Steep rises in energy and commodity prices and disruptions in gas and oil markets linked to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine triggered a cost-of-living crisis and created a risk of energy shortages. Lower global growth, supply chain bottlenecks and higher uncertainty dampened activity and economic prospects. Monetary policy has been tightened to counter inflationary pressures and should remain tight. Supportive fiscal policy helped preserve jobs and incomes but has weakened a strong fiscal position. Pressures linked to population ageing call for structural measures to improve fiscal sustainability. The labour market has performed well but faces chronic labour and skills shortages. Making employment easier for mothers can help in this regard. Raising skills would boost productivity, which still lags behind the OECD average. The Czech economy remains highly energy intensive, relies heavily on coal and records high greenhouse gas emissions. The current energy crisis is an opportunity to strengthen the resolve to reach climate commitments.

OECD Economic Surveys: Czech Republic 2023

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

Introduction

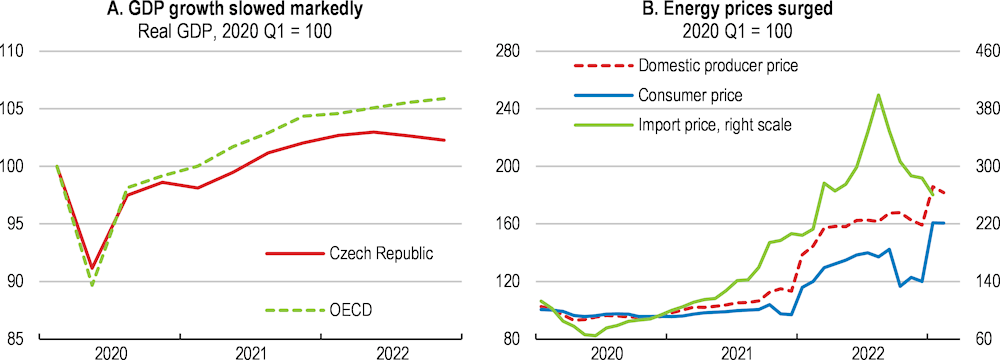

The Czech economy was on track to recover from the COVID-19 crisis when, in early 2022, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine brought new challenges. Steep rises in energy and commodity prices (Figure 1.1) and supply disruptions in gas and oil imports from Russia triggered a cost-of-living crisis and created a risk of energy shortages. Lower global growth, persistent constraints in global supply chains and higher uncertainty dampened activity. To counter steep and broadening inflationary pressures, and rising inflation expectations, the central bank raised policy interest rates in a timely way, tightening financing conditions. GDP growth slowed markedly (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Russia’s war against Ukraine brought new challenges

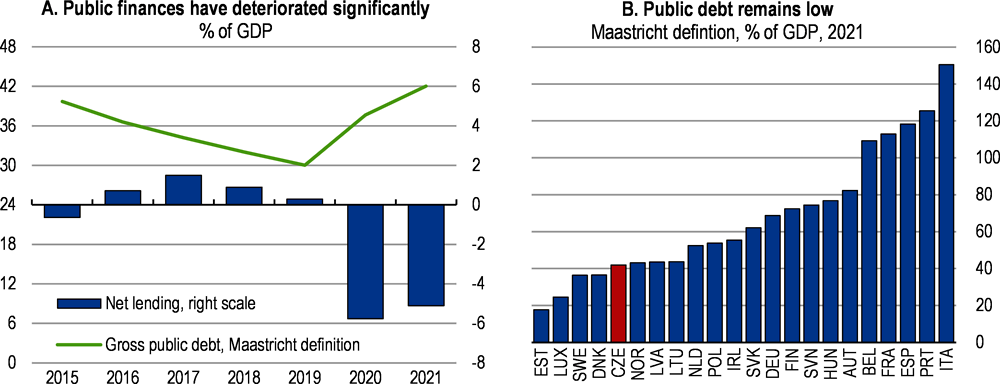

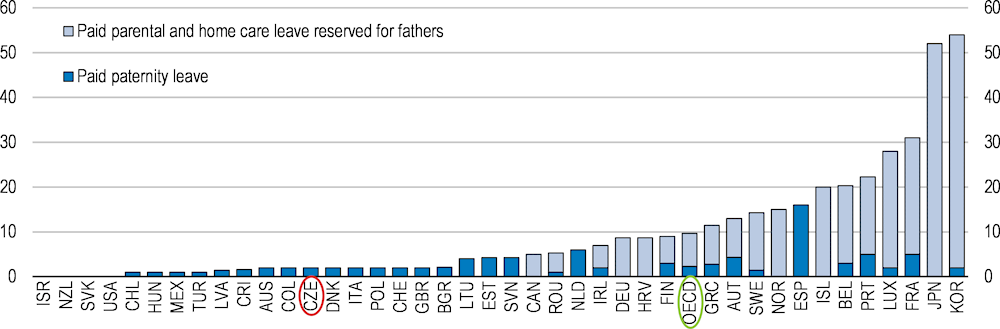

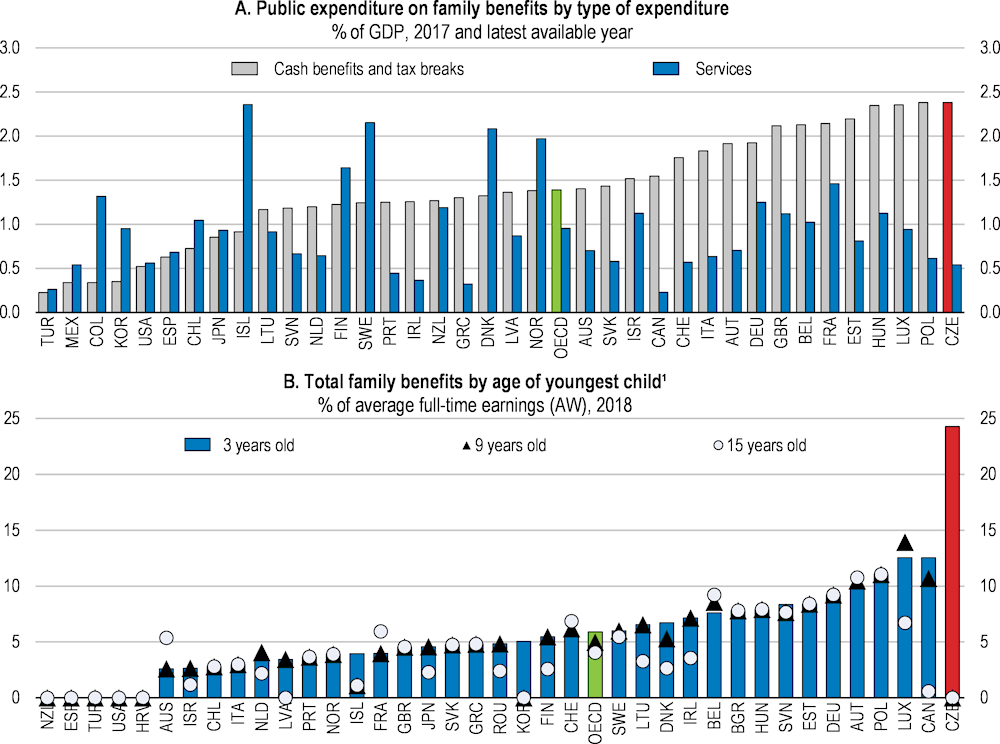

Loose fiscal policy during the pandemic, measures to cushion the impact of high energy prices and unresolved structural issues linked with population ageing have worsened fiscal sustainability. The expansionary fiscal policy helped preserve jobs and incomes, but has led to a large deficit (Figure 1.2) and increased public debt. Several tax cuts have aggravated the structural budget balance and untargeted cash transfers to families with children and pensioners have continued (see Box 1.1). The Czech Republic has welcomed a large number of Ukrainian refugees. Yet, expenditures to cover the cost of basic services and income support to the refugees, together with commitments to increase defence spending add to the fiscal pressures. High core inflation, an overheated labour market and relatively high growth in household incomes over 2020-21 indicate that the accommodative overall macroeconomic policy stance contributed to domestic inflationary pressures. Monetary policy tightening started early, but fiscal policy has yet to initiate a firm consolidation path.

Figure 1.2. Fiscal sustainability pressures have increased

Note: In Panel B youth are shown in green, 25-64 year-olds in blue and seniors in orange. After 2021 data are from the “medium variant” of UN scenarios.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database; United Nations (2022), World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision, Online Edition.

