Francesca Borgonovi

Glenda Quintini

Marieke Vandeweyer

Francesca Borgonovi

Glenda Quintini

Marieke Vandeweyer

This chapter starts with an analysis of gender gaps in VET, focusing on gender differences in terms of participation in VET and field-of-study choice. It also provides examples of interventions to encourage all students to pursue studies in the field that interests them. It then focuses on gender differences in VET students’ participation in apprenticeship training. The chapter then analyses gender differences in adult learning participation and presents policies approaches to support adult learning.

Gender differences prevail in terms of participation in VET and field-of-study choice. The share of women learners (typically 16 to 18 years of age) is significantly higher in upper secondary general programmes than in vocational programmes.

Women learners are less likely to pursue technical and engineering VET programmes but more likely to participate in business and administration; and health and welfare programmes than male learners are. They are also less likely to participate in apprenticeship programmes – which in many countries continue to be mostly provided in male‑dominated fields of study, which often lead to higher rates of employment.

Women are less likely to participate in adult education and training among the low-qualified.

VET embraces education, training and skills development in a wide range of occupational fields. VET programmes can include work-based components or be completely school-based, and they typically lead to qualifications that are relevant in the labour market (OECD, 2020[1]). Effective VET systems have a strong connection to the world of work, involving social partners in the design and delivery of VET to ensure that students are equipped with relevant skills and employers find the skills they need. They enhance student engagement in education, resulting in lower school dropout, and facilitate school-to-work transitions.

VET plays a prominent role in education systems in OECD countries. In 2020, on average across OECD countries, 37% of those graduating from upper secondary education for the first-time obtained a vocational qualification, ranging from 5% in Canada to 74% in Austria (OECD, 2022[2]). Short-cycle tertiary education programmes, which are typically vocational in nature and are often two years full-time (e.g. associate degrees in Belgium and the Netherlands, business academy programmes in Denmark, higher technician qualifications in Spain, and higher national diplomas in the United Kingdom), account for 17% of first-time entrants into tertiary education across OECD countries (OECD, 2022[3]).

Young adults with an upper-secondary vocational qualification generally have better labour market outcomes than those with a general qualification at the same level (Vandeweyer and Verhagen, 2020[4]; OECD, 2021[5]). However, this average masks large differences between countries and between VET programmes within countries. Not all fields of study provide the same labour market prospects and not all VET programmes have the same exposure to work-based learning that contributes to smooth school-to-work transitions.

Gender differences prevail in terms of participation in VET and field-of-study choice. The share of women learners tends to be significantly higher in upper secondary general programmes than in vocational programmes. On average across OECD countries, women make up 55% of upper secondary graduates from general programmes, compared to 45% for vocational programmes. Women are under-represented in vocational programmes in almost three‑quarters of the OECD countries with available data (OECD, 2022[2]). However, the opposite holds in programmes at the post-secondary non-tertiary level and the short-cycle tertiary level (OECD, 2022[2]).

Two reasons explain the under-representation of women in upper secondary vocational education but not in post-secondary education. First, women have a higher completion rate for upper secondary vocational education than men and therefore are more likely to continue their studies in post-secondary education. Second, the prevalence of fields of study is often different at the short-cycle tertiary level than at the upper secondary level. Men are more likely than women to enter short-cycle tertiary programmes in countries where Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields are more prevalent at this level. In contrast, where health and education fields are more prevalent, then the share of women increases (OECD, 2020[6]).

