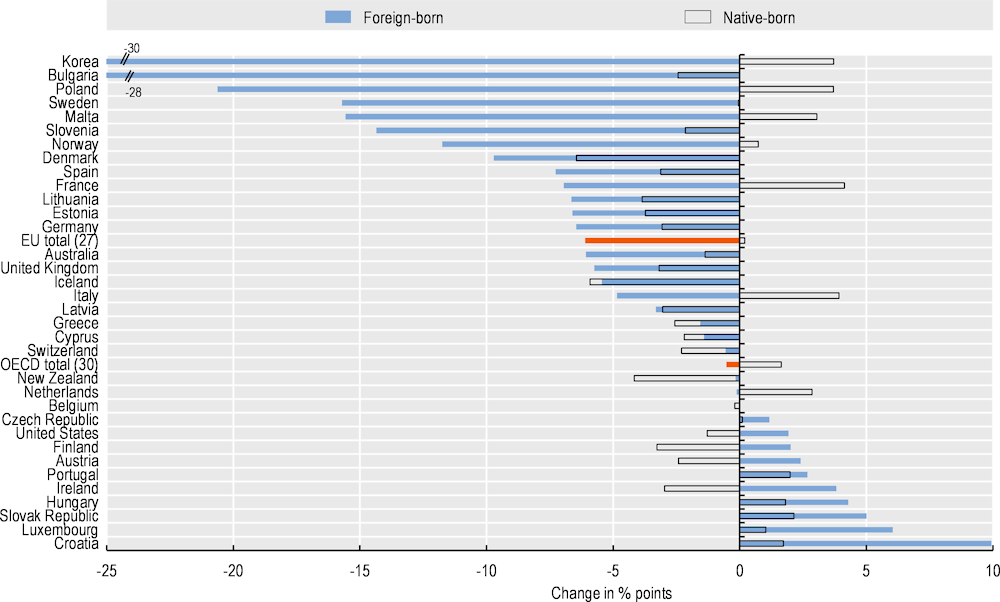

Over the last decade, ownership rates among the foreign-born have declined slightly in the OECD overall (by 1 percentage point), but more steeply in the EU (‑6 points). In around two‑thirds of countries, owning their home has become less likely for immigrants, especially in Korea and countries with ageing foreign-born populations –e.g. Bulgaria (home ownership down 28 points) and Poland (down 21 points). It has also fallen steeply in countries with large recent intakes of humanitarian migrants, such as the Nordic countries. At the same time, the proportion of foreign-born renting at reduced rates has risen in just over half of countries, while that of immigrants renting at the market rate increased in three‑quarters of countries.

Home ownership rates rise with duration of stay in the host country, which partly explains why they are lower in countries with many recent immigrants. However, even settled migrants (with more than ten years of residence) are still much more unlikely than the native‑born to own their homes in all countries (bar Estonia, Latvia and Hungary). Non-EU migrants are also less likely than EU‑born– 37% versus 51% to be homeowners.

Main findings

Home ownership is more common among the native‑born than the foreign-born in virtually all countries.

Although foreign-born home ownership increases with duration of stay, it remains much lower than those of the native‑born in all countries (except Estonia, Latvia and Hungary), even among settled immigrants.

Between 2010 and 2020, home ownership among the foreign-born fell in both the EU and OECD by 6 and 1 percentage points, respectively. As for the share of immigrant tenants renting at reduced rates, it rose, albeit more slowly than the share of tenants renting at the market rate.

Figure 4.7. Rates of home ownership

Figure 4.8. How home ownership rates have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.5. Overcrowded housing

Indicator context

Living in overcrowded accommodation can damage immigrants’ mental health and their ability to integrate in social and economic life. It also increases the risk of COVID‑19 infections, which is disproportionately high among immigrants.

A home is considered overcrowded if the number of rooms is less than the sum of 1 living room, plus 1 room for each single person or the couple responsible for the household, plus 1 room for every 2 additional adults, plus 1 room for every 2 children.

