The United Kingdom recovered from the economic shock from the COVID-19 pandemic owing to emergency support packages put in place and a rapid vaccine rollout. However, growth is slowing amid persisting supply shortages and rising inflation. Fiscal policy has to balance gradual tightening with providing well-targeted and temporary support to vulnerable households from rising costs of living, supporting growth and addressing significant spending and investment needs. Accelerating progress towards net zero is fundamental to enhance energy security and reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Policy reforms to support economic reallocation and investments in the green and digital transition can stimulate productivity growth and contribute to reducing disparities across UK regions.

OECD Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2022

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The pandemic and Brexit have magnified structural challenges

The United Kingdom is recovering following the heights of the COVID-19 pandemic. After being severely hit by the pandemic, a quick vaccine rollout in 2021 improved the public health situation and allowed the easing of containment measures. As the economy started to recover in 2021 at a rapid pace, labour shortages intensified on the back of rising global demand and global supply constraints. Price pressures rose significantly, aggravated in early 2022 by surging global energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Increased barriers to trade and migration resulting from leaving the European Single Market and Customs Union on 1 January 2021 likely added to supply constraints. Amid persisting supply shortages and rising inflation, growth has started to slow down.

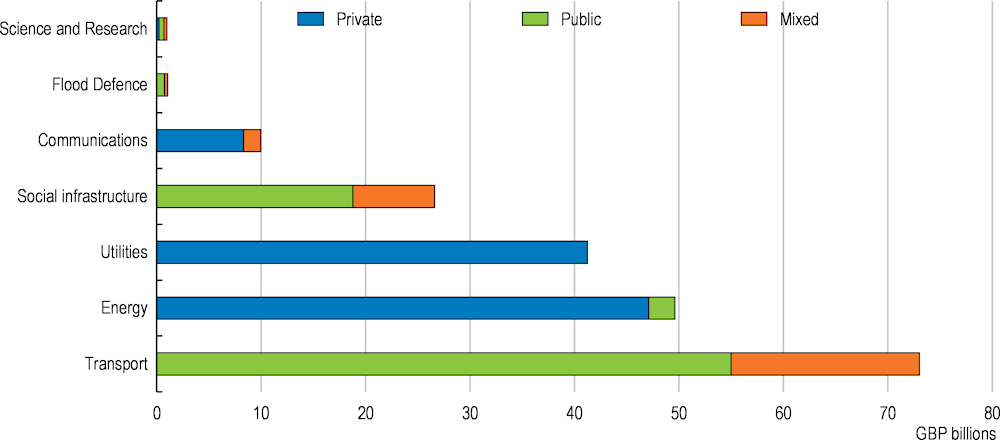

As the immediate impact of the pandemic subsides, the policy focus should shift to addressing long-standing structural challenges that have been magnified by the pandemic and Brexit. The United Kingdom entered the pandemic with weak productivity growth, large regional disparities and an ageing population. Years of underinvestment in public infrastructure resulted in large investment needs. The decade of strong fiscal consolidation ended with the provision of extensive fiscal support during the COVID-19 crisis, which helped to attenuate the loss of household income and allowed businesses to survive (Figure 1.1). However, public debt has increased considerably, calling for a gradual fiscal tightening while also bringing the need to raise productivity and growth to the fore.

Figure 1.1. Fiscal support during the pandemic supported households and businesses

Note: The colour scale of the background reflects confinement stringency based on the Oxford Stringency Index. The Oxford Stringency Index is a composite measure based on 9 response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest response). Panel A: Cumulative job retention scheme spending. Panel B: Registered company bankruptcies. COVID-19 business loan schemes are the cumulative sum of the total value of loans of the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS), Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CLBILS) and Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS). Figures for CBILS, CLBILS and BBLS are based on management information supplied to HM Treasury by accredited lenders and represent their best estimates of the published totals. The value of BBLS loans approved includes extra value from BBLS loans that have subsequently been ‘topped-up’. As of 31 May 2021, 106,660 BBLS top-ups had been approved worth GBP 0.95 billion. Data on the recovery loan scheme are missing as they are not available yet with the time dimension.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Projections and Statistics database; UK government, Coronavirus job retention scheme Statistics: December 2021; UK Government, Monthly Insolvency Statistics December 2021; UK Government, HM Treasury coronavirus business loan scheme statistics; and Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government.

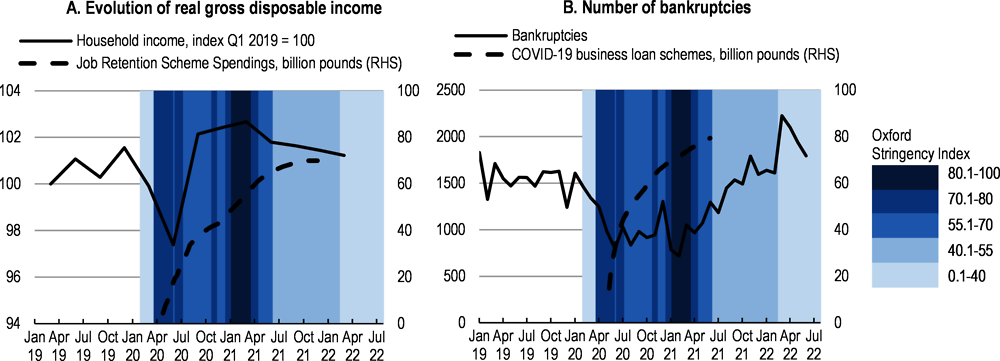

Population ageing, aggravated by potentially lower net migration following Brexit, requires the efficient use of resources to maintain economic growth (Figure 1.2, Panel A). Productivity growth has been almost stagnant over the last decade and is lower than in many other advanced OECD economies (Figure 1.2, Panel B). COVID-19 and leaving the European Union Single Market continue to cast their shadows on the economy. Estimates by the UK Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) suggest that, due to the pandemic, potential output by 2025 will be 2% lower than pre-pandemic trends on the back of higher inactivity rates among older workers, lower net migration, foregone investment, and lower total factor productivity. In addition, the OBR estimates that Brexit will lead to 4% lower productivity after a 15-year period, relative to remaining in the European Union, due to a fall in trade intensity.

Figure 1.2. An ageing population meets low productivity growth

Note: Panel A: Old age dependency ratio is the number of individuals aged 65 and over in relation to the working aged population (25-65 years). Panel B: Labour productivity is measured as GDP per hour worked at constant prices, USD purchasing power parities.

Source: ONS; and OECD (2022), productivity database.

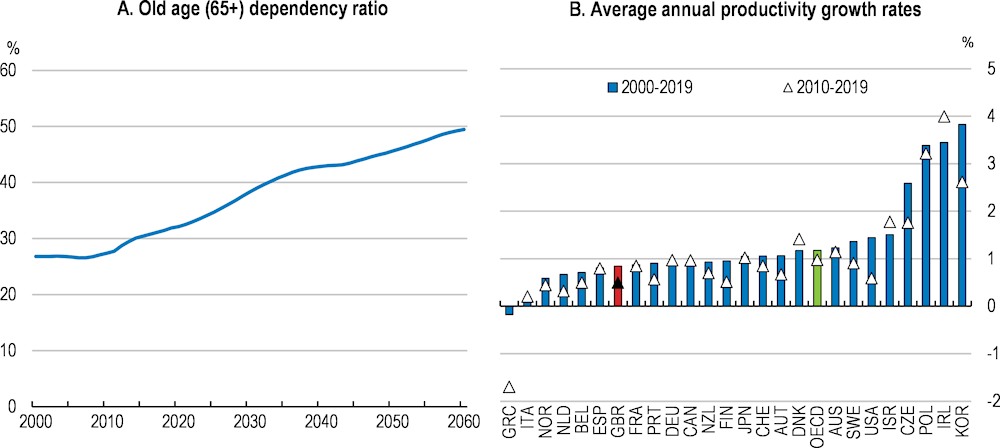

Inequalities in income and wealth were already higher than in most OECD countries before the COVID 19 crisis (Figure 1.3), but have increased further since. In addition, disparities in income, work, education and health are high across UK regions (Figure 1.3). The COVID-19 pandemic also opened up new gaps among people and businesses along dimensions that were previously less significant, such as the ability to work from home and digital access. A highly unequal distribution of skills and qualifications is not only hampering social mobility but has also been contributing to regional disparities, with a concentration of low skills in the least productive regions. Raising productivity and living standards in lagging regions is at the heart of the government’s “Levelling Up” agenda and will require significant public and private investment.

Figure 1.3. Income inequality and regional disparities are high

Regional-Wellbeing, 0-10, 10 indicating higher performance relative to other regions (including inequality measures)

Note: The following indicators are used to construct the different indices by topic as appearing in the figure starting from Education: Labour force with at least secondary education (2017), Employment rate and unemployment rate (2017), Household disposable income per capita (2016), Homicide rate (2016), Life expectancy at birth (2016) and mortality rate (2016), Air quality: PM2.5 (2015), Voter turnout (2015), Share of households with broadband access (2017), Rooms per person (2011), Perceived social network support (2014), Self-assessment of life satisfaction (2014). National data is used for Gini after taxes (2019 or latest), S20/s80 ratio (2019 or latest), share of top 5% of wealth (2019 or latest) rescaled using the min-max formula. OECD aggregate refers to a simple average over countries for which data was available. Latest data available are used for more info see source.

Source: OECD Regional Well-Being database.

The United Kingdom needs to address its long-standing structural challenges to better weather the deep transformations that it is rapidly undergoing. COVID-19 has sped up digitalisation and people are more likely to work and shop from home. Faster digitalisation and the adoption of new technologies imply an ever-growing need for workers to update their skills to meet new skill requirements. Leaving the EU Single Market and Customs Union resulted in restricted access to the United Kingdom’s largest trade and investment partners, calling for a new trade strategy. The United Kingdom is committed to become a net zero greenhouse gas emission economy by 2050. CO2 emissions per unit of GDP have fallen more rapidly in the United Kingdom than elsewhere in the OECD, but continuing the path to net zero will be considerably more challenging in the years to come. Significant investment needs to decarbonise the economy will reduce fiscal space and will require considerable policy changes affecting businesses and people’s daily lives. Changes will affect sectors, regions and population groups to varying degree and at different times, but the required labour and capital reallocations across sectors will be challenging.

Against this background, this Survey discusses policies to consolidate a sustainable and inclusive recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and to adapt to the economic transformations that Brexit and the transition towards net zero by 2050 require. The main policy messages of the Survey are:

Following the government’s strategy, fiscal policy has to balance gradual fiscal tightening with supporting growth, providing well-targeted and temporary support to protect vulnerable households from high costs of living and addressing significant spending and investment needs to support on-going economic transformations.

Raising productivity will be key to enhance growth and reduce inequalities across regions. This will require sustained increases in public investment as planned and a substantial rise in private investment. Significant re- and up-skilling are needed to support workers’ reallocation and address current and future skill-shortages.

Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 calls for timely, coherent and efficient policies across all sectors of the economy, addressing sector-specific market failures, competitiveness and distributional concerns heads-on.

The economy is recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, bringing challenges from leaving the EU to the forefront

Economic growth has slowed after a strong recovery

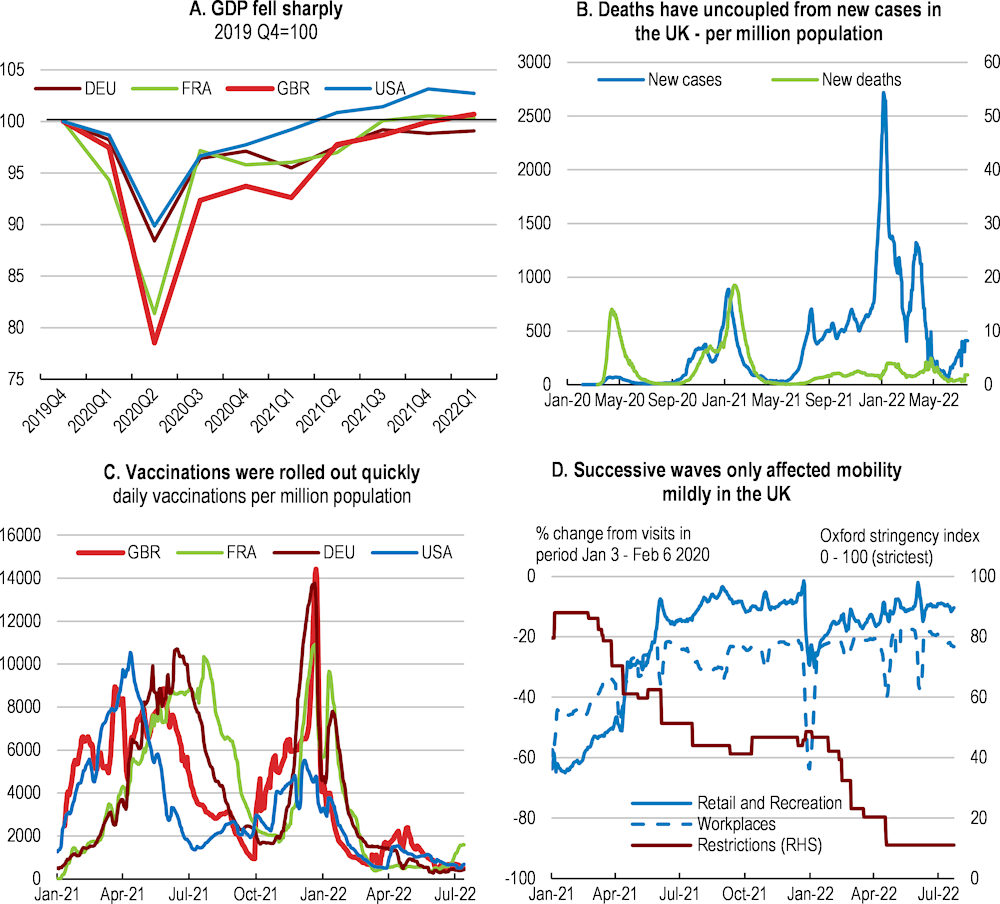

The economy has rebounded following an unprecedented contraction during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1.4, Panel A), aided by timely government support measures as described in the last Economic Survey (OECD, 2020[1]). As in other OECD countries, the United Kingdom experienced several waves of COVID-19 infections, but a fast initial roll-out of vaccines over the first half of 2021 weakened the link between new COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths since summer 2021 (Figure 1.4, Panels B and C). With an improved public health situation, COVID-19 related restrictions were gradually eased from April 2021 and economic activities started recovering (Figure 1.4, Panel D). To keep the recovery on track, the government should ensure that the public health situation remains under control by continuing its vaccination efforts in line with international guidance.