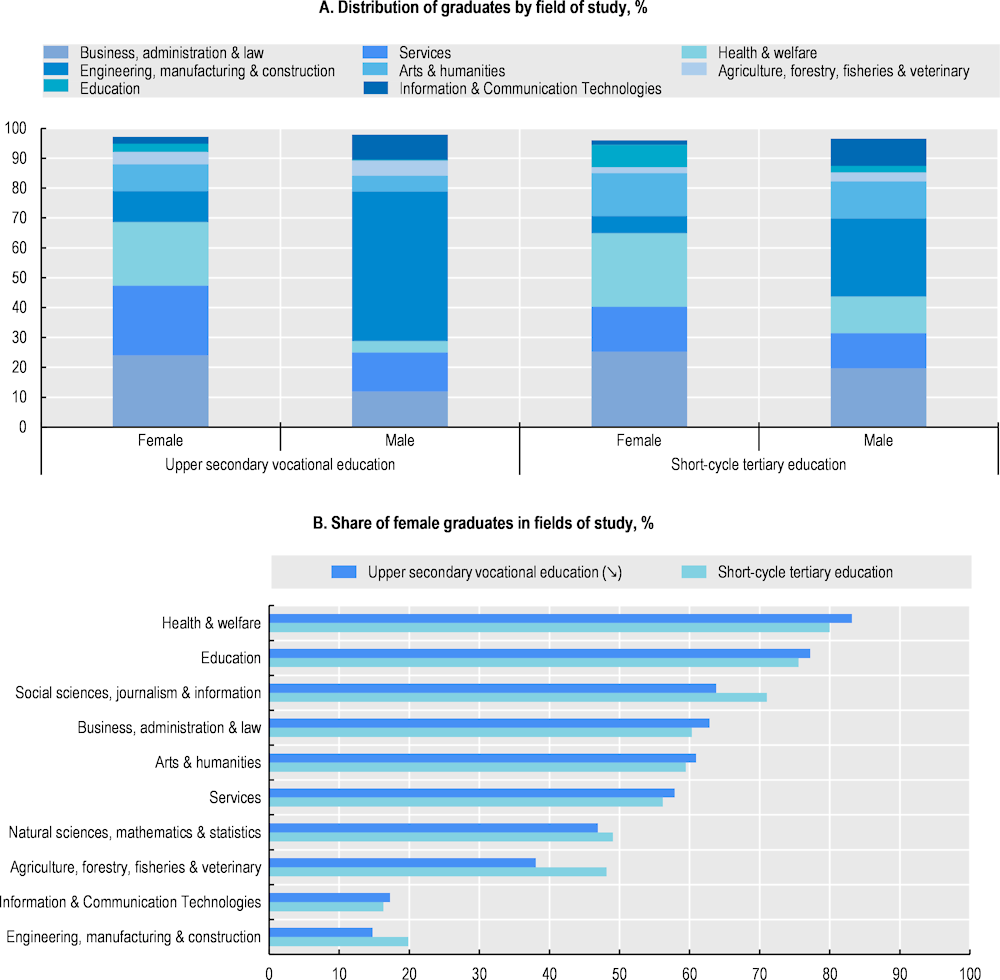

In line with what Chapter 9 showed, gender differences in field-of-study choice in VET are large. Engineering, manufacturing and construction is the most popular field of study among male upper-secondary VET students, but it is much less popular among female students: 50% of male upper-secondary VET graduates come from this field, compared to only 10% of female graduates (Figure 11.1, Panel A). The largest fields of study for women learners are business, administration and law; services; and health and welfare, which jointly account for over two‑thirds of female upper-secondary VET graduates – compared to only 30% of their male counterparts. Women learners are heavily underrepresented not only in the field of engineering, manufacturing and construction (where they account for only 15% of upper-secondary VET graduates), but also in information and communication technologies (ICT) fields (17%) (Figure 11.1, Panel B). By contrast, they are strongly overrepresented in the education field (accounting for 77% of upper-secondary graduates) in addition to the health and welfare field (83%). Similar gender differences are found at the short-cycle tertiary education level.

Gender differences in field of study translate into different occupational employment patterns among young adults with a VET qualification. While crafts and related-trades occupations employ on average around one‑third of young men with non-tertiary VET qualifications, these occupations only account for 4% of employment of their female counterparts. Sales and service jobs are the most important occupations for young women with a VET qualification, accounting for 44% of employment, compared to only 15% among men. Employment in high-skill occupations is slightly more common for young female than for male adults with a VET qualification (22% versus 19%) (OECD, 2020[1]).

