Job markets are becoming increasingly polarised across the OECD as the employment share of middle-skill jobs has decreased, replaced by increases in the shares of either low or high-skill jobs. Communities in Canada are experiencing different job polarisation transitions, but the majority of regions are clearly shifting towards high-skill jobs. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, labour and skills shortages had been identified as significant labour market challenges in Canada. The ongoing crisis risks exacerbating these gaps, as workers across industries will have to adapt to rapidly changing conditions, and firms will have to learn how to match workers to new roles and activities. The pandemic is also making worker access to training and skills development and the use of skills in the workplace more important than ever. This chapter analyses how the demand and supply of skills is changing at the local level across Canada, with a special focus on the Province of Ontario.

Preparing for the Future of Work in Canada

3. Job polarisation and changing skills needs at the local level in Canada

Abstract

In Brief

Labour markets have become increasingly polarised in Canada over the past two decades, as across most OECD countries, witnessing a decline in the employment share of middle-skill/middle-pay jobs. Looking at the period 1995-2015, Canada experienced a similar degree of polarisation as the United States, with increases in the shares of low- and high-skill jobs. However, over 1998-2018, Canada saw a slight decline in the share of employment in low-skill jobs.

Between 2011 and 2018, all provinces in Canada have experienced a clear shift in employment shares towards high-skill jobs, but differences in job polarisation exist within provinces. For example, in Ontario, while Kingston-Pembroke has experienced a clear polarisation trend over the last decade, in Muskoka-Kawarthas the employment share of middle-skill jobs increased between 2011 and 2018. The higher concentration of middle-skill jobs in some regions might pose challenges in the longer term, as middle-skill jobs often involve routine and repetitive tasks that could be subject to automation.

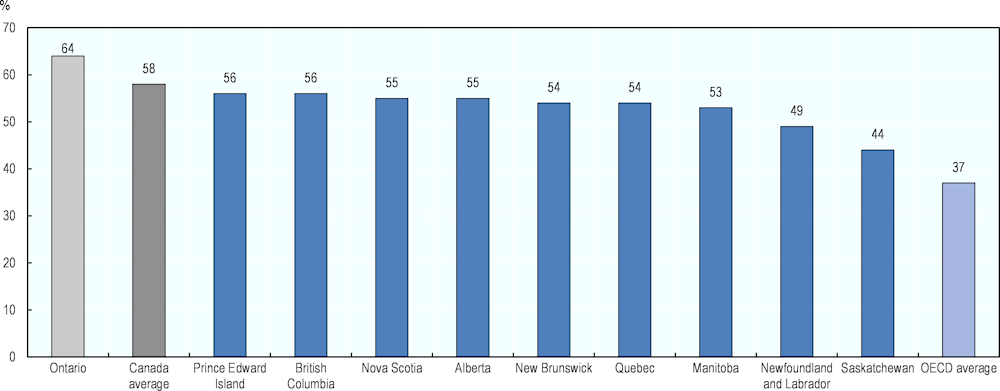

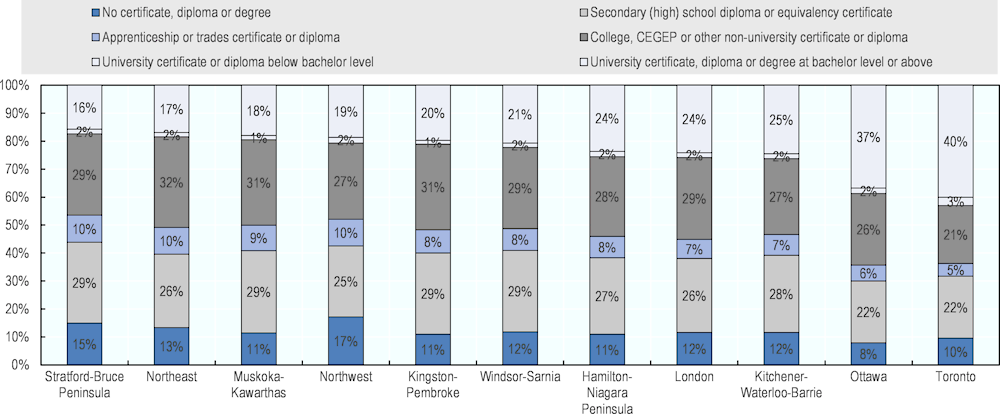

Job polarisation partly reflects increases in the supply of skills across Canada. Canada leads the OECD in terms of educational attainment, with Ontario being the province with the highest share of tertiary graduates, albeit with regional differences. In Toronto and Ottawa, a notable share of the 25-64 aged population holds university certificates (40% and 37% respectively), while less than one in five achieves this level of education in Stratford-Bruce Peninsula (16%), Northeast (17%), Muskoka-Kawarthas (18%) and Northwest (19%).

The increasing sophistication of technology in the workplace is making some skill sets obsolete while increasing the demand for others, and these trends will likely be accelerated by COVID-19. The 2018 ManpowerGroup Talent Shortage Survey reports that skills shortages represent an issue for 41% of employers in Canada. Shortages are affecting some sectors more than others, with manufacturing and retail trade emerging as the sectors suffering the most. COVID-19 is causing labour shortages of some essential workers, while dramatically accelerating the need for workers to have digital skills.

As labour markets face disruption caused by COVID-19, skills development opportunities will be crucial to prepare workers for the upturn and provide them with the skills needed in the future of work. Getting the skills needed to respond to the trends with the future of work will require action on both the skills supply and demand sides. Workers will need to develop a combination of digital and non-digital skills as well as adaptability. Access to training will be crucial especially for vulnerable workers hit hard by the pandemic. At the same time, employers should make better use of the existing workforce skills and invest in the development of their workers’ skills.

Introduction

OECD countries have experienced job polarisation over the past decades - that is a decrease in the employment share of middle-skill jobs and an increase in the share of low- and/or high-skill jobs. Section 3.1 presents trends in job polarisation in Canada and across regions in Ontario. Section 3.2 shows that job polarisation partly reflects increases in educational attainment in Canada. Section 3.3 discusses emerging skills shortages and mismatches across Canada, while section 3.4 presents actions on both the skills supply and demand side that could help reduce mismatches.

3.1. Job polarisation is shifting skills demand in Canada

3.1.1. The share of middle-skill jobs is declining in Canada and the OECD more generally

Labour markets across the OECD have become more polarised over the last decades, with declines in the share of employment in middle-skill jobs relative to jobs with higher or lower skill levels (OECD, 2017[1]). Middle-skill jobs include clerks, craft and related trades workers and machine operators and assemblers. On the other hand, high-skill jobs include professionals, manager and technicians, while low-skill jobs include service workers, shop and market sales workers and elementary occupations. Job polarisation has previously been widely documented by others in the United States (Autor, Katz and Kearney, 2006[2])and Europe (Goos, Manning and Salomons, 2009[3]). For almost all countries for which data is available this has resulted in a shift of employment towards high-skill occupations (OECD, 2019[4]). Looking at the period 1995-2015, Canada experienced a similar degree of polarisation as the United States. However, the decline in oil prices in 2014 resulted in lower demand for workers related to the resource sector. Over 1998-2018, Canada actually saw a slight decline in the share of employment in low-skilled jobs (OECD, 2020[5]).

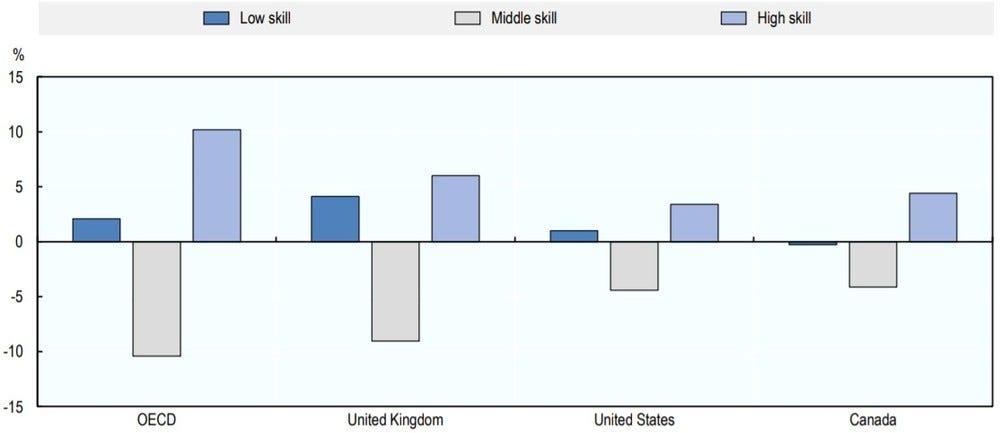

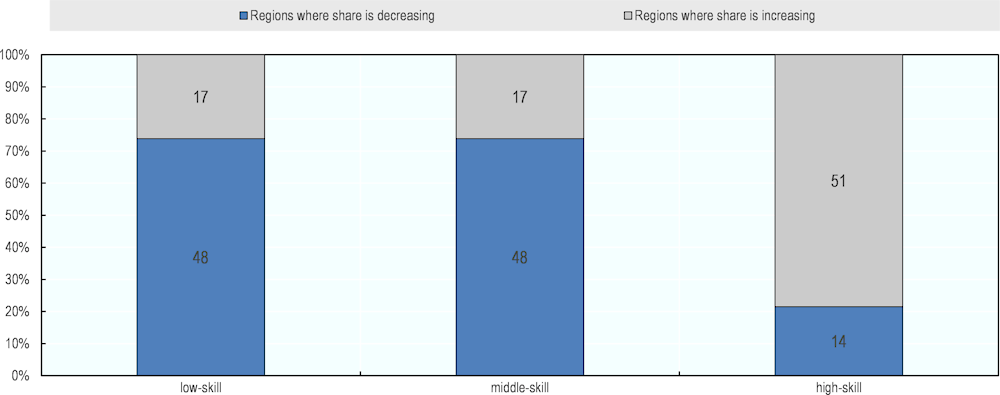

Figure 3.1 illustrates that the share of employment in middle-skill jobs has decreased relative to in high- and low-skill jobs across the OECD over the last two decades.

