Given that multiple factors influence public trust in government, it is interesting to explore their relationship with trust levels simultaneously. This is achieved through econometric analysis, which examines the links between the outcome of interest – trust in a public institution – with the public governance drivers of trust and individual background characteristics. This chapter takes a holistic perspective: The public governance drivers are seen from a birds-eye view, stripped of their details, but in turn considered jointly with others. This allows to consider how positive perceptions of a given driver are related to the probability of placing high or moderately high trust in a public institution when holding other perceptions as well as background characteristics constant. Findings from the econometric analysis can be particularly useful for identifying areas in which improvements could lead to boosts of trust levels.

OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results

Annex A. The public governance drivers and personal characteristics shaping trust in public institutions

Understanding how multiple public governance drivers affect trust

The results of the econometric analysis show how much more likely an individual is to have high or moderately high trust in a given public institution if they have a positive perception of the respective public governance driver, holding their assessment of the other drivers and their socio-economic and political background constant. The analysis therefore provides insights into how changed perceptions of a given driver can affect trust levels. Box A.1 provides more details on the analytical method.

Nevertheless, the analysis has limits in terms of being able to assess whether the driver causes trust to rise. First, trust in an institution can make the institution function more effectively, indicating the possibility of reverse causality. Second, people’s perceptions of different public governance drivers may not only move in parallel, leading to collinearity, but may also have a joint impact on trust. Third, factors that are not measured by the Trust Survey can also have an influence of trust, contributing to omitted variable bias.

Despite these and other methodological difficulties, the econometric analysis is a useful tool to understanding which public governance drivers have the strongest association with trust, even when accounting for other variables that are known to affect trust. Results from this analysis provide governments with a compass to guide them on which dimensions to leverage or improve upon to enhance trust.

The following sub-sections show the results of logistic regression analysis of trust in the national government, national civil service, national parliament and local government on the explanatory and control variables. Each figure shows all the variables that a have statistically significant relationship with trust in the respective institutions, with a higher relevance (moving from left to right along the x-axis) indicating a larger estimated association with trust. The position along the y-axis shows the unweighted average share of respondents who rated the respective variable positively (percentage of “6-10” responses on a 0-10 scale).

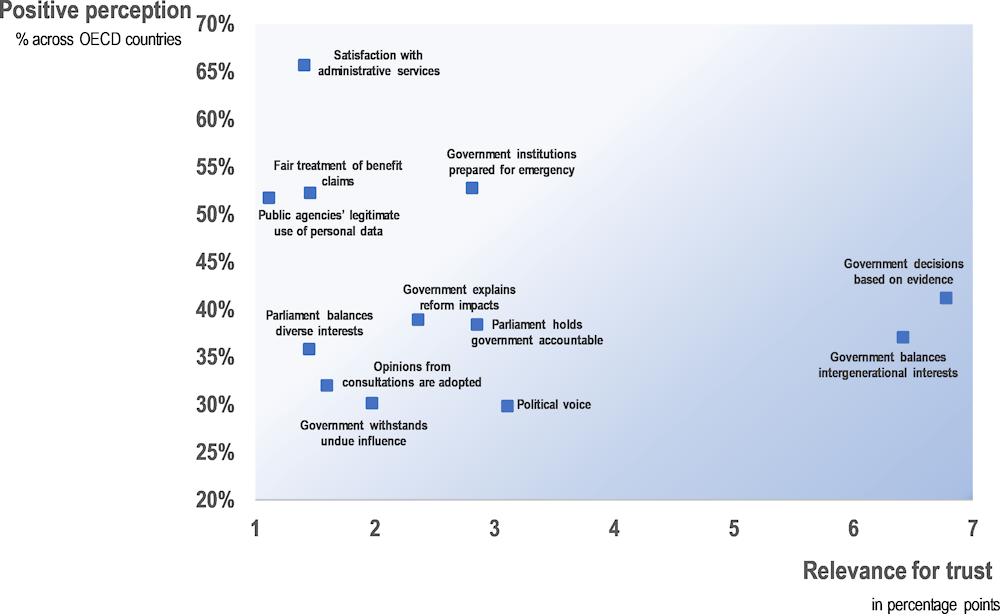

Responsiveness to evidence, balancing intergenerational needs and ensuring political voice are highly associated with trust in the national government

Increasing positive perception of government’s capacity to use the best available evidence in decision-making and to adequately balance the interests of current and future generations are likely to have the highest influence on trust in the national government. Individuals who are confident on these two aspects are 6.8 and 6.4 percentage points, respectively, more likely to have high or moderately high trust in national government. Ensuring that people feel they have a say in what government does is associated with an increase in trust of 3.1 percentage points (Figure A.1).