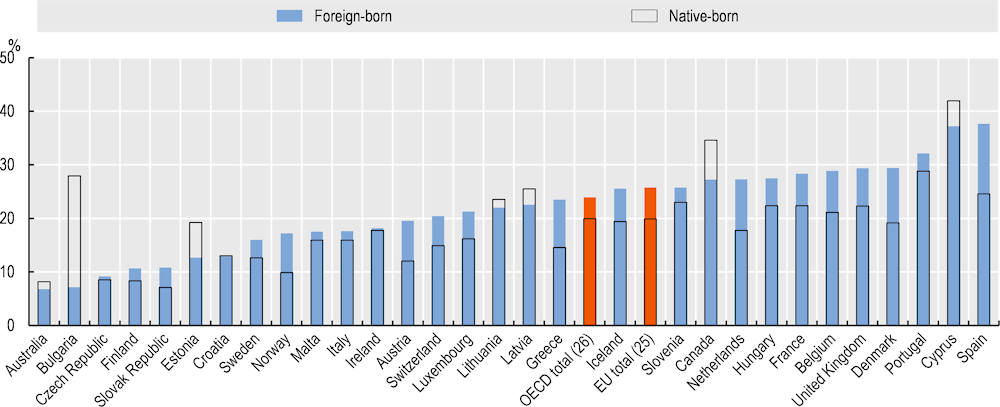

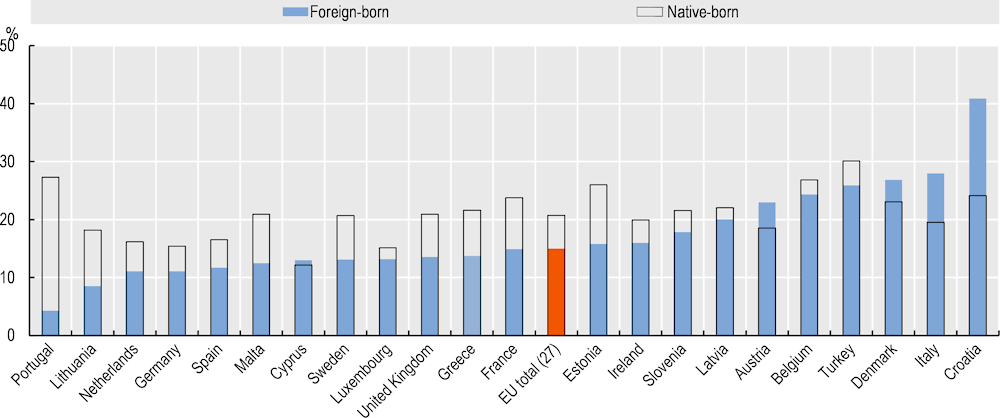

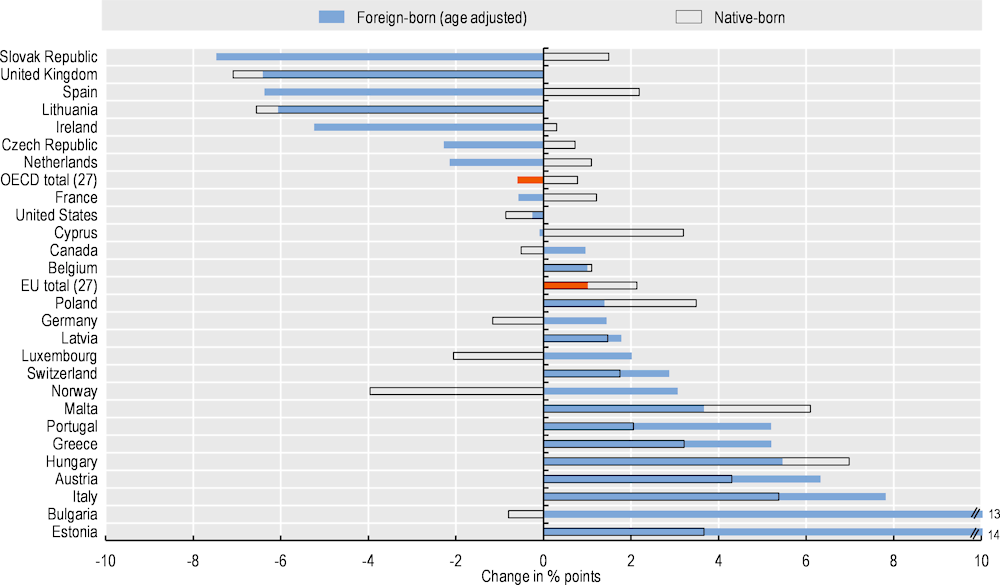

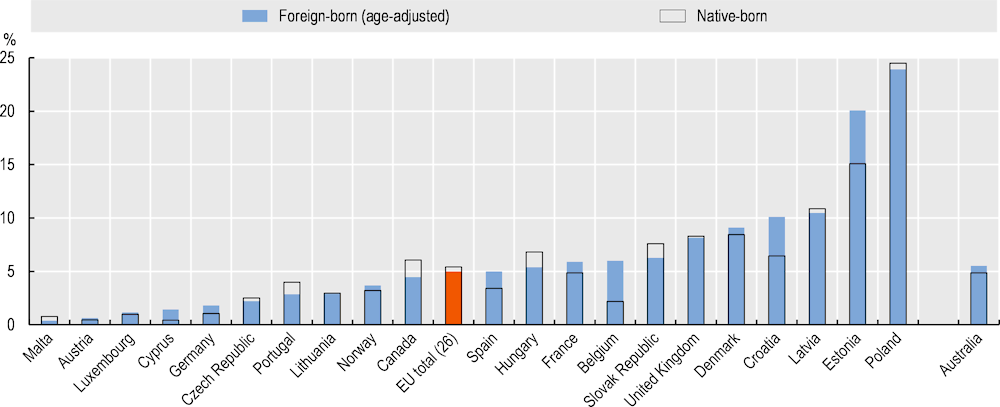

Over one‑sixth of immigrants live in overcrowded housing in both the OECD and the EU – a share that is 70% more than among the native‑born in the EU. Overcrowding is more widespread among the foreign- than the native‑born in virtually all countries. In two‑thirds of countries, overcrowding among immigrants is at least twice as likely as among the native‑born, and more than three times as likely in over one‑third of countries. The widest disparities are in Colombia, Korea, Southern European countries (particularly Italy and Greece), Nordic countries, and in European longstanding destinations (especially Austria).

