The economy rebounded robustly in the wake of the pandemic, but inflation rose rapidly amid supply constraints and rising global energy prices, leading to a substantial tightening in monetary policy. The public finances have also recovered quickly, but deficits are anticipated to re-emerge in the coming years and there are longer-term fiscal pressures on the horizon related to an ageing population. In response, tax and spending reforms that promote fiscal sustainability are a priority. As the population ages and the economy is shaped by global forces including the climate transition and digitalisation, policies must continue to promote an adaptable labour force and business sector. Reforms in the areas of immigration, education and the regulatory environment will be particularly important.

OECD Economic Surveys: Australia 2023

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

Introduction

Buoyed by pent-up demand, supportive macroeconomic policies and rising commodity prices, the economy rebounded robustly in the wake of the pandemic and house prices surged. However, labour shortages began to emerge and supply constraints coupled with the rising global energy prices sent inflation to its highest level since the early 1990’s. Monetary policy has tightened significantly, weighing on demand.

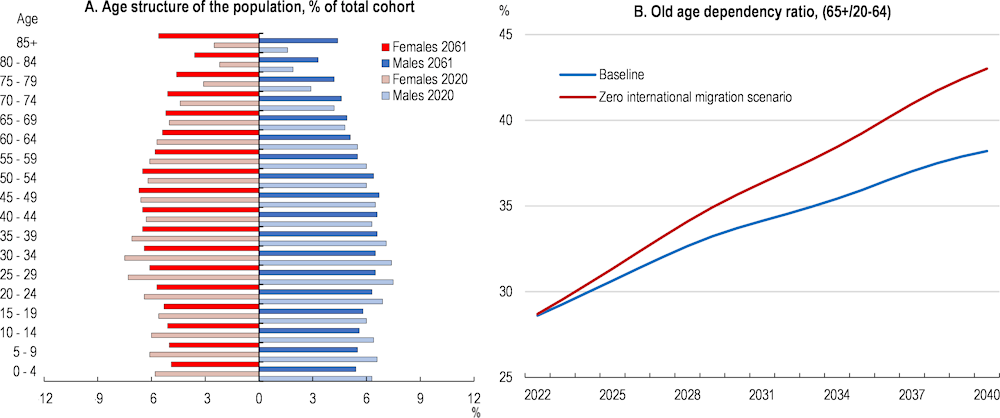

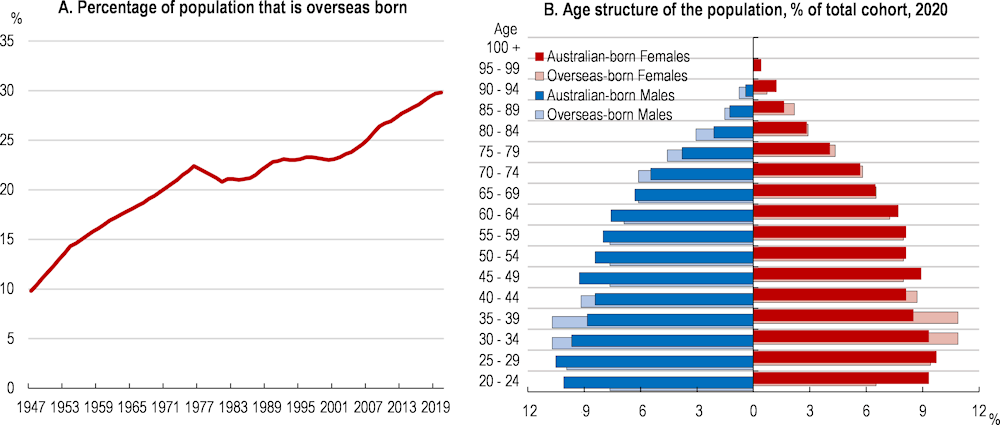

External forces loom large over Australia’s medium-term economic outlook. As an economy that benefits significantly from foreign commodity demand, rising geopolitical tensions and global fragmentation are a risk to national income. The global climate transition will impact the economy, both through the influence on demand for Australian fossil fuel exports and the reshaping of domestic industry in line with net zero commitments. Australia is highly exposed to climate-related hazards, creating challenges for businesses and communities, particularly in certain regions. At the same time, the ageing population will be a headwind to economic growth and lead to structural shifts in the economy over the coming decades.

The economy has the potential to prosper in such an environment. Australia is abundant in the critical minerals needed in a low carbon world and has the natural endowments to generate large amounts of renewable energy. Immigration is a well‑established source of population growth and could lean against the natural decline in the working age population as the economy ages. There is scope for better integrating women in employment and further embracing the digital transformation that can work in the same direction. Calibrating public policies to promote an adaptable economy that manages the ongoing transitions will be key to realise this economic potential.

The government has focused on reforms to promote stronger and more inclusive economic growth. Two of the key priorities have been ensuring an effective climate transition and improving gender equality. Australia is committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050 and more ambitious medium-term emission reduction and renewable energy targets have been announced. In promoting greater gender equality, significant reforms have already been undertaken to expand paid parental leave, improve access to childcare and roll-out gender responsive budgeting. A host of policy reviews have also been established to support this agenda.

Against this background, the three key messages from this Economic Survey are:

Inflation remains high and fiscal pressures are on the horizon due to population ageing and climate change. Monetary policy should remain restrictive until underlying inflation is clearly on track to meet the central bank target. Fiscal buffers need to be rebuilt, including by better managing fluctuating revenues due to commodity-price cycles.

Gender inequalities have steadily declined but remain visible in the labour market. However, reforms to tax, childcare, education, social benefits and parental leave can improve labour market opportunities for women, promote more equal sharing of unpaid work between genders and help more vulnerable women, notably single mothers.

The climate transition is underway, but further policy measures are needed to meet emissions goals, support the reallocation of workers and adapt to climate change. The Safeguard Mechanism should be further strengthened if it does not deliver the expected emissions reductions. Given the abundance of renewable energy resources and a large wealth of critical minerals, Australia can secure the energy transition while remaining a key player in international energy markets.

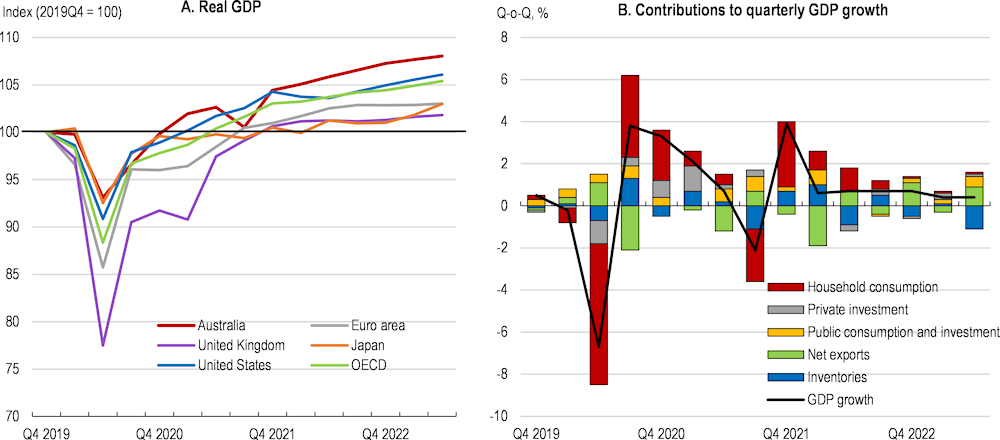

Economic growth is slowing

The pace of economic growth in Australia continues to slow, following a more rapid recovery from pandemic lockdowns than in other major economies (Figure 1.1). Real household consumption growth has weakened after a strong pickup as the economy reopened from the Delta-variant lockdowns in late 2021. Private investment has fallen as supply constraints, higher interest rates and falling house prices have led to a decline in housing investment, although private business investment has remained relatively resilient. Quarterly growth is projected to remain weak in 2023 as financial conditions continue to tighten and the rising cost of living affects household spending decisions, before picking up slightly through 2024 as growth slowly returns towards trend.

Figure 1.1. The economy recovered rapidly, but growth is now slowing

Inflation remains elevated and monetary policy has tightened in response

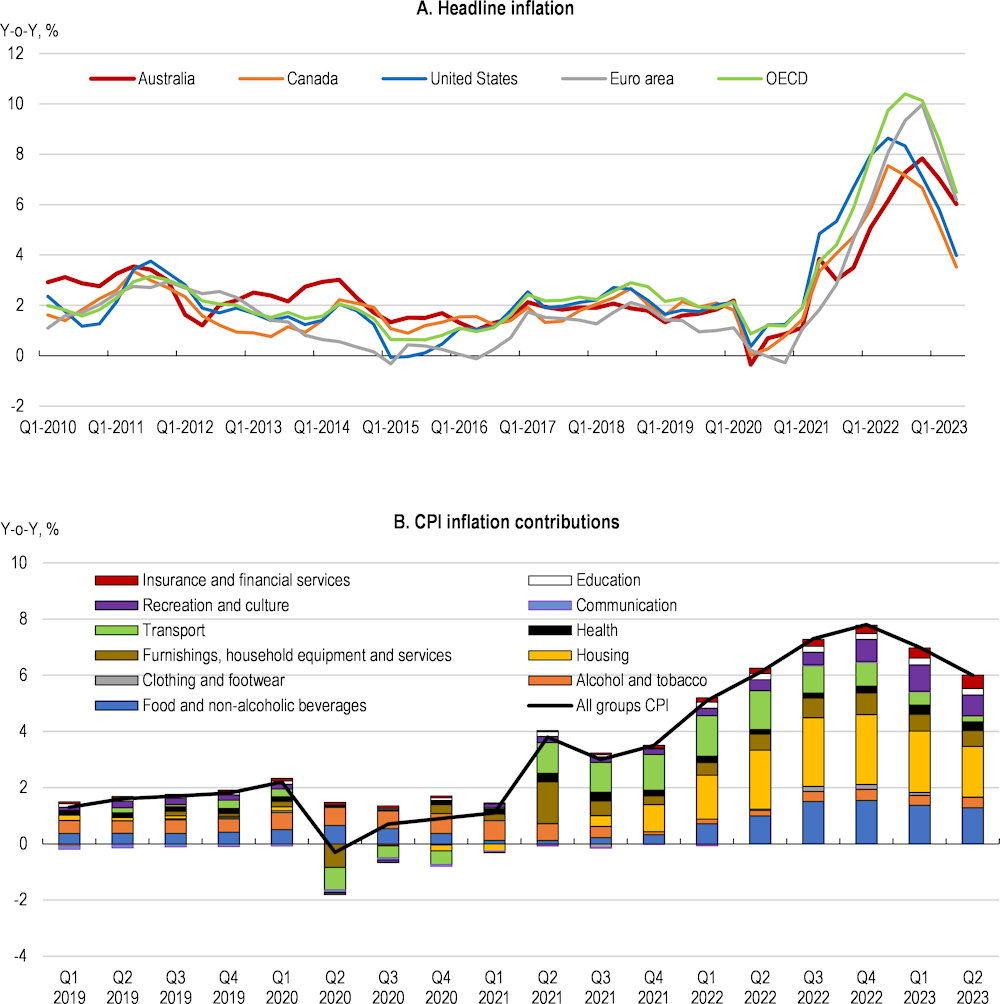

Inflation rose rapidly following the end of pandemic restrictions amid a surge in global commodity prices that contributed to higher domestic energy prices for consumers. It has begun to fall, but remained rapid at an annual rate of 6% in the second quarter of 2023 (Figure 1.2, Panel A). Inflationary pressures progressively broadened from manufactured goods, food and energy inflation, driven by strong demand accompanied by global supply chain bottlenecks, to services inflation. The housing component rose particularly strongly, with a sharp increase in new dwelling prices following the most acute phase of the pandemic and, more recently, rising rents (Figure 1.2, Panel B). Strong demand for travel during 2022 put upward pressure on hospitality and accommodation prices, in part also due to higher fuel prices that caused airfares to surge. Measures of underlying inflation remain elevated, with trimmed mean inflation of 5.9% in Q2 2023. The Commonwealth Government’s Energy Price Relief Plan, announced in December 2022 and which set a cap on wholesale coal and gas prices and provided targeted energy bill relief, is expected to reduce headline inflation by ¾ of a percentage point by the June quarter of 2024. Until recently, Australia has only published a quarterly CPI series, unlike most other OECD countries which publish a monthly series. However, an experimental monthly series began being published in November 2022. While this is a welcome development, the series is based on incomplete data given that some prices are only collected quarterly. The monthly CPI indicator should be further developed to bring Australia in line with data dissemination standards in other OECD economies.

Figure 1.2. Inflation has peaked but remains high

Short-term inflation expectations have decreased in recent quarters but remain above the RBA’s 2-3% target band. Union officials, who participate in minimum and award wage deliberations and the negotiation of enterprise bargaining agreements, currently expect inflation of 4.3% one year ahead and 3.4% two years ahead. Longer-term inflation expectations from financial markets, such as the break-even 10-year inflation rate, remain consistent with the RBA target.

