Ben Westmore

OECD Economic Surveys: Australia 2023

2. Fully realising the economic potential of women in Australia

Abstract

Gender inequalities have steadily declined, but remain particularly visible in the labour market. Australian women have lower employment rates, hourly wages and hours worked than their male counterparts. Childbirth is particularly disruptive for the labour market experience of women in Australia. Reforms to the tax and benefits system, childcare and parental leave arrangements are all needed to reduce the barriers to female labour participation of mothers. At the same time, ensuring the adequacy of unemployment benefits will support the living standards of many low-income women given that they have become an increasing share of recipients. Single mothers face particularly high poverty risk and would also benefit from more robust arrangements around child support payments from non-custodial parents.

Introduction

Gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but also a keystone of a prosperous, modern economy that delivers sustainable inclusive growth. It is essential for ensuring that men and women contribute fully at home, at work and in public life, for the betterment of societies and economies at large. Equal and fair treatment allows everyone to fulfil their potential. However, gender inequalities persist across OECD countries in social and economic life. Achieving gender equality is one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the objective of the 2013 OECD Council Recommendation on Gender Equality in Education, Employment and Entrepreneurship (OECD, 2017) and the 2015 OECD Council Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life (OECD, 2016).

There has been steady progress in improving gender equality in Australia over recent decades, though gender gaps persist that are symptomatic of women not being able to fully realise their potential. Making further improvements on gender equality is a key objective of the Australian government. A National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality is under development and will consider the advice of the recently released report by the Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce (Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce, 2023). Reforms have been undertaken to expand Paid Parental Leave and improve access to childcare, with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and Productivity Commission currently undertaking further reviews into the childcare sector. The government’s Employment White Paper, which explores the policies needed for Australia’s future labour market, has a strong emphasis on improving women’s economic participation and equality. In addition, gender responsive budgeting has been further expanded, with key steps and processes for gender assessment and gender impact analysis incorporated into formal budget and Cabinet processes.

There would be substantial benefits to the economy from raising opportunities for women, in addition to the direct benefits for women in Australia and their families. Amid an ageing population, boosting labour force participation for working aged women can be a key source of future economic growth. In addition, improved gender equality can better enable people to be matched with activities where their abilities and interests lie. This can be a key channel for increasing productivity and economic growth (Hsieh et. al. 2019), as well as overall wellbeing. There is also evidence that a more gender diverse workforce, at both the worker and management level, is more productive (Criscuolo et al., 2021).

The current state of gender equality

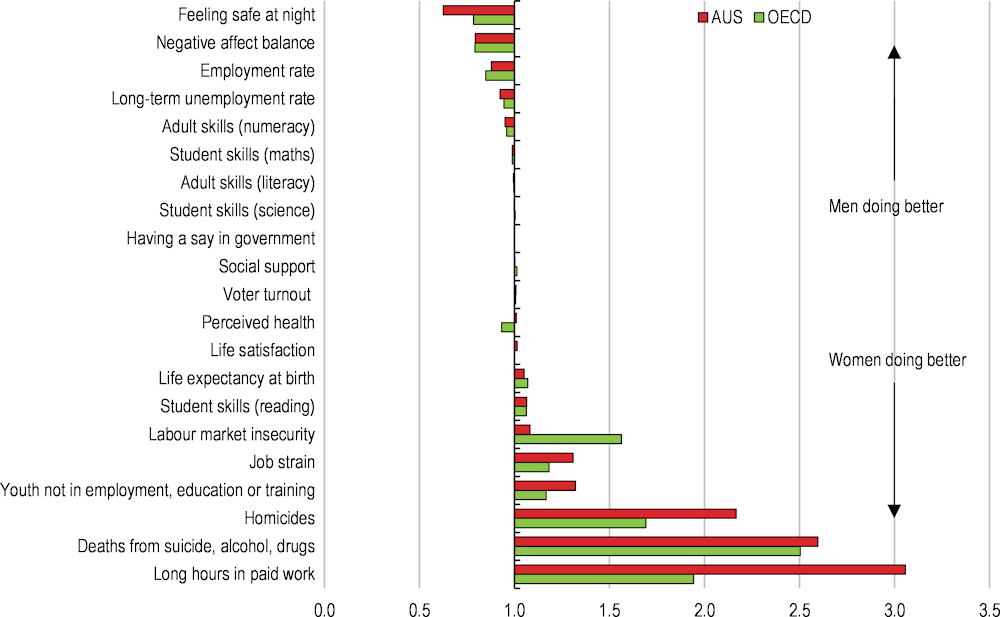

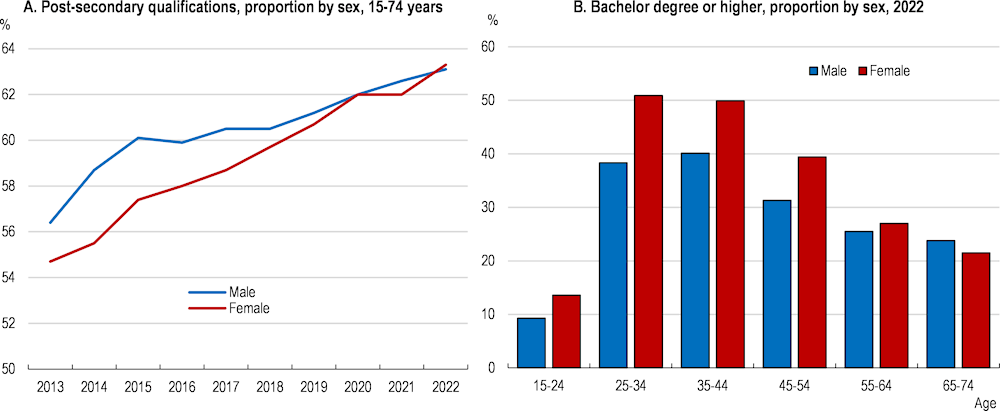

The wellbeing of women in Australia exceeds that of men in areas such as health (as measured by life expectancy), risk of death from homicide, suicide, alcohol or drugs (Figure 2.1). Women in Australia are now also more likely to be highly educated, following a significant increase over the past decade in the share of women holding post-secondary qualifications (Figure 2.2, Panel A). This is especially the case for the younger graduate cohorts (Figure 2.2, Panel B): the proportion of women in the 25-44 age group with a bachelor’s degree or higher was over 10 percentage points above that for their male counterparts in 2022.

Figure 2.1. Gender differences in wellbeing outcomes exist along many dimensions

Gender ratios (distance from parity) for selected indicators of current well-being (higher numbers indicate a better outcome), 2019 or latest available year

Figure 2.2. Women in Australia are highly educated

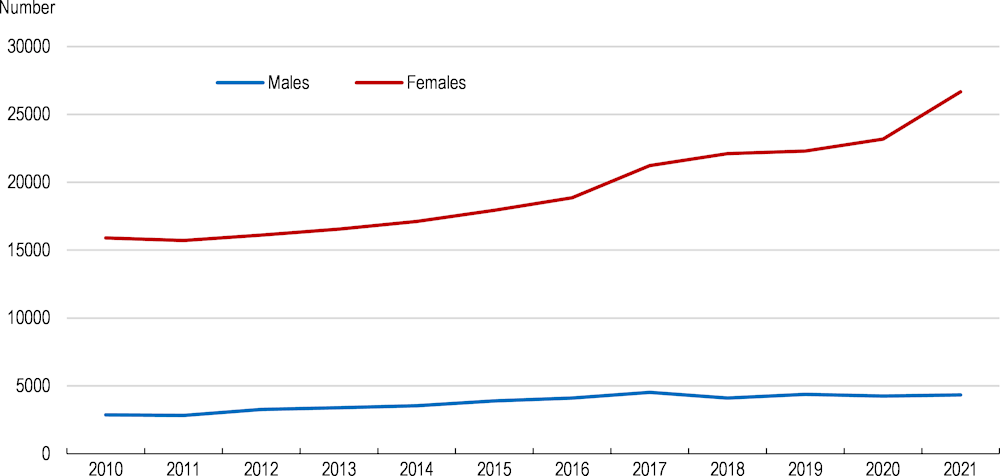

Women in Australia are still behind their male counterparts in other dimensions. Safety of women is a concern, with surveys suggesting that the gender gap in perceived safety is large compared to other OECD countries. Feelings of unsafety can fundamentally reduce quality of life and narrow women’s choice of economic activities to domains where they feel safe. In much the same way, the existence of sexual harassment can have pervasive economic effects. In recent years, reports of sexual harassment made by women in Australia have increased, while those for men have remained largely stable (Figure 2.3). This may be a welcome development to the extent that it reflects greater confidence of women reporting harassment, but the volume of such cases - and gap with those reported by men - remains large. In the workplace, national surveys report that 41% of women and 26% of men have been sexually harassed in the past five years (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2022). Furthermore, some more economically disadvantaged cohorts such as those with a disability and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders disproportionately report workplace sexual harassment.

Figure 2.3. Women are more likely than men to report being sexually harassed

Reported cases of sexual harassment, by gender

At work, women are less likely to experience job strain or be subjected to long working hours than men. However, this reflects their weaker integration into the labour market. Women in Australia have lower employment rates, lower hours worked, lower earnings and a higher long-term unemployment rate. Entrepreneurship rates are notably lower for women and less than one in six Australian inventors is female. While significant progress has been made in these dimensions over past decades, gaps remain wide. Consequently, further efforts at achieving the potential of women should focus primarily on improving their labour market experience and it is this dimension that will be the focus of much of the discussion of this Chapter.

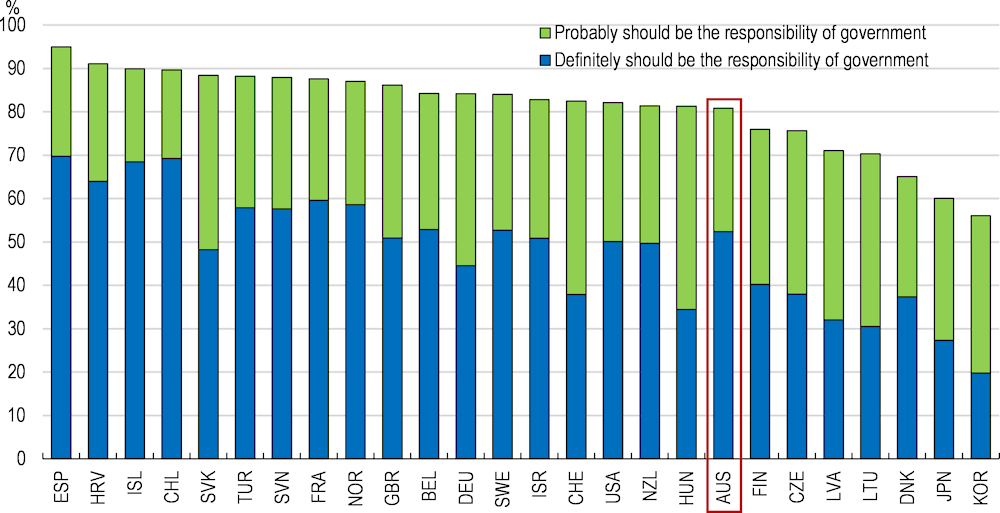

Figure 2.4. Most Australians believe the government has a responsibility to promote gender equality

Share of respondents that believe it should be the responsibility of government to promote gender equality

There is a role for government in reducing gender inequality. Around 80% of the surveyed population see it as at least the partial responsibility of the government to promote gender equality (Figure 2.4). Nonetheless, only around half the surveyed population see it as definitely the responsibility of the government, lower than in many other OECD countries. This highlights the need for the authorities to actively engage social partners and other stakeholders. The government should have a leading role in setting objectives and the overall strategy for improving gender equality, but this should be done in close consultation with key stakeholders. The National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality, developed in consultation with diverse voices across Australia, will be an important mechanism to elevate and prioritise actions that will improve gender equality. An ongoing challenge is collecting representative, timely and regularly updated data on specific cohorts of diverse women, including women with a disability, Indigenous Australian women and those living in remote areas. Better data will enable a closer examination of the intersections between the different dimensions of diversity, which may have implications for policymakers.

Gender inequality in the labour market

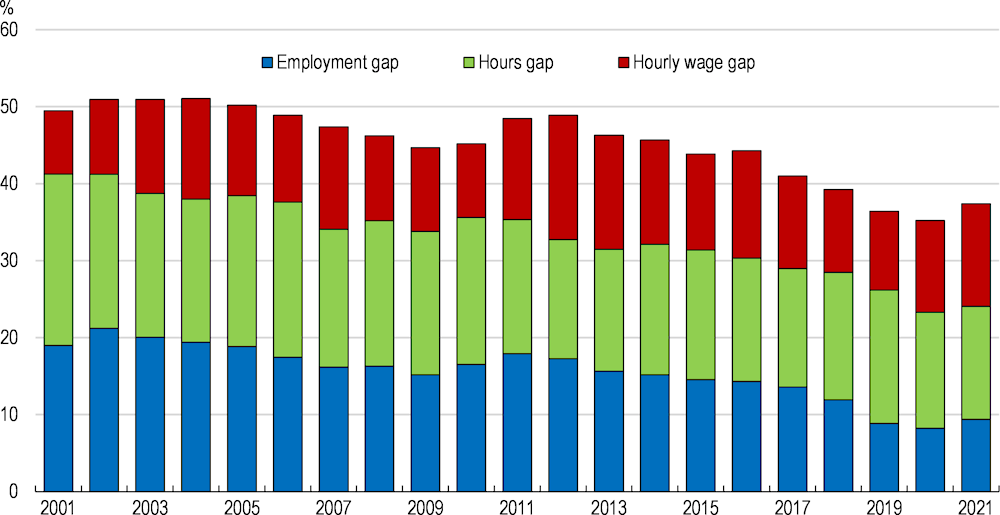

Gender inequality in the labour market can be observed in differences between men and women in employment rates (employment gap), the intensity of work (hours gap) and the amount workers are paid per hour (hourly wage gap). Overall, women’s labour income is 40% lower than for men on average. Decomposing the gender gap in labour income highlights that all three factors play a role in the Australian context (Figure 2.5), though the aggregates mask significant differences across population cohorts. Overall, the labour income gap has declined over the past few decades, mostly driven by an increase in the share of women in employment.