While high-skill jobs are considered to be complemented by Information and Communication Technology (ICT), middle-skill jobs are typically substitutes. Technological developments and their capacity to replace routine jobs are identified as drivers of job polarisation, as the impact of technology on jobs varies across the skills distribution. Pioneering work looking at the impact of technological change and digitalisation on the tasks performed by workers at their jobs finds that within industries, occupations and education groups, computerisation is linked with reduced labour input of routine manual and routine cognitive tasks. On the other hand, it is associated with increased input of non-routine cognitive tasks (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[6]). Middle-skill jobs, such as clerical and production jobs, typically entail routine tasks and are the ones easier to automate given the current state of technological developments. On the other hand, low-skill jobs tend to involve non-routine manual tasks, for example requiring manual dexterity, which are harder to automate.

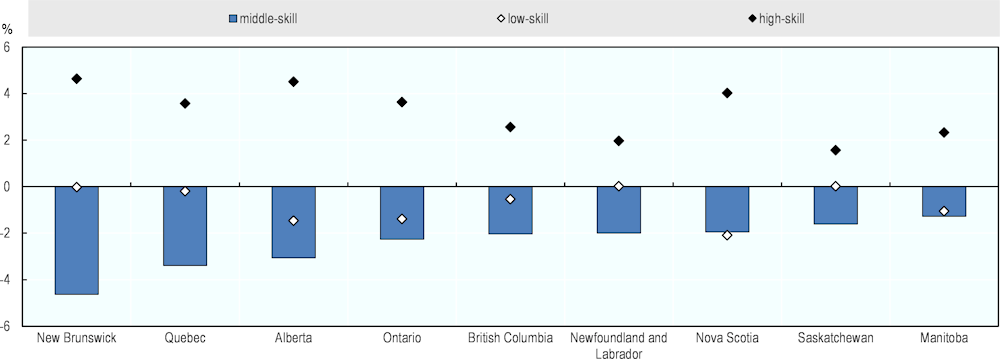

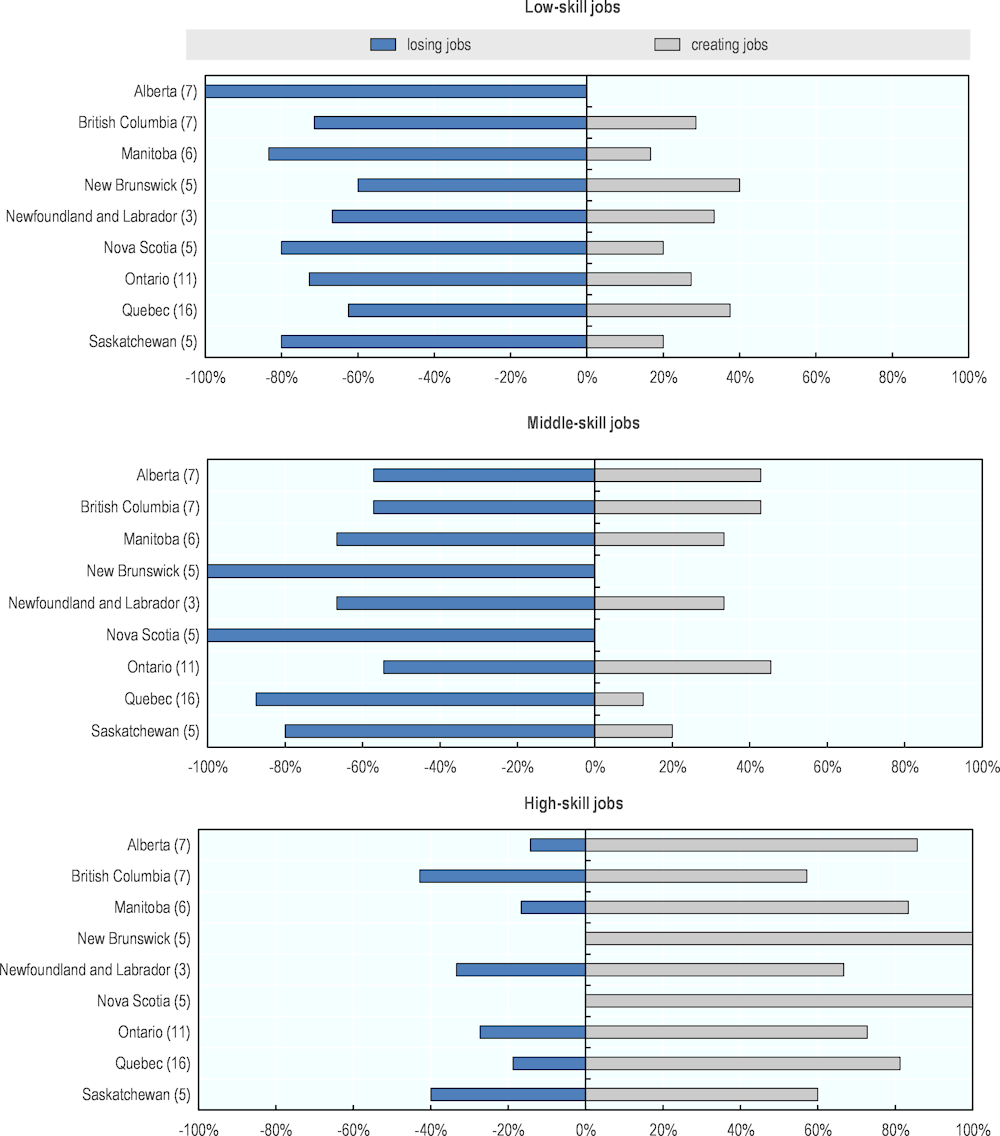

Looking at the 2011-2018 period, the employment share of middle-skill jobs has declined, while there has been a clear shift towards high-skill jobs in all provinces. Between 2011 and 2018, the share of middle-skill jobs has decreased in all of Canada’s provinces (see Figure 3.2). In addition, in all but New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador, the share of low-skill jobs has also decreased, a trend that is particularly evident in provinces such as Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia. New Brunswick has experienced the largest shift in respective shares of total employment, undergoing the largest loss in middle-skill jobs across Canadian provinces in the last 10 years. Meanwhile, in Quebec, Alberta, and Ontario, high-skill jobs have grown to take up a larger part of the labour market since 2011, a trend that is more subdued in British Columbia.

Figure 3.1. Job polarisation has taken place across the OECD

Note: High-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 1, 2, and 3. That is, legislators, senior officials, and managers (group 1), professionals (group 2), and technicians and associate professionals (group 3). Middle-skill occupations include jobs classified under the ISCO-88 major groups 4, 7, and 8. That is, clerks (group 4), craft and related trades workers (group 7), and plant and machine operators and assemblers (group 8). Low-skill occupations include jobs classified under major groups 5 and 9. That is, service workers and shop and market sales workers (group 5), and elementary occupations (group 9). Skilled agricultural and fisheries workers were excluded from this analysis.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en.

Figure 3.2. In all provinces in Canada, the share of middle-skill jobs has decreased and the share of high-skill jobs increased

Note: TL2 regions (excluding Prince Edward Island, Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories & Nunavut).

Source: OECD calculations on Labour Force Surveys.