Encouraging all students to pursue studies in the field that interests them and in which they can fully express their potential may result in better labour market and social outcomes. Gender stereotyping can deter both girls and boys from pursuing specific careers, especially so in traditional VET occupations, such as manufacturing (Makarova, Aeschlimann and Herzog, 2019[7]). Schools can help students cultivate a wider perspective on different career options, including in traditional VET fields, through better career information and regular career talks and workplace visits. Stereotypes preventing girls to progress in the same fields as boys (and vice versa) can be countered by improved information and career guidance interventions. Providing career guidance at an early stage can help prevent the emergence of stereotypical perceptions of specific educational and career paths (Howard et al., 2015[8]). Evidence from England (United Kingdom) shows that even primary school-aged pupils are already forming ideas about their future careers, and are coming to see some subjects and career paths as not suitable for them (Archer, DeWitt and Wong, 2014[9]).

As relevant examples, Denmark celebrates girls’ day for students from 5th grade by providing information about occupations where women are underrepresented, promoting STEM professions, and offering multiple interactive activities where companies and organisations actively participate. Similarly, in Germany, secondary students celebrate Boy’s Days which are aimed at attracting young males into the types of jobs where their gender is underrepresented, such as kindergarten teacher, nurse and florist. Having “role models” can also encourage students to pursue areas that they might otherwise not consider (Hughes et al., 2016[10]; Musset and Mytna Kurekova, 2018[11]). As such, engaging employers of different sizes and sectors, including successful young entrepreneurs, in career guidance programmes will be useful for students. Nonetheless, career guidance interventions have to be designed carefully to be effective, especially when they involve work placements, because if not well designed, they can exacerbate rather than challenge students’ gender stereotypical trajectories (Osgood, Francis and Archer, 2006[12]).

Note: OECD average based on data from latest available year. Upper secondary vocational education refers to programmes at ISCED Level 3 that are designed for learners to acquire the knowledge, skills and competencies specific to a particular occupation, trade, or class of occupations or trades. Short-cycle tertiary education includes all programmes at ISCED Level 5, irrespective of their orientation – in recognition that the vast majority of programmes at this level are professional at least in some sense (with the exception of the United States where associate degrees include a mix: around 40% of associate degrees are conferred in the field of liberal arts and sciences, general studies and humanities, while the remaining 60% are within applied fields), see OECD (2022[3]) for more details. The fields of “Natural sciences, mathematics and statistics” and “Social sciences, journalism and information” are excluded in Panel A as they represent a very small share of graduates among both genders.

Source: OECD (2022[2]), OECD Education at a Glance database, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

Gender differences in field-of-study choice shape the opportunities men and women have to benefit from high quality work-based learning opportunities. In many countries, apprenticeships are most common in manufacturing, construction and engineering, fields in which women are under-represented. As a result, women seeking a vocational qualification mostly pursue school-based programmes and do not benefit from the advantages of apprenticeship schemes (OECD, 2018[13]). According to data from the 2016 European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) ad-hoc module, young men with an upper-secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary VET qualification as their highest education level are more likely to have been an apprentice (defined by the EU-LSF as “paid working experience that is a mandatory part of the curriculum and lasts at least six months”) than young women with the same educational attainment. Likewise, the United States registered apprenticeship system mainly attracts male students, with only 13% of women learners among active apprentices in the 2021 financial year (US Department of Labor, 2022[14]). In Canada, 11.5% of apprenticeship programme registrations in 2020 were women learners (Statistics Canada, 2022[15]). Women learners accounted for 28% of all apprentices and trainees in Australia in June 2021 (NCVER, 2022[16]).