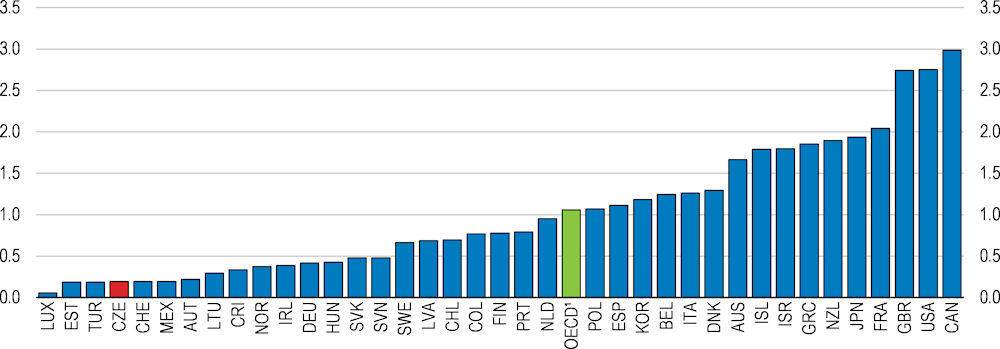

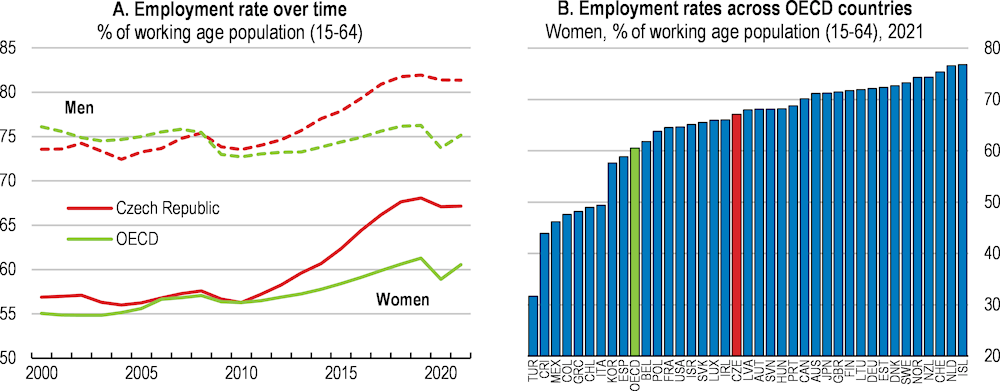

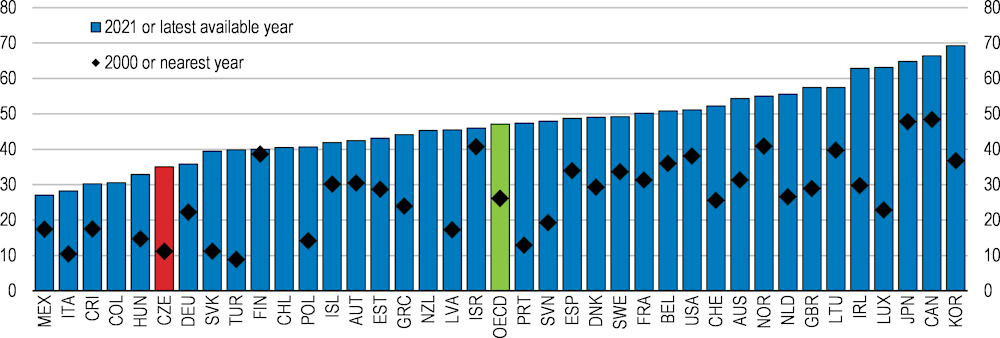

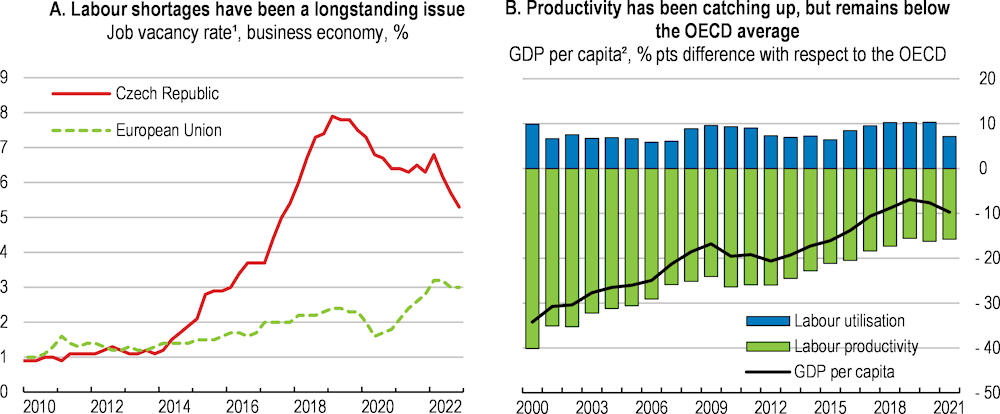

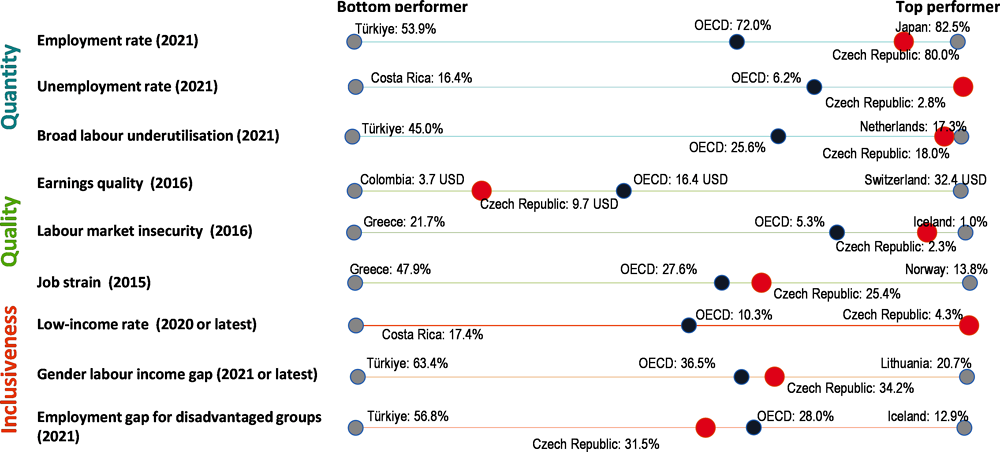

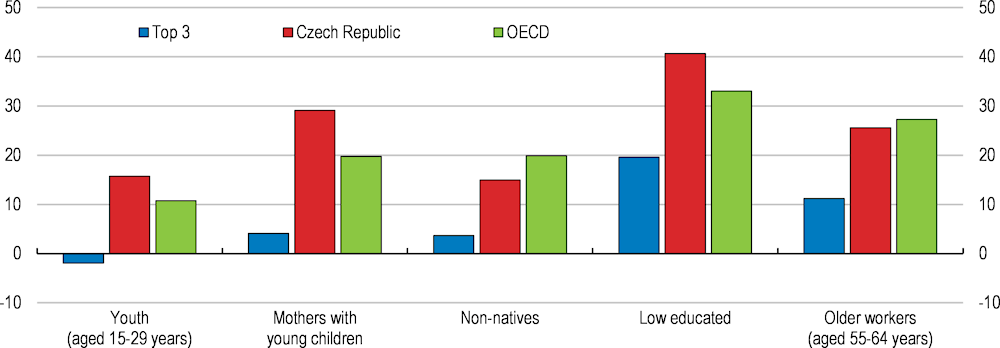

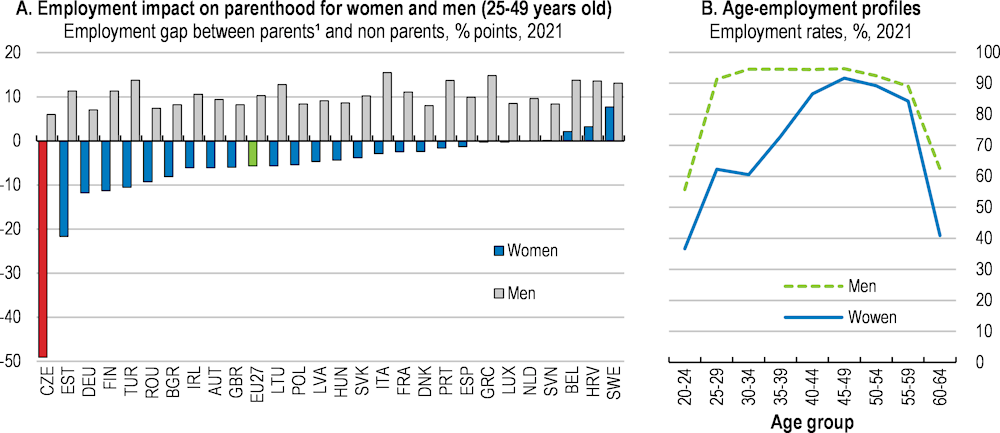

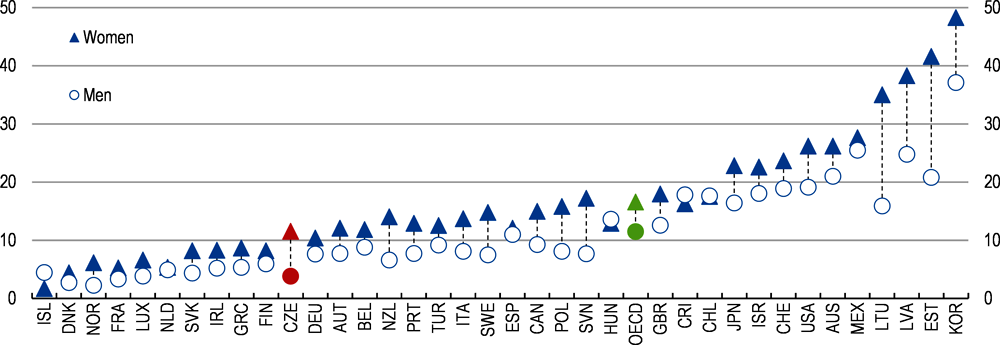

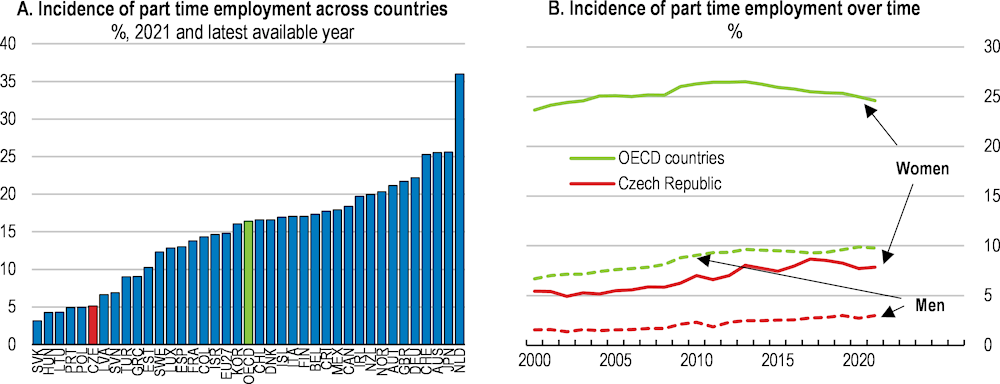

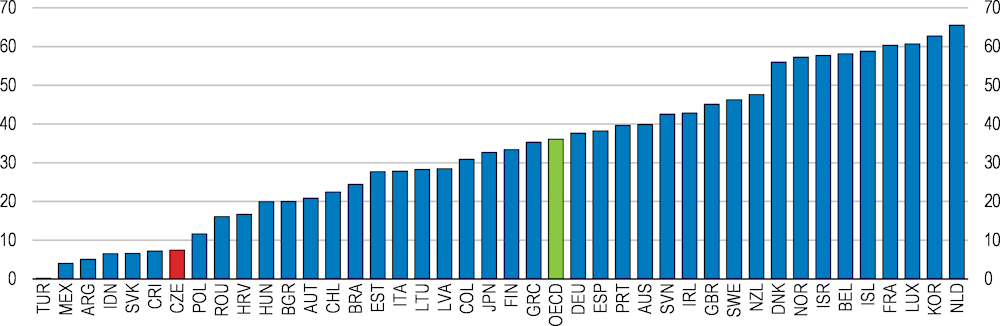

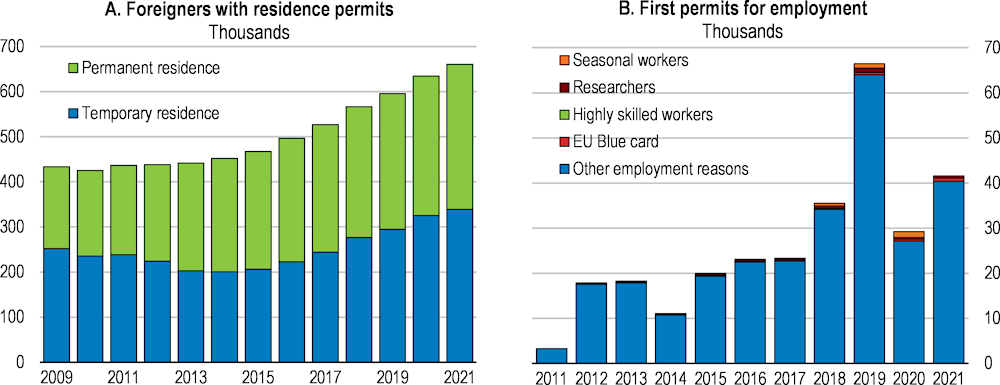

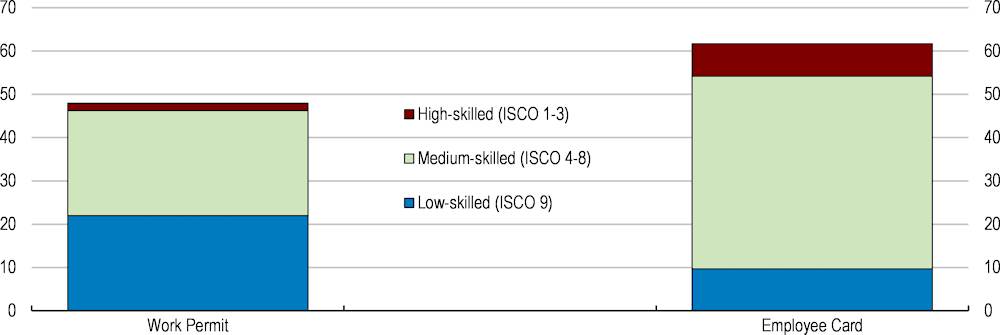

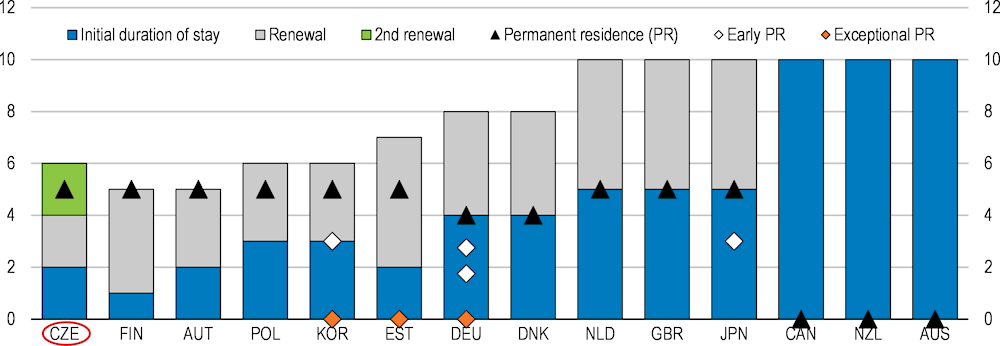

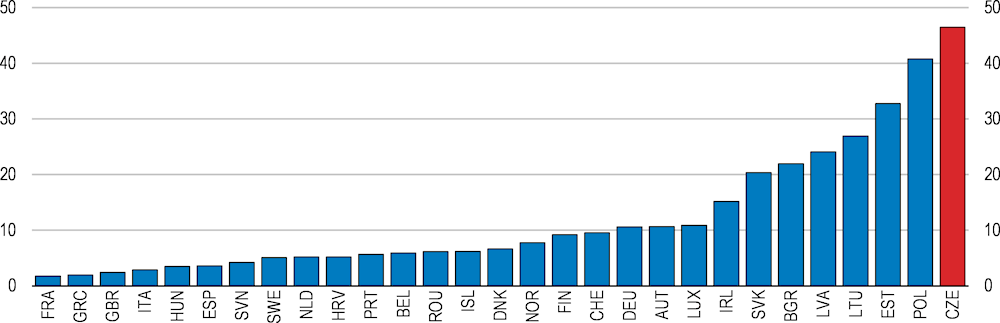

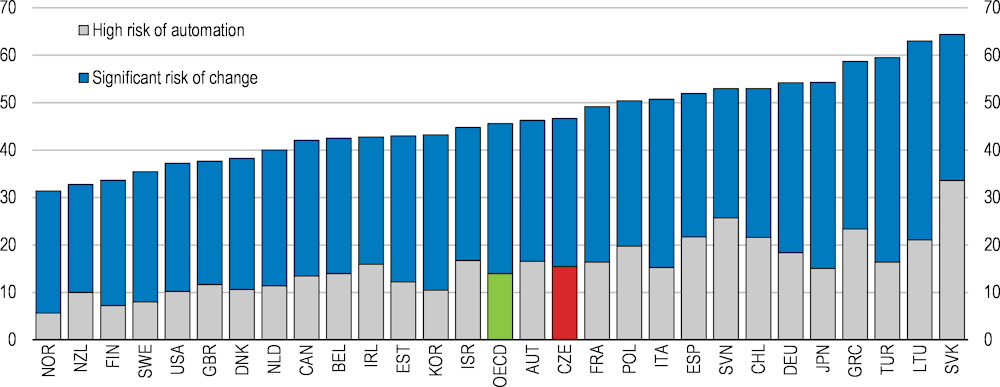

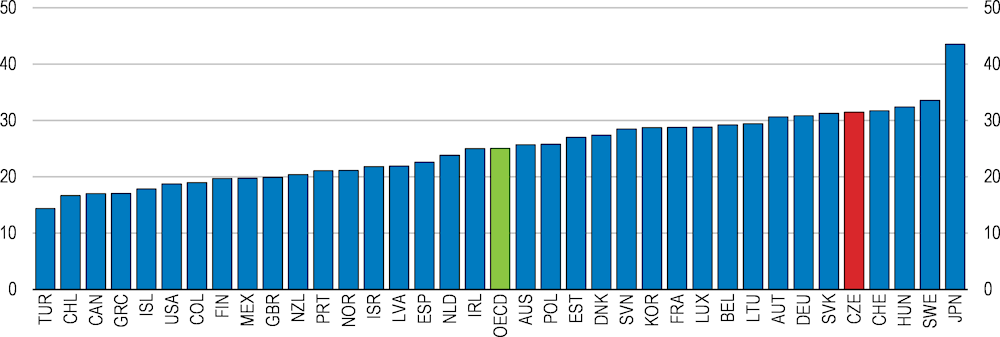

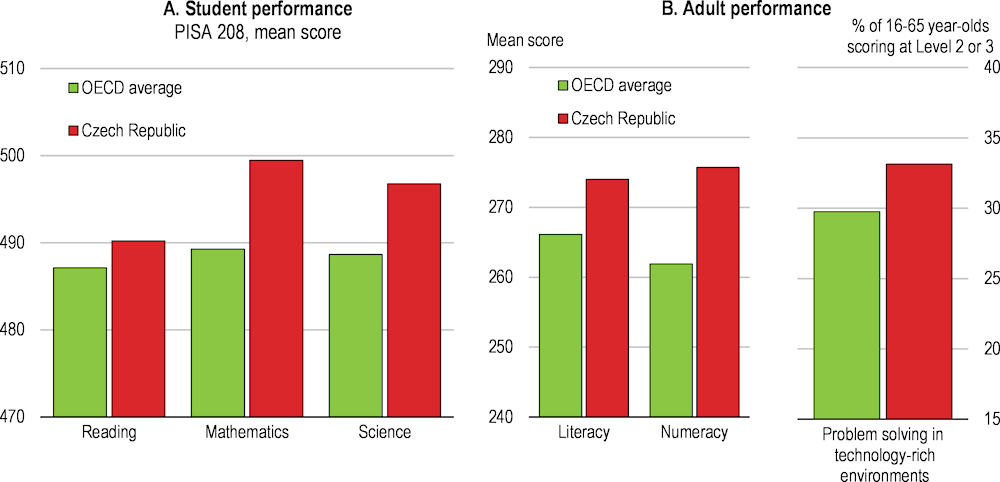

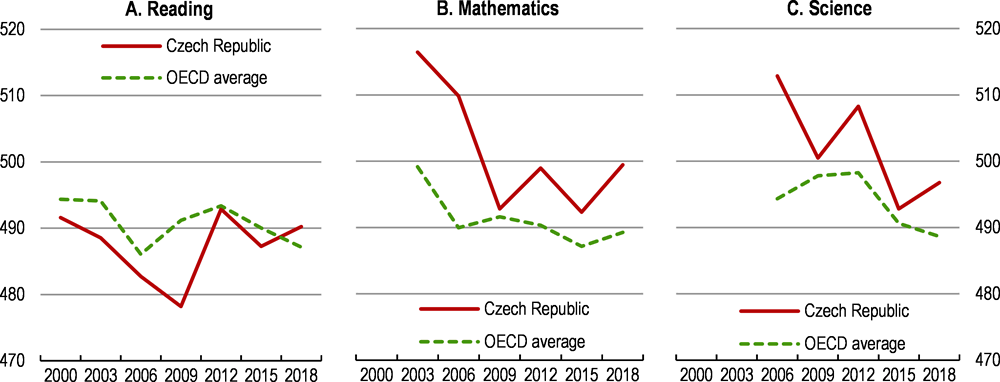

The labour market has performed well, also thanks to the substantial government support during the pandemic, with a very high employment rate and one of the lowest unemployment rates in the OECD. Yet, chronic labour (Figure 1.3) and skills shortages are set to become worse with ageing. Raising labour participation further - notably of underrepresented groups - could aid growth, incomes and equity. Reducing the sizable gender labour income gap and bringing more mothers to work will help in this regard. Increasing labour participation of older workers would limit growing imbalances in the pension system. Raising skills could also boost productivity, which after an impressive period of catch-up still lags behind the OECD average (Figure 1.3). More equitable provision of education and skills and effective lifelong learning would help tackle skills shortages and spur growth. The Czech Republic could also better attract and retain skilled foreign labour.

Figure 1.3. Tackling labour shortages and lifting productivity would increase living standards

1. The job vacancy rate is the number of job vacancies expressed as a percentage of the sum of the number of occupied posts and the number of job vacancies.

2. GDP is measured by GDP at current prices, current PPPs. Labour productivity is measured by GDP per hour worked and labour utilisation is the total number of hours worked divided by the population.

Source: Eurostat; OECD Productivity database.

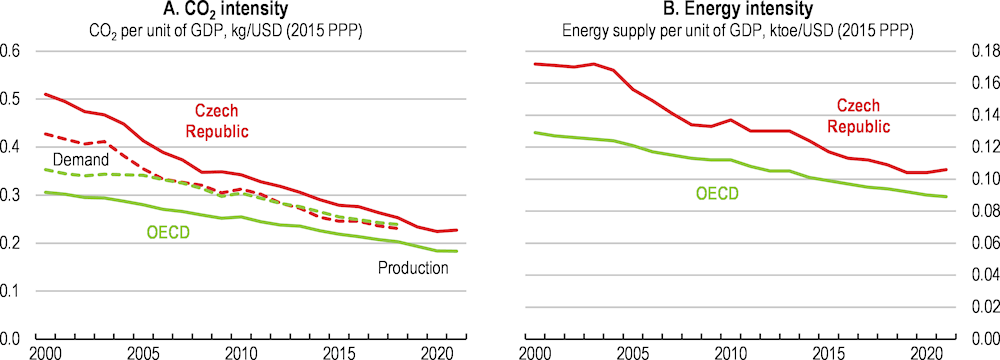

The current energy crisis is an opportunity to strengthen the resolve for climate commitments. The Czech economy is highly energy intensive, still heavily relies on coal and records high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Figure 1.4). In addition, public support for the climate agenda is relatively weak - albeit growing. Steep rises in energy prices - notably gas - present genuine hardship for many households and companies, and the government has introduced measures to cushion their impact. However, incentives to encourage energy-saving behaviour and investments into alternative and renewable sources of energy should be maintained. The availability of considerable recovery funds at the EU level will be an opportunity to step up investments to decarbonise the economy. A stable policy environment, an improved investment climate and a lower regulatory burden can help boost investment and lift growth in a sustainable way.

Figure 1.4. Greenhouse gas emissions and energy intensity are high

Source: Green Growth Indicators, OECD Environment Statistics; IEA World Energy Statistics and Balances.