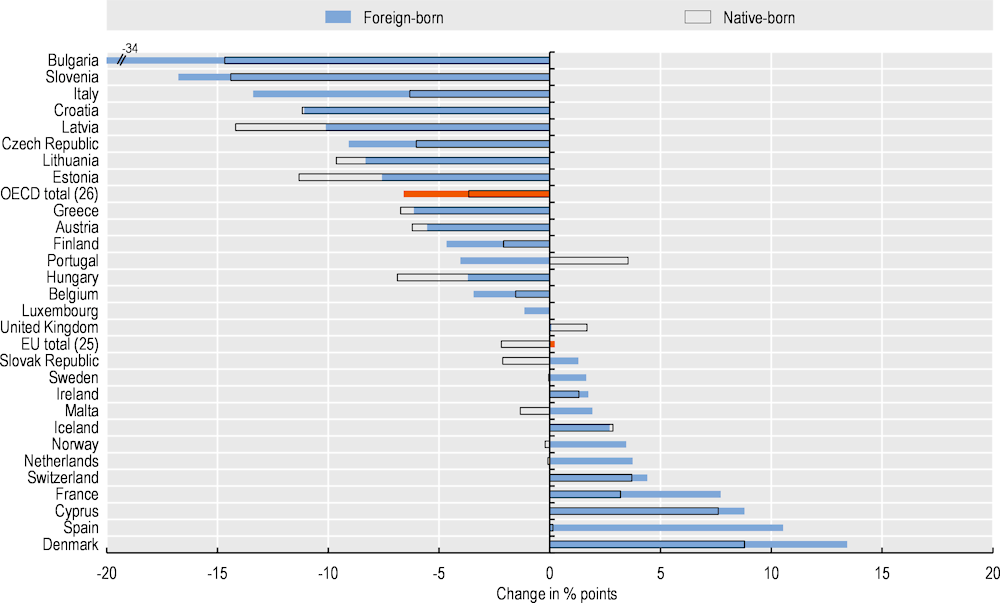

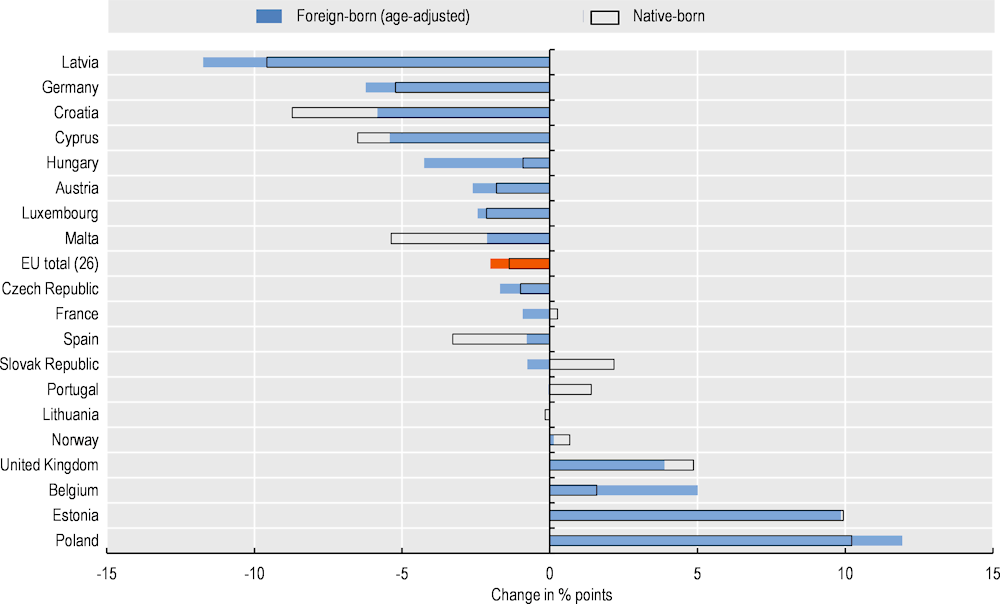

Over the last decade, the foreign-born overcrowding rate has risen by 3 percentage points in the EU, while falling 3 points among the native‑born, thereby enhancing disparities. Native‑born overcrowding has increased by more than 1 percentage point in just about one in five countries, while rising in three out of five among immigrants, particularly in Italy, some Nordic countries and some longstanding destinations with many non‑EU migrants. By contrast, overcrowding among immigrants and native‑born has declined in Portugal and most Central and Eastern European countries. It has dropped only for immigrants in the United States, the United Kingdom, Greece, Luxembourg and Malta.

