Elderly migrants are a growing group in most countries. Yet, as they reach the final stage of their lives, little is known about their integration challenges and outcomes. Those challenges are difficult to identify, as elderly migrants, reflecting long-standing migration flows, are often very different from other migrant cohorts. In most longstanding destinations, the aged immigrant population has been shaped by arrivals of low-educated “guest workers” and subsequent family migration. This chapter presents a first-time overview of select indicators for this group before the beginning of the COVID‑19 pandemic. It first describes the size and the age composition of the elderly population (Indicator 6.1). Then it looks at their living conditions, namely poverty (Indicator 6.2), housing conditions (6.3) and perceived health (6.4). The last indicator investigates their access to professional homecare (Indicator 6.5).

Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023

6. Integration of the elderly immigrant population

Abstract

In Brief

Despite migrants being younger on average than the native‑born in most countries, the elderly migrants are a growing group of concern

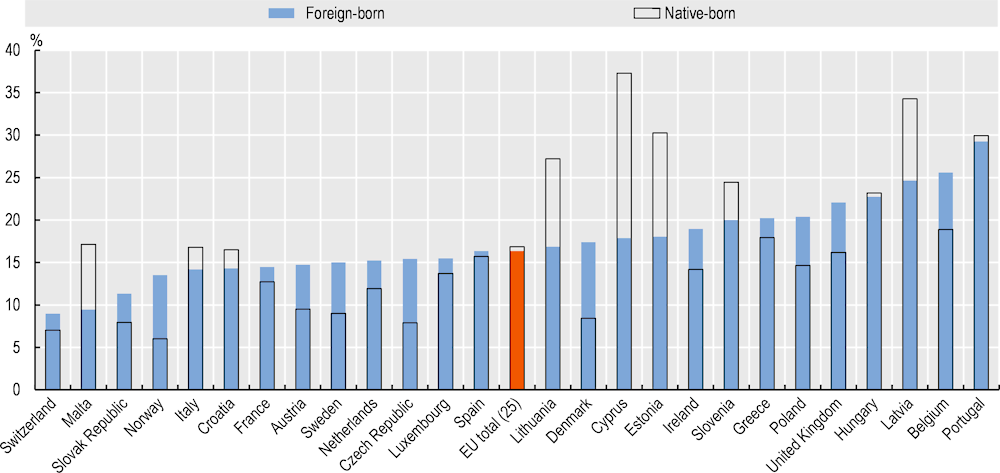

In both, the EU and the OECD, about 15% of the foreign-born population is over 65 years of age, a smaller share than among the native‑born populations in most countries. In about a third of countries, however, the foreign-born are more likely to be over 65 than the native‑born.

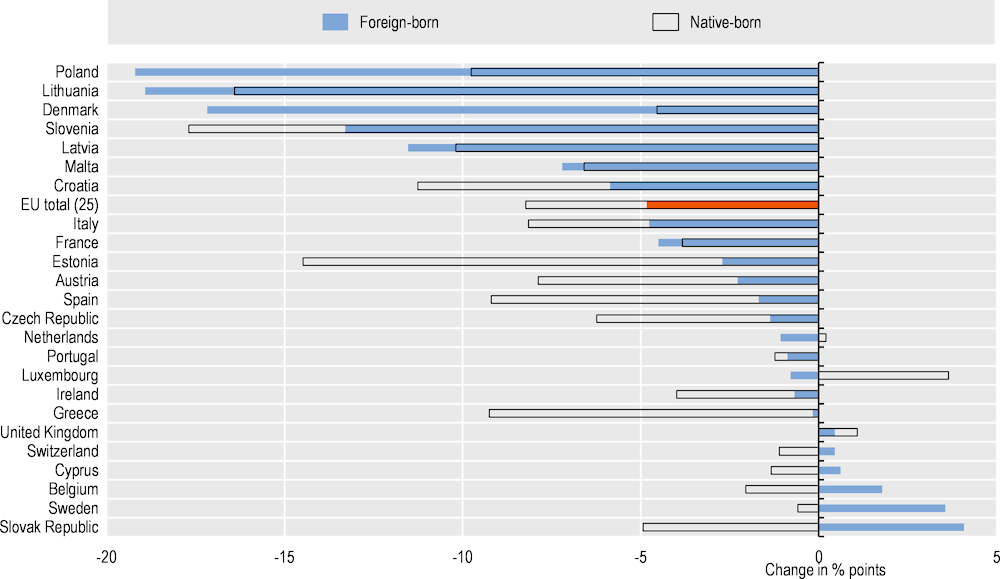

Foreign-born populations are getting older in most OECD and EU countries. The share of the elderly among migrants grew in two‑thirds of countries over the last decade. Aging is however slower than among the native‑born, for which the shares of elderly increased in all countries.

