The relationship between government and the public is also shaped by government decision-making processes and outcomes on complex policy issues. This chapter explores public perception of government competencies and values in relation to complex decision-making. Specifically, it explores how people rate government reliability in emergency preparedness, in balancing the interests of current and future generations, in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, and regulating artificial intelligence. The chapter also discusses the extent to which people perceive that decision-making is carried out with integrity for the public good rather than for private interests and that people can influence decision-making. Institutional safeguards, such as parliament’s ability to hold the government accountable, are also considered. Finally, the chapter shows the ways in which people in OECD countries participate in political activities, as well as their expectations of government's openness and responsiveness to public input.

OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results

4. Trust in Government on complex policy issues

Abstract

The relationship between government and citizens is defined not only through the day-to-day interactions with the public, but also through the planning, design and decision-making process of policies that address major challenges. In a context of multiple crises, people expect public institutions in general and governments in particular to respond at scale and speed, but also to strengthen democratic resilience, by enhancing competences to deliver long-term sustainable gains in well-being and by maintaining high-quality institutions ensuring representative government and meaningful engagement, respect for fundamental rights and checks on government.

Findings from the OECD Trust Survey suggest that a majority believe that government institutions can reliably manage large scale emergencies to protect people’s lives. Together with the high satisfaction in public services, this suggests that there exists a relatively high store of faith in the government’s ability to fulfil this part of its core functions. This stock of faith shrinks when it comes to assessing the ability of government to adequately address policy issues with long-term implications, difficult trade-offs, interconnected domestic and global governance, and large unknowns, such as climate change and the emergence of artificial intelligence. While some of the less positive results are related to the inherent uncertainty and complexity associated with these policy areas, concerns about a lack of integrity and fairness both of high-level political officials and government policy overall can contribute to citizens’ unease with government’s ability to take policy decisions both competently and ethically.

In democratic systems, people rightly expect that their political system fosters checks and balances within and between government branches and through elections. While a higher share of people believe that parliament can hold the executive government accountable than have positive assessments for other integrity measures, the share that does so remains below 40%. Trust Survey respondents express low confidence in their own capacity to participate in politics and in the political system giving people like them a say in what government does. Many are also sceptical of the ability or willingness of government to not only listen to them, but act upon what they have to say. Maintaining the well-perceived performance with regards to emergency readiness, ensuring that parliament can exercise its function as a check on the executive, investing in integrity measures against undue influence and ensuring that citizens deliberative and consultative processes, where they exist, are well-integrated into the broader decision-making system of representative democracy could all serve to strengthen confidence that policy making is competent and values-based and ultimately improve trust in the national government and parliament.

4.1. A majority of people see public institutions as reliable in case of emergencies

In recent years, several crises have threatened the wellbeing of people worldwide, but investments in emergency preparedness appear to bear some fruit. In many instances, governments in OECD countries have responded at speed and scale to economic, public health and security shocks, and seemed to have contained their impact on trust levels. In part, this may be due to the advances that OECD countries have made in recent years in assessing, preventing, and responding to crises or disaster which entail large socio-economic impacts (OECD, 2023[1]).

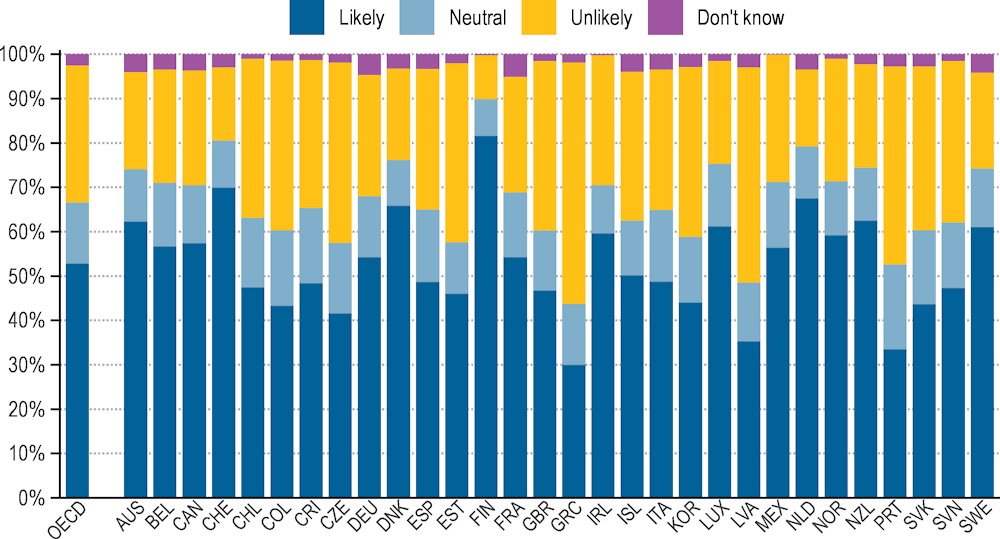

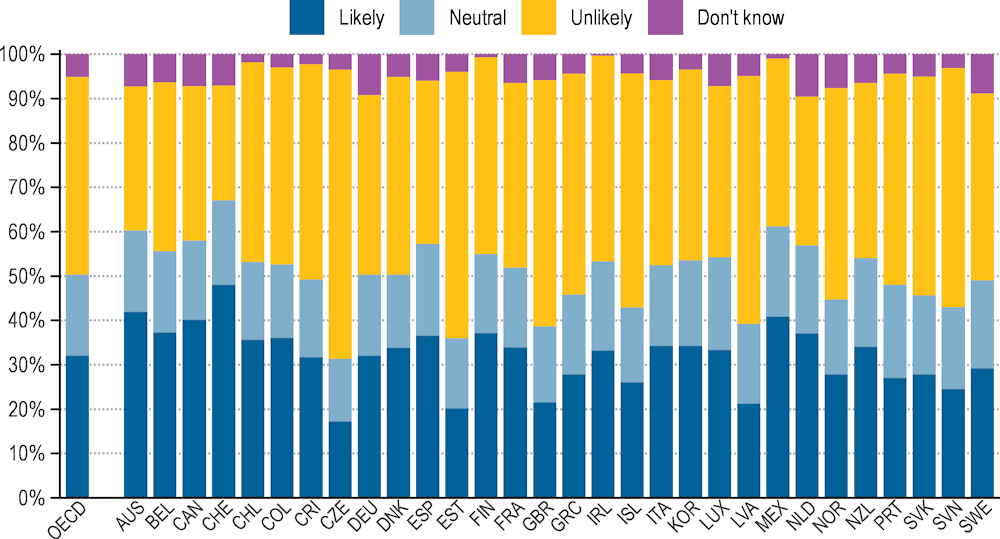

Many people express a favourable view of governments' ability to respond to crises. On average across countries, 53% express confidence that their government would be prepared to protect people’s lives in the event of a large-scale emergency, while 31% think it would not be prepared (Figure 4.1).

Unlike in 2021, where the question referred to the preparation of governments to protect lives in the event of a new serious contagious disease, the 2023 question does not specify the type of emergency. Evidence from cognitive testing carried out by the Australian Bureau of Statistics prior to the implementation of the survey suggests that respondents think of different types of emergencies when answering this question (OECD, Forthcoming[2]), including pandemics and natural disasters. Despite the more open-ended nature of the question, the share of people who are confident in government preparedness increased across the countries that participated in both waves, rising from 51% in 2021 to 55% in 2023 (Figure 4.7).