Figure 2.5. The gender labour income gap arises from the extent, intensity and rewards from work

Decomposition of the gender gap in labour income

Note: The decomposition follows the methodology outlined in Chapter 6 of OECD (2018).

Source: HILDA; OECD.

Gender gaps in the employment rate

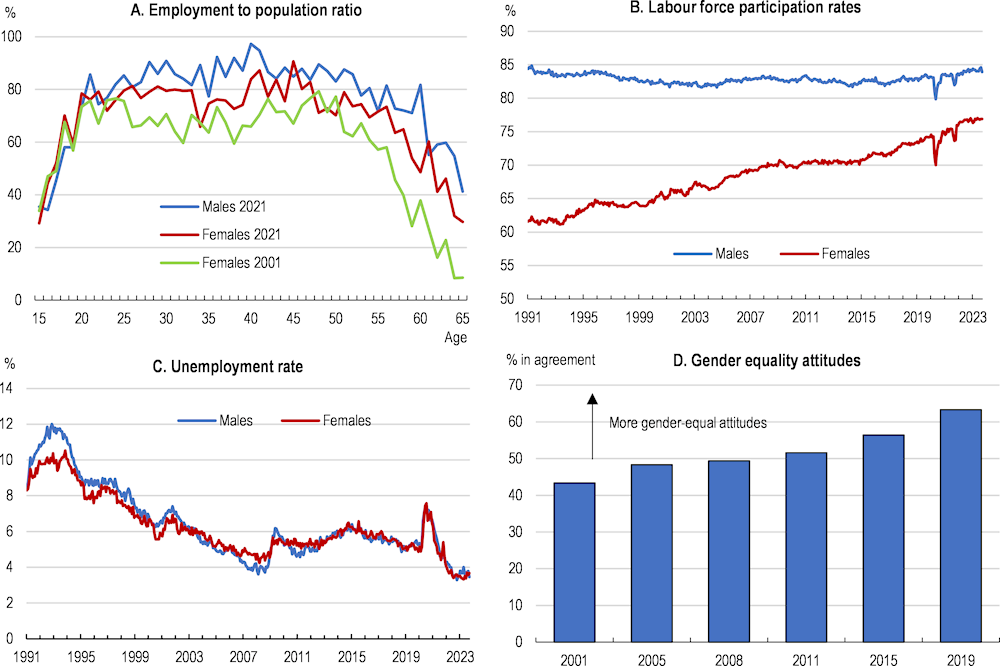

The increase in the employment rate of women in Australia has occurred across age cohorts (Figure 2.6, Panel A). This has largely reflected a steady increase in the female labour force participation rate (Figure 2.6, Panel B), as the unemployment rate of women has been broadly aligned with that of men (Figure 2.6, Panel C). There have been various factors contributing to the rise in women’s participation, including rising educational attainment of women (National Skills Commission, 2021), changing social attitudes to women working (Churchill and Craig, 2022; Figure 2.6, Panel D), the introduction of paid parental and caregivers leave and subsidised child care (United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Policy Responses to Low Fertility, 2015) and the growth of more flexible work arrangements (Heath, 2018).

Figure 2.6. Female labour participation has increased substantially

Note: In Panel B, participation rates are for the population aged 15-64. In Panel D, the measure is calculated as the share of the surveyed population that disagreed with the statement that “it is better for everyone involved if the man earns the money and the women takes care of the home and children” in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics Database, HILDA, OECD.

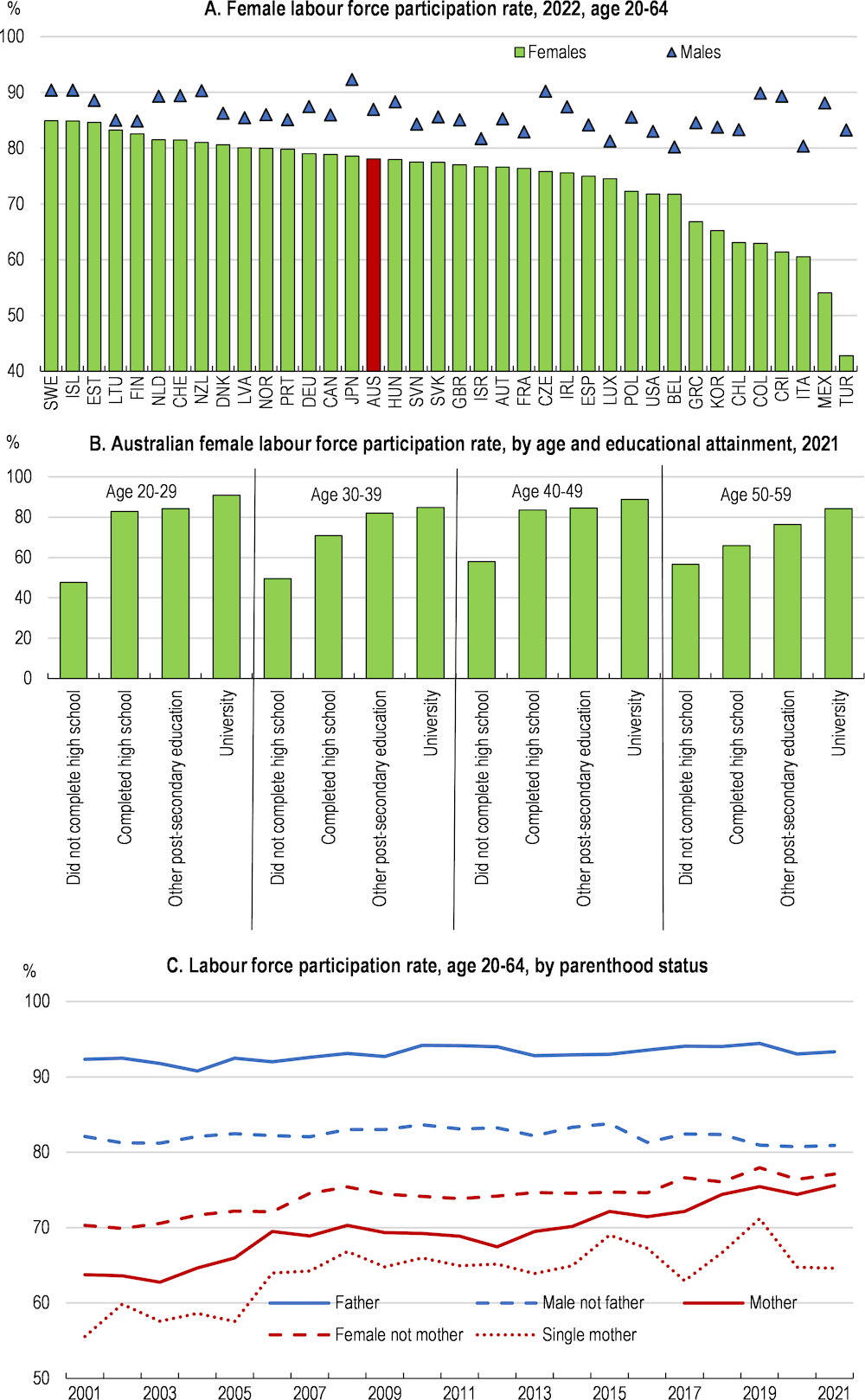

Despite the progress made, the labour force participation rate remains lower, and the gap to the participation rate of males larger, than in some peer OECD countries (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Women who did not finish high school have particularly low participation rates (Figure 2.7, Panel B). The participation rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women aged 15-64 was around 17 percentage points lower than for non-indigenous women at the time of the 2021 Census. There is also evidence that women born overseas have a lower participation rate than those in the native-born population (Box 2.1), which accords with the fact that they are more likely to undertake unpaid childcare than Australian women (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023a). For those women who have completed high school or higher education, participation rates are typically lower for those in the 50-59 age group and in the age group with the highest fertility rate (30-39). The latter is consistent with lower participation of mothers than women without children (Figure 2.7, Panel C). In contrast, fathers are much more likely to participate in the labour force than men without children.

Figure 2.7. There remains scope to further increase female participation

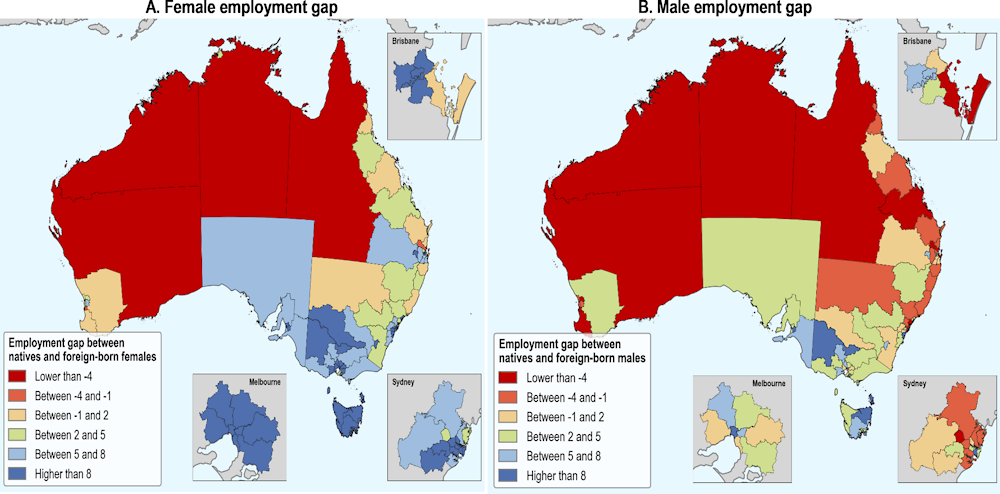

Box 2.1. Employment rates of women born overseas

In Australia, migrants are less likely to be employed compared to native-born individuals. This partly reflects the lower employment rates of migrant women. Like most other OECD countries, the difference in the employment rate between native-born and migrants is significantly larger for women than for men (OECD, 2022). In 2019, the native-migrant gap for men was negligible at only 0.5 percentage points, while the difference in employment rates between women born overseas and native-born women exceeded eight percentage points. The primary factor explaining the employment rate gap between women born overseas and native-born individuals is relatively low labour force participation, rather than higher unemployment rates. Examining employment gaps separately for women (Figure 2.8, Panel A) and men (Figure 2.8, Panel B) highlights the spatial dimension of these gaps. However, in all SA4 regions except for the Wheat Belt in the south of Western Australia and the Outback in Queensland, the employment gap between natives and those born overseas is more pronounced for women than men.

Figure 2.8. The gap in employment rates with the native-born population is larger for women born overseas

Employment gap between native-born and migrants by gender, SA4 regions

Note: The figure presents the percentage point difference in the employment rate of native-born and foreign-born among the working-age population (15-64 years) in Australia disaggregated by SA4. A positive value indicates a higher employment rate among the native-born. Panel A presents the female working-age population. Panel B presents the male working-age population. Data are for 2016.

Source: Australian Census of Population and Housing.

Source: OECD (2023d), “Regional productivity, local labour markets, and migration in Australia”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 39, OECD Publishing, Paris.

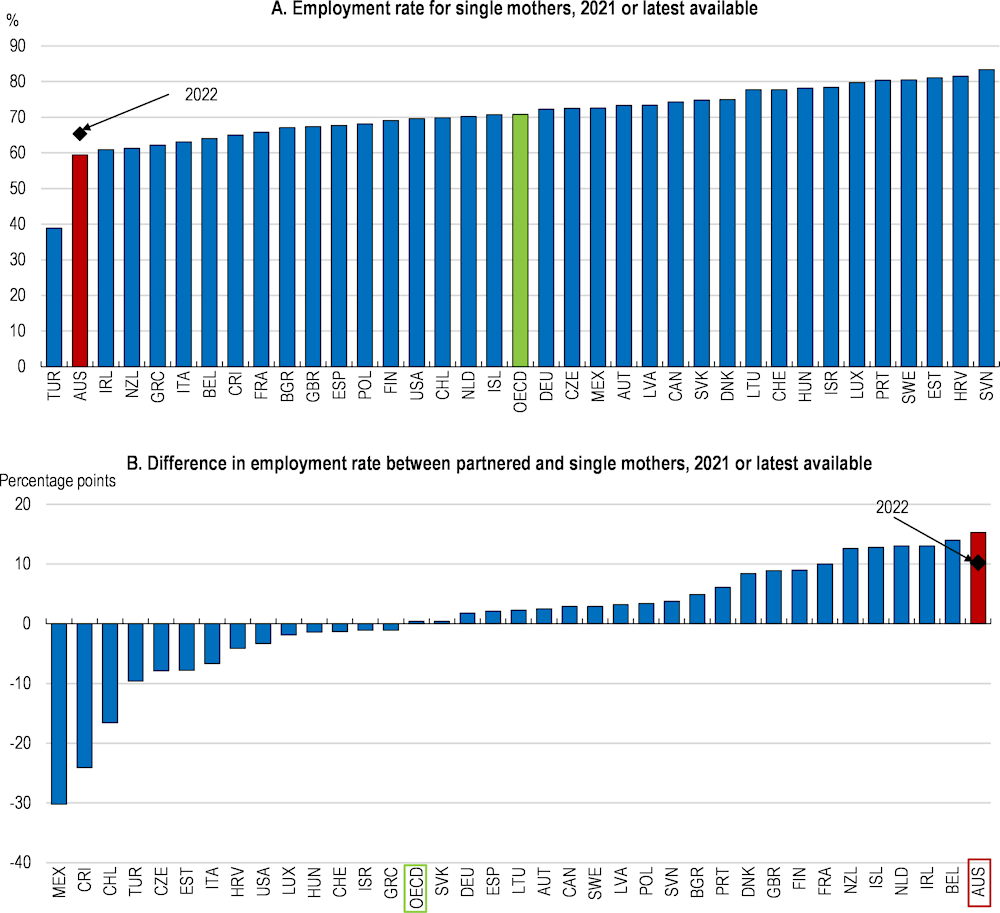

Employment rates are especially weak for single mothers. In 2022, around 11% of Australian families were single mother families. Less than 50% of single mothers with a child aged 0-4 were employed, compared with over two thirds of coupled mothers with children in the same age bracket. While the employment rate of single mothers in Australia has increased notably over the past few years, it remains low compared with other OECD countries (Figure 2.9, Panel A), even those with lower aggregate female participation rates. The gap with employment rates of coupled mothers is comparatively large (Figure 2.9, Panel B). According to HILDA data, around 35% of Australian single mothers were not in the labour force and 3% were unemployed in 2021.