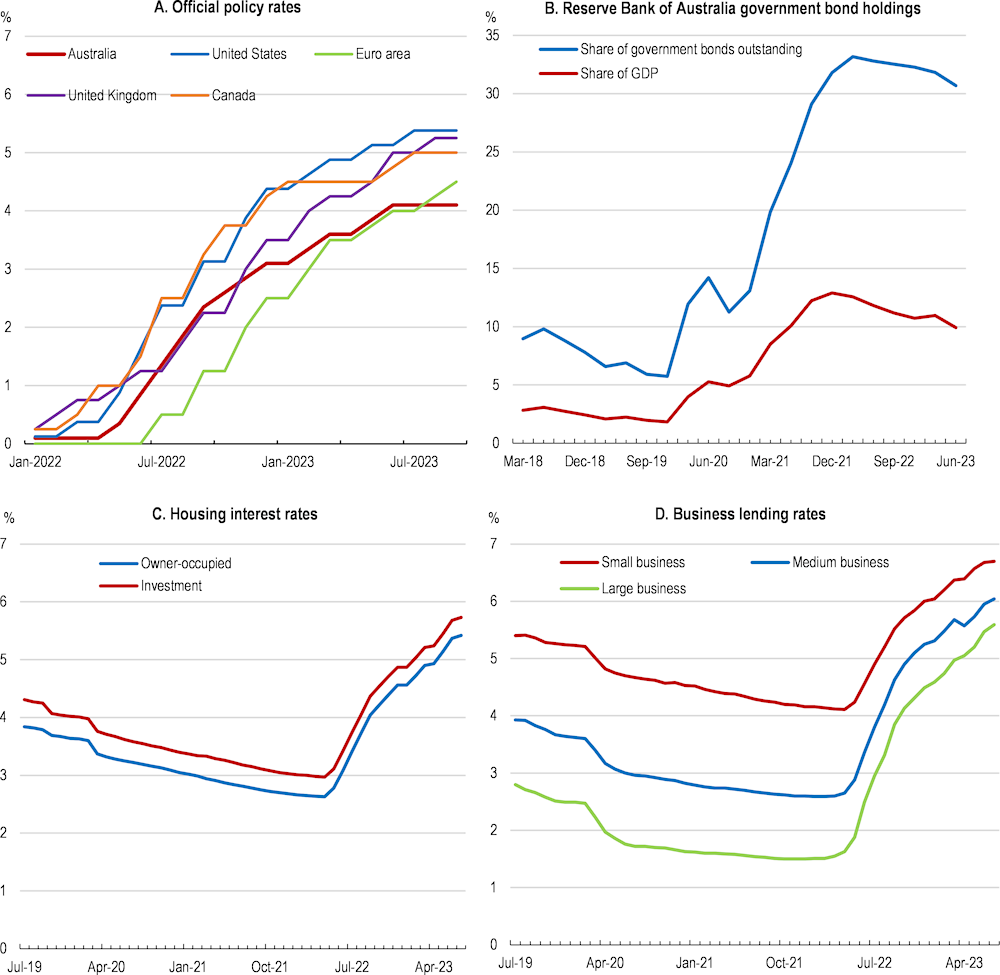

The Reserve Bank of Australia Board has significantly tightened monetary policy settings in response to the surge in inflation. The overnight cash rate has been lifted by a cumulative 4 percentage points since May 2022 (Figure 1.3, Panel A) and Central bank holdings of government bonds have been gradually maturing since mid-2022 (Figure 1.3, Panel B). The Term Funding Facility, established during the pandemic to provide low-cost fixed-rate funding to domestic banks, has begun to mature and is set to fully unwind by mid-2024. Market interest rates have risen sharply in response to this set of measures (Figure 1.3, Panel C and D), with a high share of the outstanding loan stock on variable interest rates.

Figure 1.3. Monetary policy has tightened significantly

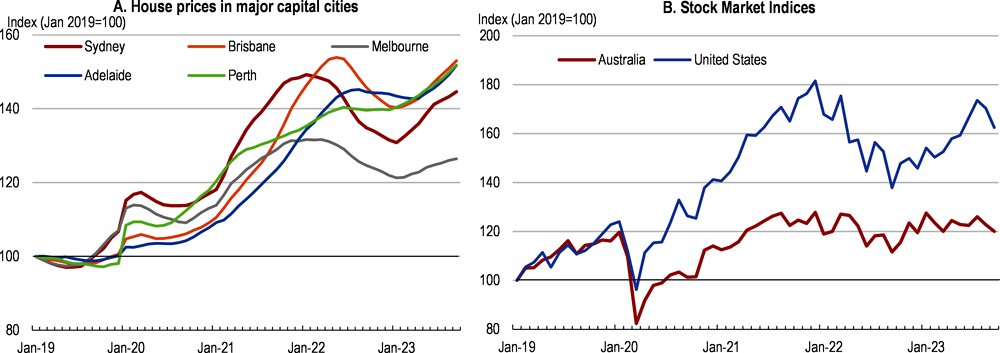

There have been some impacts of monetary policy tightening on asset prices, though declines have so far been orderly. House prices began to fall in early-to-mid-2022 but have stabilised since early 2023 (Figure 1.4, Panel A). The largest peak to trough falls were in Sydney (-13.8%), Brisbane (-11%) and Melbourne (-9.6%), with Perth and Adelaide experiencing only small price declines. As in other OECD countries, the commercial property market has weakened owing to both cyclical conditions and structural shifts such as increased working from home and online retail shopping. Vacancy rates for offices in central business districts are at the highest levels since the 1990s and falling rents have contributed to valuations around 10% lower in the office market and 8% lower for retail and industrial property (Lim et. al., 2023). The Australian stock market has tracked broadly sideways since mid-2021 (Figure 1.4, Panel B). The rise in equity prices from the pandemic trough was less marked than in some overseas equity markets, such as the United States, partly reflecting a smaller IT sector in the Australian market.

Figure 1.4. Declines in asset prices have been orderly

Note: In Panel B, the stock market index for Australia is the S&P/ASX200 and for the United States it is the S&P500 Composite Index.

Source: Corelogic, Standard & Poors, Refinitiv.

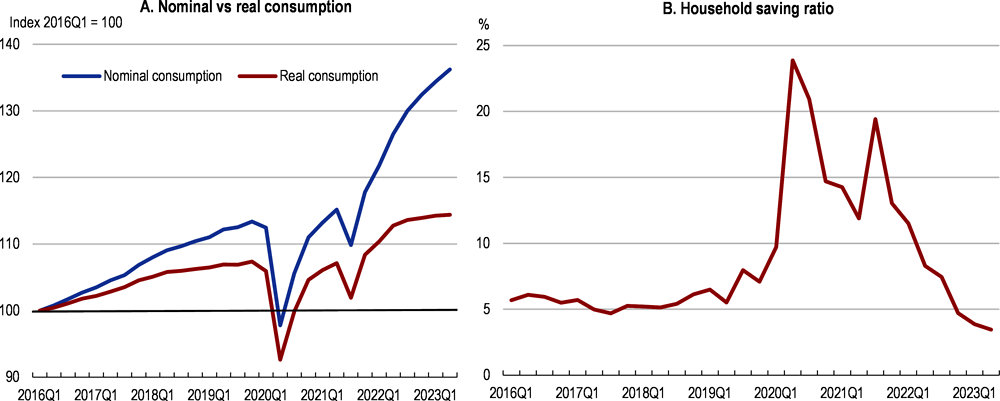

While real consumer spending growth has slowed amid rising inflation and tightening financial conditions, nominal consumption has been significantly above trend, supported by a sharp reduction in the household saving ratio and government support measures (Figure 1.5). While the saving ratio is now below pre-pandemic levels, the savings accumulated since 2020 will continue to support consumption, although there is evidence that it is concentrated among wealthier households with a lower propensity to consume. Consumer spending patterns have gradually rebalanced back from goods towards services, and from essential towards discretionary spending since the pandemic, with strong consumption of transport, hotels, cafes and restaurants, and recreation and culture.

Figure 1.5. Nominal consumption has remained strong

Exports have supported the economy

Exports rose for the fifth consecutive quarter in Q2 2023 with the continued return of international students and tourists to Australia in the wake of the pandemic. Rural exports have also risen strongly over this period, partly driven by record wheat crops due to favourable growing conditions over recent years and the elevated prices that resulted from dry conditions in other wheat exporting countries and Russia’s war against Ukraine. Aside from its impact on global commodity prices and domestic inflation, the direct trade implications for Australia of the war and subsequent sanctions on Russia have been limited. Australian exports to Russia and Ukraine have historically been small, with combined two-way trade amounting to just 0.2% of Australia’s global trade in 2020.

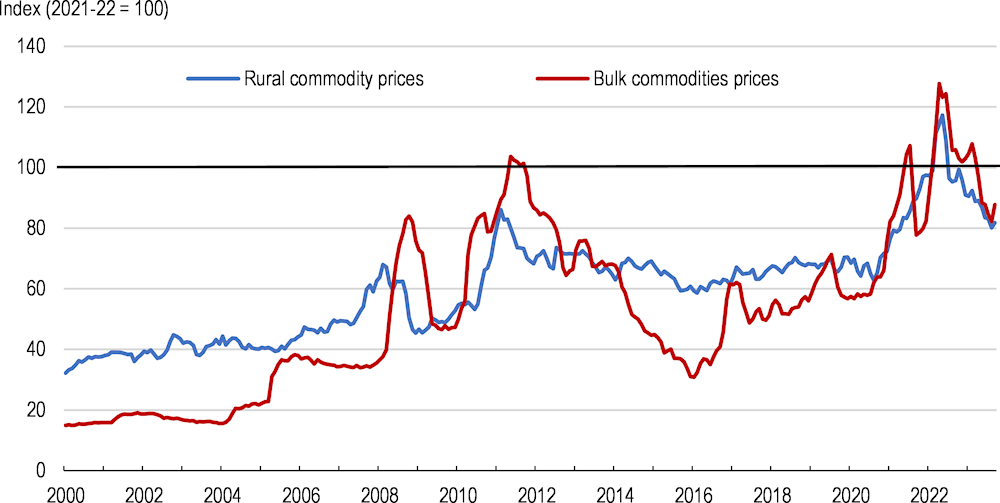

Australian commodity export prices remain historically elevated (Figure 1.6). Bulk commodity prices soared by 55% between December 2021 and April 2022, their most recent peak, and have since returned to close to December 2021 levels. Rural commodity prices have also eased in recent months and are now 16% below December 2021 levels. The trade surplus strongly increased during the first half of 2022 as the terms of trade improved but has since moderated with lower commodity prices and Australians increasingly travelling abroad. Notably, the sharp rise in bulk commodity prices since the pandemic has not led to a boom in investment in the mining sector, in part due to concerns about viability in the context of tightening of emissions standards globally.

Figure 1.6. Commodity prices have fallen following a surge due to the war in Ukraine

Australian commodity export prices, Index (2021-22=100)

Note: Rural commodities include wool, beef, wheat, barley, canola, sugar, cotton and lamb. Bulk commodities include iron ore, metallurgical coal and thermal coal. The indices are shown in terms of Special Drawing Rights (SDR), which are less affected by exchange rate movements.

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia.

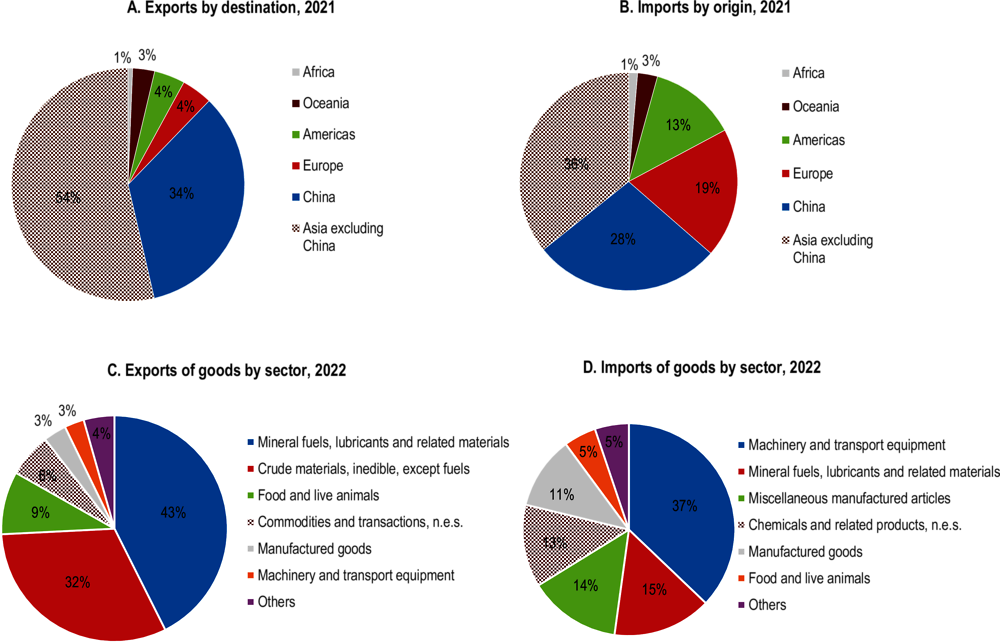

The Asia-Pacific region continues to be critical for Australian trade, accounting for almost 90% of total exports (see Figure 1.7). China is Australia's largest two-way trading partner in goods and services and remains the major export market, with iron ore accounting for 60% of bilateral exports. Over the past two decades, the share of Australia’s merchandise exports destined for China has increased from 10% to around 40% and now surpasses Australia’s total merchandise exports to all OECD countries combined. Trade in Value Added indicators suggest that a relatively small share of Australian exports to China are used as intermediaries in Chinese exports: China was the final destination for 94% of Australia’s gross exports to the country in 2018. Looking ahead, Australia’s dependence on China may fall as export opportunities in other countries in the region and in India develop.

Figure 1.7. Asia-Pacific is the core bilateral trading region

Note: Data are for 2021. In Panel C, Others include crude materials, beverages and tobacco, animal and vegetable oils, and commodities and transactions. In Panel D, Others include insurance and pension, construction services, and other services.

Source: OECD International Trade by Commodity Statistics database.

In recent years, China placed import restrictions on certain Australian commodities, including coal, barley, wine, beef and cotton. For some of these products, exporters have been successful at pivoting to other markets. For instance, coal exports to India, Brazil and Indonesia picked up notably. China started removing these restrictions on imports from Australia during the first months of 2023. The trade tensions have highlighted Australia’s reliance on China as an export market. Australia has recently increased efforts to diversify its exports, notably through the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement, which entered into force in late 2022. Between 2021 and 2022, exports to India, Korea and Japan grew by 42%, 43% and 84% respectively (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). The value of Australian exports to India are currently about 20% of those sent to China. Two thirds of bilateral exports to India are coal, with very little iron ore exported so far, partly due to India’s strong domestic reserves. Australia’s vast endowments of minerals critical for the climate transition, such as lithium, provide further opportunities for diversification. Lithium exports have soared in recent years, rising more than tenfold between 2021 and 2022, although the vast majority has been destined for China, which is the largest global investor in clean energy technologies and the world’s main processor of lithium.