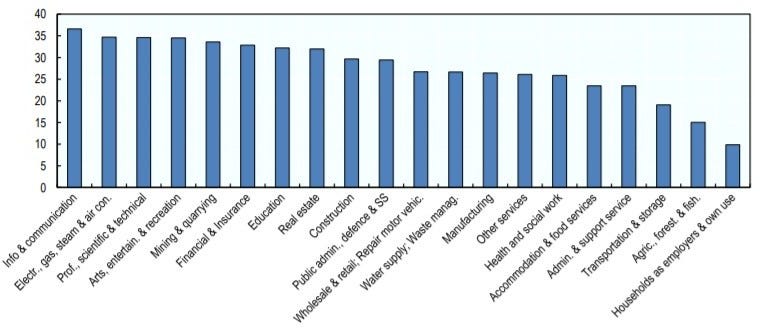

3.1.2. Polarisation is mainly driven by occupational shifts within sectors across the OECD

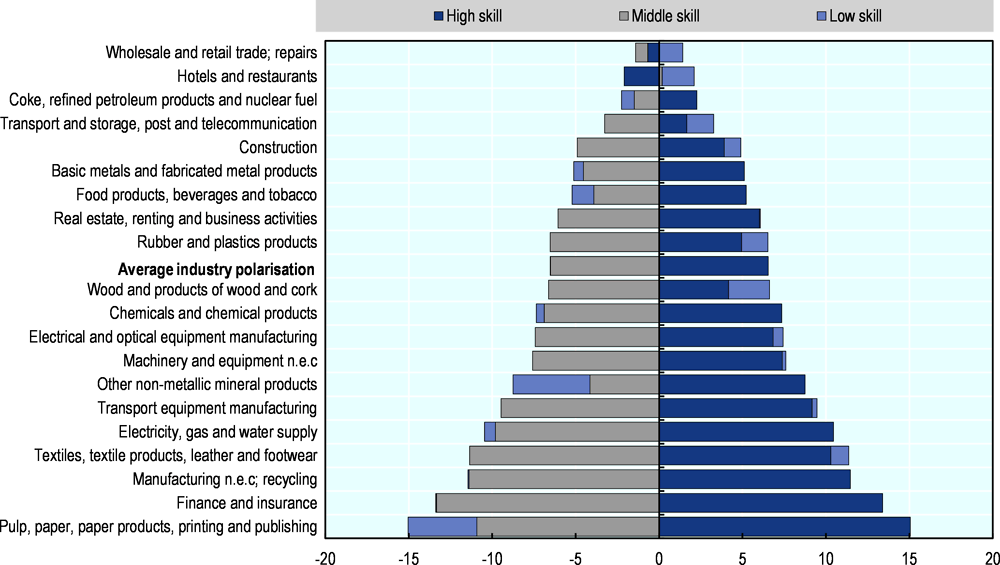

Polarisation across the OECD occurs mostly as a result of occupational changes within individual industries (two-thirds of the change), while the reallocation of employment away from less polarised industries towards more highly polarised industries contributes the other third. The decline in the share of middle-skill occupations in total employment has affected almost all sectors of the economy across OECD countries. In most industries, these declines have been entirely offset by growth in top occupations. This is particularly the case for those sectors where the decline in middle-skill occupations has been the largest across the OECD, including manufacturing industries (such as “Pulp, paper, paper products, printing and publishing”, “Chemicals and chemical products”, and “Transport equipment manufacturing”), and services (such as “Finance and insurance”, and “Real estate and business services”). Two services industries have experienced a clear shift of employment towards the bottom of the skill distribution (“Hotels and restaurants” and “Wholesale and retail trade; repairs”) (OECD, 2017[1]).

The continued shift of employment from manufacturing to services accounts for the remaining one-third of job polarisation across the OECD (OECD, 2017[1]). Services jobs tend to be divided between high-skill professional and managerial jobs that require non-routine cognitive skills on one side, and low-skill jobs that require non-routine manual skills on the other (Goos and Manning, 2007[7]). Manufacturing instead provides more opportunities for middle-skill workers performing routine tasks. Routine exposures are highest in industries where core tasks follow “precise, well-understood procedures” (Acemoglu and Autor, 2010[8]), such as manufacturing, financial services, and transportation and storage. This reflects that these industries have traditionally had high concentrations of occupations with high routine tasks. For example, machine operators are pervasive in manufacturing; financial services have historically drawn on clerical workers (e.g. for data entry and accounting); and transportation and storage employs both elementary workers for manual labour, as well as clerical workers for logistics and communications (Das and Hilgenstock, 2018[9]).

Figure 3.3. Polarisation has taken place within many industries across the OECD

Source: OECD (2017[1]), OECD Employment Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2017-en.

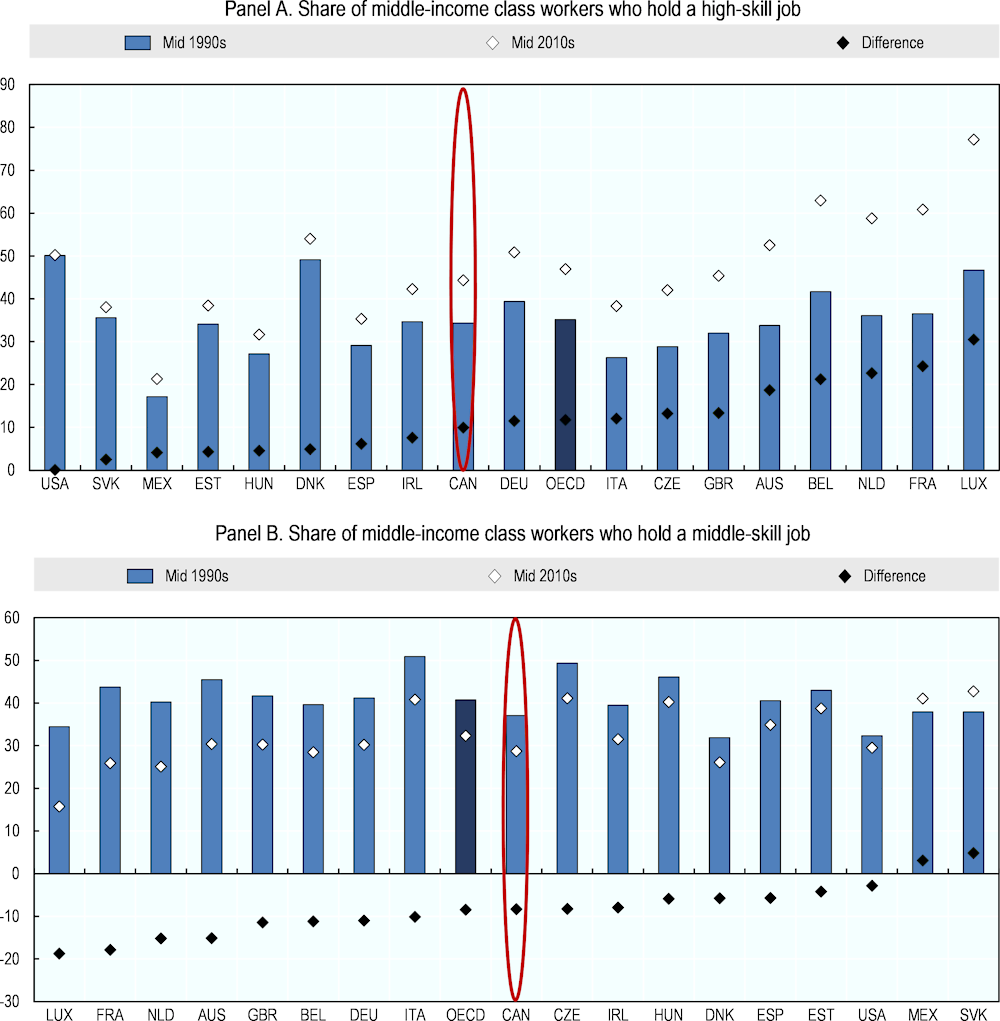

3.1.3. Middle income workers are increasingly highly-skilled in Canada

Concerns around job polarisation are part of more general public concerns around growing inequalities and a shrinking share of workers attaining middle income. Middle-skill jobs were once considered a reliable ticket to a middle-class lifestyle, and even a springboard for social mobility for the next generation. However, recent research from the OECD suggests that this question is more complicated than a one-to-one relationship between a decline in middle-skill jobs and a shrinking middle class. In OECD countries, growth in high-skill occupations has outpaced growth in middle- and low-skill occupations, shifting the overall labour market distribution towards higher-skill jobs. The changing relationship between skills and income classes means that middle-skill workers are now more likely to be in lower-income classes than middle-income classes. The wage structure is also characterised by growing divides between top earners and everyone else, rather than growth at both ends of the wage scale (OECD, 2019[10]).

In Canada, the share of workers attaining middle income has declined by about 4% from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s. On the other hand, the share of workers belonging to lower income levels has increased by about 5% and the share of those belonging to higher income has slightly decreased. Canada therefore belongs to a group of OECD countries that have witnessed a decline in the share of workers attaining middle income, but contrary to most countries in the same group, Canada has been characterised by a clear shift towards lower income levels (OECD, 2019[11]).

Middle-income workers are increasingly highly skilled and less middle-skilled. High-skill workers now outnumber the middle-skill in the middle-income class, in Canada as across most OECD countries (OECD, 2019[10]). In addition, the share of middle- and low-skill workers in low income has increased, while fewer medium- and low-skill workers achieve middle or upper income level. Similarly, the share of high-skill workers achieving upper and middle-income has decreased over the mid-1990s/mid-2010s period in Canada. At the same time, there has been an increase in the share of high-skill workers in low income classes (OECD, 2019[11]).

Figure 3.4. Middle-income workers are increasingly highly skilled and less middle-skilled

Note: The middle-income class comprises all individuals in households with net disposable income between 75% and 200% of the median household income in a given year and country. The income of reference is the household disposable income, corrected for household size with the OECD equivalence scale.

Source: OECD (2019[10]), Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/689afed1-en.

3.1.4. In most Canadian regions, the employment share of middle-skill jobs is declining, but differences exist

The large majority of economic regions across Canada are experiencing declines in the employment share of middle-skill jobs (48 regions) and low-skill jobs (48 regions), and most regions are witnessing increases in the share of high-skill jobs (51 regions) (see Figure 3.5). However, the provincial job polarisation picture hides marked disparities among regions in Canada. In about 17 regions across Canada, the share of middle-skill jobs over total employment is increasing. As discussed in Chapter 1 of this OECD report, middle-skill jobs typically involve repetitive and routine tasks, which face a higher risk of being affected by automation. Northeast in British Columbia is the region that has witnessed the largest increase in the share of middle-skill jobs, which have increased by 14.9 percentage points as a share of total employment between 2011 and 2018. Middle-skill jobs have also increased by several percentage points in North Coast and Nechako in British Columbia (5.6 p.p.), Maurice in Quebec (5.1 p.p.) and Muskoka-Kawarthas in Ontario (3.6 p.p.) over the same period.