Figure 2.9. Employment rates are especially low for single mothers

Note: Employment rates are for women with at least one child aged 0-14.

Source: OECD Family Database.

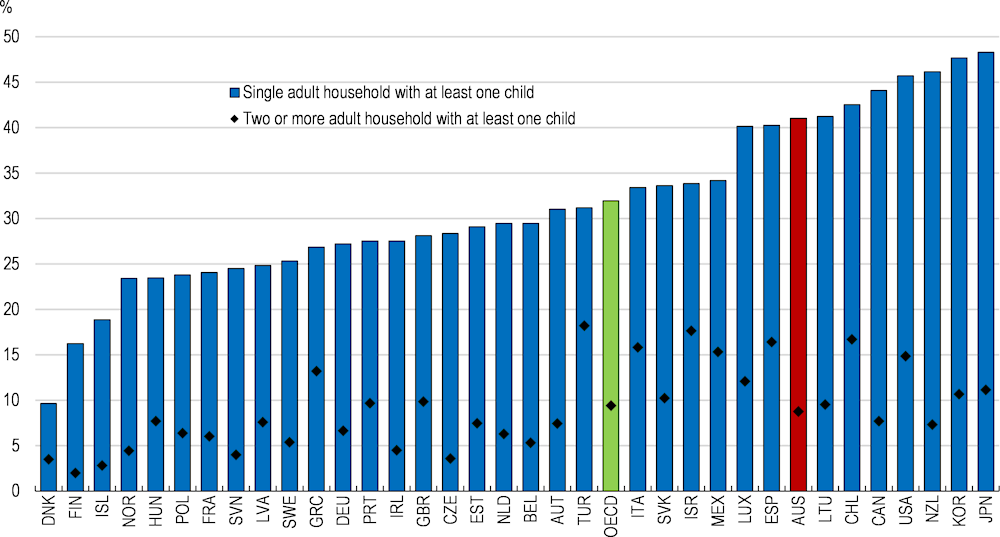

Many of those single mothers who are not in employment experience poverty. Pooling across waves of the HILDA Survey, about 45% of single mothers who were not employed found themselves in relative poverty (based on an evolving 50% of median disposable income poverty line). The poverty rate for single parents is high in Australia compared with other OECD countries () and around 80% of single parents in Australia are mothers. There is also a larger than average gap in Australia between the poverty rate of coupled and single parents than elsewhere (Figure 2.10). Analysis of data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics for 2017 highlighted that 37% of people in single parent families where the main earner was female lived in poverty compared with 13.6% living in poverty in the population overall. HILDA data suggest that the poverty rate for single mothers has remained broadly stable between 2017 and 2021.

Figure 2.10. Poverty rates are very high in single parent households

Relative income poverty rates, individuals in working age households with at least one child, by household type

Note: Data are based on equivalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The poverty threshold is set at 50% of median disposable income in each country. Working-age adults are defined as 18-64 year-olds. Children are defined as 0-17 year-olds. Data refer to 2018 for all countries except Canada, Latvia, Sweden and the United Kingdom (2019); Chile, Denmark, Iceland and the United States (2017); Netherlands (2016); New Zealand (2014).

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database.

Gender gaps in hours worked

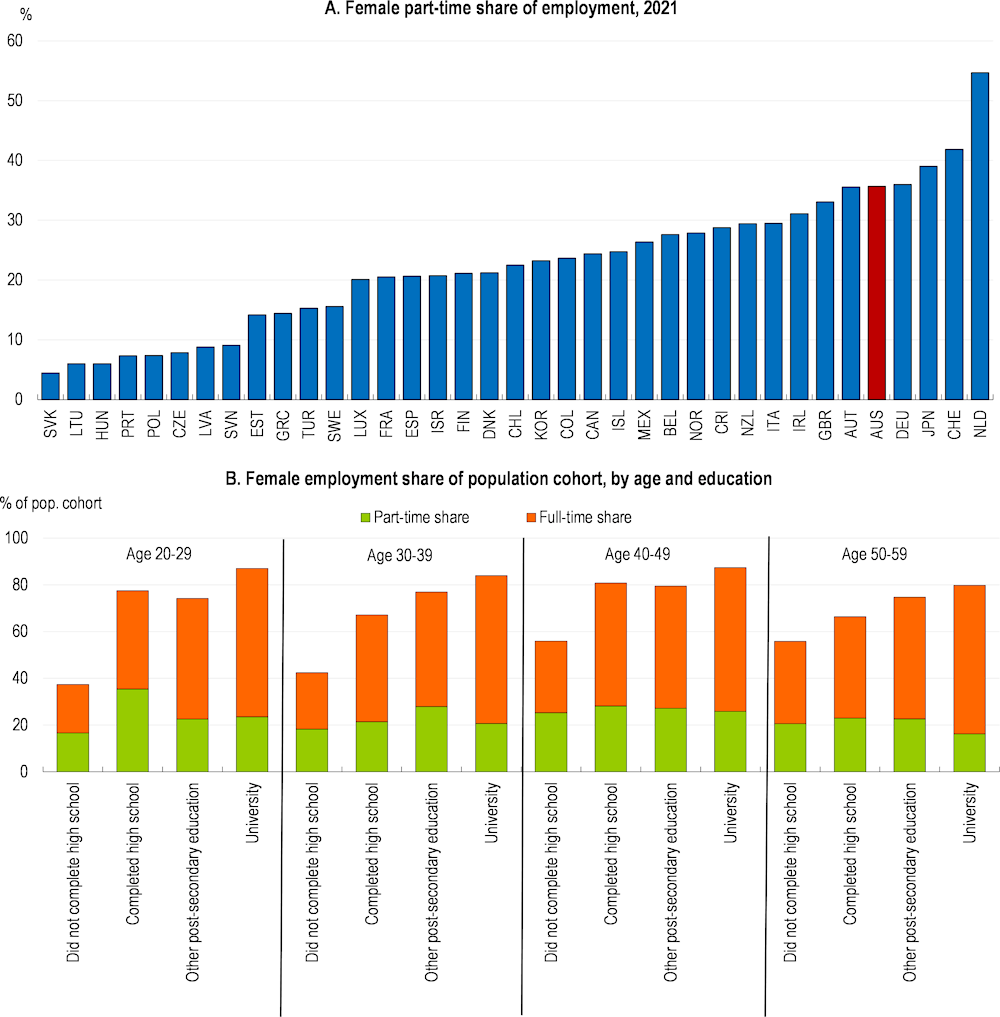

Many women in Australia who are employed work shorter hours than their male counterparts. While only 10% fewer women than men are in employment, they contribute 40% less hours worked. This reflects many women working part-time. Over one third of Australian women who are currently employed work less than 30 hours per week, a high proportion by OECD standards (Figure 2.11, Panel A). While this partly reflects a high proportion of part-time work in Australia (for both men and women) relative to other OECD countries, the gap between the share of women and men employed part-time is high by OECD standards. There tends to be a higher share of women undertaking part-time work in worker cohorts that have lower education levels (Figure 2.11, Panel B).

Figure 2.11. Many women in Australia work part-time

Note: Part-time employment is defined as people in employment (whether employees or self-employed) who usually work less than 30 hours per week in their main job. Panel A is calculated for those aged over 15.

Source: OECD Labour Market Statistics, HILDA, OECD calculations.

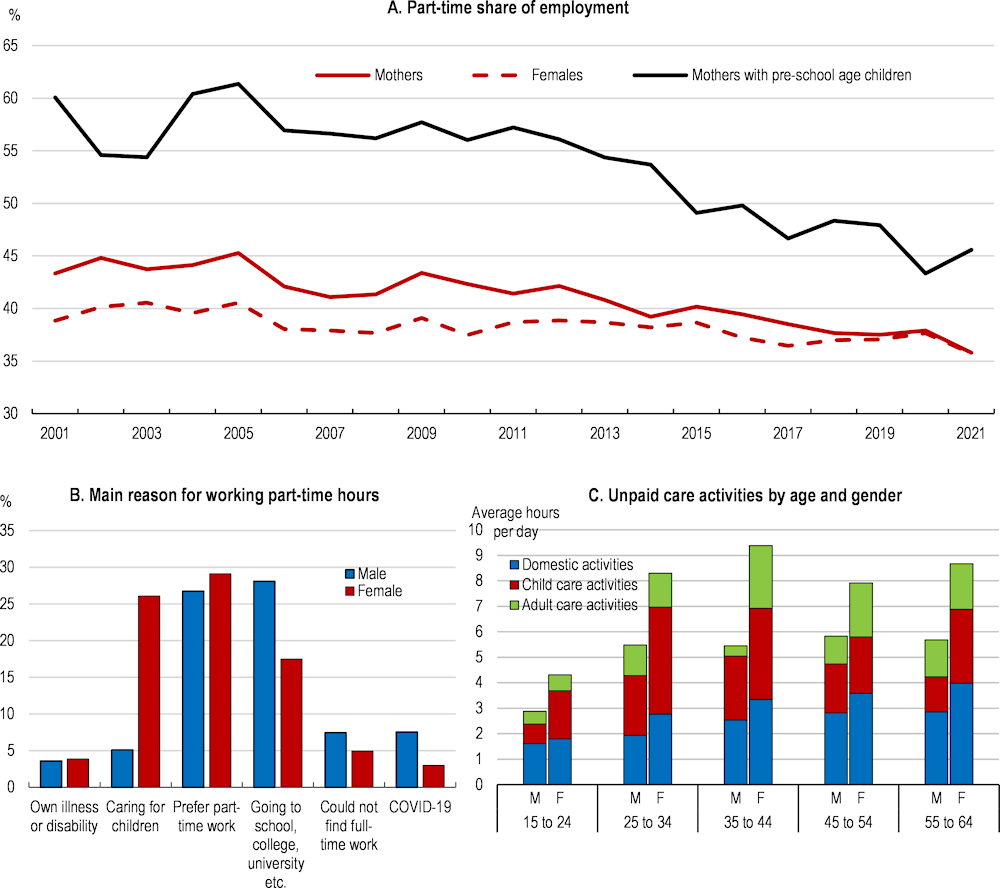

The incidence of part-time work is higher for mothers with children at pre-school age (Figure 2.12, Panel A). When asked in the HILDA Survey for the reasons for working-part time, around one quarter of women cite caring for children compared with 5% of men (Figure 2.12, Panel B). Even so, the part-time share for mothers with pre-school age children has declined by around 10 percentage points over the past decade. For mothers with children of any age, the part-time employment share had converged to that of women without children by 2021. This suggests flexibility in the system in that mothers increase their take-up of full-time work once their children are at school age, a feature that is less apparent in some other high income OECD countries such as Germany, Netherlands and Switzerland.

The lower participation rate of mothers (highlighted earlier in Figure 2.7, Panel C) and the high part-time share of mothers with young children reflects women being much more likely to reduce engagement in the labour market after childbirth. Bahar et. al. (2022) estimate a 55% decline in female earnings following the arrival of children that is the combined result of a sharp drop in hours worked and employment rate. At the same time, that study showed little discernable impact on the earnings of men once they became fathers. This accords with time use surveys that show that women undertake a higher share of care activities (Figure 2.12, Panel C). This is both the case for child and adult care activities. The gender gap in unpaid care work is high in Australia compared with other OECD countries (OECD, 2021a). In addition, women in Australia are much less satisfied than men with the division of housework and childcare tasks (Wilkins and Lass, 2018).

Figure 2.12. Childcare is a significant reason for women working part-time

Note: Part-time employment is defined as people in employment (whether employees or self-employed) who usually work less than 30 hours per week in their main job.

Source: ABS, HILDA, OECD calculations.

Gender gaps in wages

A full-time female worker earns around 13% less than her male counterparts on average. The gap narrowed over the past decade, but progress has slowed (Figure 2.13, Panel B). At median earnings, the gender wage gap is slightly below the average across OECD countries (Figure 2.13, Panel A). Gender differences in hourly wages are most pronounced for workers with higher levels of education (Figure 2.13, Panel C) and those in the highest income quintile (Figure 2.13, Panel D).

Figure 2.13. The narrowing in the gender wage gap has slowed

Note: In Panel A, the gender wage gap is defined as the difference between median wages of full-time male and female employees relative to the median wage of males. In Panel B, the gender wage gap is based on full-time adult ordinary time earnings.

Source: ABS, HILDA, OECD.

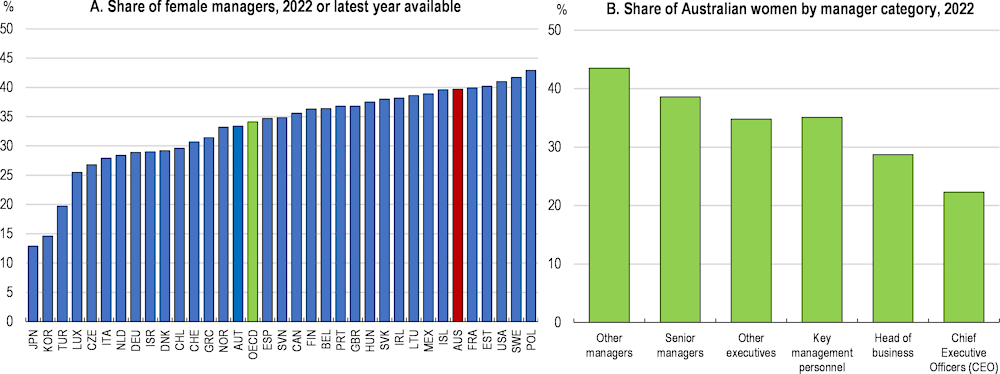

Gender wage gaps often reflect the same firm paying men more than women despite having similar skills (OECD, 2021b). This is mainly due to differences in tasks and responsibilities rather than differences in pay for work of equal value. While Australia has a high share of female managers compared with other OECD countries (Figure 2.14, Panel A), there is still a significant gap with the proportion of males in managerial positions. Gaps become more pronounced at higher levels of managerial seniority (Figure 2.14, Panel B). For instance, less than one in four Australian Chief Executive Officers are women.