The labour market is tight despite rising labour supply

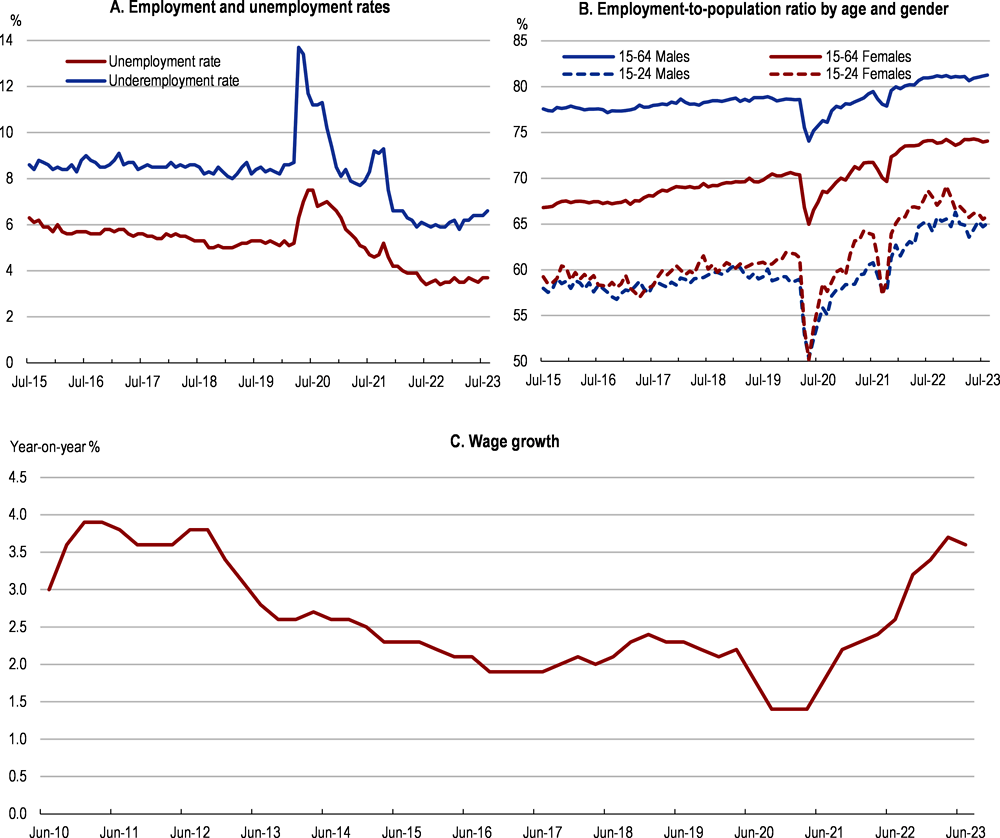

Labour demand has remained strong, despite slowing growth. The unemployment rate has hovered around 3½% since mid-2022, near a 50-year low, and the underemployment rate, which accounts for workers willing to work additional hours, is near its lowest point since 2008 as businesses have increased the hours of existing staff (see Figure 1.8, Panel A). Strong labour demand has drawn more people into the labour force, particularly women and young workers. Employment-to-population ratios are near record highs across most cohorts (Figure 1.8, Panel B). Labour supply has also been supported by strong growth in overseas immigration since Australia’s borders reopened, which notably allowed overseas students and working holiday makers to return. While these increases in labour supply have provided some relief, the labour market remains tight, and reports of labour shortages remain. The number of job vacancies have eased, but remain almost double the level reported at the onset of the pandemic according to the Job Vacancies Survey by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. One in three small-and-medium enterprises continue to identify labour shortages as a “very significant” issue, with the most affected sectors being construction, manufacturing, transport and storage and retail (NAB, 2023).

Figure 1.8. Strong labour demand has led to a tight labour market

Note: Underemployed workers are employed people who would prefer, and are available for, more hours of work than they currently have. The underemployment rate is defined as a proportion of the labour force.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Nominal wage growth has picked up due to the tight labour market and rising inflation, increasing to 3.6% year-on-year in Q2 2023 (Figure 1.8, Panel C). Employee earnings have risen across the income distribution, but growth has been strongest for lower-paid groups. Wage growth will be supported by the decisions of the Fair Work Commission on the minimum wage, which rose by 8.6% in July, and award wage rates (which set out minimum pay conditions for particular industries and occupations), which rose by 5.75%. However, the minimum wage only applies to 0.7% of all employees and modern award-reliant employees account for only 11% of the wages bill. There are signs that wages under recently negotiated Enterprise Bargaining Agreements also continue to drift up. Such agreements cover around one third of Australian enterprise employees. Nonetheless, wage growth has not kept pace with inflation, and, while it has partly contributed to services inflation, the risk of a wage-price spiral appears contained.

Economic growth will remain slow before recovering

Quarterly economic growth is projected to slow further in 2023, before picking up gradually in 2024 and moving back to around trend growth by the second half of 2025 (Table 1.1). Higher interest rates and cost of living pressures will dampen spending by households with fewer accumulated savings and weigh on housing investment. Continued strong population growth and higher exports as travel further recovers will partly offset these headwinds. As GDP growth slows, the unemployment rate is projected to start rising, reaching 4.4% in 2025. Inflation will moderate, aided by abating global inflationary pressures particularly for goods, and is expected to fall to the top of the RBA target band by the end of 2024. There are both upside and downside risks to economic growth. A quicker than expected fall in inflation, which could arise if goods prices normalise to a greater extent than currently projected, could require less restrictive monetary policy. However, further declines in house prices and persistent inflation could cause households to cut back on spending more than expected. A sharper than expected slowdown in China poses an additional downside risk and could have a significant impact on exports and GDP growth.

Table 1.1. Growth and inflation are projected to ease

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices AUD Billion |

Percentage changes, volume (2020/2021 prices) |

|||||

|

GDP at market prices |

1 972.9 |

5.2 |

3.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

|

Private consumption |

1 011.5 |

5.1 |

6.4 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

|

Government consumption |

450.2 |

5.4 |

5.3 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

442.1 |

10.6 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

|

Final domestic demand |

1 903.8 |

6.4 |

4.9 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

|

Stockbuilding 1 |

-2.6 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

1 901.1 |

7.1 |

5.2 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

436.4 |

-2.1 |

3.4 |

9.2 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

364.7 |

5.6 |

12.8 |

4.2 |

3.0 |

3.3 |

|

Net exports 1 |

71.8 |

-1.5 |

-1.5 |

1.6 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Memorandum items |

||||||

|

GDP deflator |

_ |

5.5 |

7.9 |

3.6 |

3.0 |

2.7 |

|

Consumer price index |

_ |

2.8 |

6.6 |

5.5 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

|

Core inflation index 2 |

_ |

2.4 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

_ |

5.1 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

-1.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

-0.6 |

-0.7 |

|

|

Household saving ratio net (% of disposables income) |

_ |

14.7 |

8.0 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

5.1 |

|

General government net lending (% of GDP) |

_ |

-4.8 |

-1.8 |

-1.1 |

-1.7 |

-1.5 |

|

Underlying general government net lending (% of potential GDP) |

-4.0 |

-2.0 |

-1.2 |

-1.4 |

-1.1 |

|

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

_ |

64.1 |

56.8 |

57.8 |

59.3 |

60.6 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

_ |

3.0 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

1. Contributions to changes in real GDP, actual amount in the first column.

2. Consumer price index excluding food and energy

Source: OECD.

Table 1.2. Events that could entail major changes to the outlook

|

Shock |

Likely impact |

Policy response options |

|---|---|---|

|

A period of deglobalisation coupled with a rise in protectionism. |

A reduction in global trade would have a significant effect on Australia as a small open economy. Export-oriented sectors such as resources and agriculture could be particularly impacted. Protectionist measures could affect Australian supply chains, impair access to critical goods and raise import prices. Productivity and technology adoption could also be impacted. |

Monitor risks to supply chains and improve their resilience by increasing diversification. Improve collaboration with crucial trade partners and international bodies such as the WTO. |

|

A wage-price spiral leading to persistently high inflation. |

High economic uncertainty, significant relative price distortions, de-anchoring of inflation expectations, loss of international competitiveness, and a possible economic downturn. |

A greater degree of monetary policy tightening. |

|

A significant decline in commodity prices, perhaps due to a structural decline in fossil fuel demand in major export markets in response to energy security considerations or changes in climate policy. |

A substantial fall in demand for Australian commodities would have a large impact for the mining and agriculture sectors and related industries. |

Provide support to affected workers and regions. Promote further diversification and the development of other export markets such as critical minerals including lithium, which will be crucial for the climate transition. |

|

Severe climate-related disasters. |

More frequent adverse climate events such as heat waves, forest fires or floods would materially lower economic activity and would have significant costs in terms of property damage, health, wellbeing of the population, and fiscal costs. The agricultural sector is especially vulnerable. A higher frequency of such events could also lead to a lack of access to insurance in certain areas. |

Improve the resilience of infrastructure to climate and natural hazards and ensure that there are mechanisms for a coordinated policy response across different levels of government. Provide targeted fiscal support to affected areas. Improve climate data collection and forecasting of climate hazards and ensure that the information is widely disseminated. |

Monetary policy should remain restrictive

Monetary policy must continue to navigate a difficult path, ensuring that underlying inflationary pressures do not become embedded while closely monitoring the impact of the past rapid and globally synchronised monetary policy tightening on the real economy. If services inflation remains surprisingly persistent, long-run inflation expectations risk becoming de-anchored. At the same time, further tightening of financial conditions will occur as pandemic-era fixed rate loans further expire and the Term Funding Facility and central bank government bond holdings mature. Weighing the uncertainties, a restrictive stance of monetary policy remains appropriate until there are clear signs that underlying inflationary pressures have abated. Indeed, further monetary policy tightening may be necessary if upside risks to inflation emerge. Considerable uncertainty calls for a data dependent approach coupled by clear communication of the monetary policy reaction function.

Changes to the monetary policy framework are being implemented, following an independent review of the Reserve Bank of Australia in 2023 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023a) that was recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey of Australia (Table 1.3). The government has accepted in principle the recommendations, including the establishment of separate boards related to monetary policy decisions and the governance of the institution. It is anticipated that the monetary policy Board will comprise individuals with expertise in relevant economic fields appointed through a transparent and skills-based process. This differs from the current arrangements whereby the Board predominantly includes highly‑qualified private sector leaders. The review also recommended further enhancing communication about monetary policy, including through regular press conferences and external Board members being required to publicly explain monetary policy decisions.

The RBA has been actively reflecting on the efficacy of the policy tools adopted during the pandemic. In 2022, it published reviews of its pandemic-period bond purchase programme (RBA, 2022a), the target for the yield on the three-year Australian Government bond (RBA, 2022b) and its approach to forward guidance (RBA, 2022c). These detailed assessments can benefit other central banks in their future policy considerations.

The reviews found all three measures to be successful in lowering funding costs and supporting the provision of credit to the economy. However, while the design and implementation of the bond purchase programme was found to have worked broadly as intended, this was not the case for the other two policies considered. The exit from the yield curve target in 2021 was disorderly for bond markets, as improving economic conditions led to market yields being pushed above the target. The review found that the decision-making process in implementing the policy was particularly focused on limiting bad outcomes and a greater focus on potential upside scenarios could have helped avoid the disorderly exit. On forward guidance, while a time-based element to the communication reinforced the yield curve target through emphasising that the Board did not expect to lift the cash rate until 2024, the cash rate was eventually increased much earlier. This caused the RBA to attract significant criticism and may have impacted credibility. The review concluded that future forward guidance should tend to be qualitative in nature, flexible and conditionality focused on the Board’s policy objectives of inflation and unemployment. Nonetheless, neither the introduction of a yield target or a strong form of forward guidance was ruled out for the future. Looking forward, the RBA should consider maintaining a regularly updated framework for the use of unconventional monetary policy tools in case the cash rate is at the zero lower bound.

Table 1.3. Past OECD recommendations on monetary and financial policy

|

Recommendations in previous Survey |

Action taken since September 2021 |

|---|---|

|

As in other OECD countries, undertake a review into the monetary policy framework that is broad in scope, transparent and involves consultation with a wide variety of relevant stakeholders. |

The government enacted an independent review of the Reserve Bank of Australia in 2022. The final report was published on 20 April 2023. The review was very broad in scope, transparent and involved consultation with a wide variety of relevant stakeholders. |

|

Overhaul the Personal Property Securities Register then increase awareness among small businesses and lenders. |

In September 2023, the Government announced its response to the 2015 statutory review of the Personal Property Securities Act 2009. The response accepted 345 of the review’s 394 recommendations and included draft legislation designed to streamline the process of using personal property to secure credit. |

|

Extend open banking to facilitate switching of providers and other actions (“write access”) with appropriate protections. |

The federal government introduced legislation into Parliament in November 2022 to expand the Consumer Data Right to enable action initiation (or ‘write access’). Further policy development is being undertaken by Treasury to identify the priority actions to bring into the Consumer Data Right and the key considerations for rules and standards to implement action initiation. |

|

Create a roadmap for improving the consistency, comparability and quality of reporting of climate-related risks by listed companies and financial institutions. |

The federal government has committed to introducing standardised, internationally-aligned reporting requirements for large businesses and financial institutions to make climate-related disclosures regarding governance, strategy, risk management, targets and metrics – including greenhouse gasses. Federal Treasury released its second consultation paper in June 2023 which proposes a broad range of companies and financial institutions be subject to mandatory disclosure requirements. This would commence with the largest listed and unlisted companies for the 2024-25 financial reporting periods, with other companies phased in over time. |

|

Complete the implementation of the reforms arising from the Royal Commission into the financial sector |

51 of the Royal Commission’s 54 recommendations to government have now been implemented following passage of the Financial Accountability Regime in March 2023. The remaining three (concerning mortgage brokers and point-of-sale credit) have been overtaken by events. |

