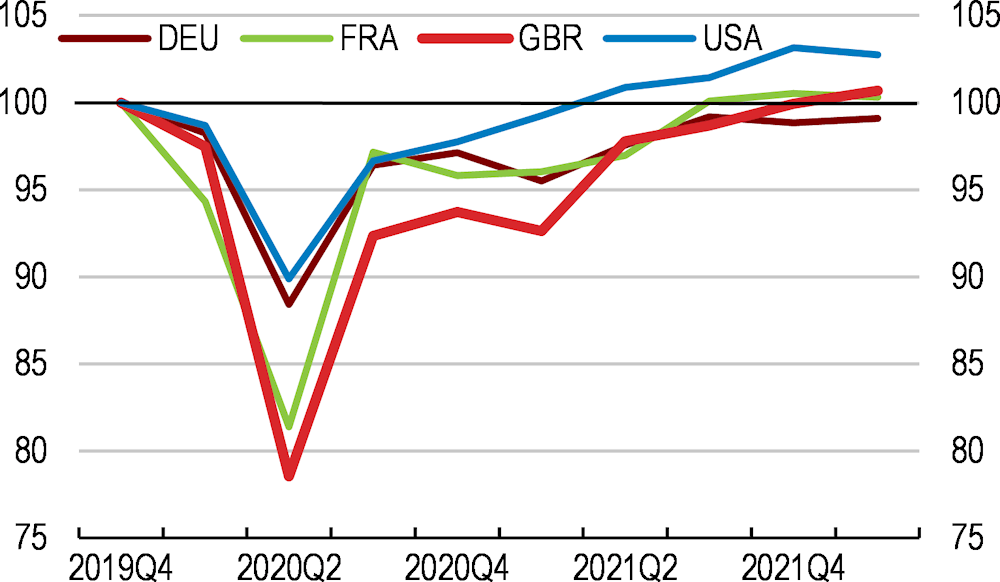

The UK economy recovered to the pre-pandemic level by the end of 2021, following an unprecedented contraction in 2020 (Figure 1). A quick vaccination rollout in 2021 allowed a gradual lifting of restrictions. As the economy started to recover at a rapid pace, supply and labour shortages worsened on the back of rising global demand and higher shipping costs. Price pressures rose significantly, aggravated by surging global energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Increased barriers to trade and migration resulting from leaving the European Single Market and Customs Union likely added to supply constraints. Amid persisting supply shortages and rising inflation growth has started to slow down.

OECD Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2022

Executive summary

The economy has recovered

Figure 1. The economy has recovered

Real GDP, 2019 Q4 = 100

The labour market rebounded quickly and job vacancies have reached record highs. Unemployment has fallen below pre-pandemic levels to 3.7%. Labour force participation has declined since the onset of the pandemic, mainly due to long-term sickness and early retirement by those aged above 55 years.

Trade in goods and services was negatively affected by Brexit and the pandemic. Non-tariff trade barriers with the EU have increased administrative costs. Trade with the EU has recovered somewhat after a sharp drop at the end of the transition period in January 2021, but imports from the EU remain suppressed.

