COVID-19 is severely affecting communities across Canada and it is likely to speed up the adoption of automation in the workplace. Employment fell by 15.7%, or 3 million jobs, in Canada between February and April 2020, exceeding by far declines observed in previous labour market downturns. As of May 2020, employment started to rebound with an increase of about 290 000 jobs. However, the unemployment rate has continued to rise, sitting at 13.7% as of May 2020. This is the highest unemployment rate since comparable data became available in 1976. Unemployment rates across Canada range from a low of 11.2% in Manitoba to a high of 16.3% in Newfoundland and Labrador. Some provinces have started gradually easing public health restrictions, including allowing some non-essential businesses to re-open, but there is much uncertainty about the path to recovery.

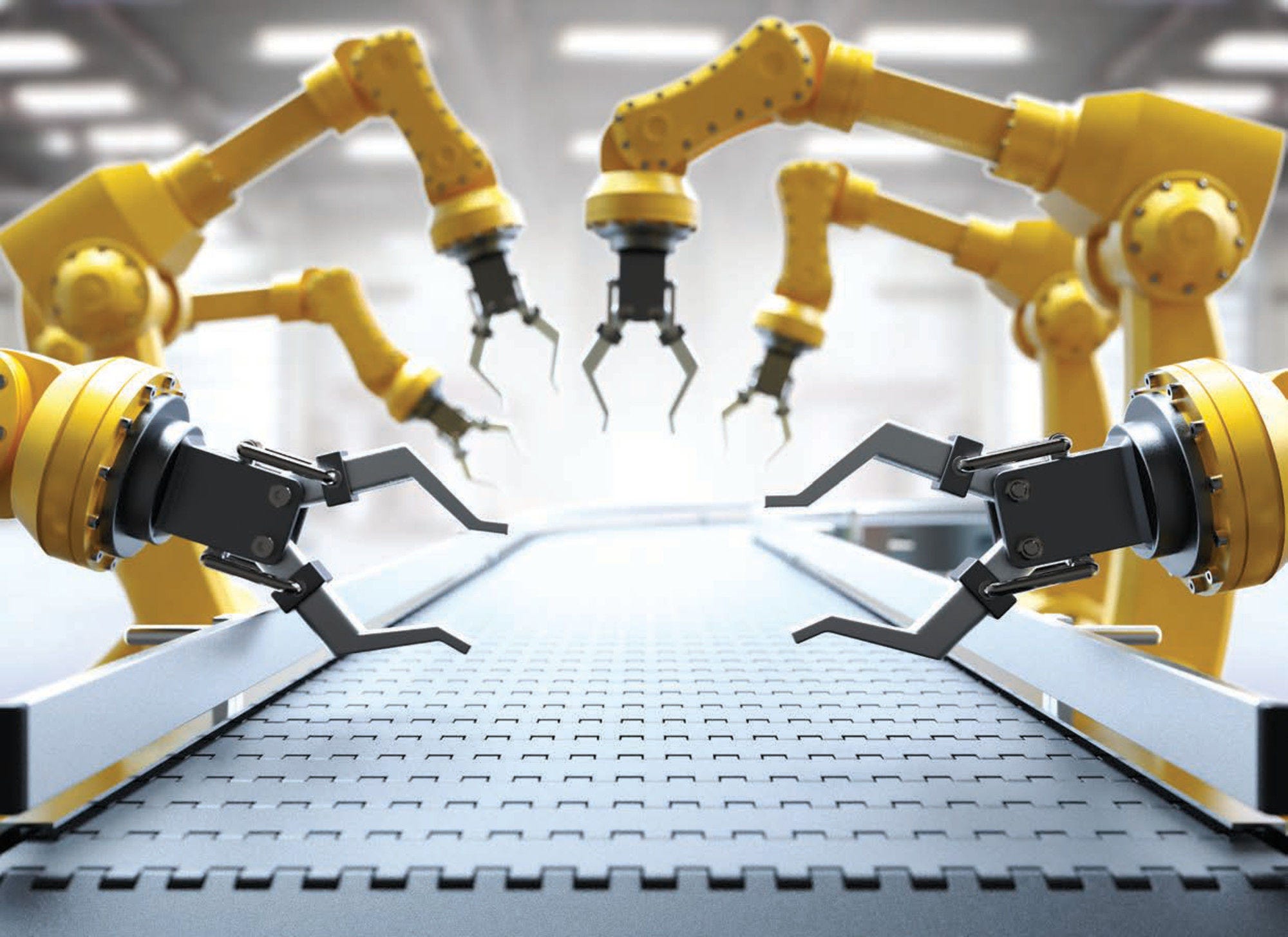

Looking to the past, automation often accelerates during economic downturns as firms look to deeply re-organise their business models. With health experts warning that social distancing measures may need to remain in place through 2021, firms may seek to expand their use of technology to reduce the number of staff that have to physically be at work. In other words, firms might want to pandemic-proof their operations. The pandemic is also likely to change consumer behaviour as people develop preferences for automated services over face-to-face interactions.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, automation was changing local labour markets in Canada. Overall, 15% of jobs face a high risk (e.g. high probability) of being automated, while another 30.6% are likely to face significant change. Automation could impact places differently. In Ontario, which represents almost 40% of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product, OECD estimates show that jobs at risk of automation amount to almost 45% of total employment – 14.7% of jobs being at high risk (or about 1.1 million jobs) and another 30.2% likely to experience significant change, representing 2.2 million jobs. The share of jobs at risk of automation across economic regions in Ontario ranges from 41.1% in Ottawa to a high of almost 50% in Stratford-Bruce Peninsula.

While automation could create inequalities in the labour market, new jobs are also likely to be created as a result of technological innovations. The good news is that 23 out of 65 economic regions (35%) across Canada have been creating jobs primarily in less risky occupations since 2011. This means that they are creating jobs primarily within occupations with a lower probability of being negatively affected by automation. Within Ontario, 4 out of 11 economic regions created jobs primarily within occupations less likely to be negatively impacted by automation between 2011 and 2018.

There are certain types of places and people within Ontario that are more likely to be impacted by the acceleration of automation. Communities most at risk of automation tend to have a higher share of jobs in the goods producing sector (e.g. manufacturing, mining, construction, and agriculture jobs). In terms of people, men are more likely to be impacted than women as those occupations facing the highest risk tend to have a higher proportion of males in the labour market. Young people, the low-skilled, and some groups already facing labour market disadvantages, could be disproportionately impacted by the introduction of new technologies within the workplace. That is because they tend to work in jobs that primarily involve simple and repetitive tasks, which can be more easily replaced by a machine.