Financial pressures are increasing but the banking system appears well-prepared

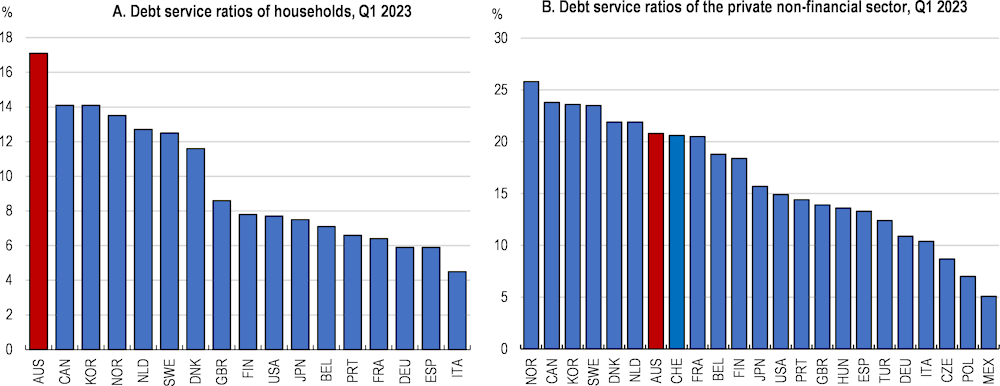

On aggregate, households balance sheets so far remain in good shape. While the decline in housing prices in 2022 and early 2023 impacted household wealth for some segments, housing prices in most states remain well above their pre-pandemic level and mortgage arrears are low. Nonetheless, household debt servicing costs are elevated by international standards (Figure 1.9, Panel A), reflecting high household debt levels and the large share of variable rate mortgages. Debt servicing costs are especially high for those in low‑income cohorts: around 45% of low-income people with a mortgage were devoting greater than one-third of their income to servicing their housing loan in early 2023 (RBA, 2023b). Some households have experienced a sharp increase in debt servicing costs since 2022 owing to their low fixed rate housing loans resetting onto variable rates, with an estimated 20% of fixed rate mortgage holders set to make this transition in 2024. Even so, many borrowers hold substantial amounts of liquid assets, including mortgage prepayments, and so are well placed to navigate a period of tighter financial conditions. Household debt is also mostly held by higher income households: Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey data highlight that around 60% of the stock of household debt was held by households in the top two equivalised income quintiles in 2021, with only 4% held by those in the lowest quintile. The strong job market is an important factor continuing to buoy household finances. Scenario analysis by the RBA suggests that, with an increase in unemployment, 40% of indebted households experiencing job loss would be at risk of depleting prepayment buffers within six months, even if they were to substantially reduce non-essential spending (RBA, 2023b).

Figure 1.9. Debt servicing ratios are high by international standards

Note: The debt servicing ratio is defined as the ratio of interest payments plus amortisation to income.

Source: Bank for International Settlements.

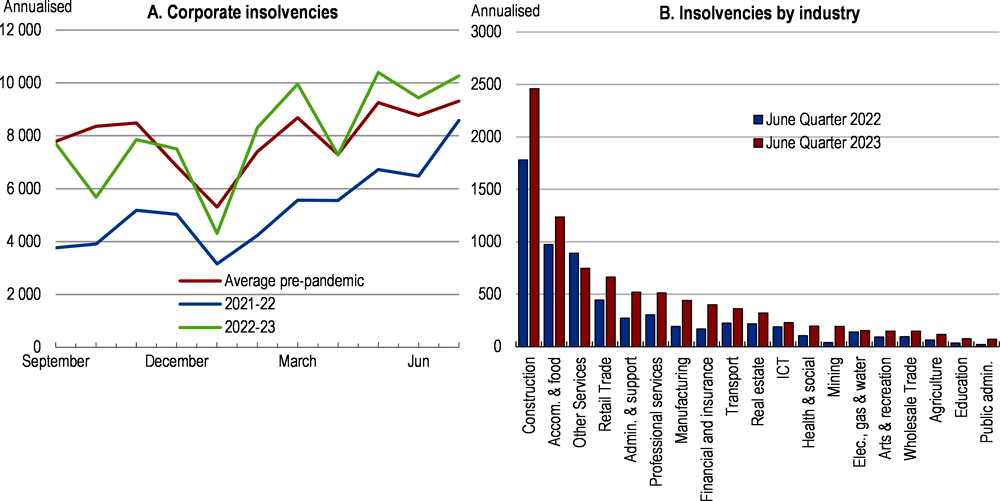

Corporate insolvencies have risen over the past year, but they remain broadly in line with pre-pandemic averages (Figure 1.10, Panel A). The construction sector accounts for around 27% of insolvencies (Figure 1.10, Panel B), reflecting margin pressures for builders tied to fixed-price contracts signed before the marked rise in input and labour costs (RBA, 2023b). The increase in insolvencies in the commercial real estate sector has been limited so far, despite high vacancy rates for office and retail properties and higher borrowing costs for landlords. Bank lending standards for commercial property have been conservative in recent years, with most loans written with loan-to-valuation ratios below 65% and a requirement that borrowers have earnings that cover twice interest expenses (an interest coverage ratio above 2; Lim et. al. 2023).

Figure 1.10. Corporate insolvencies have risen but remain below pre-pandemic levels

Note: Data are for the first time a company enters external administration or has a controller appointed. The pre-pandemic average is for each respective month during 2017-19.

Source: Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

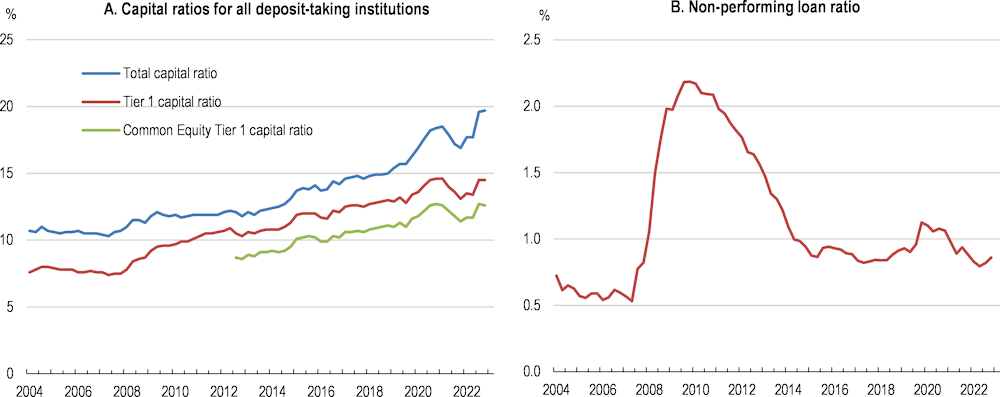

The banking sector remains well-capitalised, with capital ratios having continued to increase well above regulatory requirements through the past year (Figure 1.11, Panel A). The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority introduced a new capital framework in January 2023 that is more closely aligned with Basel III standards. The framework includes a countercyclical capital buffer currently set at 1% and a larger capital conservation buffer for large banks. The non-performing loan ratio remains at historically low levels, despite the signs of increasing household and corporate stress (Figure 1.11, Panel B). Banks are relatively well positioned against interest rate risk, as they are required to carry capital to address the risk of rising interest rates as part of their core capital requirements, incentivising them to hedge residual interest-rate exposures (Lonsdale, 2023). A high share of variable rate loans on bank balance sheets also means that many assets are repriced relatively quickly following a shock to funding costs (RBA, 2023b).

Figure 1.11. The banking sector is well capitalised and non-performing loans are low

In the current environment, there does not appear to be a case for either loosening or tightening macroprudential policies. Risks for bank funding related to the maturity of the Term Funding Facility require careful monitoring by regulatory authorities. The value of bank repayments will increase markedly in the period to 2024 as the facility matures, and while banks are generally ahead in their funding plans (RBA, 2023b) a bout of volatility in global funding markets could push funding costs higher.

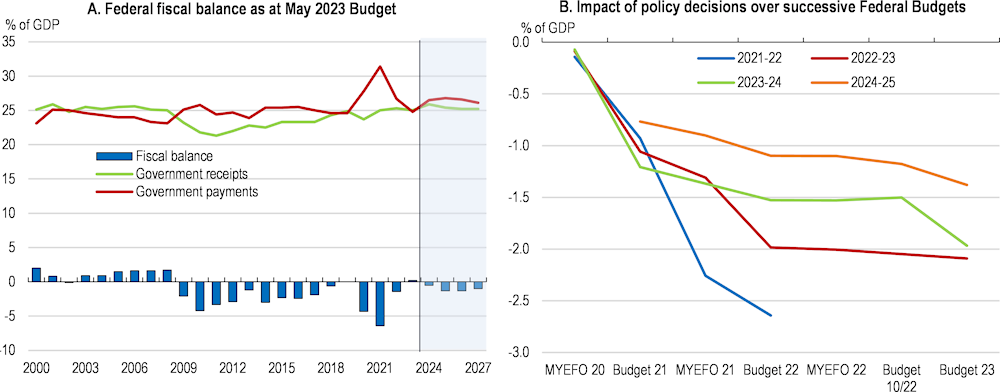

The budget balance has improved, but there are long-term challenges

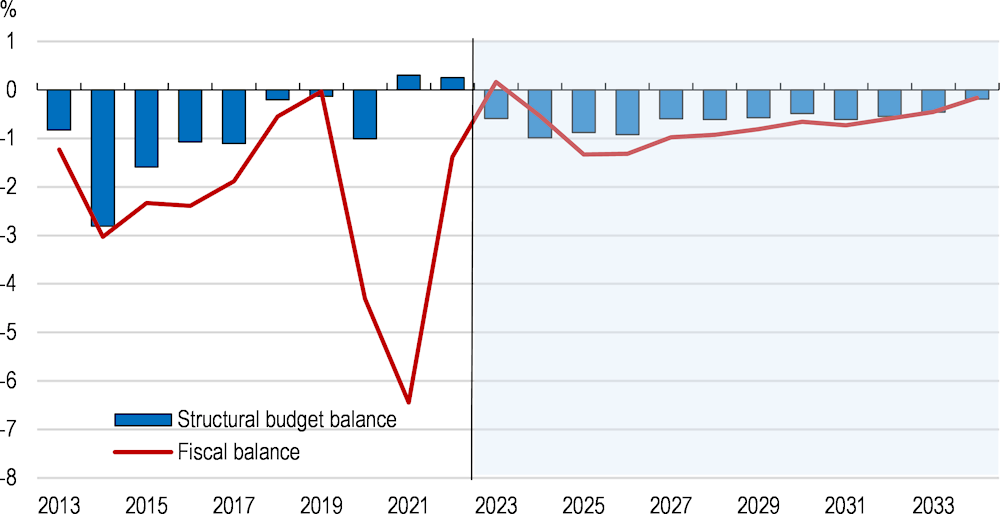

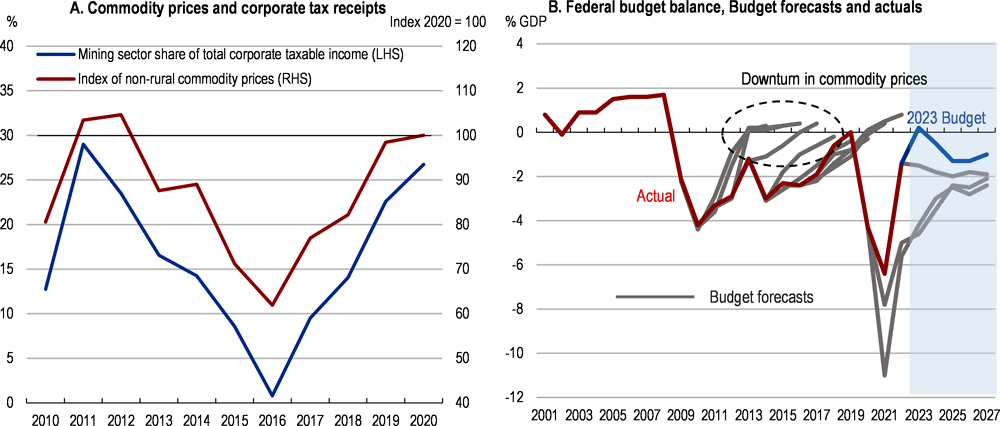

The Federal Budget deficit peaked at -6.4% during the pandemic, as emergency supports were mobilised, but has narrowed as the economy has recovered and commodity prices have risen sharply (Figure 1.12, Panel A). Nonetheless, the federal government expects the deficit to re-emerge over the years ahead, partly due to spending increases introduced over successive recent Budgets (Figure 1.12, Panel B) and strong growth in large expenditure items such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme. The 2023/24 Federal Budget included new permanent spending equivalent to around 0.2% of GDP focused on assisting households, including funding to improve the affordability of primary healthcare, parenting payment changes which will increase benefits for single parents, increased rent assistance and working age payments.

Figure 1.12. The federal fiscal deficit is anticipated to re-emerge in coming years

Note: Panel B shows the cumulated impact of policy decisions for a given fiscal year on the headline fiscal balance. A decline signifies policy decisions in the respective budget that have loosened the fiscal stance.

Source: ABS, Parliamentary Budget Office, Commonwealth of Australia (2023b).

Temporary support to offset higher energy costs was also announced. Energy bill relief is being provided for pensioners, households receiving certain low-income benefits and some small businesses, costing AUD1.5 billion (0.03% of GDP) over 12 months. This measure is temporary, which is appropriate given the uncertainty, and partly targeted given the focus on welfare recipients. However, through taking the form of credits to electricity bills, it distorts price signals and reduces the incentive to lower energy use and switch to more carbon-neutral energy sources.