Figure 1.4. GDP has recovered on the back of an improved health situation

Note: COVID-19 figures were last updated on 27 July 2022. Panel A: The UK Office for National Statistics is one of the few major National Statistical Institutes to follow the volume indicator approach for most health and education outputs, which is recommended by the European System of National Accounts. This different statistical method may have led to some divergence in reported output declines during the pandemic, but the return to normal should reverse such divergence (see OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2021 Issue 1, box 1.1 for more details); Panel B: New cases are new confirmed cases of COVID-19 (7-day smoothed) per one million people. New deaths are newly confirmed deaths of COVID-19 (7-day smoothed) per one million people.

Source: OECD (2022), Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database; Hale et al., (2022). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government; Google LLC, Google COVID19 Community Mobility Reports; and Roser et al (2022), "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Published online at OurWorldInData.org.

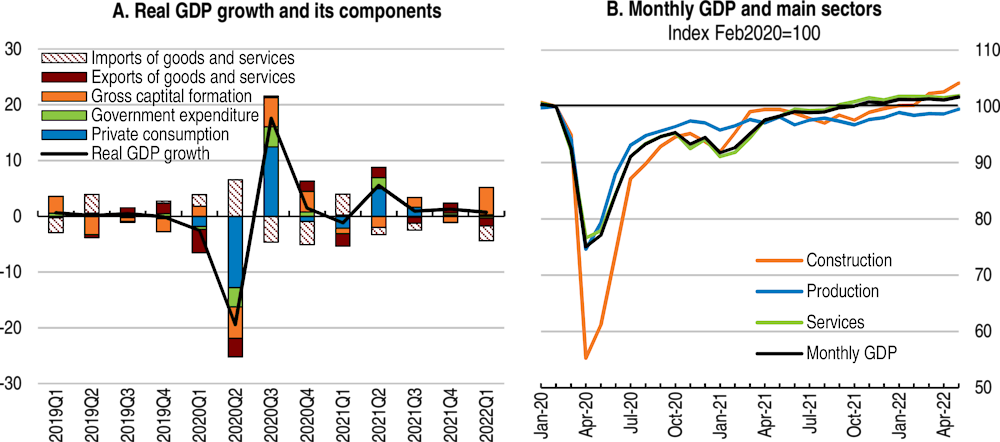

Output recovered to pre-pandemic levels by November 2021, but growth slowed from 1.3% in the last quarter of 2021 to 0.8% in the first quarter of 2022 (Figure 1.5, Panel A). Important sectoral differences remain. The construction sector, heavily affected by the pandemic, was the quickest to recover, reaching pre-pandemic levels by the end of April 2021 (Figure 1.5, Panel B). By beginning 2022, the service sector exceeded pre-pandemic levels, but consumer-facing services, most affected by containment restrictions, still remained 5% below pre-pandemic levels by May 2022. Production output has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels, as early improvements from mid-2020 have slowed due to labour shortages and global supply issues.

Figure 1.5. The economy recovered to pre-pandemic levels

The United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union Single Market and the pandemic weigh on trade

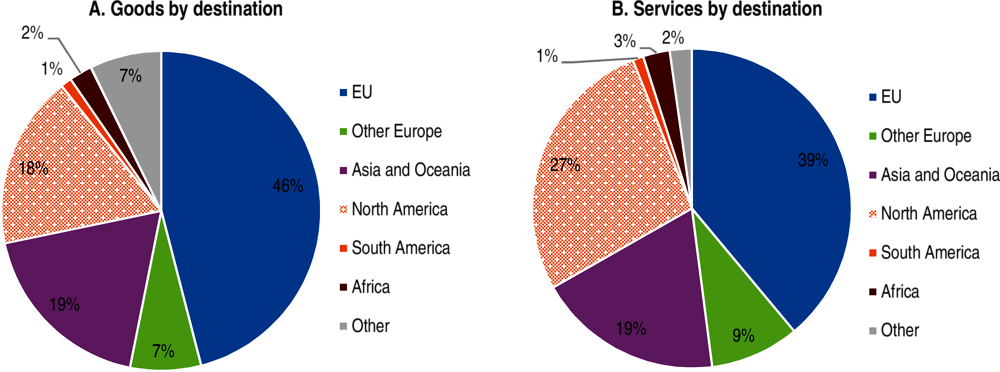

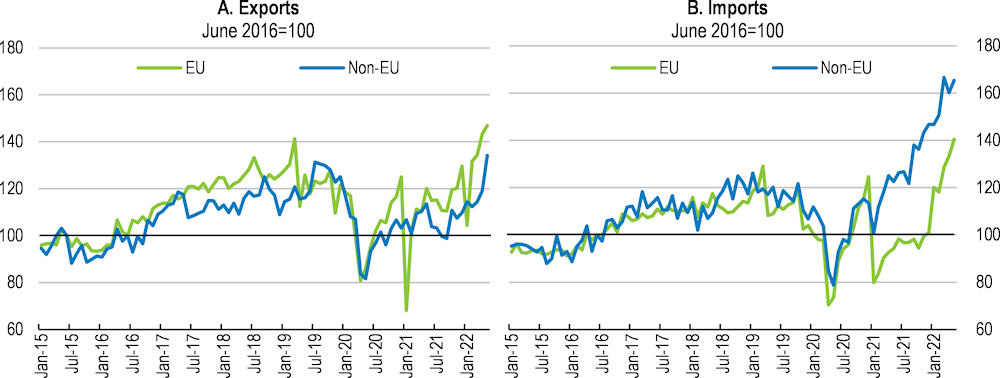

Trade has not only suffered from supply bottlenecks and suppressed demand during the pandemic, but also from increased trade frictions with the European Union owing to Brexit (Box 1.1). The European Union was the destination of 46% of UK’s goods exports and 39% of services exports and the origin of 49% of both goods and services imports in 2019 (Figure 1.6). Trade in goods with the European Union dropped sharply in January 2021, when the transition period ended, and the United Kingdom effectively left the EU Single Market and Customs Union (Figure 1.7). Since then, trade flows have recovered somewhat, especially UK exports to the European Union. However, recent analysis suggests that the number of trade relationships dropped by one third after January 2021, as trade costs due to administrative burden increased (Box 1.2Figure 1.6). While large firms that drive aggregate exports have not yet been severely affected, increased fixed cost have curbed the ability of smaller firms to export (Freeman et al., 2022[2]). Recent interventions to provide SMEs with export support are welcome and should be sustained. Imports from the European Union remain depressed as increased trade costs lead to both UK import activity shifting away from the European Union and EU firms for which the UK market accounts only for a small share of sales reducing exports to the United Kingdom. Services exports and imports declined during the pandemic, with imports from the European Union decreasing the most.

Figure 1.6. The European Union is a major trading partner

Share of exports by sector and destination, 2019

Figure 1.7. Leaving the EU Single Market has affected imports more than exports

Note: Goods imports and exports exclude precious metals. In January 2022 there have been changes to the way HM Revenues and Customs (HMRC) collect data for both imports from and exports to the EU; because of these changes caution should be taken when interpreting these data.

Source: ONS, UK trade: goods and services publication tables.

The TCA has clarified the post-Brexit trading relationship between the United Kingdom and the EU. Some uncertainties around the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) remain, in particular about implementing the Northern Ireland Protocol (Box 1.1). To support exports to the EU market, the United Kingdom and the European Union should discuss to reduce non-tariff barriers for EU-UK goods trade and improve market access for services. The further phase-in of checks on goods imported from the European Union will continue from next year (2023), including additional sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) checks, and its impact on trade flows should be monitored closely. Access to comprehensive export support services, especially for SMEs, should continue to be provided (Table 1.1) while targeted support to firms and workers that may suffer from trade frictions could be considered.

Box 1.1. The Withdrawal Agreement, Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the special trade status of Northern Ireland

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The United Kingdom and European Union agreed on a comprehensive Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in 2020 that entered into force on 1st January 2021. The TCA allows for zero-tariff, zero-quota trade in goods between the United Kingdom and the European Union. Although comprehensive in scope as a free trade agreement, it entails significant trade frictions for UK based goods and services exporters. While it guarantees tariff-free access for goods trade, non-tariff technical barriers such as sanitary and phytosanitary requirements and rules of origin are not addressed. The agreement is more limited with regards to services, introducing non-tariff barriers and reduced access to the Single Market and very limited provisions on financial services. The level-playing field provisions in the TCA imply that trade restrictions could be introduced by either side in case of significant divergence in areas such as labour, climate or subsidy policy.

The special trade status of Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Protocol is part of the Withdrawal Agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union. Agreed on 17 October 2019, with provisions applying from 1 January 2021, it arranges the rules for cross-border flows of goods, services and migration between the European Union (i.e., the Republic of Ireland) and Northern Ireland. In light of protecting the peace process and the 1998 Belfast agreements, the intent has been to prevent a hard or soft border between the European Union and Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Protocol in the Withdrawal Agreement effectively leaves Northern Ireland as part of the Single Market, avoiding the need for a border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic. Northern Ireland hence needs to align itself with Single Market rules with regard to trade in goods. To preserve the integrity of the Single Market, it was agreed that some checks will be required at the sea border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. Although the agreement benefits Northern Ireland as it gives full access to the EU Single Market, trade with Great Britain has experienced frictions.

On 13 June, the UK government introduced a new bill in parliament that would enable it to unilaterally disapply elements of the Northern Ireland Protocol in the United Kingdom. The bill would empower ministers to introduce changes in four areas of the protocol, covering customs and food safety checks, the application of EU regulations, VAT changes and the role of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). The government’s stated aim is to facilitate trade destined for Northern Ireland from Great Britain by reducing custom checks on goods crossing between the two. Before coming into effect, the bill has to be debated and voted on in parliament. The UK government has stated that its preference remains finding a negotiated solution with the EU. The publication of the new bill adds to uncertainty for businesses in Northern Ireland, potentially affecting trade and investment.

Source: UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, October 2019; UK government, Northern Ireland Protocol Bill 2022.

The UK government is developing a new trade strategy. Having left the European Union and its trade framework, the United Kingdom has replaced the EU external tariff with a new “UK global tariff” under which the number of goods with zero tariffs increased. The openness to services trade has further improved as evidenced by an improved score on the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, bringing the UK in fifth position out of 38 OECD countries. The UK has also concluded continuity agreements with almost all countries that had trade agreements with the European Union at the time of exit, as well as new agreements with Japan, the EFTA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland), Australia and New Zealand. The United Kingdom maintains an interest in a trade agreement with the United States, but has recently shifted attention toward the Indo-Pacific region to benefit from its growth potential (Department for International Trade, 2021[3]). The United Kingdom is also in the accession process to become a member of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and is negotiating an agreement with India, aiming to reduce barriers for goods and services trade.

The new trade agreements the United Kingdom has finalised so far are unlikely to make up for the loss of EU export market shares. Reduced trade frictions between the United Kingdom and the CPTPP countries and India may boost UK exports in the longer run, but will have a modest impact in the short term as they respectively accounted for just over 8% and 1.5% of UK exports in 2017-2019 (Hale, 2022[4]). Furthermore, the United Kingdom will be competing for these export markets against existing members such as Canada and Japan. A deep trade agreement with the United States could give the United Kingdom exports a bigger boost in the near term, as exports to the United States accounted for 20% of total exports in 2019. In addition to facilitating UK exports to the EU, the government should continue to negotiate new trade deals with other partners. The long-term economic impact of Brexit remains uncertain and will depend on multiple factors including the streamlining of global supply chains in response to Brexit (and the pandemic), access to the EU Single Market, regulatory divergence to the European Union, the relative attractiveness of the United Kingdom driven by policy choices in the United Kingdom and abroad and the number and nature of the UK’s new trade agreements.