The average positive perception of these three main drivers of trust in the national government is quite different: while 41% believe that the government would use best available evidence in decision-making, 37% expect a fair balancing of intergenerational interests, and only 30% feel they have political voice (Figure A.1).

It is also important to note that even among those who have not voted for the current government, evidence-based decision making, balancing the interests of current and future generations and ensuring that people feel they have a political voice remain the most important drivers of trust in the national government.

Along with the very strong association of these two variables with trust, other governance variables also have a meaningful relationship with trust. Among these are the already positively perceived reliability dimension of being ready for future emergencies, which is associated with an increased likelihood of trust of 2.8 percentage points and the integrity-enhancing ability of the national parliament to hold the national government accountable, a positive perception of which can raise trust by 2.8 percentage points. Several other public governance drivers mostly related to complex policy issues, such as government withstanding undue influence, adopting opinions raised in public consultations, balancing interests of different groups in society, and explaining the impact of reform also have a significant relationship with trust in the national government; alongside with few public governance drivers related to the day-to-day interaction between citizens and government, such as treating service application fairly, using personal data only for legitimate purposes and ensuring satisfaction with administrative services.

Figure A.1. People who perceive government to use the best available evidence and balance intergenerational interests are more likely to have high or moderately high trust in the national government

Percentage point change in high or moderately high trust in national government in response to a more positive perception of the public governance variables (X-axis) and the unweighted OECD average share of the population with a positive perception of the noted variables (Y-axis)

Note: The figure shows the statistically significant determinants of trust in the national government in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, including whether they voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at the p<0.01 level.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

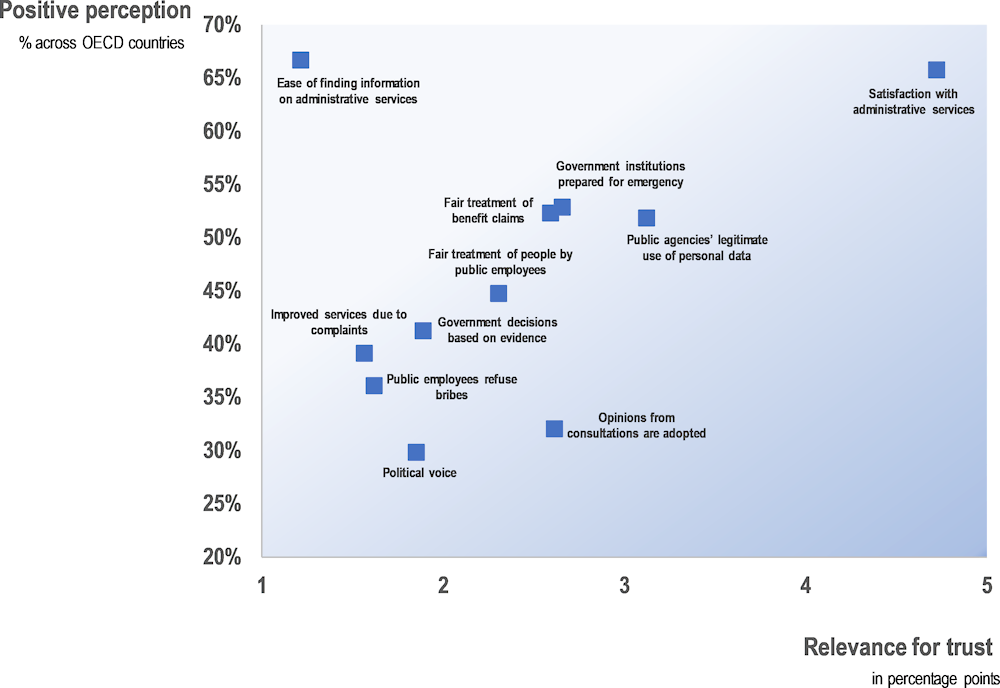

Perceived reliability, fairness and openness are associated with higher trust in the national civil service

Several of the public governance drivers for which people already have a positive perception are also most associated with high or moderately high trust in the national civil service, providing public institutions with leverage to further enhance trust levels (Figure A.2). Chief among them are three measures of reliability: First, higher satisfaction with administrative services, which two thirds across the participating countries are already satisfied with, is associated with a 4.7 percentage point increased likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in the national civil service. Believing that institutions use personal data for legitimate purposes only, which an average of around one in two do, is associated with an increase of 3.1 percentage points. Finally, being ready to protect people’s lives in a large-scale emergency, which half of individuals are confident in, is associated with a 2.7 percentage point increase in the likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in the national civil service. Fairness in dealing with people’s applications for services and benefits is associated with a 2.6 percentage points higher likelihood of trust.