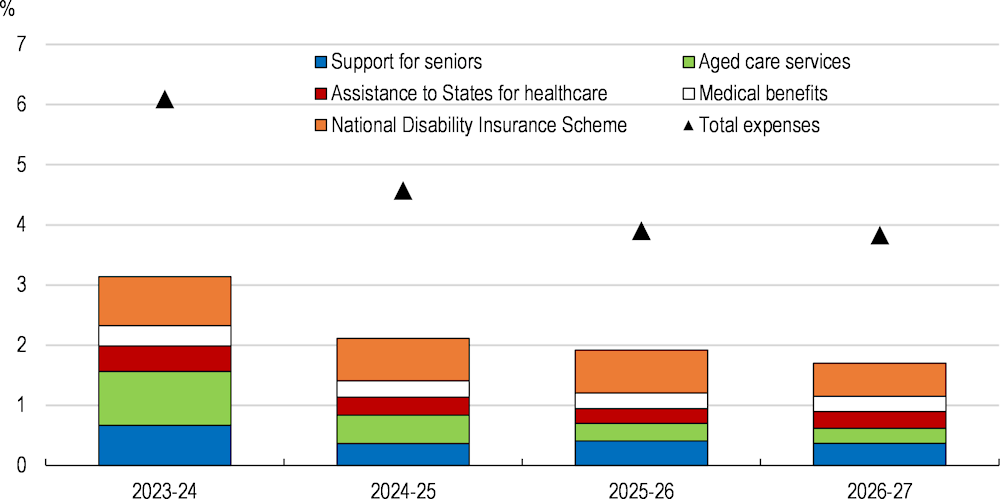

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) applies insurance-based approaches to support those with a permanent and significant disability. It provides uncapped individualised funding determined by the specific needs of participants and has widespread community and political backing. However, the number of people entering the scheme with less complex disabilities has been higher than anticipated, while the rate of scheme exits has been unexpectedly low. The scheme is a large expenditure item, with federal government spending equivalent to 1.6% of GDP in 2023/24, well over the cost of unemployment benefits and childcare subsidies combined (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023b). Although the scheme is co-financed between federal and state governments, all upward variations in costs are funded by the federal government. NDIS expenses are projected to contribute around one sixth of total federal government expenditure growth in the period to 2026-27 (Figure 1.13). However, costs could well be significantly higher. Current Budget projections assume that scheme cost growth declines from 14.4% in 2023-24 to 8% by 2026-27, as a result of National Cabinet agreement on a NDIS Financial Sustainability Framework. Achieving this outcome will require effective implementation of new cost containment measures that are yet to be announced but will be informed by a review of the scheme that is currently being undertaken.

Figure 1.13. The National Disability Insurance Scheme is pushing up federal government spending

Contributions to total federal government expenditure growth, by highest cost programmes

The federal government structural budget deficit, which accounts for the economic cycle, is anticipated to widen to around 1% in 2023/24 (Figure 1.14) giving some support to economic activity. The budget projections assume that commodity prices fall from the currently elevated levels to be more in line with historical norms, contributing to the persistent deficit. Nevertheless, the impact of fluctuations in commodity prices has been somewhat mitigated in recent years by the government saving the majority of revenue upgrades, in line with the current fiscal strategy (Box 1.1).

Figure 1.14. The federal government structural budget balance is anticipated to widen in the short-term

Federal government fiscal balance, % of GDP

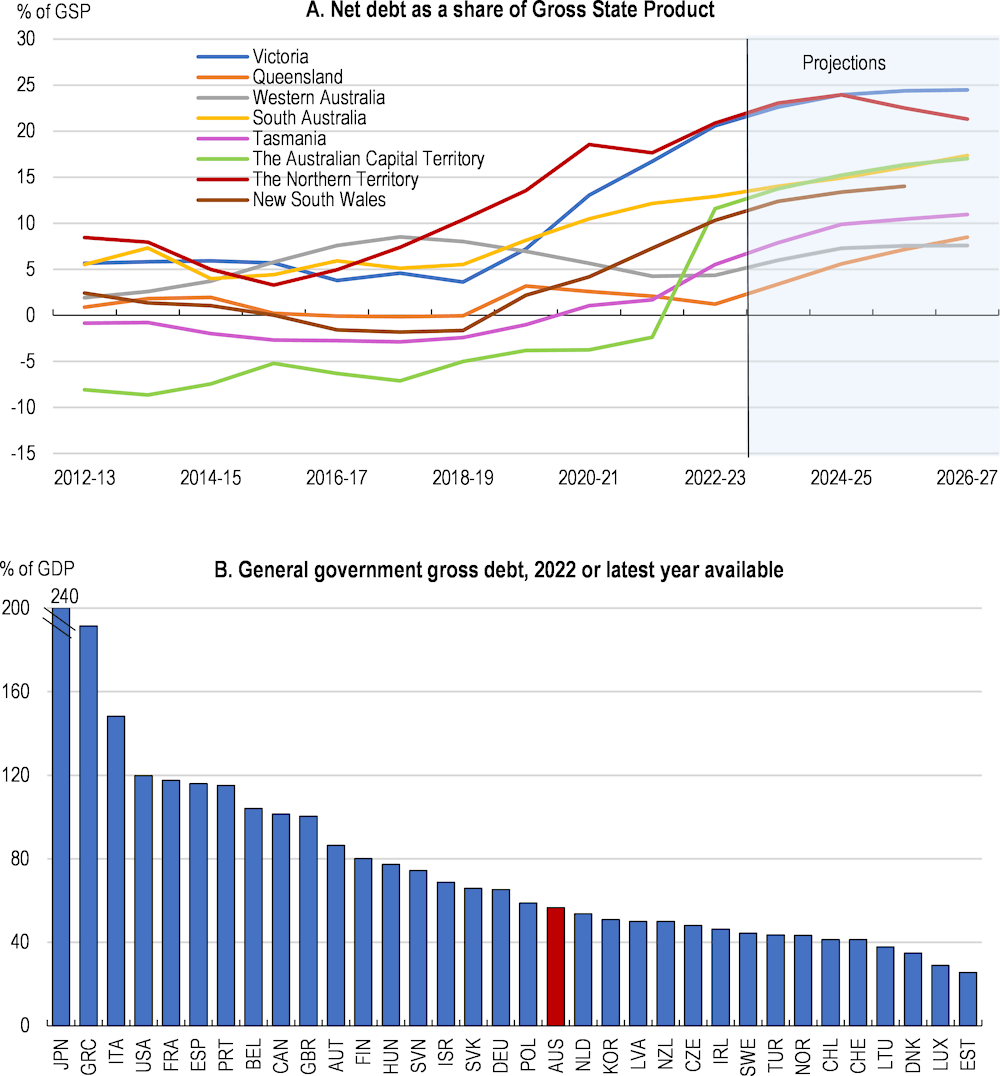

Subnational governments are also running fiscal deficits in aggregate terms. In the year to March 2023, net borrowing by state and local governments was equivalent to 1.7% of national GDP. There are differences across regions. While the largest states of Victoria and New South Wales are both reporting fiscal deficits, high commodity prices are buoying the finances of the states with large mining sectors such as Queensland and Western Australia. As a result of government spending during the pandemic, and significant capital works programmes in some cases, public debt of several states has risen from very low levels (Figure 1.15, Panel A). For example, net debt as a share of gross state product in Victoria has risen from 3.6% in 2018-19 to 22.6% in 2023-24.

Consolidating across levels of government, gross general government debt to GDP is now around 57% (Figure 1.15, Panel B). However, partly due to the prefunding of public pension obligations, net public debt to GDP is 35.9% (IMF, 2023). While at similar levels to many other OECD countries, such as the Netherlands, the past decade saw a larger rise in Australia’s gross public debt to GDP ratio than in most other OECD countries, despite comparatively strong nominal GDP growth. With ageing-related fiscal costs on the horizon and ongoing inflationary pressures in the economy, some fiscal tightening is warranted by unwinding temporary measures and narrowing the structural deficit. In the short term, such an approach would ensure fiscal policy is working in the same direction as monetary policy. Continuing to save windfalls from high commodity export earnings would contribute and help guard against Australia’s longstanding vulnerability to excessive fiscal expansion during commodity booms, as discussed in past Economic Surveys (OECD, 2017a).

Figure 1.15. Public debt has risen in some states

Longer-term fiscal pressures are significant

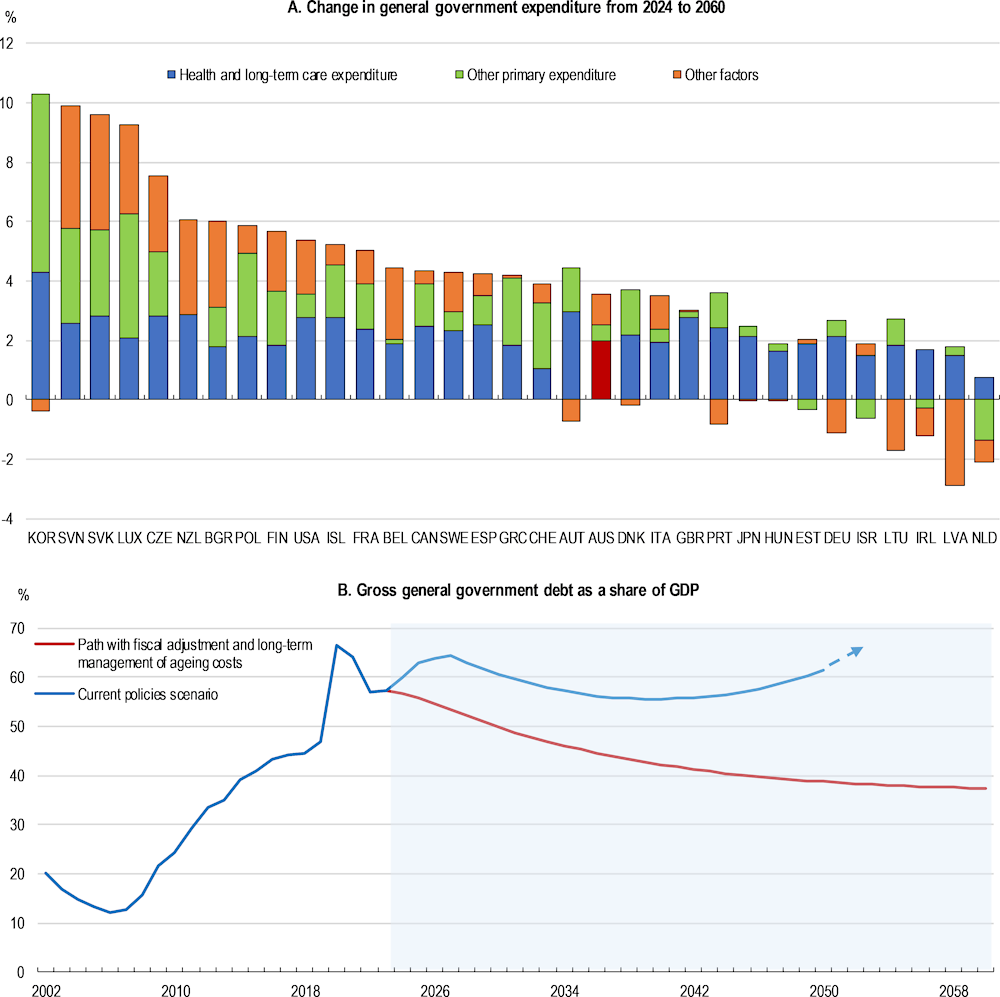

The OECD Long-term Model estimates that fiscal costs related to health and long-term care will increase in Australia as the population ages, rising by 0.8% of GDP by 2040 (Figure 1.16). This implies that a similar reduction of spending or increase in revenue (or combination thereof) will be needed to stabilise the gross debt-to-GDP ratio from the mid-2030s. Without such measures, simulations based on the OECD Long-term Model highlight that the debt to GDP ratio will begin to rise rapidly (Figure 1.16, Panel B).

Figure 1.16. Fiscal costs will rise as the population ages

Note: In Panel A, “Other primary expenditure” is projected based on the assumption that governments will seek to provide a constant level of public spending per capita in real terms. Under some reasonable assumptions, the evolution of this expenditure category relative to GDP becomes an inverse function of the projected evolution of the employment-to-population ratio, as expenditure (numerator) follows population whereas GDP (denominator) follows employment. The “other factors” component captures anything that affects debt dynamics other than the explicit expenditure components (it mostly reflects the correction of any disequilibrium between the initial structural primary balance and the one that would stabilise the debt ratio). Pension expenditure is not included in the figure for any country because the model does not adequately capture the impact of Australia’s superannuation system on public pension costs. In Panel B, the “Persistent consolidation path scenario” assumes that the primary budget balance rises to 0.3% of GDP by 2028 and then stays at that level with ageing costs fully offset by higher taxes or reductions in other spending items. The “Not offsetting ageing costs scenario” takes federal and state government fiscal projections in the period to 2027. Thereafter, the cumulative impact of healthcare costs and other primary expenditure estimated from the OECD Long-Term Model is added to the primary budget balance assumed under the persistent consolidation path.

Source: OECD Long-Term Model, OECD calculations.

Climate change and achieving the climate transition will also bring significant additional fiscal costs that are not factored into current plans and are not fully known. As highlighted in Chapter 3 of this Economic Survey, climate change has the potential to weigh on economic activity in certain parts of the country and impact certain groups of workers. The government is committed to mitigation under the goal of achieving net zero emissions by 2050. A sectoral approach to carbon mitigation is currently being pursued and some initiatives will need to be funded by the government. Further public spending on electric vehicle infrastructure, energy research and development and retraining programmes for displaced workers may all have fiscal costs. There may also be a need to compensate those adversely affected in terms of employment or their costs of living to achieve a just transition. In addition, new investments in electricity generation capacity may require public funding. OECD estimates suggest that the annual capital costs for Australia of new generation capacity will amount to 0.2% of GDP over the period to 2030 under a climate transition scenario (Guillemette and Chateau, 2023). Public infrastructure will also need to be adapted to prepare for more frequent climate hazards and there will be additional needs for agricultural R&D and extension services. At the same time, revenues may come under pressure through the loss of fuel excise and reduced corporate receipts from mining and brown industries.