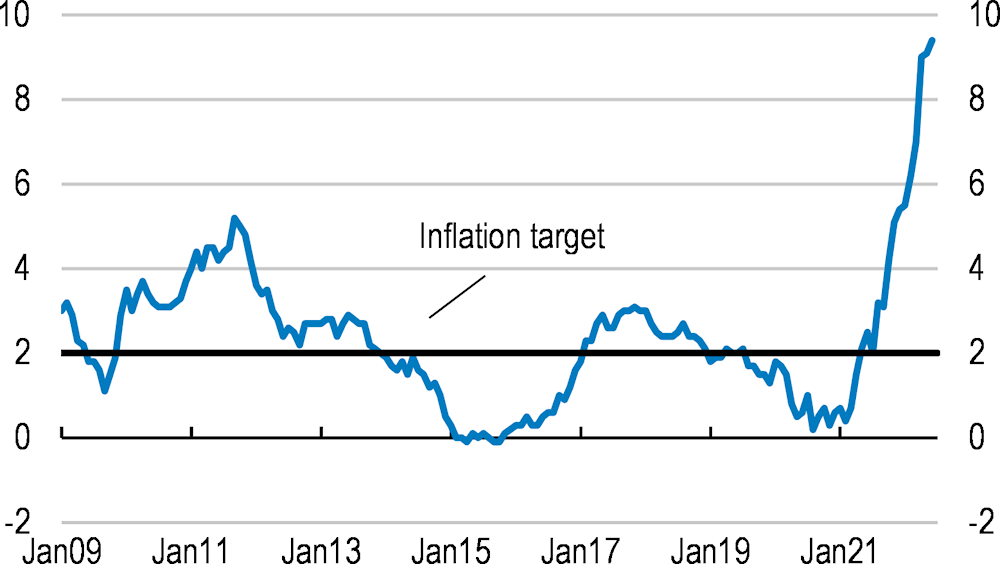

Monetary policy has been normalising on the back of rising inflation pressures (Figure 2). In response to rapidly rising inflation and a tightening labour market, the central bank has gradually increased the policy rate since December 2021 from 0.1% to 1.25% in June, ended asset purchases, stopped reinvesting maturing gilts, and announced the gradual selling of its stock of corporate bonds. A winding down plan for the stock of government bonds will be discussed in August 2022.

Figure 2. Inflation is rapidly rising

Headline inflation (CPI), y-o-y % changes

Fiscal policy has to balance fiscal tightening with supporting growth and investment needs. The government has committed to a gradual medium-term fiscal consolidation plan, with planned increases in tax revenues and increased investment. As cost of living has risen sharply, the government introduced temporary and targeted support measures to aid vulnerable households. The government is on track to reach its new fiscal target, which will put net debt on a declining trajectory. In the longer run, the United Kingdom faces significant fiscal pressures mostly driven by ageing related expenditure and transitioning to net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

The financial sector weathered the pandemic well, and banks hold substantial provisions against future credit losses. Risks from the mortgage market remain contained but rapid house price growth warrants continuous vigilance. Well-developed capital markets and a sound banking system are expected to facilitate the required reallocation of capital as a consequence of Brexit, the pandemic and net zero transition but the long-term impact on the UK financial sector remains unclear.

Table 1. Economic growth will slow

(Annual growth rates, %, unless specified)

|

|

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gross domestic product |

7.4 |

3.6 |

0.0 |

|

Private consumption |

6.2 |

4.5 |

0.7 |

|

Government consumption |

14.3 |

1.4 |

0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

5.9 |

8.0 |

2.1 |

|

Exports |

-1.3 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

|

Imports |

3.8 |

15.7 |

3.6 |

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

4.5 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

|

Consumer price index |

2.6 |

8.8 |

7.4 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

-2.6 |

-7.2 |

-7.6 |

|

Government fiscal balance (% of GDP) |

-8.3 |

-5.3 |

-4.1 |

|

Government gross debt (% of GDP) |

143.1 |

139.2 |

138.6 |

Source: OECD Economic Outlook (database).

Output growth is projected to weaken in 2022 and 2023 (Table 1), as rising living costs weigh on consumption. Business investment will be dampened by rising interest rates and lingering uncertainties. A deterioration in the public health situation and spill-overs from economic sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are significant downside risks to the outlook.

Raising productivity

Productivity growth has stalled since the Global Financial Crisis on the back of skill mismatches, low innovation and knowledge diffusion, as well as low investment. Productivity gaps are wide across regions.

Regional disparities weigh on aggregate productivity growth. “Levelling up the UK“ in terms of productivity and living standards is a key policy priority of the government, but the additional funding announced so far has been limited. Local authorities face a fragmented and complex funding landscape, challenging to navigate for local authorities, risking that capacity constrained local areas miss out on needed funding.

Better infrastructure is key to stronger productivity growth. Public investment has increased in recent years and will remain close to a significant 2.5% of GDP over the coming years under the government’s Plan for Growth. However, large investments will be needed to compensate for years of underinvestment and to address long-term challenges such as the net zero transition.

Higher private investment is needed to support productivity growth. Business investment in physical capital, innovation or new processes that would make labour more productive has been subdued due to uncertainties following Brexit and the pandemic.