Disparities in job polarisation trends are more accentuated within some provinces (see Annex 3.A). In Alberta, all regions have lost low-skill jobs, while in other provinces the picture is mixed. For example, two out of five regions in New Brunswick and six out of sixteen regions in British Columbia have increased their employment shares in low-skill jobs. Regional disparities are even more pronounced in middle-skill jobs dynamics. In New Brunswick and Nova Scotia all regions have lost middle-skill jobs as a share of total employment, while almost half of the regions in Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario have experienced increases in the share of middle-skill jobs. The share of high-skill jobs has increased in most regions within provinces. Regional disparities in high-skill jobs are more visible in British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Saskatchewan.

Figure 3.5. In most regions in Canada, the employment share of middle-skill and low-skill jobs is declining, while the share of high-skill jobs is increasing

Note: Numbers in the bars denote the number of economic regions.

Source: OECD calculations on Labour Force Surveys.

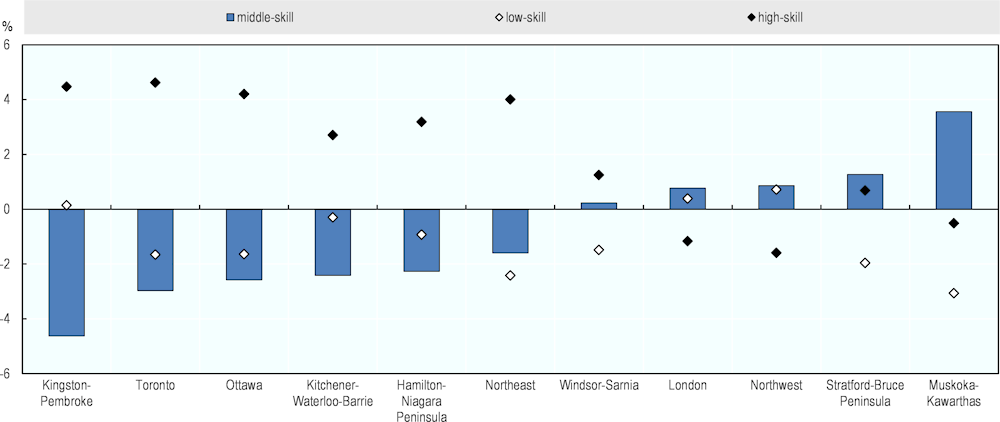

Regional differences in job polarisation dynamics have also emerged in Ontario (see Figure 3.6). Kingston-Pembroke, Toronto and Ottawa have witnessed a substantial increase in the share of high-skill jobs and a steep decrease in that of middle-skill jobs. Similar dynamics have emerged in Kitchener-Waterloo-Barrie, Hamilton-Niagara Peninsula and Northeast. On the other hand, high-skill jobs have decreased as a share of total employment in Muskoka-Kawarthas, Northwest and London. Muskoka-Kawarthas has experienced a substantial increase in the share of middle-skill jobs over total employment. Stratford-Bruce Peninsula, Northwest, London and Windsor-Sarnia have also experienced increases in the share of middle-skill jobs.

Figure 3.6. Job polarisation across regions in Ontario

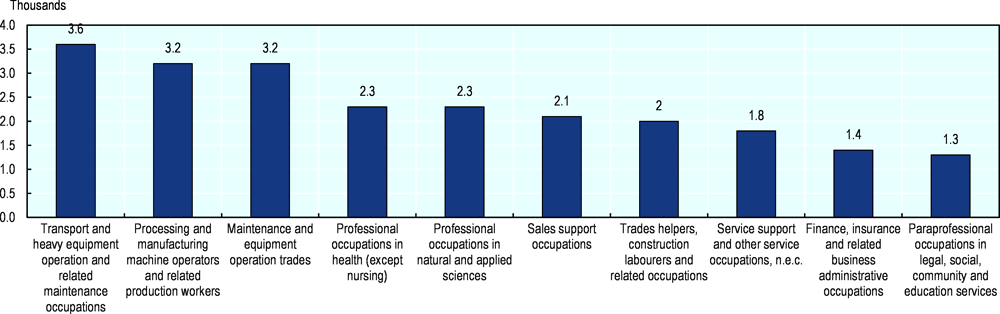

Box 3.1. Spotlight on London: an increasing demand for middle-skill jobs

London is among the regions in Ontario that have experienced an increase in the share of middle-skill jobs over 2011-2018. Wholesale and retail trade is the main sector of employment in the region, accounting for 16.1% of total employment in 2018. Manufacturing employment is among the highest across regions in Ontario, standing at 15% in the same year. Increases in the share of middle-skill jobs reflect a growing demand for middle-skill occupations in the region, which typically include skilled trade occupations. Considering the 2011-18 timeframe, transport and heavy equipment operation have created most new jobs (3 600). Jobs in processing and manufacturing machine operators as well as maintenance and equipment operation trades have also increased (3 200 new jobs each).

In addition, the demand for middle-skill workers such as trades workers is growing in London. It is estimated that in the London-area economy, most in-demand jobs are in the retail and service sectors, which are often low-paying. When it comes to well-paid jobs without enough people, skilled trades are at the top. Across Ontario, one in three tradespeople are older than 55, and 20% of Ontario jobs will be skilled trades-related in the next five years. Shortages have been accompanied by increases in the working age population reporting to be “not in the labour force”, which amounted to 227 300 people in December 2018. The Ontario government is tackling these challenges by supporting pre-apprenticeship projects that will prepare people in London for good jobs and careers. The Ontario government is investing in four London-based training programmes for a variety of trades, including baker-confectioner, construction worker, brick and stone mason and educational assistant. Pre-apprenticeship training promotes careers in the trades as an option for all Ontario residents, including youth at risk, new Canadians, women and Indigenous people. The training programmes are free, last up to one year and often combine classroom training with an 8-12 week work placement.

Figure 3.7. What are the 10 occupations that have created most jobs in London?

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0312-01 Employment by economic regions and occupation, annual (x 1,000). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/1410031201-eng; Government of Ontario (2020[12]), Ontario Preparing People in London for Jobs, https://news.ontario.ca/mol/en/2020/01/ontario-preparing-people-in-london-for-jobs.html (accessed on 26 February 2020); The London Free Press (2020[13]), Begging for bodies: These are London’s most in-demand jobs, trades, https://lfpress.com/news/local-news/begging-for-bodies-welders-and-machinists-among-londons-most-wanted-trades (accessed on 26 February 2020); worktrends.ca (n.d.[14]), Labour Market Facts for the London Economic Region - Interactive Tool, https://www.worktrends.ca/categories/london-economic-region (accessed on 26 February 2020).