Figure 2.14. Women are still underrepresented at the most senior ranks

Note: In Panel A, data for Australia are for 2021, but for most other countries they are for 2022, with the exception of Canada, Israel and Turkey (2021) and the United Kingdom (2019).

Source: OECD, Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

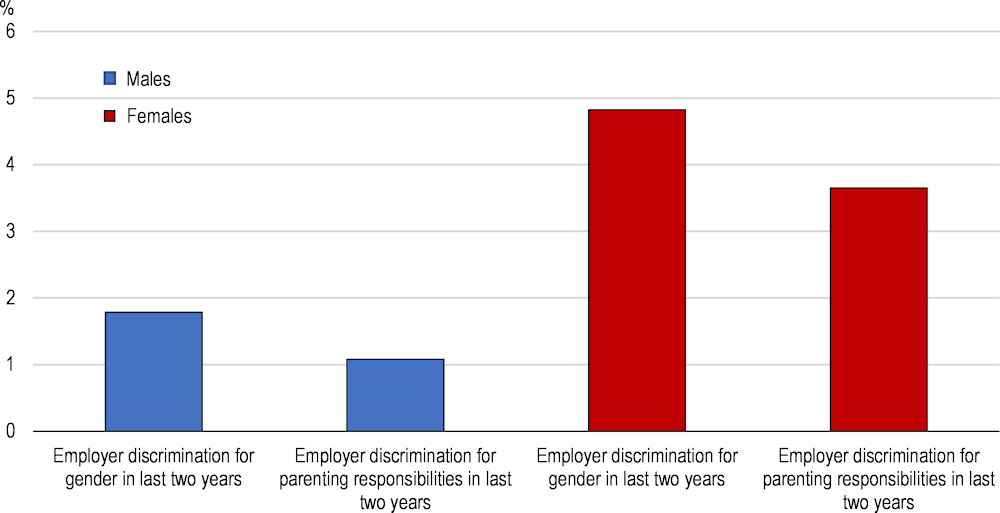

Figure 2.15. Women are more likely to experience discrimination by employers

Share experiencing discrimination in the last two years, by gender, 2018

Discrimination can also lead to within-firm gender wage gaps. Women in Australia report notably higher levels of gender-based discrimination by employers than men. According to successive waves of the HILDA Survey, around 8% of females reported employer discrimination in the past two years related to either their gender or parenting responsibilities, compared with less than 3% of men (Figure 2.15). Nonetheless, estimates based on microdata suggest that it has played less of a role in Australia than in many other OECD countries (Box 2.2).

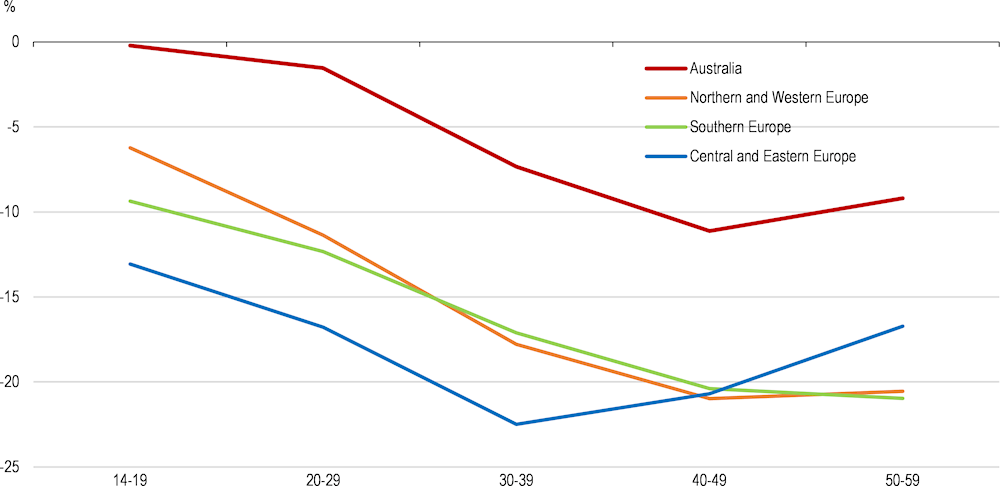

Box 2.2. Decomposing Australia’s gender wage gap using HILDA

Following the work of Ciminelli et. al. (2021) for 25 European countries, a gender wage gap decomposition is undertaken for Australia using HILDA data. This approach draws out the drivers of the gender wage gap based on how it evolves through the life cycle.

The focus is on the gender gap in hourly earnings between women and men with similar levels of educational attainment and labour market experience, and on three deep drivers that have been emphasised in previous research.

Compensating wage differentials – women may take up jobs with lower wages but with specific non-wage characteristics, such as higher working time flexibility or shorter commuting times, that allow them to spend more time in unpaid home work.

Slower human capital accumulation – female career paths may not allow them to accumulate human capital at the same rate as men. This may be because they interrupt their careers after childbirth, spend less time at the workplace than their male peers or forego promotions.

Gender discrimination – employers discriminate against women because of conscious or unconscious biases, or because they perceive the average woman to be less productive than the average man.

Figure 2.16. The gender wage gap increases over the life cycle

Estimated difference in hourly earnings (women-men)

Note: Regressions control for educational attainment and tenure in the firm and include dummy variables for apprentices, casual workers, as well as a cohort dummy that enters the estimating equation independently and as an interaction with the female dummy in order to control for cohort effects in wages and the gender wage gap.

Source: OECD.

The results for Australia highlight that the gender wage gap is very small for those in younger age brackets, when controlling for level of educational attainment and other labour market factors such as tenure in firm and whether the individual is an apprentice or casual worker (Figure 2.16). This contrasts with the aggregate results for European countries, which have a larger estimated gender wage gap in the earlier age groups. Assuming factors related to having children play a more limited role in explaining wage gaps in the youngest cohorts, the results suggest that other factors such as gender discrimination play a greater role in explaining gender wage gaps in these other countries than in Australia. The widening of the gender wage gap in Australia through the life cycle (in the 30-39 and 40-49 age groups) suggests that the child penalty plays a more important role in explaining the aggregate gender wage gap in Australia, through compensating wage differentials and slower human capital accumulation of women.

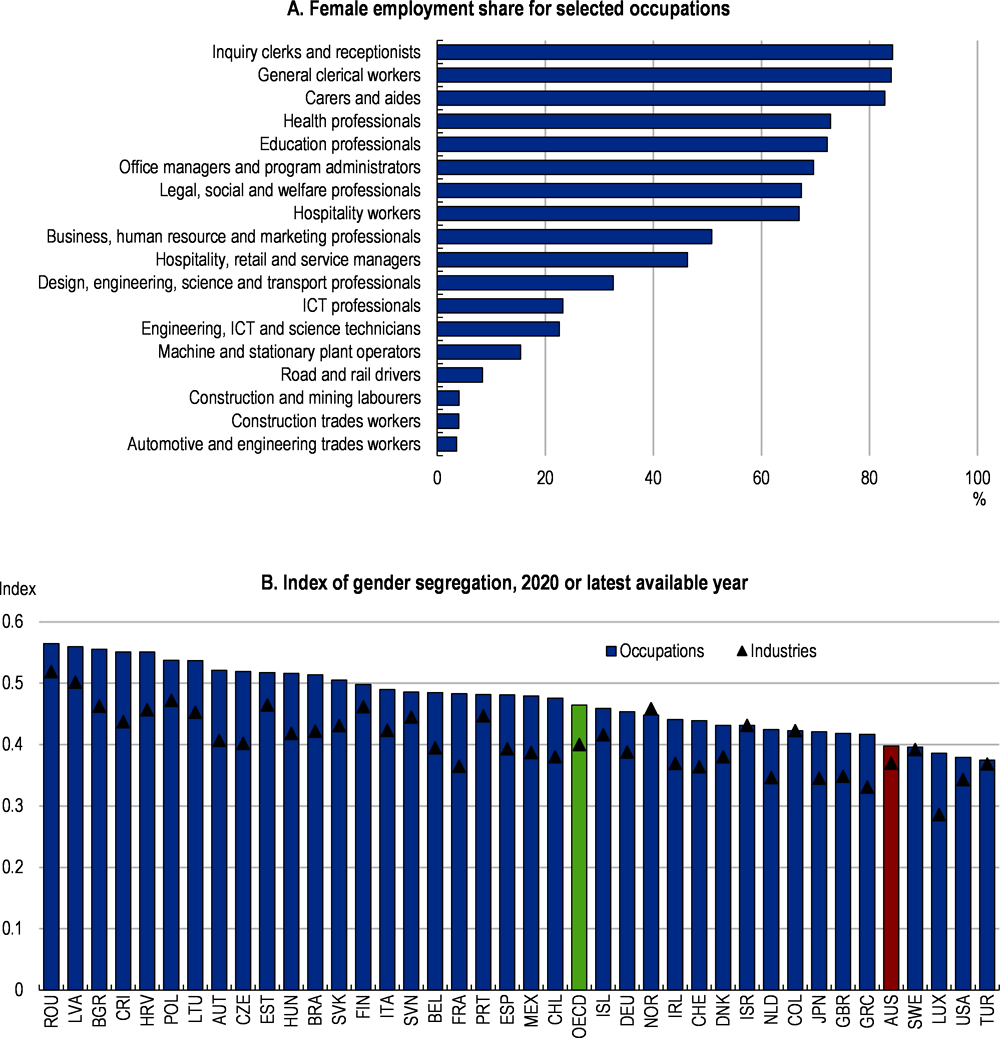

Figure 2.17. Gender segregation is apparent across occupations and industries

Note: In Panel B, the index of dissimilarity, or Duncan index, measures the sum of the absolute difference in the distribution of female and male employment across occupations or industries. It assumes that segregation implies a different distribution of women and men across occupations/industries: the less equal the distribution, the higher the level of segregation. It ranges from 0 to 1, from the lowest to the highest level of segregation. Here it was calculated using the ISCO-08 classification of occupations and the ISIC-4 classification of industries, both at 2-digit levels. For Australia, data refer to the previous ISCO-88 classification of occupations and the ISIC-3 classification of industries. For Israel and Italy, data refer to 2017. For the United Kingdom, data refer to 2019.

Source: ABS, OECD (2023c).

Large gender wage gaps are spread across occupations. Of the 87 occupations reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in May 2021, 60% had a per hour gender wage gap for full-time non-managerial employees exceeding 5%. It may be that women accept jobs within a given occupation that have lower wages in return for the non-monetary benefits of flexible working arrangements, allowing them to spend more time in unpaid home work (Ciminelli et. al. 2022). Consistent with this, gender wage gaps in Australia tend to be largest in those occupations that have a high share of inflexible and demanding jobs (Sobeck, 2022). Men are disproportionately employed in these occupations and the women who do work in them tend to opt for the more flexible jobs and work fewer hours per week.

Gender segregation in employment can add to wage gaps through men and women sorting across industries and occupations. More flexible work arrangements or societal norms may steer women towards certain professions with lower pay. For example, women account for over 80% of clerical workers and carers and aides, but less than one quarter of workers in engineering, ICT and science (Figure 2.17, Panel A). Risse (2023) estimates that male-concentrated occupations in Australia are associated with 6.5% higher wages and male-concentrated industries with 3.1% higher wages. One indicator of gender segregation across industries and occupations, the Duncan Dissimilarity Index, suggests that segregation is relatively low in Australia compared with other OECD countries (Figure 2.17, Panel B). Nonetheless, based on these results, around 40% of Australian workers would need to change occupations and industries to achieve perfect gender integration (meaning the share of women in each industry or occupation would mimic the share in total employment).

Policies to improve gender equality

A range of policies, including taxation, childcare, labour market policies and education can contribute to narrowing gender inequalities. This can be through reducing barriers to female employment, allowing men to take on more caring responsibilities and helping to breakdown gender norms. Mainstreaming considerations of gender impacts into all policy fields would help (Box 2.3). This includes expanding the scope of gender impact assessments to cover all new policy and budget proposals with a significant impact on gender equality. In addition, there is a need for robust evaluation into the effectiveness of existing policies on achieving stated gender goals.

Box 2.3. OECD Review of Gender Mainstreaming and Budgeting in Australia

The Australian government recently tasked the OECD Public Governance Directorate to undertake a Review of Gender Mainstreaming and Budgeting in Australia. The Review assesses the institutional structures in place and the recent work that has been undertaken to introduce gender impact assessments and gender budgeting as tools to support better-targeted policy and budget decisions.

The Review identifies six key actions to boost Australia’s efforts to improve gender equality:

Ensuring that gender impact assessment and gender budgeting have legal foundations so that the practices are sustained over time.

Establishing a Gender Budgeting Steering Group to guide and oversee gender budgeting efforts.

Enhancing the quality of gender analysis to ensure that it has the necessary impact on policies.

Building institutional capacity to broaden and deepen the understanding of gender equality issues across the Australian Public Service.

Developing a Gender Data Action Plan to strengthen the availability, awareness and analysis of gender-disaggregated data collected by the government.

Strengthening the Office for Women to better reflect the government’s heightened commitment to gender equality and ensure that the Office has the capacity to deliver required reforms.

Source: OECD (2023a).

The tax and transfer system

The tax and transfer system does not differentiate tax provisions based on gender as an explicit criterion. However, the system may affect men and women differently as it interacts with prevailing differences in underlying economic characteristics and behaviours. Given scope for increasing both women’s participation in the Australian labour market and the number of hours that women tend to work, the role of labour taxation and transfers in influencing the employment decisions are particularly relevant.