Against this background, the main messages of this Survey are:

A tight macroeconomic policy is warranted until inflation and inflation expectations are firmly under control. While providing targeted support, steady fiscal consolidation is called for to rebuild buffers and contribute to the fight against inflation. An overdue reform of the pension system would help contain steep future rises in public expenditures due to population ageing.

Higher labour participation would help address chronic labour shortages and support growth. Lengthening the working lives of workers as well as bringing more mothers into employment could raise incomes. Stronger education and skills – notably of disadvantaged children and low-skilled adults – would raise productivity and make growth more equitable. Focusing immigration policy on welcoming high-skilled foreign labour and boosting retention would also raise workforce skills.

Policies to reduce the reliance on coal and greenhouse gas emissions would boost well-being. Once high market prices of energy abate, more ambitious and more equitable pricing of carbon should be pursued. Increased public funding and an improved business climate would boost investment in renewable energy sources and energy efficiency. At the same time, active labour market policies to support workers in job search and reskilling would aid green restructuring.

Box 1.1. Key government policy priorities

Following the general election in October 2021, a new five-party centre-right coalition government was formed. Its current priority is to steer the economy and society in the face of rising costs of living, an energy crisis, slowing economy and the remaining risks stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key priorities of the current government include the following (as listed in its January 2022 Policy Statement):

Stabilisation of public finances: the need for responsible budgetary policy, including in the long term, by reforming and improving public spending without raising the tax burden on the economy.

Focus on the European Union and NATO: emphasis on stable partnerships with democracies around the world and the protection of human rights and democracy.

Pension reform: based on a society-wide consensus that would ensure economic safety in old age for all.

Education: improving education and skills of all, via effective teachers, improved teaching techniques and modern curricula.

Free market support: promoting small and medium-sized enterprises and fostering competition.

Environment: recognising the immediate need to tackle climate change and finding solutions to help protect the environment.

Housing: offering solutions to support owner-occupied and rented housing, including social housing, notably by accelerating building permit proceedings.

Science and research: building on the existing high-quality human capital and innovative potential to further support science and research.

Modern government and digitisation: making public administration modern, lean and flexible by bringing the best talent to provide high-quality services to citizens. Digitising state processes to make state administration more efficient and cheaper, and to deter corruption more effectively.

Responsibility to voters and political culture: improving political culture by relying on honest, competent and trustworthy individuals without conflict of interests; increasing the transparency of the political process.

The economic outlook has deteriorated

The economy has slowed and inflation has risen

The Czech Republic has been strongly affected by Russia’s war against Ukraine through lower global demand, rising energy prices, the risk of energy shortages and generally higher uncertainty. Before the war, virtually all natural gas was imported from Russia, contributing to roughly one third of heat and 8% of electricity production. Russia accounted for more than half of crude oil imports, some of which were delivered through the Druzhba pipeline, which has been exempted from the EU’s oil embargo. Total domestic gas reserves at end-2022 stood at 85% of the total capacity, a high level for the time of year. Through October-December 2022, Czechs consumed roughly 19% less gas compared to the same period over the last three years.

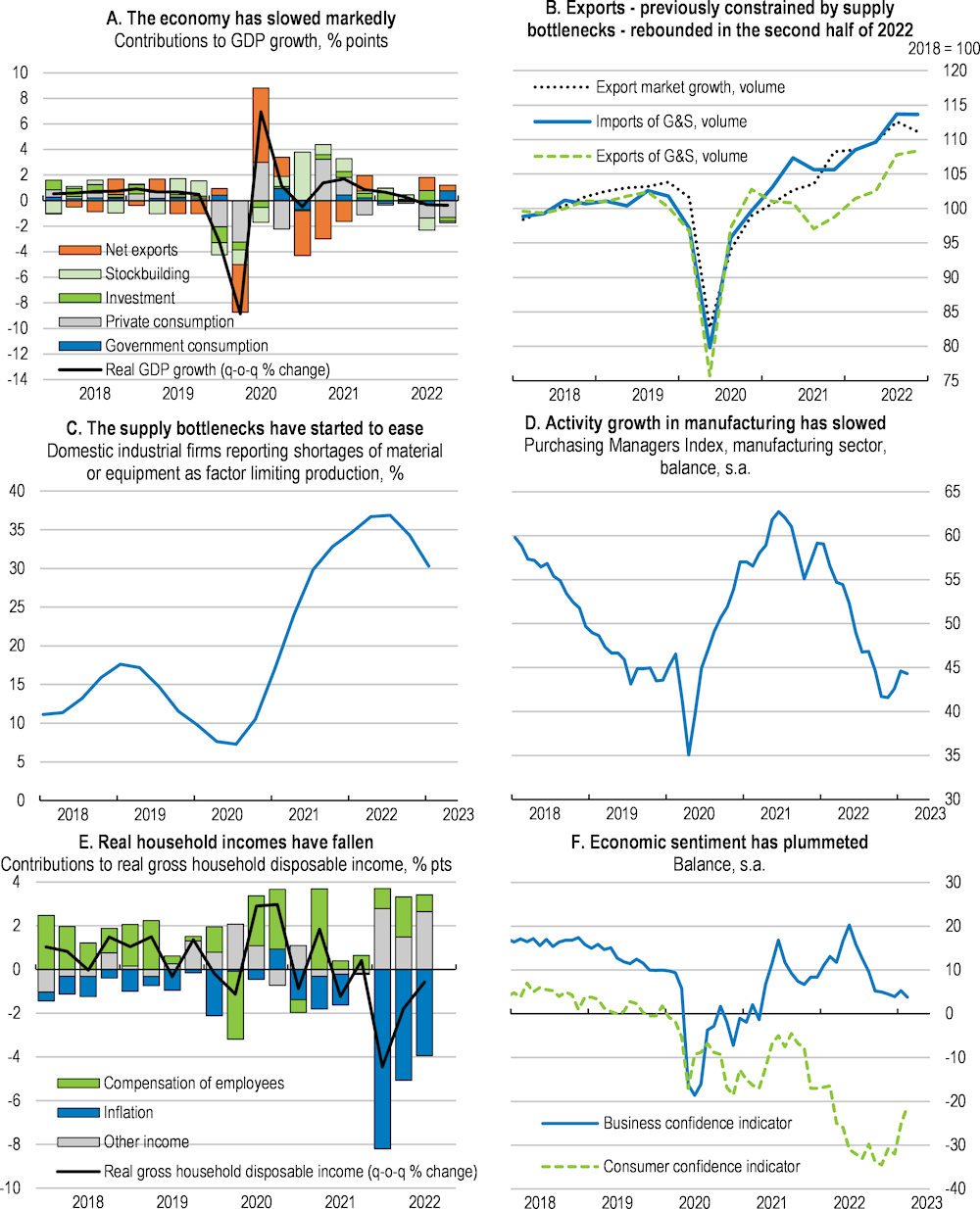

The economy has slowed markedly due to rising costs and weakening domestic demand. Russia’s war against Ukraine has added to pressures on energy and commodity prices. Rising consumer prices have squeezed real household incomes (Figure 1.5). High uncertainty related to the war and the looming energy crisis have contributed to a sharp drop in consumer and business sentiment (Figure 1.5), dampening household consumption and private investment. The services industries, such as accommodation and catering, which had rebounded in early 2022 following the removal of pandemic restrictions, have slowed due to weakened demand and rising input costs. On the other hand, exports – that were for a long time constrained by disruptions in the supply of raw materials and components – rebounded in the second half of 2022 (Figure 1.5), as supply chain bottlenecks started easing.

Figure 1.5. The economy has slowed

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database; Czech National Bank; Refinitiv, Eurostat; Czech Statistical Office.

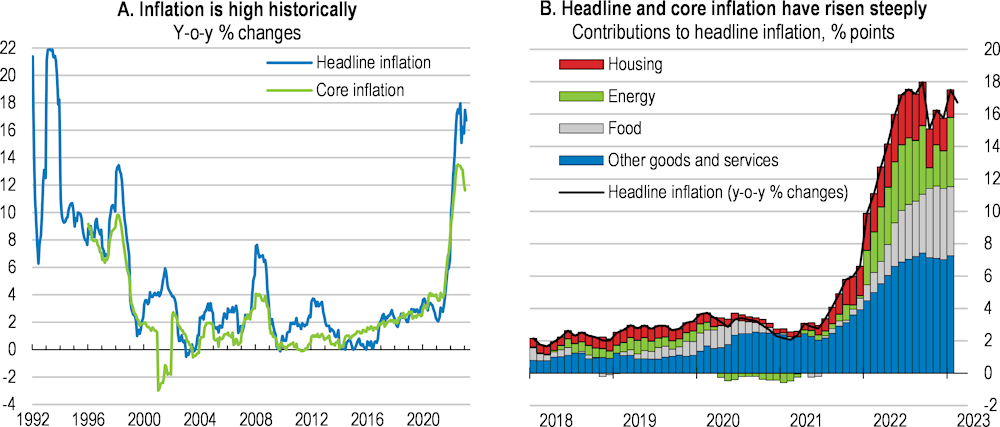

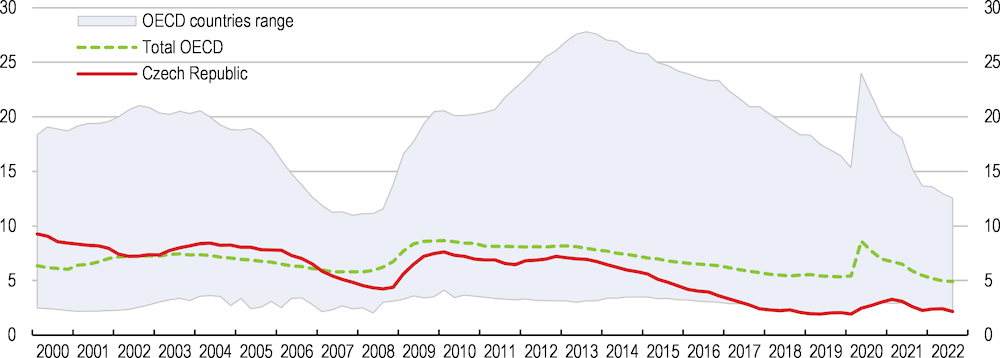

Inflation has risen to very high levels. Consumer price inflation peaked at 18% in September 2022, the highest level in almost 30 years (Figure 1.6). The labour market remains tight (Figure 1.7) and the unemployment rate - at 2.1% in 2022 Q4 – has been the lowest in the OECD. Like prior to the COVID-19 crisis, Czech companies in almost all sectors are once again experiencing labour shortages (Ministry of Finance, 2022a). Yet, nominal wages have risen more slowly than prices, and, in real terms, wages have fallen steeply (Figure 1.7). A large influx of Ukrainian refugees has eased labour market tightness slightly and with high labour demand, they found employment easily. More than a third of refugees of working age were employed as of end-February 2023.

Figure 1.6. Inflation has risen to very high levels

Figure 1.7. The labour market remains tight

Growth will remain moderate, with considerable risks

The economy entered a recession in the second half of 2022, on the back of high energy prices, the threat of energy shortages and continued high uncertainty due to Russia’s war against Ukraine. Annual GDP growth will be subdued in 2023, before picking up in 2024. Private consumption will remain weak due to elevated inflation and diminished household savings that had been accumulated during the coronavirus pandemic. Activity will pick up in 2024 amid eased global supply disruptions. Resuming growth in trading partners will spur exports and trade. In 2023, inflation will start falling from currently very high levels. Real wage growth will turn positive in 2024. Nonetheless, tight financing conditions and slowing public investment due to the transition to the European Union’s new multiannual financial framework will be a drag on GDP growth. The unemployment rate will remain below 3%.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Estimates and projections |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (billion CZK) |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

5,793.9 |

-5.5 |

3.5 |

2.4 |

0.1 |

2.4 |

|

Private consumption |

2,712.0 |

-7.2 |

4.1 |

-0.9 |

-2.7 |

2.4 |

|

Government consumption |

1,134.5 |

4.2 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

3.0 |

1.2 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

1,568.2 |

-6.0 |

0.8 |

6.2 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

5,414.7 |

-4.5 |

2.5 |

1.4 |

-0.3 |

1.7 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

29.8 |

-0.9 |

4.8 |

0.9 |

-0.7 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

5,444.5 |

-5.4 |

7.6 |

2.3 |

-1.0 |

1.6 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

4,284.6 |

-8.1 |

6.8 |

5.7 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

3,935.2 |

-8.2 |

13.2 |

5.7 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

|

Net exports1 |

349.4 |

-0.4 |

-3.6 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

1.7 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Output gap² |

. . |

-1.1 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

-0.9 |

0.2 |

|

Employment³ |

. . |

-1.3 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

. . |

2.5 |

2.8 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

2.8 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

4.3 |

3.3 |

8.4 |

9.1 |

4.2 |

|

Consumer price index |

. . |

3.2 |

3.8 |

15.1 |

13.0 |

4.1 |

|

Core consumer price index4 |

. . |

3.6 |

5.0 |

12.2 |

9.5 |

4.1 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

. . |

14.7 |

14.8 |

8.3 |

7.9 |

7.6 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

2.0 |

-0.8 |

-5.9 |

-4.7 |

-5.1 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

-5.8 |

-5.1 |

-3.8 |

-4.3 |

-3.7 |

|

Underlying government primary financial balance² |

. . |

-2.4 |

-3.5 |

-2.3 |

-1.8 |

-2.4 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

47.0 |

48.5 |

51.0 |

54.0 |

56.5 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht, % of GDP) |

. . |

37.6 |

42.0 |

44.5 |

47.5 |

50.0 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.9 |

1.1 |

6.3 |

7.1 |

5.5 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

1.1 |

1.9 |

4.3 |

5.0 |

3.9 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. Percentage of potential GDP.

3. Following the 2021 Population and Housing Census, new demographic weights were applied in the LFS statistics starting in Q1 2022, leading to a substantial reduction in the number of employed and unemployed persons. Thus, there is a break in the time series and data are not directly comparable. Relative indicators (e.g., unemployment or participation rates) have not been affected by this change.

4. Consumer price index excluding food and energy.

Source: Calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook 112 database.

The outlook is clouded by very high uncertainty. Disruption in supply of energy, notably natural gas in case of depleted storages later in 2023, could restrict economic activity over the next two years. Unexpected further rises in commodity and energy prices, steep high depreciation of the koruna exchange rate and derailed inflation expectations could feed inflationary pressures and make inflation more persistent. A breakdown of trust among social partners could result in a wage-price spiral. Social unrest due to energy shortages and rising energy prices could prompt excessively loose fiscal policy, further fuelling inflation and destabilising public finances. In contrast, deeper recessions domestically and abroad and lower confidence would reduce inflationary pressures. Rising unemployment and higher interest rates could push some debtors in default and dampen demand. A new strain of the coronavirus could dampen growth should restrictive measures be required.