Skill shortages weigh on productivity. Increasing digitalisation and transitioning to net zero will require intensifying adoption of new technologies. This implies an ever-growing need for workers to update their skills, but participation in continuing education and training is low.

More fully utilising women skills in the labour market would support productivity and growth. A third of women work part-time, roughly three times more than men. Mothers are likely to reduce working hours following childbirth. Parental leave for fathers is short and combined with low female pay replacement rates and a relatively high out-of-pocket price for childcare contributes to gender gaps in labour participation and earnings.

Reaching net zero

The United Kingdom has successfully reduced greenhouse gas emissions in the past, and a broad political consensus supports the target to reduce net emissions to zero by 2050. The UK’s strong institutional framework is an inspiration to countries around the world, and the country is pioneering work to embed climate considerations in the financial sector.

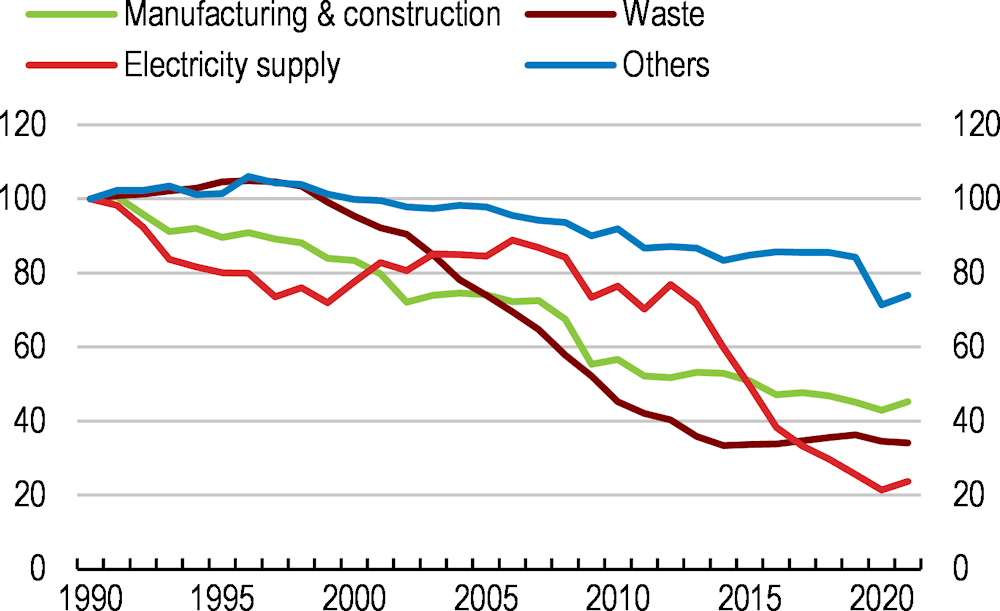

Achieving carbon neutrality will require policy to match ambition. Emission reductions so far were largely driven by electricity generation, a sector targeted by the emission trading scheme (ETS), a carbon price floor and a cost efficient renewables auction-design subsidy scheme. A landfill tax and the ETS also drove down emissions in other sectors (Figure 3). Expanding pricing instruments across the economy is an essential building block to reach targets, but well-designed sectoral regulation and subsidies are also needed to boost innovation and overcome a number of hurdles. A clearer transition policy path would allow the financial sector to better support the green transition.

Figure 3. Sectors with an explicit carbon price drove past emission reductions

Greenhouse gas emissions by sector in the UK, index 1990 = 100

Note: “Others” include buildings, surface transport, agriculture, land use and forestry, f-gases and aviation and shipping (including international aviation and shipping as defined in UK climate targets).

Source: Climate Change Committee, 2022 Progress Report to Parliament.