3.2. Job polarisation partly reflects increases in the supply of skills in Canada

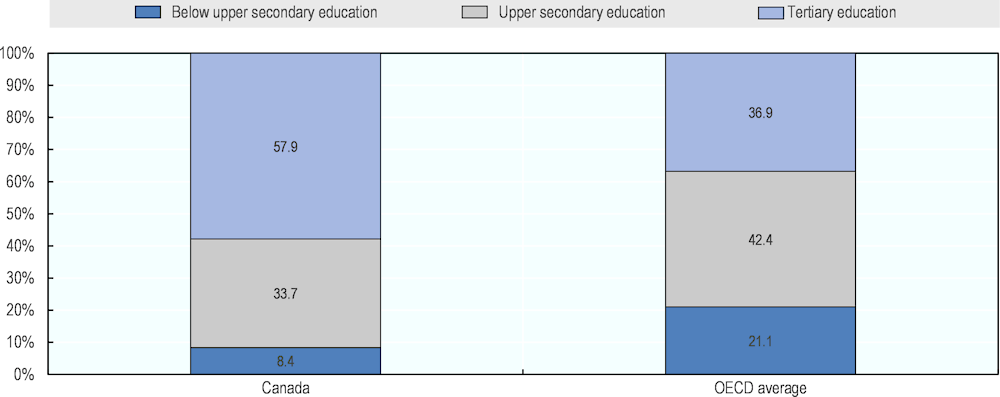

3.2.1. Canada outperforms OECD countries in educational attainment

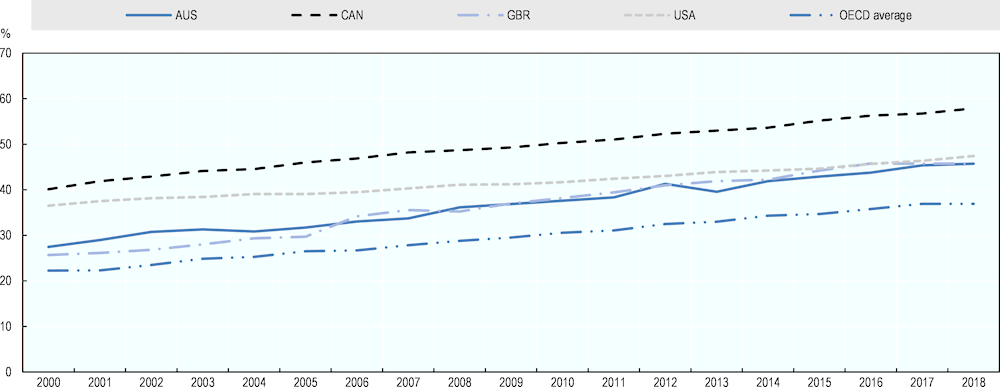

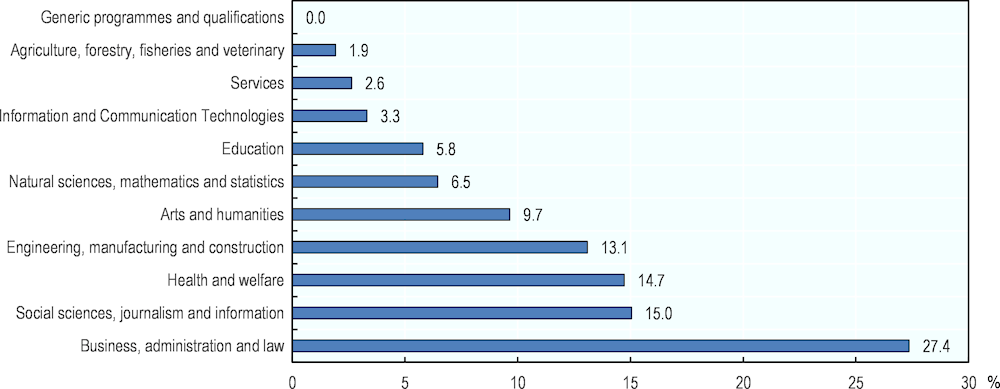

The changes in the choice of occupational training in developed countries show that educational upgrading is a mechanism through which economies move away from learning routine cognitive tasks and manual tasks and towards learning non-routine cognitive and interactive tasks (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[15]). Adults achieve higher levels of education in Canada than on average across the OECD (see Figure 3.8). About 57.9% of the 25-64 year-old population achieved tertiary education in 2018 in Canada, compared to 36.9% for the OECD average. Only 8.4% of the Canadian adult population attained only below upper secondary education in 2018 and 33.7% attained upper secondary education, compared to 21.1% and 42.4% for the OECD average. In addition, the supply of skills has been steadily expanding over the last decades in Canada. The share of tertiary educated adults has been consistently above the OECD average and OECD high-performing countries for decades (see Figure 3.9). Considering 2000 for example, already 40.1% of the Canadian population aged more than 25 attained tertiary education, compared to 22.3% on average across the OECD. Most tertiary education graduates mainly chose business administration and law, health and welfare as their fields of study, while few tertiary students choose services, agriculture and ICT as their specialisation (see Figure 3.10). Business administration and law are the main field chosen by tertiary education graduates across most OECD countries.

Colleges play an important role in preparing students for the labour market in Canada. A significant share of the Canadian population has college degrees, including both community colleges and polytechnics. Many community colleges and polytechnics in Canada offer both ISCED 5 (short-cycle tertiary) and ISCED 4 (post-secondary non-tertiary) programmes, including occupational preparation and adult education programmes. About 10.5% of Canadians hold post-secondary non-tertiary education and 26.1% hold short-cycle tertiary education, compared to 5.8% and 7.3% respectively for the OECD average in 2018.

The share of tertiary educated younger adults who have obtained a master’s or a doctoral degree is below the OECD average. About 26% and 22% of 25-64 year-olds held short-cycle tertiary education and a Bachelor’s or equivalent as their highest educational attainment in 2018, compared to the OECD averages of 7% and 17%. Only 10% have completed a master’s or equivalent, compared to the OECD average of 13% (OECD, 2019[16]) .

Figure 3.8. Canada attains higher levels of tertiary education than on average across the OECD

Source: OECD (2019), Adult education level (indicator). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/36bce3fe-en (Accessed on 13 May 2020).

Figure 3.9. Adult education levels have been on the rise across Canada and the OECD

Source: OECD (2019), Adult education level (indicator). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/36bce3fe-en (Accessed on 17 July 2019).

Figure 3.10. Most tertiary education graduates in Canada have chosen business, administration and law as their field of study

Source: OECD (2019), Education and a Glance database.

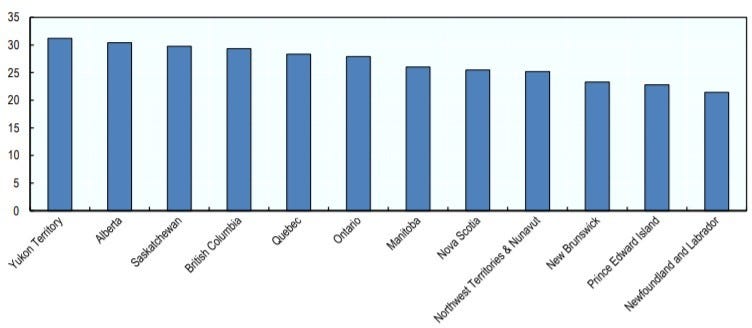

3.2.2. Educational attainment is higher in Ontario than on average in Canada

Ontario performs better than the OECD and the Canadian averages in terms of educational attainment, with 64% of the working age population holding tertiary education in 2018 (see Figure 3.11). In British Columbia and Quebec 56% and 54% of the working age population holds tertiary education. The skills composition of the workforce varies in Canada, with some provinces, such as Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan, where less than 50% of the population attains tertiary education.

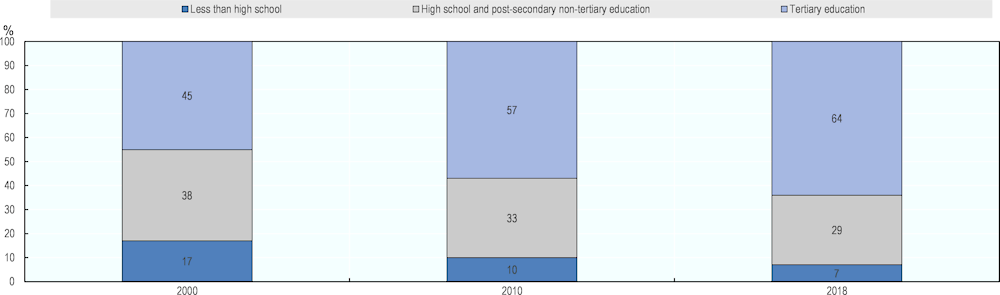

The educational composition of the Ontario workforce has changed since the 2000s, with substantial increases in tertiary education attainment (see Figure 3.12). In 2000, almost 40% of the working age population attained high school and post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest level of education, slightly below the share of those achieving tertiary education. At the same time, almost one in five in Ontario attained less than high school education in 2000. Over the recent decades the shares of working age people attaining high school or less has substantially decreased.

Figure 3.11. Tertiary education attainment is higher in Ontario than in other Canadian provinces and the OECD

Note: Data does not include the territories.

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 37-10-0130-01 Educational attainment of the population aged 25 to 64, by age group and sex, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada, provinces and territories, https://doi.org/10.25318/3710013001-eng.

Figure 3.12. The educational composition of the Ontario workforce has changed over time

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 37-10-0130-01 Educational attainment of the population aged 25 to 64, by age group and sex, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada, provinces and territories, https://doi.org/10.25318/3710013001-eng.

3.2.3. The population in large urban centres holds higher levels of education in Ontario

While educational attainment has been consistently growing in Ontario, regions within the province achieve different levels of education (see Figure 3.13). In Toronto and Ottawa, the large majority of the 25-64-aged population have university certificates, diplomas or degrees at bachelor level or above (40% and 37% respectively). On the other hand, less than one person in five holds this level of education in Stratford-Bruce Peninsula (16%), Northeast (17%), Muskoka-Kawarthas (18%) and Northwest (19%). In Northwest and Stratford-Bruce Peninsula, more than 15% of people have no certificate, diploma or degree. The share of people attaining secondary education reaches almost 30% in Kingston-Pembroke, Muskoka-Kawarthas and Windsor-Sarnia. An element contributing to regional differences in educational attainment could be the fact that young people might move to Toronto and Ottawa to pursue studies, and remain there after finding jobs that fit their skills, which are more likely to be available where they went to school and in urban centres in general.

Among the 25-64 years olds holding post-secondary certificates, diplomas or degrees, most have degrees in business, management and public administration, architecture and engineering and health and related fields in Ontario, with some regional differences reflecting sectoral employment. The highest shares of 25-64 year-olds holding business, management and public administration degrees is found in Toronto and Ottawa (about 25% and 20% respectively), reflecting the availability of jobs in business services and public administration. In Kingston-Pembroke, the share of graduates with post-secondary certificates in health and related fields is higher than in other Ontario regions, which partly reflects the region’s higher employment shares in the health field.

Figure 3.13. Largest urban areas have the highest share of university diplomas in Ontario

Source: OECD calculations on 2016 Census.

3.3. Canada is experiencing labour and skills shortages, which risk being exacerbated by COVID-19

3.3.1. Employers report labour shortages across Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak is likely to have lasting effects on the demand for labour in Canada as around the world. It has been suggested that the pandemic crisis could cause labour shortages in essential services and affect infrastructure in Canada (Tunney, 2020[17]). The agriculture sector is also reported to be experiencing labour shortages, as COVID-19 has led to delays in arrivals of temporary foreign workers, that the industry relies on (Sheldon, 2020[18]).