The age structure of immigrants reflects past migration flows, trends in return migration after retirement and mortality patterns. The share of elderly migrants is lowest in countries with comparatively more recent immigration (for example Latin America) and highest in countries where the foreign-born population was shaped by nation-building, border changes and national minorities (such as in the Baltic countries).

Relative poverty rates increased over the last decade while elderly migrants’ housing conditions improved

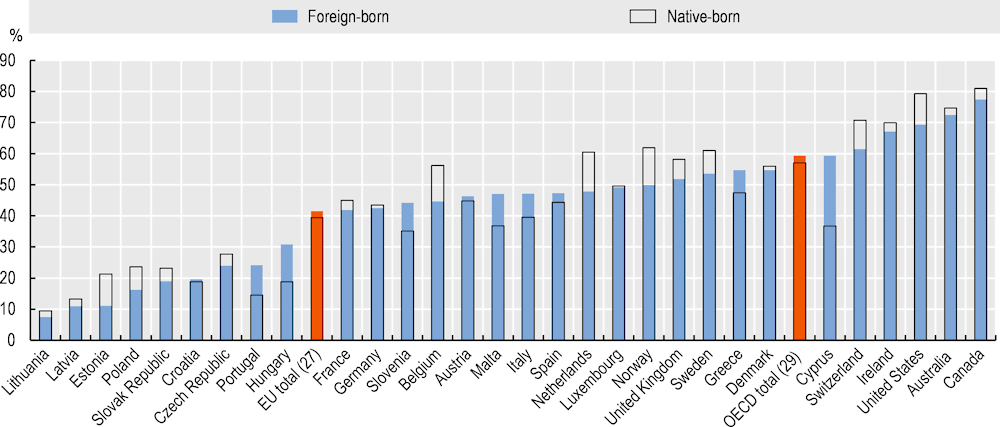

Around one in four elderly migrants lives in relative poverty EU-wide. Shares in the United States and Australia are even higher at over 40%. Elderly migrants are more likely to live in relative poverty than their native‑born peers in most countries, especially in longstanding destinations, the United States, Southern Europe and Sweden. In Malta and Cyprus, which attract wealthy retirees, poverty rates are higher among the native‑born elderly.