Box 1.2. The administrative costs of EU-Great Britain goods trade post Brexit

Trade between Great Britain and the European Union faces a range of customs requirements since the UK departure from the EU.

All goods will require:

Customs declarations;

Customs duties for goods that do not comply with preferential rules of origin;

Import VAT;

Safety and security declarations.

Some goods need additional checks:

Checks required by international conventions such as endangered species;

Sanitary and phytosanitary checks including documentary, identity and physical checks;

Excise duties.

Source: Institute for Government (2022[5]).

Table 1.1. Past recommendations on international trade

|

Recommendation in previous Surveys |

Actions taken since last Survey |

|---|---|

|

Keep low barriers to trade and investment with the European Union and others, particularly market access for the service sectors including financial services |

The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement entered into force on 1 January 2021. It allows quota and tariff free trade for goods but introduces a range of technical barriers, whilst there is a more limited number of provisions regarding services within the TCA. |

|

Enhance communication on a no-deal exit from the European Union |

A no-deal exit was avoided with the conclusion of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. |

|

Prepare targeted support to firms and workers that may suffer the most. |

SME Brexit support fund launched in February 2021 offering up to GBP 2 000 for smaller businesses to pay for practical support for importing and exporting, such as dealing with new customs, rules of origin, and VAT rules. |

|

Put in place trade facilitation measures to smooth disruptions at the border. |

The introduction of further border checks on EU imports is being phased in gradually from 2023. |

The labour market is tight

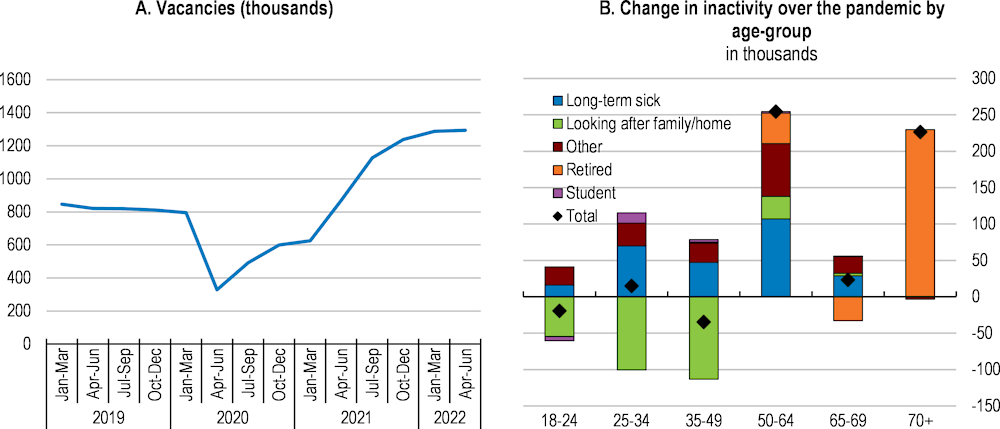

The labour market bounced back quickly from the pandemic shock, with the number of vacancies reaching a record high of almost 1.3 million in the first quarter of 2022 (Figure 1.8, Panel A). Government support through the job furlough scheme helped to keep the rise in unemployment contained during the pandemic (OECD, 2020[1]). After peaking at 5.2% in the fourth quarter of 2020, unemployment fell to a pre-pandemic low of 3.7% in the first quarter of 2022. The gradual phasing out of the furlough scheme ensured a smooth transition and did not lead to a pick-up in unemployment once the scheme ended in October 2021. The COVID-19 crisis disproportionally affected the 16 to 25 years olds, with the employment rate declining, and their economic inactivity and unemployment rates rising by more than those aged 25 and over (Office for National Statistics, 2021[6]). However, individuals aged under 25 were also quicker in finding a job once restrictions eased. By contrast, inactivity rates increased for people aged 55 and older as the pandemic continued, with many of them dropping out of the labour force and entering early retirement. The overall inactivity rate remains above pre-pandemic levels mainly due to people studying and due to long-term sickness (Figure 1.8, Panel B), a development that is not unique to the United Kingdom (Box 1.3).

Figure 1.8. The labour market has rebounded

Note: Panel A: Vacancies exclude agriculture, forestry and fishing. Latest data refers to Mar-May 2022. Panel B: Shows changes between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2021.

Source: ONS, labour market statistics.

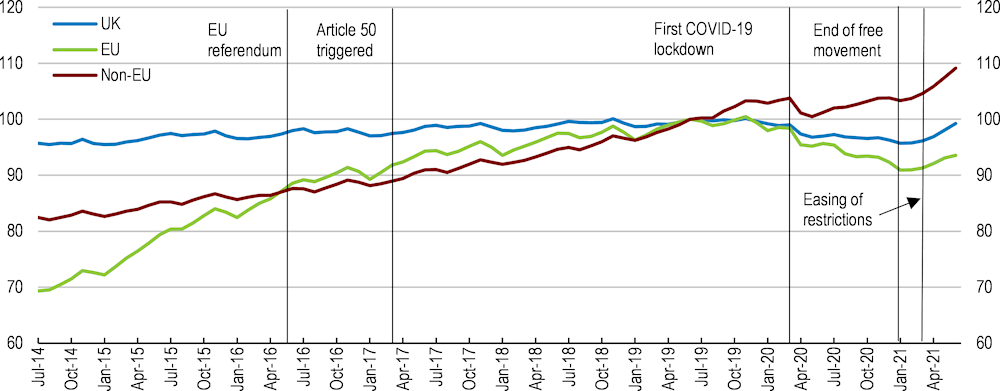

Labour shortages have been partially exacerbated by reduced net migration. Towards the end of 2021, labour shortages predominantly emerged in low-skilled sectors that were particularly affected by the pandemic and those in which a high share of EU-born migrants were working, such as the hospitality sector (13% of workers) and the transport and storage sector (11% of workers) (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[7]; Fernández-Reino and Rienzo, 2021[8]). Surveys suggest that half of all firms are having difficulty recruiting new workers, while around one in five firms are having issues retaining existing staff. Although most of the shortages can be explained by economic restructuring due to the pandemic, one in ten firms report that the UK’s point-based immigration regime is causing labour shortages (De Lyon and Dhingra, 2021[9]). From 2019 to 2020, immigration is estimated to have fallen between 50% and 60% (Office for National Statistics, 2021[10]), although these numbers should be taken cautiously because of difficulties in data collection during the pandemic and a change in methodology (Box 1.4). Immigration of EU-born nationals decreased slightly more than that of non-EU nationals (around 67% compared to 50%), a trend that is likely to have continued following the end of free movement of labour between the United Kingdom and the European Union since January 2021. In the context of a tight labour market, the government should ensure that the migration system is sufficiently flexible to quickly address rising labour shortages.

Box 1.3. Labour market participation in the US after the heights of the pandemic

In the US, the employment-to-working age population ratio fell by 10 percentage points between January and April 2020. While the employment fall was more gradual in the UK, reaching a maximum of 2 p.p. in the fourth quarter of 2020 relative to 2019Q4, both countries found themselves in similar situations regarding labour market tightness. Employment in the US gradually recovered, but the aggregate labour force participation rate remains below the pre-pandemic level and about 0.4 percentage points below where the Congressional Budget Office expected it to be in their pre-pandemic forecast. This mostly reflects the significant decline in the participation rate of older workers. In particular, there has been a fall in the share of existing retirees transitioning back into the labour force. In addition, a continued decline in immigration, from a combination of the pandemic along with pre-pandemic policies, has also weighed on labour supply and the participation rate. While concerns about contracting COVID-19 may have kept some from returning to work, especially those previously in face-to-face industries with heightened transmission risk, recent numbers suggest that it is unlikely that there will be a large increase in the number of older workers who have moved into retirement re-entering the labour force.

Source: OECD Economic Survey of the USA 2022, forthcoming.

Box 1.4. EU migration post-Brexit

Before Brexit, free movement rules gave EU citizens the right to live and work in the United Kingdom without requiring permission. As of 1 January 2021, EU citizens (except Irish citizens) who wish to move to the United Kingdom are subject to the same new Points Based Immigration System that also applies to non-EU citizens. The Point Based Immigration System is aimed at the most highly skilled workers, skilled workers, students and a range of other specialist work routes including those for global leaders in their field and innovators. For the skilled worker route, points are awarded for a job offer at the appropriate skill level, knowledge of English and being paid a minimum salary. People will normally need to be paid at least GBP 25 600 per year, have enough money to pay the application fee, the health care surcharge and be able to support themselves. The visa lasts for up to five years before it needs to be extended. Alongside the skilled worker route, several other new routes have opened over 2019 and 2020 including Global Talent, Innovator, Start-up, Graduate, Student and Child Student, Further routes are opened in 2022 for entrepreneurs and highly skilled people, including the Global Business Mobility route (April 2022), the High Potential Individual route (May 2022) and the Scale-Up route (August 2022).

Effect of new rules on EU migration

The end of free movement for EU citizens coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. It can be expected that both the pandemic and Brexit have fundamentally changed migration patterns in and out of the United Kingdom. The effect is still unclear due to data collection issues and changes in methodology. The usual source for measuring migration in the UK, the International Passenger Survey (IPS), was suspended at the start of the pandemic. Instead, the ONS developed experimental statistical models which indicate that EU net migration was negative in 2020, with an estimated 94 000 more EU nationals leaving the UK than arriving. EU immigration dropped considerably in 2020 compared with previous years, while numbers of EU people emigrating held steady (Office for National Statistics, 2021[10]). In addition, the ONS estimated the number of migrants in the United Kingdom using payroll information (Figure 1.9), which show a decline in pay-rolled employment held by EU nationals since the onset of the pandemic, and although there is a slight improvement from 2021 onwards, it is not as pronounced as for non-EU nationals.

Figure 1.9. The number of pay-rolled employment held by EU nationals has declined

Change in pay-rolled employments by nationality, June 2019 = 100 (non-seasonally adjusted)

Source: OECD (2021[11]); Office for National Statistics (2021[12]); Figure: Office for National Statistics (2022[13]).

Consumption has supported growth but confidence is deteriorating

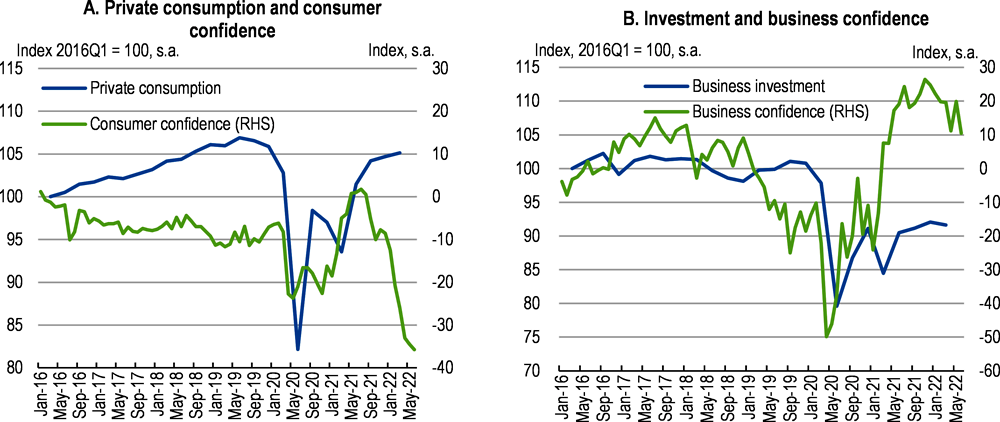

Private consumption fuelled the recovery as containment restrictions were eased (Figure 1.10, Panel A). However, consumption remains volatile, in particular as the cost of living is rising as reflected by developments in consumer confidence. While consumer confidence has plummeted amid rising goods and energy prices (see below), further aggravated by spill over effects from the Ukraine war, business confidence so far remains well above pre-pandemic levels. Business investment gradually improved following the COVID-19 crisis aided by tax incentives (Figure 1.10, Panel B), but remains subdued and below pre-pandemic level. To support business investment, the government announced a two-year tax “super-deduction” in the March 2021 budget. Companies investing in new assets between 1 April 2021 and 31 March 2023 can claim a 130% capital allowance on qualifying plant and machinery investments and a 50% first-year allowance for qualifying special rate assets.

Figure 1.10. Investment is recovering but confidence is volatile

Note: Panel B: Business confidence refers to the manufacturing sector. Business investment refers to private non-residential gross fixed capital formation.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and OECD (2022), OECD Main Economic Indicators (database).

Low income households are pressured by rising cost of living

Quickly rising cost of living have resulted in increasing pressure on people’s incomes. As a response, the government introduced several measures to aid households with rising energy costs in February and March 2022. In May 2022, the government introduced new measures totalling GBP 15 billion (about 0.7% of GDP), which provide temporary support to households with rising energy costs mainly targeted to those most in need. About 8 million households on means-tested tested benefits will receive a one-off payment of GBP 650 this year paid in two instalments, and one-off payments of GBP 300 will go to pensioner households and GBP 150 to individuals receiving disability benefits. The previously announced energy discount for 2022 is doubled to GBP 400 per household and becomes non-repayable. This targeted and temporary support is welcome as it helps to temporarily ease the financial distress of the most vulnerable households.