Overcrowding gaps between the foreign- and native‑born are widest in countries where low incomes of immigrants restrict the choice of housing – i.e. in countries with the largest shares of non‑EU, low-educated and recent migrants, as well as foreign-born renters. In longstanding European destinations, Sweden and Southern Europe, overcrowding rates among the non‑EU born are on average twice those of EU-born. EU‑wide, recent migrants are also almost twice as likely as those who are settled to live in overcrowded housing, and 3 times as likely in Sweden, one of the countries with the highest share of the recently arrived foreign-born. Among both the foreign- and native‑born, overcrowding is also more common in rented than owned accommodation, with rates over three times higher in the EU and the United States among immigrant tenants. However, irrespective of tenure, immigrants are more likely to live in overcrowded housing than the native‑born in the vast majority of countries. Foreign-born owners in Finland, Malta and parts of Central and Eastern Europe are, however, less likely to live in overcrowded housing than their native‑born peers. This is also true among rent-paying foreign-born tenants in Luxembourg, Malta, Latvia and Croatia.

Main findings

Over one‑sixth of immigrants live in overcrowded housing in both the OECD and the EU – a share that is 70% higher than that of the native‑born in the EU. The widest disparities are in Colombia, Korea, Southern and Northern Europe, and longstanding European destinations.

Irrespective of tenure, immigrants are generally more likely to live in overcrowded housing.

In the last decade, overcrowding tended to rise among the foreign-born, but to fall among the native‑born in the EU. It has fallen only for immigrants in the United States, the United Kingdom, Greece, Luxembourg and Malta.

Figure 4.9. Overcrowding rates

Figure 4.10. How overcrowding rates have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.6. Housing conditions

Indicator context

Immigrants are at risk of living in poor housing, as they may lack knowledge of the housing market, have frequently limited financial means, and may face discrimination from proprietors.

This indicator shows the share of adults living in substandard accommodation. Accommodation is considered substandard if, for example, it is too dark, does not provide exclusive access to a bathroom, or if the roof leaks.

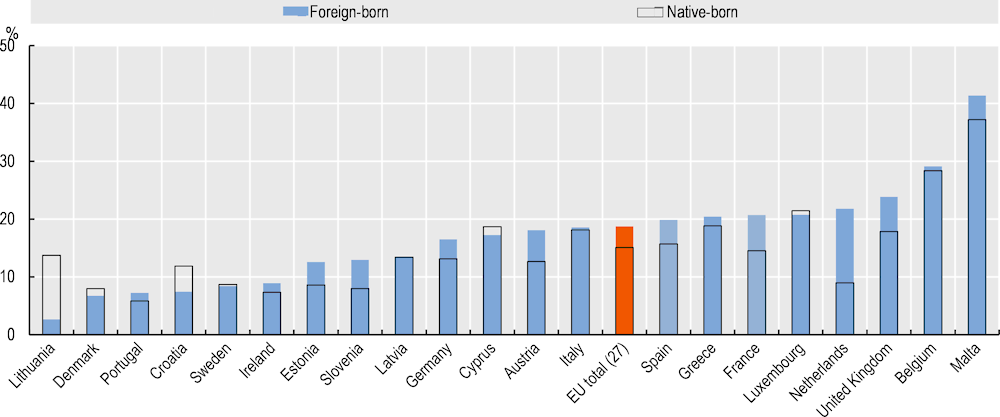

EU‑wide, 26% of immigrants and 20% of the native‑born live in substandard housing. In around three‑quarters of countries, the foreign-born are more likely to live in deprived accommodation, by as much as 13 percentage points in Spain and 10 points in Denmark and the Netherlands. By contrast, the native‑born are overrepresented among occupants of substandard housing in Cyprus, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Baltic countries, Canada and Australia. Closer scrutiny of housing problems reveals that immigrants in the EU are more likely than the native‑born to grapple with major construction defects (20% versus 15%) or lack of facilities to keep a comfortable temperature (10% versus 5%). EU‑wide, 6% of the foreign-born live in accommodation that is both overcrowded and substandard – twice as much as among the native‑born.