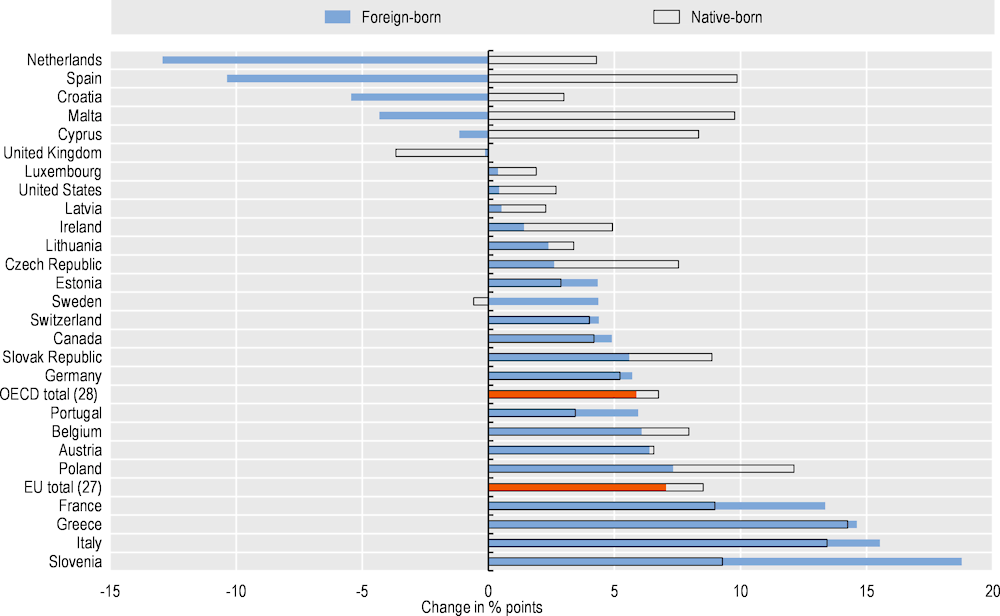

Over the last decade, the poverty rate among elderly migrants has increased by around 4 percentage points, while slightly decreasing among the native‑born in both the EU and the OECD. The situation deteriorated even more among migrants aged 75 years and above.

Housing conditions of the elderly have improved over the last decade. Nevertheless, elderly migrants are more likely than their native‑born peers to live in substandard dwelling in the Czech Republic, Nordic countries and most long-standing destinations, but less likely in the Baltic countries. Non-EU elderly migrants are the most likely to live in substandard accommodation in Europe.

Differences in reported health status and access to care between immigrants and the native‑born are small, but access to professional homecare is an issue for both

In most OECD countries, shares among elderly foreign- and native‑born reporting to be in good health are similar. About 40% of elderly migrants claim they are in good health in the EU. Shares are the highest at over 60% in North America and lowest in the Baltic countries.

Over the last decade, the shares of elderly migrants reporting good health increased in around two‑thirds of countries for the foreign-born and nearly all countries for the native‑born.

Most households with elderly persons in need of professional homecare do not receive such services. Only 34% of households that include elderly migrants in need of such assistance received support, against 36% of the native‑born. Households with elderly migrants were much less likely to receive such support in most Southern European countries and Belgium.

Unlike their native‑born peers, single elderly migrants are less likely to receive professional homecare than those living with other migrant members, while they may be the most in need.

6.1. Age of the immigrant population

Indicator context

Elderly people are those aged 65 years or older. Given that health issues usually arise at an older age, this chapter also considers very old people, i.e. those aged 75 years or older. Shares of elderly people are the percentages of the foreign- and the native‑born populations.

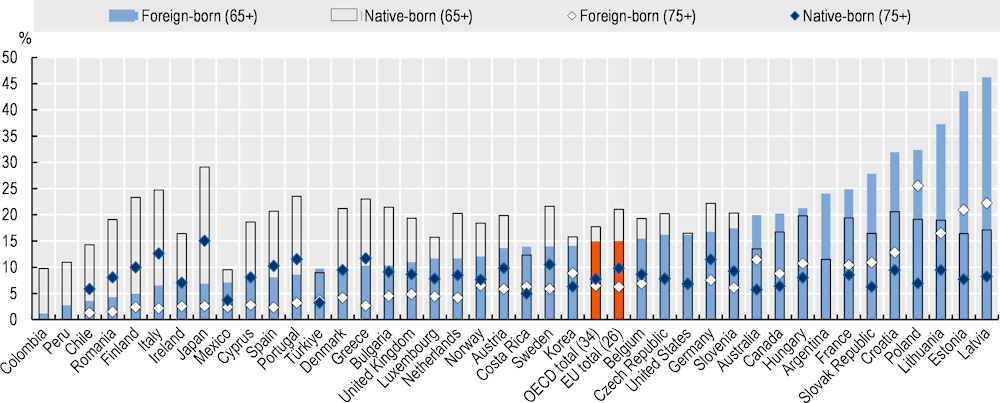

Elderly people (aged 65 and above) account for higher shares of their respective population than their foreign-born peers in both the OECD (18% versus 15%) and the EU (21% versus 15%). Differences are similar in the EU when it comes to very old people (75 and above), who make up 6% of the immigrant population but 10% of the native‑born in the EU. In two‑thirds of countries, the native‑born are more likely to be elderly and very old than the foreign-born. The opposite prevails, however, in most Central and Eastern European countries (where the composition of the elderly foreign-born population has been shaped by nation-building, border changes and national minorities), as well as in Türkiye and some settlement- and long-standing destinations (e.g. Australia, Canada and France). Populations of elderly immigrants are largest in the Baltic countries. In Latvia and Estonia, they account for over 44% of the foreign-born.

