Trust is an important measure of how people perceive government institutions. This chapter begins by describing the context in which the 2023 Trust Survey data collection took place. It then outlines levels of trust in public institutions at all levels of government across OECD countries, tracking changes since 2021. The chapter also offers an overview of people’s perceptions of their day-to-day interactions with public institutions and government decision making on complex policy issues, identifying the main public governance drivers of trust. The chapter’s annex details the OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions and traces the evolution of government reliability, responsiveness, openness, fairness and integrity perceptions in the twenty countries that participated in both the 2021 and 2023 Trust Surveys.

OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions – 2024 Results

1. Overview: New trends, persistent patterns and necessary changes

Abstract

1.1. Context matters: people’s concerns in 2023

People living in OECD countries have experienced several important shocks since the start of the decade, including a pandemic, rising inflation, and war in close proximity or with major geopolitical consequences. These shocks are likely to affect what people consider as important issues for their countries and their personal lives and thus determine what aspects of government performance they pay particular attention to and, as a result, their trust levels (de Blok, 2023[1]).

Data collection for the 2023 OECD Trust Survey took place in October and November 2023.1 At this point, the landscape for global economic growth exhibited signs of both moderation and resilience (OECD, 2023[2]). While the global energy crisis initially drove up inflation, gradual moderation was observed as supply chains adjusted, though inflation levels remained above central bank targets and pre-pandemic levels (OECD, 2023[3]). At the same time, low unemployment persisted alongside pressing labour shortages, challenging various industries. Public services, including health services, were under strain amid increased demand and resource constraints. Geopolitically, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and the Hamas terrorist attacks resulting in Israel’s military intervention in Gaza added to economic and policy uncertainty.

In parallel, political polarisation, partially fuelled by mis- and disinformation, visibly increased, possibly exacerbating social tensions and political disengagement. It also likely hindered government’s ability to address policy challenges, as extreme partisanship makes social and political consensus on reforms more difficult.

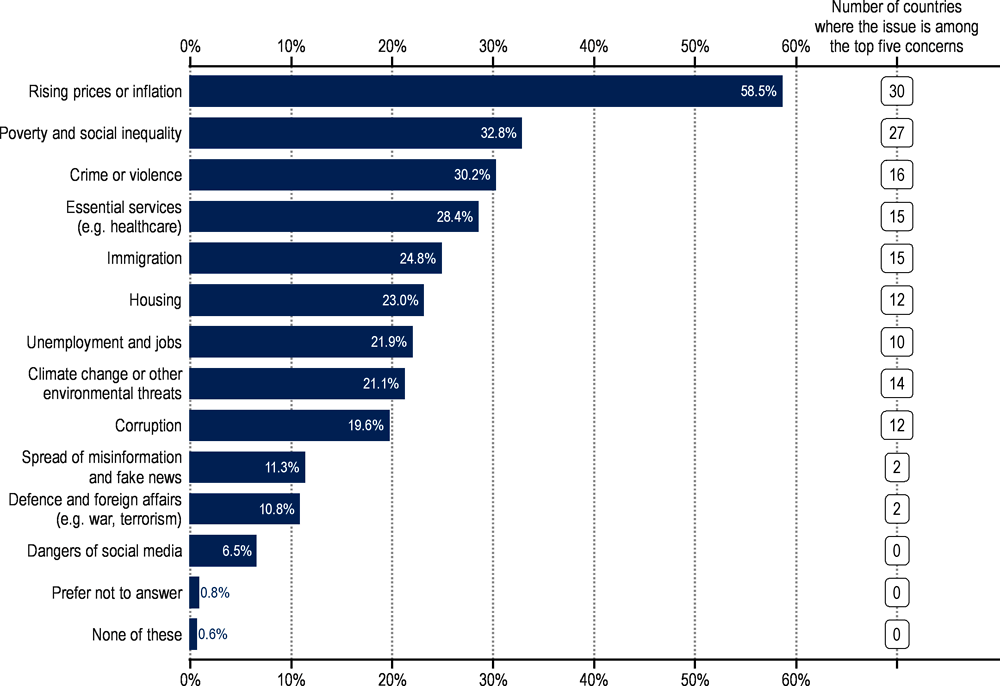

The uncertainty during this period is reflected in significant concerns about the economy, both at a macro and personal level, in surveyed countries. An average of 59% of people identify inflation as one of the three most important issues facing their country (Figure 1.1),2 making it by far the most frequently cited concern. Poverty and social inequality are cited as top concerns by an average of 33% across the participating countries, and unemployment and jobs by 22%. At a personal level, an average of 71% indicate that they are somewhat or very concerned about their household’s finances and economic well-being over the next one to two years.

Figure 1.1. Economic concerns are at the forefront of people’s minds

Share of population who view policy issue as among the three most important ones facing their country, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD average of responses to the question “What do you think are the three most important issues facing [COUNTRY]?”. Immigration was not a response option in Mexico and Norway. The listed number of countries where the issue is among the top five concerns relates to the number of countries where the issue has among the five highest proportions of mentions among the respondents.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

A second important area of concern in many countries is individual and national security. An average of 30% of people across participating countries name crime or violence among the top three issues facing their country, and 11% are concerned about defence and foreign affairs, including war and terrorism. On both concerns, however, the variation between countries is very large: While only 4% name violence among their top concerns in Estonia, the share exceeds 60% in Chile (62%), Costa Rica (63%), Mexico (70%) and Sweden (65%). In countries in closer proximity to the ongoing war of aggression in Ukraine, concern about defence and foreign affairs is far above average, ranging from 19% in Sweden, 22% in Latvia, 23% in Norway, 25% in Denmark to 33% in Estonia. Concerns in this area are also relatively high in Korea at 20% and France at 22%.

Access to and the quality of basic services is likewise an important area of concern. On average, 28% name health and other essential services among the top three concerns for their country, reaching 45% or more in Iceland (48%), Latvia (49%), Finland (56%) and Ireland (57%). Housing, which an average of 23% identify as a top-three issue, is a particularly problematic topic in several countries including Australia (39%), Canada (40%), Iceland (42%), Luxembourg (58%) and Ireland (71%). An average quarter of respondents name immigration among the top three issues at the country level, while around a fifth each cited climate change and other environmental threats (21%) and corruption (20%).

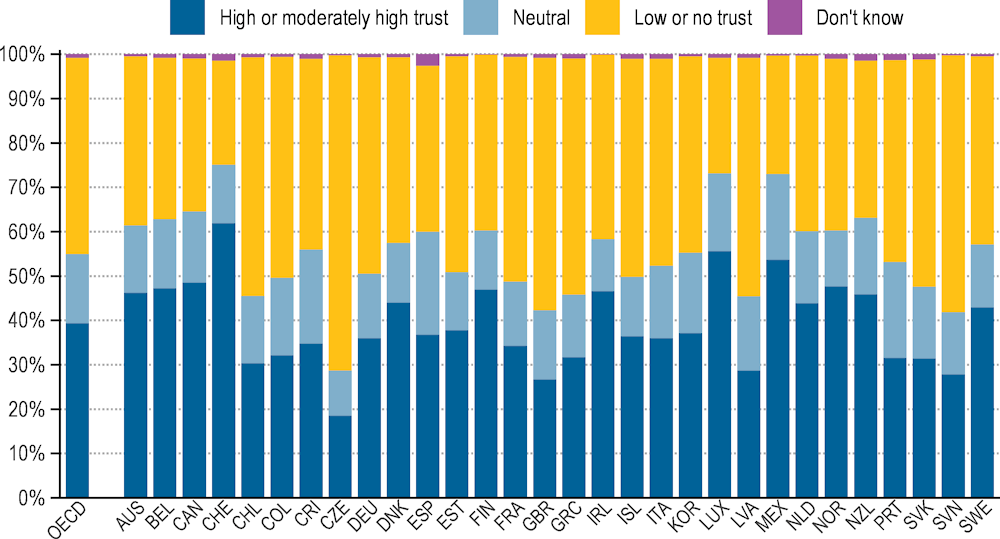

1.2. A growing share of the population expresses low trust in the national government

Trust has slightly fallen since 2021, although levels are still higher than after the global financial crisis. In 2023, around four in ten people (39%) had high or moderately high trust in their country’s national government (having selected responses 6 to 10 on a 0-10 scale). A higher share (44%) had no or low trust (Figure 1.2). 16% gave a neutral response to the question, indicating neither trust nor a lack of trust (having selected the response “5” on a 0-10 scale). Across countries, the share of people with high or moderately high trust in the national government varies strongly.3 In a few countries (Luxembourg, Mexico and Switzerland), a majority of people have high or moderately high trust in the national government, while less than one in three people do in about a third of countries. More than one in five people provide a neutral response in Costa Rica, Portugal, and Spain.