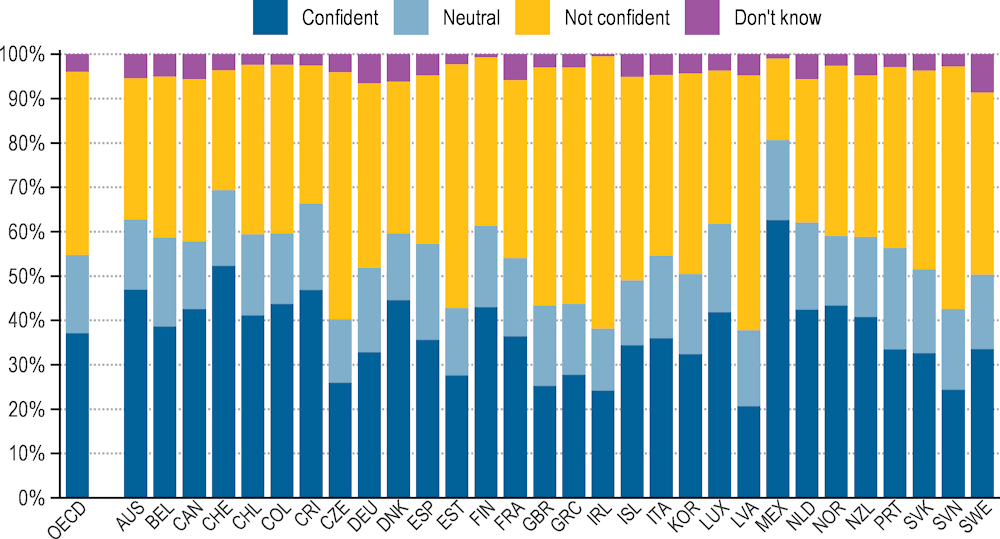

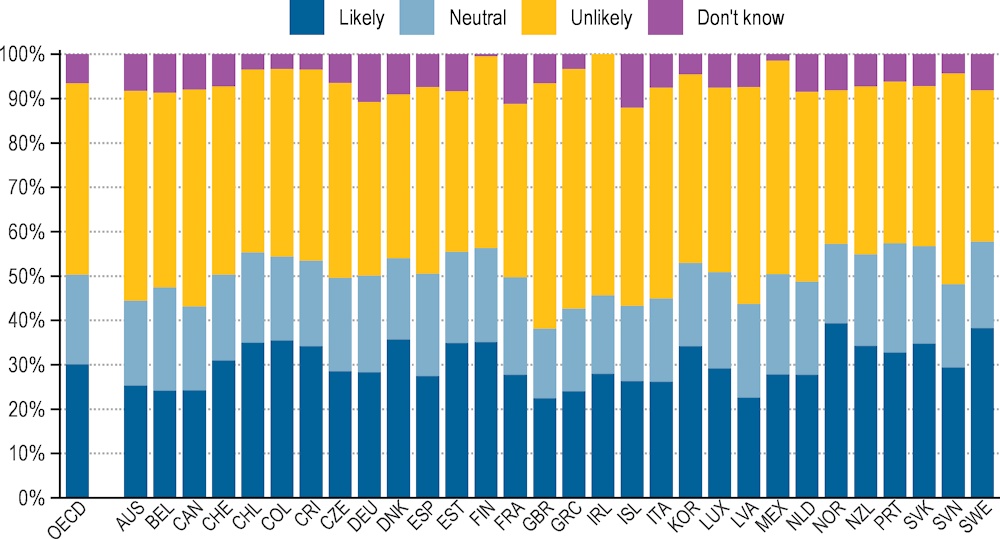

Figure 4.1. A majority says government institutions would be ready to protect lives in a large-scale emergency

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government institutions are ready to protect people’s lives in a large-scale emergency, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If there was a large-scale emergency, how likely do you think it is that government institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

In a multi-crisis environment with a rising sense of insecurity globally (UNDP, 2022[3])), the fact that a majority of people have faith in the emergency preparedness and reliability of their public institutions indicates that the actions of OECD governments during recent crises have reassured the majority of their populations. However, differences across countries are relatively high compared to other questions. In Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, more than two thirds find it likely that institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives, while in Greece, Latvia, and Portugal, the share is at or below 35%.

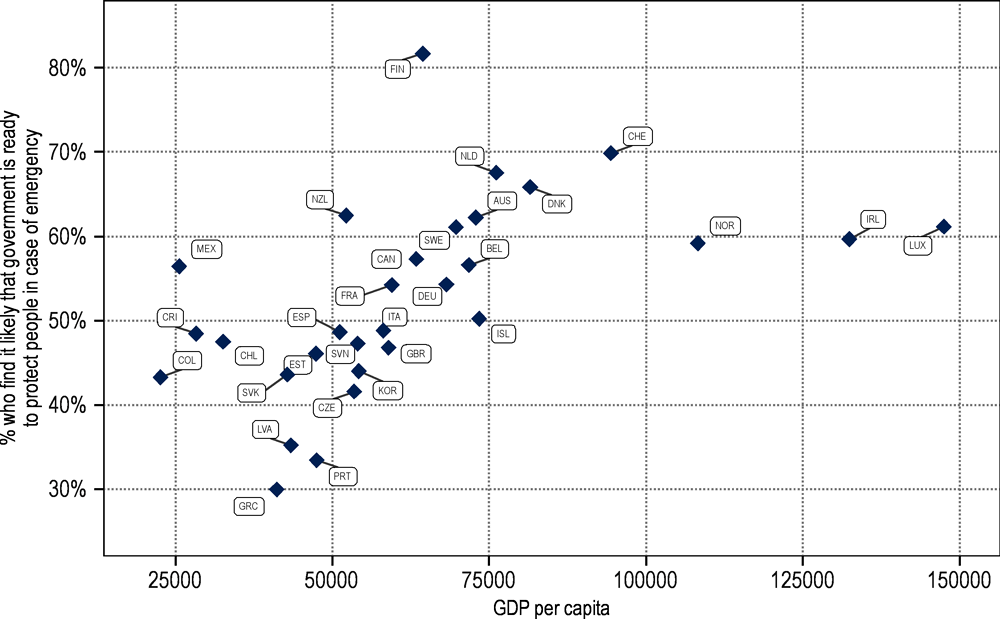

Perceptions in this regard may be due to a combination of reasons, including perceived vulnerability of the country in the current context, evaluation of previous experiences, and different assessments of the resources and capacity of a country. Indeed, an earlier analysis showed that over the 1995-2010 period, OECD countries with lower per-capita income experienced a larger loss of life from disasters than higher-income countries (OECD/The World Bank, 2019[4])). In general, there does appear to be a linear relationship between improving perceptions of emergency readiness and rising levels of GDP per capita (Figure 4.2). However, the relationship is not perfect as Latin American countries and Finland perform better than their GDP per capita would suggest.

Figure 4.2. On average, a higher share of people in higher-income countries compared to lower-income countries believe government institutions are prepared for emergencies

Share of population in country who find it likely that government institutions are ready to protect lives in case of a large-scale emergency (y-axis) and purchasing power adjusted GDP per capita (x-axis), 2023

Note: The figure shows the country average of the share of respondents who selected likely (responses 6-10 on the 0-10 scale) to the question “If there was a large-scale emergency, how likely do you think it is that government institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023 and OECD (2024), “GDP – Expenditure Approach: Per Head, US $, current prices, current PPPs, seasonally adjusted”, Quarterly National Accounts.

4.2. Government is seen as less reliable in addressing complex policy challenges involving many unknowns or trade-offs

Crisis management and preparation require public institutions to make decisions amidst uncertainty. This complexity and uncertainty are compounded when dealing with complex policy issues which have long-term and global ramifications, as their potential impacts are even more difficult to assess. These inherent difficulties likely contribute to lower levels of confidence in the government’s ability to handle complex policy challenges such as new technologies, balancing the needs of current and future generations, or tackling climate change.

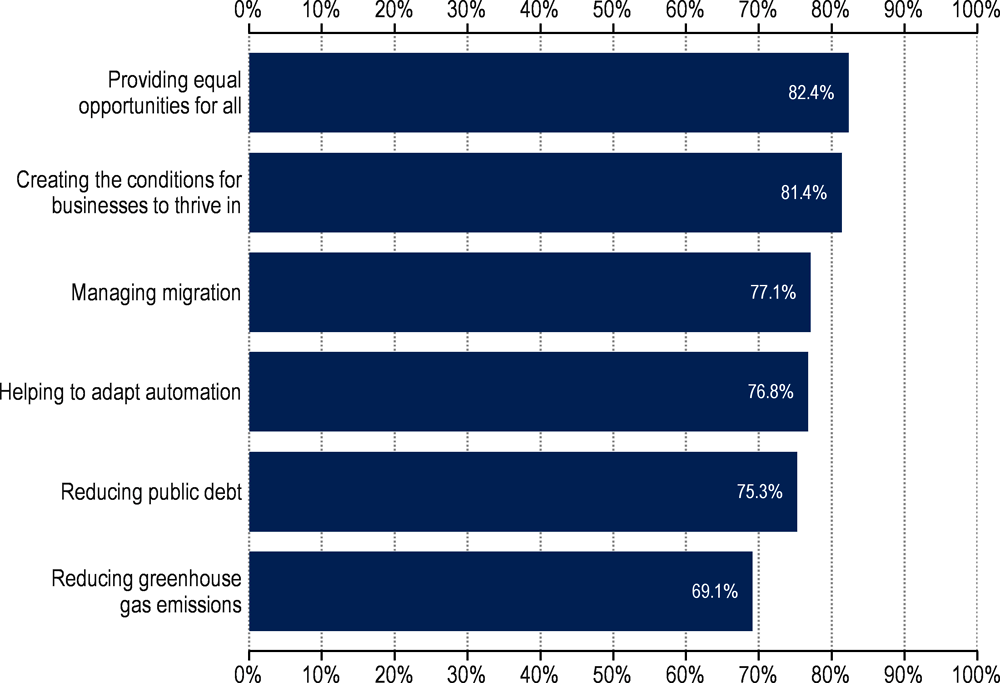

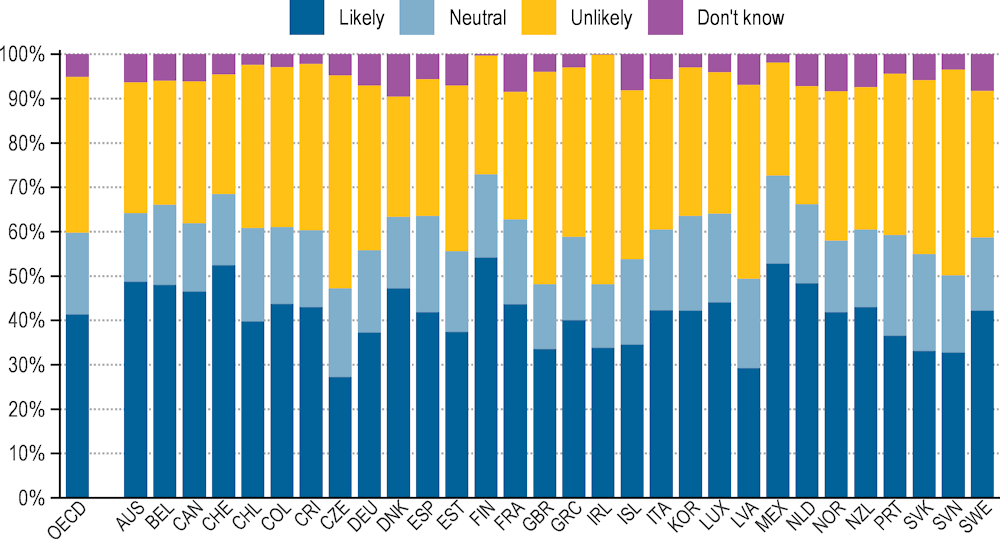

Public expectations regarding the governance and application of new technologies are high; on average across OECD countries, 77% of people think that helping workers to adapt to automation, digitalisation and new technologies should be highly prioritised in their country (Figure 4.3). Yet only four in ten people (41%) find it likely that the national government would adequately regulate new technologies, such as artificial intelligence and digital applications, and help businesses and citizens use them responsibly, while more than one third (35%) think it unlikely (Figure 4.4). Differences among countries on this question are relatively small.

