People’s demographic background, socio-economic characteristics and their political attitudes affect their perceptions of and trust in government. This chapter outlines the varying levels of, trust in government, and other public institutions among different population groups. These groups are defined by their socio-economic and demographic characteristics, such as age, degree of financial security, educational background and gender, and by their political attitudes comprising political partisanship, political voice and ability to participate in politics. It also demonstrates how the trust gaps between these groups have evolved in the countries with data available for 2021 and 2023; with a specific focus on the evolution of the gender trust gap.

OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results

2. Socio-economic conditions, political agency and trust

Abstract

A significant challenge in representative democracies is governing a pluralistic society made up of diverse socio-economic backgrounds and political attitudes. Governments often struggle to balance and engage with the varied needs, interests, and views of their population. For example, the most vulnerable groups are typically less engaged in the democratic system, indicating an area that needs improvement in OECD countries. Viewing trust in public institutions through the lens of these different population groups can help shed light on how effectively governments are managing the challenge of inclusive and fair policy making.

This chapter focuses on the differences in the share of people with high or moderately high trust across population groups, defined either by their socio-economic and demographic characteristics, their partisanship, or their political agency, including people’s confidence in their political voice and their ability to participate in politics. We define these differences in trust levels by population groups as 'trust gaps'.

2.1. Levels of public trust vary more based on one’s sense of political agency and partisanship than socio-economic or demographic characteristics

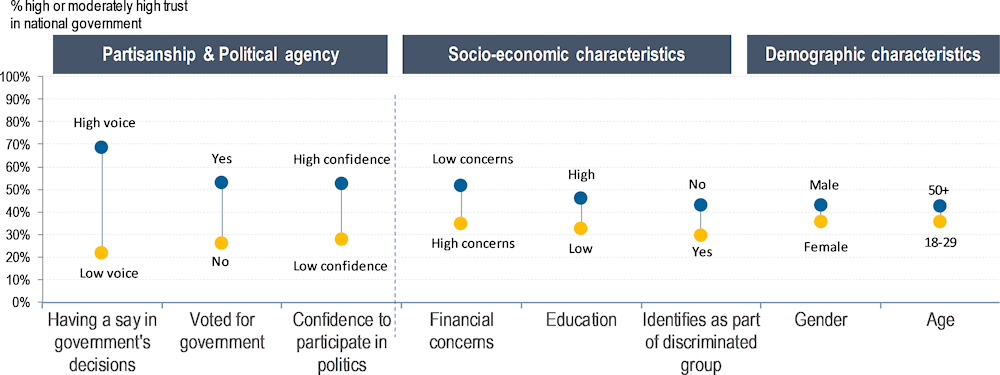

Across OECD member countries, trust in public institutions varies more depending on individuals’ sense of political agency and partisanship than on their socio-economic and demographic characteristics. This underscores the well-established link between political trust and the feeling of having a say in policy decision making (OECD, 2022[1]). The sense of having an influence on political processes and, to a lesser degree, the confidence to participate in politics, the combination of which constitutes “political agency”, are crucial in explaining variations in trust towards the national government. Moreover, partisanship, measured by whether an individual voted for the incumbent government in the last election, also plays a significant role. Comparing the size of trust gaps shows that trust levels, on average, differ less among socio-economic groups and demographics, like education, gender, and age, compared to variations based on feelings of political agency and partisanship (Figure 2.1).1 This trend, showing larger variations in trust levels by feelings of political agency and partisanship, holds true in all countries.

Figure 2.1. Political agency tends to play a more significant role in people's trust in the national government than their socio-economic status or demographic characteristics

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by level of respondents’ socio-economic and demographic characteristics, partisanship and political agency, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted averages across OECD countries of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” by respondents’ feelings of political agency, partisanship, socio-economic background and demographic characteristics. Shown here is the proportion that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by respondents’ feeling of political agency (feeling confident to have a say in what the government does, feeling confident to participate in politics) and partisanship (voted for government during last national elections), socio-economic background (financial concerns, education, identification as part of a discriminated group) and demographic characteristics (gender, age). Financial concerns are measured by asking ‘’In general, thinking about the next year or two, how concerned are you about your household's finances and overall social and economic well-being?’’ and aggregating responses 3 (somewhat concerned) and 4 (very concerned). Low education is defined as below lower secondary educational attainment and high education as tertiary education, following the ISCED 2011 classification. People’s identification of a discriminated group is measured by responses ‘’Yes’’ to the question “Would you describe yourself as being a member of a group that is discriminated against in [Country]?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Equal opportunities for representation in policy processes and policy making is a crucial aspect of a functioning democracy. Feelings of lack of political voice are associated with low trust in national government. On average, among those who report they have a say in what the government does, 69% report high or moderately high trust in the national government, in contrast to only 22% among those who feel they do not have a say, representing the largest trust gap (Figure 2.1). This is a worrisome result considering that on average, 53% responded that they had no say in what government does (Figure 4.15 in Chapter 4).