While the majority of public governance drivers for trust in the national civil service refer to day-to-day interactions between citizens and government, some refer to complex policy issues. The most impactful variable on trust in the national civil service, for which many respondents have a more negative perception, is the likelihood that government would adopt the opinions expressed in a public consultation on reforming a policy area. A positive perception of this dimension of openness, currently displayed by only one third of respondents, is associated with a 2.6 percentage points increase in the likelihood of high or moderately high trust in the national civil service (Figure A.2). Focusing on improving perceptions in this area could thus have a moderately positive impact on raising trust in the national civil service.

In addition to these variables, other public governance drivers of trust also have a positive and significant association with trust in the national civil service. These include ensuring that people feel they have a say in what government does, that civil servants are seen as having integrity, that decisions are based on the best available evidence, and among the day-to-day interactions, that complaints about public services lead to changes, that people are treated equally and that clear information about public services are available.

Figure A.2. Ensuring that public services are perceived as reliable can maintain high levels of trust in the civil service

Percentage point change in high or moderately high trust in the national civil service in response to a more positive perception of the public governance variables (X-axis) and the unweighted OECD average share of the population with a positive perception of the noted variables (Y-axis)

Note: The figure shows the statistically significant determinants of self-reported trust in the national civil service in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, including whether they voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at the p<0.01 level.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

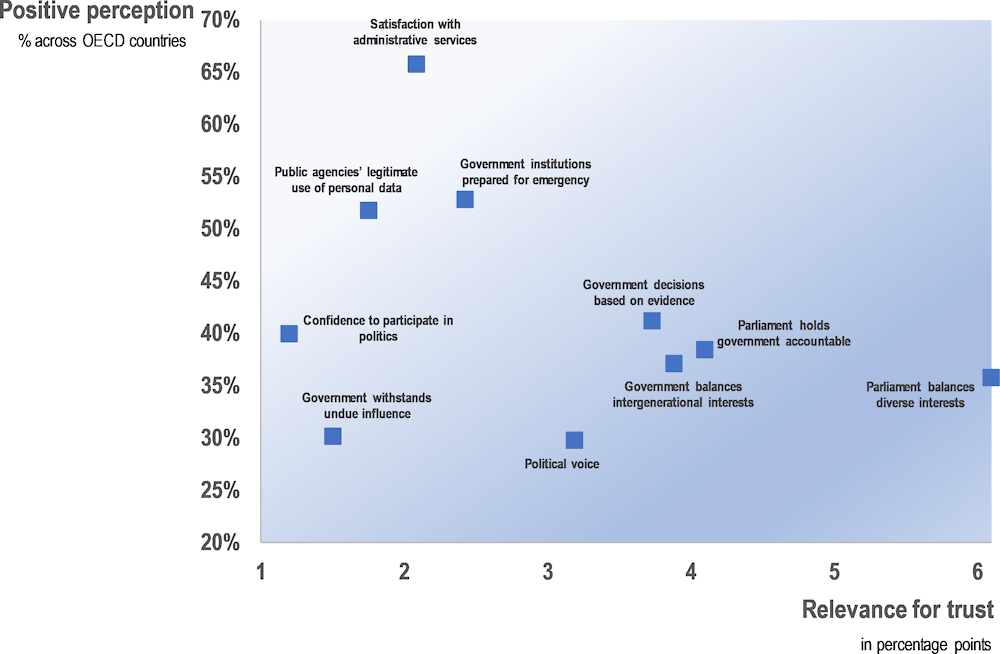

Trust in parliament is higher if it is perceived to balance the interests of different groups and to hold government accountable

In the face of a generalised disaffection for parliaments – with fewer than four in ten reporting high or moderately high trust in it – having a higher confidence in the ability of public institutions to balance intra-country and inter-generational needs and interests are highly correlated with trust in the national parliament.