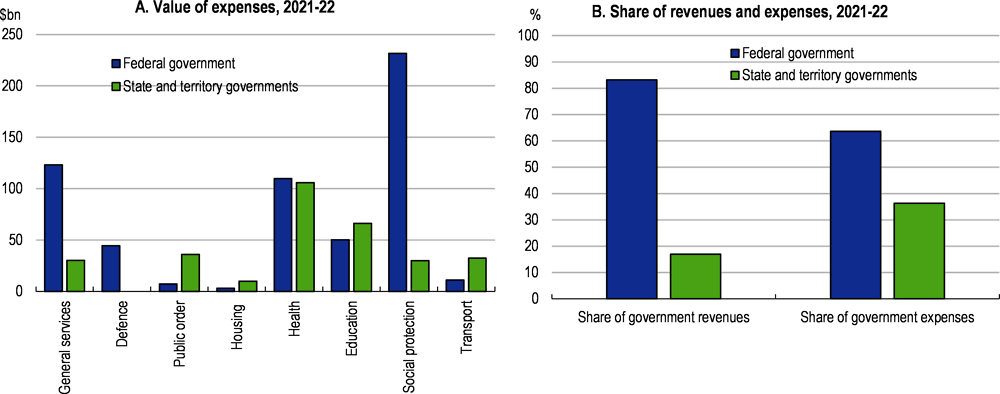

Some of the fiscal pressures will be felt by state and territory governments. As a result, most states and territories are currently projecting a continued rise in the ratio of net public debt to gross state product in the period to 2026-27 (Figure 1.15, Panel A). Health is the major spending item for the states and territories, as they are responsible for the funding of hospitals and ambulance services. The states and territories also have their own emission reduction policies that may generate fiscal costs (see Chapter 3). There is significant vertical fiscal imbalance in the Australian system, with the revenues of state governments falling well short of their spending obligations (Figure 1.17, Panel B). The states are dependent on intergovernmental transfers from the Federal Budget, through the distribution of the revenues from the goods and services tax and special purpose payments. Such transfers are anticipated to amount to 7% of national GDP in 2023-24 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023c). Rising fiscal costs of state and territory governments will thus require improvements in spending efficiency, increased transfers from the federal government or the generation of new own-source revenue from these jurisdictions.

Figure 1.17. State government finances are vulnerable to rising health costs

Fiscal sustainability should remain a focus

The impending fiscal pressures and exposure to commodity price cycles means a prudent approach to fiscal policy needs to be maintained over the years ahead. Australia’s sound fiscal position has enabled public financial support to play a key role in cushioning the impact of past economic shocks, such as the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. The sustainability of public finances will benefit from ensuring the fiscal framework is robust and identifying opportunities to both improve public spending efficiency and undertake sensible tax reforms.

Ensuring a robust fiscal framework

The fiscal policy framework of the federal government is outlined in the Charter of Budget Honesty, legislated in 1998. It advocates a principles-based approach, with the government required to publish a series of reports each year detailing current public finances and the fiscal outlook. The transparency of public finances also benefits from well-designed medium-term budget forecasts, reporting by the Parliamentary Budget Office (an independent fiscal institution) and regular production of intergenerational reports outlining long-term fiscal challenges. In addition, the Treasurer prepares a Fiscal Strategy Statement with each annual budget. In the 2023-24 Budget, the Fiscal Strategy contained an overarching goal of “reducing gross debt as a share of the economy over time” (Box 1.1). This was underpinned by a series of high-level principles including allowing automatic stabilisers to operate, saving the majority of tax upgrades and limiting spending growth until gross debt as a share of GDP is trending down. While not detailed in the fiscal strategy, conservative commodity price assumptions which assume a rapid return to historical norms underpin the budget forecasts, so that spending plans are more closely anchored to underlying rather than current commodity prices.

Box 1.1. The Federal Government Fiscal Strategy – Budget 2023/24

The Fiscal Strategy in Australia is revised each year depending on the priorities of the government and the economic context. The 2023/24 Federal Budget includes the overarching goal of “reducing gross debt as a share of the economy over time”. This is underpinned by the specified intention of:

Allowing tax receipts and income support to respond in line with changes in the economy and directing the majority of improvements in tax receipts to budget repair.

Limiting growth in spending until gross debt as a share of GDP is on a downwards trajectory, while growth prospects are sound and unemployment is low.

Improving the efficiency, quality and sustainability of spending.

Focusing new spending on investments and reforms that build the capability of our people, expand the productive capacity of our economy, and support action on climate change.

Delivering a tax system that funds government services in an efficient, fair and sustainable way.

Source: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023b.

In some other OECD countries also seeking to ensure the sustainability of the public debt-to-GDP ratio, a net spending ceiling has been used as an operational tool and approach to articulating a more explicit fiscal objective (OECD, 2022a; Cordes, 2015). Countries including Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Switzerland and the Netherlands all use some form of spending ceiling. In the Netherlands, the ceiling is set based on a measure of trend growth in revenues. Revenue shortfalls in any given year relative to the spending ceiling are fully accommodated, while revenue windfalls are automatically allocated to budget repair. Ceilings are specified in net terms, so that additional space for spending can be created by discretionary tax increases, while tax cuts need to be offset by more restrictive spending. Focusing fiscal objectives on the spending side of government can be helpful given that there is typically more control over spending than revenues (Casey and Cronin, 2023). This may be especially the case in countries such as Australia where global commodity price developments have a significant influence on tax receipts (Figure 1.18, Panel A): repeated missing of the government’s budget balance objective in the 2011 to 2015 period has been attributed to the downturn in commodity prices (OECD, 2021a;Figure 1.18, Panel B).

Figure 1.18. Commodity price fluctuations have significant implications for public finances

Any further windfall federal revenues in the medium-term should be used to reduce public debt. Once the public debt to GDP ratio is on a sustainably downward path, consideration could be given to diverting windfall commodity revenues to a fund explicitly dedicated to the public sector costs anticipated ahead. Such an approach has been pursued by some other OECD commodity producing countries, such as Chile and Norway. Australia already has the Future Fund, which was initially established in 2006 to manage a pool of funds to pay for future public sector pension liabilities, with several other funds subsequently established under its guardianship (including the Medical Research Future Fund, DisabilityCare Australia Fund, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land and Sea Future Fund, the Future Drought Fund and the Disaster Ready Fund).

The robustness of state and territory fiscal frameworks and the interaction between federal and state budgetary policies should be strengthened. Each state and territory currently have individual legislation, policies and procedures aimed at maintaining fiscal discipline and allocating resources in line with government priorities. The Council on Federal Financial Relations comprising the Federal Treasurer and all state treasurers is responsible for overseeing the financial relationship between the Commonwealth and state and territory governments. In practice, there are significant differences in the strength of fiscal institutions across states and relatively limited dialogue on fiscal policies across jurisdictions, although the federal government interacts extensively with the subnational level on funding of specific programmes. Previously, the Australian Loan Council was used to facilitate fiscal cooperation between the states and the federal government, functioning as a borrowing and deficit control mechanism (Stewart, 2023), but it is no longer in operation. In view of rising debt levels in many states and their exposure to long-term fiscal pressures, institutional arrangements for focused dialogue and coordination of fiscal policies across levels of government should be revived. This should take place through the Council of Federal Financial Relations, while respecting the autonomy of each jurisdiction. Spain is an example of a country with well‑established institutional arrangements to manage general government debt and macroeconomic stabilisation across levels of government (López-Laborda et. al., 2023). To further ensure transparency and benefit public understanding, efforts to publish comparable and regularly updated data on state government finances in a single location are warranted.

Raising public spending efficiency

Improving the efficiency of current and future public spending can help to manage future fiscal pressures. The operation of the health and social security system will be especially important. These areas are funded through general taxation and already collectively account for half of federal government expenditure (Commonwealth of Australia, 2022a) and a large share of state spending. They will be the major sources of public spending growth as the population ages (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021a).

Australia’s health system is well regarded and achieves favourable outcomes, as measured by life expectancy or self-rated health (OECD, 2021b). Even so, an ongoing challenge is the fragmentation of responsibilities across levels of government. Under the Constitution, State and territory governments manage public hospitals and community care for younger people (including child and maternity care), while the federal government is responsible for all primary care and community care for people aged over 65 and Aboriginal people aged 50 and over. These arrangements can result in poor coordination of patient care across parts of the system (OECD, 2015a; Calder et. al. 2019) and are exacerbated by patient data not being easily shared across care settings (Commonwealth of Australia, 2022b). In addition to continuing to work on effective methods of coordination between levels of government, improvements in digital health tools and processes for health data sharing will help support more effective health interventions and cost-effective public investments.

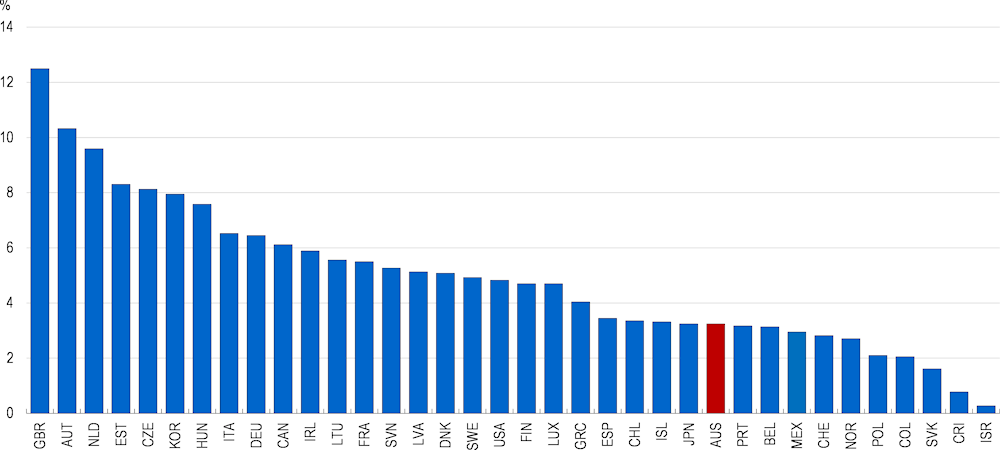

Further encouraging patient care in primary care settings and reorienting spending towards preventive care can also help contain health costs. Hospital admission rates for diseases treatable in primary care are close to the highest in the OECD (OECD, 2021b). This inflates public spending pressures given relatively high unit costs for treating a patient in hospital (OECD, 2020a). Primary care is also particularly well suited to identifying health problems early and introducing preventive measures that can limit future ill-health. Only 3.2% of current health expenditure is on preventive care (Figure 1.19). One of the challenges with preventive care spending is quantifying the often-unobserved benefits that can accrue far into the future. A good example is Victoria’s Early Intervention Investment Framework, which covers policy measures in health as well as a range of other areas (Box 1.2). When introduced at the state level, preventive measures can also have benefits outside the jurisdiction that implements them. Better quantification tools along with strong national dialogue between governments would help promote the understanding of the benefits of preventive measures in reducing future fiscal costs.

Figure 1.19. Preventive health spending is low

Preventive care as a share of current health expenditure, 2022 or latest year

Box 1.2. Victoria’s Early Intervention Investment Framework

The Early Intervention Investment Framework (EIIF) was introduced in the 2021-22 Victorian State Budget, amid rising spending pressures and a recognition of the high fiscal costs of intervening at later stages. The framework funds innovative early intervention initiatives across government departments. All initiatives submitted and funded under the scheme are required to quantify outcome measures and estimate the avoided cost to the government. These estimates are then verified by the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance with an in-house model using advanced data analytics in collaboration with departmental subject matter experts.

A portion of the avoided costs (savings to the government) are set aside to be reinvested into EIIF initiatives in future budgets. This ‘invest to re-invest’ approach embeds early intervention into the budget process and progressively increases the amount of funding to early intervention initiatives over successive budgets, re‑balancing the system towards prevention and away from increasing demand pressures in acute services.

In recognition of the challenges associated with quantification of preventive measures, funding has been allocated to enhancing shared data resources and building greater data analytical capability. This supports both ex-ante decisions about how to invest, and ex-post monitoring and evaluation. In a broader sense, the quantification helps inform the Government’s understanding of the investment return of an early intervention initiative.

Source: Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance, 2022.

Reforms to the Age Pension can also offset the impending spending pressures. The Age Pension, a means-tested payment to older individuals, is a core pillar of the retirement income system. This government payment provides a safety net for retirees but can also supplement private superannuation or other savings. A 2020 government review concluded that the retirement income system in Australia is fiscally sustainable (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). This partly reflects Australia’s compulsory superannuation arrangements, whereby employers make mandatory contributions equivalent to 11% of employee wages or salary to their superannuation fund. The stock of superannuation assets currently stands at around AUD3½ trillion (140% of GDP). Even so, publicly funded income support for seniors still accounts for about one quarter of all government spending on social welfare. In 2017, the government announced an increase in the Age Pension qualifying age to 67 by 2023-24. A further increase in the qualifying age to reach 70 by 2037 was proposed, but subsequently abandoned. In future, linking increases in the pension age to some fraction of the increase in life expectancy of older Australians should be considered.

More generally, public spending efficiency can be promoted through better processes around the selection and evaluation of government projects. The Productivity Commission recently highlighted the inadequate use of rigorous cost-benefit analysis for both major infrastructure projects and in other government activities, such as defence and social services (Productivity Commission, 2023a). Credible vetting of the assumptions and inputs used in cost-benefit analysis should be considered for projects valued above a certain threshold. For infrastructure spending, Infrastructure Australia (the country’s independent infrastructure advisor) would be a clear candidate to either undertake cost benefit analysis or accredit the evaluations of state independent infrastructure advisory bodies. Regarding policy evaluation, an analysis of 20 federal government programmes with costs over $200 billion highlighted that evaluation frameworks were absent or missing in 95% of cases (Winzar, et. al. 2023). The establishment of the Australian Centre for Evaluation in the Australian Treasury in the 2023-24 Budget provides a vehicle for the Government to promote the systematic use of high-quality evaluation to support evidence-based policy decisions. A key function of the centre will be to support Commonwealth entities and companies to meet the requirements and policy intent of the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy (which came into effect in December 2021), which sets out the Government’s expectations in relation to evaluating government programs and activities.