Figure 4.3. Providing equal opportunities for all and creating the conditions for businesses to thrive are seen as policy areas that countries should prioritise

Share of population who think it is important that their country prioritises the respective goal, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure shows the unweighted OECD average of the share of population who indicate the goal is important (responses 6-10 on a 0-10 scale) when answering the question “How important do you think it is that each of the following goals are prioritised in [COUNTRY]?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

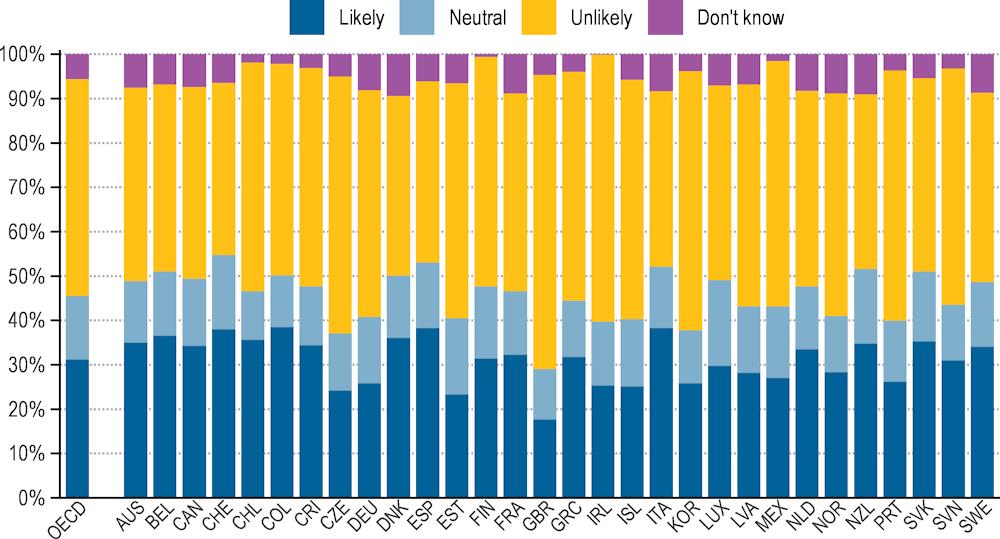

Figure 4.4. More than one third think it unlikely that government can regulate new technologies appropriately and help businesses and citizens use them responsibly

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government will regulate new technologies appropriately and help businesses and individuals use them responsibly, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If new technologies (for example artificial intelligence or digital applications) became available, how likely do you think it is that the federal/central/national government will regulate them appropriately and help businesses and citizens use them responsibly?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

In addition, slightly more than one third of people (37%) believe that government can adequately balance the needs of different generations, while 41% do not believe so (Figure 4.5). Results vary among countries, and Mexico and Switzerland are the only countries in which more than half of the adult population are confident that the government adequately balances the interest of current and future generations.

Perceptions of government capacity to respond to emergencies and promote intergenerational fairness in their policy making closely tie in with trust in public institutions. When analysing a diverse set of drivers of trust, public confidence that the government can balance the interests of current and future generations emerges as having the second-highest association with trust in the national government, and is likewise a significant driver of trust in the national parliament. The belief that the government is ready to protect lives is also associated with an increased likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in the national government (see Chapter 1 and Annex A).

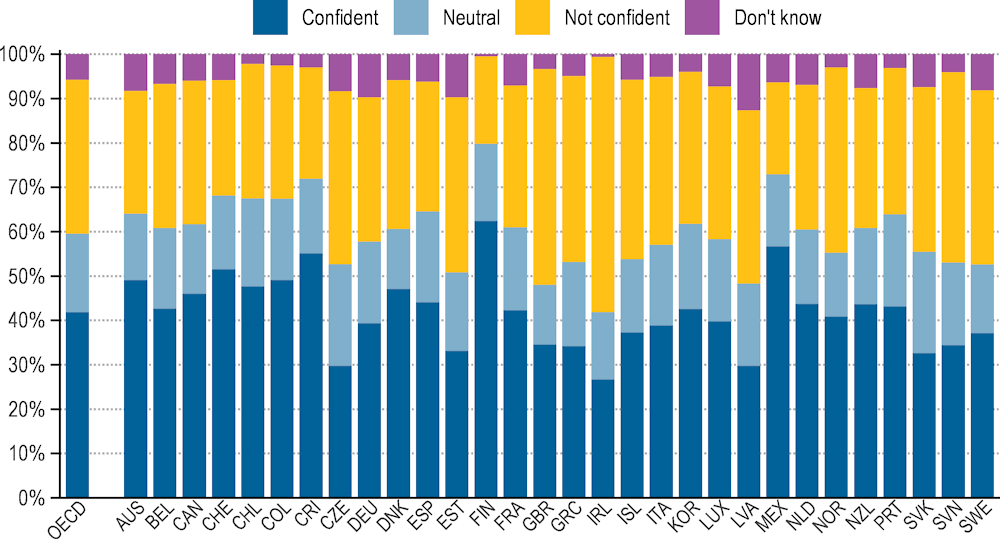

Figure 4.5. There are more people who find it unlikely than who find it likely that government can balance the interests of current and future generations

Share of population reporting different levels confidence that the national government can adequately balance the interests of current and future generations, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that the national government adequately balances the interests of current and future generations?”. The “confident” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “not confident” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

On average across countries, 21% of individuals indicate that climate change and other environmental issues constitute one of the top three concerns in their country (Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1). With regards to public perception that their country will be able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the coming ten years, 42% are confident that the country will succeed, compared to 35% who lack confidence (Figure 4.6). These results suggest people appear to be more optimistic than the evidence should allow as current predictions indicate that greenhouse gas emissions will not reduce to limit global warming to 1.5C (UNEP, 2022[5]).1 This discrepancy is likely explained by several factors: People may respond on whether they expect that overall emissions can be reduced rather than that international agreements or carbon neutrality are met. In addition, other factors such as the technical nature of the topic, the effect of political communications that proclaim to make carbon neutrality a strategic compass (Green Deal, Paris Agreement...), and limited deciphering by the media on the implementation of these measures and their effectiveness could also have contributed to this result.

Figure 4.6. An average of four in ten are confident their country will reduce greenhouse gas emissions

Share of population reporting different levels confidence that their country will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the next ten years, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that [COUNTRY] will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the next ten years?”. The “confident” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “not confident” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