An effectively perceived oversight function also has a large positive association with trust in parliament. Indeed, this accountability dimension of integrity turns out to have the second-highest association with trust in the national parliament (Figure A.3). And the dimensions of evidence-based decision making and of ensuring political voice, which are important drivers of trust in the national government, are also important drivers of trust in parliament.

The other public governance drivers related to a higher likelihood of trust in parliament also for the most part relate to complex decision making, but a few also relate to day-to-day interactions with the public. In the former category are drivers related to political agency (believing that people like oneself have a say in what government does and being confident to participate in politics); integrity (finding it likely that the national government refuses to take a decision in favour of a corporation that could be harmful to society); and reliability (emergency preparedness). In the latter category are satisfaction with administrative services and finding it likely that government institutions use personal data only for legitimate purposes.

Figure A.3. Confidence in parliament’s role in holding government to account and legislating fairly can boost trust

Percentage point change in high or moderately high trust in the national parliament in response to a more positive perception of the public governance variables (X-axis) and the unweighted OECD average share of the population with a positive perception of the noted variables (Y-axis)

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in the parliament in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, including whether they voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at p<0.01.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

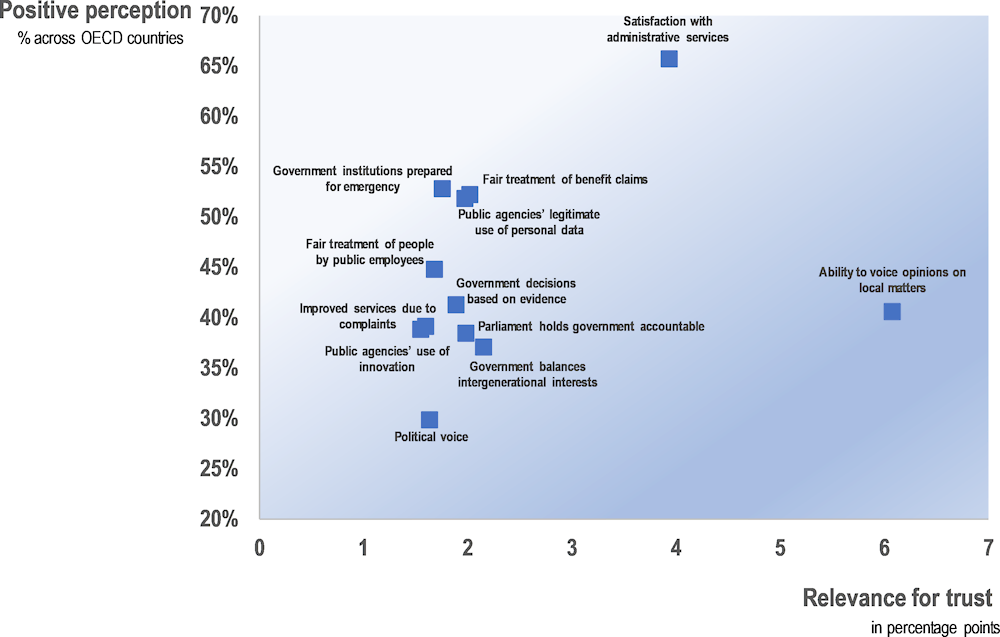

Being open to feedback from the public is the single most important driver of trust in the local government

For trust in local government, one variable stands out as a focus for increasing trust: Individuals who find it more likely that local government would give them an opportunity to voice their opinion when taking a decision affecting their community are 6.1 percentage points more likely to have high or moderately high trust in the local government (Figure A.4). An average of 41% of respondents find it likely that local government would indeed be open this way.

The reliability and fairness drivers of satisfaction with administrative services and treating service applications fairly also impact trust in the local government. Being satisfied with administrative services is associated with a 3.9 percentage points higher likelihood of high or moderately high trust in local government, while believing that their application would be treated fairly raises is associated with a 2 percentage points increase (Figure A.4).

Finally, and perhaps counterintuitively, the ability of the national government to balance intergenerational interests, which only 37% think is likely, is also associated with a higher likelihood of 2.2 percentage points of having high to moderately high trust in the local government (Figure A.4). A potential interpretation is that people care about the long-term planning capacities of all public institutions, and that the perceived capacity of the national government to balance intergenerational interests, which the survey measures, is highly correlated with the perceived capacity of local government to think strategically about issues with long-terms implications, which the survey does not measure. The included variable can then be interpreted as an imperfect proxy measure of the long-term planning capacity of local governments.

