David Halabisky

María Camila Jiménez

Miriam Koreen

Marco Marchese

Helen Shymanski

David Halabisky

María Camila Jiménez

Miriam Koreen

Marco Marchese

Helen Shymanski

Women entrepreneurs have long faced barriers in access to finance for business creation and growth. This chapter presents data on the barriers faced by women entrepreneurs and highlights recent public policy measures that aim to address the gender gap in entrepreneurship finance. The chapter discusses the need to increase the use of microfinance to support business creation by women and improve the quality of accompanying non-financial services. It also covers the potential of fintech to improve access to debt and equity financing and the need to scale up measures to support growth-oriented women. The chapter underlines the need for more action in the collection of gender-disaggregated data to support policy making. It then presents key policy messages on future directions for public policy.

Women entrepreneurs continue to face greater difficulties in accessing finance to start a business than men due to a range of supply-side issues (e.g. financial products and services that are not suitable for the types of businesses led by women, unconscious bias among lenders and investors) and demand-side factors (e.g. lower levels of financial literacy).

Traditional government measures to support women entrepreneurs include loan guarantees and grants. The use of microfinance schemes is growing in some OECD countries, notably in Eastern Europe. Moreover, offers are becoming more sophisticated and increasingly bundled with professional non-financial services. However, substantial unmet demand for microfinance remains, especially in the European Union (EU), and there is a need to improve the quality of non-financial services provided.

Two emerging policy approaches that facilitate access to finance for women entrepreneurs are gaining traction. First, fintech is increasingly viewed as a tool to address finance gaps for women entrepreneurs. This includes new financial markets such as crowdfunding platforms where women entrepreneurs have been very successful, as well as innovations (e.g. big data) that inform investing and lending decisions. In addition, governments continue to increase investments that support growth-oriented women entrepreneurs. This includes equity instruments as well as building networks of female investors.

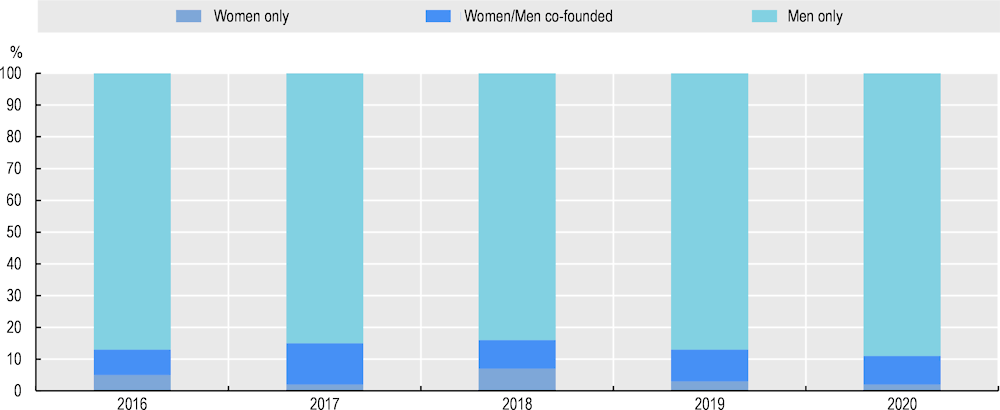

Women entrepreneurs have long faced barriers in accessing finance for business creation and growth (OECD/European Commission, 2021[1]) and are less likely to successfully access debt and equity financing than their male counterparts. When they do, they typically receive less funding, pay higher interest rates and are required to provide more collateral (Lassébie et al., 2019[2]; Thebaud and Sharkey, 2016[3]). For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, women owned micro‑enterprises receive USD 5 billion (EUR 4.7 billion) less in financing than those owned by men, while the finance gap between women-owned and men-owned SMEs reached USD 93 billion (EUR 86.6 billion) (UN Women, 2021[4]). This gender gap is particularly noticeable among growth-oriented businesses, notably in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) sectors, where women entrepreneurs are under-represented (OECD, 2021[5]). Businesses owned or led by women receive only about 2% of total venture capitalist investments (Figure 29.1). Moreover, women entrepreneurs who acquire venture capital investment only receive about 70% of the funding that men receive on average (Lassébie et al., 2019[2]). Addressing long-standing barriers for women entrepreneurs to access finance could create USD 5‑6 trillion (EUR 4.7‑5.6 trillion) in potential net value addition worldwide (Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, 2022[6]). For financial institutions, this could represent a USD 1.7 trillion (EUR 1.6 trillion) in growth opportunity (International Finance Corporation, 2017[7]).