The age profiles of the elderly migrant population differ from one country to another, reflecting past migration flows, trends in return migration after retirement, and mortality patterns. In the bulk of OECD countries, elderly migrants are mainly between 65 and 74 years old. OECD- and EU‑wide, 42% of elderly migrants are 75 and over. That share is, however, smaller in countries where significant migration inflows started only in the 2000s and few migrants have reached very old age – as in Southern Europe, Ireland, Mexico and Chile. In Poland, by contrast, where national minorities shaped the foreign-born population after World War II, or in Korea, at least two‑thirds of foreign-born elderly people are very old. In fact, over 15% of elderly migrants are 85 and older in Poland, Bulgaria, Korea and Norway.

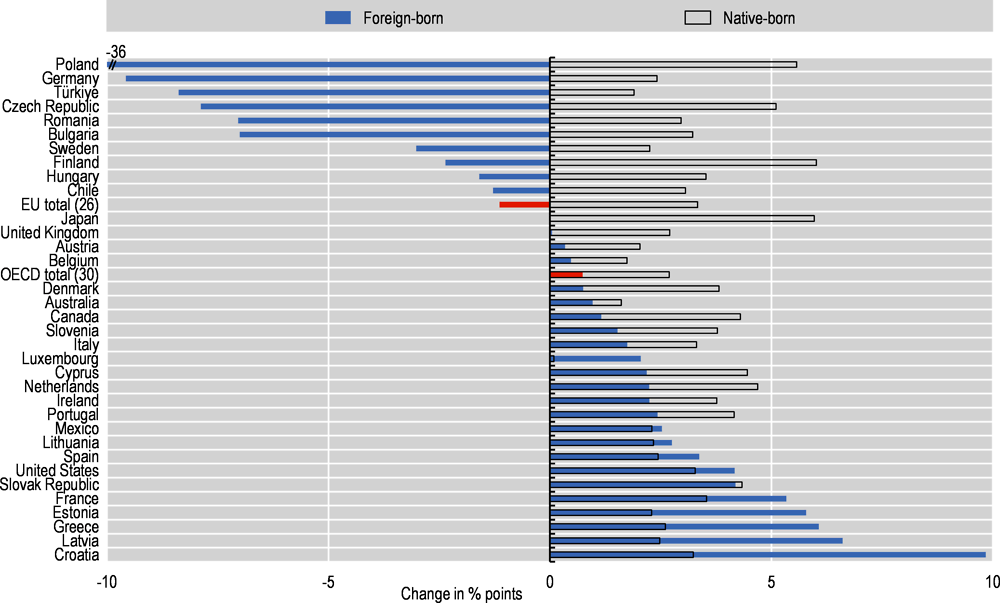

While shares of the elderly and very old native‑born have grown in all countries over the last decade, the same is true of immigrants in only two‑thirds of countries. Increases in shares of elderly people have been stronger among the native‑born in 7 countries out of 10 and, among the very old, in 8 out of 10. However, that is not the case in France, the United States, Greece, the Baltic countries and Croatia. In many other Central and Eastern European countries, shares of elderly and very old migrants have dropped over the last decade, as they have died and younger cohorts of migrants have arrived. Similar trends are observed in most Nordic countries and Chile, albeit to a lesser extent.

Main findings

Shares of the elderly native‑born exceed those of their immigrant peers in two‑thirds of countries in both the EU and the OECD. Cross-country differences in shares of the elderly are much wider among the foreign- than the native‑born.

Elderly migrants are mainly between 65 and 74 years old in most countries. They are older in Poland, Bulgaria, Korea and Norway.

While shares of the elderly native‑born have grown in all countries over the last decade, this is true of immigrants in only two‑thirds of countries.

Figure 6.1. Elderly and very old people

Figure 6.2. How shares of elderly people have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

6.2. Relative poverty

Indicator context

The relative poverty rate is the proportion of individuals living below the relative poverty threshold. The Eurostat definition of that threshold is 60% of the median equivalised disposable income in each country. The rate is computed for the elderly (65 and over) and very old people (75 and over).