Work-based learning allows students to acquire practical skills on up-to-date equipment and under the supervision of trainers who are familiar with the most recent working methods and technologies. According to EU-LFS data, a lack of work experience while studying is associated with lower employment rates later in life: 25‑34 year‑olds with vocational upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment who did not gain any work experience during their studies have lower employment rates than those who had some form of work experience in about half of countries, and often by a large margin. Apprenticeships are especially beneficial in this respect: in about half of the countries with available data, the employment rate for 25‑34 year‑olds who completed an apprenticeship is higher than the rate for those who did a mandatory traineeship, worked outside the curriculum, or did not gain any work experience. For example, in Spain, the employment rate for adults who did an apprenticeship is 14 percentage points higher than the rate for those who had work experience outside the curriculum, and 28 percentage points higher than the rate for those who did not have any work experience while studying (OECD, 2020[6]). While these data may suggest that work experience as part of a vocational qualification is valued on the labour market, they will also reflect to some extent differences in employment chances and prevalence of work-based learning by field of study and unobserved personal characteristics such as motivation and the existence of a professional network. Analysis from France that controls for programme and (observed) personal characteristics shows that graduates who pursued an apprenticeship pathway in upper-secondary or post-secondary VET were more likely to be employed in a job relevant to their qualification and were more often employed by the company where they pursued their training than those who pursued the mainly school-based option (that typically involves a short internship) (Couppié and Gasquet, 2021[17]).

Apprenticeships were traditionally rooted in skilled trade and craft occupations in many countries. However, international experience shows that it is possible to expand the approach well beyond these fields and thus extend the benefits of apprenticeships to a more diverse group of learners. Countries that make extensive use of apprenticeships have successfully diversified their coverage. In Germany, for example, the most popular apprenticeship occupations are in the management and retail sector (BIBB, 2021[18]). In Switzerland, upper secondary level apprenticeships are offered in a diverse range of occupations, having diversified beyond fields traditionally targeted by VET (like construction and manufacturing), into all economic sectors. For example, programmes are available in commercial areas (e.g. salesperson, office assistant), healthcare (e.g. medical assistant), culture and media (e.g. interactive media designer), transport and logistics (e.g. logistician), and ICT (e.g. information technologist).

Some countries provide financial incentives to apprentices from the underrepresented gender or to employers taking on these apprentices. In Ireland, for example, employers who recruit female craft apprentices are eligible for a bursary per female apprentice registered. This bursary has recently been expanded to all programmes with greater than 80% representation of a single gender. There are currently 41 apprenticeship programmes that are predominately male, and only one apprenticeship predominately female (i.e. hairdressing) (Government of Ireland, 2022[19]). In Canada, the Apprenticeship Incentive Grant for Women helps female apprentices pay for expenses while they train as an apprentice in a designated trade sector where women are underrepresented.