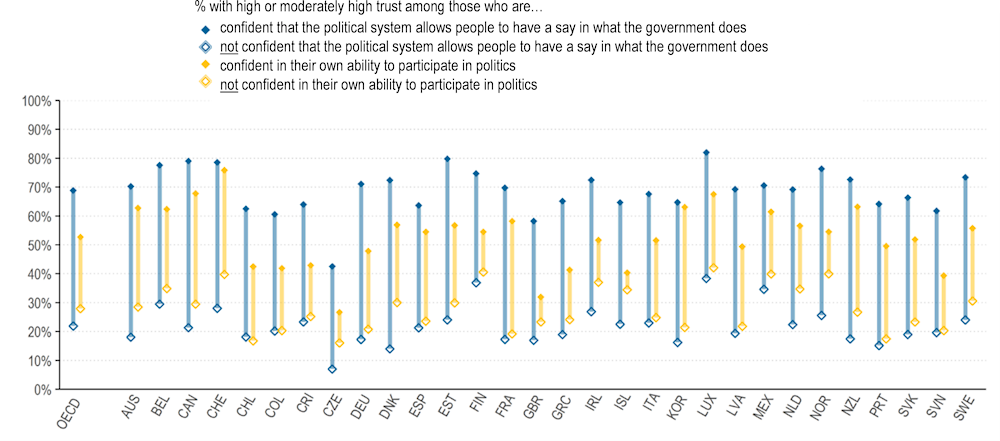

Further, people’s trust in national government is also positively related to confidence in one’s ability to participate in politics. On average across countries, there is a 25-percentage point trust gap between those who are confident in their ability to participate in politics and those who are not. While in eight countries the gap is larger than 30 percentage points, in Czechia, Iceland and the United Kingdom, differences in trust levels based on people’s confidence in their ability to participate are much smaller (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. People who feel they have a say in what the government does or are confident to participate in politics also express higher trust in the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by feeling they have a say in what the government does (blue) and confident to participate in politics (yellow), 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” by respondents’ feeling of having a say (blue) and confidence to participate in politics (yellow). Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust’’ based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by whether people feel they have a say (blue): ‘’How much would you say the political system in [COUNTRY] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?’’ and feel confident to be able to participate in politics (yellow): ‘’How confident are you in your own ability to participate in politics?’’. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Aspects of political agency, such as political voice and confidence in one's ability to engage in politics, are partially linked to people's socio-economic and demographic backgrounds. For instance, people with higher education and financial security are more likely to believe they can participate in policy making than people with lower education and financial security. The gaps are 20 and 10 percentage points, respectively, indicating simultaneously a reason for and an outcome of unequal participation in political processes and decision making. However, while self-reported belonging to a discriminated group is an important factor for people’s level of trust in the government, it does not significantly impact people’s confidence in their own ability to participate in politics. A possible reason for this seemingly incongruous result can be found in prior research, which suggests that feelings of discrimination may increase political engagement (Reher, 2018[2]), thereby boosting individuals' confidence in their own ability to participate in political processes. Politically more aware individuals may also be more likely to self-identify as belonging to a group that is discriminated against.

Similarly, the Trust Survey finds that a large share of those who have no trust in the national government and that feel they lack a political voice still feel confident in being able to participate in politics and indeed have engaged in various political activities (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Distrusting but not disengaged

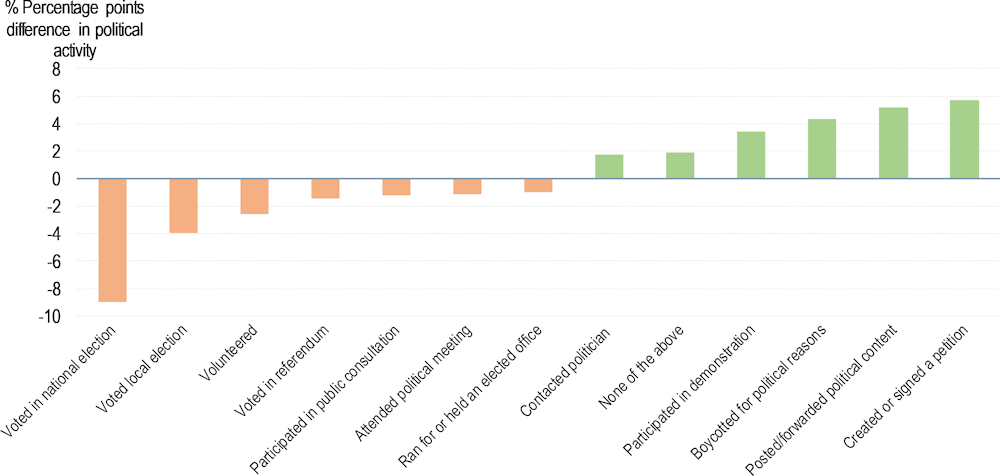

Individuals who report no trust in their government - or distrusting individuals - are often portrayed as politically disengaged or disenchanted with politics and democracy more generally. However, Trust Survey data from the 2021 wave suggested that while part of that group is indeed disengaged, a significant share engages politically in various ways, but feels they lack political voice (Prats, Smid and Ferrin, 2024, forthcoming[3]).

The 2023 Trust Survey finds that 15% of people express a lack of trust in their national government, by answering ‘0’ on the 0-10 response scale. Despite this being a relevant share of respondents who lack trust, this share decreased since the 2021 Trust Survey (Figure 1.4). Regarding the feeling of political agency, among individuals lacking trust in the government, approximately one-third (31%) feel confident in their ability to participate in politics, whereas merely 7% feel they have a voice in what the government does.

In terms of people’s political engagement, those who do not trust the national government reports to have voted less in the last national election than the rest of the population - 75% compared to 84%. At the same time, a large majority (86%) of those who reported a lack of trust in their national government were politically engaged in one form or the other and to a larger extent than people who reported higher levels of trust in government (Figure 2.3). On average, a significantly higher share of those who reported no trust in government, compared to the rest of the population, were engaged in unconventional political activities, such as posting or forwarding political content (5 percentage points higher) and boycotting products for political reasons (4 percentage points higher). They also more frequently signed a petition (6 percentage points higher) and participated in demonstrations (3 percentage points higher).