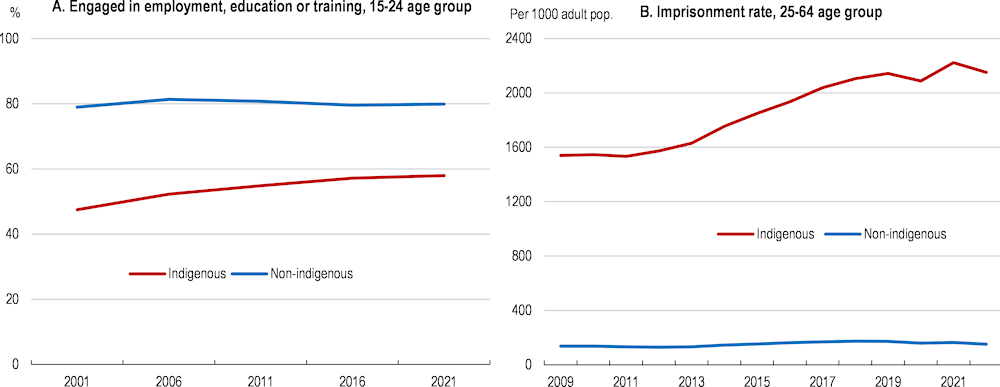

Better design and evaluation of policies and programmes related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should also be a priority. Life expectancy of Indigenous Australians born in 2015-17 is eight years below that for non-Indigenous Australians and their employment rates remain 20 percentage points lower (Figure 1.20, Panel A). Imprisonment rates for working age Indigenous Australians were 14 times higher than for non-Indigenous people in 2022 (Figure 1.20, Panel B). Despite decades of new policies and changes to existing ones, little is known about what policies focused on Indigenous Australians work and why, and there is no coordinated approach to policy evaluation across governments.

Shared decision-making authority between governments and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in developing and implementing policies has been increasingly emphasised. This was a core commitment of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap agreed by all Australian governments along with the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations in 2020. However, a draft review into progress on the agreement by the Productivity Commission in July 2023 found that governments are generally not sufficiently investing in partnerships or enacting the sharing of power necessary if decisions are to be made jointly (Productivity Commission, 2023b).

The evaluation of existing policies impacting on Indigenous Australians is also underdeveloped. The Productivity Commission has proposed an Indigenous Evaluation Strategy that gives guidance for Commonwealth agencies in response (Productivity Commission, 2020a). The newly established Australian Centre for Evaluation has the potential to play a clear stewardship role in implementing the Indigenous Evaluation Strategy across the Commonwealth Government. Ongoing coordination between the Indigenous Evaluation Committee of the National Indigenous Australian’s Agency with input from the Australian Centre for Evaluation will help identify future opportunities to strengthen evaluation guidance and processes in a culturally appropriate way for both Indigenous-specific and mainstream policies that affect Indigenous Australians.

Figure 1.20. Indigenous Australians continue to experience much worse outcomes in key areas

Tax reforms to address fiscal pressures

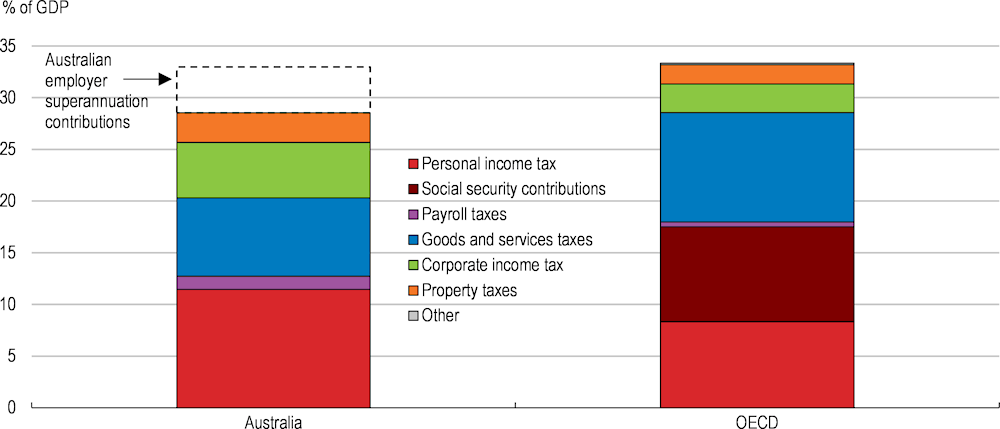

The combination of a persistent structural fiscal deficit and future spending pressures suggests the authorities will need to consider avenues for raising further revenues. On the face of it, taxation as a share of GDP is low by OECD standards: at 28.5% in 2020, compared with 33.6% on average in the OECD (Figure 1.21). However, Australia does not levy social security contributions and including compulsory superannuation payments by employers (which fund private pensions) suggests a burden only slightly below the OECD average. Examining the tax mix, Australia relies more heavily on corporate taxes and less on goods and services taxes than most other OECD countries. The sum of personal income taxation and superannuation contributions is roughly equivalent to the sum of personal income taxation and social security contributions in the average OECD country.

Personal income taxation is expected to rise as a share of total taxation in the coming years (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2022a). This partly reflects a lack of indexation of tax thresholds in a highly progressive personal taxation system, with ad hoc tax cuts only partly offsetting the impact of nominal wage growth pushing employees into higher tax brackets (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015). In 2019, the government legislated several stages of tax cuts starting from the 2018-19 financial year. The aggregate effect of these tax cuts is to return the proceeds of bracket creep to households, though they are slightly regressive because they overcompensate those in the highest income quintile (Phillips et. al. 2023). A high reliance on personal income taxation is a risk in an environment of a declining share of the population active in the labour market as the population ages (Rouzet et. al. 2019). This is especially the case given the relatively light taxation of pension income in the Australian system. In addition, high personal income taxation can have adverse impacts on economic growth, largely through weakening the attachment of below-average income earners to the labour market and reducing the marginal benefits to higher income earners of increasing labour supply (Akgun et. al., 2017). Consequently, in raising additional tax revenues, the authorities should not rely on further increases in personal taxation but should look to other tax heads that are less likely to come under pressure from an aging population and are less distortionary for economic activity.

Figure 1.21. Goods and services taxes account for a lower share of the tax mix

Tax revenues as a share of GDP, 2020

Note: Data are for 2020, the most recent comparable year. The “Australian employer superannuation contributions” includes super guarantee contributions and defined benefit contributions.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics Database; Australian Prudential Regulation Authority.

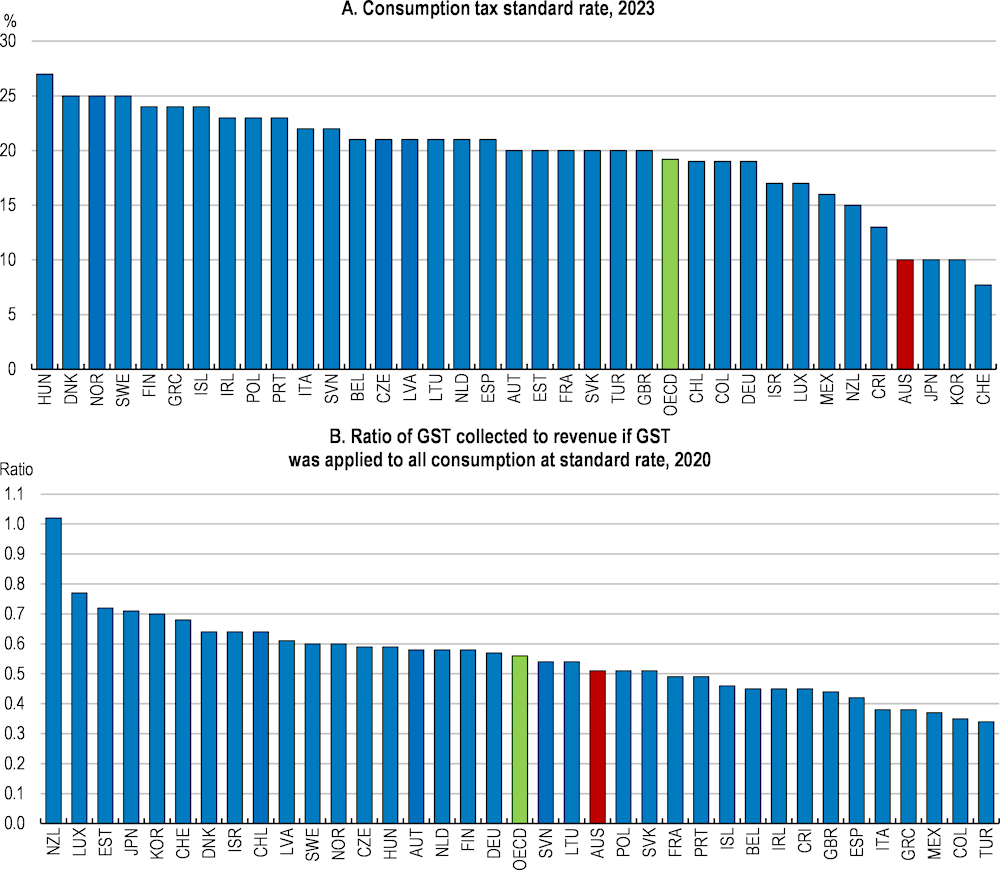

Goods and services taxes are a more resilient tax base to an ageing population (Colin and Brys, 2019) and can help rebalance the sharing of the tax burden between people in employment and the retired population. They are also more difficult to evade and have weaker disincentive effects than income taxes (Akgun et. al., 2017). Revenues from taxes on goods and services accounted for 26.5% of total taxation in Australia in 2020 compared with 32% in the average OECD country. This partly owes to the low rate of 10% for Australia’s Goods and Services Tax (GST) and more exemptions than in other OECD countries (Figure 1.22). GST revenues as a share of both total taxation and GDP have been falling over the past decade and are expected to continue doing so with a rising share of GST-free items in household consumption bundles (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2020).

There are challenges to raising more revenue from the GST. As highlighted earlier, the tax is collected by the federal government and distributed to the states. Changes to the base or to the rate would require unanimous agreement of state/territory and federal governments and passage of legislation through Commonwealth Parliament. Increasing the GST could also be regressive, as it is taxed at a flat of 10% meaning it typically accounts for a larger share of income for lower income households. Even so, the value of GST exemptions in Australia are disproportionately captured by higher income households (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023d). This suggests that a base-broadening GST reform could be accompanied by a compensation mechanism for lower income households (such as increases in government benefits) while still raising revenue. Rough estimates suggest that a reform that combined closing the most significant GST exemptions with a compensation package for low-income households could still raise 0.7% of GDP in additional government receipts (Box 1.3).

Figure 1.22. The GST rate is low and there are significant exemptions

Note: Panel B is the “VAT Revenue Ratio”. For Türkiye, data is 2019.

Source: OECD Consumption Tax Trends database.

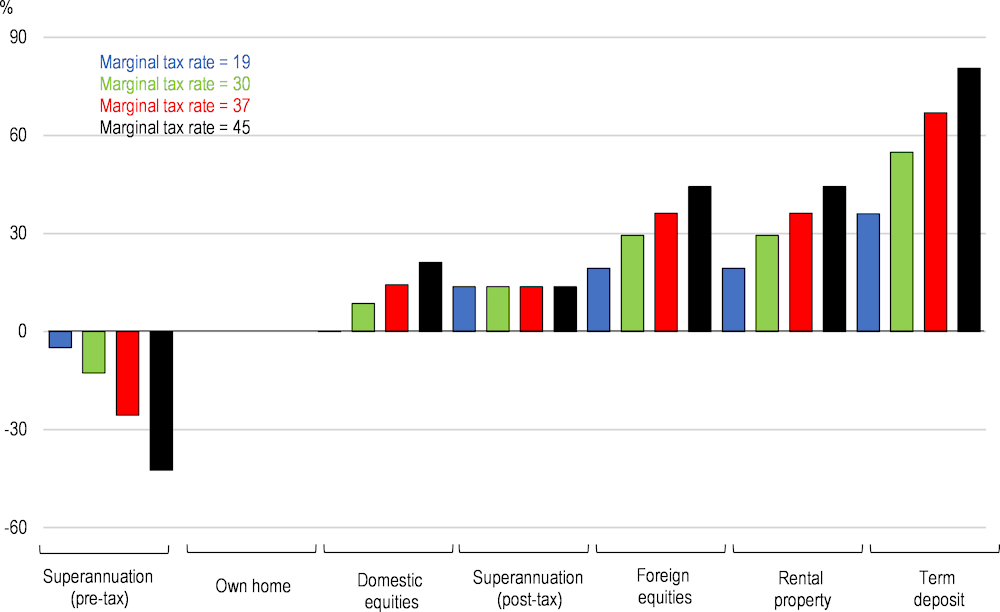

Tax treatment across different savings vehicles differs markedly (Figure 1.23). This partly reflects some saving forms, such as bank interest or rental income, being taxed as personal income at an individual’s marginal rate and other saving forms being subject to special concessional tax treatment. While Australia has close to the highest marginal effective tax rate on bank deposits and rented residential property income in the OECD, the rates on private pension savings are well below average (OECD, 2018b). These differences, combined with a high level of complexity in the various tax provisions, can encourage costly tax planning schemes and distort the flow of savings (Varela et al., 2020). The fact that older and higher income households have a relatively high share of assets in those savings vehicles more lightly taxed can exacerbate both intra- and intergenerational inequalities.

Figure 1.23. Superannuation is much more lightly taxed than some other savings vehicles

Real effective marginal tax rate on long-term savings vehicles, by marginal tax rate (%)

Notes: Real effective marginal tax rates calculated against an expenditure tax benchmark (i.e. if tax were paid on income when earned and then both dividends and withdrawals were tax free).

Source: Coates and Moloney (2023).

Further reducing tax concessions on private pensions would be a step towards greater tax neutrality across different savings vehicles and could raise further revenue. At present, most contributions and earnings in Australia’s superannuation system are taxed at a flat rate of 15%, while in retirement, earnings from assets up to AUD1.9 million and withdrawals are generally untaxed (Parliamentary Budget Office, 2023). This implies that income channelled through the schemes is undertaxed over the lifecycle, particularly for richer people with high marginal tax rates. Superannuation tax concessions are projected to grow as a percentage of GDP, with the fastest growing component being earnings tax concessions (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). In particular, the tax exemption on earnings in retirement is growing as median superannuation balances at retirement are rising as the system matures.