The May measures came on top of previously announced measures bringing total support in 2022 to a sizable GBP 37 billion (1.5% of GDP). Previous measures announced include, in March, a GBP 5p per litre cut in fuel duty, an increase in the national insurance threshold, zero-VAT on energy efficiency home improvements and an extra GBP 500 million for the household support fund managed by local councils, and in February a GBP 200 discount on energy bills and a targeted GBP 150 rebate on council tax. These measures are welcome. The May package in particular is better targeted at low-income households and those out of work.

Part of the May support package will be financed by higher borrowing, and GBP 5 billion will be funded by a new Energy Profits Levy. However, to ensure that investment continues to take place in UK oil and gas extraction, the government introduced within the Energy Profits Levy a new 80% investment allowance. While higher UK extraction reduces dependence of imports of fossil fuels, the government should also consider expanding the investment allowance to include renewables to aid the transition to net zero.

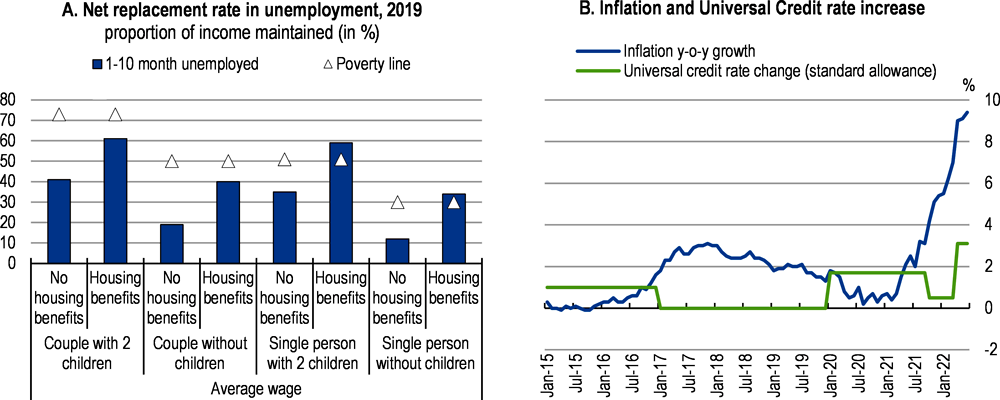

Apart from temporarily introduced measures, people with low income, who are out of work or who are unable to work can receive benefits of the Universal Credit, the main support to cover living costs. The Universal Credit integrates a number of the legacy system’s benefits and aims at simplifying access and extending the existing activation efforts across all benefits (OECD, 2020[1]). During the height of the COVID-19 crisis, the government swiftly adapted the claim process and temporarily lifted payments by GBP 20 per week. Although this timely government response successfully avoided an increase in income inequalities during the pandemic, non-working households were worse off in real terms as this temporary support was withdrawn in October 2021 (Brewer and Tasseva, 2021[14]; Bronka, Collado and Richiardi, 2020[15]; HM Treasury, 2020[16]; Waters et al., 2020[17]). Rising inflation since mid-2021 has contributed to a significant decline in real terms of Universal Credit. In the Autumn Budget 2021, the government announced to increase earnings for working universal credit recipients by raising work allowances by GBP 500 a year and reducing the taper rate from 63% to 55%, which reduces the impact of the withdrawal of the GBP 20 per week raise and increases work incentives. This is welcome. However, at the beginning of 2022, the basic level of Universal Credit in real terms had fallen 11.5% below its value when introduced in 2013.

At present, the targeted support to deal with cost of living is sizable and well targeted and will provide support to vulnerable households. However, in the longer term, the government should follow its annual uprating of universal credit as planned and ensure that it is adequate to cover the minimum living standard. Economic restructuring linked to the digital and green transition is likely to accelerate in coming years leading to rising unemployment among workers, especially low skilled workers, and such strengthened safety net could help address persistently high income inequality in the United Kingdom (OECD, 2018[18]). And, already before the pandemic, Universal Credit did not provide a sufficient safety net (Figure 1.11Figure 1.11, Panel A). The government froze Universal Credit benefit levels as part of the post-financial crisis fiscal consolidation between 2017 and 2020 (Figure 1.11Figure 1.11, Panel B). Moreover, unemployment benefits for many households remain below the levels of many other OECD countries and poverty rates are highest among households out of work (OECD, 2020[1]).

Figure 1.11. Unemployment benefits are low and uprating of Universal Credit has fallen behind inflation growth

Note: The indicator is the ratio of net household income during a selected month of the unemployment spell to the net household income before the job loss. Calculations refer to a jobseeker aged 40 with an uninterrupted employment record since age of 19 until the job loss. For a detailed description of the assumptions underlying the OECD Tax-Benefit model and the related policy indicators, please see the source.

Source: OECD (2022), Social protection and well-being database; UK Government, department for Work and Pensions; and ONS.

Economic growth will continue to slow

Growth is slowing amid persisting supply shortages and rising inflation. Output is projected to grow by 3.6% in 2022 before stagnating in 2023 due to depressed demand (Table 1.2). Inflation will continue to rise, peaking at just over 10% in the fourth quarter of 2022, driven by increasing global prices of tradable goods and services due to continuous supply bottlenecks and higher global energy prices. Continued tightness of the labour market is expected to feed through to higher wage growth in 2022 and 2023, but with wage growth remaining below inflation. Tighter monetary policy and easing supply constraints over 2023 are expected to help inflation decline to 4.7% by the end of 2023.

Private consumption is expected to slow as rising prices erode households’ income. However, spending will be supported by further declines in the households saving rate to below pre-pandemic levels, with some households taking on more debt to keep up with the rising cost of living. Unemployment is set to remain low but gradually increase to 4.5% by the end of 2023 due to weaker demand. Business investment will be supported by the super deduction for some types of investments available until April 2023, although the positive effect will be damped by rising interest rates, high energy prices and lingering uncertainties. Trade intensity with trading partners in Europe will decline, as growth in Europe is expected to slow amid the EU embargo on Russian oil. Public investment will be affected by supply shortages in 2022, hindering planned investment, but is expected to pick up in 2023 with planned spending increases on infrastructure and climate. The general government deficit is projected to decline gradually to 5.3% of GDP in 2022 and 4.1% of GDP in 2023.

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2019 prices)

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

|||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

2,174.4 |

1.7 |

-9.3 |

7.4 |

3.6 |

0.0 |

|

Private consumption |

1,412.3 |

1.3 |

-10.6 |

6.2 |

4.5 |

0.7 |

|

Government consumption |

399.0 |

4.2 |

-5.9 |

14.3 |

1.4 |

0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

386.5 |

0.5 |

-9.5 |

5.9 |

8.0 |

2.1 |

|

Housing |

112.0 |

-2.5 |

-12.2 |

13.8 |

7.7 |

0.0 |

|

Business |

217.3 |

0.9 |

-11.5 |

0.8 |

4.3 |

1.9 |

|

Government |

57.2 |

5.0 |

2.6 |

9.6 |

19.2 |

5.7 |

|

Final domestic demand |

2,197.8 |

1.7 |

-9.5 |

7.9 |

4.5 |

1.0 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

4.9 |

-0.1 |

-0.6 |

0.6 |

3.5 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

2,202.7 |

1.6 |

-10.2 |

8.3 |

8.0 |

0.9 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

663.3 |

3.4 |

-13.0 |

-1.3 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

691.6 |

2.9 |

-15.8 |

3.8 |

15.7 |

3.6 |

|

Net exports1 |

-28.3 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

-1.4 |

-4.2 |

-0.7 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|||||

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

1.8 |

1.5 |

-1.2 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

Output gap2 |

. . |

-0.6 |

-11.1 |

-3.3 |

-0.9 |

-2.0 |

|

Employment |

. . |

1.1 |

-0.8 |

-0.5 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

|

Unemployment rate |

. . |

3.8 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

2.0 |

5.1 |

0.3 |

5.7 |

4.9 |

|

Consumer price index (harmonised) |

. . |

1.8 |

0.9 |

2.6 |

8.8 |

7.4 |

|

Core consumer prices (harmonised) |

. . |

1.7 |

1.4 |

2.4 |

6.4 |

5.9 |

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

. . |

-1.6 |

8.2 |

4.4 |

-1.5 |

-5.3 |

|

Current account balance4 |

. . |

-2.7 |

-2.5 |

-2.6 |

-7.2 |

-7.6 |

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

. . |

-2.3 |

-12.8 |

-8.3 |

-5.3 |

-4.1 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-2.0 |

-5.1 |

-6.2 |

-4.8 |

-3.0 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

. . |

-0.1 |

-3.6 |

-3.9 |

-2.0 |

-0.2 |

|

General government gross debt4 |

|

118.5 |

149.1 |

143.1 |

139.2 |

138.6 |

|

General government net debt4 |

. . |

84.7 |

109.3 |

105.0 |

101.1 |

100.5 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

1.4 |

2.4 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

0.9 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

2.5 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 111 database.

Risks to the outlook are considerable. Spill-overs from economic sanctions, higher than expected energy prices as the Ukraine war drags on, and a deterioration in the public health situation due to new COVID strains are significant downside risks (Table 1.3). The United Kingdom has limited direct trade and financial linkages with Russia and Ukraine, but higher global energy prices and further economic slowdowns in major European trading partners could add to higher than expected goods and energy prices weighing on consumption and further lower growth. A prolonged period of acute supply and labour shortages could force firms into a more permanent reduction in their operating capacity. Progress in trade deals could support trade and improve the medium- to long-term outlook.

Table 1.3. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Uncertainty |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

Pandemic outbreaks |

Reduction of activities where distancing is a concern could lead to firm failures and increased unemployment. Highly contagious forms of the virus could affect the provision of labour due to isolation and quarantine requirements. |

|

Intensified and prolonged geopolitical conflicts in Europe |

Spill-overs from Russia’s invasion could drive up energy prices, as the Ukraine war drags on, squeezing household incomes and slowing down economic growth on the back of lower consumption. |

Monetary policy should continue to tighten to curb the risk of a de-anchoring of inflation expectations

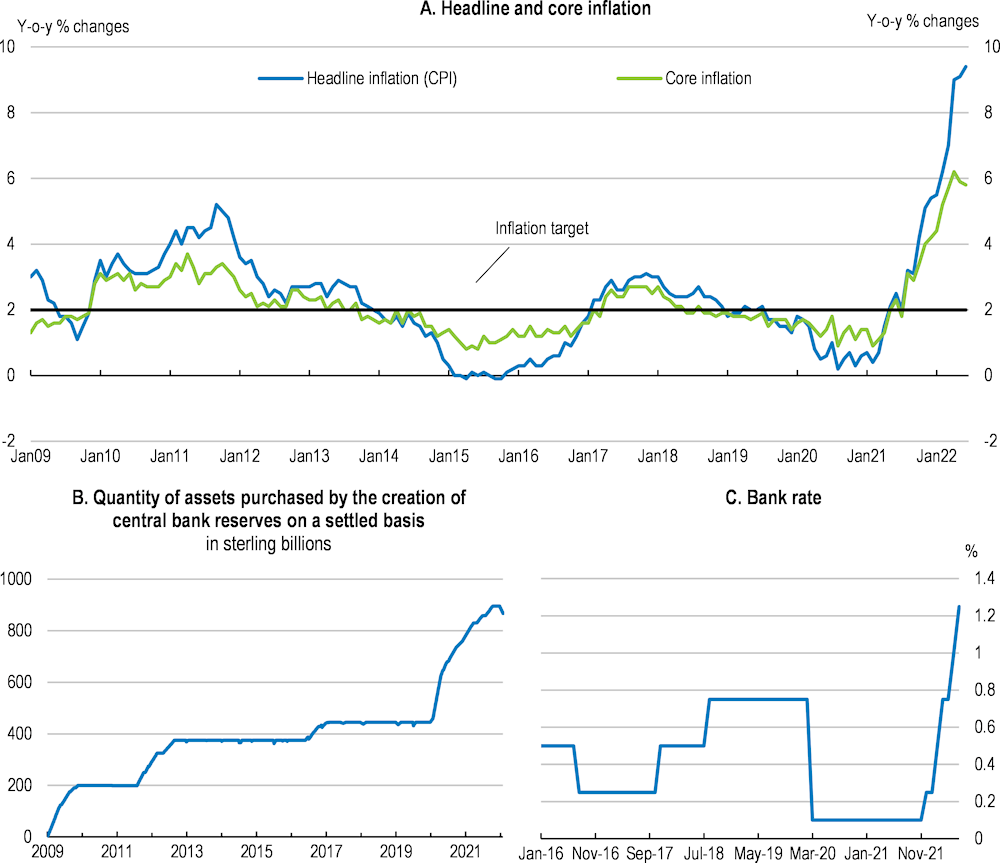

Inflationary pressures started to mount in the second half of 2021 on the back of supply and labour shortages and rising energy prices. CPI inflation rose from 2% in summer 2021 to 9.4% in June 2022 (Figure 1.12, Panel A). The surge reflects elevated energy and goods prices, largely determined by global markets, global supply shortages and strong (pent-up) demand for goods exacerbated by higher energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Administrative trade costs have increased due to Brexit. Core inflation has significantly picked up as well (Figure 1.12, Panel A) and inflation expectations have increased. Tight labour markets, with high turnover and record vacancies have led to solid wage growth since 2021, reaching 4.8% year-on-year in January 2022 and surveys point at continued strong pay growth in 2022; the government also implemented a 6.6% increase in the minimum wage in April 2022.