Figure 1.2. A slightly larger share of the population has low or no trust in their national government compared to those with high or moderately high trust

Share of population who indicate different levels of trust in their national government (on a 0-10 scale), 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. A 0-4 response corresponds to “low or no trust“, a 5 to “neutral“ and a 6-10 to “ high or moderately high trust“. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

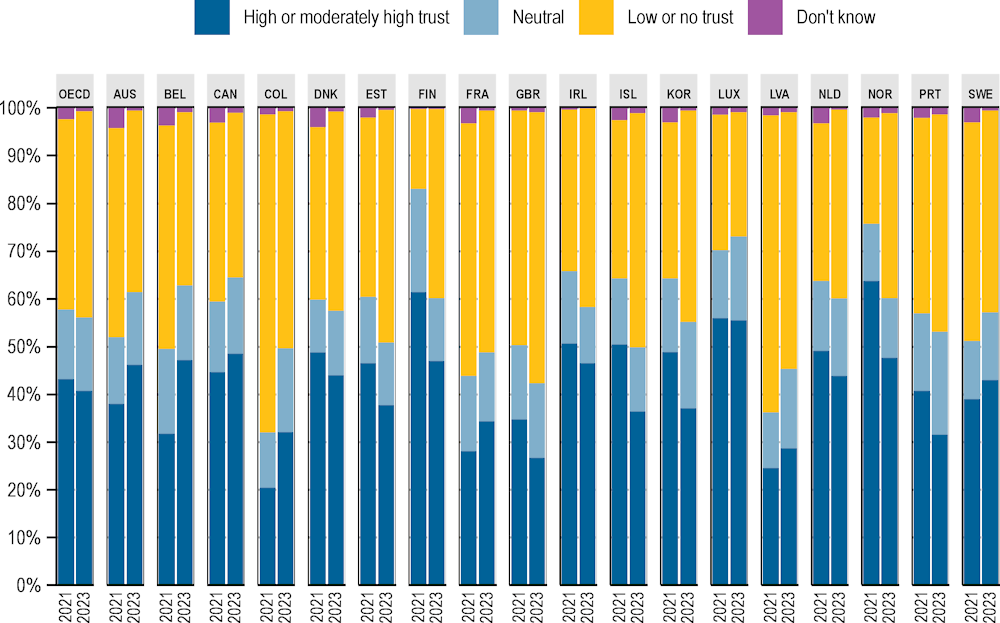

Compared to 2021, there is a modest increase in the share of people with low or no trust and a decrease in the share with high or moderately high trust in the national government. For the eighteen countries in which trust levels in the national government were measured in the 2021 and 2023 waves, the share with high or moderately high trust declined from 43 to 41% (Figure 1.3).4 The increase in the share with low or no trust is almost equivalent, from 40 to 43%. These global figures however hide important changes in trust levels in individual countries. In particular, the share with high or moderately high trust increased substantially in Belgium and Colombia, but also increased in Australia, Canada, France, Latvia and Sweden. The share declined substantially in Finland and Norway. In Finland, the timing of the 2021 survey wave, which was earlier than for other countries, may have contributed to the decline shown in the data, as the trust levels at the time may still have been boosted by the ‘rally around the flag’ effect of the Covid-19 pandemic whereby trust can increase during a national, or in this case global, crisis (OECD, 2022[4]).

Depending on each country’s situation, changes in trust level between 2021 and 2023 may also partially be due to the political cycle in each country. At the start of a government's mandate, trust often increases due to people's hopes for change and their recent participation in elections, which can boost the perceived legitimacy of the system (Hooghe and Stiers, 2016[5]), and may then decline over time as people start to evaluate the government’s performance against their expectations. Furthermore, the heightened media scrutiny and consumption of political news during elections can create more informed but potentially more sceptical citizens. However, an analysis based on eleven European countries finds the effect of general elections held 2021-2022 in some of the countries on trust is rather negligible (Gonzalez and Kyander, forthcoming[6]).

Figure 1.3. The modest shift in the average with high or moderately high trust across the OECD hides important differences across countries

Share of population who indicate different levels of trust in their national government (on a 0-10 scale), 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions across two survey waves of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. A 0-4 response corresponds to ‘low or no trust’, a 5 to ‘neutral’ and a 6-10 to ‘high or moderately high trust’. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries, for the listed countries for which the variable was available in 2021 and 2023. Mexico and New Zealand participated in 2021, but the survey for this year did not include the question about trust in the national government for these countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

Nevertheless, interesting trends are emerging in this iteration of the Trust Survey. Globally, the decrease in trust between 2021 and 2023 can be partly attributed to women and people with lower education being less confident in the national government: On average among eighteen countries, the share of women who reported no or low trust increased from 39% in 2021 to 45% in 2023; while for men, the share remained the same at 41%. Additionally, the share of lower educated people who reported no or low trust also increased by 6 percentage points.

The slight decrease in trust between 2021 and 2023 is not a positive development, but it remains comparatively modest given the current context. In comparison with the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis,5 the relative stability of public trust may reflect first a different nature of the crisis with the financial crisis being seen in part as a failure of financial regulation, while the Covid pandemic was an exogenous factor affecting the health and social outcomes of our societies. Second, it may also be a testament to the unprecedented efforts of OECD governments in upholding and strengthening the public health infrastructure and providing support to individuals and businesses affected by the pandemic.

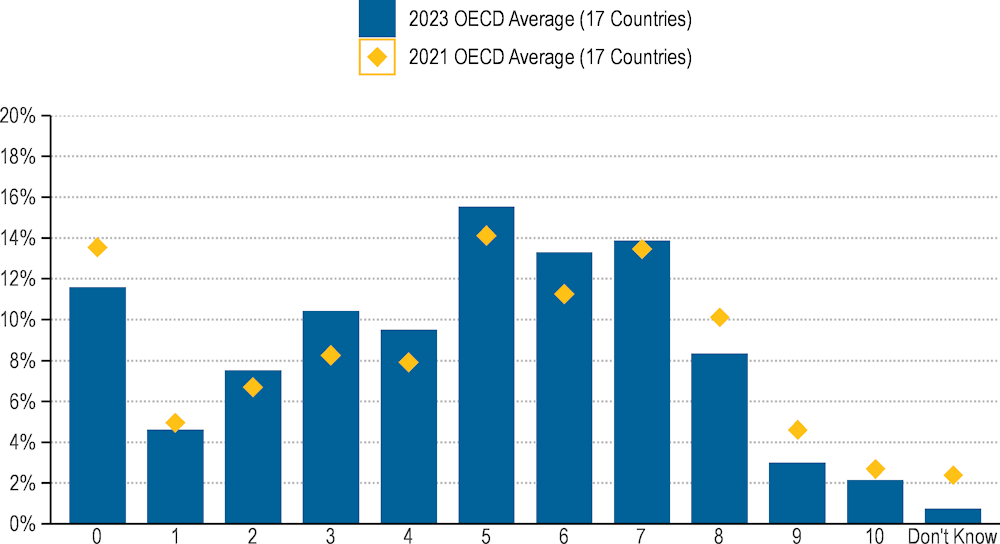

On average across the countries with available information, fewer people in 2023 indicated that they had no trust at all in the national government or selected one of the higher trust levels (Figure 1.4). The share with no trust, i.e., those who assigned a 0 to their trust in the national government, dropped by two percentage points, from 13.6 to 11.5%; and the share who selected an 8 to 10 response, indicating a high trust level, likewise dropped by four percentage points. The decrease in the share with no trust or high trust in favour of the groups with low and moderately high trust may be seen as a positive sign that fewer people either place ‘credulous trust’ in public institutions that naively assumes complete trustworthiness or have a cynical believe that they are completely untrustworthy, no matter what information is available (Norris, 2022[7]).