Reducing marginal effective tax rates

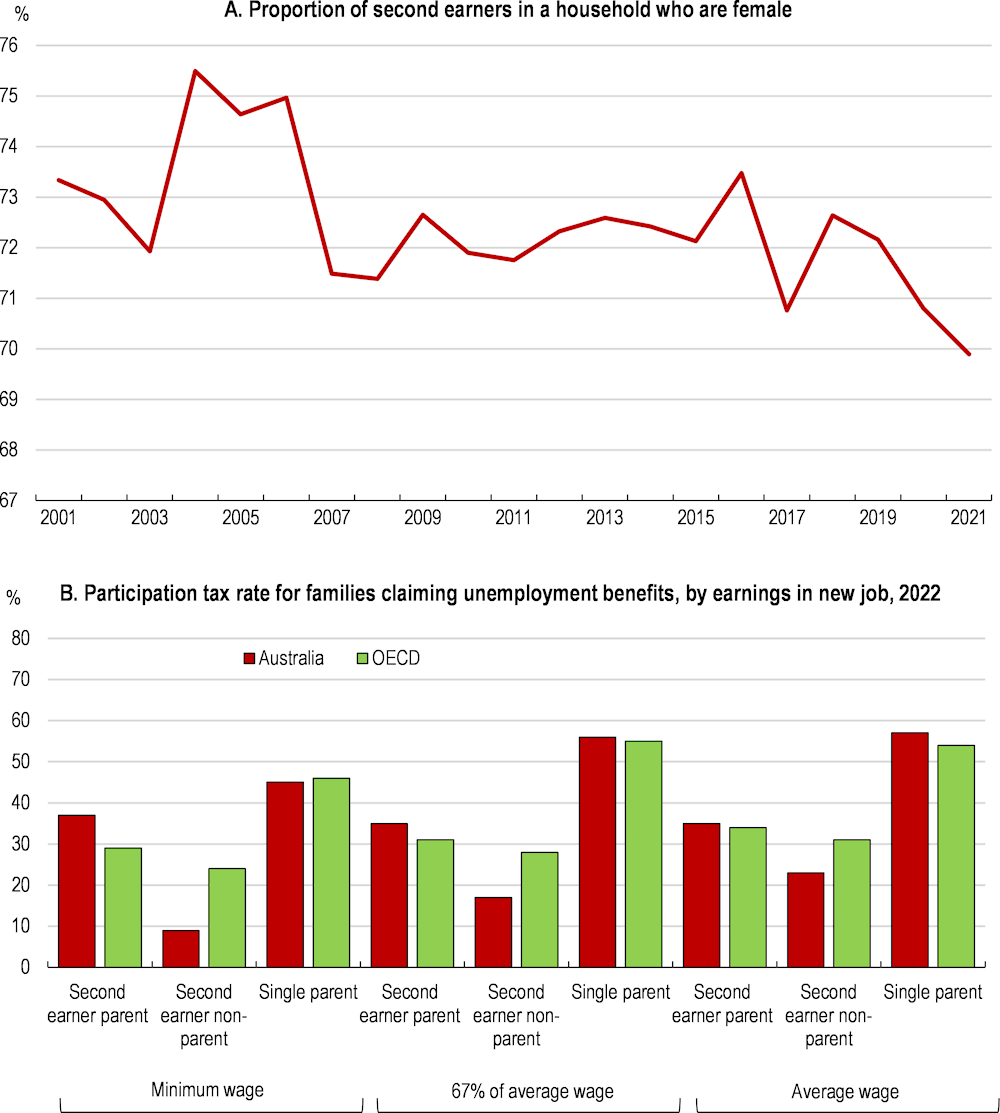

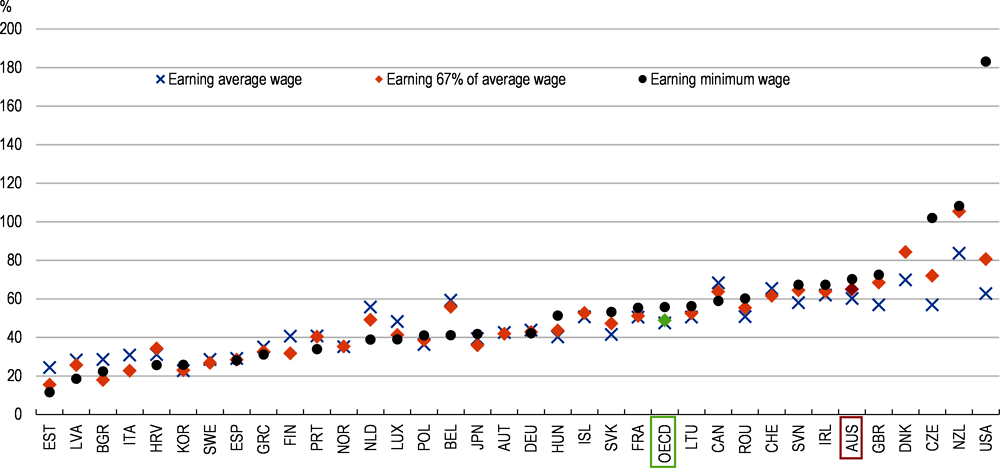

Figure 2.18. Second earners in a household are usually female

Note: In Panel B, the partner in the couple is assumed to earn the average wage. The calculations are for families receiving unemployment benefits and include social assistance and housing benefits. This calculation does not include childcare costs.

Source: HILDA, OECD Tax and Benefits Model, OECD calculations.

Australia has a highly progressive income tax schedule, which reduces aggregate gender inequality in post-tax earnings because women tend to be at the lower end of the wage distribution. The system of income taxation is based on individual rather than household income, meaning that second earners in a household have access to the tax-free threshold when moving into work or increasing hours. This helps the participation of women in lower paid and part-time work, given that around 70% of second earners in Australian households are female (Figure 2.18, Panel A). Participation tax rates for a women in a family currently receiving minimum income benefits are mostly around OECD average level, though they are comparatively low for second earners without children (Figure 2.18, Panel B).

On the benefits side, most payments are means tested and taper as earnings rise. There is the capacity to earn modest weekly labour income (for example, AUD150 per fortnight for unemployment benefits) before benefits begin to taper and a system of working credits for those transitioning from earning no income to becoming wage earners. Above the income free area, unemployment benefits taper at a rate of 50 cents for each additional dollar earned, increasing to 60 cents beyond a threshold. Parents have access to a parenting payment (the benefit taper on Parenting Payment Single is 40 cents for each additional dollar earned, but higher for a member of a couple) and two types of family tax benefits (Table 2.1). In contrast to the tax system, benefit eligibility depends on household income rather than just individual income. This means a female second earner entering employment or increasing hours worked can lose access to benefits relatively quickly depending on the income of their partner. There are no “in-work benefit” schemes, whereby workers with low wages can receive income supports and eligibility is conditional on being employed. Such schemes are used in many other OECD countries to support low-earners in work and these can be designed so that supports are tapered out gradually as people increase their working hours, providing better incentives to work (OECD, 2023b).

Table 2.1. Main Australian government benefit payments

|

Benefit name |

Eligibility |

Factors impacting payment |

Other characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenting Payment |

Principal carer of a dependent child aged under six for partnered recipients or aged under eight for single recipients. |

Dependent on partnered status and subject to personal and partner income testing. An assets test also applies. |

|

|

Family Tax Benefit Part A |

Families with care of a child aged under 16 and secondary students aged 16 to 19 years. |

Subject to an income test on family income. Payment taper at a rate of 20 cents per each additional dollar earned above an income free area, increasing to 30 cents per each additional dollar beyond a threshold. |

Paid per child |

|

Family Tax Benefit Part B |

Single parents and carers with care of a child up to 18 years old and some couple families with one main income and care of a child up to 13 years (18 years if a grandparent). |

Primary and secondary earners’ income must be below certain thresholds. |

Paid per family |

|

Carer Payment |

For people providing constant care for someone who has a disability, a severe medical condition or is frail aged. |

Can engage in employment or study for up to 25 hours per week and remain eligible. |

|

|

JobSeeker Payment |

Paid to unemployed people aged 22 or over and under eligibility age for the Age pension. |

Must satisfy mutual obligation requirements of actively seeking work or undertaking an activity to improve their employment prospect. Rates of payment are dependent on age, partnered status and presence of dependent children. |

A non-contributory benefit that is paid at a flat rate not time limited. |

|

Disability Support Payment |

Claimant must meet eligibility criteria around the diagnosis, treatment and stabilisation of their condition. They must also be unable to work for at least 15 hours per week within the next 2 years because of the impairment. |

Subject to income and asset test. Once on the payment, a recipient may work up to 29 hours per week before the payment is suspended. |

|

|

Youth Allowance (other) |

Paid to unemployed people aged 16 to 21. |

In addition to age, partnered status and presence of dependent children, payments also depend whether they live with and/or are dependent on parents. |

|

|

Commonwealth Rent Assistance |

A person must be eligible for a primary benefit such as JobSeeker, Youth Allowance, Family Tax Benefit Part A, or income support supplements. |

The maximum rates and minimum rent thresholds vary according to a person’s family situation, i.e. single or couple and the number of children they have and, for singles without children, whether accommodation is shared with other adults. |

Paid at the rate of 75 cents for every dollar of rent paid above the specified minimum rent threshold until the maximum rate is reached. |

|

Age Pension |

Means tested on income and assets. In addition to an income free area, there is a work bonus allowing pensioners to earn up to AUD250 per fortnight. |

Payable from age 65 and six months for men and women. |

Flat rate payment funded through general taxation revenue. |

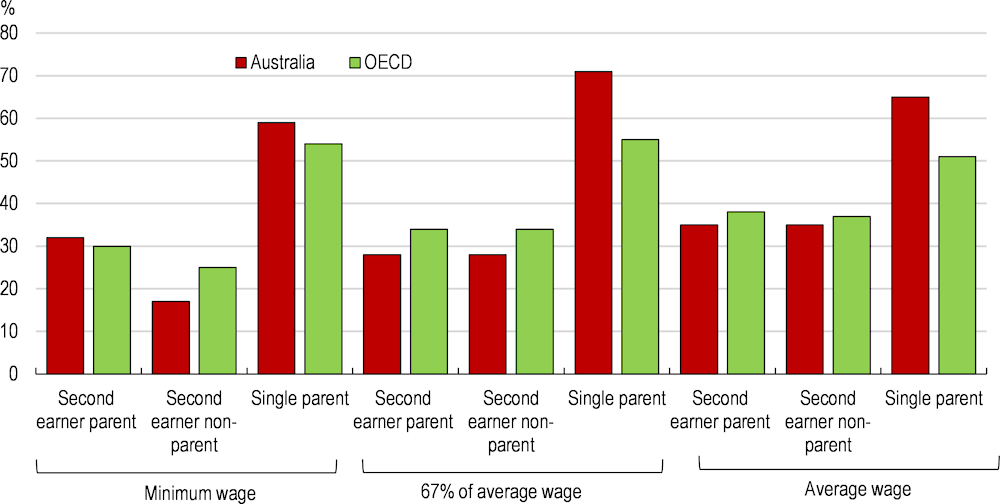

Benefit tapering contributes to high marginal effective tax rates on increasing work hours for some households (Figure 2.19). The effective tax rates when moving from 50% to 100% of full-time working hours are especially high for single parents, as they are more likely to receive benefits when working which are withdrawn as incomes rise. The calculations do not consider the additional effect of childcare costs when increasing work, though these create additional barriers (discussed further below). The high marginal effective tax rates of increasing work hours for some women is consistent with Australia having a relatively high share of females working part-time.

Figure 2.19. The tax and transfer system imposes very high marginal effective tax rates on single parents

Effective tax rate on increasing working hours, individual with two children at different wage rates, 2022

Note: The tax rates are based on increasing work hours from 50% to 100%. For the couple, the partner is assumed to earn the average wage. The calculations include social assistance benefits and housing benefits. This calculation does not include childcare costs.

Source: OECD Tax and Benefits Model.

The authorities could reduce marginal effective tax rates on additional hours through a slower tapering of benefits. For example, the sudden loss of Family Tax Benefit Part A end of year supplement when family income reaches AUD80,000 could be made more gradual. While this would entail a fiscal cost, it could be partly financed by removing the Family Tax Benefit B for couple families. At present, a couple family must have a second earner with income below AUD6,497 per year to receive the full rate of Family Tax Benefit Part B and income below AUD32,303 per year (with a youngest child aged 0 to 4 years) to attract an income test reduced rate of payment. While Family Tax Benefit B partly aims to compensate single earner families for paying more tax than a two-earner family (as the latter has access to two tax free thresholds), the income test raises disincentives to work for second earners. In addition, the authorities could consider other opportunities to reduce disincentives to work in the tax-transfer system, for instance combining Family Tax Benefit Part A and Family Tax Benefit Part B to avoid the stacking of withdrawal rates and reduce complexity in the system (Commonwealth of Australia, 2010).

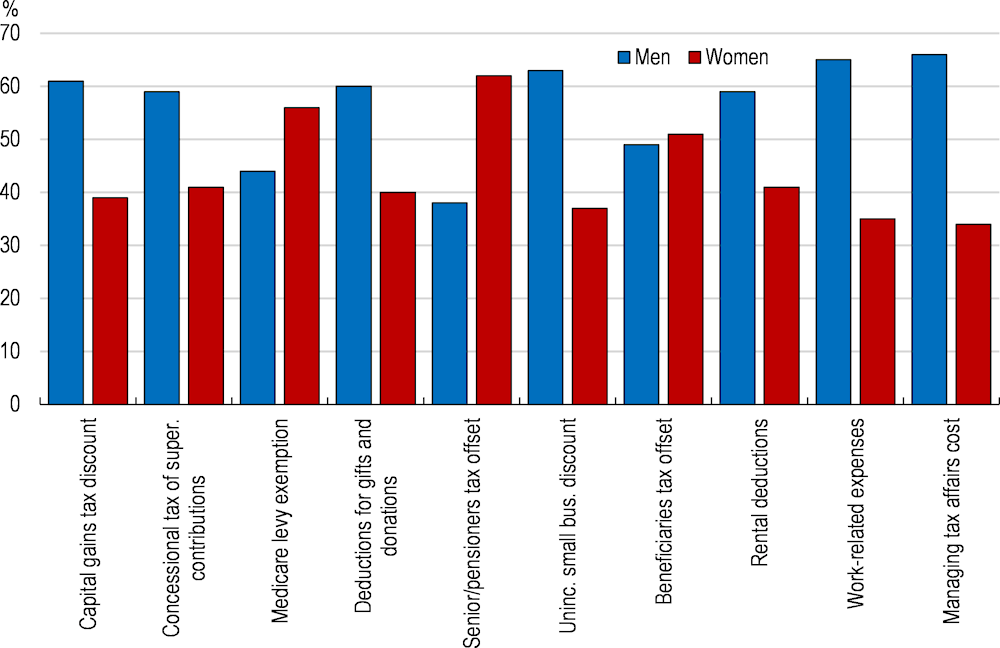

There are other ways the tax system impacts upon gender equality by having distinct effects on the incomes of women and men. For example, women receive a lower share of the benefits from many government tax expenditures (Figure 2.20). The economic justification for some of these expenditures is contested irrespective of the impact on gender inequality. For example, the generous private pension tax concessions in Australia may displace other forms of saving (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020) and the size of the capital gains tax discount may exceed that needed to compensate investors for inflation (OECD, 2021c). The government recently reintroduced gender impact assessment for selected budget measures and gender analysis for all proposals, but there is scope for this to be undertaken on a broader range of proposed measures in a more systematic way. As recommended by the upcoming OECD Review of Gender Mainstreaming and Budgeting in Australia, providing a legal basis for gender impact assessment and gender budgeting would benefit this aim (Box 2.3).