Monetary policy, highly accommodative during the pandemic, started tightening from end-2021. In March 2020, the Bank of England (BoE) cut the bank rate from 0.75% to 0.1% and increased its bond purchasing programme over the course of the crisis to a total of GBP 895 billion (about 44% of GDP in 2020) (Figure 1.12, Panel B). Since December 2021, the BoE gradually has increased the policy rate from 0.1% to 1.25% in June, on the back of the recovery and rising inflation pressures (Figure 1.12Figure 1.12, Panel C). The BoE ended its quantitative easing program in December 2021. In February 2022, the BoE decided not to reinvest any future maturities and announced to gradually sell its stocks of sterling corporate bonds and end the program towards the end of 2023. A strategy for selling the stock of government bonds will be discussed at the August 2022 monetary policy meeting.

In the context of high inflation and rising wages, further tightening of monetary policy is welcome to support the return of inflation to target and to anchor inflation expectations, which remain elevated at around 6% for the next 12 month as measured by the YouGov/Citigroup survey in June 2022. Clear and carefully communicated forward guidance will be important to limit second-round effects and avoid uncertainty. The decline in asset holdings should continue to follow a predictable and well-communicated strategy to guide markets and reduce financial stability risks. As planned, the Bank should outline a clear quantitative tightening strategy to manage market expectations.

Figure 1.12. Monetary policy, supportive during the crisis, has started to tighten

The financial system withstood the shock from the COVID-19 crisis and the withdrawal from the EU Single Market

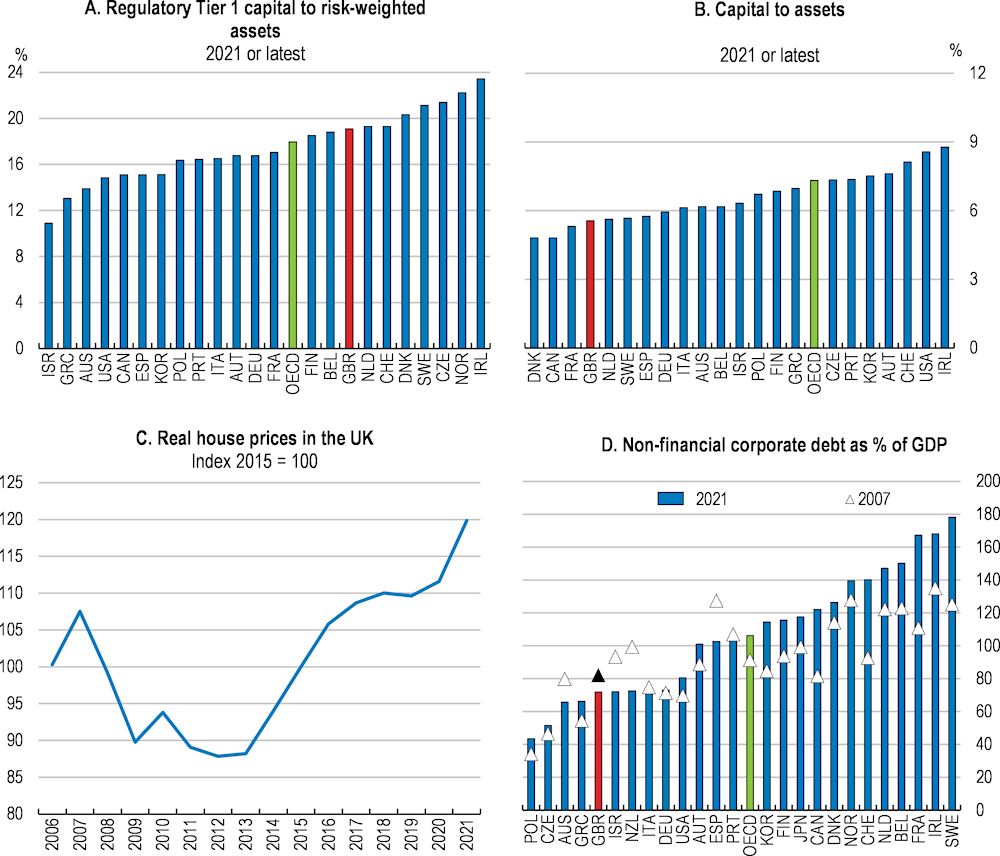

The banking sector entered the pandemic well capitalised, allowing it to absorb the effects of the pandemic and continue to provide services to households and businesses. While banks are still highly leveraged in gross terms, average risk-weighted capital is around the OECD average (Figure 1.13, Panels A and B). To prevent financial tightening that could exacerbate the crisis, the Bank of England lowered the countercyclical capital buffer during the pandemic. Multiple government support schemes also softened the pandemic’s impact and contained insolvencies. Government loan schemes supported SMEs who bore the brunt of COVID-19. Income support through the furlough scheme and payment deferrals supported households. The share of non-performing loans increased somewhat at the start of the pandemic, but remained relatively low and is gradually declining (Bank of England, 2021[19]).

Figure 1.13. The banking system is well capitalised

Source: IMF (2021), IMF Financial Soundness Indicators Database; OECD (2021) National accounts at a glance; and BIS.

The economic consequences of the pandemic will take time to resolve and some of the impact is only now becoming visible as support measures are withdrawn. A recent stress test by the Bank of England (2020[20]) suggests that the financial sector could withstand a very severe downturn in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic shock of 2020.

Risks arising from rapidly rising house prices remain contained, but vigilance remains warranted. House prices increased by 11.8% over the year to September 2021 fuelled by increased demand as a result of the pandemic, supply pressures and tax incentives (Figure 1.13, Panel C). But compared to before the pandemic, high loan-to-value mortgages remain a smaller share of new mortgages (Bank of England, 2021[21]). Most households that benefited from mortgage payment deferrals at the start of the pandemic have restarted full or partial repayments (Bank of England, 2021[22]). In June 2022, the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee announced the removal of the affordability test, which assesses whether the borrower could afford payments if the policy rate increases by three percentage points above their reversion rate specified in the mortgage contract. Removing this test simplifies the framework and reduces constraints for some borrowers. The Loan to Income (LTI) flow limit, which is seen as more effective, remains in place in addition to the affordability measures of the Financial Conduct Authority (Bank of England, 2021[19]). Because the FCA affordability test is less stringent on average over interest rate cycles, it is important that the effect of simplification is monitored to ensure macroprudential tools contain risks from the mortgage market for the UK banking system and remain effective.

Corporate debt has increased during the pandemic, including borrowing from government support packages, but corporate debt levels remained well below the OECD average as a percentage of GDP in 2020 (Figure 1.13, Panel D). Simulations show that it would take a large shock to impair business ability to service their debt on aggregate (Bank of England, 2021[19]). However, some pockets of risk exist due to the uneven distribution of debt (Bank of England, 2021). For instance, debt held by SMEs has increased. Risks to lenders are limited as the majority of lending through the pandemic occurred with government guarantees, at low and fixed interest rates (Bank of England, 2021[19]). Insolvencies have been rising to pre-pandemic levels (see above), but already before the pandemic, UK’s insolvency regime was fairly efficient and greater flexibility was provided through the 2020 Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act. The insolvency regime should therefore be able to deal with a rise in cases (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018[23]; OECD, 2020[1]). In addition, UK banks hold around GBP 31 billion in provisions to deal with future credit losses (Bank of England, 2021[19]).

As the immediate effects of the pandemic fade, macrofinancial vulnerabilities may emerge as the consequences of leaving the European Union and the transition to net zero come to the forefront. With the departure from the European Union, some segments of the financial sector based in the United Kingdom can no longer directly service EU clients through the EU passporting regime as they could previously. Access to EU labour has become more cumbersome due to new visa regulations. However, the transition so far has occurred smoothly (see Box 1.5). The long-term impact of leaving the EU Single Market on the UK financial sector remains uncertain. The government is using its new powers to replace the EU financial services framework and will introduce a financial services and markets bill this year. This will include updating the objectives of the financial regulators and revising capital markets regulation. The government is consulting to better understand how reforms to insurance regulation (Solvency II) would enable insurance firms to invest more in long-term infrastructure products and hold less capital (Glen, 2022[24]). Although some adjustments to insurance regulation are warranted - the European Union is going through a similar process - and incentivising private sector investment in longer term and more illiquid assets is positive, the development of new regulation should be approached carefully and financial stability implications, and costs to policyholders, should continue to feature prominently.

Adjusting to the pandemic, Brexit and net zero will require some reallocation of labour and capital. UK SMEs are largely dependent on bank funding, but larger firms rely heavily on market funding. The resilience of the banking system and a return to risk appetite mean lending conditions to firms remain supportive while large firms maintained access to market-based funding (Bank of England, 2021[19]).

Transitioning to net zero provides investment opportunities, but may also put additional pressures on financial institutions, particularly in the transition phase. Climate change increases the scale and frequency of natural disasters such as floods and storms, raising the claims burden for insurers and re-insurers, even though this will be reflected in premiums over time. In 2021, the Bank has launched the Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) exercise to assess the resilience of major UK banks, insurers, and the wider financial system to different climate scenarios, which is a timely innovation.

Box 1.5. The effect of leaving the European Union on the financial services sector

In financial services, an important source of the UK’s comparative advantage, market access between the UK and the EU is to a significant extent managed through equivalence, where either side can grant the other equivalent status in relation to a number of legislated areas. In November 2020, the UK published a guidance document setting out its approach to operating its equivalence framework and granted a package of equivalence decisions in respect of the EEA states. The UK has replicated most of the equivalence determinations in respect of overseas jurisdictions made by the European Commission pre-Brexit. As of November 2021, 32 jurisdictions plus the EEA benefit from UK equivalence decisions The European Union granted equivalence for UK regulatory standards only temporarily and in specific areas, such as derivatives clearing.

Following its departure from the European Union, the United Kingdom needs to establish an independent regulatory framework. At the point of EU exit, directly applicable EU legislation (including that relating to financial services) was brought into the UK law so that it would continue to have effect in the UK after withdrawal. This “retained EU law” was amended as necessary to ensure that it would continue to operate effectively in the UK after exit (a process known as “onshoring”). This provided continuity and stability at the point of exit, but it was not intended to be a permanent approach to financial services regulation. This retained EU law will now be repealed so that regulation in these areas can be brought into line with the UK’s domestic model of regulation where the design and implementation of firm-facing rules is the responsibility of the UK regulators (Bank of England (BoE), Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)). The goal of the UK government is to create a financial services sector, built around four themes of Openness; Green Finance; Technology; and Competitiveness. The government intends to tailor its approach to financial services regulation to reflect the UK’s new position outside the EU, while ensuring it supports and promotes the interests of UK markets and maintains high regulatory standards in the face of new and evolving risks. As announced in the Queen’s Speech on 11 May 2022, the government will be bringing forward a Financial Services and Markets Bill, which will deliver on these commitments by implementing the outcomes of the Future Regulatory Framework (FRF) Review as well as a series of important initiatives underpinning the government’s vision.

The transition to the new regime on January 1, 2021, went smoothly thanks to joint efforts by financial firms and UK authorities. There are no formal statistics on the number of UK-based financial services jobs that have moved from the United Kingdom to the European Union, but estimates suggest around 7 000 jobs have been relocated by March 2022 (EY, 2022[25]), which remains well below most estimates before EU exit. The long-term impact of EU exit on the UK financial sector remains unclear.

Some aspects of EU exit were phased in gradually, including:

A Temporary Transition Power (TTP) given by HMT to the FCA, PRA and BoE allowed them to temporarily waive or amend rules post-Brexit until end-March 2022 or December 2022. In the areas where TTP relief ended in March 2022, there has been no material disruption as a consequence.

The Temporary Permissions Regime (TPR) allows temporary continued access to the UK market for EEA-based firms that were passporting into the United Kingdom at the end of the transition period (31 December 2020). During the temporary period of access, the firms must seek full authorisation by the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) or the FCA as required in the UK to continue to access the UK market (FCA, 2018). This will happen in a staggered process. Around 1500 EEA-based firms entered the FCA Temporary Permissions Regime at the beginning of 2021. The Temporary Permissions Regimes will expire at the end-2023.

Derivative Clearing: The European Union has granted the United Kingdom temporary equivalence status with regard to clearing, allowing EU derivatives to be cleared in the United Kingdom. This permission expires in 2025.