Figure 1.4. The share of the population who either do not trust the government at all or who have high trust has declined

Share of population who indicate different levels of trust in their national government (on a 0-10 scale), 2021 and 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD average of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the national government?”. The respective average refers to the unweighted average including Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Finland is excluded because the response scale in 2021 deviated from the 0-10 scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

1.3. Law and order institutions elicit more trust than political institutions

Public trust varies significantly across different institutions. Generally, law, order and administrative institutions garner more trust than institutions perceived as more political, such as the executive government or political parties.

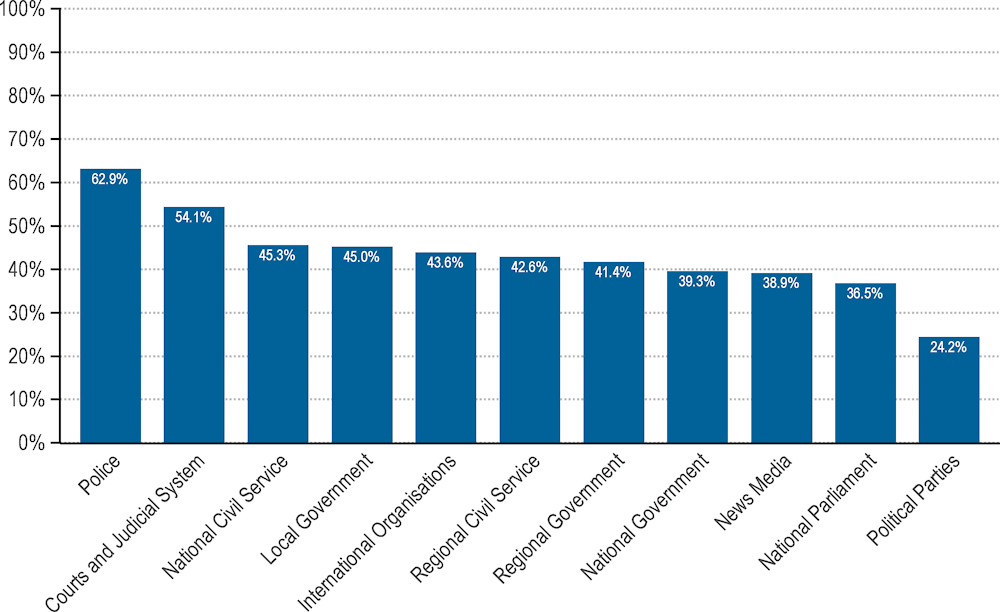

Across the OECD, the police and the judicial system are the most trusted public institutions, followed by the civil service. On average, over six out of ten people (63%) trust the police, a figure that even surpasses interpersonal trust (62%). More than half (54%) also have high or moderately high trust in the courts and judicial system. The national civil service is trusted by 45%, a level close to those of the regional or local civil service (43%). Levels of trust in the local government are equivalent to trust in the national civil service (45%). Among the twenty-one countries with regional governments participating in the Trust Survey, 41% of people had high or moderately high trust in the regional government. Finally, fewer than four in ten (39%) have high or moderately high trust in the national government, a share equal to trust in the news media (39%) and higher than in the national parliament (37%) or political parties (24%) (Figure 1.5). However, these average patterns can hide differences in individual countries.

Figure 1.5. The police and judicial system are the most trusted institutions

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the public institution and media, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD average of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [insert name of institution]?” Shown here is the share with high or moderately high trust corresponding to those who select an answer from 6 to 10 on the 0-10 response scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

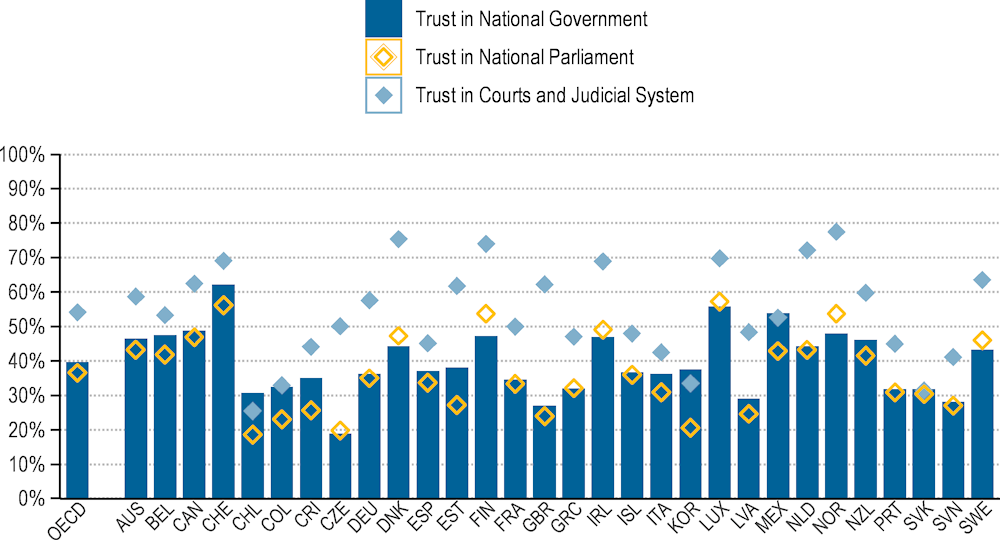

Among the different branches of national government, the (executive) government generally elicits less trust than the judicial system (which includes both lower and national-level courts), but more trust than the national parliament. This pattern holds true on average across the thirty OECD countries, as seen above, but also in the majority of participating countries (Figure 1.6). However, there are exceptions. In Czechia, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway and Sweden, the national parliament garners more trust than the national government. However, with the exception of Finland and Norway, the difference in the share that trust parliament over national government amounts to three percentage points or less. Meanwhile in Chile, Colombia, Korea, Mexico and the Slovak Republic, trust in the judicial system is equal to or even lower than trust in the national government. The gap between the proportion with high and moderately high trust in the judicial system versus the national government exceeds twenty-five percentage points in Czechia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

Since parliament and government are inherently political institutions, the higher trust placed in the judicial system is in line with expectations within a healthy democratic system (Warren, 2017[8]). Prior research suggests that judicial performance positively affects confidence in the judiciary (Aydın Çakır and Şekercioğlu, 2015[9]), and that trust in the judiciary and the belief that the judiciary is independent are almost synonymous (van Dijk, 2020[10]). Findings from the 2021 OECD Trust Survey also showed that there was a positive correlation at the cross-country level between trust in the judicial system and the belief that courts were likely to make decisions free from political interference (OECD, 2022[4]).

Figure 1.6. In most countries the national parliament is less trusted than the national government

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national government, parliament and judicial system, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [insert name of institution]?” The share with high or moderately high trust correspond to those who select an answer from 6 to 10 on the 0-10 response scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

In the past two years, trust in Parliament has generally changed in the same direction and by a similar order of magnitude as trust in the national government. The exceptions are the Netherlands and Finland, where trust in the national government decreased, but trust in the national parliament has remained stable. Trust in the courts also tends to follow similar patterns as the other two branches. However, decreases in the share with high or moderately high trust in courts and the judicial system tend to be more attenuated.