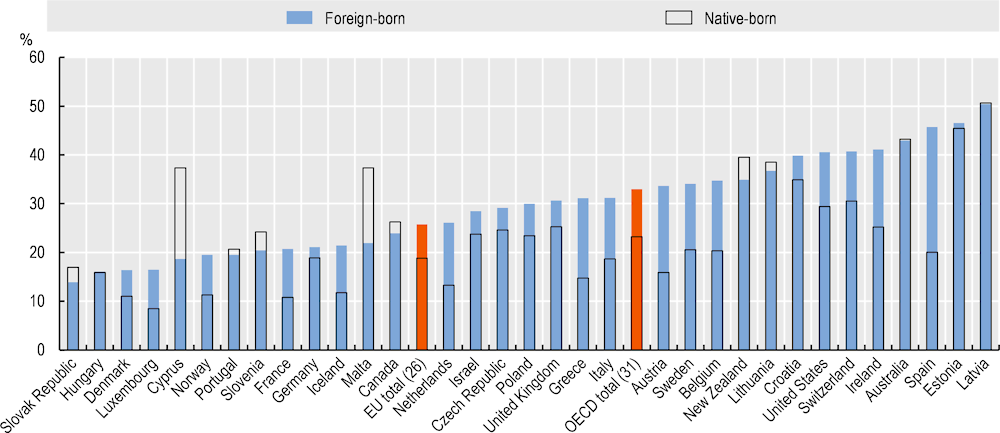

In the EU, 26% of elderly and 28% of very old migrants live in relative poverty, compared to 19% and 22% of their native‑born peers. In the United States and Australia, relative poverty rates exceed 40% among the foreign-born elderly and affect up to 48% of very old migrants in the United States. Indeed, there is more poverty among foreign- than native‑born elderly and very old migrants in most countries – by at least 10 percentage points in longstanding immigration destinations (except Germany and the United Kingdom), the United States, Southern European countries (except Portugal) and Sweden. By contrast, in Malta and Cyprus, which attract many wealthy retirees, the native‑born elderly are more likely to be poor. The native‑born are also significantly more likely to be in relative poverty in Canada, New Zealand, and some Central and Eastern European countries.

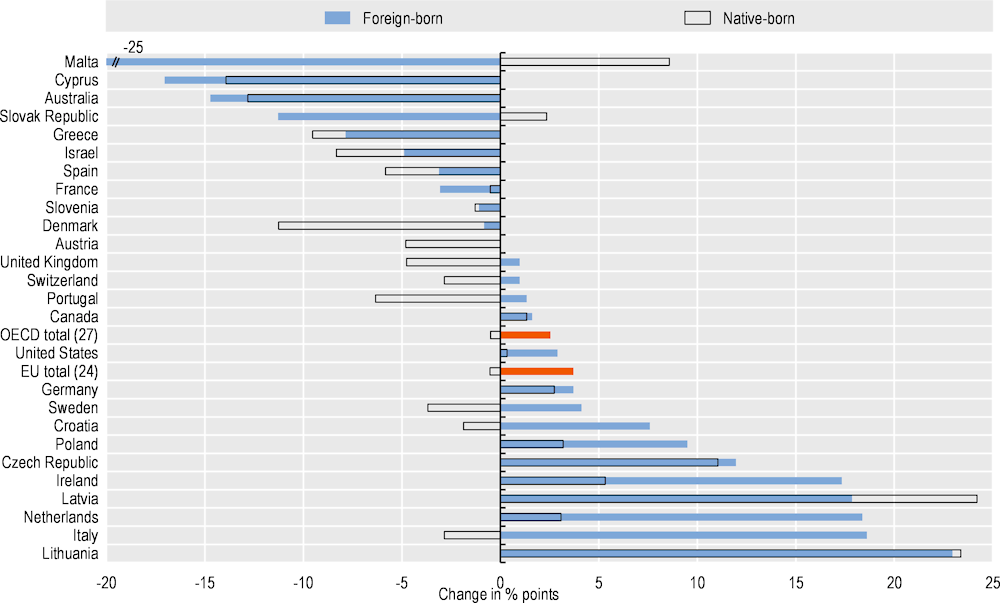

Over the last decade, the poverty rate of elderly migrants has increased by around 4 points, while falling slightly among the native‑born elderly in both the EU and the OECD. It has worsened even more among very old migrants in both the EU and the OECD but declined only slightly among their native‑born peers. Relative poverty rates among elderly have more than doubled among immigrants in Italy and the Netherlands, while decreasing slightly and increasing slightly, respectively, among their native‑born counterparts. In Baltic countries, those rates have risen considerably among the foreign- and native‑born elderly and very old (by at least 18 percentage points), albeit to a greater extent among the native‑born.