Source: FCA (2021), “Seizing opportunity – challenges and priorities for the FCA”. https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/seizing-opportunity-challenges-priorities-fca; FCA (2020), “Onshoring and the Temporary Transitional Power”, https://www.fca.org.uk/brexit/onshoring-temporary-transitional-power-ttp; FCA (2018), “Temporary permissions regime“, https://www.fca.org.uk/brexit/temporary-permissions-regime-tpr.

Fiscal policy has to balance consolidation with supporting growth and addressing investment needs

Tax increases will contribute to a declining fiscal deficit

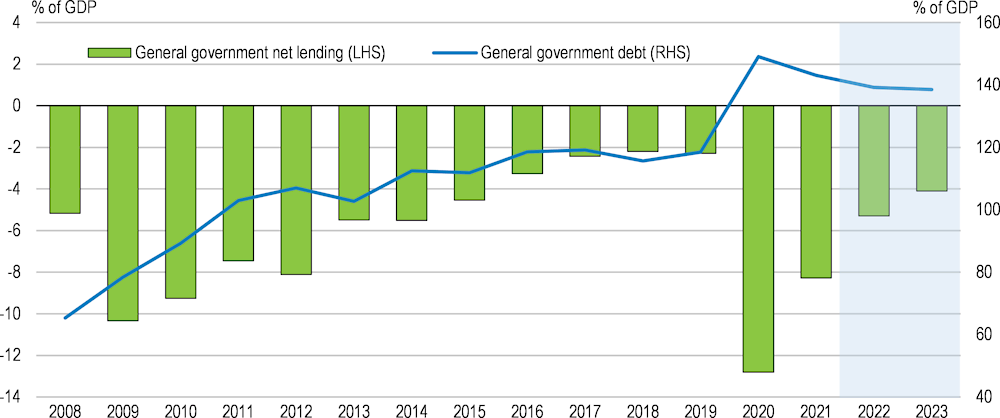

The pandemic triggered a strong fiscal response of around 19% of 2020 GDP by September 2021 supporting household incomes and attenuating the rise in unemployment and business insolvencies (IMF, 2021[26]). The budget deficit rose to a record -12.8% in 2020 and gross public debt increased by 36 percentage points (Figure 1.14). As the main support measures were phased out in October 2021, the fiscal balance improved and gross public debt declined to 143.1% of GDP in 2021.

Figure 1.14. The pandemic led to a record high budget deficit that pushed up public debt

The government has committed to a gradual medium-term fiscal consolidation plan and to increased tax revenues. National-insurance contributions rose by 1.25% from April 2022 to fund health and social care spending while tax free allowances and higher rate thresholds for income tax are frozen until 2025-26, a policy that now has a bigger positive impact on revenues than anticipated when introduced in early 2021 due to high inflation. The corporate income tax rate will increase from 19% to 25% in April 2023. These tax changes will result in an increased overall tax intake from 33% of GDP in 2019-20 to almost 37% of GDP in 2026-27 as forecasted by the OBR, despite a hike in the national insurance threshold and a cut to income tax in 2024 (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2022[27]; Office for Budget Responsibility, 2022[28]). Overall, tax changes will put a higher share of the burden on richer households and will be progressive (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2022[27]), but still imply a higher individual tax liability for almost all workers in the coming years. Based on government medium term plans, the deficit will fall from about 15% in 2020-21 to around 1% of GDP in fiscal year 2024-25, with the largest fiscal withdrawal happening in 2023-24. Public net debt will fall from 96.5% of GDP in 2021 to 88% of GDP by 2025-26.

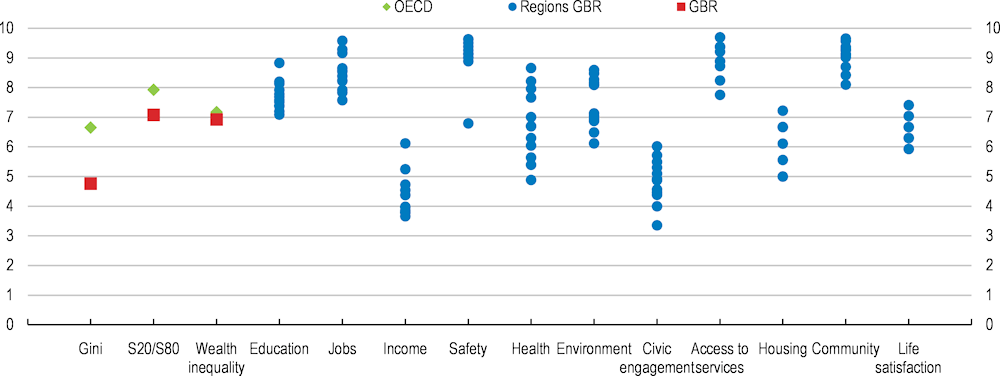

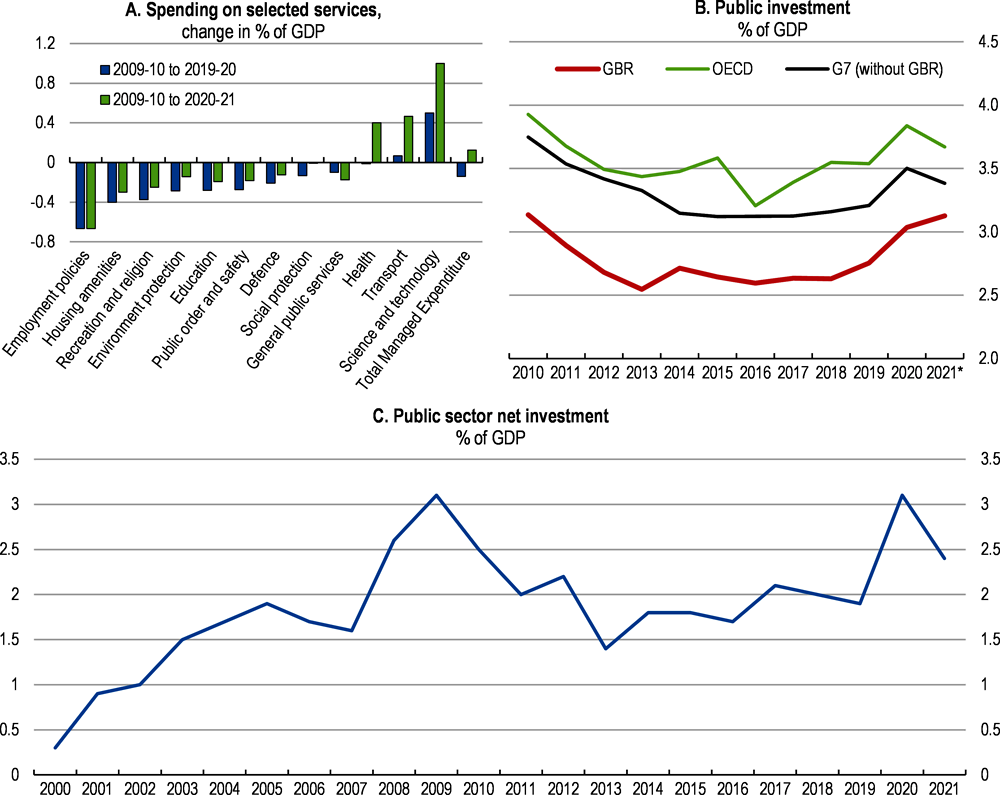

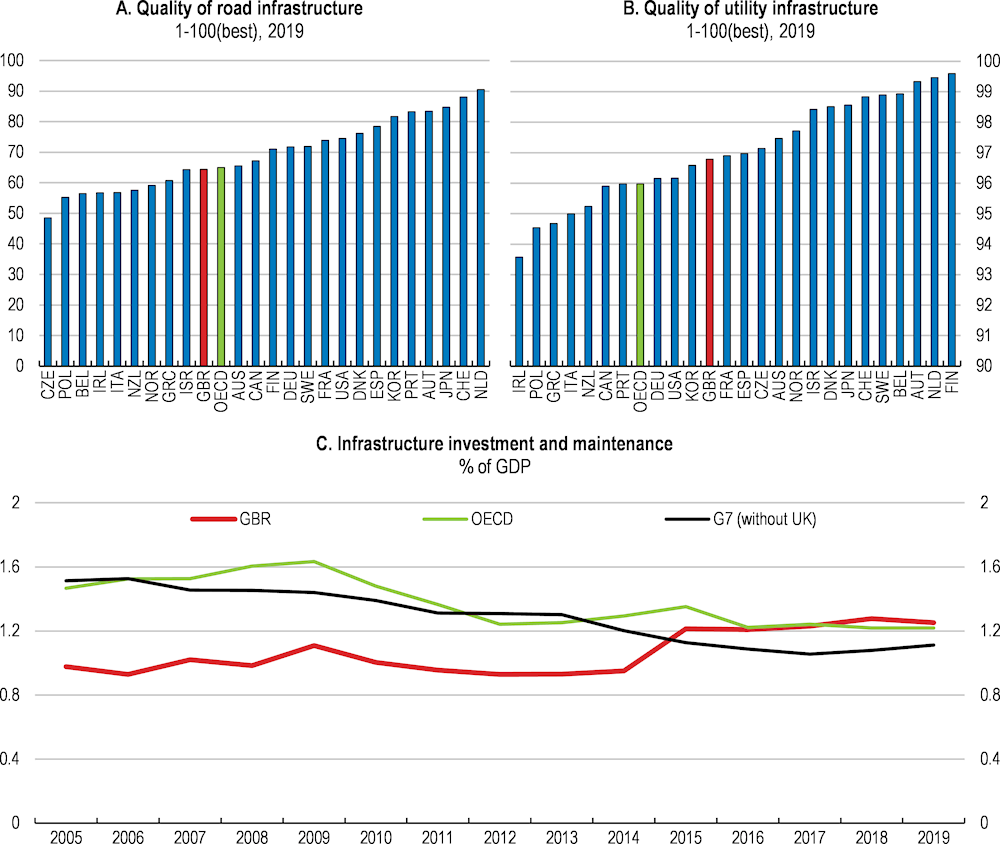

Fiscal consolidation will need to accommodate significant investment and spending needs

Fiscal policy will need to balance consolidation with public investment and spending needs. Planned higher spending and investment over the coming years is welcome after a decade of fiscal restraint and low public investment. But current plans still leave some areas (including employment policy and education) with more limited funding than before the global financial crisis (Figure 1.15, Panel A) and substantial investment is needed to address the green transition and levelling up agenda to reduce regional inequality. In 2020 and 2021, the government announced departmental spending increases of over 2% of GDP (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[7]). By 2024-25, public spending will be 41.6% of GDP - a historic high - of which 8.4% is allocated to health, 5.4% to pensions, 5% to education and 4.8% to welfare (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[7]). Rising inflation and interest rates will lead to a spike in debt interest rate payments in 2022-23 before declining as inflation is forecasted to gradually fall (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2022[28]). The health and social care levy is expected to raise around GBP 18 billion by 2026-27 (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[7]). This should be sufficient to cover short-term health funding needs, although other constraints such as staffing shortages might remain and indicators point at intense pressures on the NHS. More funding might be required for social care and to deal with long-term health cost pressures (Paul Johnson et al., 2021[29]). In line with the 2017 Industrial Strategy and the 2021 Plan for Growth (Box 1.7), public sector net investment is projected to be 2.5% of GDP on average per year up to 2026-27 (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2022[28]; 2021[7]). This is above levels observed in the United Kingdom in the previous decades but remains below the OECD average (Figure 1.15, Panels B and C).