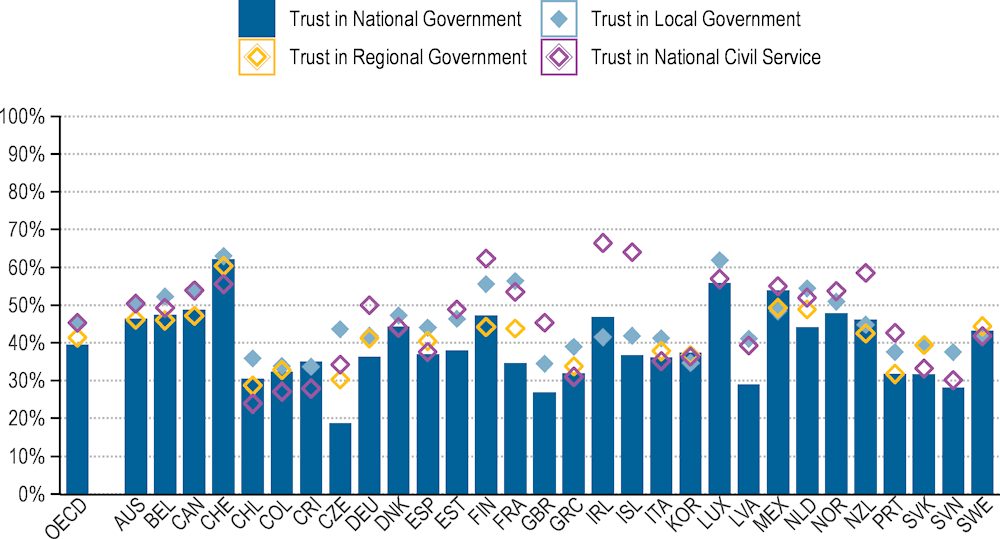

1.4. People typically perceive the civil service and local governments as more trustworthy than the national government

Turning to trust in different levels of government, trust in local government generally exceeds trust in the national and regional governments (Figure 1.7). This is expected, given that individuals are often more familiar with their local government and its actions. However, there are exceptions here as well. For instance, in Costa Rica, New Zealand, Sweden and Switzerland, trust in the two levels of government is very similar. Meanwhile in Ireland, Korea and Mexico, people are more likely to have high of moderately high trust in the national than in the local government. As regards trust in regional government, there is no clear pattern common to most countries, which could be related to the differing functions of regional governments in different OECD countries.

Across the OECD, people tend to trust the civil service more than the national government, but the pattern is far from universal. In fact, the share of the population with high or moderately high trust in the national government and the national civil service are close to identical – within two percentage point differences – in one third of the participating countries (Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Slovak Republic, Spain, and Sweden). In Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Switzerland, trust in the national civil service is lower than in the national/federal government. Conversely, the difference between the proportions trusting the civil service compared to the government exceeds ten percentage points in Czechia, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

Levels of trust in the national and either regional or local civil service are nearly equal everywhere. This could be because people view them as equally trustworthy. Alternatively, many people may not know which functions are carried out by national, regional or local civil servants. Most likely, a combination of both factors contributes to this outcome.

Figure 1.7. Trust in the local government is usually higher than trust in the regional and national governments

Share of population with high or moderately high trust in the national/regional/local government and national civil service, 2023

Note: The figure presents the within-country distributions of responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [insert name of institution]?” The share with high or moderately high trust correspond to those who select an answer from 6 to 10 on the 0-10 response scale. The question of ‘regional government’ refers to the intermediary level of government between the national and local level and can for example refer to states in federal systems, (autonomous communities) or regions. As this level does not exist in every country, it was not included in all countries. In the United Kingdom, respondents were asked to indicate their trust in the three devolved governments, regardless of where they live; the respective information is not shown in this figure. “OECD” presents the unweighted average across countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Between 2021 and 2023, trust in the civil service and trust in local government decreased by one and two percentage points on average across countries.6 However, in some countries changes were relatively large. Over the past two years, the share of people that indicated high or moderately high trust in the civil service increased by seven percentage points in Belgium and Colombia and decreased the most in Korea, Luxembourg and the United Kingdom. Similarly, trust in the local government has increased by more than four percentage points in Australia, Canada, Colombia, France and Sweden. On the contrary, the share of people that indicated high or moderately high trust in the local government decreased by more than ten percentage points in Iceland, Korea and Portugal. In Portugal, this decrease might be linked to a generalised decrease of trust in the entire political system, due to the coincidence of the survey with the peak of a significant political crisis that led to the calling of national and regional elections.

1.5. The drivers of trust in public institutions 2023: a changing landscape

The results of the 2023 Trust Survey provide a compelling picture both on perceptions by people of their day-to-day interactions with their governments and perceptions regarding societal, complex policy-making. While governments continuously need to improve on various areas in their relationship with citizens—from delivering quality services to addressing climate change--the survey suggests that today the most effective drivers for higher trust are related to complex, global and long-term policy issues where citizens feel they do not have a voice and policy decision are viewed to be taken more in the private interests rather than on the best available evidence.

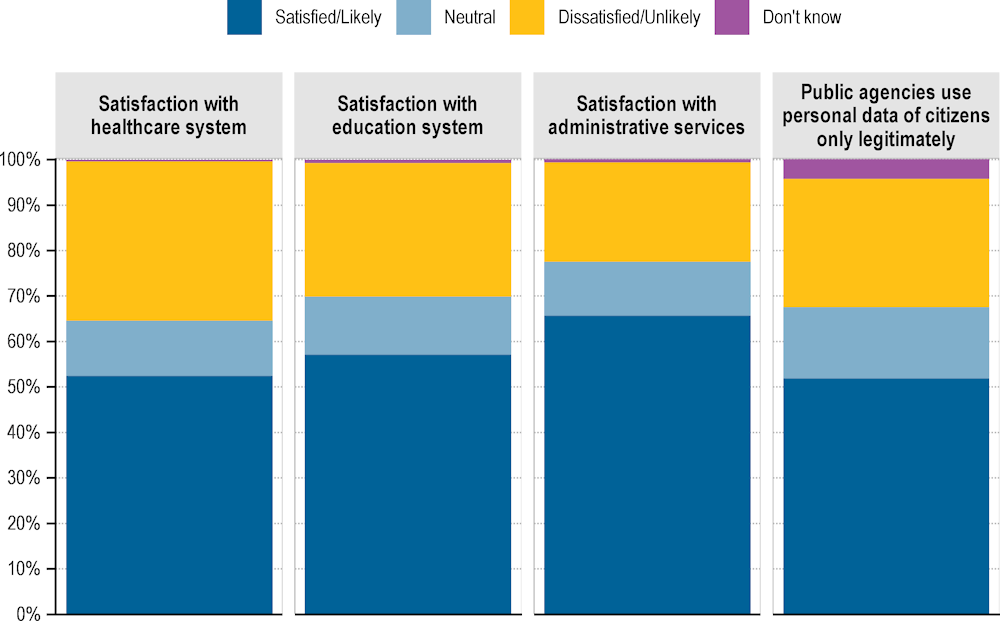

1.5.1. While day-to-day dealings with public institutions remain satisfactory, some further improvements could still boost trust levels

Both the 2021 and 2023 Trust Survey found the performance of OECD governments relatively satisfactory with regards to their day-to-day interactions with the public. For example, across participating countries, a majority continues to be satisfied with public services, such as health, education and administrative services, and trusts the government with the use of personal data (Figure 1.8). In their day-to-day interactions with individuals, public institutions therefore by and large fulfil the expectations of many people.