According with a recommendation in the previous OECD Economic Survey of Australia, the authorities have recently announced their intention to restrict the concessional tax rates by increasing the headline tax rate from 15% to 30% on earnings in superannuation accounts with balances exceeding AUD3 million (Table 1.4). If legislated, the increased tax will apply to earnings on amounts over AUD3 million, commencing in July 2025 and earnings under this threshold will continue to be taxed at 15%. Further reform options include reducing the annual concessional contribution cap under which individuals can make additional contributions from their pre-tax income (currently set at AUD27,500 per annum) or taxing superannuation earnings in the retirement phase. Estimates from the Grattan Institute suggest that taxing superannuation earnings in retirement at 15% coupled with capping pre-tax contributions at AUD20,000 would raise around 0.3% of GDP in additional revenue (Box 1.3). However, more stringent tax treatment of superannuation may also lead to increased use of other vehicles for tax planning purposes, such as trusts. The number of trusts has grown rapidly over the past two decades (Sainsbury and Breunig, 2020), with these vehicles potentially used to reduce household tax liabilities by splitting income to use all beneficiaries’ tax-free thresholds (De Silva et. al. 2018). Further efforts to understand and evaluate the various complex trust structures that exist and the value of income being directed through them would be worthwhile.

Table 1.4. Past OECD recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations in previous Survey |

Action taken since September 2021 |

|---|---|

|

Further shift the tax mix away from income taxes (especially personal income tax) and inefficient taxes (including real-estate stamp duty) and towards the Goods and Services Tax and recurrent land taxes. Reduce some of the concessions for the taxation of private pensions, particularly those that favour high income earners. Reduce the capital gains tax discount. Assess the distortionary impact of the current two-tier corporate tax system. |

On 28 February 2023, the federal government announced it would reduce the superannuation tax concessions for individuals with total superannuation balances above AUD3 million. From 1 July 2025, the Better targeted superannuation concessions reform will bring the headline tax rate to 30 per cent, up from 15 per cent, for earnings corresponding to the proportion of an individual’s superannuation balance above $3 million. |

|

Further increase the unemployment benefit rate and consider indexing the rate to wage inflation. |

In May 2023, the government announced a modest increase in the base rate for JobSeeker and other working age and student payments of base rate by AUD40 per fortnight and extended eligibility for the existing higher single JobSeeker payment rate to those in the 55-60 age bracket. There was also a 15% increase in the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance. |

|

Embed the Productivity Commission Indigenous Evaluation Strategy in the policy design and evaluation process of all Australian Government agencies for both Indigenous-specific and mainstream policies that affect the Indigenous population. |

No action taken |

|

Implement a medium-term fiscal strategy with targets that are associated with specific timeframes or conditional on measurable economic outcomes. |

No action taken |

|

Task an independent fiscal institution, such as the Parliamentary Budget Office, with both formal evaluation and monitoring of the government’s fiscal strategy |

No action taken |

There are other changes to the tax system that can benefit fiscal sustainability, including by spurring economic growth. Replacing state-level transaction taxes on real estate with a recurrent land tax would promote labour mobility and the transfer of assets for more appropriate uses. The Australian Capital Territory has already begun making this transition and the Victorian government recently announced such a shift for commercial properties. Further avenues for increasing the taxation of natural resources should also be considered. As discussed in previous OECD Economic Surveys, a move towards taxing resource rents, rather than royalties could improve the climate for resource-sector investment and exploration (OECD, 2018c). In Australia, natural-resource taxation is primarily a state-level responsibility, with the federal government only having taxing rights on offshore natural resources. There was previously a Minerals Resource Rent Tax levied on 30% of the profits of mining companies once they exceed a dollar value threshold. However, this was repealed in 2014, two years after being introduced. There could also be consideration given to introducing an inheritance and estate tax, which are levied in most other OECD countries (OECD, 2021c), as these are less distortive to growth than labour taxes and can help address intergenerational inequality. Australia does not have an inheritance tax, after such levies were removed at both the state and federal level four decades ago.

Box 1.3. Budgetary impact of recommendations

The following estimates are taken from a variety of sources and quantify the fiscal impact of selected medium-term reforms with long-term fiscal impacts. There is significant uncertainty around these estimates.

Table 1.5. Illustrative fiscal impact of selected reforms

|

Policy |

Scenario |

Additional annual fiscal cost (-) or revenue (+), percentage points of GDP |

|---|---|---|

|

Spending measures |

||

|

Further raising unemployment benefits |

Unemployment benefits are increased to the point where the minimum amount a JobSeeker Payment recipient receives through private income and government payments equals the OECD relative measure of poverty.1 |

-0.4% |

|

Raising parental leave |

Increasing public expenditure on maternity and parental leaves per live birth to the OECD average. |

-0.3% |

|

More efficient health spending |

Encourage patient care in primary care settings and increase the focus on preventive care. |

+ |

|

Revenue measures |

||

|

Reduce superannuation tax concessions |

A package of changes including taxing superannuation earnings in retirement at 15% and cap pre-tax contributions at AUD20,000.2 |

+0.3% |

|

Broaden the Goods and Services Tax base |

Eliminate Goods and Services Tax exemptions for education, healthcare, food, water, sewerage and drainage and introduce compensation for low-income households equivalent to 0.3% of GDP. 3 |

+0.7% |

Note: Behavioural changes in response to a tax or spending change are not taken into account. Reform recommendations with fiscal impacts of less than 0.1% of GDP are not included. The savings associated with the key recommendation to reduce National Disability Insurance Scheme Costs are already factored into the government’s central budget projections. The key recommendation to further encourage patient care in primary care settings and increase the focus on preventive care would also be expected to bring budgetary savings, but no reliable estimates exist for estimating the impact (reflected with the “+” sign in the table).

Source: 1. Partially based on calculation from Parliamentary Budget Office (2020). 2. Based on estimates from Coates and Moloney (2023). 3. Based on Commonwealth of Australia (2023d).

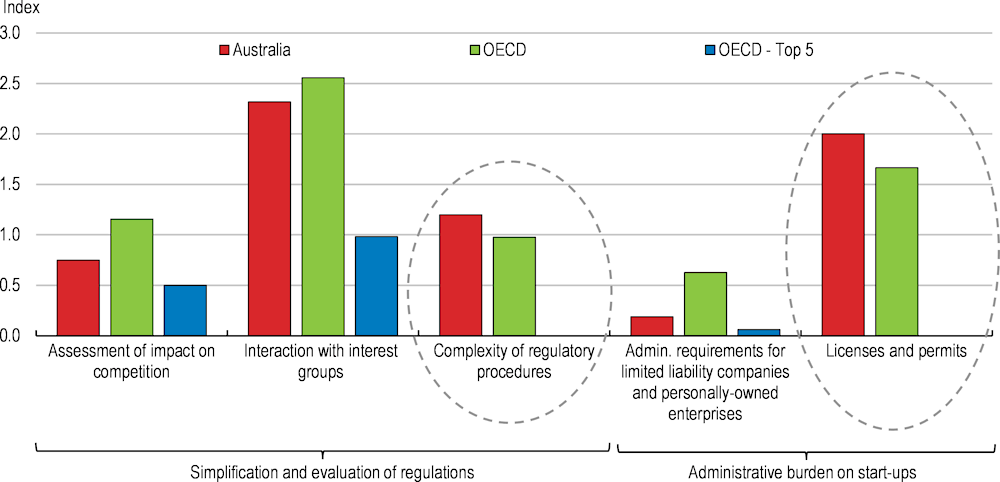

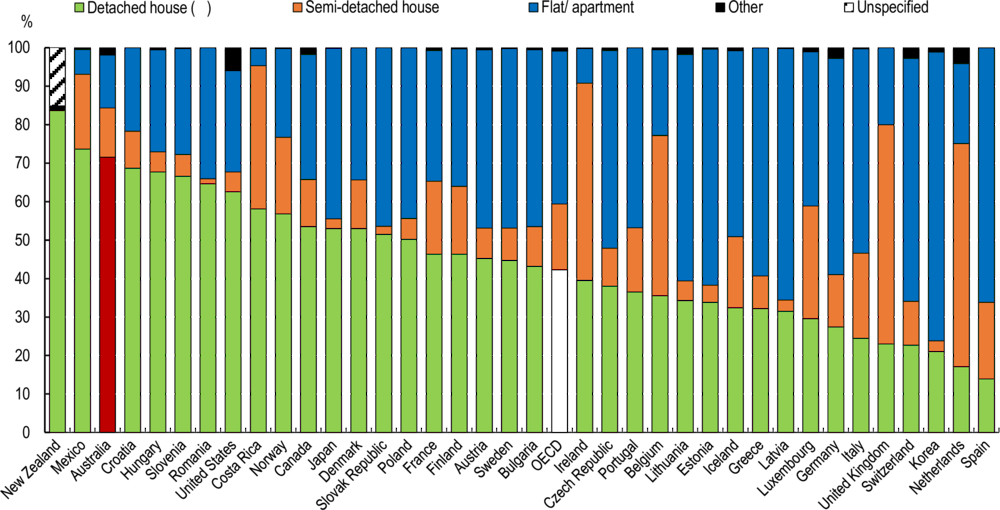

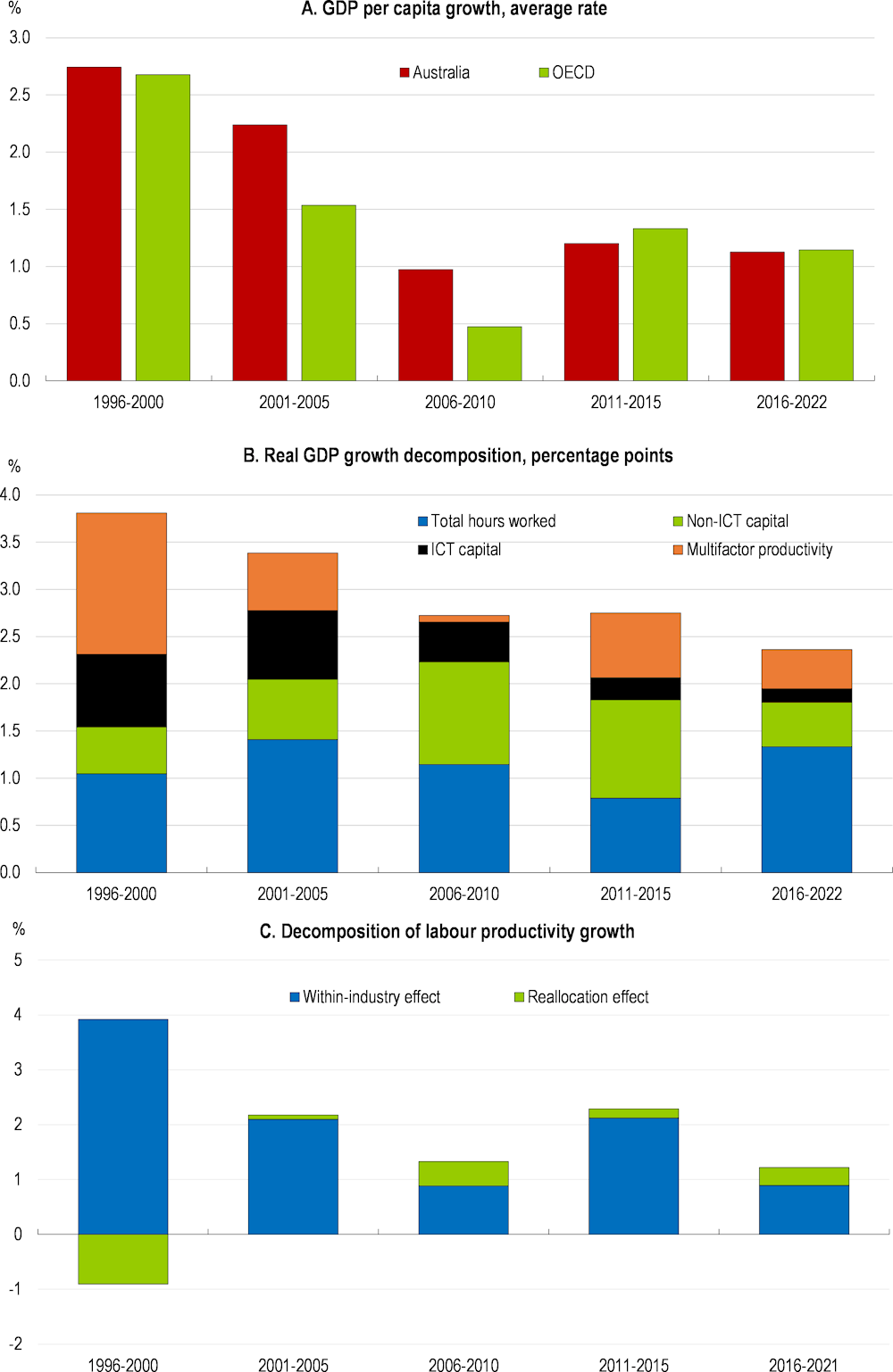

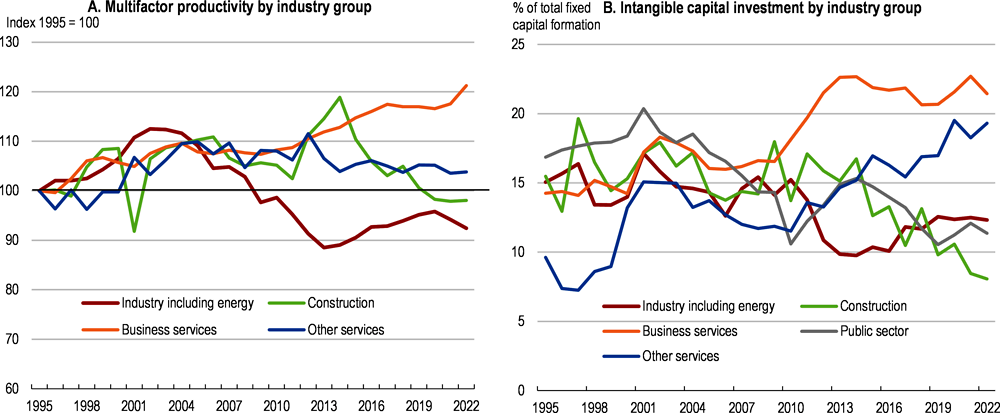

Raising medium-term economic prospects