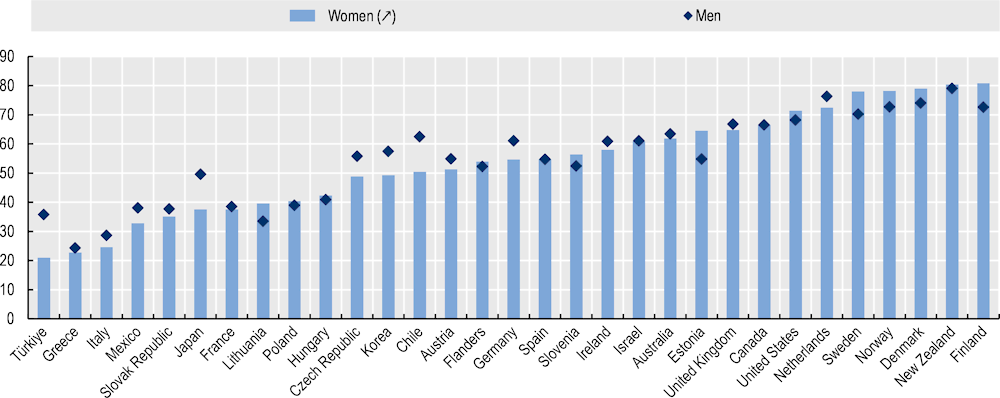

Participating in adult education and training has high benefits in terms of wages and employability, particularly in a context of rapidly changing skill needs. While wages and training participation are positively correlated for all workers, women who participate in job-related non-formal training earn higher wages than their male counterparts (Fialho, Quintini and Vandeweyer, 2019[20]). The gap in participation in adult learning by gender is small on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2019[21]), see Figure 11.2. Among all adults, women are 1 percentage point less likely to participate in training than men. However, this figure hides significant country variation in the size and direction of the gender gap. Women are less likely to participate in adult training than men in Chile, Japan and Türkiye, where the gap exceeds 10 percentage points. However, in Estonia, Finland, Sweden and Lithuania, women are more likely to participate in adult education and training than men.

Note: Data for Mexico and Hungary refer to 2017; data for Israel, Lithuania, New Zealand, Slovenia and Türkiye refer to 2015; data for all other countries refer to 2012.

Source: OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC, 2012, 2015, 2017).

Women are less likely to participate in adult education and training among the low-qualified – defined as individuals who did not obtain an upper-secondary qualification. In the vast majority of countries, low-qualified men train more than their female counterparts do and by a significant margin. In the Czech Republic, the gender gap among the low-qualified is 32 percentage points, in Israel it is 25 percentage points and in Germany 22 percentage points. Only in very few countries, low-qualified women train more than men and the differences is generally small, not exceeding 4 percentage points.

According to data from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills, women are more likely to cite family responsibility and cost as barriers to participation in adult education and training. Making courses shorter, opening up the possibility of online provision and covering the indirect cost of training can contribute to lower the barriers related to time and resource constraints and encourage more women to participate in training, particularly among those with lower education and wages.

Micro-credentials are short, bite‑sized courses, possibly held online, that provide credentials that can be cumulated to achieve a qualification and that are recognised across training providers (OECD, 2021[22]). Modular approaches can provide adult learners with greater flexibility on their learning path and can be combined with processes for the recognition of prior learning. They allow adult learners to focus on developing the skills they currently lack, complete self-contained learning modules on these skills and combine these modules to eventually gain a full (formal) qualification. On the demand side, micro-credentials also guarantee more flexibility in a context of rapidly changing skill needs, particularly when issued by training providers outside the main education system whose curricula can be adapted more easily and promptly to the needs of the labour market.

The provision of short modular courses can broaden access to formal qualifications, in particular for disadvantaged groups (Kis and Windisch, 2018[23]). The Danish adult learning system in particular allows learners a high degree of flexibility. Much of the training provision enables learners to tailor their education and training programme based on their individual needs by combining learning modules from different kinds of provision and across different subjects (Desjardins, 2017[24]). For example, individuals working towards a vocational qualification in Labour Market Training Centres (Arbejdsmarkedsuddannelse) can choose from a wide range of vocational training courses but also tap into subjects provided by the general education system. In Mexico, participants in the Model for Life and Work programme (Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo, MEVyT), which provides learning opportunities for youth and adults to catch up on primary and secondary education, can combine different modules that cover a variety of topics. Some of these modules are delivered on an online platform.

Policies also aim to support adult learning by covering the indirect cost of training, also related to childcare. The Adult Upgrading Grant in British Columbia (Canada) covers additional costs of participating in educational and training programmes, including unsubsidised childcare. In Ireland, under the Childcare Employment and Training Support (CETS) scheme, adult learners can qualify for a subsidised childcare place. CETS can provide full-time, part-time or after-school childcare places. Similar subsidies are available in the United Kingdom for adults in further education. In Austria, the public employment service covers the costs of training and education courses and course‑related costs (e.g. learning materials, specific clothing, accommodation and a family allowance) for job-seekers and employees on low-incomes (Beihilfe zu den Kurskosten/Kursnebenkosten). Allowances for childcare are also common in training targeting lone parents that is provided by the public employment service.