Figure A.4. Willingness to let people voice opinions about decisions that affect their community has the highest potential for increasing trust in local government

Percentage point change in high or moderately high trust in local government in response to a more positive perception of the public governance variables (X-axis) and the unweighted OECD average share of the population with a positive perception of the noted variables (Y-axis)

Note: The figure shows the statistically significant determinants of self-reported trust in the local government in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics, including whether they voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at the p<0.01 level.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Socio-economic background and partisanship as influencers of trust

People’s demographic and socio-economic background as well as their alignment with the current government in power affects their perception of public institutions. This can be seen in a simple analysis in the share of people with high or moderately high trust across groups with different characteristics. But to a lesser extent, it also holds true when analysing multiple trust drivers and background characteristics jointly.

At the individual level, the OECD Trust Survey finds that on average, women, young, and less educated people tend to have lower trust in the national government (Chapter 2). However, these relationships do not always hold in the regression analyses that control for multiple drivers at the same time. In particular, the difference between the likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in local government, the national civil service and national parliament does not exist when comparing men and women with otherwise similar backgrounds and public governance perceptions; and is very small for the national government (an average marginal effect of -1 percentage point). An explanation for this finding is that different perceptions of the public governance drivers, perceptions of political agency and partisanship between men and women (almost, in the case of the national government) entirely account for their differences in trust levels.

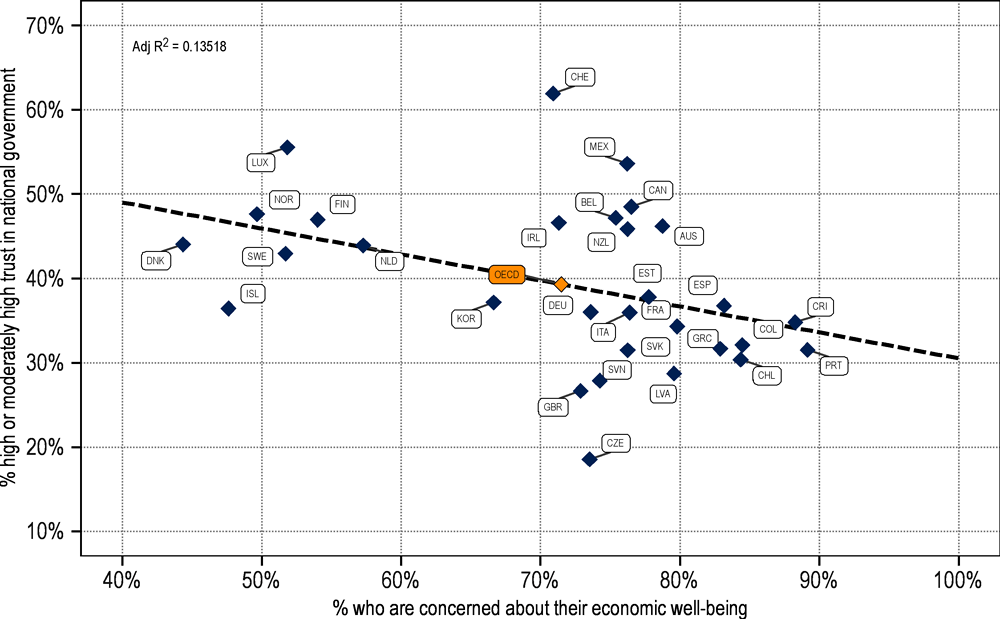

At the macro level, an important pathway through which economic, environmental, public health and security trends are likely to affect trust levels is through their impact on how stable and secure individuals feel. Findings from the OECD Trust Survey suggest that worries about the economic and financial well-being of one’s own household are negatively correlated with trust in the national government. However, this correlation is not very strong at the country level (Figure A.5). Evidence from the survey in Chile suggests that people who are more afraid of becoming the victim of a crime likewise have lower trust levels; echoing a finding of a 2023 study on the drivers of trust in public institutions in Brazil (OECD, 2023[1]).

