The increasing sophistication of technology in the workplace is making some skillsets obsolete while increasing the demand for others. Demand-led training systems are better able to ensure that workers build the skills needed in the local labour market. Ad-hoc initiatives in Ontario have been undertaken to measure and collect data on employers skills needs. As an example, the Conference Board of Canada, a Canadian not-for-profit think tank, conducted the Ontario Employer Skills Survey in 2013 to obtain a clear picture of employers’ skills needs.

A comprehensive employer survey does not seem to be regularly conducted in Canada. As labour market demands rapidly shift, employment and training providers will need to work more closely with employers to understand and respond to these shifts. Previously, at the federal level, a Workplace and Employee Survey had been in place to examine the way in which employers and their employees respond to the changing competitive and technological environment. Such a survey could be re-visited. The need for collecting information on employers skills needs becomes even more crucial today, as the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is likely to heavily affect employers needs and skills demand going forward.

In Ontario, the employment and training system has recently experimented with innovative initiatives to prepare people for the future of work that could potentially be scaled up. For example, the SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot funds partnerships that connect employers with the employment and training services needed to recruit workers with the right skills. It also supports job seekers to get into jobs by providing them with sector-specific services. Ontario has also tested the feasibility of a career pathways approach, focusing on building the academic and workplace skills that learners need for entry-level positions within demand sectors, while also providing a bridge to more advanced college credentials and employment opportunities. There is a clear opportunity to assess the success of these initiatives and determine the feasibility of scaling them up across the province.