Table 1.2. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Global energy and food crisis |

An intensification of energy and food supply disruptions would further accelerate inflation and cause a contraction in global trade, leading to a deep recession. |

|

Further heightened geopolitical tensions |

Geopolitical instability would increase uncertainty and weaken both domestic and external demand, with negative budgetary repercussions. |

|

Major house price correction and sudden steep rises in interest rates |

A large correction in housing prices could expose vulnerabilities in the financial system, causing a crisis in the financial sector that could feed back to the real economy. In addition, sudden rises in interest rates would sharply increase debt-servicing costs for highly leveraged households and investors, raising the risk of defaults. |

|

Outbreak of a new vaccine-resistant COVID variant |

Further waves of infections could potentially lead to new containment measures and lower domestic and foreign demand (and supply). |

A tight macroeconomic policy stance is warranted

The policy stance fell short of containing inflation

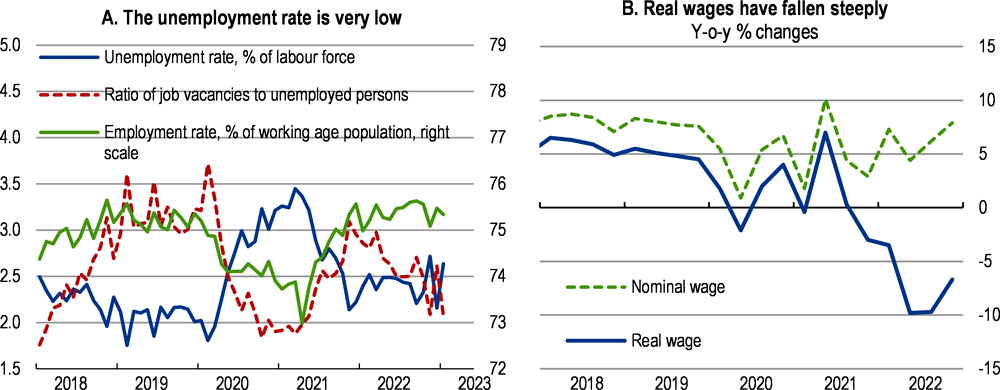

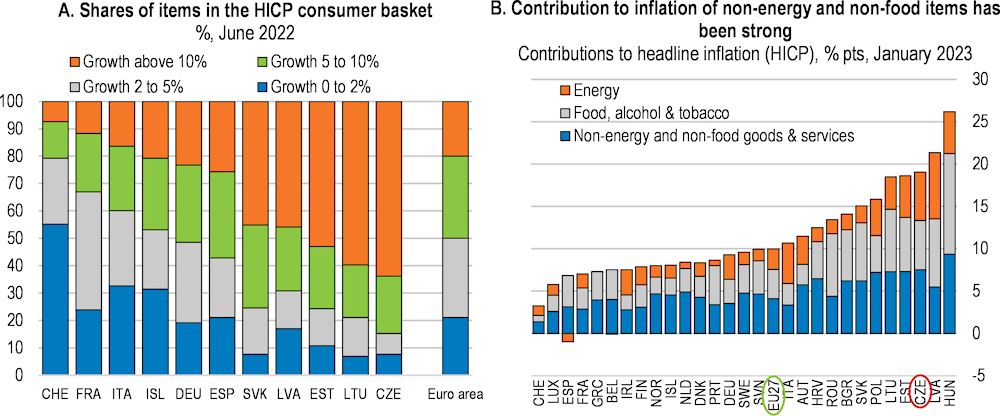

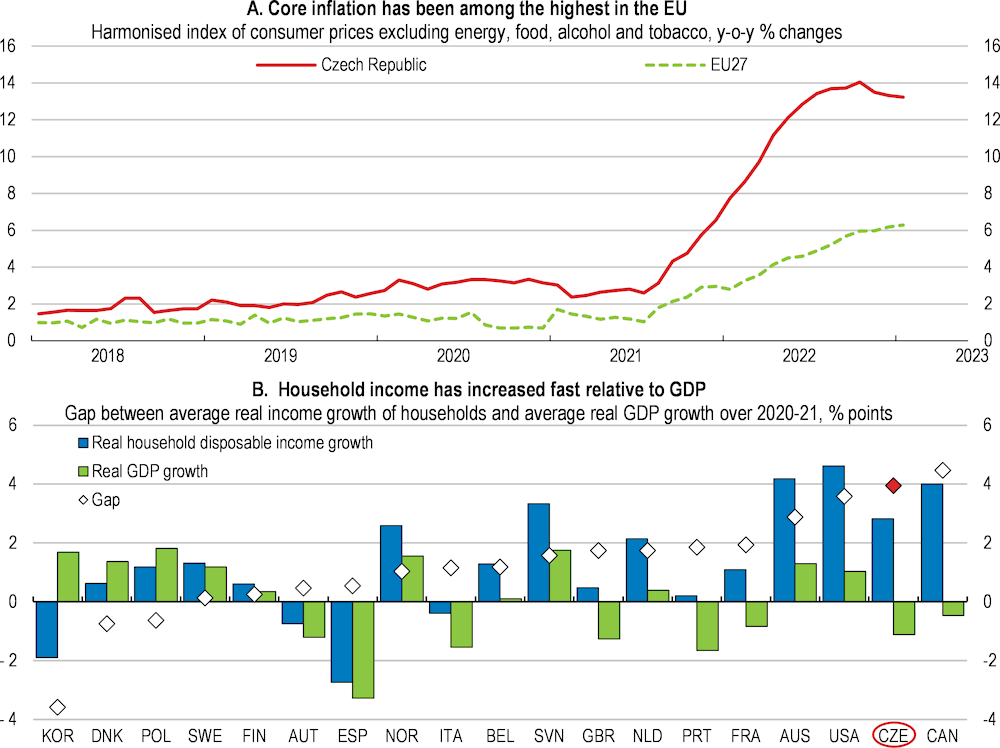

Inflation has risen steeply and become entrenched. Steep rises in volatile prices of energy and food items from abroad only partly account for the take-off of inflation. Price rises have rapidly spread and become broad-based. Core inflation reached 14% in October 2022. The Czech Republic recorded the highest core inflation rates (HICP excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco) among EU economies between December 2021 and October 2022. According to the Czech National Bank (2022a), prices of more than two thirds of the items in the HICP basket rose by more than 10% year-on-year by June 2022, the highest share in the European Union (Figure 1.8). Moreover, the contribution of non-energy and non-food goods and services prices to headline HICP inflation has also been among the strongest in the EU (Figure 1.9).

In hindsight, the combined fiscal and monetary policy stance in 2020-21 was overly accommodative. This boosted demand over supply capacities, resulting in strong inflationary pressures, as manifested in broad-based and steeply rising core inflation and a very tight labour market. Despite an average annual fall in real GDP of 1% over 2020-21, Czech households recorded a 2.8% growth in real incomes (Figure 1.9), boosted by fiscal transfers and tax cuts. This contributed to demand pressures and enabled firms to pass on growing costs to consumers (Czech National Bank, 2022a).

Figure 1.8. Inflation is broad-based

Figure 1.9. Inflation has soared amid growth in household incomes over 2020-21

Monetary policy should remain tight

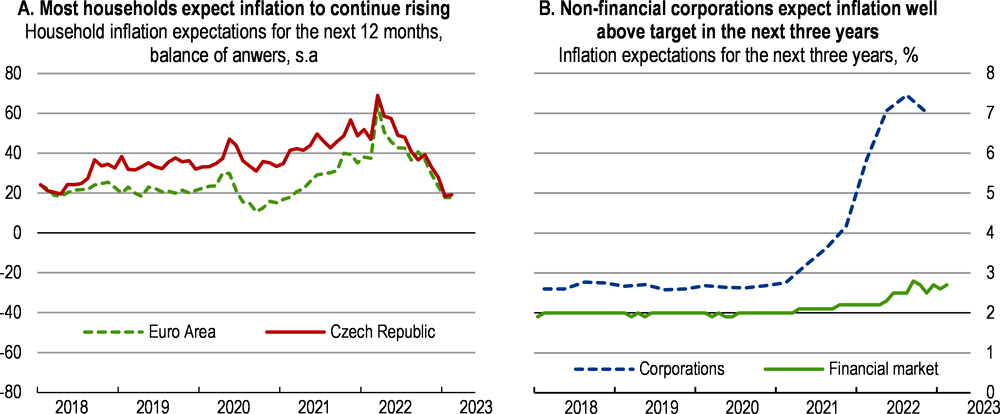

Inflation expectations have increased markedly. Most households expect inflation to continue rising in the next 12 months (Figure 1.10). Surveys show that between June and January 2023, market analysts expected inflation of at least 2.5% at a three-year horizon - above the 2% target level (CNB, 2023, 2022b and 2022f). In contrast, corporations show greater doubts about the ability of the Czech National Bank (CNB) to control inflation, with expectations of inflation at around 7% in three-years’ time (Figure 1.10; CNB, 2022d).

Faced with rising prices and a risk of de-anchored inflation expectations, the CNB has rightly tightened monetary policy. Between June 2021 and June 2022, it raised the policy interest rate from 0.25% to 7%, after which it paused its hiking cycle. In August 2022, the CNB announced that its monetary policy decision was based on a 18-24 month horizon, half a year longer than before, and in November 2022 it based its monetary policy decision on a 15-21 month horizon. Shifting the horizon has been a temporary reaction of the Bank Board to uncertainty connected to the war in Ukraine and its repercussions. Consequently, the inflation target of 2% is now to be reached further away in the future compared with decisions made prior to August 2022.

Figure 1.10. Inflation expectations have increased markedly

Note: Panel A shows balances - differences between the percentages of respondents giving positive and negative replies to a question “In comparison with the past 12 months, how do you expect consumer prices will develop in the next 12 months?”, with possible answers: Increase more rapidly, increase at the same rate, increase at a slower rate, stay about the same, or fall.

Source: European Commission surveys; Czech National Bank.

The CNB has intervened on the foreign exchange market to reduce volatility and to stem depreciation pressures on the koruna. Interventions started in March 2022 and intensified between May and September 2022. In cumulative terms, between May and September, the CNB used 26 billion euros of its international reserves in foreign exchange trading.

The monetary policy stance should remain tight until inflation is firmly on course to decline towards the 2% target. Managing inflation expectations is of paramount importance to prevent costly re-anchoring of expectations. The CNB should continue to weigh carefully the mix of demand and supply pressures on inflation and the high risks surrounding the current outlook. It should reinforce communication about its stated policy goals and tools to achieve them, to give market participants clear and straightforward guidance. While inflation is high and inflation expectations rising, reforms to the central bank’s communication strategy or policy framework can be risky. Moreover, the key policy rate should remain the main monetary policy tool. Foreign exchange interventions should primarily be used to prevent excessive fluctuations of the koruna. Interventions are not a sustainable tool to stave off persistent depreciation pressures, particularly so given the expected narrowing of the interest rate differential with the rest of the world.

The financial sector is resilient but risks stemming from the housing market should be closely monitored

The Czech financial sector is stable and resilient overall. In 2021 and the first half of 2022, it saw solid growth in total assets and profitability. Banks are well capitalised and benefit from ample liquidity. This in part reflects favourable effects of the post-pandemic economic recovery on non-financial corporations and a very low corporate default rate in 2021 and early 2022. Stress tests of the CNB (2022c and 2022e) show that thanks to strong capital buffers the banking sector can absorb shocks and would comply with the regulatory limits on capital and leverage ratios even after a significant shock.

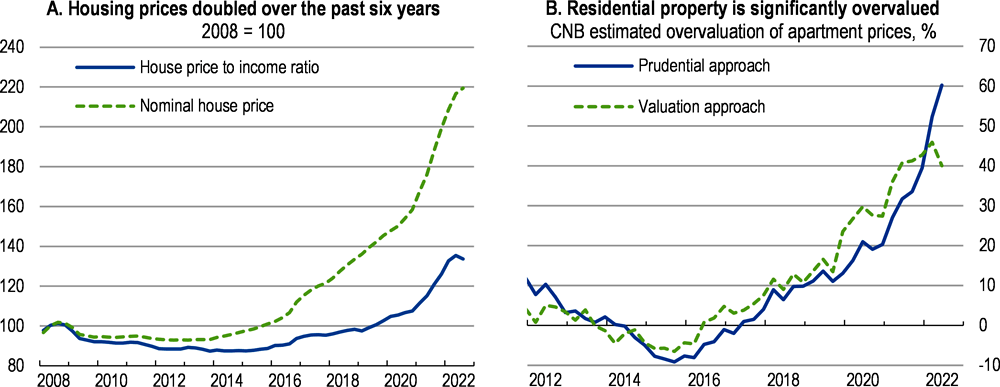

Housing prices continued rising steeply in early 2022 and residential property is increasingly overvalued. Year-on-year growth in residential property prices stood at 25% in Q1 2022. Housing prices doubled over the past six years and grew much faster than incomes (Figure 1.11). The CNB (2022e) estimates that apartments are 40-60% overvalued (Figure 1.11). Worsening affordability has bolstered demand for increasingly outsized loans to allow real estate acquisition. The total amount of new mortgage loans was high in 2021, while credit standards remained relatively relaxed between the second half of 2020 and April 2022. This occurred in part due to looser regulatory requirements on individual mortgage loans. These had been relaxed by the CNB at the start of the coronavirus crisis to support banks’ ability to provide credit. Over this period, the amount of mortgage loans with risky characteristics rose significantly (CNB, 2022c, ESRB, 2022).

Figure 1.11. Housing prices continued rising steeply

Source: OECD, Analytical House Price Indicators database; CNB Financial Stability Report – Autumn 2022.

The domestic banking sector has become increasingly concentrated on property financing loans over the years. Their share in loans to the private non-financial sector reached 63% at the end of 2021. At the same time, the implicit risk weights on housing loans used by banks reached record low levels (CNB, 2022c). Czech households are not highly indebted in international comparison. Yet, a sudden correction of real estate prices or a shock to household incomes would jeopardise their ability to repay and could therefore have a system-wide impact on regulatory capital buffers with potential spillovers to financial stability. With tightening financing conditions, lending to households for house purchase has started to slow significantly. The volume of pure new loans for house purchase fell by roughly 80% year on year in December 2022 (CNB, 2023). The previous high growth in residential property prices, a rising degree of overvaluation and slowing lending activity are creating potential for a significant price correction in the future.

To counter the build-up of systemic risks in the property sector, the CNB reintroduced and tightened limits on new mortgage loans. From April 2022, the basic LTV (loan-to-value) limit is set at 80%, the upper limit on the DTI (debt-to-income) ratio at 8.5 times net annual income and that on the DSTI (debt-service-to-income) ratio at 45% of net monthly income. Higher limits – an LTV of 90%, a DTI of 9.5 and a DSTI of 50% – apply to applicants under the age of 36. In addition, since the amendment to the CNB Act in 2021, the CNB now has legally binding powers to set these limits, as also recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2020a). Before, the CNB could only issue recommendations in this area. However, a general exception applies, where lenders can, in specific cases, approve loans that are not within the prescribed limits, but such loans cannot exceed 5% of the total volume of loans. To monitor and control risks in the property sector beyond what is prescribed under general legally binding provisions, the CNB still uses recommendations.

The CNB has also appropriately raised the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 2.5%, effective from April 2023. This follows the reduction of the countercyclical capital buffer to 0.5% at the onset of the pandemic (from 1.75% applicable at that time) to support bank credit activity. As credit growth resumed, the lower rate was no longer needed. Meanwhile, a deteriorated outlook and higher uncertainty have raised the potential for materialisation of credit risks which calls for higher capital buffers.

Risks stemming from the imbalances in the property market should be closely monitored and macroprudential measures and limits on mortgage loans appropriately adjusted, if needed. When setting the countercyclical buffer rate, the CNB considers the situation on the property market. However, the CNB has acknowledged that the downward trend in risk weights might not appropriately reflect the associated systemic risks (CNB, 2022c). This trend might reverse with the worsened economic outlook and as risks materialise. Also, tighter financing conditions are taking some steam out of the housing market (CNB, 2022e). But risk weights used by banks will rise only slowly. Should imbalances and the risks from the property market continue to grow, the CNB could consider applying the sectoral systemic risk buffer or setting minimum risk weights.

Imbalances also stem partly from a limited and inelastic supply of housing. As discussed in the previous Survey (OECD, 2020a), the process for obtaining construction permits is one of the slowest and most cumbersome in the OECD and among Central and Eastern European countries. Such delays in planning and issuing permits contribute to rising house prices by limiting the supply of residential housing. Furthermore, protracted processes slow down infrastructure investment - including green investment - with repercussions for the wider economy. To speed up and streamline the processes, the government is preparing a comprehensive overhaul of the legislation and regulations related to construction permits. Easier issuance of construction permits, together with reduced red tape, would help drive investment, unleash the entrepreneurial potential and lift productivity growth.

Returning to prudent fiscal policy

Expansionary fiscal policy, notably over 2020 and 2021, has weakened the public finance position. The fiscal balance of the general government went from a small surplus in 2019 to a large deficit of more than 5% of GDP in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 1.12). Public debt rose by 12 percentage points, to 42% of GDP in 2021, and is expected to grow further, to 50% in 2024. Fiscal expansion effectively aided the economy during the coronavirus pandemic by providing a needed fiscal impulse. However, not all measures were well-targeted or linked to the pandemic and, while the pandemic was temporary, some measures permanently worsened the fiscal balance. Most notably, a tax package (lowering personal income taxes and abolishing the real estate stamp duty) adopted in late 2020 permanently reduced tax revenues by close to 2 percentage points of GDP (Czech Fiscal Council, 2021).

Figure 1.12. Expansionary fiscal policy has weakened a strong fiscal position

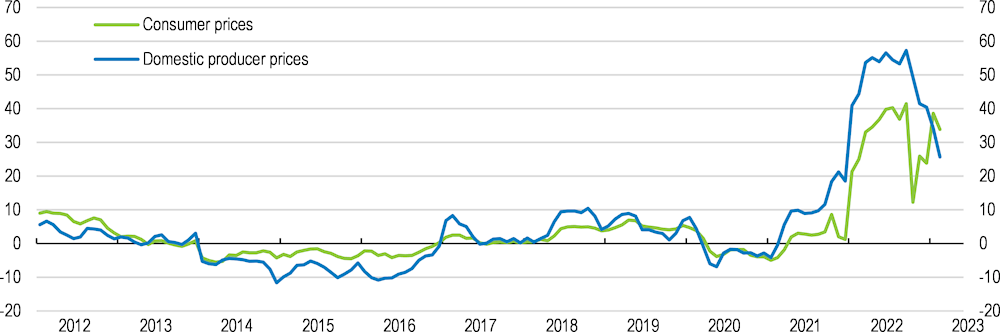

In the current challenging situation, amid the war in Ukraine and rising costs of living, pressures on public spending have risen further. Reflecting NATO targets, the government has committed to raise defence spending more quickly, from the current 1.3% to 2% of GDP by 2024. Czech households are among the most exposed to high gas and electricity prices in Europe due to a high share of energy spending in total consumption (Ari et al., 2022). To counter high prices of energy (Figure 1.13), and high prices of other goods and services the government has introduced several support measures (Table 1.3). Most notably, it has boosted cash benefits and social transfers in kind to help vulnerable households. Additional income support to households and firms highly affected by rising energy prices has been introduced. Several price measures have also been introduced. The government has offered help with energy bills for households, it has eliminated the road tax, temporarily lowered excise tax rates on diesel and petrol and waived the renewable energy levy.