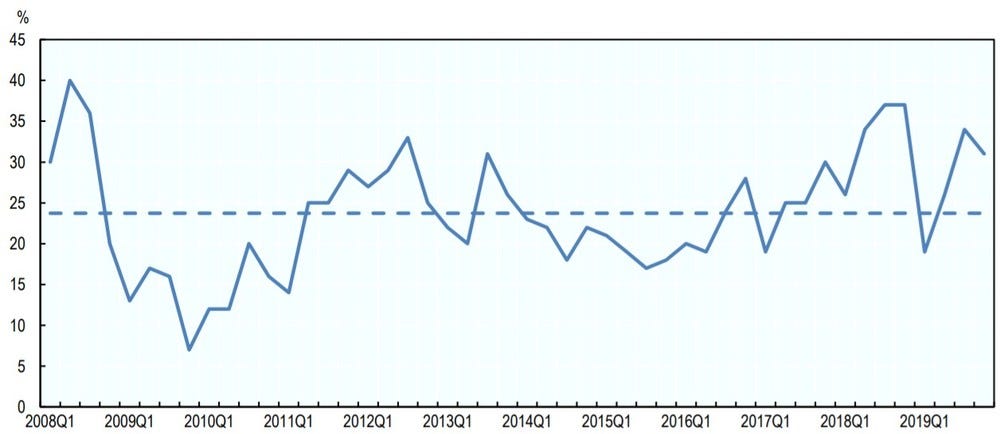

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Canada was already facing labour shortages, as many employers struggled to fill open positions. Strong demand for workers is evident from the share of firms who report labour shortages that restrict their ability to meet demand. At 31%, this share is above the historical average (see Figure 3.14). The job vacancy rate, accounting for unfilled vacancies as a share of total occupied and vacant jobs, reached 3.5% in Q2 2019, reflecting tightening labour market conditions in Canada since 2016, when the rate stood at 2.4%. From a survey of about a hundred firms undertaken by the Bank of Canada to gather economic and business perspectives and sentiments for monitoring purposes, workforce ageing, changing worker preferences and difficulties attracting workers in rural areas were pointed out as main perceived challenges (Bank of Canada, 2019[19]). According to a survey by the Business Development Bank of Canada, 53% of small-and medium-sized enterprises say labour shortages will cause them to limit business investment (Matti, 2019[20]).

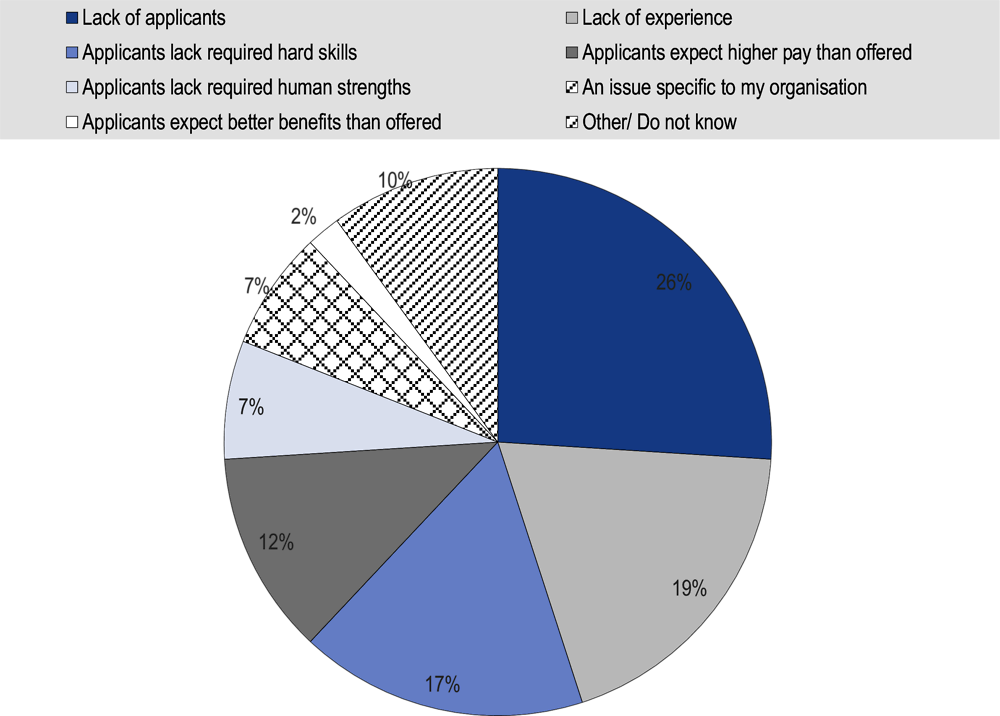

More than one in four employers in Canada report that the lack of applicants is the main reason why they cannot fill a position, according to the 2018 ManpowerGroup Talent Shortage Survey. The survey reports that shortages represent an issue for 41% of employers in Canada, and these are particularly challenging for large firms, who face twice as much difficulty filling roles than smaller ones (58% and 26% respectively). The share of companies reporting shortages in Canada is lower than the global average in 2018 (45%), and consistently below over the last decade. However, it has been increasing over the last years, suggesting that more and more companies are facing challenges filling positions in Canada. The lack of experience and of hard skills, as well as applicants expecting higher pay than offered are commonly cited reasons leading to shortage in Canada, reported by 19%, 17% and 12% of employers respectively (ManpowerGroup, 2018[21]).

Figure 3.14. A large share of firms reported labour shortages in Canada before COVID-19

Note: The dotted line represents the historical average since 2008Q1.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en; Bank of Canada (2019[19]), Business Outlook Survey—Autumn 2019, https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2019/10/business-outlook-survey-autumn-2019/ (accessed on 23 January 2020).

Figure 3.15. The lack of applicants is the main reason employers cannot fill positions in Canada

Source: ManpowerGroup (2018[21]), 2018 Talent Shortage - Solving the Talent Shortage: Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge, https://manpowergroup.ca/campaigns/manpowergroup/talent-shortage/pdf/canada-english-talent-shortage-report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2019).

3.3.2. Labour shortages are particularly critical in middle-skill occupations across Canada

Despite drops in employment shares linked to job polarisation, middle-skill jobs top the list when it comes to labour shortages in Canada. These include skilled trade occupations (e.g. electricians, welders and mechanics), sales representatives and drivers. Together with engineers and technicians, these occupations have consistently ranked among the top five hardest roles to fill in Canada for the past ten years (ManpowerGroup, 2018[21]). Consumerism drives demand for drivers and customer services representatives, while online retail activity continues to rise rapidly, together with jobs in logistics and last-mile delivery. Shortages in elementary occupations tend to be particularly accentuated in regions with rapid economic growth, historically in the mining or oil and gas industries (Komarnicki, 2012[22]). These are also the regions where the cost of living tends to be higher, and workers are therefore discouraged from moving there.

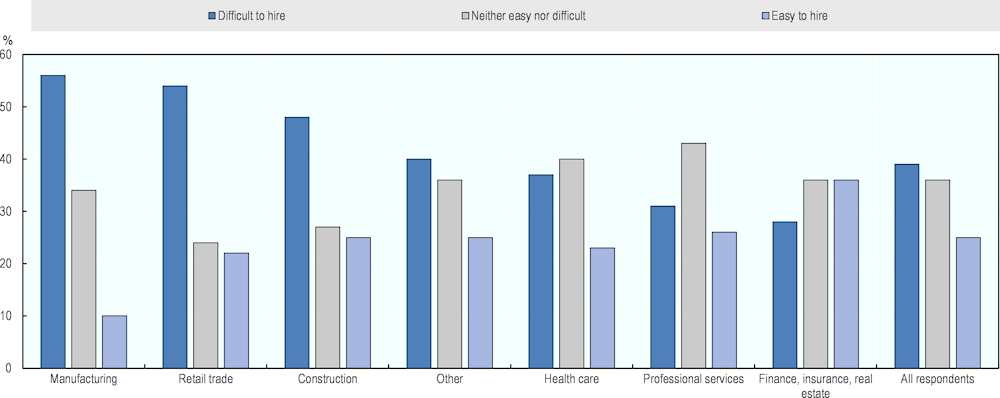

Labour shortages prevail in those sectors that typically face a higher risk of automation. Surveys undertaken with more than a thousand Canadian entrepreneurs by Business Development Canada show that manufacturing and retail trade are the sectors where the largest share of companies report difficulties in hiring (56% and 54% respectively) (Business Development Bank of Canada, 2018[23]). These sectors are followed by construction, health care, professional services and finance, insurance and real estate (see Figure 3.16). This could be linked to several factors, including insufficient participation in Vocational Education and Training (VET), relatively poorer pay and working conditions in some sectors. Automation and new technologies could represent an opportunity to tackle shortages and boost productivity in sectors at high risk of automation facing shortages, such as manufacturing and retail trade.

Figure 3.16. Labour shortages are mostly felt in manufacturing and retail trade across Canada

Note: Maru/Matchbox survey on Canada’s labour shortage, 2018. Results exclude respondents who said, “I don’t know” or “I prefer not to answer.” Results are weighted by region and company size to reflect Canada’s economy more accurately. n = 1 067.

Source: Business Development Bank of Canada (2018[23]), Labour Shortage in Canada: Here to stay, https://www.bdc.ca/en/documents/analysis_research/labour-shortage.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2020).

3.3.3. In addition, many workers lack the skills needed in the labour market in Canada

The mismatch between the supply and demand for skills may be exacerbated with the more rapid pace of change in the future of work. Mismatches can take the shape of skills shortages, when adequate skills are hard to find, or that of skill surpluses, when certain skills are in excess relative to the demand in the labour market. Skills mismatch can have a negative impact on productivity. Research for Canada shows that the impact of technological change and automation will mainly affect those with lower education level, and that individuals with a broad set of skills will be best-equipped to succeed in an era of increasing uncertainty and labour market changes (Morneau Shepell and Business Council of Canada, 2018[24]).