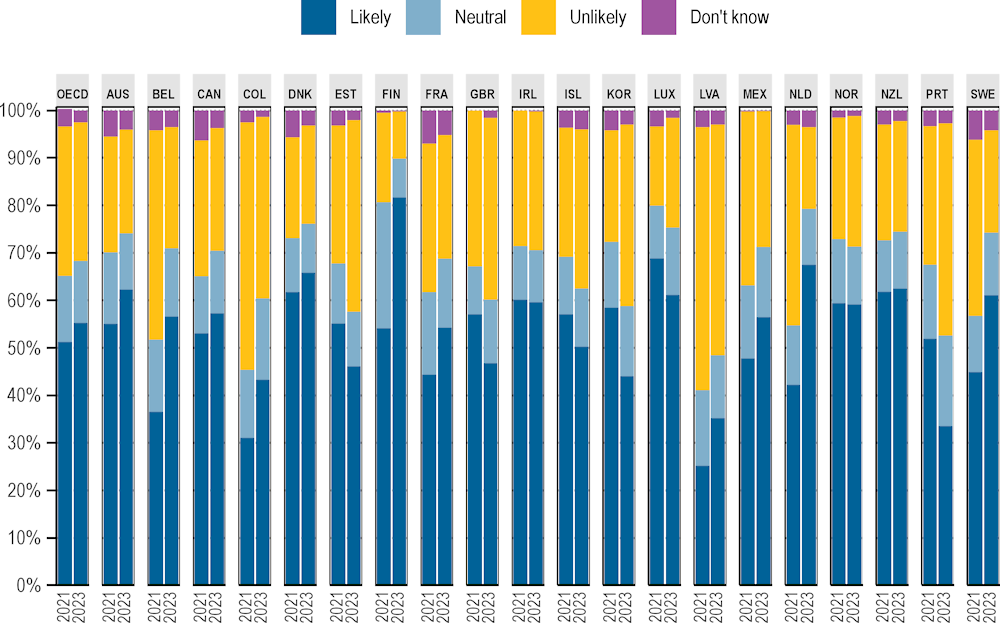

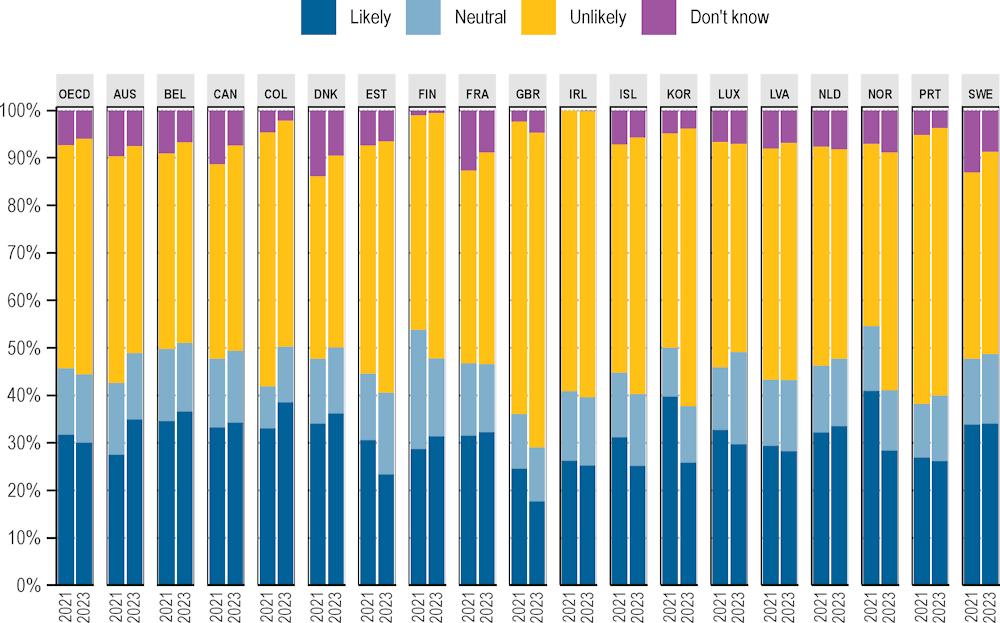

Box 4.1. Spotlight on changes: Confidence in government’s emergency preparedness and in reducing country’s greenhouse gas emissions

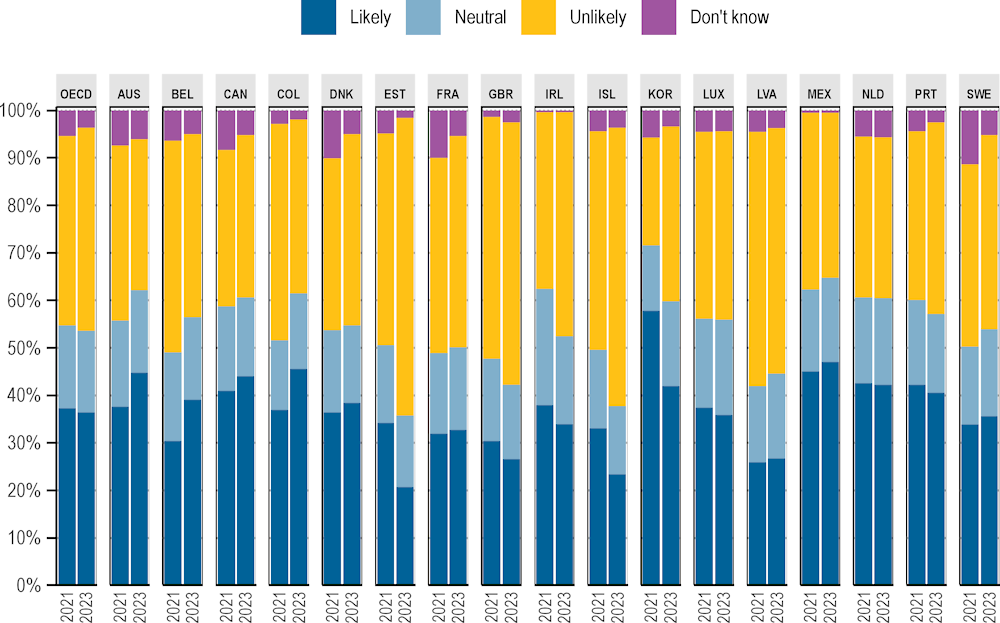

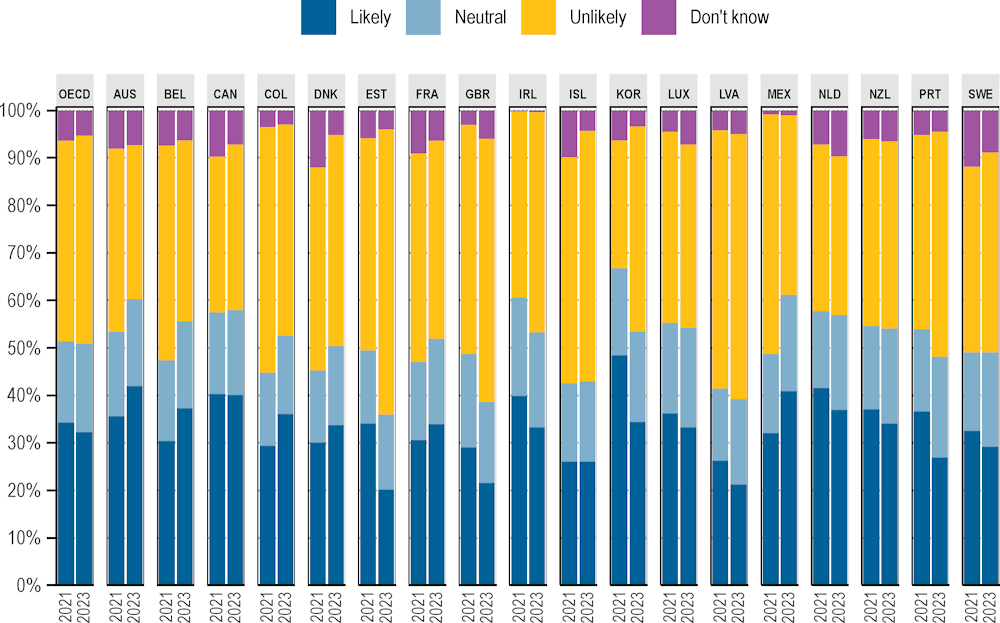

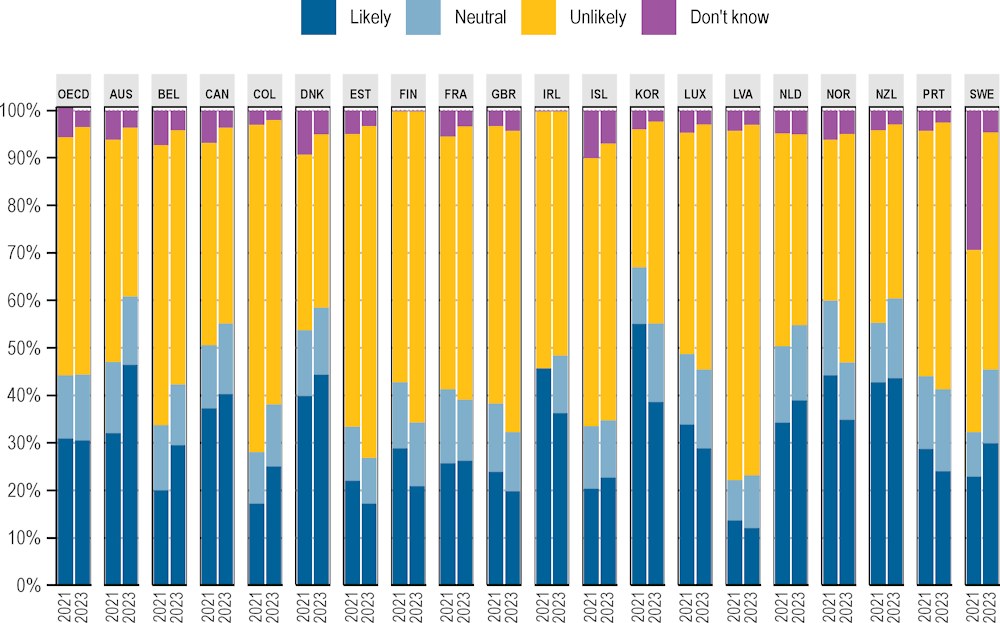

Despite a more open-ended question on emergency preparedness in 2023, the average share of the adult population who believe government institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives has risen, both on average across the OECD and in the majority of countries, with particular high gains in Finland (Figure 4.7). Compared to the 2021 survey, confidence in the achievement of emission reductions also appears to have slightly increased, rising from 36% to 40% in the countries with available information for both years (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.7. Confidence in governments’ emergency preparedness increased in a majority of OECD countries

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that their government is ready to protect people’s lives in case of emergency (2023) or a new serious contagious disease (2021)

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question concerning the emergency preparedness of their government. In the 2021 wave, the question asked, “If a new serious contagious disease spreads, how likely or unlikely do you think it is that government institutions will be prepared to protect people’s life?”. In the 2023 wave, the question wording changed to, “If there was a large-scale emergency, how likely do you think it is that government institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Norway: ‘’If a new and serious infectious disease were to start spreading in Norway, how likely is it that the authorities would be sufficiently prepared to be able to protect the citizens’ lives and health?’’ and in Finland ‘’If an alert due to the appearance of a new disease is raised, do you think that existing public health plans would be effective?’’. In both waves, the “likely” proportion represents the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