Figure 1.8. A majority sees public institutions as reliable providers of public services

Share of service users reporting different levels of satisfaction with the health and education system and administrative services and share of population report different likelihood that public agencies use personal data only legitimately, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD average of responses to the questions “On a scale of 0 to 10, how satisfied are you with the healthcare system/education system/administrative services in [COUNTRY]?”. For each question, respondents with recent contact are those who reply in the affirmative to the questions “In the last 12 months, have you or somebody in your household personally made use of the healthcare system in [COUNTRY]?”, “In the last 2 years, have you or somebody in your household been enrolled in an educational institution in [COUNTRY]?” and “In the last 12 months, have you personally made use of administrative service in [COUNTRY] (for example, applying for a passport, registering a birth, or applying for benefits etc.)?”. The “satisfied/likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “dissatisfied/unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice. The last bar presents the unweighted OECD average of responses to the questions “On a scale of 0 to 10, how likely do you think it is that a public agency would use your personal data for legitimate purposes only?”.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

When dealing with the public, government institutions can, and should, foster a sense of dignity among their population. A basic pre-requisite for people to feel they are treated with dignity is to ensure fairness of treatment and processes. On this behavioural dimension, the Trust Survey finds that roughly one in two respondents think it likely that their own application for a government benefit or service would be treated fairly (52%). A lower proportion – that is nonetheless higher than for many other public governance drivers – believe that public employees treat people equally regardless of their income level, gender identity and other characteristics (45%). Across these two variables, perceptions in the countries that participated in both waves worsened slightly on average, though this hides important variations across countries. More vulnerable or marginalised individuals may also have lower expectations for fair treatment than these average estimates suggest. For example, the share who find it likely that civil servants will treat them fairly when they apply for a benefit or service is 15 percentage points lower among those who identify as belonging to a discriminated-against group than among those who do not identify as belonging to such a group. This can also affect their trust in public institutions (Chapter 3).

1.5.2. Opportunity areas for government action to improve trust in their day-to-day interactions with the public

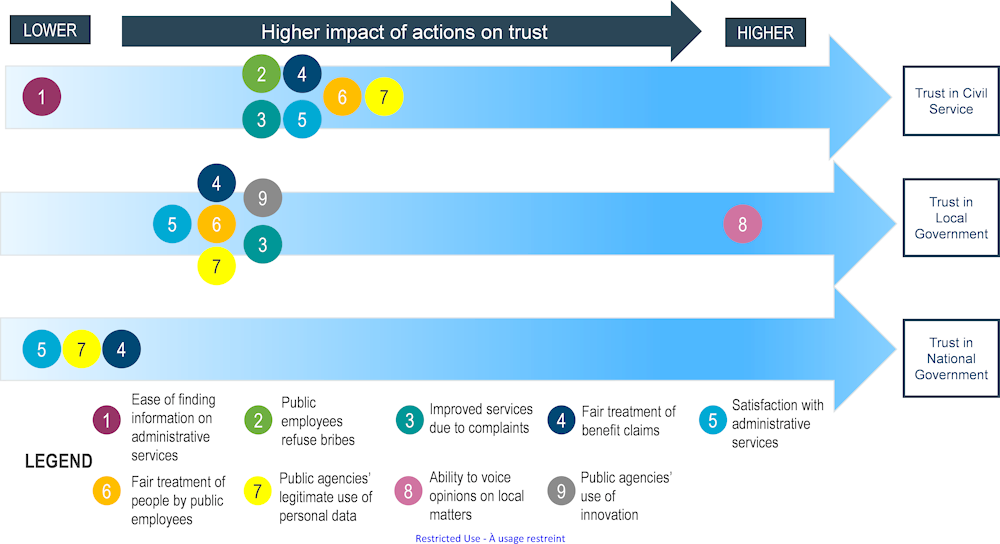

The following figure summarises the areas for actions regarding the day to day interactions between government and the public that, today, will yield the most benefits for trust in different parts of government, based on their relative importance as a driver of trust and on the lack of satisfaction or of a positive perception in this area. This represents an analysis for the 30 countries as a whole and hides important differences for individual countries that would need to be further analysed.

The positive perceptions of public services, including of fair treatment from public employees and legitimate use of personal data, are among the variables that are associated with higher trust not only in civil service and local government, but also in the national government. Therefore, governments should continue their actions in these areas. Further scope for improvement lies in the responsiveness of public institutions to adapt services to people’s needs and expectations, in particular in improving the perception of public employees’ integrity, making use of innovation and people’s feedback, and allowing greater voice on local matters (Figure 1.9).

The potential impact on trust of actions in the day-to-day interactions are more pronounced for local government and the civil service than for the national government. Today, actions to improve people’s perception that they have a voice on local matters would have the largest impact on trust in the local government. Similarly, actions to improve perception of legitimate use of data, fairness of civil servants and satisfaction with administrative services are associated with higher trust in the civil service; and the same drivers are associated with higher trust in national government, although with a smaller impact (Figure 1.9). Further details on the public governance drivers that influence trust in public institutions are in Annex A.

Figure 1.9. Drivers of trust in day-to-day interactions with public institutions: Need to focus on listening to citizens' feedback at the local level, and responsiveness and fairness of the civil service

Public governance drivers linked to day-to-day interactions that have a statistically significant impact on trust in the respective institution (national government, civil service and local government), 2023

How to read: The figure shows the combined information of the statistically significant drivers of trust in the respective institution (from the regression analysis) and the distance of the average perception of the respective driver to an 80% threshold (considered as an optimal ceiling). Drivers that are more positively associated with trust in the respective institution and for which only a low average share across the OECD have a positive perception can potentially have a higher impact on trust, as there is important scope for improvement and the improvement would likely be associated with increased levels of trust. On the other hand, drivers with a low positive association with trust and for which perceptions are already quite positive across OECD countries have a lower potential for contributing to positive improvements on trust. Nevertheless, all drivers listed in this figure are statistically significant and improvements in the respective areas can therefore all contribute to improving trust.

Note: The figure shows the statistically significant determinants of trust in the national government, civil service and local government, obtained through logistic regressions of trust in the respective institutions on the public governance drivers. The analyses control for individual characteristics, including whether people voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at the 1% significance level. For more details on the econometric analysis, including the average marginal effects associated with each variable, see Annex A.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

1.5.3. Upholding institutional accountability and listening to people’s voice when it comes to complex policy issues are key mechanisms to reinforce trust in the national government