Changes related to digitalisation and automation have the potential to boost productivity, but they will also require workers to get new skills. Employer surveys conducted by Morneau Shepell and Business Council of Canada in 2017 look at how companies in Canada are adapting to changes in the demand for skills. The survey engaged 95 large Canadian private-sector employers, employing a total of more than 850 000 workers across Canada, specifically looking into the consequences for hiring practices linked to automation and technological developments. While hiring managers generally had a positive view of the impact of artificial intelligence and automation on the size of their workforce, they still cautioned that fast changes increase uncertainty in predicting longer-term trends. Companies also place higher expectations on new graduates, who need to be adaptable and able to acquire a mixed set of skills, and new partnerships are unfolding between businesses and education institutions to build work-integrated learning programmes (Morneau Shepell and Business Council of Canada, 2018[24]).

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is also likely to make some skills more relevant in the future. COVID-19 has changed not only how people work but also how they consume, as well as basic patterns of movement and travel. The crisis has accelerated the levels of digitalisation to help reduce avoidable physical interactions. This has meant finding ways to reinvent work and, in some cases, a partial disruption of jobs and changes in the way workers perform them. The pandemic is setting up what could be lasting employment shifts that could require the large-scale re-skilling of workers. It is suggested that it will be crucial for employees to develop digital, higher cognitive, social and emotional, and adaptability and resilience in a post-COVID labour market (McKinsey & Company, 2020[25]).

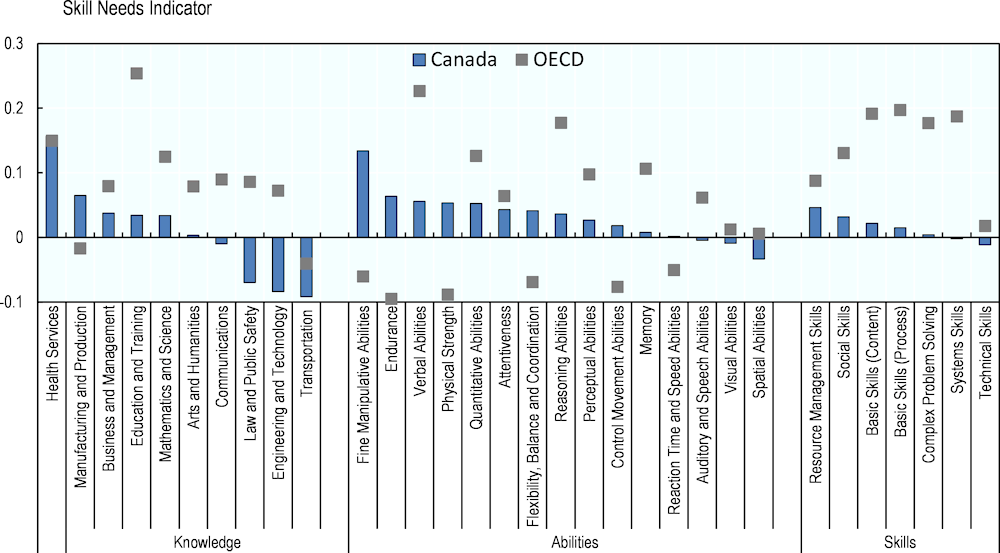

The OECD Skills for Jobs database shows that some knowledge, abilities and skills are in shortage in Canada. The database defines skills as either hard-to-find (in shortage) or easy-to-find (in surplus) (see Box 3.2 for more information on the database). Skills shortages emerge when employers are unable to recruit staff with the necessary set skills in the accessible labour market and at the going rate of pay and working conditions. Skill surpluses arise in the opposite case, when the supply exceeds the demand for a given skill. The database also looks at the abilities and knowledge areas in shortage. Health services, fine manipulative abilities and resource management skills emerge respectively as the knowledge, abilities and skills most in shortage in Canada.

Box 3.2. Measuring skills mismatches through the OECD Skills for Jobs database

The OECD Skills for Jobs Database provides country-level (as well as subnational) information on shortages and surpluses of a wide range of dimensions, including cognitive, social and physical skills. Information is disaggregated into more than 150 job-specific Knowledge, Skills and Abilities and is available for 40 countries among OECD and emerging economies. Knowledge areas refer to the body of information that makes adequate performance of the job possible (e.g. knowledge of plumbing for a plumber; knowledge of mathematics for an economist). Skills refer to the proficient manual, verbal or mental manipulation of data or things (e.g. complex problem solving; social skills). Abilities refer to the competence to perform an observable activity (e.g. ability to plan and organise work; attentiveness; endurance).

Source: OECD (2018[26]), Skills for Jobs, https://www.oecdskillsforjobsdatabase.org/data/Skills%20SfJ_PDF%20for%20WEBSITE%20final.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

Figure 3.17. Skills mismatches in Canada and the OECD

Note: Positive values indicate shortages while negative values indicate surpluses. The indicator is a composite of five sub-indices: wage growth, employment growth, growth in hours worked, unemployment rate and growth in under-qualification.

Source: OECD Skills for Jobs database (www.oecdskillsforjobsdatabase.org).

3.3.4. Skills shortages are affecting Ontario’s labour market

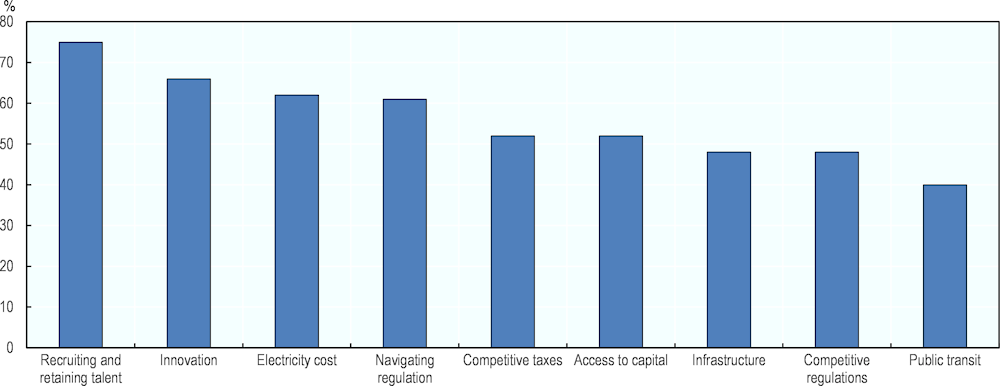

Skills shortages are having profound impacts on Ontario’s labour market. In 2013, it was estimated that skills shortages would cost the provincial economy about 4% of provincial GDP and they were projected to get worse without action to address them (The Conference Board of Canada, 2013[27]). The 2019 Business Confidence Survey, conducted by the Ontario Chamber of Commerce, shows that for 75% of members the ability to recruit and retain talent is a critical factor to organisational competitiveness (Ontario Chamber of Commerce, 2019[28]) (see Figure 3.18). Nearly half of respondents cited difficulty attracting or retaining staff as a reason for lacking confidence in the economic outlook of their organisations. Ontario Chamber of Commerce members also stressed that recruitment efforts are stifled by a supply/demand mismatch, driven in part by a deficit in areas such as skilled trades, emotional intelligence, design, communication, and STEM. While skills deficits are difficult to tackle over the short-term, a rebalancing of skills supply and demand might prove helpful over the longer term. A further challenge is however posed by the rapid pace of technological change in the workplace.

Ontario has been struggling with skills shortages for more than a decade. A study conducted by the Ontario Chamber of Commerce in 2017 showed that of the 62% of Ontario Chamber of Commerce members who attempted to recruit staff in the last six months of 2016, 82% of them experienced at least one challenge in doing so. The top challenge cited (by 60% of members) was finding someone with the proper qualifications. Employers also have a role to play in ensuring that workers develop the skills needed for job, providing training opportunities. The skills mismatch across Ontario is partly driven by credential inflation, defined as the process of inflation of the minimum credentials required for a given job and the simultaneous devaluation of the value of diplomas and degrees. The decisions of students to pursue qualifications in fields with limited employment opportunities results in an increase in the number of highly educated people working in positions where they are overqualified. This phenomenon ultimately leads to lesser-qualified people out of the labour market. Members of the Ontario Chamber of Commerce also emphasise that the possession of some skills and competencies, such as communication, emotional intelligence, creativity, design, interpersonal skills, entrepreneurship, technological skills and organisation awareness, are needed to succeed in the job (Ontario Chamber of Commerce, 2017[29]).

Figure 3.18. Recruiting and retaining talent is considered the main success factor to organisational competitiveness in Ontario

Source: Ontario Chamber of Commerce (2019[30]), Ontario Economic Report 2019, Ontario Chamber of Commerce, https://occ.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019-Ontario-Economic-Report.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2019).

3.3.5. Qualification mismatches are present in Ontario

While the skills provided by the education and training system need to correspond to those required by firms, it is also important to ensure that the labour market matches workers to jobs in which they can put their skills to the best use. Mismatches between workers skills and the demands of their jobs can have negative effects on different levels. At the individual level, they can affect job satisfaction and wages, at the firm level, they can increase job turnover and potentially reduce productivity, and at the macroeconomic level, they can increase unemployment and reduce growth through the waste of human capital and the implied reduction in productivity (OECD, 2018[31]). Qualification mismatches arise when workers have an educational attainment that is higher (over-qualification) or lower (under-qualification) than that required by their job. OECD research shows that while the share of 15-64 year-old workers who report being over-qualified is slightly lower in Canada than the OECD average (16.2% and 16.8% respectively), the opposite is true when looking at under-qualification (21.7% and 18.9%).