Automation is more likely to change tasks within jobs rather than replace entire jobs, requiring workers to develop new skills. Despite a growing narrative around the importance of learning to code, for most Canadians, foundational digital skills alongside a suite of non-digital skills — in particular, inter-personal skills, such as good communication, team work, and motivation — are critical to be competitive in the labour market.

Here again, the good news is that local labour markets in Canada are primarily shifting from middle to high-skill jobs. In more than 50 out of 65 economic regions, the employment share of high-skill jobs has increased over the last decade. In addition, the demand for high-skill jobs is projected to grow in Canada over the coming decade. Occupations requiring a university education are expected to have the fastest overall employment growth, contributing to the largest share (36%) of job creation among all skill levels in Canada. Within Ontario, 7 out of 11 economic regions primarily shifted from middle to high-skill jobs between 2011 and 2018.

While policy in Canada will concentrate on supporting local employment activity in the short term in light of COVID-19, efforts in the longer term can focus on preparing communities for the upturn. Canada has already taken important steps to future-proof local communities, including by establishing the Future Skills – a federal government initiative that includes a Council and a Centre devoted to identifying labour market changes and new programme innovations. There are also a range of local initiatives aiming to improve how firms and workers use technology, such as Communitech in Kitchener, Ontario, which could be scaled up and implemented in other regions of Canada.

The following recommendations emerge from this report, focusing on future-proofing people, places and firms:

Foster demand-led training and labour market information: Canada could do so by mainstreaming an employer survey, strengthening sector-focused training programmes, and exploring the feasibility of career pathway programmes that better link young people to emerging local labour market opportunities.

Promote economic diversification, building on the skills assets of communities: Local Workforce Planning Boards as well as Local Employment Planning Councils in Ontario could play a stronger role in the development of local skills ecosystems, which aim to connect the broad range of employment, skills, economic development and innovation players. Local policy makers could also look for opportunities to promote economic diversification into activities closely related to the existing skills base of a community.

Ensure the employment and skills system targets workers in need: Local employment services could be tailored to support workers most at risk of being affected by automation, while programmes targeting low-skill adults could be expanded. This includes looking at how these programmes can help workers before they face a lay-off to better anticipate labour market change.

Promote a human-centred response to the future of work: Workers’ perspective could be integrated into policy responses, to ensure that policy addresses people’s most pressing needs. Action and co-operation with different social partners can help smooth the transition, while also ensuring that technology enhances worker well-being.

Improve the effectiveness of training for SMEs: Policy makers could encourage SMEs to be aware of their training needs, while raising awareness on existing financial incentives for training and promoting the emergence of employer-led networks around skills development.

Ensure firms make use of available skills: Federal and provincial policy makers could look for opportunities to promote the emergence of high-performance work practices within firms to ensure a better use of skills in the workplace. This could include disseminating good practices among firms, while also developing diagnostic tools to help them identify room for improvement, and promoting knowledge transfer across sectors and places.