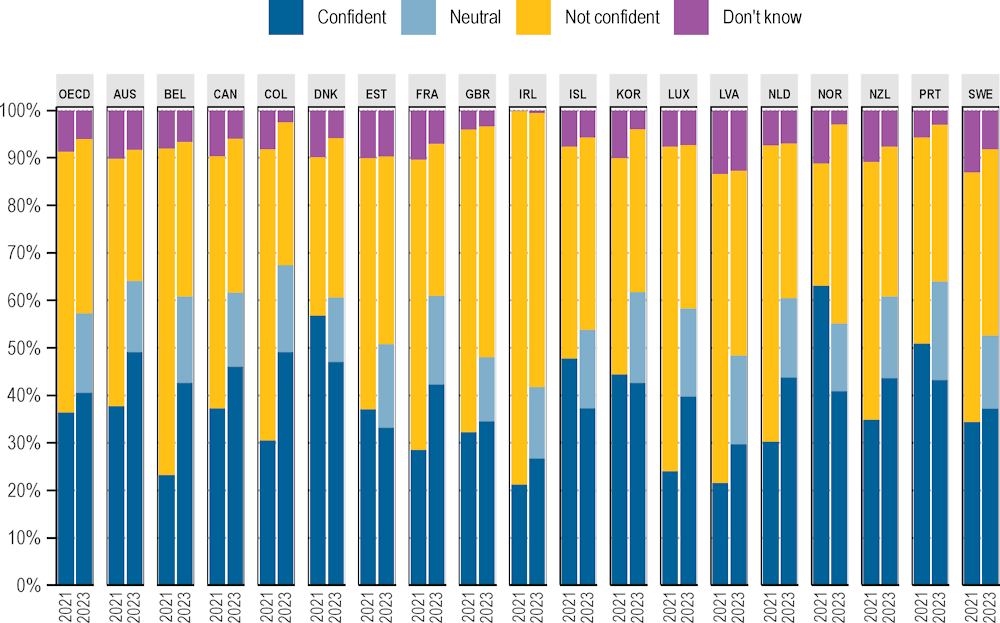

Figure 4.8. Confidence in their country’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions slightly increased in many countries

Share of population reporting different levels of confidence in government’s ability to succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the next ten years

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses among all respondents to the question “How confident are you that [COUNTRY] will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the next 10 years?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Norway: ‘’To what extent do you agree or disagree that public authorities do enough to protect the environment?‘’. The answer scale differed between 2023 and 2021. In 2023, the "confident" proportion aggregates responses from 6 to 10 on the scale; "neutral" corresponds to a response of 5; "not confident" aggregates responses from 0 to 4; and "don't know" was a separate answer choice. In 2021, the scale comprised four answer options. In Ireland the response scale included five options instead of only four in 2021, which were rescaled to match the cross-country data with four options (‘’quite confident’’ and ‘’very confident’’ became ‘’somewhat confident’). Consequently, in 2021, the "confident" proportion aggregates responses for "somewhat" and "completely"; "not confident" aggregates responses for "not at all" and "a little". "OECD" presents the unweighted average of responses across countries, for the listed countries where the variable is available in both 2021 and 2023. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

4.3. Most people feel decision-making favours private sector interests over the public interest

Policy preferences and conceptions of fairness can vary from person to person. Despite these varying perspectives and preferences, citizens universally value decision makers who are guided by considerations of what is best for society. Findings from the Trust Survey, however, reveal concerns that private interests exert an oversized influence on the government. There is a general perception that public decisions over policies may be repeatedly diverted away from the public interest towards special interests and interests of the “powerful”, undermining democratic values and exacerbating a sense of exclusion and inequalities from the democratic political system.

On average across countries, 43% of respondents say it is likely that the national government would accept the demands of a corporation promoting a policy beneficial to their industry but harmful to the society as a whole, and only three in ten respondents (30%) believe that the government would refuse a corporation’s demands, with small difference among countries. However, it also needs to be noted that the share of respondents who give a neutral response (20%) or who do not know (7%) is unusually high for this question (Figure 4.9).

Figure 4.9. Fewer than one in three people find it likely that the government would refuse a corporation’s demand if it went against the public interest

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that the government would refuse the corporation’s demand, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If a corporation promoted a policy that benefited its industry but could be harmful to society as a whole, how likely do you think it is that the national government would agree to the corporation’s demand?”. For ease of analysis, the direction of the answers were turned around, to match a share of likely with a positive meaning. In detail, the share of ‘likely the government agree to’ of the original question corresponds to ‘unlikely government refuses’ above. The “likely” proportion is therefore the aggregation of responses from 0-4 on the scale of the original question; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 6-10; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

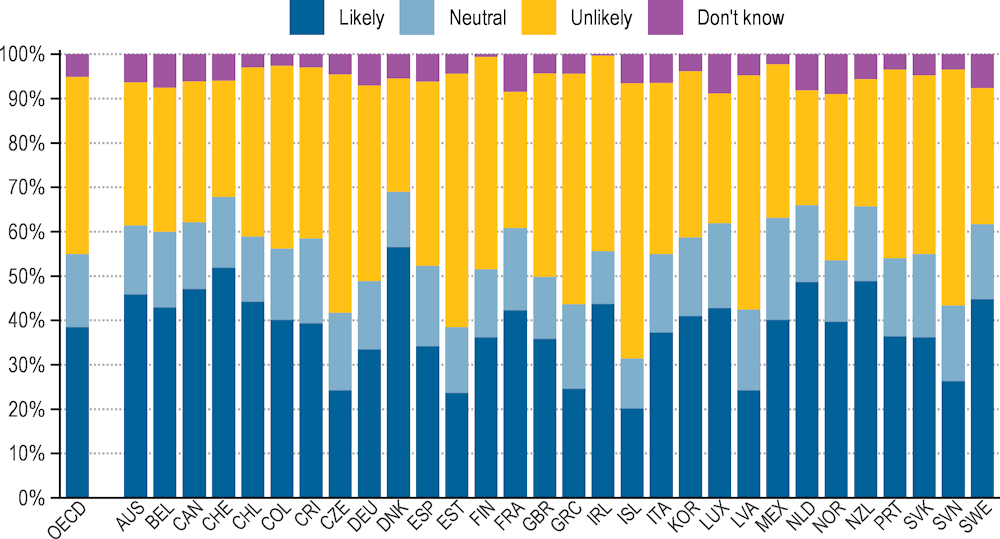

Across OECD countries, there is also a widespread scepticism about the integrity of high-level political officials and concerns over undue influence. On average, almost half of respondents (49%) predict that a high-level political official would grant a political favour in exchange for the offer of a well-paid private sector job; while close to a third (31%) find it likely he or she would refuse to grant the favour (Figure 4.10). For both integrity questions, the variation in perceptions between countries is smaller than for most other public governance drivers. In particular, there is no country where at least four in ten respondents find it likely that the political official or national government would refuse to grant a political favour or enact a policy that might be against the public interest. Moreover, in the 18 countries with available information in both years, the share of people who believe that a high-level political official would refuse to grant a favour decreased from an average of 32% in 2021 to 30% in 2023 (Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.10. Nearly one in two doubt that a high-level political official would refuse to grant a political favour in return for a well-paid private sector job

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that a high-level political official would refuse to grant a political favour, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If a politician was offered a well-paid job in the private sector in exchange for a political favour, how likely do you think it is that they would refuse it?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

While lobbying and other influence practices are a natural part of the democratic process, the manner in which these practices take place is critical to democratic resilience. Lobbying by business and other interest groups can serve to bring diverse perspectives to the attention of policy makers. However, if special interest groups disproportionately influence decision-making or use misleading evidence to advance their own interests or manipulate public opinion, public policies and democracy itself suffer. The same is true if political decision makers breach political integrity standards and use their position to further the commercial or political interests of particular groups (OECD, 2023[6]). Yet many OECD countries lack the full safeguards to prevent corruption in lobbying and conflict-of-interest situations; and where they exist, these safeguards are not always applied: On average across 28 OECD countries, only 38% of standard regulatory safeguards on lobbying are in place, and only 35% are implemented in practice. Likewise, as measured against OECD standards, regulations in OECD countries to safeguard against conflicts of interest meet 76% of criteria on average, but their actual implementation only meet 40%. Despite strong regulatory requirements, many countries often fail to track whether interest and asset declarations have been submitted, or have weak procedures to verify their content (OECD, 2024[7]).

Box 4.2. Spotlight on changes: Integrity of high-level political officials

On average across countries, the share of those who find unlikely that a high-level political official would refuse to grant a political favour has increased by three percentage points between 2021 and 2023, particularly in Korea and Norway.

Figure 4.11. The share who find it likely that policy makers act with integrity is slightly declining

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that a politician would refuse to grant a political favour, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If a politician was offered a well-paid job in the private sector in exchange for a political favour, how likely do you think it is that they would refuse it?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Finland ‘’If a large business offered a well-paid job to a high level politician in exchange for political favours during their time in office, do you think that he/she would refuse this proposal?’’. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

4.4. Institutional checks and balances, which are intended to ensure fair decision-making, are perceived as inadequate

In democracies, the political system is meant to safeguard public interest in policy decision making through checks and balances between the branches of government, and through elections.