Over the last decade, the proportion of individuals living in substandard housing has dropped among the foreign-born in around half of countries, but in over two‑thirds among the native‑born. Shares of both immigrants and the native‑born in substandard accommodation declined in e.g. Italy, Greece and many Central and Eastern European countries with ageing populations. Immigrants’ housing conditions worsened, however, between 2010 and 2020, but remained stable among the native‑born in Spain, the Netherlands and Norway.

Housing conditions are generally better in owned homes than rented accommodation, particularly when it is rented at a reduced rate. As immigrants are underrepresented among homeowners in virtually all countries, they are more likely to live in substandard housing. Among tenants who pay rent (particularly those at a reduced rate), there is little difference EU-wide (less than 2 percentage points) in the standard of housing between foreign- and native‑born tenants. As for homeowners, differences are larger but remain relatively low (3 points). Nevertheless, immigrants remain slightly more likely to live in substandard housing, regardless of tenure. In Sweden, however, the native‑ and foreign-born face similar risks, again regardless of their tenure, while in Ireland and some Central and Eastern European countries, immigrants are less likely to live in substandard accommodation (in all types of tenure bar free‑of-charge accommodation).

Main findings

Immigrants are more likely to live in substandard housing than their native‑born peers (26% versus 20%), while 6% live in deprived and overcrowded accommodation (twice the share of the native‑born).

Housing conditions have improved among immigrants in half of countries: the same is true of the native‑born in over two‑thirds of countries.

Immigrants remain more likely than the native‑born to live in substandard housing, regardless of tenure. There is only little difference EU-wide in the standard of housing between foreign- and native‑born, when tenure is taken into account. There are no differences between the two groups in Sweden, regardless of tenure.

Figure 4.11. Substandard accommodation

Figure 4.12. How the shares of individuals living in substandard accommodation have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.7. Housing cost overburden rate

Indicator context

Immigrants are particularly vulnerable to high housing costs, as they are more concentrated in urban areas, struggle to access affordable accommodations and tend to earn lower incomes. Housing cost burdens hamper their ability to save, keeping them at an economic disadvantage.

The housing cost overburden rate is the percentage of households that spend over 40% of their disposable income on rent. It does not include housing subsidies, unless stated otherwise.

EU‑wide, around one‑fifth of immigrant renters are overburdened by housing costs, against one‑eighth of the native‑born. While housing cost overburden rates are higher overall in non-European countries (save Australia), immigrants are nevertheless more likely to be under financial strain to pay their rent, although to a lesser extent. Only in Slovenia, New Zealand and most Nordic countries is that strain lower among the foreign-born. Housing subsidies narrow the gap in the housing cost overburden rate between immigrants and the native‑born by 2 percentage points in the EU, while closing it in New Zealand. Although those subsidies halve the gap in some countries with large immigrant populations, such as Germany, France and the Netherlands, they make no substantial difference in most countries. In the United Kingdom, Denmark and Ireland, foreign-born actually receive less housing subsidies despite their higher poverty.

Although housing cost overburden rates have fallen over the last decade in more than half of countries among both foreign- and native‑born, the situation has improved more for immigrants in three out of five countries. In Slovenia, the United Kingdom and Nordic countries with large recent intakes of humanitarian migrants (except Denmark), rates have dropped among immigrants but risen among the native‑born, so closing the gap observed in 2010. The opposite was the case in e.g. Germany, Ireland and Malta. In Switzerland, Latvia, Luxembourg, France and the United States, immigrants are now more likely to be overburdened by rent than the native‑born, unlike in 2010.

The greater access of the low-educated to housing at reduced rate in most countries does not compensate for lower incomes: they are more overburdened by housing costs than their highly educated peers. However, differences between the foreign- and native‑born are wider among the highly educated than their low-educated peers in two‑thirds of countries, with notable exceptions such as France, Germany and Ireland. In Greece and all Nordic countries (except Denmark), low-educated immigrants are actually less likely than their native‑born peers to spend 40% of their income on rent, while those with tertiary education are more likely. The Nordic countries (except Denmark) are also among the few where recent migrants are less overburdened by housing costs than settled migrants despite being poorer, which points to those countries’ affordable housing capacity for newcomers. Even with lower incomes, non‑EU migrants have a lower housing cost overburden rate than their EU peers in the EU (17% vs 21%).

Main findings

One‑fifth of immigrants are overburdened by housing costs in the EU, against one‑eighth of the native‑born. Gaps tend to be narrower outside Europe. Housing subsidies substantially reduce the gap between immigrants and the native‑born in Germany, France and the Netherlands.

In Slovenia, the United Kingdom and Nordic countries (except Denmark), gaps in housing cost overburden rates between the foreign- and native‑born have closed over the last decade.

In the Nordic countries (except Denmark), low-educated and recent migrants are less overburdened by housing costs than their native‑born and settled peers, unlike other countries.