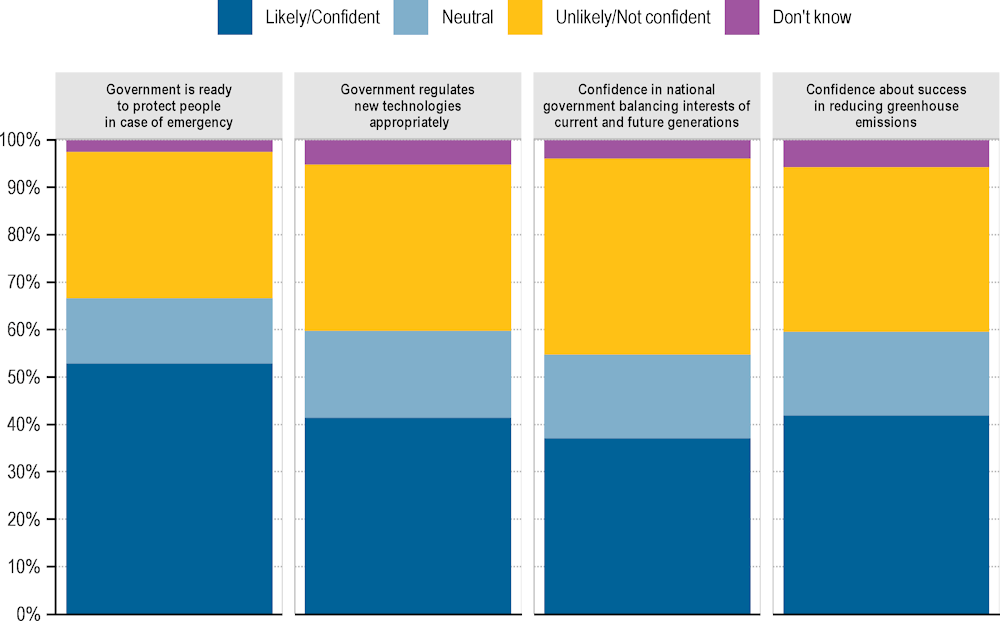

Beyond the day-to-day, government readiness to protect people’s lives in a large-scale emergency also generates trust. People across the OECD are largely satisfied with this other essential aspect of reliability, with an average of 53% of the 2023 Trust Survey respondents being confident (Figure 1.10). The positive perception has even increased on average and in 12 out of 20 countries between 2021 and 2023. This result may reflect a positive legacy of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the experience of seeing governments and public institutions respond efficiently which may have contributed to positive perceptions of their reliability and increased people’s sense of security.

In comparison to this relative satisfaction regarding the day to day interactions with government and ability to respond to a crisis, people are overall more sceptical about the ability of governments to reliably address societal challenges that require complex trade-offs or involve a high degree of uncertainty. For example, 42% think that their country will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, 41% find it likely that government can help businesses and people use new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, appropriately, and 37% are confident that government adequately balances the interests of current and future generations (Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. People are generally confident that their government is ready to protect lives in an emergency but are more doubtful about its ability to tackle challenges involving more unknowns

Share of population reporting different levels of confidence in the capabilities of government institutions to achieve policy objective, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD averages for responses to the following questions: (1) “If there was a large-scale emergency, how likely do you think it is that government institutions would be ready to protect people’s lives?”, (2) “If new technologies (for example artificial intelligence or digital applications) became available, how likely do you think it is that the national government will regulate them appropriately and help businesses and citizens use them responsibly?”, (3) “On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that the national government adequately balances the interests of current and future generations?”, and (4) “On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that [COUNTRY] will succeed in reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the next ten years?”. The “likely/confident” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely/not confident” is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and “don't know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Part of the reason why people may question their governments’ ability to address challenges with long-term and global implications may relate to a perceived lack of responsiveness that extends to all levels of government and public institutions: across the board, fewer than four in ten people believe that a majority view against a national policy would sway government to change gears (Chapter 4).

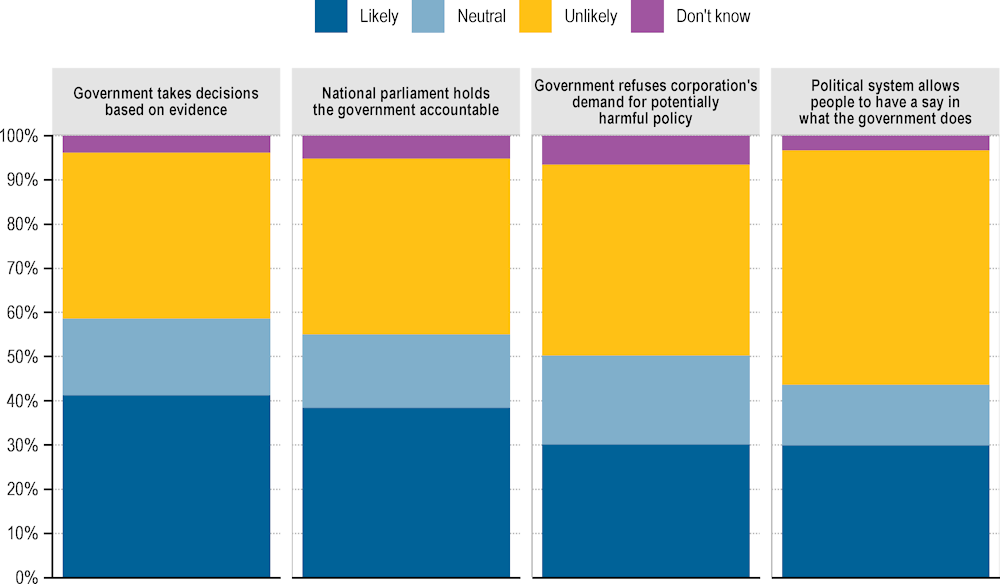

This perceived lack of responsiveness is compounded by the scale and complexity of policy issues like climate change, immigration, or inflation. These challenges also require substantial and robust evidence, necessitating policymakers to seek insights from the scientific community beyond their constituency for the public to trust that decisions are made in pursuit of the public interest. More than a third (38%) on average across OECD countries find it unlikely that government draws on the best available evidence, research and statistical data when taking decisions (Figure 1.11). This dimension of responsiveness is the question in the 2023 Trust Survey with the highest correlation with trust in the national government when analysing all trust drivers simultaneously (Annex A).

Aside from these difficulties inherent to complex decision-making, results indicate that this sense of insecurity about government’s capabilities on issues with significant unknowns stems from unmet expectations that public institutions and officials act in the public interest, are accountable to each other and to the population, and allow people to have a voice and influence decision-making processes (Chapter 4). Results from the 2023 Trust Survey show that the public remains deeply sceptical about the integrity of civil servants and elected officials. Only 30% finds it likely that government would be able to withstand lobbying by a corporation for a policy that could benefit its industry but be harmful to society as a whole (Figure 1.11).

Institutional checks and balances in democracy prevent the concentration of power and help ensure decisions are not swayed by undue influence. Nearly four in ten (38%) think it is likely that parliament can hold the national government accountable for their policies and actions, showing that on average, people have slightly more faith in the oversight and accountability safeguards between branches of government, than they do in the system’s ability to withstand pressure from private interests in the first place (Figure 1.11).

Finally, people need to feel they have equal opportunities to express opinions and preferences to steer government decision making, and to feel they are considered when the government makes decisions. Here as well, people in OECD countries have their doubts. Only 32% find it likely that government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation. This perceived lack of openness likely contributes to the low share of people (30%) who feel like the political system lets people like them have a say (Figure 1.11). This factor, along with the very important driver of confidence that government takes decisions based on the best available evidence, has a strong correlation with trust in the national government, parliament and civil service both at a country level and when analysing the relationship between trust and all public governance drivers and background characteristics simultaneously (Chapter 4 and Annex A).

Figure 1.11. Many people express concerns about the quality and integrity of democratic decision making

Share of population reporting different levels of perceived likelihood that government takes decisions based on evidence, that national parliament holds government accountable, that government would refuse undue influence, and that people have a say in what the government does, OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD averages for responses to the following questions: 1) “If the national government takes a decision, how likely do you think it is that it will draw on the best available evidence, research, and statistical data?”, 2) “How likely do you think it is that the national parliament would effectively hold the national government accountable for their policies and behaviour, for instance by questioning a minister or reviewing the budget?,” 3) “If a corporation promoted a policy that benefited its industry but could be harmful to society as a whole, how likely do you think it is that the national government would refuse the corporation’s demand?,” and 4) ‘’How much would you say the political system in [COUNTRY] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?’’. The “likely” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “unlikely” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don’t know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