Figure 1.13. Energy prices have risen steeply

Energy prices, year-on-year % change

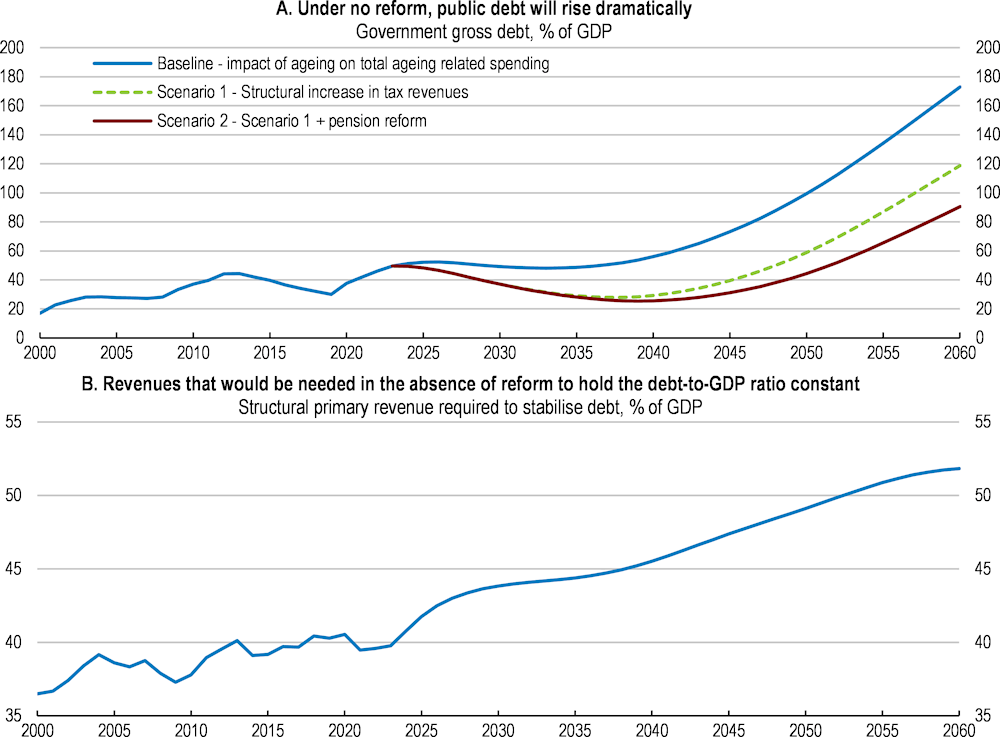

The Czech Republic faces high fiscal pressures in the medium to long term that threaten fiscal sustainability. Both the European Commission and the Czech Fiscal Council have expressed concerns about the fiscal situation (European Commission, 2022a; Czech Fiscal Council 2021 and 2022a). As in many other OECD economies, population ageing will result in steep rises in public spending on pensions, health, and long-term care. Whereas the debt-to-GDP ratio remains relatively benign in international comparison (Figure 1.12), it is set to rise dramatically in the future. Based on long-term OECD scenarios (Guillemette and Turner, 2021), without reform, government debt would rise to 170% of GDP in 2060 (Figure 1.14). In other words, a substantial increase in revenues would be required - - by up to 11 percentage points of GDP in 2060 - to counter the expected rise in expenditures and maintain a constant public debt ratio. Another option would be to cut other spending programmes with potentially adverse effects on equity, productivity, and climate.

With very high inflation and a worsened fiscal situation, fiscal policy should carefully balance the need to cushion living standards with the need to avoid further macroeconomic stimulus. The fiscal policy stance should tighten to support monetary policy in fighting inflation. The role of fiscal policy is to protect the most vulnerable rather than provide blanket support. However, recently introduced measures to counter high prices of energy have been poorly targeted. The tendency to hand out non-targeted cash transfers has continued. For instance, discretionary increases in pensions above statutorily prescribed levels have persisted. Despite already generous cash benefits for families, the government introduced in 2022 a one-off allowance of CZK 5 000 (EUR 200) per child under age 18 for families with children under a certain income threshold, covering 90% of families.

Table 1.3. The government’s policies to offset energy price increases

|

Measure |

Description |

Total amount (billion CZK) |

|

Waiving of VAT on electricity and gas |

Temporary waiving between November and December 2021. |

5.4 |

|

Aid to Households and Entrepreneurs Act |

Targeted assistance for those significantly affected by rising energy prices. Small and medium enterprises that have experienced increases of their energy bills of more than 100% are offered a state-backed guarantee with a 0% interest rate to meet the costs of their operational expenses. |

… |

|

Cash support to households |

One-off allowance CZK 5,000 per child for families with annual gross income up to CZK 1 million (covers about 90% of families). Increase in subsistence and subsistence minimum amounts by 10% from April 2022 and by 8.8% from July 2022. A further increase (by 5.2%) is planned in 2023. The government also increased the housing benefit and changed its parameters. In 2023, the child allowance will be increased by CZK 200. Foster care benefits will also increase. |

13.6 in 2022 and 7.8 in 2023 |

|

Reduced transport taxes and similar |

The government cancelled road taxes for cars, buses and trucks up to twelve tons for 2022. The obligation to add more expensive biofuels to gasoline and diesel was removed. Temporary reduction of duties on petrol and diesel by CZK 1.5 per liter (from June 1 to September 30, 2022). The temporary reduction on diesel was extended until the end of 2023. |

10.9 in 2022 and 13.8 in 2023 |

|

Liquidity lines |

CEZ, the largest utility company operating in the country, signed a credit agreement with the Ministry of Finance in July 2022 for up to EUR 3 billion, providing needed liquidity to the company. |

74 |

|

Energy Savings Tariff and other support |

The government has provided support to all households facing high energy prices from October to December 2022. That is, those who use electricity, gas and households that produce heat through domestic boiler rooms and through central heating. |

21.9 |

|

Waiver of renewable fees |

The government will waive fees for supported renewable energy sources (POZE). This is expected to generate savings of 599 CZK for every megawatt hour of electricity consumed by households and firms. |

4.6 in 2022 and 18.4 in 2023 |

|

Energy price cap |

Energy prices are capped for the year 2023. The cap applies to all households, small and medium-sized enterprises, government institutions, schools, providers of health and social services, operators of urban mass transit, and other entities. Electricity prices are capped at CZK 6.05/kWh, including VAT covering the total consumption for low voltage users (households, SMEs, the self-employed). For small and medium-sized enterprises connected to high and very high voltages, the capping applies to 80% of the highest monthly consumption for that specific month over the past five years (or 80% of the actual consumption in a month if higher than the reference consumption). Gas prices are capped at CZK 3.025/kWh, including VAT, for households and small-volume customers for up to 630 MWh/year. For all small and medium-sized enterprises, it applies only to 80% of their highest monthly consumption over the past five years in that specific month (or 80% of actual consumption if higher). The government has also introduced a price cap on electricity and gas for large enterprises and customers, which are not covered by the measures targeted to SMEs, for the year 2023. |

approx. 83 for households and SMEs and 40 for large energy-intensive enterprises |

|

Temporary electricity and gas support to companies |

Companies with gas supply contracts with an annual consumption of more than 630 MWh will be eligible. Companies that use high or very high voltages and are at an operating loss will also be eligible for support. However, at least fifty percent of the operating loss should be due to the increase in natural gas and electricity costs. Support will be provided from November 2022. |

30 |

The support to counter high energy prices should be better targeted to vulnerable households and price measures should be avoided. Such support can be very costly and tends to predominantly benefit high-income households that are the biggest consumers. In case price measures are introduced, they should be well designed so that they remain strictly temporary and contingent on market price developments. Moreover, price caps should be sufficiently high to preserve incentives for energy-saving behaviour and energy efficiency investments. Any support to firms should also be temporary, targeted to otherwise viable firms, and include incentives to reduce energy use. The Czech Republic should build institutional and statistical capacity to operate a sophisticated transfer and social welfare system that can target vulnerable populations based on several criteria. Besides income, additional criteria could include housing location and quality, household composition and access to public infrastructure (OECD, 2022f).

Figure 1.14. Medium to long term fiscal pressures threaten fiscal sustainability

Note: The projections are illustrative. The OECD Long-term model considers demographics but also the Baumol effect – i.e., the tendency for the relative price of services to increase over time. It is also assumed that other primary expenditures (other than health and pensions) are affected by ageing. The assumption is that governments would seek to provide a constant level of services in real per capita terms. This translates into higher fiscal pressure when the employment / population ratio falls. In addition, the scenarios assume that public pensions will grow roughly at the pace of wages, keeping average benefit ratio constant (Guillemette and Turner, 2021). Panel A shows the required increase in public revenues to keep debt-to-GDP ratio steady amid rising costs due to ageing. Panel B assumes that rising ageing costs are financed with deficits. In scenario 1, we assume an illustrative reversal of the 2020 tax package, resulting in an improvement in structural balance of 2 percentage points of GDP. Scenario 2 adds a pension reform, where statutory retirement age for both genders is raised to 67 by 2037 and rises by half of the expected gain in life expectancy thereafter.

Source: OECD calculations.

Measures on both the expenditure and revenue side should be considered to bring down the deficit. Reversing the recent structural cut in tax revenues, for example by making personal income taxes more progressive, would help close expected future gaps in public budgets. In addition, reducing high social security contributions and shifting towards real estate, consumption and environmental taxes would make the tax mix more supportive of inclusive and sustainable growth. The Ministry of Finance has proposed a temporary windfall tax – in line with EU guidelines – to tax excess profits of firms in energy supply and trading, and fossil fuels as well as large banks. Effective from January 2023 with a duration of three years, it will tax 60% of excess profits that are defined as profits higher than average taxable income over 2018-21, augmented by 20%. Taxing excessive windfall profits of energy producers can be acceptable, as long as it does not discourage investment or put further pressures on prices. However, it undermines tax certainty and might thus worsen the investment climate. Moreover, the commitment and incentives to diversify energy sources and raise investment into renewables should also continue.

Table 1.4. The fiscal position has deteriorated

General government, % of GDP

|

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total revenues |

41.4 |

40.5 |

41.3 |

40.5 |

40.5 |

41.5 |

41.3 |

41.5 |

41.4 |

|

Taxes |

20.1 |

19.5 |

19.8 |

20.3 |

20.4 |

20.4 |

20.3 |

19.9 |

19.2 |

|

Social contributions |

14.6 |

14.5 |

14.3 |

14.7 |

14.9 |

15.4 |

15.5 |

15.9 |

16.6 |

|

Other revenues |

6.6 |

6.6 |

7.2 |

5.5 |

5.2 |

5.6 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

|

Total expenditures |

42.7 |

42.6 |

41.9 |

39.8 |

39.0 |

40.6 |

41.1 |

47.2 |

46.5 |

|

Social protection |

13.8 |

13.4 |

12.9 |

12.7 |

12.3 |

12.4 |

12.5 |

14.3 |

13.6 |

|

Education and health |

12.1 |

12.1 |

11.9 |

11.4 |

11.5 |

12.1 |

12.4 |

14.4 |

14.9 |

|

General public services |

5.2 |

5.2 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

|

Economic affairs |

5.9 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

6.1 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

7.7 |

7.5 |

|

Other1 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

5.8 |

5.1 |

5.2 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

6.1 |

5.8 |

|

Net lending |

-1.3 |

-2.1 |

-0.6 |

0.7 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

-5.8 |

-5.1 |

|

Primary balance |

-0.2 |

-1.0 |

0.3 |

1.5 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

-5.2 |

-4.5 |

|

Gross debt |

56.1 |

55.0 |

51.7 |

47.5 |

43.3 |

40.1 |

37.8 |

47.0 |

48.5 |

|

Gross debt, Maastricht definition |

44.4 |

41.9 |

39.7 |

36.6 |

34.2 |

32.0 |

30.0 |

37.6 |

42.0 |

|

Net debt |

15.6 |

17.8 |

17.8 |

16.7 |

11.5 |

8.7 |

8.0 |

13.6 |

13.1 |

1. Defence; public order and safety; housing and community amenities; recreation, culture and religion; environment protection.

Source: OECD National Accounts database; Economic Outlook database.

On the expenditure side, priority should be given to targeted support to the vulnerable, raising skills, boosting labour participation, as well as productivity-enhancing and green investment. Substantial funding from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (2.9% of GDP, Box 1.2) is an opportunity to pursue a more ambitious consolidation without an overly negative growth impact. Stopping unwarranted cash benefits to pensioners and families could help contain rising public expenditures. There is also room to improve public spending efficiency. Reforms to the pension system and efforts to contain other ageing-related expenditures should be pursued. Based on the long-term OECD model, a structural increase in revenues coupled with later retirement would go a long way to slow the rise in public debt (Figure 1.14).

A more credible fiscal framework is also needed. Current medium-term plans of a structural deficit staying close to 3% until 2025 (Ministry of Finance, 2022c; Czech Fiscal Council, 2022b and 2022d) are not sufficiently ambitious, given the expected future deterioration of public finances. A credible framework to undertake meaningful fiscal consolidation has been lacking since the fiscal rules, described in more detail in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2020a), were loosened in 2020. While the debt brake rule is still in place (with a debt-to-GDP limit of 55%, after deducting cash reserves), the structural deficit rule has been loosened and there is no firm requirement for the pace of fiscal consolidation (Czech Fiscal Council, 2022a; 2022c; Ministry of Finance, 2022c). The Czech economy would benefit from re-establishing the requirement of a 0.5 percentage point improvement per annum in the structural balance up to a predetermined objective (1% of GDP structural deficit as prior to the amendments to fiscal rules).

Box 1.2. EU funds to support a resilient recovery and the green and digital transition

The EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) was set up to support economic recovery after the pandemic and facilitate the green and digital transformation.

The Czech Republic is set to receive EUR 7 billion (2.9% of 2021 GDP) in grants, to be disbursed by 2026. In addition to supporting the climate and digital transitions as described below, several programmes are geared to reinforce economic and social resilience. The plan allocates EUR 222 million to improve the business environment. Reforms and investment of EUR 393 million will help foster equal access to education, notably through increasing access to affordable pre-school care, reinforced support for disadvantaged schools and additional tutoring for children at risk of failure. Investments of EUR 823 million will increase the resilience of healthcare services.

Climate objectives

42% of the RRF grants will support Czech climate objectives. Of this, EUR 1.4 billion will finance large-scale renovation programmes to increase the energy efficiency of residential and public buildings, including childcare and social care facilities. The RRF also supports the decarbonisation of transport through EUR 1.1 billion of investments in railway infrastructure and to promote electric charging stations and cycling pathways. Furthermore, EUR 480 million will be invested in installation of renewable energy sources for both businesses and households. EUR 141 million will be invested in the circular economy, including recycling infrastructure and support for circular economy solutions and water savings in businesses. Reforms in forestry management aim at increasing the sustainability of Czech forests.

The EU launched its REPowerEU Plan after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to scale up renewable energy sources, boost energy efficiency measures and reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels. The plan adds additional grants of EUR 20 billion (beyond the initial RRF allocation) to accelerate the implementation of the climate and energy saving plans of member states. The allocation of grants will take into account member states’ dependence on fossil fuels. However, the final allocation remains to be decided.

Digital transition

The Czech Republic will use 22% of the RRF grants for investments and reforms in skills, e-government, digital connectivity and digital transformation of businesses. EUR 585 million will be for digital equipment of schools, training for teachers, new higher education programmes in digital fields and upskilling and reskilling courses. In addition, EUR 585 million will support the digital transformation and cyber-security of public administration, the justice system and health care. EUR 650 million will be invested in the digital transformation of businesses, European digital innovation hubs, testing and experimentation facilities for Artificial Intelligence in manufacturing, very high-capacity networks and 5G networks.

Source: European Commission.