Figure 4.13. Housing cost overburden rate

Figure 4.14. How housing cost overburden rates have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.8. Characteristics of the neighbourhood

Indicator context

Neighbourhood characteristics can affect integration outcomes, such as economic opportunities, living conditions and civic engagement, as well as the quality of schooling.

This indicator, which is only available for European countries, shows the shares of adults, aged 18 and over, who report struggling to access non-recreational amenities (banking facilities, grocery shops or supermarkets) and experience least one major problem in their neighbourhoods (noise, air quality, litter or heavy traffic).

EU‑wide, 21% of the native‑ and 15% of the foreign-born report to struggle to access non-recreational amenities in the neighbourhoods where they live. Overall, in two‑thirds of EU countries, the native‑born population reports poorer access to amenities than immigrants – by as much as 23 percentage points in Portugal and 10 points in Estonia. By contrast, the foreign-born in Croatia, Italy, Austria, Denmark and Cyprus report greater access difficulties, by 17 points in Croatia and 9 in Italy. Among immigrants, the EU‑born report slightly more often that accessing non-recreational amenities is harder than their non‑EU-born peers. When it comes to recreational amenities (green spaces, cinemas, theatres, cultural centres) and public transport, the overall picture in the EU is similar ‑ foreign-born access is 8 points less difficult.

Larger proportions of foreign- than native‑born live in rundown neighbourhoods. In the EU, the share of immigrants who report at least one major vexation (noise, air quality, litter or heavy traffic) exceeds that of the native‑born (19% versus 15%). The pattern is especially true of longstanding immigration countries, such as the Netherlands, where the gap is 13 percentage points, and France and the United Kingdom, both with 6 points. In roughly a quarter of countries, by contrast, the native‑born are more likely to experience major concerns in their neighbourhood, especially when it comes to heavy traffic. Among immigrants, those born outside the EU are as likely as their EU‑born peers to report at least one important issue.

In the EU, immigrants are more likely to live in rundown parts of large urban areas (see Indicator 2.4). While these areas generally enjoy better access to amenities than rural areas (where the native‑born are overrepresented), city-dwellers are also more likely to have to contend with serious matters like noise, air quality, litter or traffic. Factoring an area´s population density reduces differences in the native‑ and foreign-born experience in most countries – both in neighbourhood issues and access to non-recreational amenities. Indeed, with regard to access to amenities, adjusting for both the neighbourhood’s population density and working hours further reduces differences. What is more, as the native‑born are more likely to be in employment in many countries, they may struggle to access non-recreational amenities if their standard working hours coincide with the amenities’ opening times.

Main findings

In most European countries, immigrants are more likely to report concerns associated with rundown neighbourhoods, while finding it easier than the native‑born to access amenities.

Factoring in different population densities and working hours (access to non-recreational amenities being more difficult outside standard working hours) narrows differences between native‑ and foreign-born experiences of the neighbourhood in most countries – both in neighbourhood issues and access to non-recreational amenities.

Figure 4.15. Difficulties in accessing non-recreational amenities in the neighbourhood

Figure 4.16. Major problems with air quality, noise, litter or traffic in the neighbourhood

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

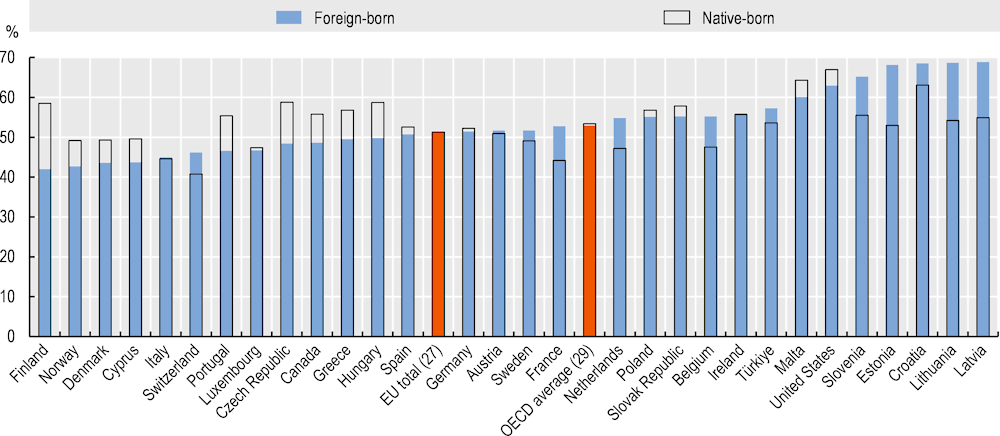

4.9. Reported health status

Indicator context

Self-reported health status is measured by the share of individuals who rate their health as good or better. As health status is strongly age‑dependent, the share of immigrants who report good health is adjusted to estimate outcomes as if the immigrant age structures were the same as those of the native‑born.