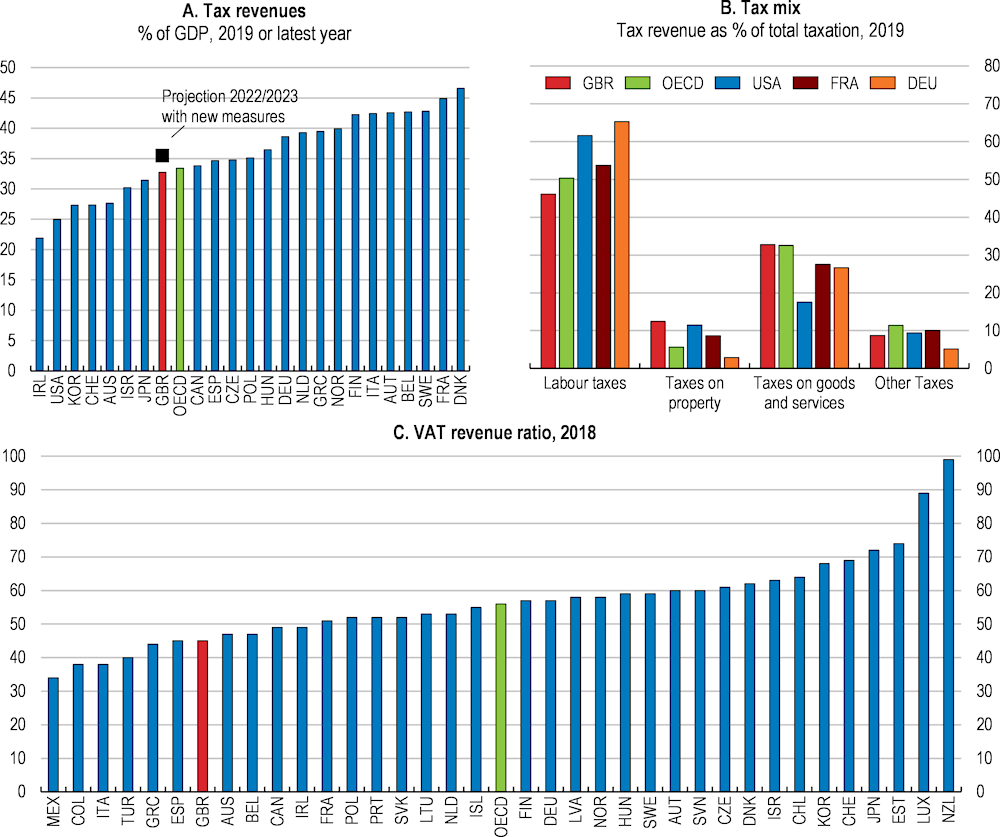

Spending and investment needs will remain high over the coming years, limiting the scope for tax cuts and requiring a focus on making the tax system more efficient and fairer. Tax revenues at 33% of GDP are lower than in peer European countries (Figure 1.16, Panel A), but are projected to reach about 37% of GDP the coming years (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2022[28]). A tax review into reliefs and allowances has been announced in the Spring Statement 2022 and is planned to go ahead before 2024 (HM Treasury, 2022[30]), which is welcome. It will be particularly important to review the existing tax and spending mix with a focus on ending reliefs and exemptions that do not serve an economic, social or environmental purpose. Tax breaks that tend to benefit higher-income households can be gradually reduced to improve the effectiveness of the tax system and its redistributive effects. The VAT base is eroded by various (partial) exemptions that exist for a wide range of goods including some financial service activities, some vehicles or gambling and that contribute to significant VAT revenue shortfalls (Figure 1.16, Panel C). Broadening the VAT tax base while compensating poorer households, would reduce distortions and make the tax system more efficient and effective, as discussed in previous Economic Surveys (OECD, 2020[1]; 2017[31]). Council tax could be made fairer and less distortive by adjusting thresholds for higher property values or even a proportional rate and by updating outdated property values that determine the amount due, as recommended in previous Surveys (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2015[32]; Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020[33]). To improve efficiency, the government should also consider reducing further the gap between national insurance rates for the self-employed and employed, which has increased in 2021 (Johnson, 2021[34]), as recommended in the last Economic Survey.

Figure 1.15. Public investment and spending on services is improving

Note: Panel A: Enterprise and economic development and Agriculture, fisheries and forestry are excluded. Panel B: Public investment refers to gross investment to allow for international comparability; as 2021 data was not yet available for all OECD countries, for the OECD estimate of 2021, data available for 2021 or latest were used. Panel C: Excludes public sector banks.

Source: ONS; and OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database).

The government proposed new fiscal rules in the October 2021 Budget. A new core target is set as a declining net sector debt ratio (excluding the Bank of England balance sheet), by the third year of the rolling forecast period. Three supplementary targets aim at balancing the budget (excluding public investment) by the third year, ensuring public sector investment remains below 3% of GDP on average across the 5-year rolling forecast period and welfare spending remains below a cap set by the UK Treasury. The framework allows a suspension of the targets in case of a significant negative shock. The independent fiscal advisory council, the Office for Budget Responsibility, forecasts that the fiscal targets will be reached, including a declining net sector debt ratio. Hence, the framework provides guidance about the medium-term plan for returning to debt sustainability. Fiscal rules were introduced in the late 1990s and were revised in 2010. Since 2010, they have been revised three times amid large economic shocks. It should be ensured that changes to fiscal targets are both credible and relevant. Sweden for example reviews its fiscal target regularly under a disciplined process, thus revisions to the target are carried out in a predictable and credible way. The government has announced that its fiscal rules will guide its policy for at least this Parliament and will be reviewed at the start of each subsequent Parliament to support credibility and confidence in the UK’s long-term fiscal trajectory.

Figure 1.16. Tax revenues are lower than in peer countries

Note: Tax revenues for GBR in 2022/2023 are projections from the last Economic Outlook report of the OBR.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Tax Revenue Statistics (database); and OBR Economic and fiscal outlook - October 2021.

Ageing related expenses will put pressure on public finances

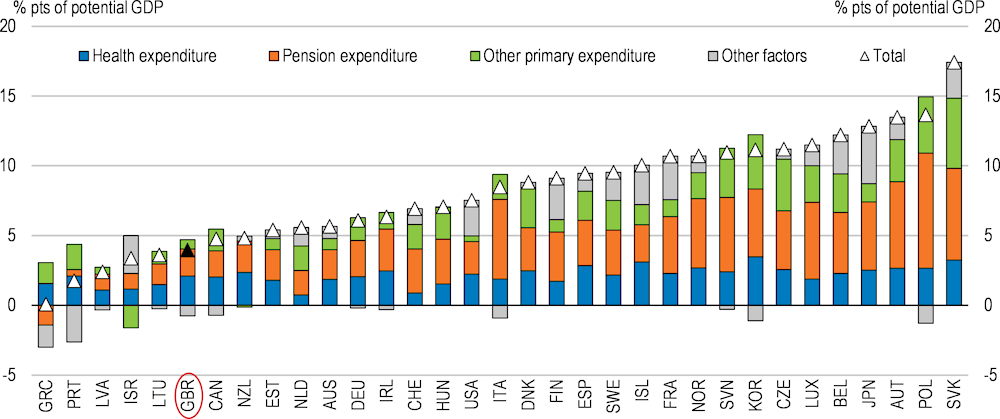

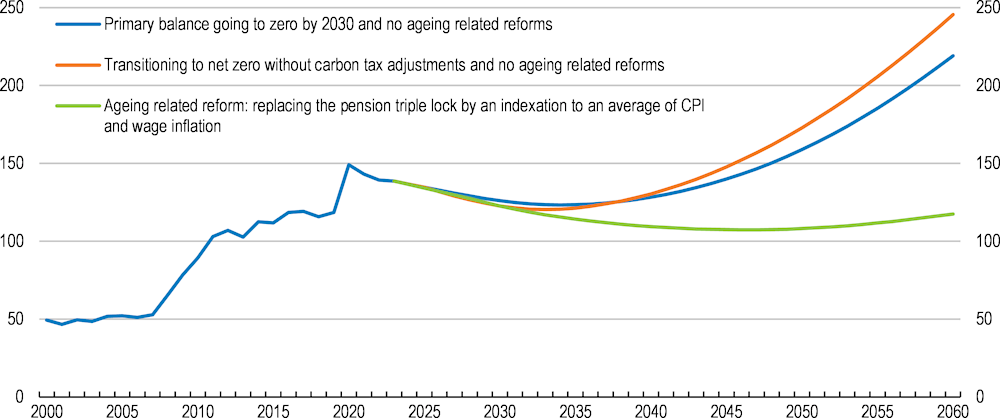

In the coming decades, the United Kingdom faces significant fiscal pressures mostly driven by ageing related increases in health, long-term care and pension expenditures. In a cross-country comparison these pressures appear mild as the structural primary revenue, or corresponding savings, would have to increase close to 5 percentage points of GDP to keep the current debt-to-GDP ratio constant (Figure 1.17). However, this does not take into account the effects of the green transition, which will require investment and lead to reduced revenue in the case of unchanged policy (Chapter 2). Under a baseline scenario of fiscal consolidation of about 1.5 percentage points of GDP over the next 10 years and no further reforms, ageing related costs would push up the public debt-to-GDP ratio close to 250% by 2060 (Figure 1.18Figure 1.18, blue line). Transitioning to net zero will create some shortfalls in revenues, most importantly in fuel excise duty, which provides annual revenues of about 1.6% of GDP. Shifting to electric vehicles and phasing out all new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030 according to government plans will result in a gradual loss and increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio beyond 250% by 2060 (Figure 1.18Figure 1.18, orange line). As discussed in Chapter 2, the fuel excise duty targets a number of externalities from road use and is an important revenue source. It should therefore be replaced by a new system to tax road use. Greenhouse gas related revenues from an expanded UK ETS or carbon tax can help finance necessary green investments, offset negative distributional effects of carbon pricing and help secure public acceptance (Box 1.6).

In the absence of improved productivity to sustain economic growth, long-term fiscal sustainability will depend on prudent policies and the implementation of reforms. Spending on state pensions and pensioner benefits is expected to increase from 6% of GDP in 2021-22 to 8.2% in 2067-68 (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2021[35]). To contain the rise, the retirement age is set to gradually increase to 67 years by 2028 and has to be reviewed regularly as per the Pension Act 2014. Under triple lock rules state pensions are increased by the highest of inflation, average earnings growth or a flat 2.5% rise, which is expensive. The triple lock is suspended for one year over 2022-2023 and should be eliminated, as recommended in the previous Survey (OECD, 2020[1]). Replacing the lock with the indexation of pensions to an average of CPI and wage inflation would help to contain public debt substantially (Figure 1.18Figure 1.18, green line; Box 1.6). Already replacing the triple lock with a more flexible system that allows deviations in case of unusual high earnings or inflation would give the government more control over long-term pension liabilities. In the United Kingdom, voluntary private occupational pension plans contribute more to gross pension replacement rates than state pensions (OECD, 2021[36]). The replacement rate for state pensions is lower than in many OECD countries putting pensioners without access to a private pension at risk of poverty. The reform of the triple lock should therefore be complemented by targeted direct transfers to limit the impact on poorer pensioners and limit poverty risks.

Figure 1.17. Ageing and health related expenditures add to future fiscal pressure

Change in structural primary revenue to GDP between 2021 and 2060 needed to stabilise the gross debt-to-GDP ratio, % pts of potential GDP

Note: The chart shows how the ratio of structural primary revenue to GDP must evolve between 2021 and 2060 to keep the gross debt-to-GDP ratio stable near its current value over the projection period (which also implies a stable net debt-to-GDP ratio given the assumption that government financial assets remain stable as a share of GDP). The necessary change in structural primary revenue is decomposed into specific spending categories and ‘other factors’. This latter component captures anything that affects debt dynamics other than the explicit expenditure components (it mostly reflects the correction of any disequilibrium between the initial structural primary balance and the one that would stabilise the debt ratio).

Source: Simulations using the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Figure 1.18. Reforms are needed to stabilise public debt

Gross government debt, % of GDP

Note: The baseline scenario assumes a fiscal consolidation allowing to reach a zero primary balance (which for simplification of the model includes interest receipts) by 2030 followed by a deterioration because of ageing costs. The baseline scenario assumes that the trip-lock pension is maintained. The pension reform scenario shows the impact of moving from trip-lock pension to CPI indexation. The fuel levy scenario shows the impact of early action on fuel levy in line with the OBR fiscal risk report which assumes a significant decline in the fuel levy from 2030 as new petrol and diesel cars will be banned from sales. Further general assumptions of the model are outlined in Guillemette (2021).

Source: OBR Fiscal risks report July 2021; and simulations based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Table 1.4. Past recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations from past Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Replace the pensions “triple lock” by indexing pensions to average earnings and ensure adequate income is provided to poorer pensioners. |

For the 2022-2023 financial year the earnings element of the triple lock was temporarily suspended given extremely high 2021 earnings |

|

Set a stable medium-term framework to improve guidance to policy and markets |

In 2021, the government has introduced a new fiscal framework including a core target of a declining net sector debt ratio, excluding the Bank of England balance sheet, by the third year of the rolling forecast and three supplementary targets. |

|

Align social security contributions between self-employed and employed, by increasing contributions paid by the self-employed. |

Reform to off-payroll working rules (IR35), designed to ensure individuals working like employees but through an intermediary, usually a personal service company (PSC), pay broadly the same Income Tax and National Insurance contributions (NICs) as those who are directly employed, were introduced for the private and voluntary sectors in April 2021 (public sector already in 2017). |

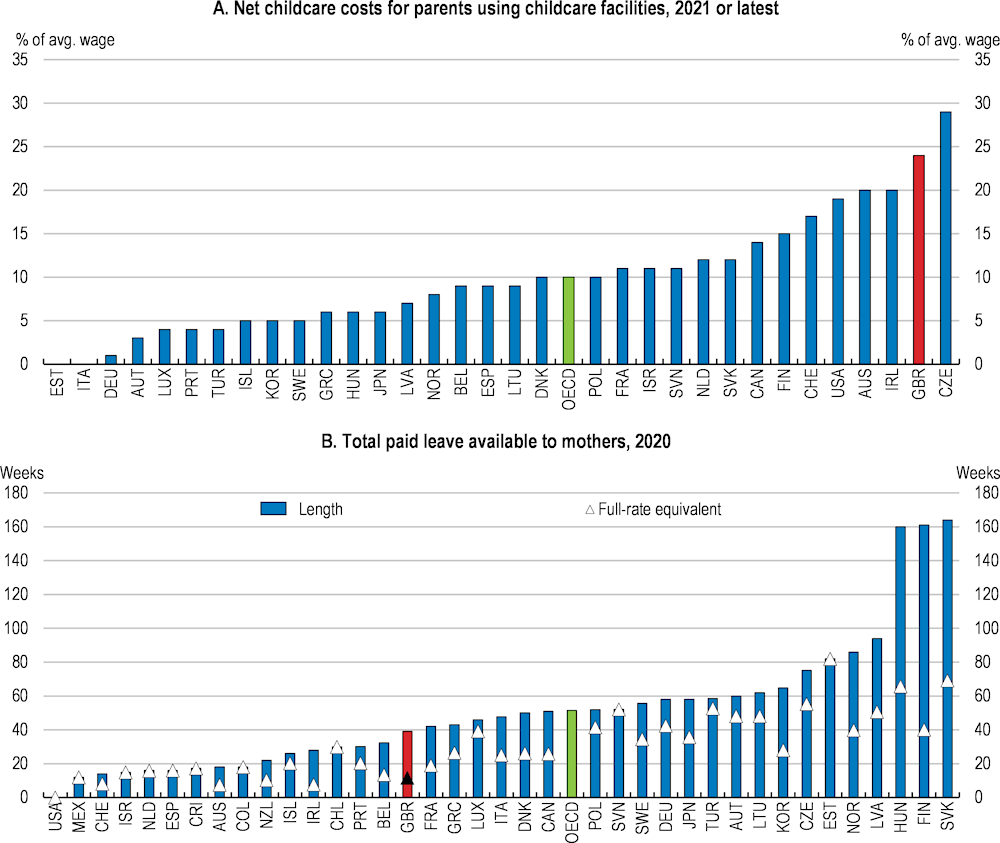

Box 1.6. Quantifying the impact of selected recommendations

This box summarises potential long-term impacts of selected structural reforms included in this Survey on GDP (Table 1.5) and the fiscal balance (Table 1.6). The quantified impacts are merely illustrative. The estimated fiscal effects include only the direct impact and exclude behavioural responses that may occur due to policy change.