Box 1.3. Potential impact of reforms

Structural reforms can boost economic growth and incomes. Table 1.5 quantifies the impact on growth of some of the reforms recommended in this Survey (quantification is not feasible for all of them) based on the OECD long-term model and OECD estimates of relationships between reforms and total factor productivity, capital deepening and the employment (Égert, 2017). The analysis suggests that if the Czech Republic implemented the selected set of reforms (see below), per capita income could increase by about 6% in 10 years and up to 17% in 25 years. The estimates are illustrative.

Table 1.5. Potential impact of structural reforms on per capita GDP

|

10 years |

25 years (up to 2050) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Strengthen tax revenues, including through more progressive personal income taxation, shift towards real estate, consumption and environmental taxes, and reduce social security contributions. |

0.6% |

0.7% |

|

Reduce inequities in schools and modernise VET education. |

1.3% |

7.2% |

|

Improve investment climate and business environment (lower administrative burden, modernise construction permits). |

2.7% |

6.1% |

|

Boost active labour market policies. |

0.6% |

0.7% |

|

Keep expanding the supply of affordable and high-quality childcare facilities. |

0.4% |

0.6% |

|

Pension reform (increasing the age of retirement). |

0.4% |

2.0% |

|

Package of reforms |

6.0% |

17.3% |

Note: Simulations are based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model with a no policy change scenario used as the baseline. The following changes in policy/outcomes are assumed. The tax reform assumes a reduction in the average tax wedge by 2 percentage points of labour costs (the 2020 reform implied a 4-percentage point reduction, but here a partial reversal is assumed). Reform in education is assumed to be equivalent to an increase in average years of schooling by 0.7 years over 15 years (to close half of the gap with the current level in Germany). Improvement in the business environment assumes the PMR components "Simplification and Evaluation of Regulations" and "Administrative Burden on Start-ups" reach the average of the top five OECD performers over five years. Active labour market policies are boosted to reach the average of five top performers in the OECD (as % of GDP per capita per unemployed person). Expanding childcare is modelled as family benefits in kind (% of GDP) increased to OECD average. Pension reform: retirement age goes up to 67 for both men and women by 2037, and then by half of the expected gain in life expectancy thereafter.

Source: OECD calculations.

The estimates in Table 1.6 quantify the direct fiscal impact of selected recommendations included in the Survey, and do not seek to incorporate any dynamic effects. The estimates are illustrative.

Table 1.6. Illustrative direct fiscal impact of selected recommended reforms

|

Reform |

Fiscal impact (savings (+)/ costs (-)) (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

|

Strengthen tax revenues, including through more progressive personal income taxation, shift towards real estate, consumption and environmental taxes, and reduce social security contributions. |

+2% |

|

Reduce inequities in schools and modernise VET education. |

-0.7% |

|

Improve investment climate and business environment (lower administrative burden, modernise construction permits). |

Negligible |

|

Boost active labour market policies. |

-0.2% |

|

Keep expanding the supply of affordable and high-quality childcare facilities. |

-0.4% |

|

Pension reform (increasing the age of retirement). |

+1.3% (by 2050) |

|

Investing in the green transition |

-1.3% to - 2.0% |

|

Total net effect of listed reforms |

+0.0% - +0.7% |

Note: The fiscal cost of the education reform is based on the estimated long-term increase in the cost of education from the 2022 Convergence programme of the Czech Republic. The fiscal cost of the green transition represents the low- to mid-point estimates in Ščasný et al. (2022) of the cost of investment up to 2030. The fiscal cost has been adjusted for the EU funds from the RRF and REPowerEU, as well as the anticipated increase in GDP. The fiscal dividend of the pension reform is computed by taking a difference between the required increase in government revenues to keep debt-to-GDP ratio stable in “baseline” and “pension reform” scenarios. Based on simulations of the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Source: OECD calculations.

Safeguarding long-term fiscal sustainability

Strengthening public revenues

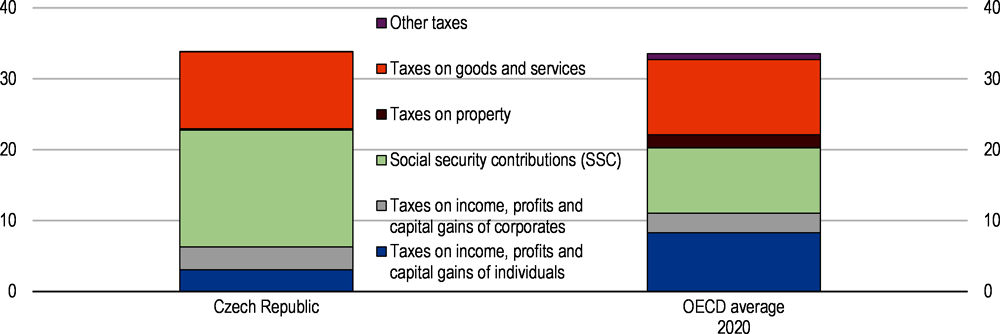

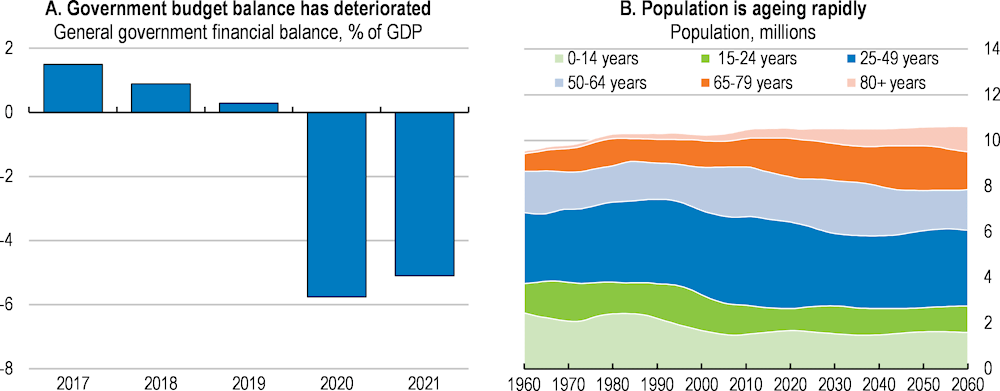

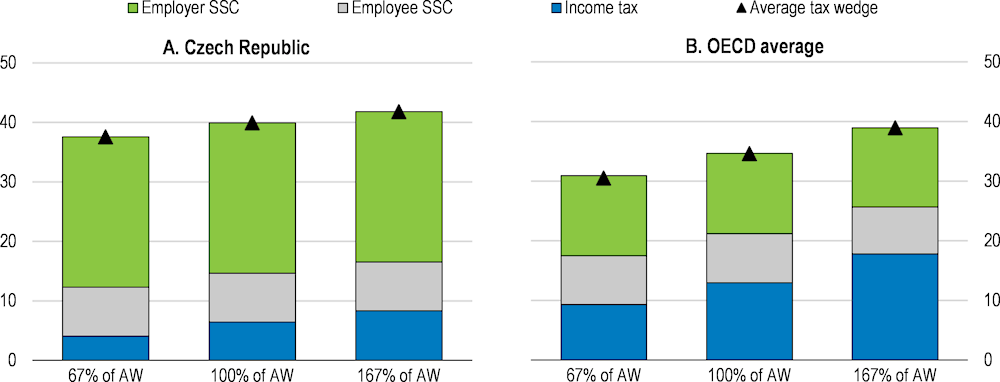

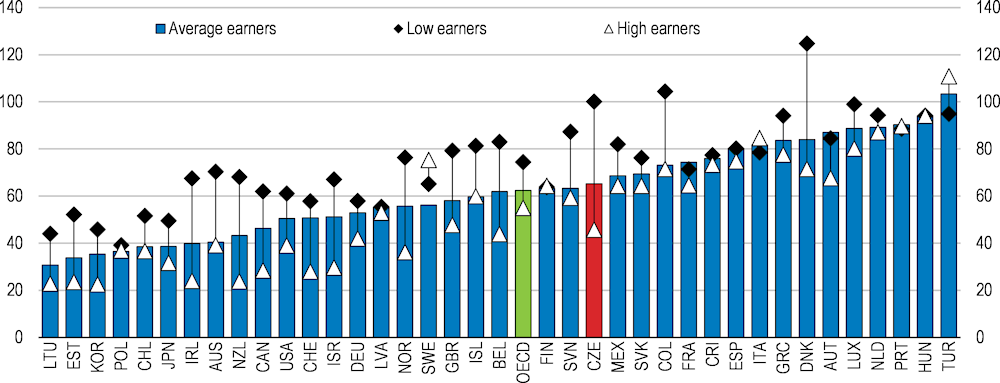

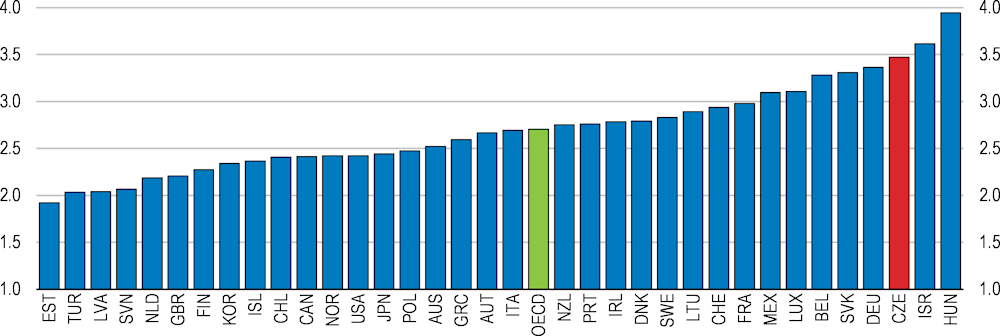

Efforts to bolster tax revenue should also aim to improve the tax mix. Tax revenue collection as a share of GDP is close to the OECD average. However, the Czech Republic relies significantly more on social security contributions (Figure 1.15) and less on personal income taxes (PIT) and property taxes than other OECD countries. The average tax wedge – the gap between the take-home pay of workers and their costs to employers – is high in international comparison due to elevated social security contributions (Figure 1.16). Evidence shows that high average tax wedges can raise costs for companies and slow growth (Arnold et al., 2011, Akgun et al., 2017). Lower reliance on social security contributions and higher revenues from property taxes and indirect taxes, including environmental taxes, could boost growth durably and reduce the exposure of government revenue to ageing. A lower tax wedge could also help ease labour market tightness by giving room to attract workers at the margins of the labour market.

Figure 1.15. Tax revenues rely heavily on social security contributions

General government tax revenues, % of GDP, 2021

Figure 1.16. The tax wedge is high

Average tax wedge decomposition, % labour costs, 2021

Note: Single individual without children at different income levels of the average worker (AW).

Source: OECD Taxing Wages database.

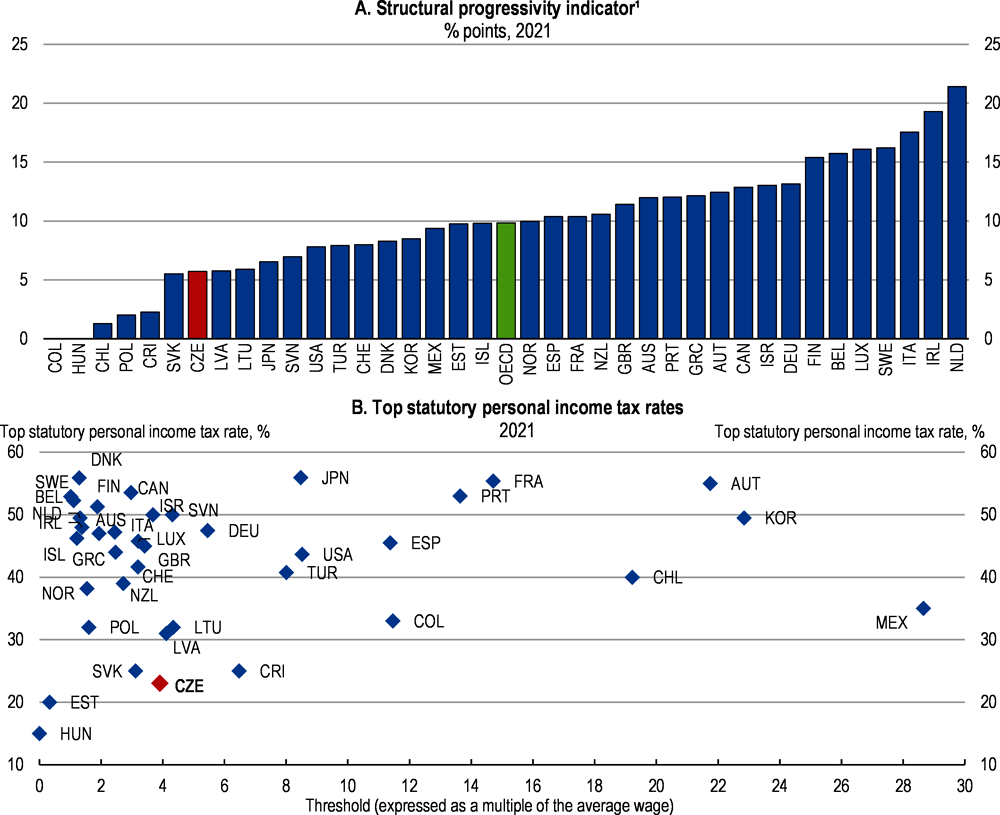

The 2020 PIT tax reform - effective since January 2021 - has permanently reduced tax revenues. The concept of “supergross wage” (which included the social security contributions of employers) as a tax base for PIT from employment income was abandoned. Instead, the tax base is now determined based on gross income, with employment income taxed on gross wage. A previously flat PIT tax rate at 15% (and solidarity surcharge of 7% for very high incomes) was replaced with a progressive tax schedule, with marginal rates of 15% and 23%, with the second bracket starting at a gross income of four times the average wage (OECD, 2022). In addition, the general tax credit was raised in total by 24% and tax credits for the second child or more were raised by 15% (OECD, 2022a). As a result, for high-income persons, employment income is effectively taxed at the same rate as before the reform, while some types of non-employment income – capital gains and rental income – will now be taxed at a higher marginal rate of 23%. For most taxpayers, the tax burden has been reduced. Yet, the progressivity of the PIT remains low (Figure 1.17). The recent unfunded cut in the PIT should be reversed to raise revenues for expected rises in public spending. Higher collection of the PIT could be partly achieved by higher progressivity with a higher number of tax brackets and higher top marginal tax rates for high earners.

Figure 1.17. Progressivity of the personal income tax remains low

1. The structural progressivity indicator measures the percentage point change of the average income tax rate for a single person with no children if their income increases from 67% to 167% of the average wage.

Source: OECD Taxing Wages database; OECD Tax database.

There is room to further improve VAT collection, notably by improving compliance and reversing exemptions and reductions granted in recent years. There has been good progress in tackling tax evasion but the VAT compliance gap at 11.9% remains above the EU average of 9.1% (Figure 1.18; European Commission, 2022c). The project of introducing the electronic registration of sales, whose roll-out was put on hold during the coronavirus pandemic, is to be fully abolished in 2023 due to reportedly poor results and a high administrative burden (Ministry of Finance, 2022b). However, efforts to improve compliance and fight tax evasion and fraud need to continue, including by taking on opportunities offered by digitalisation. According to the VAT Revenue Ratio indicator (OECD, 2020c and 2022g), in 2020, the Czech Republic lost a lower proportion (41%) of its potential VAT revenues than OECD countries on average (44%) due to VAT exemptions, reduced rates, weak enforcement or VAT non-compliance. However, the share has seen a slight increase over the last three years, due to an increasing number of items on reduced VAT rates. Reclassification to lower VAT rates of selected goods and services in 2020 (during the pandemic), including accommodation, sports and cultural events and ski lifts, should be reversed. Overall, the use of reduced VAT rates should be further diminished. International evidence shows that reduced VAT rates are poorly targeted as they benefit richer households proportionally more and are not effective in giving support (OECD, 2019a and 2020d).

Figure 1.18. The VAT tax compliance gap remains above the EU average

VAT gap, % of VAT Total Tax Liability (VTTL), 2020

Note: The VAT GAP is the overall difference between the expected VAT revenue and the amount actually collected.

Source: European Commission, Directorate-General for Taxation and Customs Union, Poniatowski, G., Bonch-Osmolovskiy, M., Śmietanka, A., et al., VAT gap in the EU : report 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, 2022, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2778/109823.