Gender gaps in access to finance are often due to institutional and market failures on both sides of financial markets, as well as to specific characteristics of women-owned firms (size, sector, age of the firm). Supply-side factors include gender biases in lending practices and investor preferences, largely due to the small number of women investors and lenders. For example, women represent nearly 40% of the top wealth holders in the United States yet only account for 19.5% of angel investors (Jeffrey Sohl, 2018[8]). Other factors include a mismatch of financial products and services for the needs of women-led businesses and unconscious bias from those assessing funding proposals (Halabisky, 2015[9]). On the demand-side, women entrepreneurs, on average, have lower levels of financial literacy than men (Chapter 12). This can reduce their ability to identify funding opportunities for their businesses and can also negatively impact how they pitch their business to lenders and investors (Halabisky, 2015[9]).

Note: Start-ups without founders listed in the Crunch base system were excluded from the dataset. Private equity is also excluded.

Source: Teare (2020[10]), Global VC Funding to Female Founders Dropped Dramatically this Year, https://news.crunchbase.com/news/global-vc-funding-to-female-founders/.

Governments can play an important role in supporting a more diverse and inclusive entrepreneurship pipeline by doing more to address the gender gap in entrepreneurship finance. It is important for governments to utilise the entire range of financial instruments available to support the wide spectrum of women-led businesses, as the needs and challenges experienced by women entrepreneurs and potential entrepreneurs vary depending on an array of factors (e.g. type of business, sector of operation, size of business, growth objectives, etc.). Traditional policy responses include loan guarantees, grants and investor readiness training (OECD/European Commission, 2013[11]) but the governments’ toolkit is growing.

Microfinance is an important financial tool for people who experience financial exclusion from mainstream financial markets. While microfinance is commonly offered through dedicated microfinance institutes (MFIs) in developing countries, it is increasingly used to support business creation in many OECD countries, particularly in eastern European Union Member States and in Central and South American countries. Women are the most significant target client group for MFIs, accounting for as much as 80% of microfinance borrowers in developing countries (Sweidan, 2016[12]) and nearly 60% in the EU (Corsi, 2021[13]). The total global loan portfolio is currently estimated to be about USD 145‑160 billion (approximately EUR 124‑137 billion) (MEDICI, 2021[14]; ReportLinker Consulting, 2021[15]) and this could grow to reach about USD 400 billion (approximately EUR 342 billion) by 2027 (ReportLinker Consulting, 2021[15]).

Governments can do more to improve access to finance for women entrepreneurs by strengthening microfinance markets. There is significant unmet demand for microfinance for entrepreneurship, especially in the EU where the market gap is expected to grow to nearly EUR 17 billion by 2027 (Drexler et al., 2020[16]). A short-term priority is to inject more capital into the microfinance sector, which was heavily impacted by the COVID‑19 pandemic (Box 29.1). Several options are available to governments to increase the supply of microfinance, including providing more dedicated funding for microfinance schemes for women entrepreneurs, increasing guarantees to MFIs so that they lend more and offering greater incentives to attract new entrants into the microfinance market (OECD/European Commission, 2021[1]), providing funds for microfinance with softer conditions (e.g. longer term maturities) and offering relief to MFIs by deferring non-critical supervisory processes.