Figure 2.20. Women receive a lower share of the benefits from many tax expenditures

Share of tax expenditure received by gender, 2019-20

Providing adequate income support to Australian women

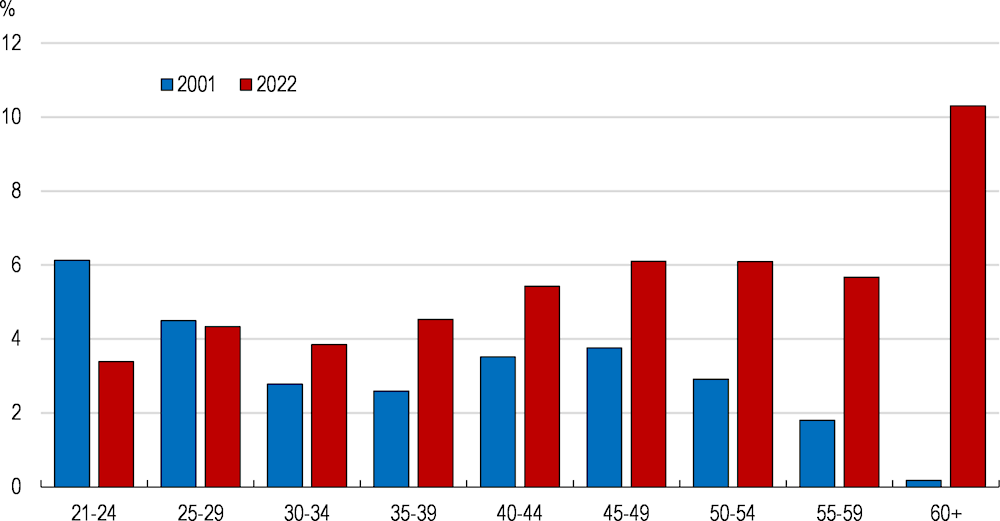

Government payments also have an important role in ensuring a minimum level of income for some women in Australia. For example, most recipients of carer payments and parenting payments are women. They have also become increasingly likely to be recipients of JobSeeker, which is Australia’s working-age unemployment benefit. While women accounted for around 30% of JobSeeker recipients in 2000, the share had risen to roughly 50% by 2022. In particular, older women now account for a significant share of these payments (Figure 2.21). The rising share of female recipients partly reflects the increased labour market participation of females. However, it is also due to an increase in the Age Pension qualifying age and changes in other income support payments (i.e. parenting payments, partner payments, partner allowance and wife pension) that have caused more women to move onto JobSeeker.

Figure 2.21. Women now account for a much larger share of JobSeeker recipients

Female share of total JobSeeker payment recipients by age group

As discussed in the last OECD Economic Survey of Australia (OECD, 2021c), the replacement rate of Jobseeker payments is very low compared with unemployment benefits in other OECD countries. This is partly due to JobSeeker being an unlimited payment that is funded through general taxation rather than a contribution-based unemployment insurance programme like in many other OECD countries. Recent analysis found that consumption spending drops by over 10% when an individual moves onto JobSeeker (Clarke et. al. 2023). The Australian government established an Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee in December 2022, which found JobSeeker payments to be inadequate, whether measured relative to the National Minimum Wage, pensions or a range of income poverty measures (Interim Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee, 2023). In response, the government announced a modest increase in the base rate for JobSeeker and other working age and student payments of AUD40 per fortnight and extended eligibility for the existing higher single JobSeeker payment rate to those in the 55-60 age bracket. There was also a 15% increase in the maximum rate of Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Nonetheless, minimum income benefits in Australia remain well below the relative poverty line of 50% of the median wage.

The government also recently expanded the Parenting Payment for single parents. This will mean that single mothers who are unemployed will be able to stay on the payment until their youngest qualifying child turns 14 (rather than 8) before being moved onto the less-generous JobSeeker payment. Given the high poverty risk of single mothers discussed earlier, such measures that provide adequate income support are important. There are unlikely to be discernible disincentive effects from providing this more generous support, as the parenting payment remains markedly lower than the minimum wage and is withdrawn at a slower rate than JobSeeker payments for non-principal carers.

Institutional arrangements to support the incomes of separated parents

Single mothers are often impacted by Australia’s child support scheme arrangements, whereby separated parents are required to provide financial support to help with the costs of raising children. Receipt of these payments has been shown to reduce the poverty rate in Australian single mother households by over 20% (Skinner et. al. 2017). However, unpaid liabilities under the scheme have been increasing, with most of those liabilities not subject to a payment plan (Interim Economic Inclusion Advisory Committee, 2023). While the authorities have made efforts to reclaim unpaid debts, through measures such as issuing Departure Prohibition Bans (i.e. travel bans) on individuals with an unpaid liability, further measures may be needed.

There are a variety of approaches taken to non-payment of child support across OECD countries. Salary deductions, seizure of assets and bank accounts, withholding of other public support payments and, in some countries, imprisonment, are all used elsewhere (Miho and Thévenon, 2020). In many jurisdictions, the government or another responsible authority provides a backstop for child support. For example, the Estonian Family Benefits Act in 2016 introduced a provision whereby child supports were paid by the government if a non-custodial parent does not fulfil their payment obligations. The government will then claim back the support from the debtor parent, with the potential use of administrative measures such as rescinding a driving license or restricting entrepreneurial support. Given that pursuing non-payment through the courts can be costly for a custodial parent, considering a greater role for the government in guaranteeing payments should be considered in Australia. At the same time, continued supports that help non-custodial parents to be self-sufficient are important. For instance, providing employment and social supports conditional on the payment of child support can reduce the risk of non-payment (Miho and Thévenon, 2020).

Retirement incomes of single mothers can also be threatened when divorce settlement decisions do not include superannuation (private pension) assets (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). In 2018, the government announced that the Australian Taxation Office would provide accurate and timely superannuation data to courts to increase the visibility of superannuation assets in family law proceedings. The establishment of this directive in the April 2022 Visibility of Superannuation Law is welcome.

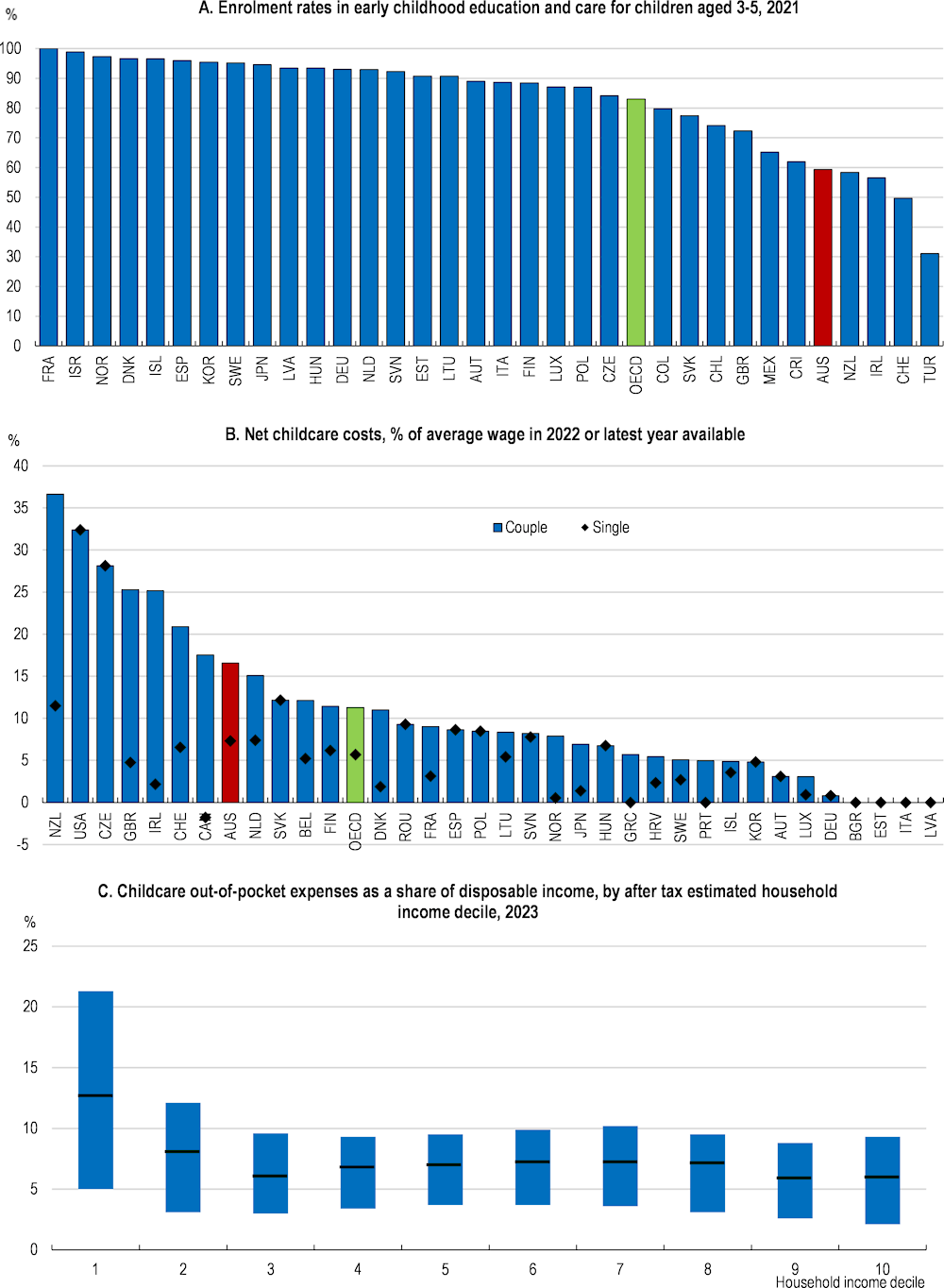

Supporting affordable childcare

Ability to access high quality and affordable childcare makes it easier for parents to return to work after childbirth and provides the option for both to take on full-time work. However, enrolment rates in early childhood education and care are slightly below most OECD countries. This is due to a low share of 3-5 year olds being enrolled in childcare compared with elsewhere in the OECD (Figure 2.22, Panel A). The availability of childcare can be an impediment to accessing childcare, a recent study found 35% of the Australian population live in childcare deserts (Hurley et. al., 2022), but cost is also a key factor. Out-of-pocket childcare costs for a couple are high relative to most other OECD countries, constituting over 15% of the average wage (Figure 2.22, Panel C).

Figure 2.22. Low childcare enrolment rates partly reflect high out-of-pocket childcare costs

Note: In Panel B, estimates are based on either a couple or single earning 67% of the average wage. Net childcare cost are equal to gross fees less childcare benefits/rebates and tax deductions, plus any resulting changes in other taxes and benefits following the use of childcare. Calculations are for full-time care in a typical childcare centre for a two-child family (children aged 2 and 3), where both parents are in full-time employment and the children are aged two and three. Full-time care is defined as care for at least 40 hours per week. For couples, both parents earn 67% of the average wage. In countries where local authorities regulate childcare fees, childcare settings for a specific municipality or region are modelled. For more details see the OECD Tax-Benefit model methodology. In Panel C, each box represents the middle 50% of households in each income decile. The median is represented by the black line.

Source: OECD Family Database, OECD Tax-Benefit data portal, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

The high cost of childcare adds significantly to the work disincentives for second earners. The OECD Faces of Joblessness project identified high disincentive rates as a barrier to employment for over one third of Australian mothers with care responsibilities (Immervoll, et. al., 2019). Australia has a largely market-based early childhood care system, with the government providing a subsidy for approved childcare that decreases as family income rises. The subsidy is subject to an activity test, with the hours of subsidised childcare increasing with the hours of activity (defined as work, education, starting a business, volunteering and actively looking for work). Overlaying out-of-pocket childcare costs on the impacts from the tax and transfer system highlights that 65% of additional earnings are lost for a second earner taking a job that pays 67% of the average wage, rising to 70% for someone taking a job at the minimum wage (Figure 2.23). This, along with problems meeting the activity test, may be a factor behind the low participation rates of some women in Australia, especially those with low educational attainment. There are also large financial disincentives to second earners taking on the fifth day of work per week (Kennedy, 2022). This partly owes to the steep tapering of the government childcare subsidy as household incomes rise (Wood, 2020).

Figure 2.23. High childcare costs contribute to a high disincentive rate for second earners

Per cent of earnings lost when entering employment and using childcare, 2022

Note: This indicator measures the percentage of earnings lost to either higher taxes or lower benefits when a parent of two children takes up full-time employment and uses centre-based childcare. Calculations refer to a couple with two children aged 2 and 3 where the other parent works full-time at 67% of the average wage.

Source: OECD.

Public funding for early childhood education and care has typically been lower than in other OECD countries. However, in response to high childcare costs, both Federal and some State governments have been increasing childcare subsidies. The Federal government has raised the maximum amount of the childcare subsidy from 85% to 90% and reduced the speed at which the subsidy is withdrawn as family incomes increase. The subsidy is based on a maximum hourly rate that the government subsidises, though over 20% of centre-based childcare services charged above this maximum rate in 2022 (Department of Education, 2023). Access to subsidised care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children has also recently been increased, through the provision of 36 hours of subsidy per fortnight regardless of their family’s income or activity level.