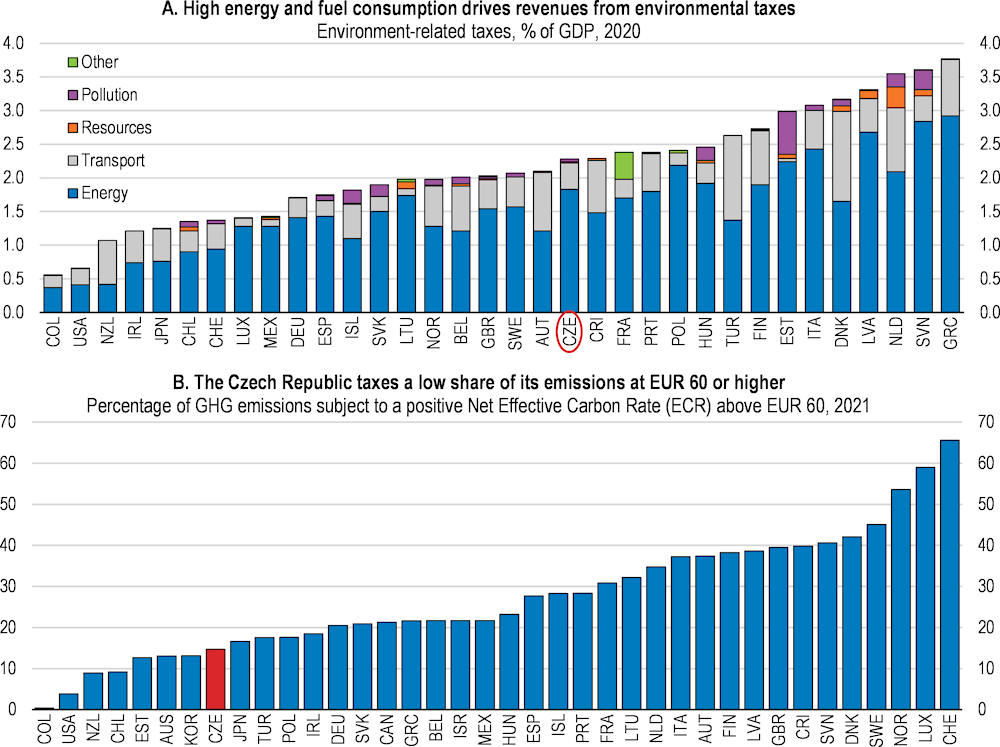

High energy and fuel consumption drives revenues from environmental taxes, but relatively low rates do not effectively discourage polluting behaviour. There is no explicit carbon tax. The OECD (2021b and 2022h) estimates that in effective terms (taking into account emission trading schemes, fuel and other excise duties and carbon tax) the Czech Republic taxes only about 15% of its emissions from energy use at EUR 60 or higher per tonne of CO2. This is among the lowest shares in the OECD (Figure 1.19). As discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, a revised tax structure could better align economic and environmental objectives to help reach climate goals and alleviate air pollution. Implicit carbon prices are sufficient in the road sector (apart from temporary reductions in 2022 and 2023), but levies on diesel are lower than on gasoline, despite the former’s higher carbon content. Taxes on natural gas, coal and other solid fuels and electricity are low and are not adjusted for inflation. Exemptions are applied to various fuel uses that decrease end-use prices and reduce incentives to save energy or switch to cleaner fuels. For instance, exemptions apply for residential heating and in agriculture (OECD, 2018a). The Czech Republic should prepare a plan to phase out these exemptions once the current uncertainty abates.

Figure 1.19. Effective taxation of carbon is low

Source: OECD Environmentally related tax revenue dataset; OECD (2022), Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Turning Climate Targets into Climate Action, OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation, OECD Publishing, Paris.

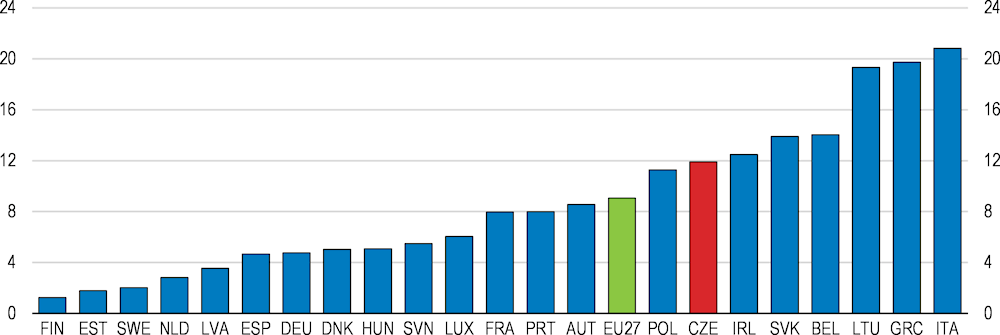

Total revenue from property taxes in terms of GDP is one of the lowest in the OECD (Figure 1.20). Revenues have been reduced further by the abolition of the real estate acquisition tax from January 2021. As discussed in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2020a), Czech municipalities could benefit from raising more revenue from the property tax. This tax is among the least distortive for growth, can better withstand population ageing and provides relatively stable revenues, which benefits local governments with largely non-cyclical spending (Arnold et al., 2011; Kim and Vammalle, 2012; Blöchliger, 2015; Colin and Brys, 2019). In the Czech Republic, the property tax comprises a land tax and a tax on buildings, and the calculation of the tax is based on the size of property rather than its value. The base rate is set at the central level, but municipalities can raise the rate up to five times the minimum threshold amount. Yet, most municipalities tend to set their local property tax rate at the low level, and many set exemptions, further reducing the tax base (Radvan, 2019). The tax evaluation should be based on regularly updated estimates of property value, as in Denmark, Estonia, Spain and the United Kingdom, among others, rather than size.

Figure 1.20. Property tax revenues are low

Recurrent taxes on immovable property, % of GDP, 2021 or latest available year

The self-employed continue to benefit from favourable tax treatment, raising concerns about sustainability and fairness. The tax code allows them to deduct between 30% and 80% (depending on occupation) of revenue as cost to derive net income, eliminating the need for cost accounting. A turnover threshold under which a flat rate deduction (instead of expenditures) can be used to narrow the tax base is quite generous, reducing revenues from personal income taxes. Furthermore, the assessment base for social security contributions is set at 50% of net income (with a minimum of 25% of the average wage), effectively lowering the overall contributions of self-employed workers compared to employees. The self-employed enjoy the same rights from the health care system as employees, but they contribute significantly less. They also contribute less towards pensions, resulting in lower benefits, but high solidarity within the pension system redistributes strongly in their favour. According to OECD estimates (2020b), a self-employed worker with net income equivalent to that of an average-wage worker can expect to receive 83% of the pension of the average-wage worker but pays only 67% of the contributions. As recommended by the OECD Pensions Review (OECD, 2020b), the contribution base for the self-employed should be closer to that of employees, for instance at around 75% of net income.

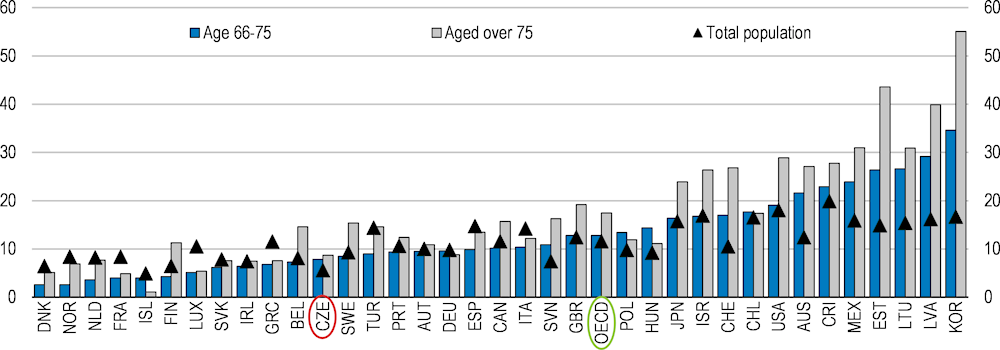

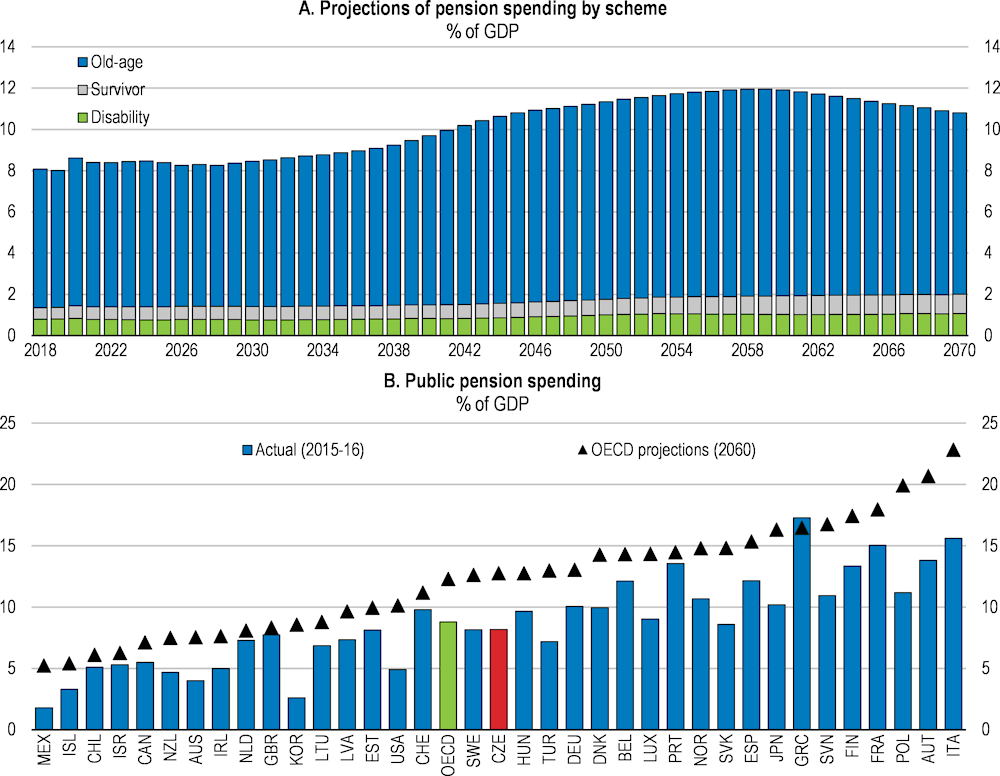

Addressing rising public costs of pensions

Due to rapid population ageing, without further reforms, pensions will exert high pressures on public spending from 2030 (Figure 1.21). The ratio of elderly people (65 and over) to the working-age population (20-64) is projected to rise from 34% to 56% between 2020 and 2050 (OECD, 2021a). Considering the increase in the statutory retirement age to 65 in the coming years, the economic dependency ratio (ratio of the population at and over the retirement age to the working-age population) will remain stable until 2035, before rising steeply until about 2060 (Figure 1.22). According to the simulations made with a cohort model (OECD, 2020b), pension spending will remain stable at around 8.5% of GDP until 2030. It will then increase progressively to peak at 11.9% of GDP in 2059 and then decline along with the size of the elderly population (Figure 1.21).

Figure 1.21. Pensions will exert high pressures on public spending from 2030

Note for panel B: 2050 for Australia, Canada, Iceland Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Switzerland, Republic of Türkiye and the United States. OECD projections refer to Guillemette, Y. (2019), “Recent improvements to the public finance block of the OECD’s long-term global model”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1581, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4f07fb8d-en.

Source: OECD (2020b), OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Czech Republic, OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6387738-en

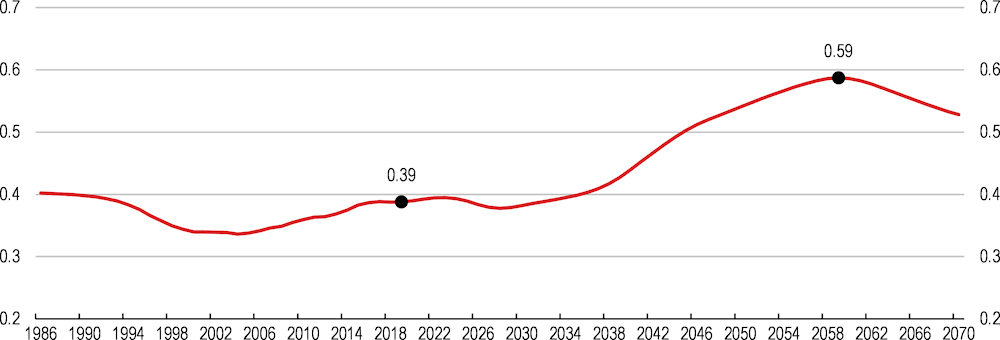

Figure 1.22. The economic old-age dependency ratio will rise

Ratio of elderly (statutory retirement age (SRA) and over) to working-age adults (19-SRA)

Note: The economic old-age dependency ratio is the ratio of the population at and over the statuary retirement age (SRA) to the working-age population.

Source: OECD (2020b), OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Czech Republic, OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6387738-en

The Czech pension system is strongly redistributive. The old-age pension consists of a flat-rate component (basic pension) and an earnings-based component with strong caps on pensions of higher-earners, weakening the link between pension contributions and future benefits. The resulting benefit structure is highly compressed. Rates of poverty in old age are low (Figure 1.23). The net replacement rates are close to the OECD average (Figure 1.24) but are relatively high for low earners and low for high earners. To the latter, the system offers a very low internal rate of return to paid contributions (OECD, 2020b). In the Czech old-age pensions system, high earners (twice the average wage) have replacement rates well below average-wage earners (46% versus 65%), a large gap by international comparison (55% versus 62% for the OECD on average).

Figure 1.23. The old-age poverty rate is relatively low

Relative poverty rates (50% of median income), 2019 or latest available year

Figure 1.24. Net replacement rates are close to the OECD average, but low for higher earners

Net pension replacement rates, %

Note: The values of all pension system parameters reflect the situation in 2020 and onwards. The calculations show the pension benefits of a worker who enters the system that year at age 22 – that worker is thus born in 1998 – and retires after a full career.

Source: OECD (2021a), Pensions at a Glance 2021.

To increase replacement rates for high earners, the recent OECD Pension Review (OECD, 2020b) proposes to finance some of the redistributive part of the system (e.g., basic pensions) through general taxes, which could allow for higher accrual rates, in particular for higher earners. In the Czech Republic, redistribution takes place exclusively within the pension system as all pension revenues come from contributions levied on wages (except for transfers from the budget to cover any deficit in the system). In contrast, many countries finance part of pension spending through taxes. Financing parts of the system through taxes would help to strengthen the link between paid contributions and benefits. Furthermore, it could help to ease some of the burden of very high mandatory social security contributions.

Pensions are indexed to a combination of the consumer price index (or pensioners’ cost of living index, whichever is higher) and half of the real wage growth. The indexation is carried out once a year on 1st January. But if inflation reaches at least 5% since the end of the previous reference period, an extraordinary round of indexation during the year is triggered. However, pensions have been frequently increased beyond the statutory prescribed levels. For instance, it has been decided to give an additional CZK 1000 (around EUR 40) per month to all pensioners of age 85 and over, starting in 2019 (Ministry of Finance, 2019). In 2019, the flat-rate component of pension benefits was increased from 9% to 10% of the average wage, resulting in an overall increase of the average monthly pension by CZK 900 (EUR 37) in 2020. In addition, as a solidarity measure during the pandemic, all pensioners were given a one-time lump sum of CZK 5 000 (around EUR 200) at the end of 2020. The overall cost of the listed discretionary measures amounted to roughly 0.5% of GDP in 2020 (Ministry of Finance, 2020 and 2021), half of it with a permanent effect. Furthermore, while statutory indexation of pensions implied high increases due to high inflation, pensioners were given CZK 300 (EUR 12) per month from January 2022 on top of statutory indexation. From January 2023, pensioners - primarily women - will start receiving a benefit (CZK 500 per month) for each child raised, which will amount to an additional cost of roughly 0.3% of GDP.

Discretionary measures to increase pensions beyond the statutory indexation add to steep spending increases and hamper pension sustainability. To maintain pension adequacy, the focus should rather shift to prolonging working lives by increasing the statutory retirement age.