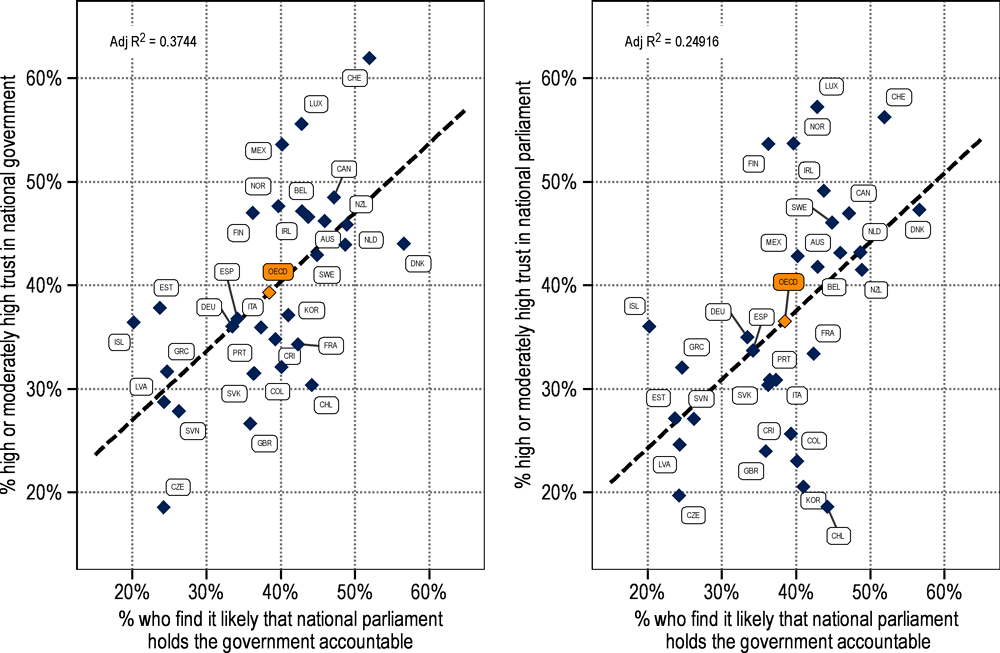

Checks and balances, along with constitutional safeguards, ensure that no single branch of government, including the executive national government, can take decisions without the oversight of the other branches of power. The Trust Survey finds that 38% of people believe that the parliament can effectively hold the government accountable, for instance by questioning a minister or reviewing the budget, and a slightly higher share (40%) is sceptical (Figure 4.12). Only in Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Switzerland around half of the adult population are confident in the oversight function of parliament. Similarly regarding checks and balances and the relationship between branches of government, the 2021 Trust Survey found that about four in ten (42%) believed that that a court in their country would always make decisions free of political influence (OECD, 2022[8]).

The average share of respondents who find it likely that the national parliament holds the national government accountable in this way (38%) aligns closely with the average share of those with high or moderately high trust in the national parliament (37%). However, while this applies on average, at the individual country level, the share who trust the national parliament and who believe in its ability to hold the national government accountable is not as closely related.

Figure 4.12. On average, close to 40% find it likely that the national parliament holds the national government accountable

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that the national parliament holds the national government accountable, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “How likely do you think it is that the national parliament would effectively hold the national government accountable for their policies and behaviour, for instance by questioning a minister or reviewing the budget?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Confidence in the oversight function of parliament is correlated with trust in the national government at the country level, meaning that in countries where more people believe in the checks and balances between different branches of government, trust in the national government is higher. The same relation holds, albeit less strongly, between confidence in the parliament oversight function and trust in parliament (Figure 4.13).

Figure 4.13. Having a higher share of people who believe in the ability of the national parliament to exercise checks on the national government is associated with higher levels of trust in the national government and parliament

Share of population in country who find it likely that the national parliament holds the government accountable (x-axis) and high or moderately high trust in the national government (left-hand axis, left chart) and in the national parliament (left-hand axis, right chart)

Note: The scatterplot presents the share of “high to moderately high trust” responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government/national parliament?” on the y-axis of the left and right chart, respectively. The y-axis presents the share of “likely” responses to the question How likely do you think it is that the federal/national parliament would effectively hold the federal/central/national government accountable for their policies and behaviour, for instance by questioning a minister or reviewing the budget?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Of course, one of the biggest challenges in democracies is to define and pursue “public interest” in diverse societies with people of varying needs and preferences. People generally expect the parliament to fairly balances the interests of different regions or groups in society. Here, 36% find it likely that it would adequately do so when debating a new policy, while 41% find it unlikely (Figure 4.14). Among all the variables measuring people’s public governance perceptions, this is the single most important one for trust in the national parliament.

Figure 4.14. Slightly more than one third believe that parliament fairly balances the interests of different groups when debating a policy

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that national parliament fairly balances interests of different groups, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If the national parliament debated a new policy, how likely do you think it is that it would adequately balance the needs of different regions and groups in society?. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

4.5. Government decision-making is seen as unresponsive to the public, weakening the meaning of representative democracy

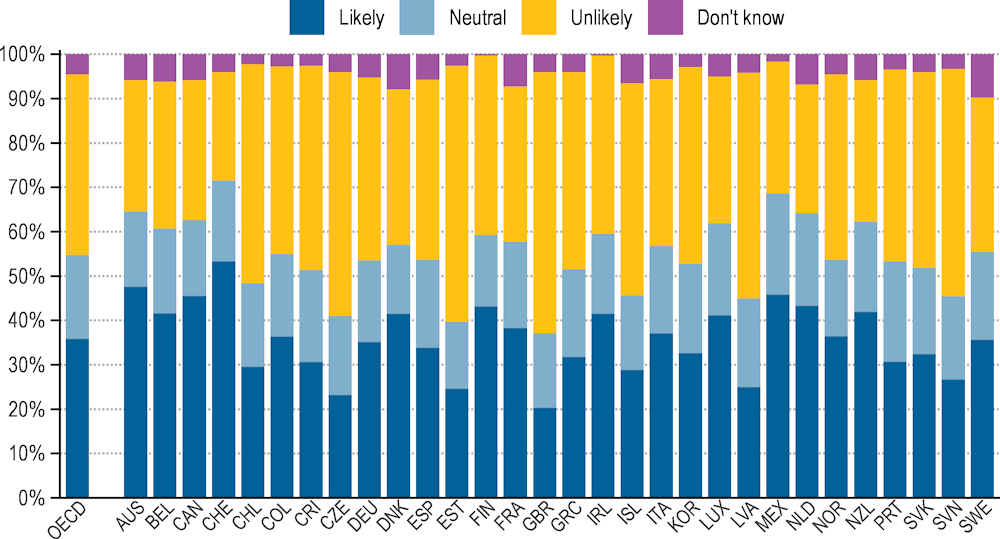

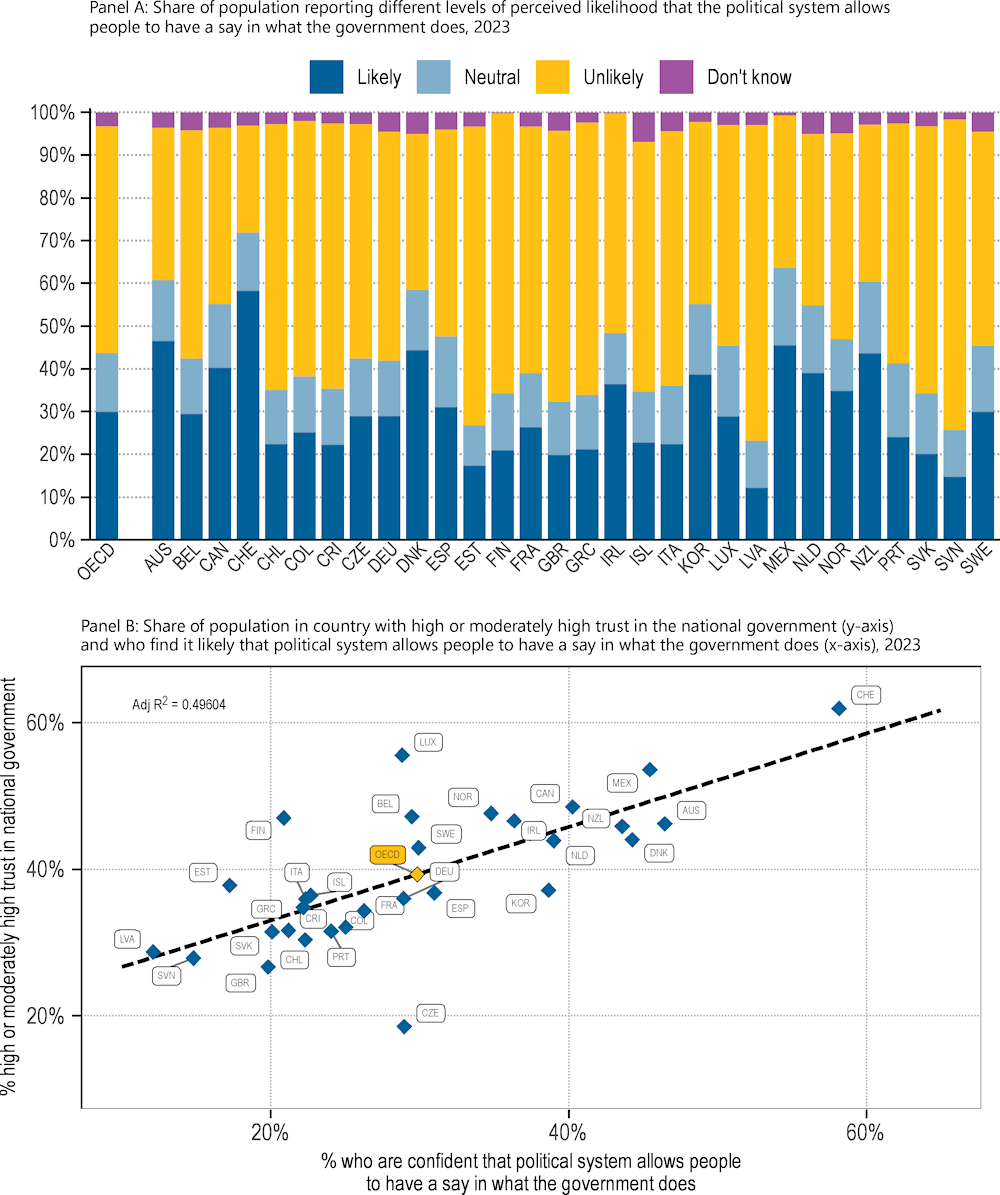

In democracies, the main instrument for the public to hold government and parliament accountable are free and fair elections, but not all individuals feel equipped to participate in the political system. On average, 82% indicated that they had voted in the last national elections. High participation rates, nonetheless, do not mean that people necessarily believe that they are able to influence politics through the electoral system. In fact, only 40% are confident in their own ability to participate in politics, and an even lower share (30%) believe that the political system in their country allows people like them to have a say in what government does (Figure 4.15, A). On the opposite side, 53% believe that the political system does not allow them to have a say. Out of the approximately 600 million adults across the 30 participating OECD countries, this therefore corresponds to nearly 320 million people who feel that they lack political agency and who will be much less likely to have high or moderately high trust in the national government. Having a say is highly correlated with trust in the national government at the country level (Figure 4.15).