In addition, governments can offer technical support to MFIs to strengthen their non-financial services offer and improve the efficiency of their business models. The vast majority of MFIs in OECD countries bundle microloans with a variety of non-financial services, such as training and coaching that aim to improve the performance of the business to increase the chances of the microloan being repaid. Evaluations tend to show that these non-financial services are effective (OECD/European Commission, 2021[1]) but many offers are relatively basic (Drexler et al., 2020[16]) and are less commonly offered by MFIs in certain regions (e.g. Eastern Europe) (Diriker, Landoni and Benaglio, 2018[17]). These non-financial services are typically more impactful for women entrepreneurs given their relatively greater skills gaps and, on average, a lack of professionals in their networks (Halabisky, 2015[9]). In addition, the business practices of MFIs could go further in leveraging digital tools to improve the efficiency of internal business processes. For example, the introduction of an electronic signature or “e‑signature” by Adie in France has reduced loan processing times and accelerated the disbursement of funds (OECD/European Commission, 2021[1]).

The microfinance sector experienced several immediate challenges in the wake of the COVID‑19 pandemic, notably short-term liquidity pressures. Both the demand (i.e. client repayments) and supply (i.e. access to capital and liquidity) sides of the market were impacted and many MFIs have responded by adjusting their products and services. This includes introducing new products to provide liquidity, providing greater support for the pivoting of business activities (e.g. reduced administrative fees, training) and offering business support services (e.g. training, coaching and mentoring) through online platforms to ensure continuity while social distancing measures were in place. Public funding has supported many of these new offerings. For example, the Government of Italy introduced several policy actions to mitigate the impact of COVID‑19 on the microcredit sector, including, a moratorium on loan repayments, loan guarantees of up to 80% of the loan amount and an increase in the maximum loan amount of business microcredits from EUR 25 000 to EUR 40 000.

Source: OECD/European Commission (2021[1]), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2021: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment, https://doi.org/10.1787/71b7a9bb-en.

The rapid evolution of fintech in recent years is creating new funding opportunities for women entrepreneurs and others that have difficulties accessing funding in traditional markets. This includes new debt and equity instruments, new actors such as online challenger banks (i.e. new banks that typically rely on fintech products and services to compete with traditional banks), new marketplaces (e.g. online crowdfunding platforms) and the digital transformation of private equity instruments (i.e. digitalisation of investment assessment and monitoring, including the influence on investor objectives) (Halabisky, 2015[9]). Fintech innovations also include new data analytical possibilities (e.g. big data) and distributed ledger technologies (e.g. blockchain) that can inform new methods of evaluation of loan and investment opportunities.

Women entrepreneurs have been successful in many of these new fintech markets. They appear to be more successful than male entrepreneurs on crowdfunding platforms (Wesemann and Wincent, 2021[18]; Johnson, Stevenson and Letwin, 2018[19]). Research suggests that this is due to women entrepreneurs being more active in crowdfunding markets relative to traditional financing markets and “activist homophily”, i.e. women investors support female‑led projects over male‑led projects (Greenberg and Mollick, 2017[20]).

Despite some of these successes, there is a risk that fintech may reinforce financial exclusion for women entrepreneurs due to a greater reliance on algorithms in decision making by lenders and investors. Such algorithms are likely embedded with the unconscious gender biases of those who are designing, coding and using them – often men (Halabisky, 2015[9]). A greater use of algorithms could also direct funding away from projects that do not seek to generate high levels of growth and profits, putting women entrepreneurs at a disadvantage because they tend to operate small and less growth-oriented businesses (Halabisky, 2015[9]). In addition, there will be fewer opportunities for entrepreneurs, lenders and investors to have face‑to-face interactions where “soft” information can be exchanged. This removes opportunities for lenders and investors to learn about entrepreneurs, their motivations and ambitions and gives greater weight to financial history and collateral, which also puts women entrepreneurs at a disadvantage (Malmström and Wincent, 2018[21]). This also reduces the ability of women entrepreneurs to acquire knowledge through interactions with lenders and investors, a potential source of coaching. This is likely more significant for women entrepreneurs since they, on average, have greater knowledge and skills gaps (OECD/European Commission, 2021[1]) and fewer opportunities to acquire such knowledge in their networks (Halabisky, 2015[9]).