An important question is how to ensure that increased public subsidies translate into more affordable and available childcare. A risk in a market-based childcare system, such as Australia, is that weak government control over the fees charged to parents results in higher subsidies translating into higher childcare prices. At the same time, market-based systems can prove more agile, with an ability to quickly expand supply to meet demand (OECD, 2020). For example, a rapid expansion of childcare in Korea was built largely on growth in private services (OECD, 2019a). To investigate the market dynamics in the sector, the Australian government has commissioned inquiries by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) into childcare costs and the Productivity Commission into the childcare sector overall (reports are due in December 2023 and June 2024 respectively). If the ACCC inquiry concludes that prices for childcare have been increasing materially faster than provider costs, the government should consider enlisting the ACCC to actively monitor prices, costs and profits in the sector going forward.

One of the constraints to future childcare supply is retaining and growing the workforce. There has been high turnover, with a recent survey of educators finding that over one third did not intend to stay in the sector in the long-term (United Workers Union, 2021). The primary reasons for this were low pay, overwork and feeling undervalued. Job vacancy rates for early childhood teachers increased by 30% over the year to May 2023, with shortages most acute outside of major metropolitan areas (Department of Education, 2023). In collaboration with the childcare sector and other key stakeholders, Federal and State governments have published a ten-year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, 2021).

Improving pay and working conditions, including through providing better access to professional development and mentoring activities, will be key. Doing so would overwhelmingly benefit female workers, given they account for 97% of workers in the sector. At the same time, there is scope to streamline the application and approval process to attract overseas-trained childcare workers. At present, an application for a qualification levelling assessment needs to be made, from which point it takes several months before the applicant receives a response. There is also scope to attract more males to the occupation. While improving pay and conditions would be beneficial in this regard, there is also value in further working to break down gendered stereotypes relating to childcare work.

Faced with similar challenges around childcare resourcing, Germany has had the “More Men in Early Childhood Education and Care” programme since 2011. Initiatives include a series of programmes to promote childcare as a career option to school-age boys and the establishment of a coordination centre that provides a resource for men wanting a career change later in life (Hoenisch, 2016). Such career changes require further training, highlighting the need for established pathways into lifelong learning programmes for adults who want to move into the sector. The existing Recognition of Prior Learning programme in Australia is important in this regard. The programme recognises existing skills, knowledge and experience gained through working and prior learning, so that students looking to attain a vocational early childhood education and care qualification do not need to demonstrate the same competencies again during their course. Other OECD countries such as Denmark and Belgium have used marketing campaigns to foster the public image of male childcare workers (OECD, 2019b).

Flexible childcare offerings can also be important for allowing parents to integrate into the labour market. However, very few services currently offer childcare during non-standard hours: only 1.7% of services were offered after 6.30pm on weekdays and around 2% on weekends in 2022. In addition, services typically only offer session lengths of 10-12 hours (Department of Education, 2023) and parents are charged for the full session duration regardless of how many hours are attended. This has implications for parents wanting childcare on the fifth day of the week, given that the Child Care Subsidy generally subsidies costs for a maximum of 50 hours of weekly care.

Improving the parental leave system

Parental leave systems support mothers staying in work and labour market re-entry after childbirth. Well-designed parental policies can also help shape gender norms around childcare and contribute to reducing stereotypes that contribute to gender segregation in occupations and industries. This is especially relevant in the Australian context given the sustained decline in the female employment rate after childbirth. Decisions around childcare are an inherently personal one for a family. However, government parental leave policies can be designed so that they do not create barriers to gender equality in caring responsibilities. Fathers taking a more equal share of unpaid work can reduce the labour market dislocation women may experience after childbirth. At the same time, there is a relationship between the participation of fathers in early year childcare and the cognitive, emotional and physical outcomes of their children. Fathers who engage more with their children also tend to report greater life satisfaction and better physical and mental health than those who care for and interact less with their children (OECD, 2016b).

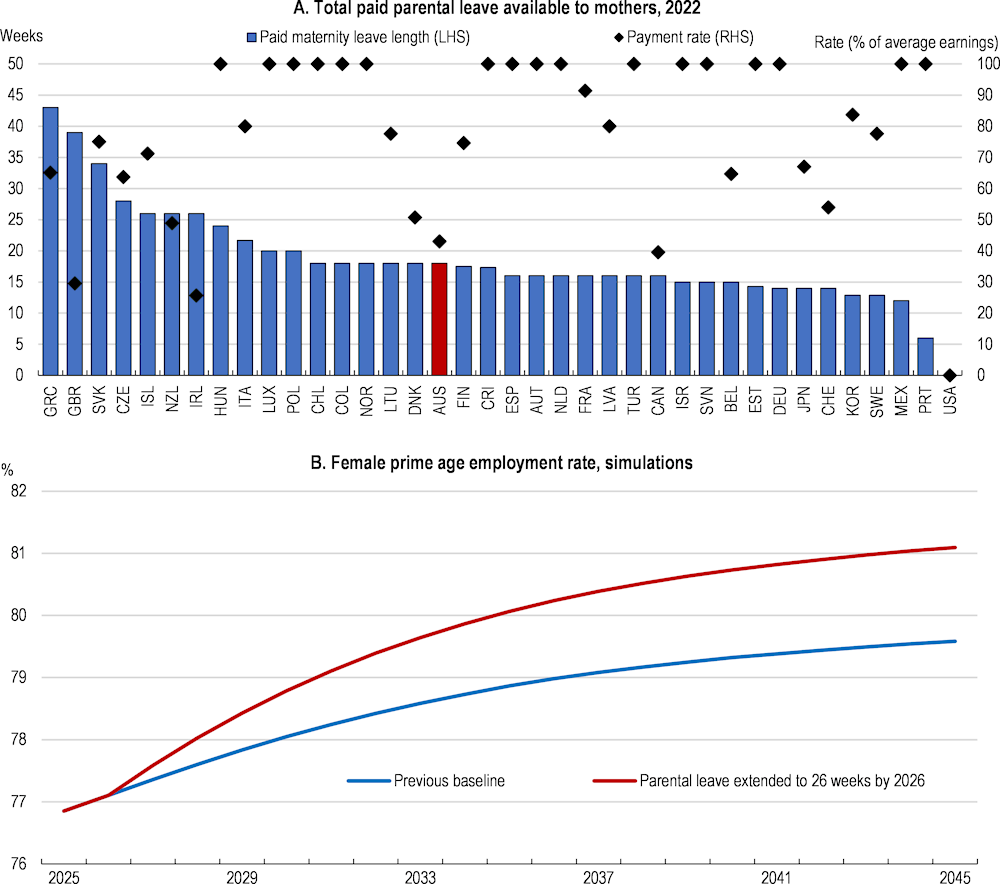

The public parental leave system in Australia is relatively young compared to systems in most other OECD countries, having first been introduced in 2011. Until recently, the scheme consisted of two payments; Parental Leave Pay (up to 18 weeks) and Dad and Partner Pay (up to 2 weeks), both paid at the rate of the national minimum wage. In addition, some employers offer extra parental leave: data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency suggest that 60% of large private companies (over 100 employees) offer some paid parental leave for primary carers on top of the government scheme. Compared to most other OECD countries, the duration of publicly provided leave and the rate at which it is paid is relatively low (Figure 2.24, Panel A). In July 2023, the two public payments were combined, meaning that partners can now claim up to 20 weeks paid parental leave between them. Single parents are eligible for the full 20 weeks. Increased flexibility is also being introduced, with parents able to receive Parental Leave Pay concurrently for up to 10 days and in blocks as small as one day at a time. The government plans to introduce further legislation to progressively increase the duration of the leave entitlement to 26 weeks in 2026. Simulations using the OECD Long-Term Model suggest that this would increase the female prime-age employment rate by 1¼ percentage points within 10 years (Figure 2.24, Panel B).

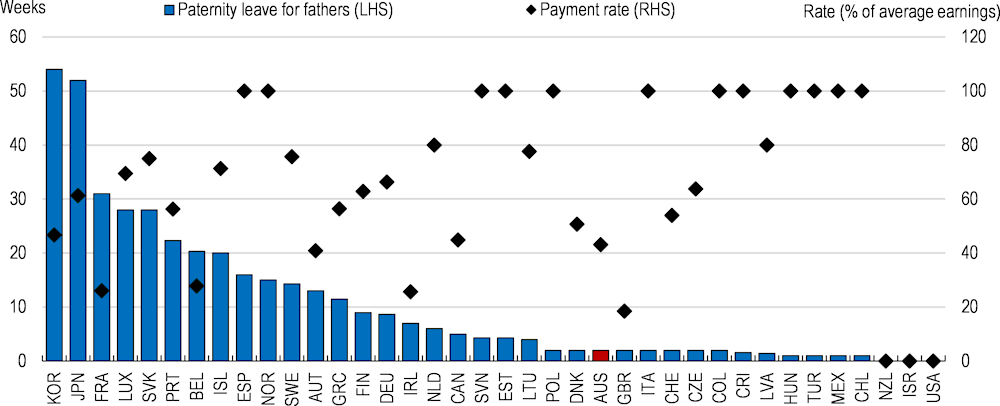

Providing parental leave specifically for fathers can help reduce the barriers to men undertaking a higher share of unpaid care work within the household. This ensures a father taking leave does not affect his partner’s entitlement and can help legitimise the idea of fathers taking parental leave. In Iceland and Sweden, such a quota led to a doubling in the number of parental leave days taken by men. Some OECD countries offer “bonus periods”, where a couple may qualify for some extra weeks of paid leave if the father uses a certain portion of sharable leave (OECD, 2023c). With recent changes, Australian fathers will be able to access government-funded Paid Parental Leave at the same time as that funded by employers. In 2021, less than 30% of new Australian fathers used publicly administered paternity leave, so further efforts are needed to promote take up. An ongoing barrier is that leave is paid at the minimum wage (Figure 2.25). This has also been a factor in low utilisation of parental leave by fathers in other OECD countries such as France, Japan and Korea, despite very generous entitlements in leave duration (OECD, 2016).

Figure 2.24. The duration and rate of leave for mothers is low

A balance is needed between the number of weeks of parental leave available and the rate at which it is paid. Past work suggests that the impact of maternity leave duration on female labour force participation tends to be positive but exhibits diminishing returns beyond a certain threshold (Thévenon and Solaz, 2012). Taking leave for longer than a year can impact adversely on future earnings prospects and make it more likely that people leave the labour force (OECD, 2016). Further investigation into the impacts of different designs of parental leave policy in the Australian context should help inform future policy changes. Further duration extensions of parental leave are likely needed in the Australian context, especially while challenges regarding affordable high-quality childcare persist. However, a focus also needs to be the rate at which public parental leave is paid and increasing the share of parental leave reserved specifically for fathers.

Figure 2.25. The duration and rate of father-specific parental leave is low

Paid paternity leave and paid father-specific parental and home care leave in weeks, 2022

Australia is one of the few OECD countries where contributions to private pensions stop during periods of maternity or paternity leave. This exacerbates gender inequality in retirement earnings given that parental leave is disproportionately taken by women. Employers can make voluntary contributions to private pensions and there is also a tax incentive for making contributions to a non-working or low-earning spouse. In other OECD countries, there are a variety of approaches taken to continuing pension contributions during the period of parental leave. In most countries, employees and employers keep contributing at the same rate during such periods. However, there are differences in the earnings base used to calculate contributions, with some countries using past earnings and others, such as Estonia, making contributions based on the minimum wage (OECD, 2021d). One approach could be for some mandatory cost sharing arrangement between the government and employers to pay private pension contributions during parental leave.

Skills policies that improve gender equality

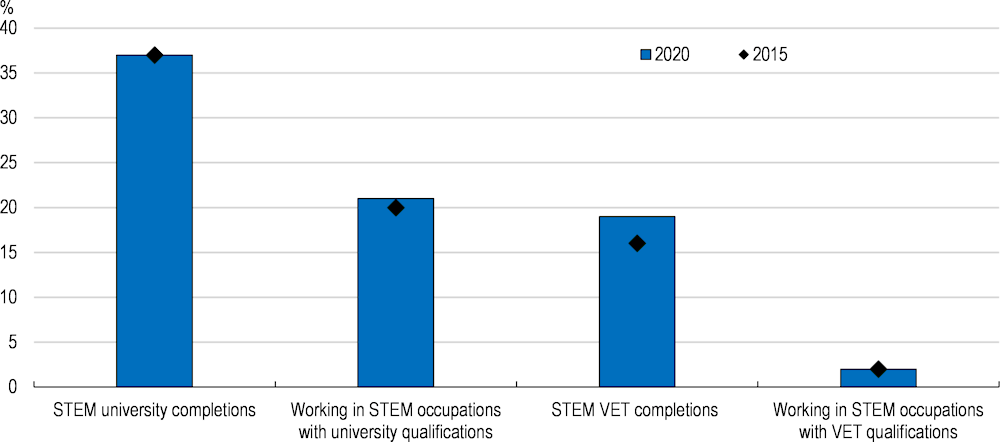

Women’s position in the labour market is influenced by the skills they learn in the education system. A lack of women studying STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and ICT (information and communication technologies) is likely to contribute to the gender pay gap, given many associated jobs are comparatively well paid. The skills learnt in these programmes are especially important for workers to benefit amid the ongoing digital and green transformations (OECD, 2019c). Among high-performing students in mathematics or science in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, one in three boys in Australia expect to work as an engineer or science professional at the age of 30, while only one in five girls expect to do so (OECD, 2019c). This translates into patterns in higher education and work: women accounted for 37% of completions of STEM university courses and only 21% of university graduates working in STEM occupations in 2020, with the proportions even lower for women in vocational education and training (VET) courses (Figure 2.26). These proportions have changed little in recent years. Similarly, the share of women studying and working in ICT has remained very low: just 3% of female tertiary education graduates had a degree in ICT compared with 12% of male graduates in 2020.