Figure 4.15. Higher confidence in having a say is correlated with higher trust in the national government

Note: Panel A: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question ‘’How much would you say the political system in [COUNTRY] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?’’. Panel B: The chart illustrates the percentage of respondents reporting “likely” to the question: “How much would you say the political system in your country allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?” or answering “high or moderately high trust” to the question: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust national government?”. The “likely” or “high or moderately high trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Many see governments as unresponsive to public feedback on policies. Even when feedback is solicited, people do not always feel that opinions are consequently taken into account in decision-making. Slightly more than one third (37%) think that if over half of the people expressed a view against a national policy, it would be changed (Figure 4.16). This share ranges from one fifth in Estonia to over half in Switzerland. Slightly below one third, in turn, think that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in a public consultation on reforming a policy area (Figure 4.17). Moreover, perceptions on both variables have worsened on average since 2021 (Figure 4.20 and Figure 4.21). At the cross-country level, the share who find it likely that government is open to the feedback according to one measure is highly correlated with the other. Perceptions that opinions expressed in a public consultation influence policies and in particular the perception of having a say in government policies are positively associated with increased trust in the national government (see Chapter 1 and Annex A). Both variables also have a positive relationship with trust in the national civil service, as does having a political voice for trust in the national parliament.

Figure 4.16. Slightly more than one in three think that government would change a policy in response to a majority public opinion

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government would change a national policy if over half of the people expressed a view against it, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If over half of the people in [COUNTRY] clearly expressed a view against a national policy, how likely do you think it is that it would be changed?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Figure 4.17. Slightly fewer than one in three think that government would adopt the opinions expressed in a public consultation

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government would adopt opinions gathered in public consultation, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you participated in a public consultation on reforming a policy area, how likely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the consultation?”. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Support for more consultative and deliberative processes with citizens seems to be a prevalent response to this sense of exclusion, lack of political agency, and unresponsiveness of government. There are many ways of involving citizens in decision making, but where governments need to focus is on how meaningful these consultations are. Consulting citizens is not equivalent to consulting stakeholders. In stakeholder consultations, people are heard as representatives of a particular segment of society (private sector, public service users, civil society, academia etc.). It is well known in research that they may have different views as a stakeholder than as a citizen (OECD, 2022[9]): for example, a public service user may well say that the public service should receive more funds, but as a citizen, they may prioritise a different sector of the economy. While stakeholder consultation aims at improving the quality of a policy measure, citizens’ engagement is a democracy-enhancing process and involves more responsibility of government to follow up on the results of the consultation.

The most extensive consultation mechanism is of course the referendum, as it is open to all citizens or residents with the right to vote. As of now, the availability and use of the referendum at the national, rather than regional or local level, differs quite strongly from country to country. The OECD country with the most widespread use of referendums is Switzerland, where laws on referendums for different situations were introduced throughout the 19th and early 20th century (Schiller, 2024[10]). At the other extreme, in selected OECD countries such as Germany, Japan, Korea or the United States, national-level referendums either are not foreseen at all within the legal framework or only in very specific circumstances that have so far not yet been invoked. Most OECD countries are to be found in the middle, however, with direct democracy being possible at the national level under wider circumstances and a limited number of referendums having taken place at the national level. This for example includes Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Slovenia and the United Kingdom (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2008[11]). In many cases, these referendums are large political endeavors and not more routine citizens’ involvement mechanisms in decision making, although there are exceptions to this such as the well-known example of Switzerland.

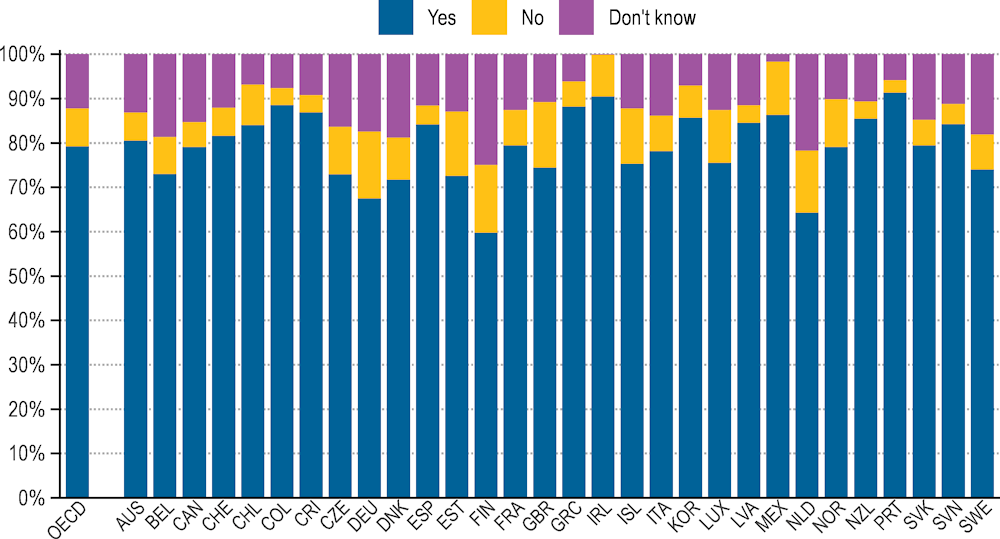

Despite these large differences in the availability and use of direct democratic instruments, people across the OECD almost uniformly agree that they would like to be able to vote on issues of national importance. On average, nearly eight out of ten (79%) of people indicated that they would like to be able to vote on issues of national importance; and fewer than one in ten (9%) would not like to be able to do so (Figure 4.18). Even in the countries with the lowest support for direct democracy, namely Finland, the Netherlands and Germany, at least 60% would like to have this option; and the share exceeds 90% in Portugal.

Figure 4.18. A majority is in favour of referendums on issues of national importance

Share of population who favour or do not favour the availability of a national referendum, 2023

Note: The figure shows the distribution of responses to the question “Do you think people in [COUNTRY] should be able to vote directly on specific issues of national importance in a referendum?”. ‘’OECD” presents the unweighted average of responses across countries.

Source: 2023 OECD Trust Survey.

These results in part reflect an inherent challenge of policymaking in representative democracies, made more acute in more digital societies where many more citizens have gotten used to expressing their views publicly and widely. Gathering people’s views can often yield contradictory results, making it particularly difficult for governments to then be responsive to all segments of the population (Fishkin and Laslett, 2008[12]). Indeed, "the people” are not a monolith who speak with one unified voice. Rather, they voice their perspectives at certain times, on distinct matters, through different means including elections, public discussions, various consultations, referendums, and engagements such as demonstrations. The task for governments lies in collecting, condensing, and interpreting these viewpoints, then addressing them in a clear and understandable way that acknowledges citizens’ views.

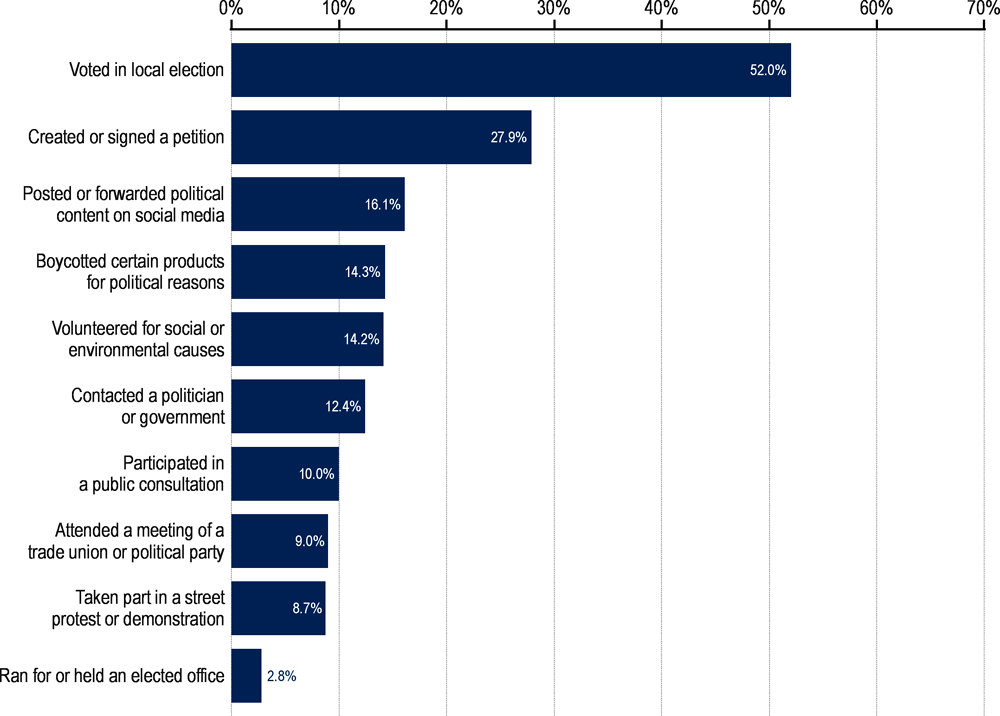

Trust Survey results provide some crucial insights into the patterns of political participation among the population in surveyed countries (Figure 4.19). The most common form of participation remains voting in national elections, with 82%. This is followed by voting in local or municipal elections (52%) and signing petitions (28%). Other forms of participation include posting political content on social media (16%), boycotting products (14%) and volunteering (14%). Fewer individuals have contacted a politician (12%), participated in a public consultation (10%), taken part in a demonstration (9%), or attended a meeting of a trade union or political party (9%). The least common form of participation is running for or holding elected office, with just 3%. Additionally, 23% of people reported not participating in any of the listed forms of political participation.