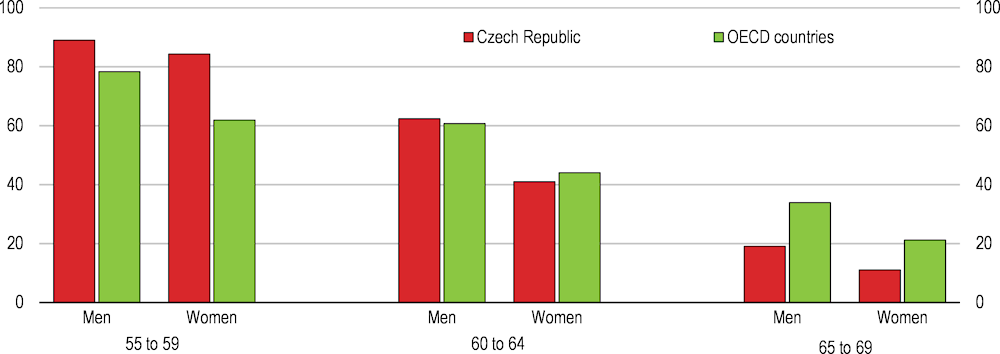

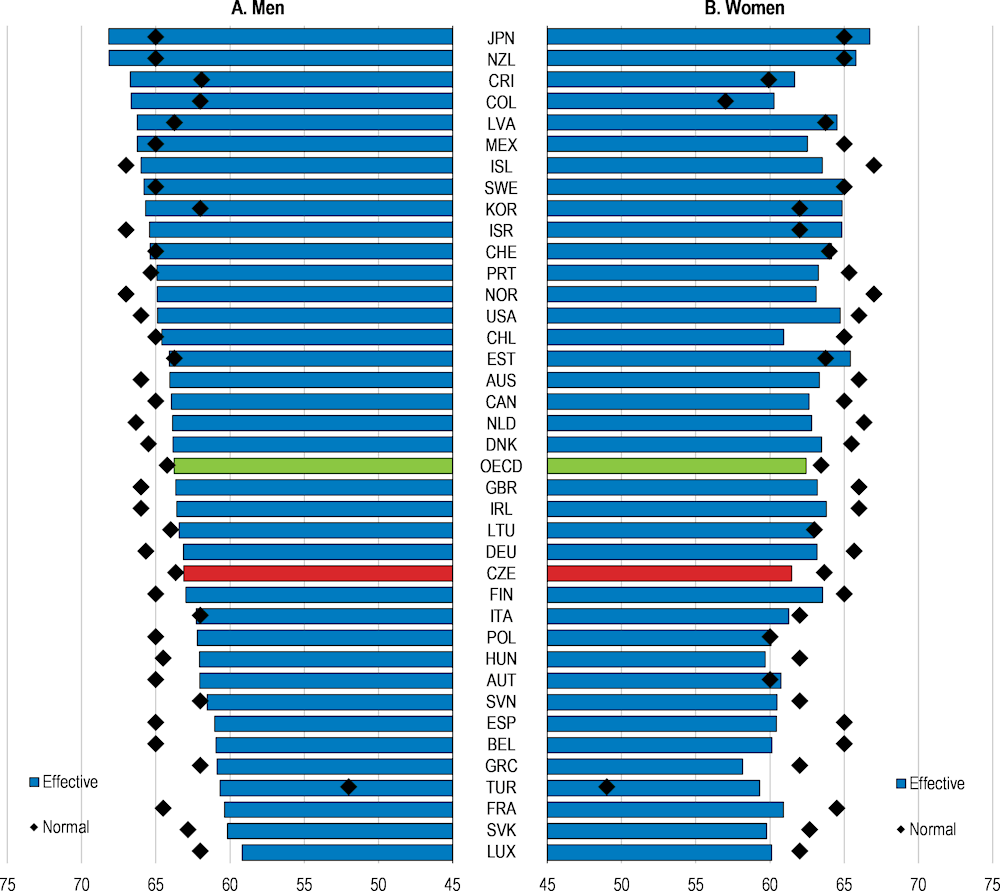

Czech workers retire too early. Currently, the effective age of labour market exit is among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 1.25). Employment – while high overall – falls sharply after the age of 60 to markedly below the OECD average (Figure 1.26). Rises in the statutory retirement age are already legislated. For men it will reach 65 in 2030. The Czech Republic is among the few OECD countries that still have gender-specific retirement ages, but the retirement age of women is also set to rise and will equal that of men in 2037, which is welcome. Yet almost one-third of people retire before the statutory retirement age (OECD, 2020b). Under current parameters, even once the statutory age of retirement will reach 65, early retirement will still be possible from age 60. The risk is that too many people might retire early, which would imply lower pensions.

Figure 1.25. The effective age of retirement is low

Average effective age of labour-market exit and normal retirement age, 2020

Note: Effective labour market exit age is shown for the six‑year period 2015‑20. Normal retirement age is shown for individuals retiring in 2020 after a full career from labour market entry at age 22.

Source: OECD (2021a), Pensions at a Glance 2021.

Figure 1.26. Employment rates fall sharply after 60

Employment rate, % of respective population, 2021

Adjusting the retirement age further is key to limit increases in pension spending and help maintain adequacy of benefits. In 2017, the automatic mechanism for increasing the statutory retirement age was withdrawn and the ceiling at the age of 65 was introduced. Every five years, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs is tasked to prepare a report on life expectancy and to suggest a shift in the statutory retirement age, provided that on average people spend a quarter of their life in retirement. Following the first report in 2019, no change ensued, and the next round is scheduled for 2024. Under this mechanism, the retirement age may not be increased in a timely and sufficient manner to curtail long-term spending pressures. The Czech Republic should (re)introduce a tight and automatic link between retirement age and life expectancy as has already been done in Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal. For example, if about two-thirds of gains in life expectancy are transmitted to increasing the retirement age, the balance between the time spent working and in retirement would be stabilised (OECD, 2020b). Under a similar rule, the Czech Fiscal Council (2021) estimates that linking the statutory retirement age to life expectancy would improve the balance of the pension system by 1.1-1.4% of GDP from 2050 and lower the debt-to-GDP ratio by 45 percentage points in 2071.

The minimum age of early retirement should also be increased in line with the statutory age, reaching at least 62 in 2030, and then be linked to life expectancy. Given longer life expectancy, the age of 60 for the future eligibility to early retirement is too low. This age reference contributes to shaping social norms and influencing behaviours by both employees and employers about working at older ages and is not consistent with other efforts to enhance the labour supply of older workers (OECD, 2020b).

Policies to delay retirement should be accompanied by labour market policies that foster employability, labour demand and incentives to work longer (OECD, 2019g). Currently, penalties and bonuses within the old age pension system discourage early retirement and incentivise deferred retirement. Yet, many retire early and only a few defer retirement (OECD, 2020b). It is likely that high replacement rates for low earners combined with the fact that older workers are less skilled and earn less than prime-age workers reduce incentives to work longer. According to the OECD Older Worker Scoreboard 2021, full-time earnings of older workers (55-64) in the Czech Republic are 5% below earnings of prime age workers, while in the OECD on average older workers earn 6% more. Raising the skills of older workers, through targeted adult learning, as recommended in the previous OECD Economic Survey (OECD, 2020a) could help promote longer working lives.

Table 1.7. Past recommendations on strengthening fiscal sustainability and improving the tax mix

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Shift taxation from labour towards real estate, consumption and environmental taxes. |

In 2020 a reform of the personal income tax dropped the concept of supergross wage. Property transfer tax was abolished. As a result, tax revenues are lower in structural terms by 2 percentage points of GDP. The reform was unfunded and part of it goes against the OECD recommendation. Phasing in of the electronic registration of sales was stopped and the project abolished. |

|

Reduce the advantages of self-employment in terms of social contributions and personal income tax. |

No action taken. |

|

Take steps to secure an increasing effective retirement age. Link tightly retirement age to life expectancy. Continue to ensure that the indexation of pensions does not lead to old-age poverty problems. Consider options for diversifying income sources for pensioners. |

No action taken. Government has recently taken steps to improve the adequacy of pensions by raising pensions beyond statutory required levels without addressing sustainability concerns. Government is supposed to discuss every five years whether to raise the statutory pension age (which is currently gradually rising to reach 65 in 2030 for men and in 2037 for women). In 2019, the government decided not to raise the statutory retirement age and to discuss the issue again in five years. |

|

Introduce a carbon component in energy taxation for carbon emissions outside the EU system. |

No action taken. |

|

Realign the excise tax rate on all fossil energy sources and products, based on their carbon content and other environmental externalities, notably by increasing the relative taxation of diesel. Remove several excise tax reliefs on fuel use. |

No action taken. |

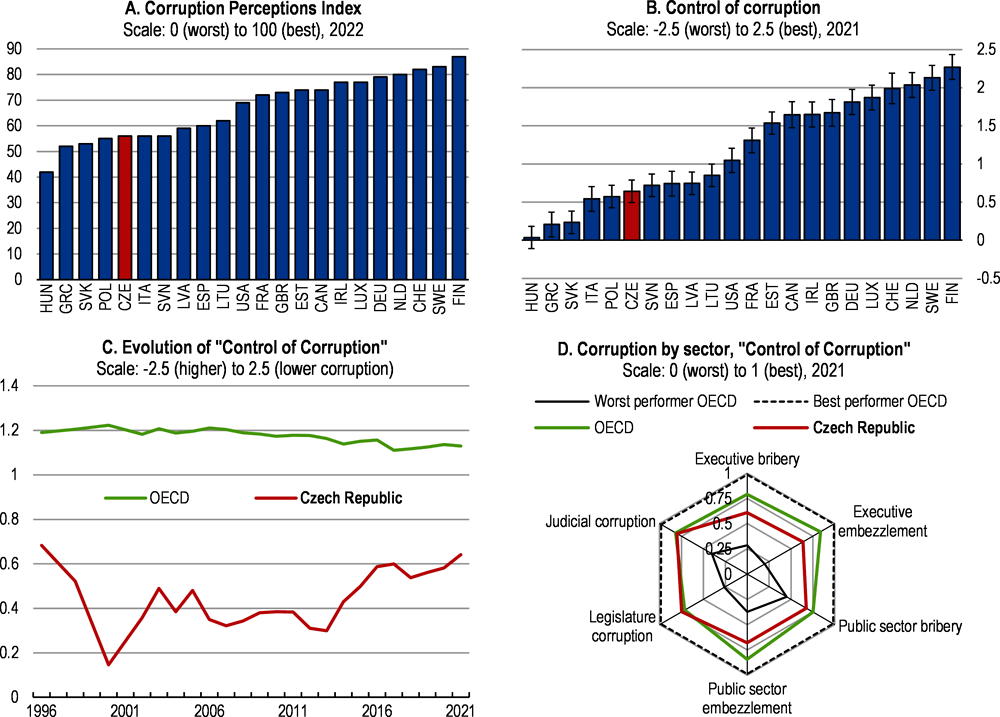

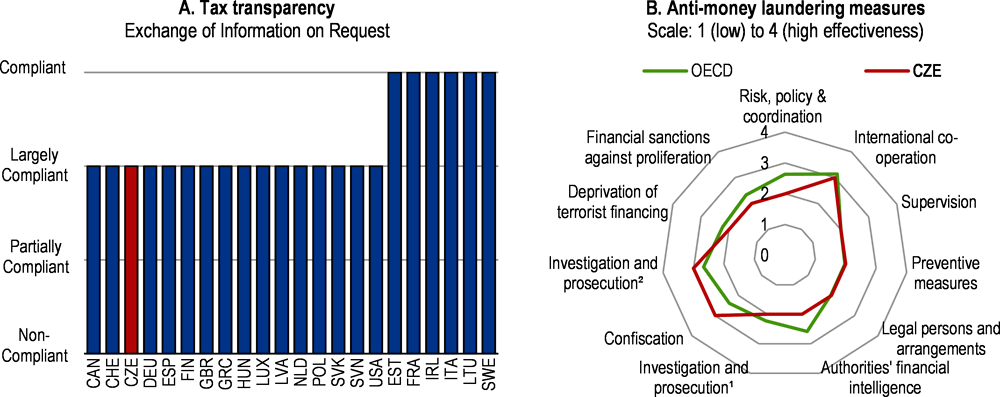

Raising the effectiveness of the public sector

Increasing the efficiency of public administration can help to improve fiscal sustainability and raise the quality of services provided to citizens. The size of the public sector in the Czech Republic has remained relatively moderate and stood below the OECD and EU averages in terms of general government expenditures (47% of GDP in 2020) and of employment (16.6% of total employment). However, despite its moderate size, the Czech public administration faces a number of challenges in modernising and improving its effectiveness. The Czech Republic has one of the most fragmented territorial and municipal administrations in the OECD (OECD, 2020a), undermining policy co-ordination between the national and subnational levels. The management of the COVID-19 crisis over 2020-21 also highlighted weaknesses in citizen engagement and in agility to respond to challenges.

The recent Public Governance Review done by the OECD in cooperation with the Czech government reports that the lack of strategic steering capacities and alignment from the centre have led to the multiplication of strategies and an absence of consistency and implementation across policies. Strategic decisions, regulations and policies are also insufficiently based on evidence. This calls for strengthening the strategic coordination of the Government Office and boosting analytical capacities across public administration.

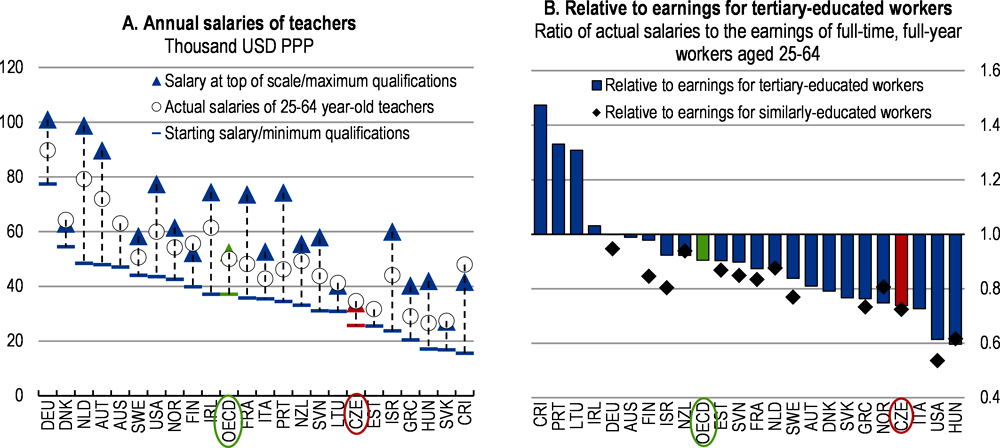

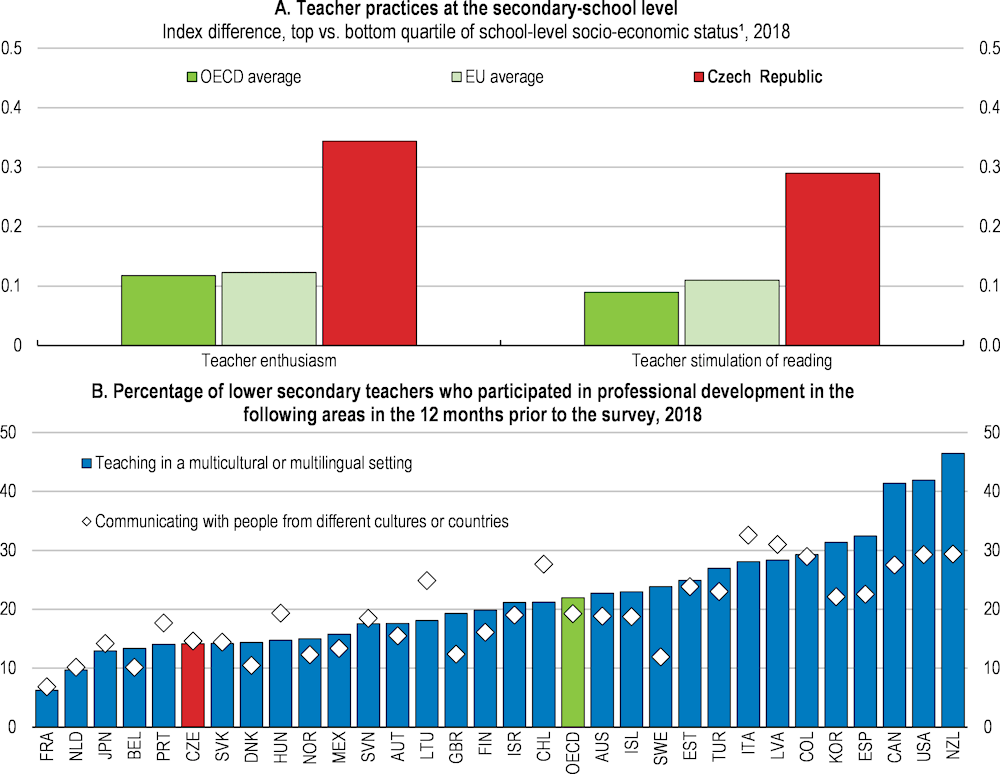

The Czech Republic has initiated a number of important public administration reforms to enhance the effectiveness of public administration, increase citizen orientation and engagement, and develop capabilities to address crosscutting challenges, including crisis management and digitalisation. Efforts have been made to improve analytical capabilities notably through the creation of a Government Analytical Unit in the Government Office. To accelerate its digital transition, the government is implementing a new digital governance structure including through the creation of a Digital Agency. The current public administration reform (PAR) strategy (“Client-oriented public administration 2030”) aims to address a number of challenges. At the same time more could be done to align the PAR strategy with current government priorities, particularly on raising effectiveness of public administration, improving management and recruitment within the civil service and strengthening cooperation between central and local government levels.