Elderly migrants are more likely to be poor than their native‑born peers at all levels of education. Highly educated elderly migrants are more than twice as likely as their native‑born peers to live in relative poverty in the EU, and three times as likely in half of EU countries. Elderly migrants born outside the EU are more likely than their EU‑born counterparts to be poor in virtually all EU countries. Family status, home ownership rates (lower among immigrants), as well as the characteristics of jobs held prior to retirement, are important factors affecting relative poverty.

One‑third of the elderly in the EU, foreign- or native‑born, are living alone, which is true for 22% of foreign- and 29% of native‑born in the United States. The elderly who live alone are even more at risk of poverty, that is around 20 points higher relative poverty rates on average than the rate for the whole elderly migrant population for EU and OECD countries. That penalty is smaller among the foreign-born in most European countries, though not outside Europe. The penalty is heaviest in Central and Eastern Europe. More than 40% of elderly migrants living alone are in relative poverty in slightly less than two‑thirds of countries, while their native‑born peers are poor in around half of countries.

Main findings

In the EU, 26% of elderly migrants live in relative poverty, and even more outside Europe. They are more likely than their native‑born peers to be poor in most countries, especially in longstanding immigration destinations, the United States, Southern Europe and Sweden.

Over the last decade, the elderly migrant poverty rate has increased by around 4 percentage points, while declining slightly among the native‑born elderly in both the EU and the OECD. The situation worsened even more among very old migrants.

Figure 6.3. Relative poverty rates of the elderly

Figure 6.4. How the relative poverty rates of the elderly have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

6.3. Housing conditions

Indicator context

Housing conditions are a key determinant of the well-being of the elderly. Living in substandard accommodation increases the risk of poor health and can lead to social isolation.

This indicator (available for European countries only) shows the share of people aged 65 and above and 75 and above living in substandard accommodation, e.g. too dark, no exclusive access to a bathroom, or leaking roof.

In the EU, one‑sixth of elderly migrants live in substandard housing, a share similar to that of their native‑born peers. The foreign-born elderly are more likely than their native‑born peers to reside in substandard accommodation in 3 countries in 5, especially in the Czech Republic, Nordic countries and most longstanding destinations. While very old migrants (aged 75 and above) are less likely than those aged between 65 and 74 to live in such housing, the very old native‑born are more likely to in virtually all countries. The EU-wide share of very old native‑born in deprived housing is 4 percentage points higher than that of their foreign-born peers. Unlike their peers aged 65 to 74, very old migrants are better housed than the native‑born e.g. in Spain, Austria and France, as are very old and elderly immigrants in the Baltic countries (except Estonia). The same applies to Malta, which hosts many wealthy elderly migrants.

The housing conditions of the elderly have improved over the last decade. In some 3 out of 4 countries, the share of foreign-born elderly people living in deprived accommodation has dropped and, in most countries, to an even larger extent among the very old. The same trend emerges among the native‑born, among whom, the decline tends to be steeper than among the foreign-born elderly (‑8 versus ‑5 percentage points, respectively, EU‑wide), and similarly steep in both groups when it comes to the very old. As a result, the gap between the elderly foreign- and native‑born has widened in some countries.

A lack of financial resources and knowledge of the housing market, as well as discrimination by property owners, may hamper the access of elderly migrants to adequate housing. Such obstacles affect non‑EU elderly migrants more widely than their EU‑born peers and, in virtually every European country, they are more likely to live in substandard accommodation. The accommodation gap exceeds 11 percentage points in Austria, Sweden and the Netherlands. The elderly who live alone are also more likely to reside in substandard housing than the elderly population as a whole for both the native‑ and the foreign-born. Living alone is particularly detrimental to living in good housing conditions for immigrants in Spain, Greece and Slovenia. Furthermore, in virtually all countries, homeownership, which reduces the risk of living in substandard accommodation, is less widespread among the foreign- than the native‑born elderly – 60% versus 85% EU‑wide.