It is, therefore, important that governments do more to monitor developments in fintech to ensure that they contribute to financial inclusion. This includes supporting research projects that monitor and measure discrimination in the financial sector – as done by the Swedish Innovation Agency (VINNOVA) – and ensuring that financial regulators effectively balance the need to protect consumers and the integrity of financial systems without stifling innovation. Governments can also do more to equip women entrepreneurs to be able to leverage the new opportunities offered by fintech by investing more in financial literacy training and entrepreneurship education such as the Power for Entrepreneurs initiative in Spain (Box 29.2), covering new issues such as crowdfunding and blockchain in entrepreneurship training. Another approach is to provide support to existing infrastructures that utilise industry expertise to support women entrepreneurs already in fintech fields, such offering dedicated technology incubation and accelerator programmes for women entrepreneurs (Halabisky, 2015[9]). The WILLA Women in Fintech accelerator programme in France was created after research found that start-ups with at least one female founder performed 63% better than those founded exclusively by men, but only 1 in 10 fintech start-ups were founded by women in 2018 (WILLA, 2018[22]).

The United States Embassy in Madrid and the United States Consulate General in Barcelona, in collaboration with the Sevillian One to Corp consultancy company, held “Power for Entrepreneurs” (POWER para EMPRENDEDORAS) in Summer 2021. This is part of a larger project on “Providing Opportunities for Women’s Economic Rise Initiative”, launched by the Academy of Women Entrepreneurs (AWE), which aims to support the female entrepreneurial ecosystem in Spain. Power for Female Entrepreneurs was designed for women entrepreneurs to participate in an e‑commerce and digital marketing bootcamp, providing women with learning and networking opportunities. Women entrepreneurs from across Spain were able to connect with the larger AWE entrepreneurial network, including over 7 000 entrepreneurs across 80 countries as well as local networks across Spain. Entrepreneurs were also able to participate in a competition after carrying out a micro-test and creating a video. There were eight prizes available, including a Digital Marketing programme in English entirely financed by the US Embassy.

Source: US Embassy and Consulate in Spain and Andorra (2021[23]), Power for Entrepreneurs.

Governments are increasingly supporting strategies and initiatives that address the gender gap in access to finance for growth-oriented women entrepreneurs. Two broad approaches are observed across OECD countries. The first approach is to offer support through direct funding instruments to women founders. An example is the Women in Technology Venture Fund (Canada) that was launched in 2018. The Business Development Bank of Canada manages the Fund, which invests in women-led technology companies in the seed to series B investment stages (i.e. from the first official equity funding stage to the second round of funding). The current portfolio is CAD 200 million (EUR 138 million), and investments have been made in more than 30 women-led companies (BDC, 2022[24]). Similarly, the Female Founders Initiative was launched in Australia in 2020 (Box 29.3) and other more established initiatives such as Enterprise Ireland’s Competitive Start-Fund for Female Entrepreneurs were significantly scaled-up in recent years. The latter provides EUR 50 000 in equity funding to female‑led early-stage start-ups that have the potential to employ more than ten people and achieve EUR 1 million in export sales within three years. The size of the fund has doubled since 2016, reaching EUR 1 million in 2020 (Enterprise Ireland, 2021[25]).

The Government of Australia introduced the Boosting Female Founders Initiative through the 2018 Women’s Economic Security Statement and expanded it through the 2020 Women’s Economic Security Statement. The Initiative seeks to boost the economy through increasing the diversity of start-ups and encouraging private sector investments into innovative women-led start-ups by providing targeted support to women entrepreneurs that wish to scale into domestic and global markets. The programme provides matched funding grants, allowing women founders to apply for grants ranging between.