Figure 2.3. Distrusting respondents are politically engaged

Percentage points difference in participation in political activities in the previous year between people who stated a lack of trust (=0) compared to people exhibiting higher trust (1-10) in the national government, 2023

Note: The figure presents the OECD distributions of responses to the question ‘’Over the last 12 months, have you done any of the following activities?”. Shown here is the difference in the proportion of people who have participated in any of the activities among those who report no trust in the national government (response ‘’0’’) and those who reported higher trust in the national government (responses 1-10).

How to read: On the left end of the figure, a negative value indicates that this form of political participation is less prevalent among the distrusting group (who answered 0 on the response scale) across OECD countries, compared to those who indicated trust levels of 1-10. On the right end of the figure, a positive value indicates that this form of political participation is more prevalent among the distrusting group across OECD countries. For example, distrusting respondents were 5 percentage points more likely to state that they posted or forwarded political content during the last 12 months compared to the rest of the population.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

The effects of political polarisation on the functioning of democratic governments have been discussed at length in recent years. Political polarisation has been associated with higher levels of political disenchantment from democratic processes, resulting in diminished democratic resilience of political systems (Iyengar et al., 2019[4]). Additionally, when polarisation embeds itself in political structure, narrowing the number of “common ground” issues, this strongly hinders governments' ability to enact reforms and implement essential policies within democratic systems. Partisanship effects have been described as a ‘’political gridlock’’ and barrier for passing structural reforms in OECD countries (Brock and Mallinson, 2023[5]). Additionally, in some contexts, partisanship has significantly affected people’s adherence to COVID-19 policies and restrictions, including people’s willingness to be vaccinated (Impact Canada, 2023[6]), demonstrating the influence of political alignment on policy compliance (Druckman et al., 2020[7]).

Other than asking about political support for the current government in the last national election, the Trust Survey does not include any questions on the political orientation and attitudes towards other political parties. The proxy used to measure the extent of polarisation is the gap in trust in the national civil service between individuals who (would) have voted for the current government or those who did not. The reason for using this gap as a measure of polarisation is that trust in administrative, as opposed to political, institutions should, in principle, depend on how well these perform on public governance dimensions, rather than on partisan support. The existence of a trust gap in administrative institutions between supporters and opponents of the current government suggests that partisanship is becoming political polarisation.

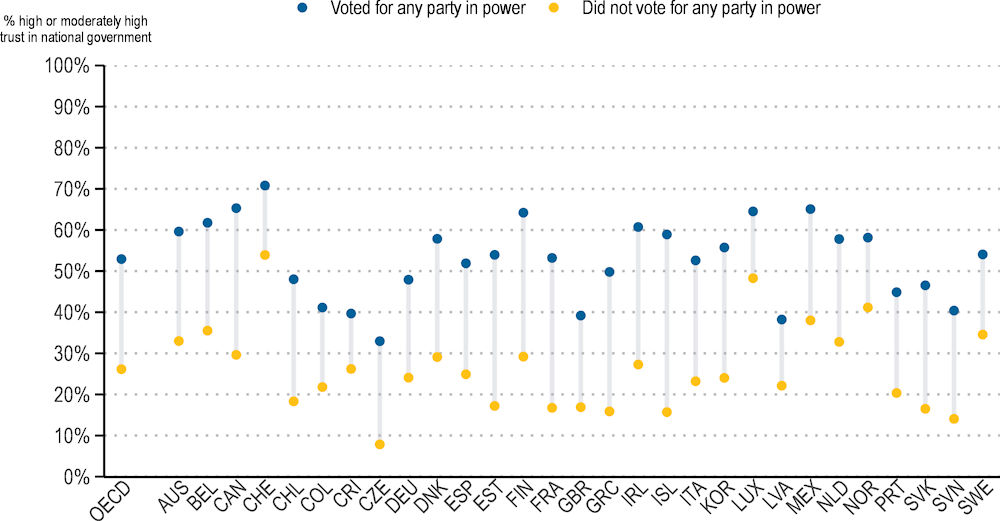

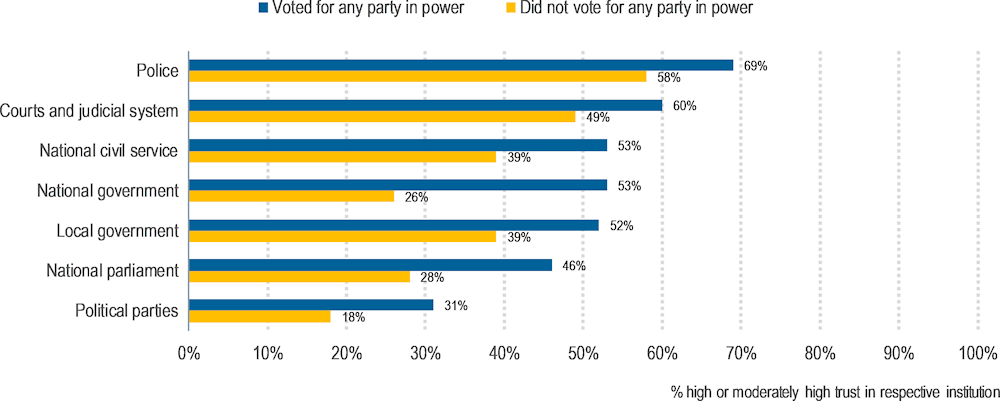

Unsurprisingly, in all OECD countries, trust in the national government is higher among individuals who voted for a party currently in power in the most recent national election: on average among those who voted for the government, a majority reports high or moderately high trust in the national government (53%), compared to only 26% among those who supported the opposition. The gap is notably large in Canada, Estonia, Finland, France and Iceland (Figure 2.4). This 27-percentage point “partisanship gap” in trust in national government cannot be considered as a sign of polarisation. However, levels of trust in other, more “administrative”, facets of government such as the police, courts and the judicial system, and the national civil service, which should be shielded from partisanship, still have a partisan trust gap of 11-13 percentage points (Figure 2.5). For example, in Belgium, Canada, Estonia and Greece, the partisan trust gap in the national civil service exceeded 20 percentage points. Moreover, polarisation – measured by the trust gap in the (national) civil service between those who voted for the government and those who did not – has increased by 3 percentage points on average between 2021 and 2023.2