Young learners should have access to high-quality career information and regular career talks and workplace visits that tackle stereotypical perceptions of VET programmes and their related career paths. Such career guidance activities should start at an early age and ideally involve employers from different sectors and sizes.

The use of apprenticeships and similar types of work-based learning opportunities should be extended to a broader set of fields of study, so that a more diverse group of VET learners – including women learners – can reap the benefits of this type of training. Moreover, employers who train apprentices should be encouraged to take on apprentices from the underrepresented gender.

Adult education and training opportunities should be organised in a modular structure with opportunities for the recognition of prior learning to make them more accessible to women learners. Micro-credentials should be developed and linked to national qualifications frameworks. Careful consideration needs to be given to the quality and relevance of the modules and credentials.

[9] Archer, L., J. DeWitt and B. Wong (2014), “Spheres of influence: what shapes young people’s aspirations at age 12/13 and what are the implications for education policy?”, Journal of Education Policy, Vol. 29/1, pp. 58-85, https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.790079.

[18] BIBB (2021), Hitliste der Berufe nach NAA, https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/naa309/naa309_2021_tab067_0bund.pdf.

[17] Couppié, T. and C. Gasquet (2021), “Débuter en CDI: le plus des apprentis”, Céreq BREF, Vol. 406, https://www.cereq.fr/sites/default/files/2021-04/Bref406_web.pdf.

[24] Desjardins, R. (2017), Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474273671.

[20] Fialho, P., G. Quintini and M. Vandeweyer (2019), “Returns to different forms of job related training: Factoring in informal learning”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 231, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b21807e9-en.

[19] Government of Ireland (2022), Minister Harris announces new gender-based funding for apprenticeship employers, https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/2689f-minister-harris-announces-new-gender-based-funding-for-apprenticeship-employers/#.

[8] Howard, K. et al. (2015), “Perceived influences on the career choices of children and youth: an exploratory study”, International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, Vol. 15/2, pp. 99-111, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9298-2.

[10] Hughes, D. et al. (2016), Careers education : international literature review, Education Endowment Foundation, https://www.educationandemployers.org/research/careers-education-international-literature-review/.

[23] Kis, V. and H. Windisch (2018), “Making skills transparent: Recognising vocational skills acquired through workbased learning”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 180, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5830c400-en.

[7] Makarova, E., B. Aeschlimann and W. Herzog (2019), “The Gender Gap in STEM Fields: The Impact of the Gender Stereotype of Math and Science on Secondary Students’ Career Aspirations”, Frontiers in Education, Vol. 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00060.

[11] Musset, P. and L. Mytna Kurekova (2018), “Working it out: Career Guidance and Employer Engagement”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 175, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/51c9d18d-en.

[16] NCVER (2022), Apprentices and trainees 2021: June quarter, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/apprentices-and-trainees-2021-june-quarter.

[2] OECD (2022), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en.

[3] OECD (2022), Pathways to Professions: Understanding Higher Vocational and Professional Tertiary Education Systems, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a81152f4-en.

[22] OECD (2021), “Micro-credential innovations in higher education: Who, What and Why?”, OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f14ef041-en.

[5] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[6] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1686c758-en.

[21] OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

[13] OECD (2018), Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264306486-en.

[12] Osgood, J., B. Francis and L. Archer (2006), “Gendered identities and work placement: why don’t boys care?”, Journal of Education Policy, Vol. 21/3, pp. 305-321, https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930600600424.

[15] Statistics Canada (2022), Table 37-10-0023-01 Number of apprenticeship program registrations, https://doi.org/10.25318/3710002301-eng.

[14] US Department of Labor (2022), FY 2021 Data and Statistics - Registered Apprenticeship National Results Fiscal Year 2021, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/apprenticeship/about/statistics/2021.

[4] Vandeweyer, M. and A. Verhagen (2020), “The changing labour market for graduates from medium-level vocational education and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 244, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/503bcecb-en.