Main findings

Elderly migrants are more likely than their native‑born peers to live in substandard housing in Nordic countries and most longstanding destinations, but less likely in the Baltic countries. Very old migrants are better housed than their peers aged 65 to 74, but very old native‑born are not.

In the EU, the share of elderly migrants living in substandard housing has declined over the last decade, and to an even larger extent among very old migrants. The improvement was even more marked among the native‑born elderly, though similarly marked for the very old people.

Living alone when elderly is associated with poor housing, especially among immigrants.

Figure 6.5. Substandard accommodation of the elderly

Figure 6.6. How the substandard accommodation rates of the elderly have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

6.4. Reported health status

Indicator context

Feeling healthy is associated with better prospects of living independently, engaging in social relationships, and enjoying good quality of life.

This section considers the shares of elderly people (65 and over) and the very old (75 and over) who perceive their general health (physiological and psychological) as “good” or “very good”.

Across the EU, four in ten elderly and three very old migrants in ten report good health – shares similar to those of the native‑born. In North America, Australia, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, elderly immigrants are less likely to report good health than their native‑born peers (even more so when very old), which indicates that old age is associated with a weaker healthy migrant perception (see Indicator 4.9). Poorer health among elderly immigrants is also observed in longstanding European destinations, especially Belgium and the Netherlands. The opposite prevails in Southern Europe, Hungary and Slovenia, where elderly migrants are more likely than their native‑born peers to report good health.

Over the last decade, the share of the elderly reporting good health rose by around 8 percentage points in the EU among both immigrants and the native‑born. Self-perceived health improved among the elderly and very old in around two‑thirds of countries among the foreign-born and in almost every country among the native‑born. The steepest increases in the shares of elderly and very old migrants reporting good health came in Greece, Italy, Slovenia and France – outstripping the elderly native‑born. In the Netherlands and Spain, by contrast, the share of elderly migrants in good health dropped by at least 10 percentage points, while climbing among the native‑born. In the United Kingdom, the decline in self-reported health among the native‑born was not seen among immigrants. In the United States, in contrast, where the situation among the immigrants also remained stable, there was some increase among the native‑born.

Elderly migrants born in the EU are 8 percentage points more likely to report good health than their non‑EU born peers, who generally have fewer financial resources, weaker social networks, and more limited access to healthcare systems. Furthermore, reports of good health are generally more widespread among men than among women in the OECD, irrespective of their place of birth. Living alone is particularly detrimental to health, especially at an older age. In 7 out of 10 countries, self-perceptions of poor health among the elderly living alone are greater among the native‑ than the foreign-born. In countries that once traditionally took in guest workers (such as France and Germany), as well as in parts of Southern Europe, elderly migrants living alone are actually more likely to report good health than other elderly migrants, unlike their native‑born peers everywhere else (except in Latvia and the United States).

Main findings

Two elderly migrants in five claim they are in good health in the EU. Shares are similar to those reporting good health among the native‑born, but are much lower than those of the native‑born in North America and some long-standing European destinations.

Over the last decade, shares of elderly people reporting good health increased in nearly all countries among the native‑born and in around two‑thirds among the foreign-born. The Netherlands and Spain reported substantial declines for foreign-born elderly.

In countries that took in large numbers of “guest workers” (e.g. France and Germany), and Southern Europe, elderly migrants living alone are more likely to report good health than other elderly migrants, while the opposite is true almost everywhere among their native‑born peers.

Figure 6.7. Self-reported good health status of the elderly

Figure 6.8. How shares of aged foreign-born and native‑born in self-reported good health have evolved

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.

6.5. Access to professional homecare

Indicator context

Professional care enables the elderly with disabilities and chronic ill health to keep their autonomy. Receiving such care is strongly associated with better quality of life.