Figure 2.4. People who voted for a party in power are more trusting of the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by whether they voted for a party in power or not, 2023

Note: The figure presents the responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government’’ by respondents’ political alignment. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust’’ based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by whether people voted (or would have) voted for the government in power: ‘’Is the party you voted for in the last national election on [DATE] currently part of the government?’’. New Zealand is excluded from the figure as the survey question on voting for the current government was not included there. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Figure 2.5. Trust in all public institutions is lower for people who did not vote for a party in power

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in different public institutions by whether people voted for the government or not, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted averages across OECD countries of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [institution]’’ by respondents’ political alignment. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust’’ based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by whether people voted (or would have) voted for the government in power: ‘’Is the party you voted for in the last national election on [DATE] currently part of the government?’’. New Zealand is excluded from the OECD average as the survey question on voting for the current government was not included there.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

2.2. The socio-economically vulnerable tend to have less trust in public institutions, with a growing divide based on education levels

Economic vulnerability is associated with low levels of trust in the national government. On average across the OECD, 46% of individuals in the high-income group have high or moderately high trust, compared to 41% in the middle and 31% in the low-income group.

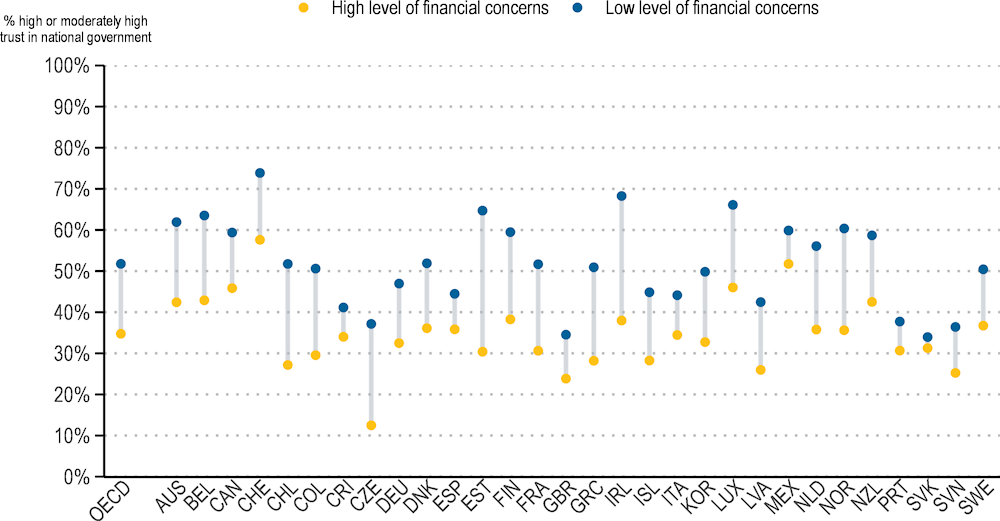

In all countries, feelings of economic insecurity are associated with lower trust in the government, and in many countries, self-reported personal financial vulnerability has a greater association with lower trust in public institutions than people’s actual income levels.3 On average across OECD countries, just 35% of those concerned about their economic and financial future report having a high or moderately high level of trust in their national government (Figure 2.6). Conversely, among those with fewer economic worries, the share of respondents reporting high or moderately high trust level is 17 percentage points greater (52%).

Figure 2.6. In all countries, feelings of economic insecurity correspond to lower trust in the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by financial concerns, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by whether respondents mentioned 3 (somewhat concerned) and 4 (very concerned) to the question ‘’In general, thinking about the next year or two, how concerned are you about your household’s finances and overall economic well-being?’’. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