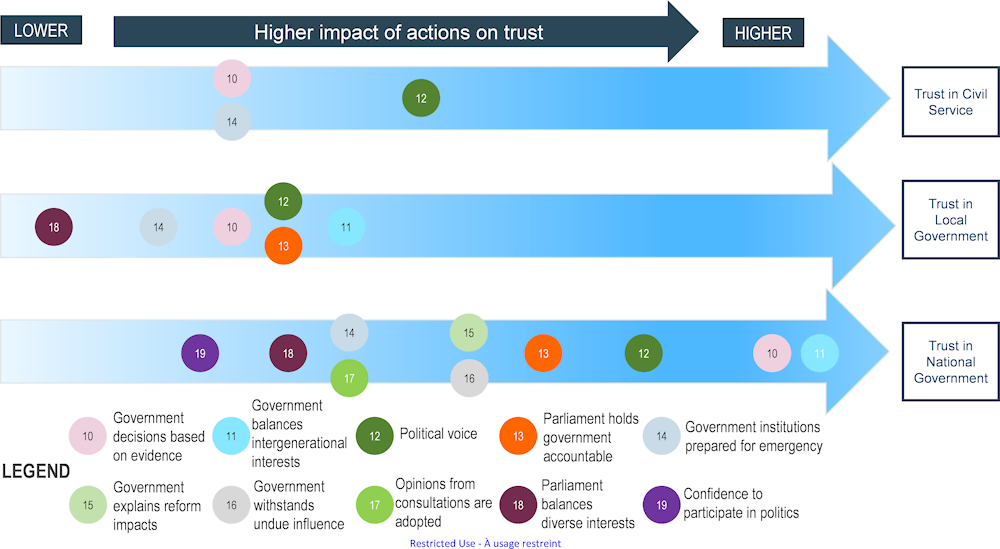

1.5.4. Opportunity areas for government action to improve trust in their decision making on complex policy issues

Similar to Figure 1.9, the following figure summarises the areas for actions regarding policy making that, today, will yield the most benefits for trust in different parts of government, based on their relative importance as a driver of trust and on the lack of trust or positive perception in this area. This represents an analysis for the 30 countries as a whole and may hide important differences for individual country that would need to be further analysed.

People’s perceptions of the ability of government and the political system to ensure competent and values-based decision making on complex policy issues is associated with a higher potential for influencing trust in the national government than their perceptions of their day-to-day interactions with government (Figure 1.12, compared to Figure 1.9). Today, actions to improve people’s perceptions that decision making is based on evidence, is fair towards different generations, listens to the people, and ensures institutions are accountable would yield the largest potential gains for trust in the national government. These variables are also associated with trust in local government and the civil service, although with a smaller impact than for national government. These results indicate that people expect key democratic principles – accountability of institutions and people’s voice - are anchored in practice to build trust in government. Other areas of action for government such as better withstanding undue influence and communicating on the impacts of reforms would also yield significant returns on trust for national government.

Figure 1.12. The drivers of trust on complex policy issues: Focus on ensuring people’s voice and best evidence in decision-making, balancing intergenerational interests, and strengthening accountability

Public governance drivers linked to decision making on long-term and global issues with an impact on trust in the respective institution (national government, the civil service and local government), 2023

How to read: The figure shows the combined information from the regression analysis of trust in the respective institutions on the public governance drivers and control variables and the distance of the average perception of the respective driver to an 80% threshold. Drivers that are more positively associated with trust in the respective institution and for which only a low average share across the OECD have a positive perception can potentially have a higher impact on trust, as there is important scope for improvement and the improvement would likely be associated with increased levels of trust. On the other hand, drivers with a low positive association with trust and for which perceptions are already quite positive across OECD countries have a lower potential for contributing to positive improvements on trust. Nevertheless, all drivers listed in this figure are statistically significant and improvements in the respective areas can therefore all contribute to improving trust.

Note: The figure shows the statistically significant determinants of trust in the national government, civil service and parliament, obtained through logistic regressions that of trust in the respective institutions on the public governance drivers. The analyses control for individual characteristics, including whether they voted or would have voted for one of the current parties in power, self-reported levels of interpersonal trust, and country fixed effects. All variables depicted are statistically significant at the 1% significance level. For more details on the econometric analysis, including the average marginal effects associated with each variable, see Annex A.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Finally, individuals’ expectations for and perceptions of public institutions are shaped not only by their own experiences, but also by information they receive from conversations, from media and from public communication directly. Unfortunately, the evolution of the information ecosystem is having significant consequences on trust. On the one hand, a substantial minority of 2023 Trust Survey respondents simultaneously have low to no trust in media and feel that government statistics are rarely or never trustworthy. They probably view the information environment as unsuitable for them to form informed opinions about public institutions’ actions and performance. On the other hand, only 39% of the surveyed population believe that governments clearly communicate about how they will be affected by a reform. In order to address these, support for a stronger pluralistic, diverse and independent media landscape, in addition to further media literacy education and public communication can all serve to empower citizens in their political agency and in holding public institutions accountable, which is needed in the current environment. Only information by government that can be checked independently and challenged will be trustworthy, which the survey reveals is a critical driver of trust.

Annex 1.A. The OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions

Trust in government and public institutions is driven by many interacting factors. The OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions distinguishes three categories of factors that influence levels of trust.

First, five main public governance drivers assess the degree to which people expect institutions to be reliable and responsive in formulating and implementing policies and services and to uphold the values of fairness, integrity and openness (Annex Table 1.A.1). Although the way these expectations are formed can differ whether related to daily policy and programme implementation or decision making on global and social issues, institutions aligning their behaviour with these expectations can foster feelings of security, dignity, and mutual respect in people in relation to these same institutions. Thus, governments can more directly influence these perceptions of public institutions’ performance and leverage them to strengthen trust.

A second aspect that drives trust in public institutions is related to the perceived capacity of government to address complex and/or global challenges. To feel secure and empowered, people do not only need to be confident that public institutions are able to manage public services in a responsive manner and willing to step in if they fall on hard times. They also have to believe that their governments have the capacity and agency to tackle major complex policy issues, and that they can do so while protecting and promoting human dignity, by upholding the public interest, maintaining checks and balance to enhance accountability and fairness, and letting people have a say.

Finally, various individual and group based cultural, socio-economic factors, and political preferences influence trust. Building trust in public institutions therefore requires a holistic approach that addresses how people perceive public governance performance but that also acknowledges that people’s demographic and socio-economic background as well as their perceptions of political agency are affecting their experiences with and perceptions of public institutions and therefore their trust in these institutions.

Annex Table 1.A.1. OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions and survey questions

|

OECD Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions |

Covered by survey questions on perceptions on/evaluation of: |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Levels of trust in different public institutions |

Trust in national government, regional government, local government, national civil service, regional/local civil service, parliament, police, political parties, courts and judicial, international organisations |

|

|

Public Governance Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions |

||

|

Competencies |

Reliability |

|

|

Responsiveness |

|

|

|

Values |

Openness |

|

|

Integrity |

|

|

|

Fairness |

|

|

|

Perception of government action on intergenerational and global challenges |

|

|

|

Cultural, Economic and Political Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions |

|

|

Governments are seen as more reliable than responsive or acting with integrity

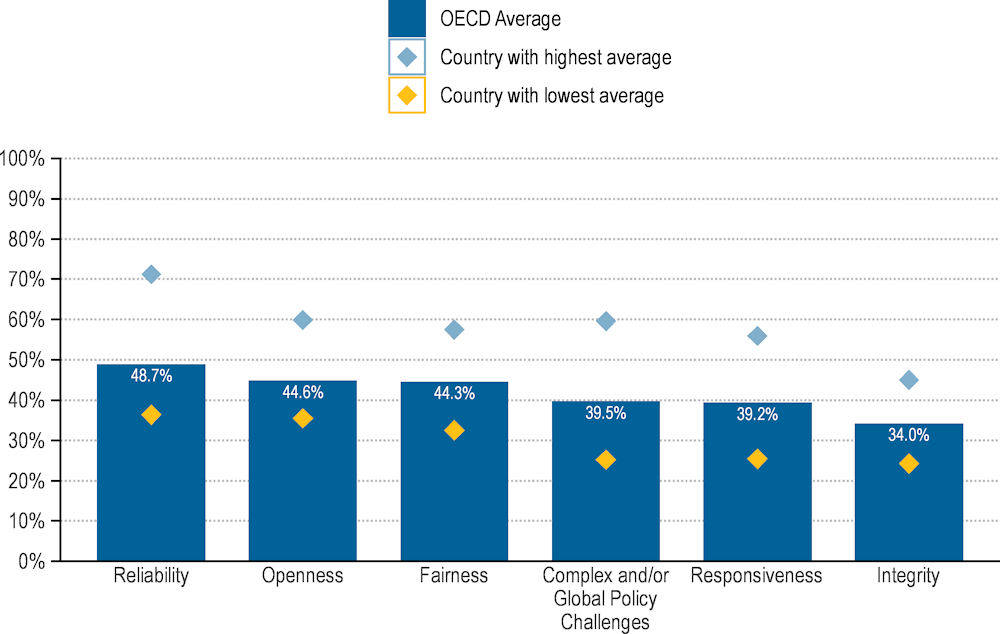

The 2023 Trust Survey finds that on average across OECD countries, almost one in two (49%) consider their government reliable, but only one-third (34%) are confident it upholds public integrity. Meanwhile, 39% have a positive perception of the responsiveness of public institutions (Annex Figure 1.A.1). Differences across countries are the largest on reliability, where in 13 of the 30 surveyed countries a majority view the government as reliable. However, as the 2023 Trust Survey includes multiple questions measuring different aspects for each of the public governance drivers, it needs to be noted that these perceptions can vary quite strongly across different aspects related to the same public governance driver in a country.

Annex Figure 1.A.1. People are more confident in their government’s reliability than its integrity and responsiveness

Share of population expressing confidence in government reliability, responsiveness, openness, integrity, fairness and ability to address complex and/or global policy challenges (average across survey questions), OECD, 2023

Note: The figure presents the unweighted OECD average of “likely” responses across all survey questions related to “reliability” (3 questions), “responsiveness” (4 questions), “integrity” (4 questions), “openness” (4 questions), “fairness” (3 questions), and “complex and/or global challenges” (2 questions). The share of ‘’likely’’ correspond to those who select an answer from 6 to 10 on the 0-10 response scale.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2023.

Compared to 2021, on average, people have slightly more positive perceptions of the reliability and openness of public institutions and slightly less in their fairness, responsiveness and integrity. However, this hides important differences across countries. In several countries – Australia, Colombia and Mexico – average perceptions across all public governance drivers improved between the two years. Not surprisingly, these are countries where trust in the national government also increased. On the other hand, in countries such as Estonia, Korea, Portugal and the United Kingdom, perceptions of the public governance drivers became more negative, contributing to a decrease in the share with high or moderately high trust in the national government (Annex Table 1.A.2).

Annex Table 1.A.2. Perceptions across the different public governance drivers often move in tandem

Percentage point changes in the share of population expressing confidence in government reliability, responsiveness, openness, integrity, and fairness (average across survey questions), 2023 compared to 2021

|

Reliability |

Responsiveness |

Openness |

Integrity |

Fairness |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AUS |

9 |

6 |

8 |

5 |

7 |

|

BEL |

14 |

7 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

|

CAN |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-2 |

|

COL |

9 |

9 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

|

DNK |

3 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

-1 |

|

EST |

-6 |

-12 |

-5 |

-7 |

-10 |

|

FIN |

27 |

9 |

20 |

5 |

-9 |

|

FRA |

7 |

2 |

2 |

-1 |

-1 |

|

GBR |

-7 |

-8 |

-5 |

-5 |

-9 |

|

ISL |

-3 |

-5 |

4 |

-1 |

-5 |

|

IRL |

1 |

-6 |

-5 |

1 |

1 |

|

KOR |

-13 |

-14 |

-11 |

-14 |

-10 |

|

LUX |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-3 |

-6 |

|

LVA |

6 |

0 |

-1 |

-4 |

-9 |

|

MEX |

4 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

8 |

|

NLD |

13 |

-2 |

-3 |

-1 |

0 |

|

NOR |

2 |

1 |

0 |

-7 |

-5 |

|

NZL |

1 |

0 |

-1 |

-6 |

0 |

|

PRT |

-15 |

-6 |

-6 |

-4 |

-10 |

|

SWE |

9 |

1 |

1 |

-2 |

-1 |

|

OECD |

3 |

-1 |

1 |

-2 |

-3 |

Note: The figure presents the change in the share of the average of “likely” responses (6-10 on the 0-10 response scale) across questions related to “reliability”, “responsiveness”, “integrity”, “openness” and “fairness”. The average refers to the questions that have remained stable between 2021 and 2023, with the exception of using the pandemic and emergency preparedness variables, respectively, for the 2021 and 2023 average of reliability; and a change in wording for one of the fairness variables, which in 2023 also referred to equal treatment of people of different income levels in addition to other characteristics. Complex and/or global challenges is excluded because only one question is repeated between the 2021 and 2023 wave.

Source: OECD Trust Survey 2021 and 2023.

References

[9] Aydın Çakır, A. and E. Şekercioğlu (2015), “Public confidence in the judiciary: the interaction between political awareness and level of democracy”, Democratization, Vol. 23/4, pp. 634-656, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.1000874.

[1] de Blok, L. (2023), “Who Cares? Issue Salience as a Key Explanation for Heterogeneity in Citizens’ Approaches to Political Trust”, Social Indicators Research, Vol. 171/2, pp. 493-512, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03256-w.

[6] Gonzalez, S. and A. Kyander (forthcoming), Do elections influence trust in government? Evidence from eleven European countries in the ESS-CRONOS 2 panel survey, OECD Publishing.

[5] Hooghe, M. and D. Stiers (2016), “Elections as a democratic linkage mechanism: How elections boost political trust in a proportional system”, Electoral Studies, Vol. 44, pp. 46-55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.08.002.

[7] Norris, P. (2022), In Praise of Skepticism, Oxford University Press.

[3] OECD (2023), “General Assessment of the macroeconomic situation”, in OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9207a760-en.

[2] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2023 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a5f73ce-en.

[4] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[10] van Dijk, F. (2020), “Independence and Trust”, in Perceptions of the Independence of Judges in Europe, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63143-7_6.

[8] Warren, M. (2017), “What kinds of trust does a democracy need? Trust from the perspective of democratic theory”, in Handbook on Political Trust, Edward Elgar Publishing, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781782545118.00013.

Notes

← 1. In Ireland, Mexico and the United Kingdom, the data collection instead took place in September and October 2023; and in Norway, it was finalised in early December.

← 2. In this report, unless otherwise noted, ‘(unweighted) OECD average’ refers to the unweighted average of the weighted country averages. The weighted country average represents the respective share within the adult population, while the unweighted OECD average represents the averages across the countries, giving equal weight to each country’s experience no matter its population size.

← 3. These values are broadly confirmed in other data sources, such as the 2023/2022 Gallup World Poll and the 2021 European Social Survey, both of which inquire about people's trust in their national government. At country-level, the various measures correlate strongly and moreover countries that tend to be highly ranked relative to other OECD countries in the other data sources, also tend to be relatively highly ranked in the OECD Trust Survey.

← 4. Mexico and New Zealand participated in the 2021 survey but did not include the question on trust in the national government.

← 5. Trends of trust in government from the Gallup World Poll, show that during the Global Financial Crisis, across the OECD, confidence in the national government decreased by 6 percentage points between 2007 and 2012. In contrast, during the Covid-19 pandemic, confidence initially even rose as part of a ‘rally around the flag’ effect, but by 2022 had stabilised at over one percentage point above the 2019 level. This stabilisation has continued in 2023, when the OECD average returned to the 2019 level.

← 6. Averages among 20 and 19 countries, respectively, which participated in both rounds of the OECD Trust Survey. Trust in the local government was not surveyed in Mexico in 2021.