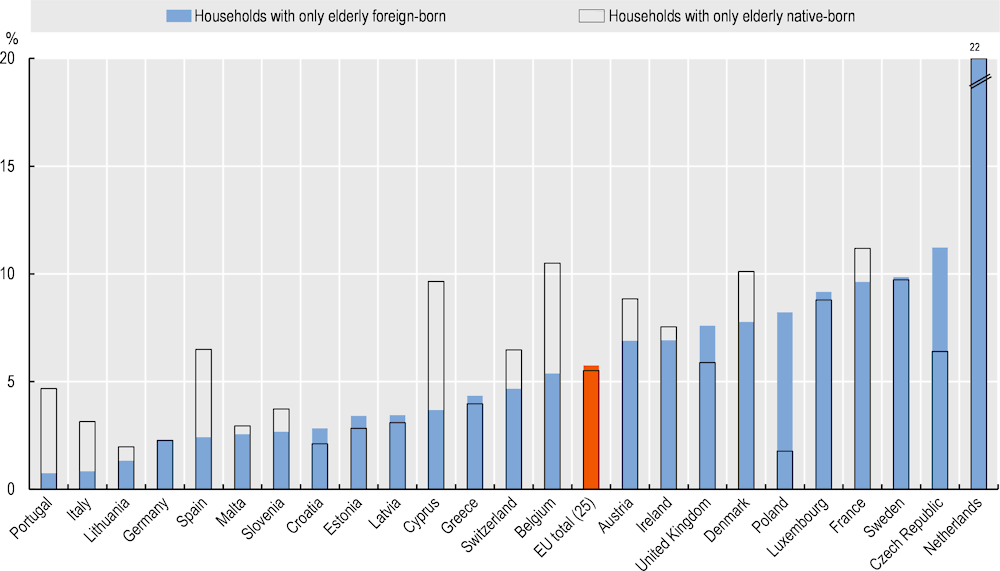

This indicator (only available in Europe and for 2016) shows the share of households with people aged 65 and over and 75 and over who receive professional homecare. Access to professional homecare depends largely on the institutional framework. Unfortunately, there is no country-level information on the elderly in institutional care because household surveys do not cover people living permanently in residential care or nursing homes. Informal homecare is discussed only briefly, as there is no comprehensive measurement of such care at country level and only data on informal homecare provided by other members of the household are available.

Of EU households with elderly immigrant members in 2016, 6% benefited from professional homecare – the same share of households with elderly native‑born people. As for households with very old migrants,13% receive such care. Elderly and very old migrants are more likely than the native‑born to receive professional homecare in one country in four. Elderly migrants are equally likely in Sweden, Germany, and most Central and Eastern European countries. However, households with elderly foreign-born members are less likely to be recipients in other long-standing EU destinations, especially Belgium. This, however, is not the case for very old migrants e.g. in France, where proportionately higher shares benefit from professional homecare than among households with very old native‑born. In most European countries, single elderly native‑born persons are more likely to receive professional homecare than households with many native‑born members. Surprisingly, though, the opposite is the case when it comes to elderly migrants. Exceptions to that trend include the Netherlands, Greece and the United Kingdom.

According to the 2016 European Quality of Life Survey, 41% of the native‑born elderly in the EU who received long-term homecare in the previous 12 months benefited from informal care (mostly from family members, friends, and neighbours), while 54% received professional homecare. Greater shares of migrant than native‑born elderly people accessed professional homecare, with only one‑third receiving informal care at home (though mostly not from family or friends). However, professional homecare is not accessible to most foreign- or native‑born elderly people in need. The EU Survey on Income and Living Conditions finds an average of only 34% of households with elderly migrants in need of professional homecare received it in 2016, against 36% of their native‑born peers. At country level, the share ranges from 60% in France and the Netherlands to 10% in the Baltic countries, with consistently lower shares for households with elderly migrants. In half of all cases, households did not receive professional homecare for their elderly, irrespective of place birth, because they could not afford it.

Main findings

Most households with elderly native‑ or foreign-born members in need of professional homecare do not receive it – and the foreign-born elderly are slightly unlikely to access it.

Households with elderly migrants are at least as likely to receive professional homecare as those with elderly native‑born members in Sweden, Germany, and most Central and Eastern European countries, but much less likely in most Southern European countries and Belgium.

Unlike their native‑born peers, a household consisting of a single elderly migrant is less likely to receive professional homecare than one with multiple migrant members.

Figure 6.9. Professional homecare received

Notes and sources are to be found in the respective StatLinks.