The relationship between micro-perceptions and macro-trends, for example when it comes to the economic well-being of one’s household and the health of the economy, are complex. They not only relate to trends in main economic indicators such as GDP growth and the unemployment rate, but also to individual experiences within their immediate environment, their socio-economic background and the perceived social net provided by the tax-benefit system. For example, people with unstable employment appear to judge the performance of the economy based on poverty rather than the unemployment or growth rates (Hellwig and Marinova, 2022[2]); while more economically secure individuals appear to pay more attention to GDP, unemployment and inflation factors when determining how satisfied they are with economic conditions (Fraile and Pardos-Prado, 2013[3]). Rising job insecurity and the outpacing of costs of essential goods and services such as education and housing compared to overall inflation (OECD, 2019[4]) can have a higher impact on perceived economic insecurity of one’s own family than the economic growth rate by itself. Perceived financial vulnerability lowers the likelihood of having high or moderately high trust in the national government and parliament by two percentage points, but has no statistically significant impact at the 0.01 significance level on trust in local government and the national civil service.

Figure A.5. In countries where concerns about the economic well-being of one’s household are more widespread, trust in the national government tends to be lower

Share of respondents reporting high or moderately high trust in national government and share of respondents who have concerns about their household’s finances or overall well-being in the near future, 2023

Note: This scatterplot presents the share of high or moderately high responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust your national government?”, equal to the values of responses 6-10 on the response scale, on the y axis. The x axis presents the share of share of respondents who answered ‘somewhat’ or ‘very concerned’ to the question “In general, thinking about the next year or two, how concerned are you about your household's finances and overall economic well-being?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

At the individual level, the Trust Survey finds that those who feel politically empowered and aligned with the current government tend to have more trust in both the government and administrative institutions. However, in the regression analyses, we can clearly see that much of the raw difference in trust between those who voted for and did not vote for the current government are related to other characteristics and their perceptions of public governance drivers. In particular, while individuals who voted for or would have voted for one of the parties in power are ten percentage points more likely to have high or moderately high trust in the national government, this difference is much smaller than the unadjusted partisan trust gap of 27 percentage points (see Chapter 2). Moreover, this marginal effect already drops to three percentage points when it comes to trust in the national parliament. For the local government and national civil service, in turn, there is no statistically significant (at the 0.01 level) relationship.

Of course, people’s support for the current government in the last election can also colour how they perceive the public governance drivers, but reassuringly, it has little impact on what people self-report as significant in determining their trust levels. Moreover, it also does not affect the statistical relationship between the trust drivers and trust outcomes.

In addition to responding to hypothetical situations related to the different aspects of public governance, 2023 Trust Survey respondents were also asked to indicate which factor contributed most to their trust in the national government among six options that intended to capture government competencies, integrity, openness, adherence to electoral promises, and intergenerational fairness, as well as political preferences (“Government policies match my preferences”). Responses to this question show that, on average, only 26% of respondents cite government policies matching their preferences, the least frequently mentioned factor. In contrast, 59% selected “government officials abide of the same rules as everybody” as the main factor shaping their trust levels. Our analysis finds that respondents think similarly about which factors have the highest impact on whether they trust the government, regardless of whether they have voted for the current government. People who did not vote for one of the parties currently in power put slightly more emphasis on integrity; and people who (would have) voted for one of the governing parties put slightly more emphasis on the match between their policy preferences and government policies. But otherwise, patterns are very similar between the two groups. This finding suggests that while support or opposition to the current government in power can affect how people judge the performance of public institutions and how much they trust them, the criteria that shape their trust in the national government do not systematically vary.1

Assessing the extent to which changes in trust levels are related to changing perceptions of public governance drivers

Trust levels in some of the countries participating in the 2021 and 2023 Trust Survey changed quite strongly, calling for an explanation of how they came about. Trust in public institutions are affected by a multitude of factors. Many of these factors are measured by the Trust Survey and included in the econometric analysis above. However, other factors, related for example to the political cycle, can also lead to fluctuations in trust levels. A natural question is therefore to what extent changes in the perception of public governance drivers and of background characteristics are behind these changes in trust levels.

The simple comparison in Chapter 1 between changes in the average perceptions in the public governance drivers of trust and in the share with high or moderately high trust in the national government provided first insights into this question. In particular, countries in which public perception across all public governance drivers improved over the two years also saw increases in the share of people with high or moderately high trust in the national government; and the opposite was true in countries where average perceptions across all public governance drivers deteriorated (Annex Table 1.A.2 in Chapter 1). However, for the ‘in-between’ cases of countries where perceptions of some public governance drivers improved and others stayed constant or became worse, this simple comparison is insufficient to determine to what an extent changes in trust levels can be attributed to changes in trust drivers.