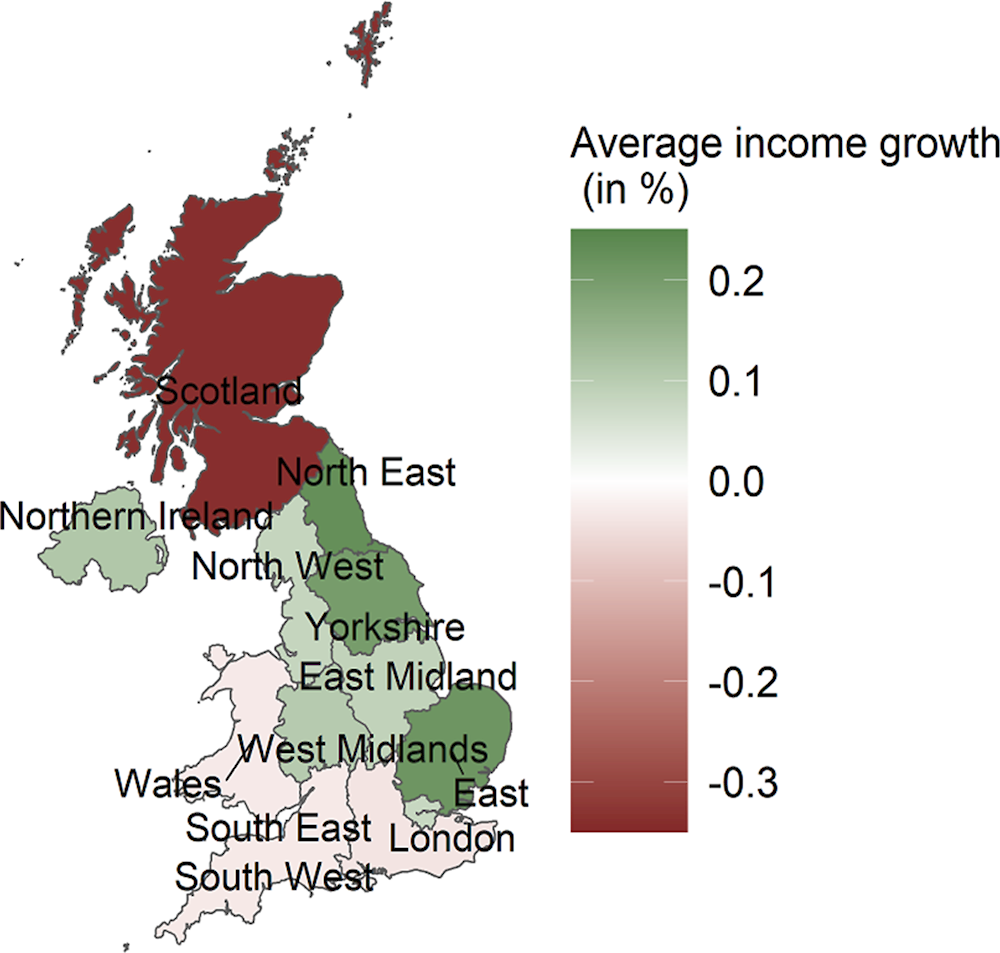

Britons are conscious about the need to act, but do not necessarily support efficient policies like carbon pricing. This reflects that efficient climate policies will reduce incomes more among less affluent people and those living in sparsely populated areas (Figure 4), unless they are compensated or supported to reduce fossil fuel dependence. Climate change reducing measures will be more acceptable when implemented once energy prices have started to normalise following the current historical high.

Figure 4. Carbon pricing affects regions differently

Note: Income growth from a carbon tax combined with redistributing 30% of revenue as a lump-sum transfer, computed as the average growth in income by decile.

Source: Pareliussen, Saussay and Burke, forthcoming (2022).

Recycling revenue to support clean technologies and infrastructure increases popular support for direct pricing instruments. Transfers and programmes to support energy efficiency, notably for low-income households, can minimise unwanted distributional effects and strengthen energy security.