Table 1.5. Illustrative GDP impact of selected recommendations

|

Policy |

Scenario |

Impact |

|---|---|---|

|

Policies to reduce income inequality |

Increased labour efficiency through 10% reduction of income inequality |

+0.3% of potential GDP on average over next 10 years |

|

Reduce the cost of childcare for parents |

Increase family benefits in kind by 10% |

+0.5% of GDP per capita after 10 years |

Source: OECD calculations using the OECD Economics Department’s long-term model; OECD calculations based on the framework in Égert and Gal (2017), “The Quantification of Structural Reforms in OECD Countries: A New Framework”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1354.

Table 1.6. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Measure |

Description |

Net fiscal impact; percentage of GDP |

|---|---|---|

|

Reduce the cost of childcare for parents |

Increase family benefits in kind by 10% |

-0.2% on average over next 10 years |

|

Increase the cap on paternity pay and relate it to father’s income |

↓ |

|

|

Shifting to an average of CPI and wage indexation of pensions |

1.9% on average over next 10 years |

|

|

Broadening VAT tax base |

Broadening the VAT tax base to the level of the OECD average keeping the standard rate |

1.5% |

|

Increase property taxes through the council tax |

Doubling the rates for bands E, F, G, and H, and E (last survey) |

0.4% |

|

Expanding the emissions trading scheme and/or implementing well-designed carbon taxes. |

↑ |

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Economics Department’s long-term model.

Raising productivity

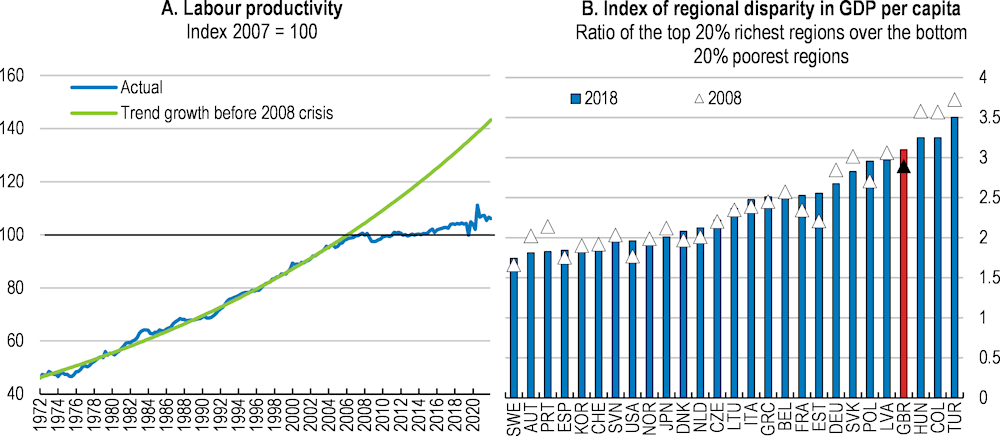

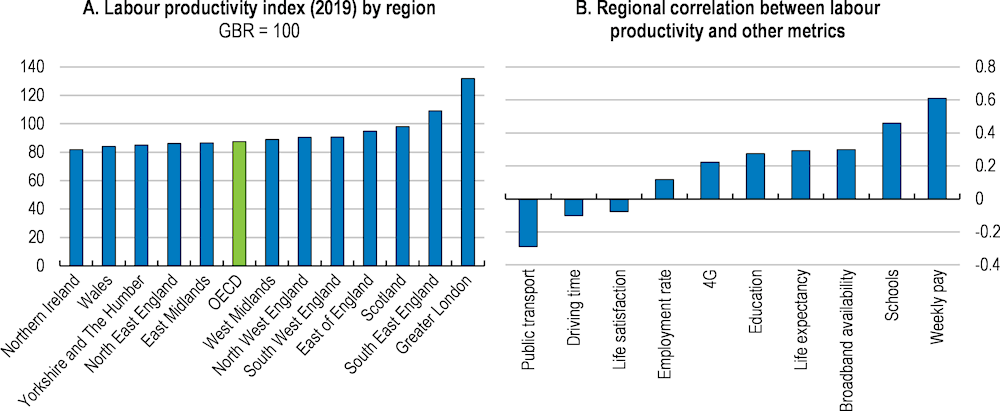

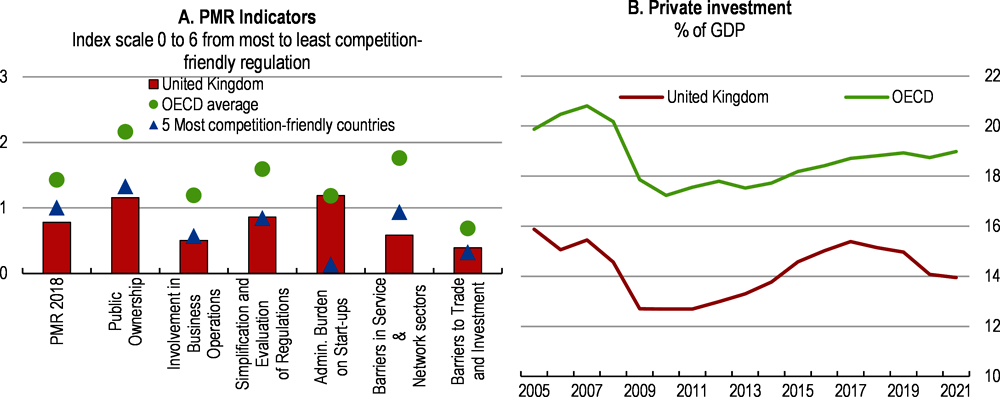

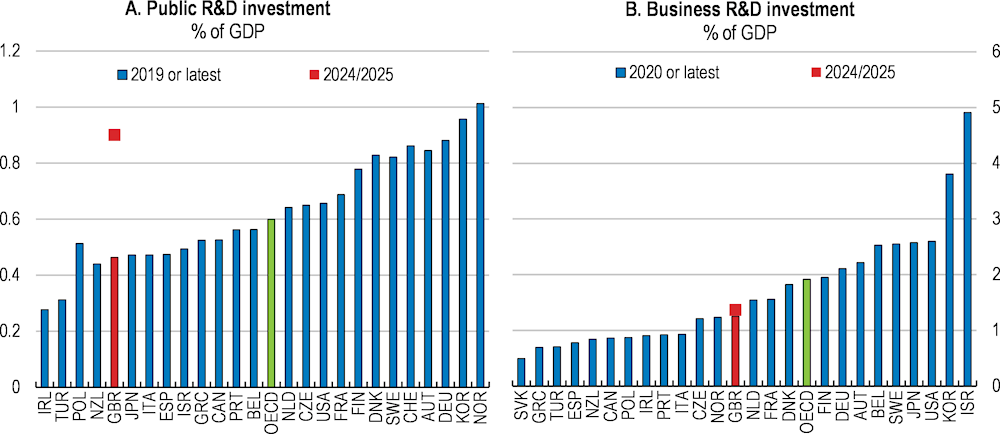

Productivity growth in the United Kingdom has been sluggish since the global financial crisis (Figure 1.19Figure 1.19, Panel A). Previous OECD Surveys identified a range of issues, such as skill mismatches, low innovation and knowledge diffusion, low digital adoption in particular by SME’s, as well as low private and public investment (Kierzenkowski, Machlica and Fulop, 2018[37]; OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2017[31]). Low aggregate productivity in the United Kingdom is also a product of large regional disparities, which have further increased over the last decade (Figure 1.19Figure 1.19, Panel B). Structural reforms to raise productivity across regions will be crucial for managing shocks and the transition to net zero over the coming years as it will to help sustain employment and wages and thereby living standards and well-being.

Figure 1.19. Productivity performance has been poor since the financial crisis

Note: Panel A: Labour productivity refers to real GDP divided per total hours worked. Pre-crisis labour productivity trend growth is calculated between 1972 Q1 and 2007 Q4, and is projected from 2008 onwards. Panel B: The GDP per capita of the top and bottom 20% regions (TL3) are defined as those with the highest/lowest GDP per capita until the equivalent of 20% of national population is reached.

Source: OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database); and OECD Regions and Cities at a glance 2020.

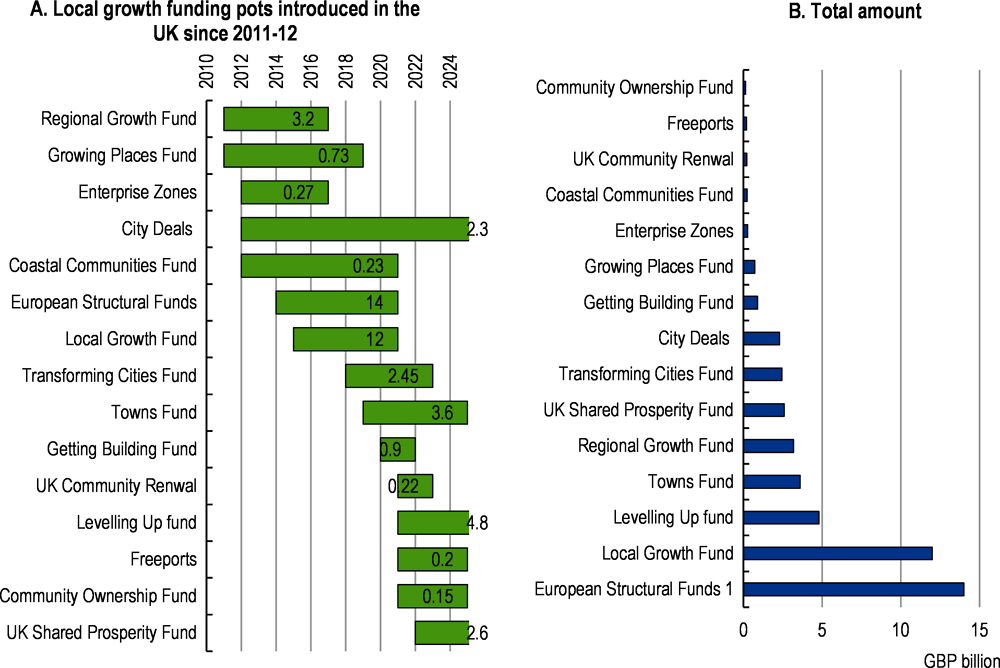

After a decade of low public investment and low productivity growth, the government recognises the need to deliver higher productivity through the private and public sector with three priorities: capital, people and ideas (HM Treasury, 2022[38]). It therefore developed an ambitious plan to support productivity in the United Kingdom and aid the digital and green transition. The government’s Plan for Growth outlines an agenda to facilitate structural transformation towards greener and more inclusive growth, centred on investments in infrastructure, skills and innovation, as well as leveraging the new opportunities from leaving the European Union (Box 1.7). The Plan for Growth replaces the 2017 Industrial Strategy continuing with a tendency to change policy frameworks as new governments come in. Some long-term stability was maintained by keeping the National Infrastructure Commission and continuing the Industrial Strategy’s sector deals, but the Industrial Strategy Council that oversaw the progress on the Industrial Strategy has been disbanded. An overarching independent body overseeing progress and implementation of all individual elements of the Plan for Growth is missing, but could help to increase transparency and accountability and ultimately stimulate private investment.

Box 1.7. Plan for Growth – Build back better