AUD 25 000 to AUD 400 000 (EUR 160 000 to EUR 257 000) for Rounds One and Two. In Round Three, grants of AUD 100 000 to 400 000 (EUR 64 000 to EUR 257 000) are available. More generous matched funding is available (up to AUD 480 000 or EUR 309 000) for those who face additional barriers, such as women who are regional, rural or remote founders; those who identify as being Indigenous Australian; humanitarian migrant and refugee founders; and founders with a disability. Across the first two rounds of the Boosting Female Founders Initiative, AUD 23 million.

(EUR 14.8 million) in funding was awarded to 89 companies. The third round opened in May 2022 and has AUD 11.6 million (EUR 7.3 million) in grant funding available. The Initiative also provides access to expert mentoring and advice to help women entrepreneurs grow and scale their start-ups.

Source: Government of Australia (2022[26]), Funding for female founders of startup businesses to scale their startups into domestic and global markets, https://business.gov.au/grants-and-programs/boosting-female-founders-initiative-round-3.

Governments also appear to be taking a more active role in supporting investor networks for women to encourage more investment in women entrepreneurs. Many such programmes combine education, networking and direct investments to support the creation of female investor networks. For example, the Women Business Angels for Europe’s Entrepreneurs (WA4E) was launched in 2017 to increase the presence and action of women in business angel financing market in several countries (e.g. Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom), generating over EUR 20 million in angel financing by women (Tooth, 2018[27]; BAE, 2022[28]).

There have been increasing efforts at both national and international levels to better understand the gender dimension in access to finance. A 2022 pilot initiative in the context of the OECD flagship Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs: An OECD Scoreboard, showed that only very few countries collect traditional SME financing indicators by gender of the business owner (OECD, 2023[29]). In 2013, the G20 recognised the importance of data collection and analysis as a priority action in addressing the SME finance gender gap and developed a basic set of gender-disaggregated financial indicators, as part of the G20 Global Partnership on Financial Inclusion (GPFI) and its SME Finance Subgroup indicators (World Bank, 2020[30]). The 2022 Updated G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing also call for gender-disaggregated data collection (OECD, 2022[31]).

Several country-level initiatives are underway to leverage better data collection in order to strengthen women entrepreneurs’ access to finance. For example, the Investing in Women Code is a public commitment launched by the UK Government to support the advancement of female entrepreneurship by improving their access to tools, resources and finance from the financial services sector. Signatory financial institutions commit to collating and publishing a set of financing data by the gender of the business owner (GOV.UK, 2019[32]) (Box 29.4). This builds on earlier experiences, including efforts in Mexico to collect gender-disaggregated data in supply- and demand-side financial inclusion surveys progressively since 2012. In 2014, the Mexican Government approved the Financial Reform law, with the mandate to promote gender equality in access to financial services and in programmes led by national development banks (Data2x, 2019[33]).

In 2019 the UK Government asked Alison Rose, CEO of commercial and private banking at the Royal Bank of Scotland and one of the leading British businesswomen, to undertake a review of the barriers faced by women entrepreneurs in the United Kingdom. The review confirmed many of the barriers preventing women from starting and growing their business in the United Kingdom: the starting capital of British women entrepreneurs is only half that of men; 55% more women than men cite the fear of starting a business alone as a constraint; and women spend 50% more time on childcare than men.

In response, the UK Government developed the Investing in Women Code, which aims to strengthen the quantity and quality of information on gender gaps in access to finance and mobilise financial institutions to help bridge this gap. Signatory financial institutions commit to:

Nominating a member of the senior leadership team who is responsible for supporting equality in all its interactions with entrepreneurs.

Providing HM Treasury, or a relevant industry body designated by HM Treasury, a commonly agreed set of data concerning all-female‑led businesses; mixed-gender-led businesses and all-male‑led businesses.