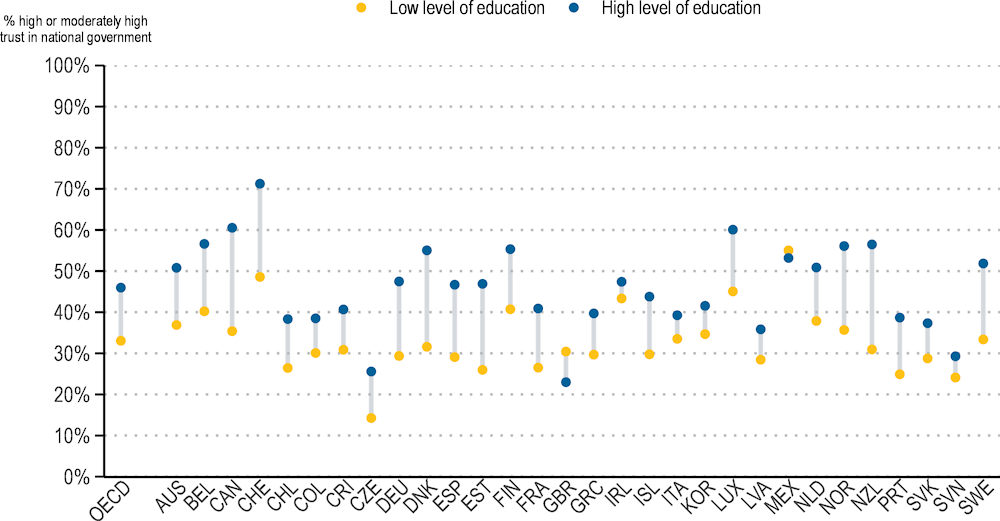

Having a university degree is associated with 13 percentage points higher trust in government on average across countries compared to those who did not complete studies beyond lower secondary education. However, in the United Kingdom and to a lesser extent Mexico, people with higher levels of education tend to have lower levels of high or moderately high trust in their national government than people with lower levels of education (Figure 2.7).

On average across 18 countries with available data, the education gap in trust in government increased by 4 percentage points since the 2021 Trust Survey, which contrasts with a stagnating trust gap between people with different levels of economic and financial concerns. Lower educated people tend to trust the government less in 2023 than in 2021: the share of lower educated people with high or moderately high trust in the national government was 34% in 2023, down from 39% in 2021.4 Among the highly educated, trust also declined, but only by two percentage points. Moreover, the gap between lower and higher educated people has increased in all perceptions of public governance drivers between 2021 and 2023, and particularly so for perceptions related to government openness, such as voicing views on local government decisions and adoption of views expressed in public consultations. While 39% of lower educated people felt it was likely that they could voice their views in local government decisions in 2021, compared to 47% of higher educated people, the respective shares have become 34% and 47% in 2023.

Figure 2.7. Individuals with higher levels of education tend to have more trust in the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by respondents’ education, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by respondents’ highest education level attained: higher education (tertiary education) or lower education (lower secondary education and below). The lower education group in Chile, Colombia and Greece combines lower and medium education attainment (upper secondary and post-secondary education) due to an underrepresentation of the lower education group in the survey sample in those countries. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

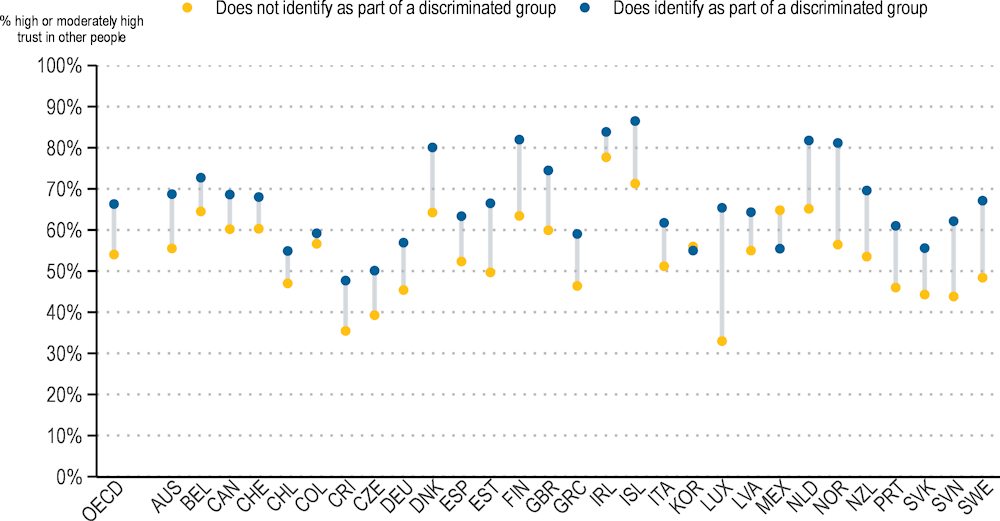

Feelings of discrimination reinforce the social and political vulnerability of certain groups in society. Identifying as belonging to a discriminated-against group is tied to both lower trust in public institutions and in other people. Indeed, the interpersonal trust gap is as large as the government trust gap. On average across the OECD, the interpersonal trust gap between those who self-identify as belonging to a discriminated group and those who do not is 12 percentage points, while the government trust gap is 14 percentage points (Figure 2.8). A similar gap is also visible for trust in other public institutions, especially trust in the police and trust in courts and the judicial system, as well as people’s (dis)satisfaction with services. However, as previously noted, unlike for other socio-economic factors, self-identification of belonging to a discriminated against group is not related to a drastically different feeling of being able to participate in politics.

Figure 2.8. Trust in other people and feelings of discrimination appear to be intertwined

Share of respondents with high or moderately high trust in other people by feeling of belonging to a discriminated group, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust most people?” by respondents’ perceptions of belonging to a discriminated group. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by whether respondents stated whether they feel they belong to a discriminated group: ‘’Would you describe yourself as being a member of a group that is discriminated against in [COUNTRY]?’’. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Levels of trust in other people also show significant variations across various socio-economic and demographic groups. For example, people with a low level of education have 12 percentage points less trust in other people, compared to those with a high level of education. This interpersonal trust gap by levels of education is again nearly as large as the government trust gap of 13 percentage points. This disparity extends across economic status and age groups, though the relative sizes of the interpersonal and government trust gaps between groups defined by these characteristics are not nearly identical as they are for education and self-identified discrimination. The pattern of similar interpersonal and government trust gaps suggests reinforcing mechanisms might be at play in how socio-economic and demographic backgrounds affect trust in government and trust in other people. This underscores the often compounded and intersectional nature of vulnerability.