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|

|

Supporting a sustainable recovery |

|

|

The economy has recovered to pre-pandemic levels. High energy prices and rising cost of living are slowing growth. Monetary policy has started to tighten as inflation increased sharply and persistently. |

Continue to progressively raise the Bank Rate to ensure the return of inflation to target, while taking into account any significant changes in economic conditions. |

|

The pandemic and leaving the EU Single Market and Customs Union have weighed on trade. Non-tariff trade barriers with the EU increase administrative costs. Services account for a large share of trade, but the UK-EU agreement focuses mostly on goods. |

Discuss with the European Union to reduce non-tariff barriers for EU-UK trade in goods and improve mutual market access for services. |

|

Addressing fiscal challenges |

|

|

Following the phasing out of extensive COVID-19 support measures, fiscal policy has to balance fiscal tightening with supporting growth and meeting significant investment needs. |

Gradually lower the fiscal deficit and the public debt-to-GDP ratio as planned while ensuring temporary support through income transfers is targeted at low-income households. |

|

Fiscal targets are changing frequently. The government has introduced new fiscal rules and targets in 2021, providing clear guidance about the medium-term plan for returning to debt sustainability. The government announced that its fiscal rules will guide its policy for at least this Parliament and will be reviewed at the start of each subsequent Parliament. |

Ensure that future changes to fiscal targets follow a regular process to support credibility of fiscal policy. |

|

In the longer term, fiscal space is pressured by ageing related spending pressures and decreasing fiscal revenues as the economy is transitioning to net zero carbon emission. |

Replace the state pensions triple lock by indexing pensions to an average of CPI and wage inflation and provide direct transfers to poor pensioners to mitigate poverty risks. |

|

Raising productivity |

|

|

Productivity growth has been sluggish since the Global Financial Crisis. Under an ambitious Plan for Growth, large scale investments in infrastructure, skills and innovations are planned, but investment needs are large. Aggregate productivity is weighed down by regional disparities. |

Continue ambitious public investment as planned, and implement existing Levelling Up White Paper proposals to ensure it is well targeted, better streamlined, and with a special focus on improving productivity in lagging regions. |

|

Local authorities face a fragmented funding landscape, which the 2021 Levelling Up White Paper committed to streamline and simplify. Poorer areas have not benefited to the same extent from the allocation of the first round of the new Levelling Up Fund. |

Identify and reduce barriers to access funds for local authorities and provide capacity building measures to ensure lagging regions make use of available funds. |

|

Business investment has been slow on the back of Brexit and pandemic related uncertainty, contributing to low productivity growth. |

Ensure long-term policy transparency and continuity of government programmes to reduce uncertainties for businesses. |

|

The transition to net zero will provide new job opportunities and require new skills. Adding to existing skill-shortages, quickly rising demand for skills requires the need for re- and upskilling of the exiting workforce. |

Use statistical tools to target training to low skilled workers affected by digitalisation and the green transition to strengthen their skills to transit to new jobs. |

|

Women are highly educated but their skills are not fully utilised in the labour market and inequalities in earnings persist. Women adjust working hours to take over care responsibilities. Parental leave pay rates are low, providing little incentives to shift leave to fathers. |

Increase funding to reduce the cost of good-quality childcare, in particular for under 2 year olds, giving priority to low income households. Increase the cap on paternity pay and relate it to father’s income. |

|

Reaching net zero |

|

|

Achieving carbon neutrality will require policy to match ambition. Uncertainty regarding future policy stringency holds back investments. |

Build on the Net Zero Strategy, with further concrete deadlines, policies and priorities in line with legal targets. |

|

Private incentives to reduce emissions are inconsistent across sectors and energy sources and too low in a number of sectors, including emission removals. |

Commit to gradually expand the UK ETS to all emitting sectors and tighten the emissions cap in line with targets. |

|

Carbon pricing and regulation will in the absence of flanking policies hit low-income households, those in rural areas and those with high heating needs disproportionately at the risk of triggering public resentment. |

Allocate a portion of carbon pricing revenues to schemes compensating low-income and fuel-poor households and supporting their green investments. |

|

Recycling revenue to support clean technologies and infrastructure increases popular support for direct pricing instruments. |

Allocate a portion of carbon pricing revenue to public investment in green infrastructure, development and deployment of green technologies, including carbon capture and storage. |

|

Different biases and constraints prevent households from making climate-friendly investments in heating, energy efficiency and transportation even when they are profitable. Plans for regulatory back-stops exist, but they need to be translated into concrete policies spurring early action. |

Target households’ energy use with well-designed regulations phasing in higher energy efficiency, clean heating and zero-emission vehicles. |