Figure 2.26. Relatively few women are studying and working in STEM fields

Share of women studying and working in STEM fields

Reducing the gender education gap in fields such as STEM and ICT requires society-wide changes, with parents, teachers and employers all becoming more aware of their own conscious or unconscious biases. Indeed, results from PISA highlight that parents are more likely to expect their sons rather than daughters to work in a STEM field (Schleicher, 2019). The fact that a significant proportion of female STEM graduates in Australia do not work in STEM occupations suggests government programmes that focus on promoting early work experience, apprenticeships and mentoring arrangements for women studying these disciplines need to be reviewed. Despite a variety of Federal Government programmes to encourage gender equality in STEM and ICT, some have noted the lack of a long-term strategy that is well-coordinated across the stages of education and employment and accompanied by a rigorous evaluation framework (CEDA, 2023). The government is currently undertaking a “Diversity in STEM” review that will make recommendations on how the government can support women, and other underrepresented groups, to participate in STEM education, careers and industries.

Adult education and training systems can also have an important impact on the employability and wages of women, especially in a context of rapidly changing skill needs. The OECD Survey of Adult Skills highlights that the gender gap in adult learning participation is modest in Australia, as in most other OECD countries. A focus on improving the engagement of women with low existing skill accumulation would seem beneficial given the low labour force participation rate and hours worked of this cohort. Nonetheless, low-qualified women tend to be less likely to participate in training than their male counterparts (OECD, 2023c). Family responsibilities and costs are identified as particular barriers. In response, policymakers should consider promoting short modular courses that provide learners with greater flexibility and have a strong emphasis on recognising prior learning. "Micro-credentials” are short courses that can be taken online and are recognised across training providers. These allow for individuals to tailor their learning programme and may also come with curriculums that are easier to adapt to the changing skill demands in the labour market.

The Federal Government is in the process of updating estimates of basic skills in Australian adults, with a view to providing new support measures. To alleviate barriers to female participation, consideration should be given to measures that reduce the impediments to an individual undertaking training. The government has already been active in introducing targeted apprenticeship support programmes for women seeking a career in trade occupations. As part of current negotiations on the National Skills Agreement with states and territories, women’s participation in skills acquisition and gender equality is one of the identified reform areas. Across OECD countries, the cost and availability of childcare is often a key impediment. While child care subsidies are available in Australia to individuals undertaking study to improve work skills, the traditionally high cost of care discussed earlier is likely to be a constraint.

Labour market laws

Work conditions can also play an important role in encouraging female labour force participation and ongoing skill development. Private enterprise has a key role in creating a supportive environment, but public policies that create complementary institutional structures and laws are fundamental.

Promoting workplace flexibility

Measures that promote workplace flexibility for both men and women can be important for promoting better sharing of domestic tasks and breaking down occupational and gender segregation (Goldin and Katz 2011). However, this is only the case if flexibility is available to both genders and workers are not penalised for pursuing them. Recent changes to industrial relations laws have provided further clarity around the process for an employee requesting flexible work arrangements and for disputing the refusal of a request. Such measures should create opportunities for those who desire more work flexibility if well implemented.

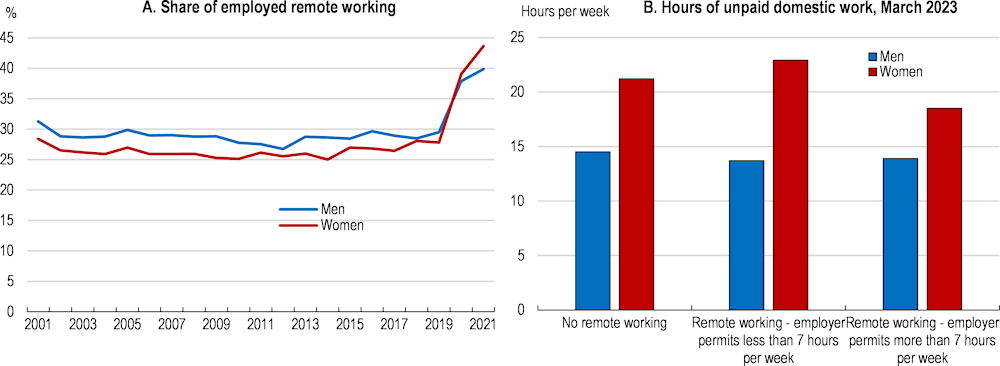

The pandemic was the catalyst for an increase in flexible work arrangements. The share of Australian firms promoting flexible work rose from 15% to 68% between 2017 and 2021 (Duncan, et. al., 2022). The increase in remote working was more pronounced for females than for males in Australia (Figure 2.27, Panel A). This same pattern across genders was observed in the United States and European Union (Touzet, 2023). Recent surveys suggest women have a stronger preference for remote working, and often work in occupations that are more conducive to it, both in Australia (Lass et. al., 2023) and elsewhere (Touzet, 2023). As well as improving the gender balance in domestic duties, remote working may promote female employment, given lower commute times tend to have a larger positive impact on female labour force participation (Farré et. al. 2020).

The risk is that a bigger increase by women in the take up of more flexible working amplifies the existing inequalities in unpaid work, impairs women’s career progression and compounds existing gender segregation in employment. Indeed, men whose employer permitted them to work from home in 2023 did not report any greater hours of unpaid domestic work per week than those who were not able to work remotely (Figure 2.27, Panel B). Some evidence suggests that a key to making more flexible work practices gender friendly is having other policies in place that breakdown prevailing gender norms. These include improved provision of childcare (Song and Gao, 2020) and more equal use of parental leave between mothers and fathers (Wanger and Zapf, 2021).

Figure 2.27. Remote working has increased more for women

Note: Panel B is based on employed respondents and unpaid domestic work includes grocery shopping, food preparation, laundry, grounds care and gardening, home and vehicle maintenance, caring for children, caring for an adult, paying bills.

Source: HILDA; Dahmann and Gupta (2023); OECD calculations.

Improving pay transparency

Gender pay inequalities are being tackled in Australia through reforms that increase pay transparency. Such measures have been recently pursued in other OECD countries, with the intention of supporting underpaid female workers negotiate up their wage by raising awareness of pay differences within firms. This may be particularly important for higher educated women in Australia, given that it is in this group where gender pay gaps are most apparent. Studies of pay transparency reforms in the UK (Blundell, 2021), Canada (Baker, et. al., 2021) and Denmark (Bennedsen, et. al., 2020) suggest pay transparency measures contribute to shrinking gender pay gaps, though in several cases this has been through slower pay increases for men than faster pay increases for women. Some evaluations suggest more modest benefits when enforcement mechanisms or wage gap visibility are weaker (Böheim and Gust, 2020; Gulyas et. al., 2020). Given such regulations impose administrative costs on firms, the Australian authorities should closely monitor the impact of new pay transparency laws on improving gender equality and adjust the provisions accordingly.

In 2022, the Federal government prohibited pay secrecy clauses in employment contracts. Then, earlier this year, introduced new legislation that requires firms with more than 100 employees to publicly report on a range of areas including gender pay gaps, gender composition of the workforce and governing bodies, conditions and practices related to flexible working arrangements for employees (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023b).

There are other types of pay transparency measures used that could potentially contribute to narrowing gender pay gaps. For example, the European Commission directive on pay transparency laws gives workers in all companies (not just those above a headcount threshold) the right to request information disaggregated by gender about the average pay level of workers doing a similar job. The directive also places the burden of proof in discrimination cases on employers and strict sanctions including fines and back pay for workers who experienced discrimination. Further encouraging the use of clear job classification systems (standardise pay and make it transparent across men and women within specific job categories) in both the public and private sectors can improve transparency around what is required for a promotion, which can contribute to more objective recruitment and promotion rounds. This can reduce discrimination and contribute to more women receiving promotions to better-paid roles and responsibilities within firms. Such measures can be complemented by targets and quotas to help address gender gaps in the short and medium term, but these are not a sustainable solution in themselves. The key to sustainable success is the development of a gender-balanced cohort of competent employees for promotions into senior positions within companies and across sectors.

Creating more women-friendly workplaces

Ensuring all workplaces are welcoming to females can encourage female participation, lower barriers to the efficient allocation of labour and reduce the gender segregation in occupation and industries. Policy measures that reduce workplace sexual harassment of women can help achieve these aims. A burgeoning international literature is highlighting the adverse economic impacts of sexual harassment. For example, Folke and Rickne (2022) use data from Sweden to show that women who reported harassment were 25% more likely to leave their job and tended to move to workplaces with a lower share of men and to earn less in their new post. Indeed, the survey results suggest that women are willing to give up 10% of their salaries to avoid harassment.

Reducing sexual harassment has recently been a priority for the Federal government. In November 2022, the government legislated the Anti-Discrimination and Human Rights Legislation (Respect at Work) Bill. This introduces a positive duty on employers to take steps to eliminate sexual harassment in the workplace, with the Australian Human Rights Commission enlisted to monitor and assess compliance. The Bill also allows the Australian Human Rights Commission to self-initiate an inquiry into unlawful discrimination and remove existing procedural barriers to a representative body (like a worker union) initiating a federal court action on behalf of the group. In addition, The Fair Work Act (which defines workplace rights) was amended in March 2023 to prohibit sexual harassment in connection with work, so that a person who experiences sexual harassment will be able to seek compensation and penalties through the Fair Work Commission.

A barrier to women pursuing sexual harassment claims is the cost risk associated with litigation. Since 2001, applicants have been ordered to pay the respondent’s costs in over half of cases where the applicant was unsuccessful and sometimes (around 10% of cases) even when the applicant was successful (Thornton, et. al. 2022). The government planned to introduce new arrangements whereby parties bear their own costs with the court retaining discretion to award costs. However, some advocates for sexual harassment claimants favour an “equal access” asymmetrical costs model. Such an approach would protect a complainant from an adverse costs order, unless they have acted vexatiously or unreasonably, but enable them to recover costs should they succeed. Under this approach, a respondent would not be able to recover their legal fees even if successful, which may impact legal practitioners’ ability to offer services on a conditional cost basis as it means that respondents would need to be certain they could cover their own costs (Commonwealth of Australia, 2023d). The government is currently consulting on the best approach to adopt.

Recommendations for fully realising the economic potential of women in Australia

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

RECOMMENDATIONS (Key recommendations in bold) |

|---|---|

|

Ensuring the tax and transfer system promotes gender equality |

|

|

The design of the tax system narrows gender income inequalities and results in low participation tax rates. However, steep benefit tapers are a barrier to some women moving from part-time to full-time work. |

Introduce a more gradual tapering of benefits as household earnings rise, potentially funded through removing Family Tax Benefit Part B for couple families. |

|

An increasing share of “JobSeeker” unemployment benefit recipients are now women, but the replacement rates are low. |

Further increase the rate for JobSeeker benefits and consider further options to reduce disincentives for recipients to increase working hours. |

|

Tax expenditures, such as the capital gains tax discount and on superannuation contributions, disproportionately benefit men. |

Provide legal underpinning for gender budgeting to strengthen gender impact assessment in the budget process. Undertake robust evaluation of the impact of existing policies that are aimed at improving gender equality. |

|

Unpaid liabilities under the Child Support Scheme have been increasing, with most of those liabilities not subject to a payment plan. |

Prioritise the timely and full payment of child support liabilities through the establishment of a government guarantee and by making the receipt of government payments such as social benefits conditional on the payment of child support. |

|

Reducing childcare costs and improving the parental leave system |

|

|

Net childcare costs are high and create a significant barrier to employment for women. Higher childcare subsidies could translate to higher prices with constraints on the availability of childcare workers. |

Improve access and affordability of high-quality childcare by encouraging the development of the private childcare sector and improving provision for non-standard hours of care. Undertake ongoing monitoring of prices, costs and profits in the childcare sector. Streamline the application and approval process to attract overseas-trained childcare workers. |

|

The payment rate of parental leave is relatively low, with low take-up by fathers. The authorities are planning to expand parental leave duration to 26 weeks in 2026. |

Along with extending public parental leave duration, prioritise raising the rate at which it is paid and increasing the share of parental leave reserved specifically for fathers. Introduce contributions to private pensions during periods of parental leave. |

|

Improving gender equality in the labour market |

|

|

New legislation improves pay transparency, through prohibiting pay secrecy clauses in employment contracts and requiring large firms to publicly report gender indicators. |

Closely monitor the impact of new pay transparency laws on reducing gender inequality and adjust the provisions accordingly. |

|

Women are underrepresented in information technology (ICT) and science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Men are also underrepresented in caring roles, such as nursing, teaching and child care. |

Implement effective programmes that focus on promoting early work experience, apprenticeships and mentoring arrangements for women studying STEM and ICT and men studying caring professions. |

References

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (2021), A ten-year strategy to ensure a sustainable, high-quality children’s education and care workforce 2022-2031, Education Services Australia.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2023), Childcare Inquiry, Interim Report, June 2023.

Australian Human Rights Commission (2022), Time For Respect: Fifth National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces, November 2022.

Bahar, E. et. al. (2023), “Children and the gender earnings gap: evidence for Australia”, Treasury Working Paper, No. 2023-02.

Baker, M. et. al. (2021), “Pay transparency and the gender gap”, NBER Working Paper, No. 25834.

Belkar, R. et. al. (2007), “Labour force participation and household debt”, Research Discussion Paper, No. 2007-05.

Bennedsen, M (2020), “Do firms respond to gender pay gap transparency”, NBER Working Paper, No. 25435.

Blundell, J. (2021), “Wage responses to gender pay gap reporting requirements”, Centre for Economic Performance, No. 1750.

Borland, J. (2022), “The persistence of occupational segregation in Australia”, Labour market snapshot, No. 94.

Burchell, et. al. (2014), “New method to understand occupational gender segregation in European labour markets”, European Commission, Directorate-General for Justice.

Broadway, B. et. al. (2022), From Partnered to Single: Financial Security Over a Lifetime, Breaking Down Barriers, June 2022.

CEDA (2023), Occupational Gender Segregation, Committee for Economic Development of Australia.

Churchill, B. and L. Craig (2022), “Men’s and women’s changing attitudes towards fatherhood and working fathers in Australia”, Current Sociology, Vol. 70, No. 6.