2.3. Women and younger people continue to place less trust in government, but the gender trust gap has increased while the age trust gap has narrowed

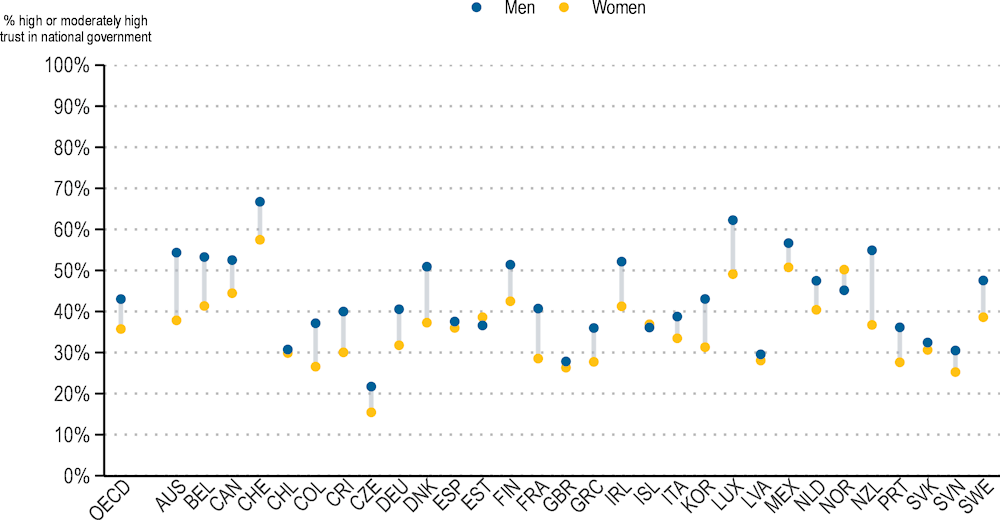

In most countries, women tend to trust the government less than men. In 2023, 36% of women have high or moderately high trust in the government, compared to 43% of men. The gap is larger in countries such as Australia,5 Denmark, France, Luxembourg, and New Zealand, and smaller in Chile, Latvia, the Slovak Republic, Spain and the United Kingdom. Only in Estonia, Iceland and Norway, women tend to trust the national government slightly more than men do (Figure 2.9).

On average, the gender trust gap (Box 2.2) has seen a fourfold increase since the 2021 Trust Survey, from 2 percentage points in 2021 to 8 percentage points in 2023, notably among youth; a trend worth monitoring going forward. This contrasts with decreasing trust gaps between the youngest (18‑29) and oldest (50+) population group.

Figure 2.9. The gender trust gap varies significantly across countries

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by gender, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” by respondents’ gender. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by respondents’ self-identified genders. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Box 2.2. Gender gaps in trust

Since 2021, gender trust gaps in public institutions have become more pronounced together with the education trust gap in the national government. These gender and education based differences have increased more than age trust gaps, which have declined since 2021. For the eighteen countries that participated in the 2021 and 2023 waves, the share of women with high or moderately high trust in the national government in 2023 trails the share of men by eight percentage points, compared to a 2 percentage point gap in 2021. The growing difference between women’s and men’s level of trust in the national government is noteworthy in Finland and Sweden. Similar increases in gender gaps are observed for trust in the national civil service (5 percentage points), parliament and local government (4 percentage points respectively), whereas the gender trust gap in other public institutions has remained narrow over the past two years. Others are similarly discussing the increasingly divergent political attitudes between women and men (Financial Times, 2024[8]). Three aspects may help shed a light on the rapid increase of the gender trust gap in some countries.

First, the growth of the gender trust gap between young women and men (those aged 18-29) is twice as large as between women and men aged 50 years and older. In the younger age group, the average gender trust gap has increased by 8 percentage points in the past two years, (from three to eleven percentage points) across the countries that participated in both survey rounds. In the case of Canada, Ireland and Korea, the gender trust gap among young men and women has increased more than in other countries and notably more than among the entire population1.

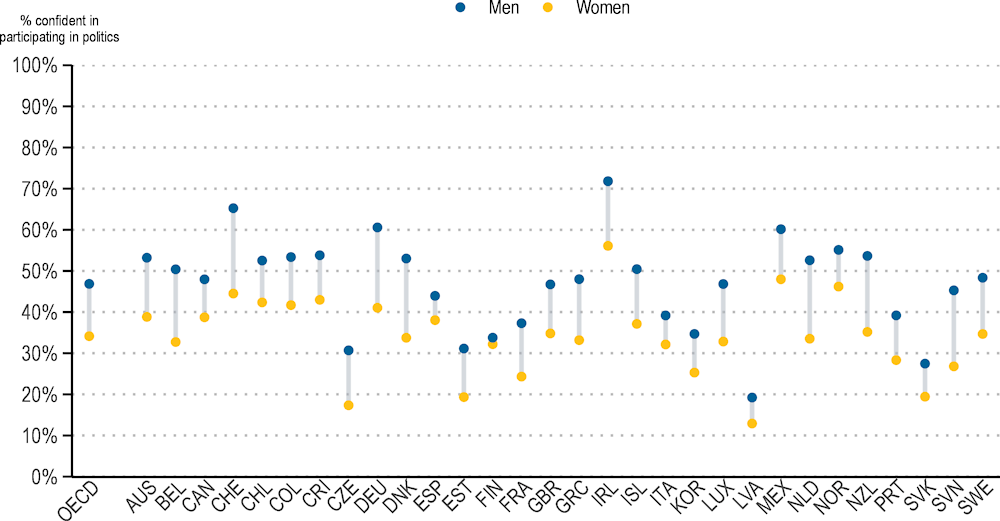

Second, overall, at any age, male respondents were more likely to support a party in power, feel confident in their ability to participate in politics, and believe they have a political voice. These discrepancies contribute to the gender trust gap, as people with higher political agency tend to have higher trust in government. Across OECD countries, for example, men were 13 percentage point more likely than women to feel confident in their ability to participate in politics, a trend that holds across all countries (Figure 2.10).