Agreeing that these data can be published by HM Treasury in aggregated and anonymised form.

Adopting internal practices to improve the potential for female entrepreneurs to successfully access the tools, resources, investment and finance they need to build and grow their businesses.

As of early 2023, 79 financial institutions had signed up to the Code.

Source: GOV.UK (2019[32]), Investing in Women Code, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/investing-in-women-code.

The Women Entrepreneurs Finance (We‑Fi) Code is a global multi-stakeholder effort which follows the UK example by seeking to expand the quality and quantity of data on women-led firms’ financing across a larger group of countries. Other initiatives that work towards improving the collection of gender-disaggregated data include the Alliance for Financial Inclusion, which developed a data portal to include financial inclusion data from financial institutions of around 65 countries (World Bank, 2020[30]). The Women’s Financial Inclusion Data Partnership is an alliance between the Inter-American Development Bank, the Data 2X and the Global Banking Alliance that aims to increase the production, availability, and use of gender-disaggregated data on both supply and demand of financial services. At the moment of writing, the initiative has undertaken pilot projects in six developing countries to support the development of supply-side interventions (Data2x, 2023[34]).

In addition to the OECD, through its SME and entrepreneurship financing Scoreboard, other international organisations have initiatives to include gender elements in their datasets and improve the collection of gender SME finance data; these include the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the EBRD Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Surveys, and the IMF Financial Access Survey (World Bank, 2020[30]).

Governments should continue to use, scale up and further develop the suite of traditional policy measures (e.g. loan guarantees, investor readiness training) to address persistent barriers faced by women entrepreneurs on both the supply-side (e.g. under-representation of female decision makers and mismatch of financial products and services) and demand-side (e.g. low levels of financial literacy) of financial markets.

Governments should explore additional approaches to improve access and increase the supply of finance available to women entrepreneurs, including microfinance and fintech, with due consideration to ensure sufficient supply and strengthen financial inclusion. It is also important to increase the supply of growth financing for high-potential women entrepreneurs (e.g. dedicated funds with competitive selection mechanisms) and to offer non-financial supports such as management training when relevant.

Better collection of data on access to debt and non-debt finance by women entrepreneurs is critical to understand persistent gender gaps and to better tailor financial support.

[28] BAE (2022), WA4E - Women Business Angels for Europe’s Entrepreneurs, https://www.femmesbusinessangels.org/en/women-business-angels/about-us/ (accessed on 12 April 2022).

[24] BDC (2022), Women in Technology Venture Fund, https://www.bdc.ca/en/bdc-capital/venture-capital/funds/women-tech-fund (accessed on 12 April 2022).

[13] Corsi, M. (2021), European Microfinance Survey 2018-2019.

[34] Data2x (2023), Women Financial Inclusion Data Partnership, https://data2x.org/financial-inclusion/.

[33] Data2x (2019), Enabling Women’s Financial Inclusion through Data: The Case of Mexico, https://data2x.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/WFID-Mexico-Case-Study_FINAL.pdf.

[17] Diriker, D., P. Landoni and N. Benaglio (2018), Microfinance in Europe: Survey Report 2016-2017, European Microfinance Network / Microfinance Centre.

[16] Drexler, B. et al. (2020), Microfinance in the European Union: Market analysis and recommendations for delivery options in 2021-2027, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/005692.

[25] Enterprise Ireland (2021), Competitive Start Fund - Women Entrepreneurs.

[32] GOV.UK (2019), Investing in Women Code, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/investing-in-women-code.

[26] Government of Australia (2022), Funding for female founders of startup businesses to scale their startups into domestic and global markets, https://business.gov.au/grants-and-programs/boosting-female-founders-initiative-round-3 (accessed on 13 January 2023).

[20] Greenberg, J. and E. Mollick (2017), “Activist Choice Homophily and the Crowdfunding of Female Founders”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 62/2, pp. 341-374, https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216678847.