In 2020, higher shares of the native‑ than foreign-born claimed good health in half of countries, especially Switzerland, Estonia, and longstanding destinations with many non‑EU migrants (except in Germany and the United Kingdom). In Austria and Belgium, most of the gap is driven by non‑EU migrants’ self-reported poorer health. In the other half of countries, by contrast, immigrants reported health that was similar to or better than that of the native‑born, for instance, in Norway, the United States, and countries where the immigration population has been shaped by labour migrants, as in Australia, Canada and Southern European countries (except Spain).

Shares of the foreign- and native‑born reporting good health rose in most countries over the last decade, though not in the United Kingdom or the United States. Estonia and some Southern European countries saw much sharper increases in reports of good health among the foreign-than the native‑born. By contrast, immigrants reported declining and the native‑born rising health in around one‑quarter of countries.

Factors, such as age (which this indicator controls for), levels of education, and behaviours in countries of destination and origin (see Indicator 4.10), affect health status and perceptions. Recent migrants also feel healthier in all countries (except Belgium, Switzerland and Greece). This may be due to the fact that they are positively selected compared to the overall population in their countries of origin (the so-called “healthy migrant effect”, which fades over time). Perceived health status also has a strong gender component, albeit to a lesser extent outside Europe. Women (particularly foreign-born) are less likely to report good health than men in virtually all countries. That gender dimension is particularly strong among immigrants in Norway, Portugal and most countries of Central and Eastern Europe. In Ireland and the United Kingdom, where there is no difference in self-reported health status between male and female native‑born, immigrant women are at least 5 percentage points less likely to report good health than their male peers. Low-educated people (whatever their country of birth) are also much less likely to report good health than their highly educated peers. However, in most countries where immigrants are less likely to report good health than the native‑born, this situation persists across educational levels, although the gap is much smaller among the tertiary-educated in Switzerland, the Netherlands and France and reversed in Lithuania.

Main findings

Immigrants are as or more likely than native‑born to report good health in half of countries. They are less likely in most longstanding European destinations and most Baltic countries.

Perceived health increased over the last decade in most countries among the foreign- and native‑born.

Lower shares of women than men report good health in all countries. Gender gaps are larger among the foreign-born.

Figure 4.17. Self-reported good health status

Figure 4.18. How shares of foreign- and native‑born in self-reported good health have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

4.10. Risk factors for health

Indicator context

Smoking and obesity are two major individual risk factors for chronic diseases.

People with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 and over are considered overweight. BMI is a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in metres. The share of overweight immigrants might be underestimated, since studies show that BMI cut-offs for overweight are lower for most ethnic groups. The share of tobacco smokers includes people who report smoking daily. Alcohol consumption is not covered as heavy episodic drinking is not available by country of birth.

Shares of overweight people vary widely by country and between immigrants and the native‑born. Overweight prevalence is significantly lower among immigrants than the native‑born in around half of countries. Examples are the Nordic countries (except Sweden), as well as Malta and the United States. In the other half of countries, by contrast, immigrants are more likely to be overweight than their native‑born peers, especially in the Baltic countries, Slovenia and France. In Italy, Ireland or Germany, no strong differences emerged between the two groups.

The likelihood of being overweight depends on daily diet, which is related to attitudes and culture in countries of origin. However, since it also depends on diet in countries of residence, incidence of overweight usually increases with duration of stay in countries where prevalence is high, while falling in those where it is low. In virtually all countries, the low-educated are more frequently overweight than the highly educated, among the native‑ and foreign-born alike. In the EU, greater proportions of the low-educated native‑ than foreign-born are overweight, although controlling for the younger age structure among the foreign-born closes the gap. In the United States, by contrast, low-educated immigrants are more likely to be overweight than their native‑born peers. And when it comes to gender, men are more overweight than women, regardless of their place of birth. In almost all European countries, the gender gap is particularly wide among EU‑born.

Other behaviours are important health-risk factors. One example is smoking tobacco on a daily basis, more widespread among immigrants than the native‑born in most countries. EU‑born are more likely to smoke daily than the native‑born in over three‑quarters of countries. The widest gaps between foreign- and native‑born are in Austria, Slovenia, Cyprus and Malta. The smoking attitudes of immigrants have a strong gender bias – much more so than the native‑born. In fact, greater shares of foreign- than native‑born men smoke daily in two‑thirds of countries, while the opposite is true among women in most countries. In the Netherlands, for instance, immigrant men are almost twice as likely as native‑born men to smoke daily, while immigrant women are slightly less likely than their native‑born peers.

Main findings

Overweight prevalence is significantly lower among immigrants than the native‑born in around half of countries.

Incidence of overweight among immigrants usually increases with duration of stay in countries where the incidence is also high, while falling in those where it is low.