Finally, on average the gender gap has increased for perceptions of all the public governance drivers between 2021 and 2023. In particular, women have become more sceptical about government’s capacity to tackle complex issues and to ensure fairness in public services.

Figure 2.10. Men are more likely than women to feel confident in their own ability to participate in politics

Share of population who feel confident in their own ability to participate in politics by gender, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question ”How confident are you in your own ability to participate in politics?” by respondents’ gender. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that are “confident” in the 2023 Trust Survey based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by respondents’ self-identified genders. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

1. These findings should be interpreted with caution as the country data reflects the national distribution by age and by gender but not the intersection of these two characteristics. For example, the share of under-30 year old men (or women) included in the sample does not necessarily correspond to the share of under-30 year old men (or women) in the population.

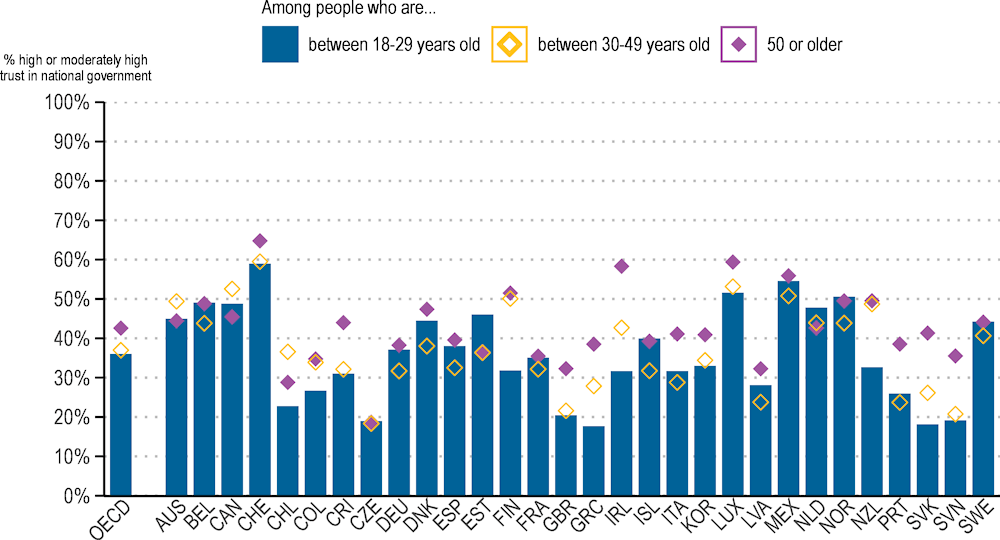

Young people tend to trust the national government less compared to older generations. More specifically, 43% of people aged 50 and above report having high or moderately high trust in the national government, compared to 36% among people aged 18-29. Similar to the younger cohort, 37% of people aged 30-49 have high or moderately high trust (Figure 2.11). In a few countries, such as Canada, Estonia and the Netherlands, the younger age group is more trusting in the national government than the older age group; and in a few others, such as Australia, Belgium, Czechia, Norway and Sweden, there are no differences.

Figure 2.11. People over 50 find the government more trustworthy

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government by age, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?” by respondents’ age. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that have “high or moderately high trust” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by three age groups: 1) 18-29;. 2) 30-49; 3) 50 and above. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

On average across 18 OECD countries where data are available, the age gap in trust in the national government halved between 2021 and 2023 (from 10 to 5 percentage points). This decline in the size of the trust gap was simultaneously due to a slight increase of trust among the younger population (39% of people aged 18-29 reported high or moderately high trust in the national government in 2023, compared to 37% in 2021), and a decrease of trust among people aged 50+ (which dropped from 47% to 43%). A rising share among young people who feel they have a say in the political system (from 33% to 35%) and a declining share among older people (from 29% to 26%) may contribute to this trend.