[9] Halabisky, D. (2015), “Entrepreneurial Activities in Europe - Expanding Networks for Inclusive Entrepreneurship”, OECD Employment Policy Papers, No. 7, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jrtpbz29mjh-en.

[7] International Finance Corporation (2017), MSME Finance Gap: Assessment of the shortfalls and opportunities in financing, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/03522e90-a13d-4a02-87cd-9ee9a297b311/121264-WP-PUBLIC-MSMEReportFINAL.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=m5SwAQA.

[8] Jeffrey Sohl (2018), “The Angel Market in 2017: Angels Remain Bullish for Seed and Start-Up Investing”, Center for Venture Research, Vol. 16.

[19] Johnson, M., R. Stevenson and C. Letwin (2018), “A woman’s place is in the… startup! Crowdfunder judgments, implicit bias, and the stereotype content model”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 33/6, pp. 813-831, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.003.

[2] Lassébie, J. et al. (2019), “Levelling the playing field : Dissecting the gender gap in the funding of start-ups”, OECD Science Technology and Industry Policy Paper, No. 73, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/23074957.

[21] Malmström, M. and J. Wincent (2018), “The Digitization of Banks Disproportionately Hurts Women Entrepreneurs”, Harvard Business Review.

[14] MEDICI (2021), Understanding the Microlending Landscape: Slow but steady growth.

[29] OECD (2023), “OECD Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs Scoreboard: 2023 Highlights”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 36, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8d13e55-en.

[31] OECD (2022), 2022 Updated G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/2022-Update-OECD-G20-HLP-on-SME-Financing.pdf.

[5] OECD (2021), Entrepreneurship Policies through a Gender Lens, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/71c8f9c9-en.

[1] OECD/European Commission (2021), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2021: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/71b7a9bb-en.

[11] OECD/European Commission (2013), The Missing Entrepreneurs: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship in Europe, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264188167-en.

[15] ReportLinker Consulting (2021), Global Microfinance Industry, https://www.reportlinker.com/p05799111/Global-Microfinance-Industry.html?utm_source=GNW (accessed on 22 September 2021).

[12] Sweidan, M. (2016), A Gender Perspective on Measuring Asset Ownership for Sustainable Development in Jordan, United Nations, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/finland_oct2016/documents/jordan_paper.pdf.

[10] Teare, G. (2020), Global VC Funding to Female Founders Dropped Dramatically this Year, https://news.crunchbase.com/news/global-vc-funding-to-female-founders/.

[3] Thebaud, S. and A. Sharkey (2016), “Unequal Hard Times: The Influence of the Great Recession on Gender Bias in Entrepreneurial Financing”, Sociological Science, Vol. 3, pp. 1-31, https://doi.org/10.15195/v3.a1.

[27] Tooth, J. (2018), The Barriers and Opportunities for Women Angel Investing in Europe, UK Business Angels Europe.

[4] UN Women (2021), Investing in women: a profitable path to empowerment and equality, https://lac.unwomen.org/en/noticias-y-eventos/articulos/2021/05/invertir-en-las-mujeres-un-camino-rentable-al-empoderamiento-y-la-igualdad (accessed on 13 January 2023).

[23] US Embassy and Consulate in Spain and Andorra (2021), Power for Entrepreneurs.

[18] Wesemann, H. and J. Wincent (2021), “A whole new world: Counterintuitive crowdfunding insights for female founders”, Journal of Business Venturing Insights, Vol. 15, p. e00235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2021.e00235.

[22] WILLA (2018), The Willa Manifesto, For Inclusive Growth, https://hellowilla.co/le-manifeste-willa/ (accessed on 30 November 2022).

[6] Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative (2022), The case for investing in women entrepreneurs, https://we-fi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/We-Fi-Case-for-Investment.pdf.

[30] World Bank (2020), G-20: Data enhancement and coordination in SME Finance Stocktaking Report, https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/g20_SME_stock_2020.pdf.