Gender differences in tobacco consumptions are large among immigrants. Immigrant men are more likely to smoke than native‑born men in two‑thirds of countries, while the opposite is true among women in most countries.

Figure 4.19. Overweight

Figure 4.20. Daily tobacco smokers

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

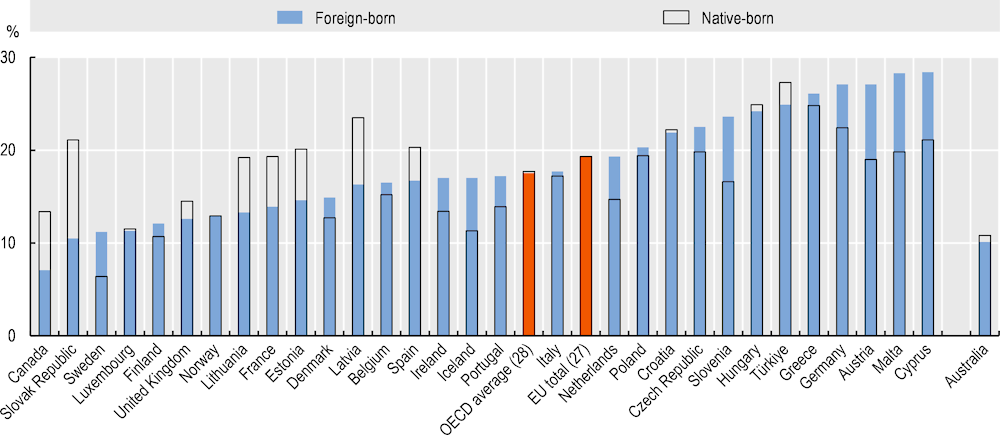

4.11. Access to healthcare and unmet healthcare needs

Indicator context

Immigrants may face linguistic, financial, administrative and cultural barriers to accessing healthcare services and may subsequently encounter unmet healthcare needs.

The indicator for unmet healthcare needs shows the (age‑adjusted) share of individuals who report that, over the previous 12 months, they have not received medical or dental healthcare despite being in need. The indicators for access to healthcare measure: (i) the share of individuals who find affording healthcare rather or very difficult and (ii) the share of households not having used any healthcare or dental care services in the previous 12 months.

In 2020, the share of immigrants reporting unmet medical needs EU‑wide was similar to that of the native‑born (around 5%). The same was true of Australia, where there were no significant differences in unmet hospital needs between the two groups. Indeed, differences were narrow (less than 1.5 percentage points) in most countries. However, the foreign-born were significantly more likely to report unmet medical needs in Belgium and Croatia (by around 4 percentage points), and in Estonia (by 5 points). The native‑born were slightly more likely in Canada. As for the EU, reports of needing but not receiving medical care were slightly more frequent among immigrants born outside the EU and recent migrants arrived over the last ten years than among the native‑born. What is more, reports of unmet dental needs were more common among the foreign-born (11%) than the native‑born (8%) – and even more common among recent arrivals (15%), the non-EU born (14%) and low-educated migrants (13%).

Between 2010 and 2020, the (age‑adjusted) shares of the foreign- and native‑born who reported unmet medical needs fell slightly in the EU. While the situation improved among both groups in most countries (particularly Latvia, Croatia and Germany), unmet medical needs nevertheless increased sharply among both native‑ and foreign-born in Poland (by 10 and 12 percentage points, respectively) and Estonia (10 points both). They also grew among immigrants in Belgium by 5 percentage points.

Generally, immigrant households (where all responsible persons of household are foreign-born) are less likely than their native‑born peers to use healthcare services virtually everywhere (77% versus 83% EU‑wide). They also pay fewer visits to the dentist or orthodontist (44% of foreign- versus 46% of native‑born households). Immigrants generally face more barriers to healthcare in the form of language proficiency, health literacy, financial constraints and possibly also legal access. Accordingly, at 36% versus 30% EU-wide, immigrants struggle more to afford healthcare services than the native‑born in all EU countries, except for Cyprus. Indeed, immigrants EU‑wide are more likely than their native‑born peers to report difficulties in affording emergency healthcare (26% versus 24%), mental health services (39% versus 35%), and dental care (43% versus 37%).

Main findings

Shares of immigrants and native‑born who report unmet medical needs are similar at around 5% in the EU and Australia (unmet hospital needs). They are slightly lower among immigrants in Canada.

Between 2010 and 2020, reported unmet medical needs fell among both foreign- and native‑born in the majority of countries.

Virtually everywhere, immigrants struggle more to afford healthcare, and are less likely to use healthcare and dental care services than their native‑born peers.

Figure 4.21. Unmet medical needs

Figure 4.22. How shares of individuals reporting unmet medical needs have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.