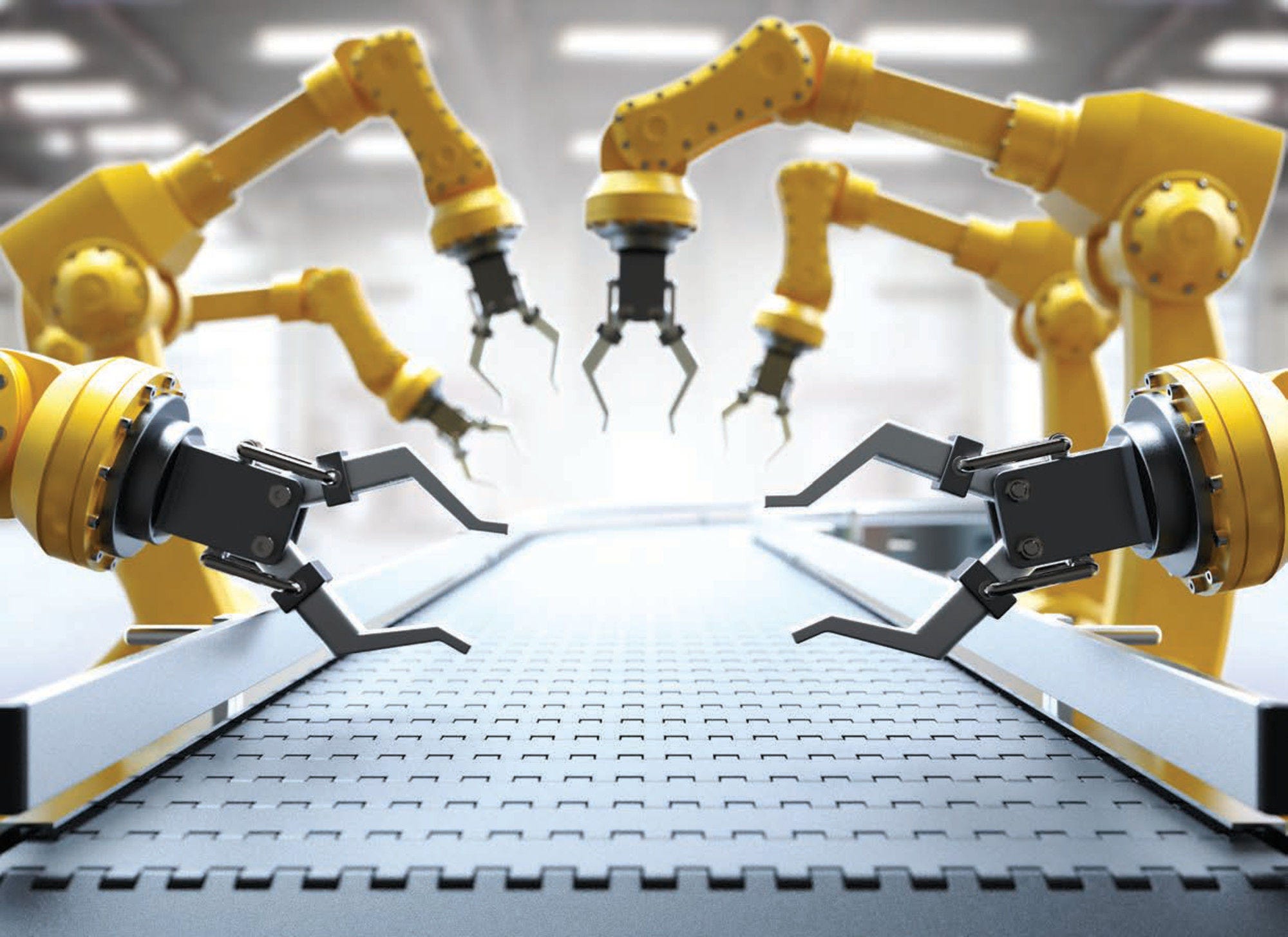

Across the OECD, there is renewed interest in the role of industrial policy to strengthen relevant sectors of the local economy. The tradable sector – which includes all those economic sectors that produce goods or services that can be traded across regions and international borders – is recognised as a driver of productivity growth. Jobs in this sector, however, typically face a higher risk of automation, as they often entail routine and repetitive tasks. This is mostly due to the fact that the tradable sector includes many economic sectors that have an especially high risk of automation, such as agriculture and manufacturing. However, tradable services, which form a small but growing part of the tradable sector, are most likely at much lower risk of automation. Policy makers need to embrace the long-term benefits from shifting towards the tradable sector as productivity growth can lead to better wages and standards of living, while also addressing the risks related to automation that come from this shift. In the context of the future of work, policies can look within the tradable sector and identify how to steer support towards occupations with tasks that are less vulnerable to automation. Given that industrial and skills development policies often pertain to different government departments, policy co-ordination is crucial.

Local skills ecosystems can be instrumental in providing access to relevant specialised knowledge and skills. There may be benefits to be generated by focusing on clusters of expertise as well as regional strengths through a local skills ecosystem approach with the goal of creating a diversified labour market. Local skills ecosystems have a high level of social capital and strong multi-sector linkages between employment services, training organisations, as well as economic development actors, providing local firms with easy access to specialised support to innovate into new activities. Local skills ecosystems can emerge organically and in some cases governments can play a role in providing incentives for their development. The establishment of a local skills ecosystem is often dependent on a strong anchor institution, such as a higher education or vocational education institution as well as a catalyst for change (e.g. evidence suggesting that the region is likely to experience significant adjustment as a result of automation).

Building on local skills ecosystems, policies could promote diversification into activities that are closely related and connected to the existing skills base of the population. As communities respond to structural adjustments resulting from automation, evidence suggests that local networks connecting industries with overlapping skill requirements are predictive of where firms are most likely to diversify economic activities. A successful example of this diversification approach can be found in Akron, Ohio, United States, which was the location of four major tire companies in the 1990s. After experiencing major economic and jobs decline in this activity, the city invested in polymer technology, establishing a National Polymer Innovation Centre, which has since been a new source of job creation in the city. The city has managed to leverage the existing skills base and local knowledge and applied it to new technology and production processes. “Smart Specialisation” strategies within Europe could also provide useful examples for Canada. They generally aim to focus local development activities in areas where there is a critical mass of knowledge and innovation potential.