An econometric analysis is therefore needed to address this question more precisely. Decomposition analysis has traditionally been used to analyse to the extent to which differences in outcomes between two groups, such as in the earnings of men and women, can and cannot be attributed to differences in their characteristics. We apply a common decomposition method, a two-fold Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition, to understand what share of the change in trust levels in each of the individual countries that participated in the 2021 and 2023 OECD Trust Survey can be explained by changes in the public governance drivers and background characteristics, and what share cannot be.

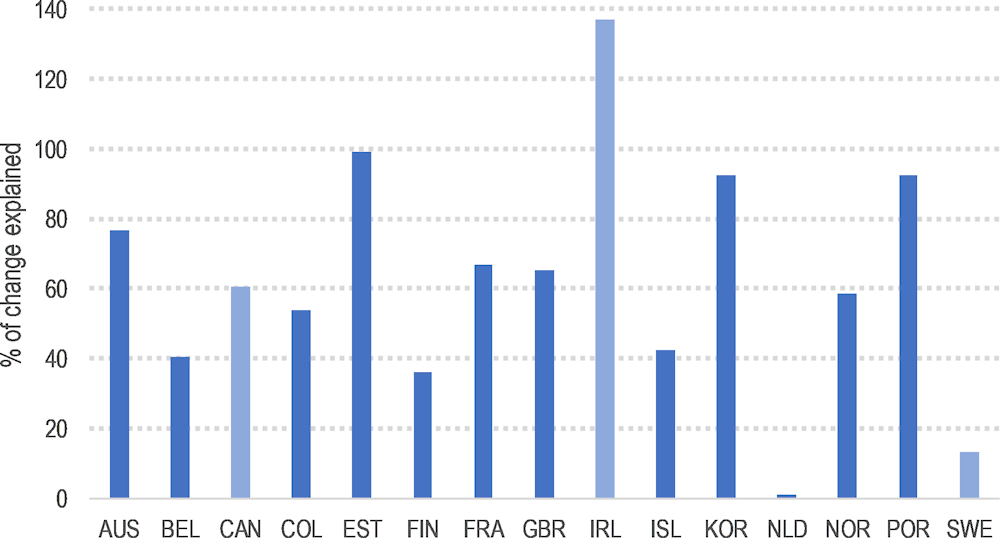

Findings from the decomposition analysis show that for the majority of countries with available information on the trust levels and drivers in the 2021 and 2023 survey, at least thirty percent of the change in trust levels between 2021 and 2023 can be explained by the econometric model we apply in this chapter. In some countries, including Australia, Colombia, Estonia, France, Korea, Portugal and the United Kingdom, the explained share is substantially higher. This means that for example in Estonia and Korea, changes in the perceptions of the drivers can explain almost all of the change in trust levels observed between 2021 and 2023. However, in other countries, the explained difference is not statistically significant; and in Denmark and the Netherlands, the explained difference goes in the opposite direction from the change in trust levels that is actually observed.

Figure A.6. In half of the countries with available information, a large part of the change in trust levels between 2021 and 2023 can be attributed to changes in the public governance drivers

Percentage of difference in share with high or moderately high trust in the national government between 2021 and 2023 explained by the public governance drivers and background variables

Note: The figure shows the share of the difference in the proportion of people with high or moderately high trust in the national government between 2021 and 2023 that can be explained through changes in the public governance drivers and background variables. The results are obtained through a two-fold Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. The explained difference are not statistically significant (at p<0.01) for the countries shown in light blue (Canada, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden). For Denmark and Luxembourg, the difference is likewise not statistically significant, but changes in the public governance drivers suggest that the change in trust levels would be in the opposite direction from the observed change. The decomposition includes the variables on public governance drivers that are stable between 2021 and 2023 as well as the respondents’ age group, education group, gender, financial concerns and whether they voted or would have voted for the current government.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

Different factors may contribute to the quite different outcomes in terms of the share of the trust gap which can be explained by the model. A first difference may be that public governance drivers that are particularly relevant in a given country are or are not included in the survey. For example, the high significance of some of the new variables in the 2023 Trust Survey suggests that they cover aspects of public governance that matter to individuals and that were not previously covered by the other public governance variables. Since they were not included in the 2021 Survey, they can however not be accounted for in this decomposition analysis. Second, it is also possible that factors related neither to the measured background characteristics nor to perceptions of public governance drivers could have an impact on trust levels. For instance, the political cycle may have an impact on trust levels that is not fully captured by the public governance drivers. For example, increased optimism after a recent election may not translate to more positive assessments of the competencies and values of public institutions. Instead, it may lead to more people reporting high or moderately high trust in the national government. The exclusion of these factors means that the model can only ever explain part but not all of the variation in trust levels. Third, a changed pertinence of specific public governance drivers, for example due to a different media environment, can also contribute to changes in how public governance drivers relate to trust. For example, in 2021, people may have given more importance to pandemic or emergency preparedness than they did in 2023.