Figure 4.19. Less time consuming and confrontational modes of participation are more widespread

Share of population who participated the respective political activity over the last 12 months, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure shows the unweighted OECD average of the share of population who answered “yes” to one of the given activity in the question “Over the last 12 months, have you done any of the following activities?”

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Of course, these general trends at the OECD level obscure some interesting patterns within countries. For instance in Belgium, Canada and Korea, over 35% of people did not participate using any of the aforementioned channels (excluding voting in national elections). In Finland, Iceland and Ireland, more than 30% express their voice by boycotting products. In Ireland and Greece, around 18% took part in a protest, while this share sits between 13 to 15% in Chile, Spain, France and Iceland, significantly higher than the OECD average. These differing patterns of participation are important for governments to consider. Indeed, while offering individuals more opportunities to voice their opinions through formal mechanisms is important, listening to the voices expressed through people’s different modes of participation, even if they are informal, is necessary to ensure people feel heard.

Age also plays a role in choice of participation mechanisms. On average across countries, young people (18-29) tend to vote less in national (68%), and local (41%) elections. Political activities such as taking part in a demonstration and posting or forwarding political content on social media are more frequent among the youth than the rest of the population. In some countries, there are some marked differences between the forms of political participation taken up by the younger cohorts. For example, in Ireland 51% of those under 30 said they shared political content on social media in the last year, compared to 28% of those 30 and older. Similarly in Germany, the share of people who volunteered for social or environmental causes is twice as high among the young than among those who are older, at 20 and 10%, respectively.

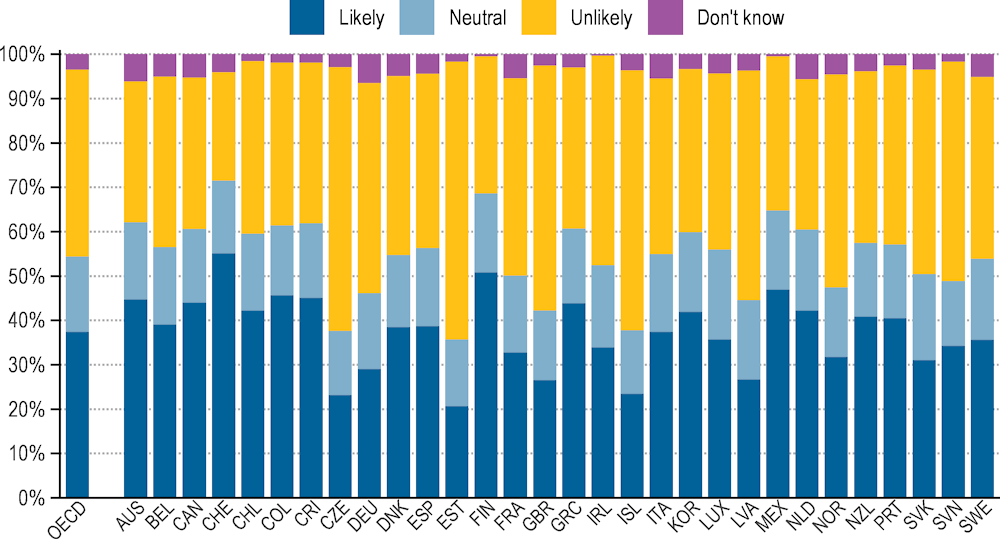

Box 4.3. Spotlight on changes: Openness, responsiveness in decision making and voice

On average, the share of people who think it likely that a national policy would be changed if a majority expressed a view against it slightly decreased, by one percentage point, since 2021. At the same time, the share increased in Australia, Belgium and Colombia by more than seven percentage points (Figure 4.20). Also, the share of people who are confident that the government would use inputs from a public consultation decreased since 2021, by 2 percentage points on average, particularly in Estonia, Korea, Portugal and the United Kingdom (Figure 4.21). Finally, the share of people who are sceptical the political system lets people like them have a say in what government does increased on average by three percentage points in the past two years, and more so in Estonia, Iceland and Korea (Figure 4.22).

Figure 4.20. Slightly fewer people think the government would change a national policy if people are against it in 2023 compared to 2021

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government would change a national policy if over half of the people expressed a view against it, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If over half of the people in [COUNTRY] clearly expressed a view against a national policy, how likely do you think it is that it would be changed?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Mexico: ‘’If more than half of the people in the country complained about a national policy (education, taxes, security, etc.), how likely is it that the authorities would change it?’’. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

Figure 4.21. On average, people’s confidence that government would adopt opinions gathered in public consultation slightly decreased between 2021 and 2023

Share of population who find it likely or unlikely that government would adopt opinions gathered in public consultation, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “If you participated in a public consultation on reforming a policy area, how likely do you think it is that the government would adopt the opinions expressed in the consultation?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Mexico: ‘’If a public consultation were to be held to lower or raise taxes, how likely is it that your opinion would be taken into account?’’. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

Figure 4.22. On average, the share of people who are sceptical the political system lets people like them have a say in what government does increased between 2021 and 2023

Share of population reporting different levels of perceived likelihood that the political system allows people to have a say in what the government does, 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “How much would you say the political system in [COUNTRY] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?”. The survey question in 2021 followed a slightly different wording in Norway: ‘’To what extent would you say that the Norwegian political system allows people such as yourself to exercise political influence?’’. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

4.6. Conclusion for policy action to enhance trust

On complex policy issues, the results of the Trust Survey show different steps that can be taken to enhance trust in public institutions.

Emergency readiness, while less impactful on trust levels than during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, remains an important driver of trust in national and local governments and civil service. Governments must continue improving their reliability and preparedness for future crises.

Strengthening confidence in government’s ability to address complex policy challenges, including those with global ramifications, is a priority. On average 41% are confident that the government would regulate AI appropriately and 42% that the country would succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In terms of challenges that require long-term thinking and the fair balancing of different interests, both national governments and national parliaments can consider whether questions of intra-national and inter-generational fairness are allocated sufficient space not only during the policy deliberation process, but also in terms of how government and members of parliament communicate.

The ability of parliament to hold government accountable is an important driver of trust in parliament and in government. Strengthening the oversight function of parliament along with other inherent checks and balances in the political system in general is likely to be a key ingredient to help maintain support for representative democracy. While not included in the 2023 survey, results from the 2021 survey showed that judicial independence was likewise a driver of trust in the national government and in the judicial system.

A majority doubts that decision-making is carried out in the public interest. On average only three out of ten find it likely that the government would withstand undue influence from corporations. In a democracy, engaging diverse interest groups when designing policies, should only be viewed as a means to enhance the quality of a policy measure, and not as democratic engagement. In parallel, citizens’ consultations, which is democratic engagement, needs to be enhanced and made more meaningful in terms of its consequences on decisions. Along with stronger integrity and transparency standards (OECD, 2024[7]), this is a very important development to ensure policies are seen as designed for the public's benefit, rather than private interests.

In representative democracies, elections remain the primary method for incorporating different views into decision-making. However, the public's keen interest in direct democracy, along with perceived limited ability to participate in political processes, suggests a desire for more impactful ways to interact with and influence policy-making processes. Governments are now urged to improve civic participation, focusing on institutionalising direct and deliberative participation mechanisms. However, the challenges of collecting input from the population through a wider variety of channels, and the fact that fewer than one in three believe the government would adopt opinions expressed in public consultations, underline the need for clear expectations about the role of deliberative and direct democracy within the representative democracy system.

In addition to promoting these additional "points of engagement" between governments and the public, governments can empower people to participate in public debate and impact political processes by fostering a legal, political, and social environment that enables a vibrant civic space.

References

[12] Fishkin, J. and P. Laslett (2008), Debating Deliberative Democracy, Wiley Blackwell, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470690734.

[11] International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (2008), Direct Democracy The International IDEA Handbook.

[7] OECD (2024), Anti-Corruption and Integrity Outlook 2024, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/968587cd-en.

[6] OECD (2023), Government at a Glance 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d5c5d31-en.

[1] OECD (2023), Report on the implementation of the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[8] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[9] OECD (2022), OECD Guidelines for Citizen Participation Processes, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f765caf6-en.

[2] OECD (Forthcoming), Updated Guidelines on Measuring Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing.

[4] OECD/The World Bank (2019), Fiscal Resilience to Natural Disasters: Lessons from Country Experiences, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/27a4198a-en.

[10] Schiller, T. (2024), “Direct democracy”, in Encyclopedia Britannica.

[3] UNDP (2022), “2022 Special Report on Human Security”, https://hs.hdr.undp.org/.

[5] UNEP (2022), Emissions Gap Report 2022, https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

Note

← 1. Estimates suggest that in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, global greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced to 33 gigatons of CO2 equivalent by 2030, and to 8 gigatons by 2050. But global emissions are projected to reach 58 gigatons by 2030.