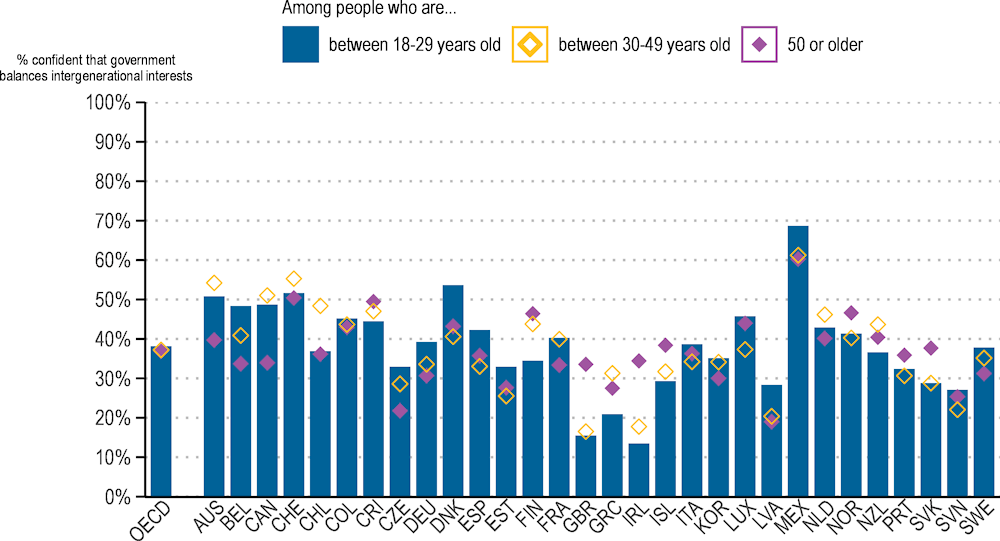

The fact that younger respondents are on average still slightly less trusting in the government raises the question whether certain public governance drivers may be more age sensitive than others. However, on average across countries, views that government can adequately balance intergenerational interest, address adequately the green and digital transitions, or respond to emergencies do not differ significantly between younger and older populations. In the majority of surveyed countries, younger people on average display a higher degree of confidence in the government’s ability to serve intergenerational interests, especially so in Belgium and Canada. On the contrary, in Ireland and the United Kingdom, younger people are significantly less confident than older people in the government’s ability and willingness to balance interests across generations. Lastly, countries like Chile, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Switzerland display little to no difference between age groups on this issue, indicating a more uniform belief in the government's handling of intergenerational interests across the population (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. In some countries, young people are more confident than older people in government’s ability to balance intergenerational interests, and in other countries the opposite is true

Share of population who feel confident that the government balances the interests of current and future generations by age, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that the national government adequately balances the interests of current and future generations?” by respondents’ age. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that are “confident’’ based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the 0-10 response scale, grouped by three age groups: 1) 18-29;. 2) 30-49; 3) 50 and above. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

2.4. Conclusion for policy action to enhance trust

To reduce trust gaps between population groups, public institutions can take the following steps.

Individuals' sense of political agency and partisanship matter more for trust in government than their socio-economic or demographic characteristics. People who feel they have a say in what the government does are, on average, more than three times as likely to say that they trust the government than people who feel they don’t have a say. This highlights the significance of political agency and participation in shaping trust outcomes, suggesting a need for policies that promote political inclusivity and engagement to boost trust in public institutions.

A sizeable minority of 15%, albeit lower than in 2021 in the countries with available information for both years, indicated that they had no trust at all in the national government. This group tends to vote less in national and local elections and feels more disempowered regarding what the government does. At the same time, a large majority of those who report a lack of trust in government were engaged in political activities, with an overrepresentation in unconventional forms, such as posting political content and boycotting products, but also signing petitions and participating in demonstrations.

Policies designed to mitigate economic vulnerability and discrimination could be key to closing the trust gap and fostering widespread trust in public institutions, as these factors greatly influence individuals' trust levels. Trust is considerably lower among people worried about their personal financial circumstances: only 35% of the group reporting financial worries trust the government, compared to 52% among people with fewer financial worries.

Women and younger people tend to have lower trust in government than men and older individuals (50+). Particular attention should be given to the rapidly widening gender trust gap, also among younger women. In 2023 the share of women reporting trust in the government trails the share of men by 8 percentage points, compared to a 2 percentage point gap in 2021, on average among 18 countries. Additionally, at any age, women were less likely to feel confident in their ability to participate in politics, and believed they have a political voice. This indicates that governments should enhance their efforts to engage these groups and address their unique concerns to ensure equal access and representation in policy making.

References

[5] Brock, C. and D. Mallinson (2023), “Measuring the stasis: Punctuated equilibrium theory and partisan polarization”, Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 52/1, pp. 31-46, https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12519.

[7] Druckman, J. et al. (2020), “Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 5/1, pp. 28-38, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5.

[8] Financial Times (2024), A new global gender divide is emerging, https://www.ft.com/content/29fd9b5c-2f35-41bf-9d4c-994db4e12998.

[6] Impact Canada (2023), Why Trust Matters: TIDES Program.

[4] Iyengar, S. et al. (2019), “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States”, Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 22/1, pp. 129-146, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.

[1] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[3] Prats, M., S. Smid and M. Ferrin (2024, forthcoming), “Lack of Trust in Institutions and Political Engagement: An analysis based on the 2021 OECD Trust Survey”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance.

[2] Reher, S. (2018), “Mind This Gap, Too: Political Orientations of People with Disabilities in Europe”, Political Behavior, Vol. 42/3, pp. 791-818, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-09520-x.

Notes

← 1. These results generally hold true in regression analyses in which trust in the national government is the dependent variable (see Annex A), though trust differences are less stark by perceptions of political agency than in the descriptive analysis shown in this chapter. In a regression analysis of the 2023 data, having voted for the current government is associated with the highest average marginal effect on the likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in the national government, followed by having higher (compared to low) educational attainment, being aged 50 or above (compared to being aged 18 to 29), having an intermediate level of education and having a say in what government does.

← 2. The 2021 survey question referred to ’trust in the civil service’, while in 2023, it referred to ’trust in the national civil service’. A separate survey question referred to trust in the regional/local civil service, as appropriate in each surveyed country.

← 3. Objective income levels are measured grouping respondents in the bottom 20%, middle 60% and top 20% of the country-level household income distribution.

← 4. In the case of Chile, Colombia and Greece lower and medium education levels are combined due to the underrepresentation of lower-educated respondents in those countries.

← 5. The Trust and Satisfaction in Australian Democracy survey found a trust gap between men and women of 11 percentage points for the June and 9 percentage points for the November wave. Methodological differences, including a different response scale and a sampling methodology relying on different quotas, can contribute to differences in the measured trust gap.