Box A.1. Logit regression assessing the significance of different factors related to trust

The econometric results presented in this annex are logistic regression analyses for establishing the main drivers of trust in the national government, the local government, the civil service and national parliament in 30 OECD countries. Detailed regression results will be presented in (Ciccolini and Kups, forthcoming[5]).

Based on the OECD Framework on the Drivers of Trust, respondents’ perceptions of the responsiveness, reliability, openness, integrity and fairness of public institutions as well as their feelings of political agency are expected to be the main drivers of trust in the three institutions. The survey question measuring trust in each institution separately is phrased as follows: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following?”. In the regression analyses, trust is recoded as a binary variable (low or no trust: 0-4 and high or moderately high trust: 6-10). Neutral responses (5) and “don’t know” are excluded.

The analysis operationalizes government competencies (including satisfaction with administrative services) and values through 19 variables, measured on a 0-10 response scale and standardized for the analysis. Political agency is operationalized through the variables on internal and external political efficacy, meaning an individual’s confidence of participating in politics and their perception that people like them have a say in what government does; and perceptions of government actions on global and long-term challenges through variables on confidence in the country’s success in reducing greenhouse emissions, and confidence that the government balances the interests of current and future generations.

The following explains the technical details about the econometric analysis.

Model specification: All models control for individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, education, self-identified belonging to a discriminated-against group), interpersonal trust and experiencing financial concerns. It also controls for whether they voted (or would have voted) for one of the parties currently in power. They include country fixed effects in the cross-country analyses and year fixed effects in the analyses pooling data from both survey rounds. All models include survey weights. Missing data are excluded using listwise deletion.

Technical interpretation: The statistically significant drivers are shown as average marginal effects. Statistically significant refers to those independent public governance variables included in the logistic regression model that resulted in p<0.01. The technical interpretation of the effect of government’s reliability in taking evidence-based decisions on trust, for example, is that a one-standard-deviation increase in perceived reliability is associated with a 6.8 percentage point increase in trust in the national government. Or – taking into consideration all other variables in the model – all else being constant, moving from the average citizen to one with a typically higher level of confidence in government’s reliability is associated with in a 6.8 percentage point increase in trust in the national government.

The regression results require a cautious interpretation, refraining from implying that these significant variables causally increase trust. All variables included in the regression models are correlated and the direction of the relationship between trust and perceptions of public governance may be reciprocal. However, the results are largely robust to the choice of the model. For example, the direction and significance of the results are similar when an ordinary least squares model or a logit model in which the explanatory variables (public governance drivers) are likewise recoded as 0-1 indicator variables (where the ‘1’ corresponds to 6-10 on the response scale and ‘0’ to responses 0-5 and ‘don’t know’) are applied.

References

[5] Ciccolini, G. and S. Kups (forthcoming), Identifying the public governance drivers of trust - An econometric analysis of the OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, OECD.

[3] Fraile, M. and S. Pardos-Prado (2013), “Correspondence between the Objective and Subjective Economies: The Role of Personal Economic Circumstances”, Political Studies, Vol. 62/4, pp. 895-912, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12055.

[2] Hellwig, T. and D. Marinova (2022), “Evaluating the Unequal Economy: Poverty Risk, Economic Indicators, and the Perception Gap”, Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 76/1, pp. 253-266, https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129221075579.

[1] OECD (2023), Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Brazil, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fb0e1896-en.

[4] OECD (2019), Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/689afed1-en.

Note

← 1. This finding that the self-reported criteria do not differ between (would be) voters and non-voters for the current government are backed up by results from econometric analyses. In particular, when separate regressions of trust in the national government on the public governance drivers and background characteristics that are otherwise identical to those described in the “Responsiveness to evidence, balancing intergenerational needs and ensuring political voice are highly associated with trust in the national government” section are run for individuals who voted for (or would have voted for) and did not vote (or would not have voted) for the current government, the most important drivers of trust for example in the national government and in the national civil service remain the same.