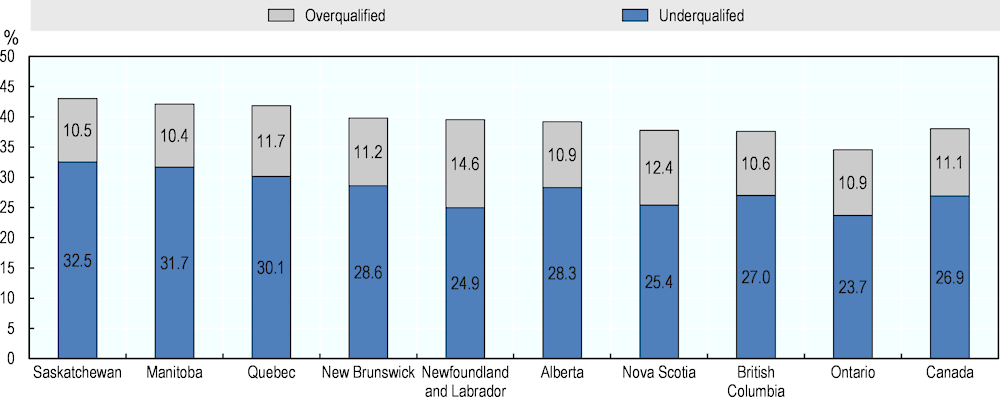

Qualification mismatches are spread in Ontario, although to a lesser extent than in other Canadian provinces (see Figure 3.19). In Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec more than 30% of workers aged 25-64 are underqualified for the job, while less than 25% in Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador. Over-qualification is higher in Newfoundland and Labrador (14.6%) and Nova Scotia (12.4%) compared to other provinces in Canada. Another type of skills mismatch is field of study mismatch, which occurs when workers who were educated in a particular field work in a different one. The 2016 General Social Survey shows that about 36% of Canadian adults are working in a different filed compared to the one in which they studied. Field of study mismatch is generated by both labour supply and demand factors, such as the saturation of a particular field in the labour market and the level of transferrable skills offered by specific fields of study. Linkages between education and the world of work can help provide students with skills needed in the labour market. For example, work-based learning offers useful solutions to the challenge of qualification mismatch as provision adjusts more or less automatically to the needs of the labour market (OECD, 2018[31]).

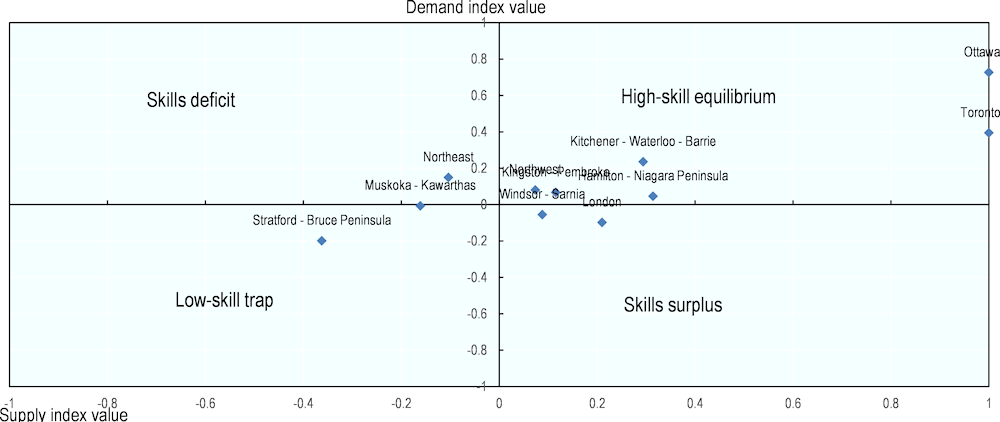

Looking at the occupational structure and educational attainment across regions in Ontario shows that most of them are in a high-skill equilibrium, although differences exist (see Figure 3.20). Ottawa and Toronto are in a high-skill equilibrium, as they are characterised by high educational attainment, high employment shares in high-skill occupations and high earnings. Also Hamilton-Niagara Peninsula, Kitchener-Waterloo-Barrie, Kingston-Pembroke and Northwest are in a high-skill equilibrium. On the other hand, London appears to be facing a skills surplus situation, suggesting that the supply of high-skill individuals is not met by high-skill jobs. The region experienced the least change within Ontario and the relative share of high-skill jobs has even declined slightly during 2011-18. Northeast is the only region in Ontario experiencing a skills deficit, suggesting that although the demand for high-skill jobs is present, this is not matched by an adequate supply of labour force. Finally, Stratford-Bruce Peninsula is in a low-skill trap: both the demand and supply of high-skill jobs and individuals are lacking.

Figure 3.19. Qualification mismatches are present in Ontario, although to a lesser extent than in other provinces

Source: OECD calculations based on Statistics Canada 2016 Census.

Figure 3.20. Most Ontario regions are in a high-skill equilibrium, but differences exist

Box 3.3. A skills demand-supply classification

The OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Programme has developed a typology designed to help understand the main different possible relationships between skills supply and demand at local (or regional) level. Local areas can fall into one of four categories:

High-skill equilibrium, where both the supply of and demand for skills is relatively high;

Skills surplus, where the supply of skills is relatively high but the demand is relatively low;

Skills deficit, where the demand is relatively high but the supply is relatively low; and

Low-skill trap, where both the supply of and demand for skills is relatively low.

When both the supply of and demand for skills is low, a low skills trap can develop within a local economy, which can create a vicious cycle or low investments in skills and poor quality jobs. In such a situation, workers will not have the incentives to upgrade their skills, knowing they will not be able to find jobs in the local economy that use them, and employers may be reluctant to move to more skill-intensive production and services, knowing that they are unlikely to find the workers with the skills needed to fill these positions.

The demand for skills is approximated using a composite index: percentage of the population employed in medium-high skilled occupations and earnings (weighted at .25 and .75 respectively). For building indices it is necessary to bring the variables in a common unit (scale) of measurement using a standardisation method. It was decided to use the inter-decile range method which compares the value of a region with the national median and is not influenced to a great extent by outliers. Using this formula, the supply and demand indices vary between -1 and 1. See the formula below:

(Xi -Xmed) / (X9th - X1st )

Where: Xi = value for TL3i

Xmed= median

X9th = 9th decile

X1st =1st decile

Source: Froy, F., S. Giguère and M. Meghnagi (2012[32]), Skills for Competitiveness: A Synthesis Report, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/skills%20for%20competitiveness%20synthesis%20final.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2019).

3.4. Challenges related to COVID-19 and the future of work require action on both the skills supply and demand

3.4.1. Access to training opportunities is uneven in Canada

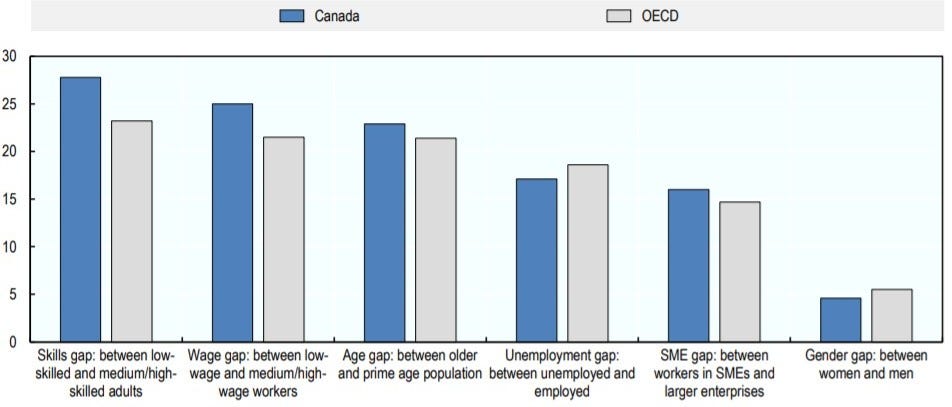

Despite boasting a higher training coverage than other countries across the OECD, access to training is uneven among segments of the population. Two-thirds of adults in Canada received some type of training in 2016, according to the 2016 General Social Survey. Participation rates in Canada are low among low-skill workers, low-waged workers, older workers, the unemployed, those working in SMEs and temporary workers (OECD, 2020[5]) (see Figure 3.21).

Canada displays one of the largest gaps in participation rates between high/middle-skill workers and low-skill workers. Adults with low skills often have limited opportunities to develop their skills further through education and training. Many risk being caught in a ‘low-skills trap’, in low-level positions with limited opportunities for development and on-the-job learning, and experiencing frequent and prolonged spells of unemployment (OECD, 2019[33]). Low-skill workers participate less than higher-skill workers in training, and this gap is larger in Canada than across the OECD (28 relative to 23 percentage points). The growing demand for high-level cognitive and complex social interaction skills suggest that low-skill workers in jobs that are intensive in repetitive or manual tasks are likely to suffer the most from changes related to the future of work (OECD, 2019[4]). Across the OECD, one of the main reasons for the participation gap of low-skill adults in training is that they find it more difficult to recognise their learning needs and hence are less likely to seek out training opportunities (OECD, 2019[33]).

Participation in training is also lower among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and older workers in Canada. For SMEs, lack of time, limited information on training options, and lack of financial resources are often the typical barrier preventing training participation, in Canada as across many OECD countries. In addition, the share of workers who wanted to participate in training but did not because it was too expensive is higher within small than large firms. Training costs may be unaffordable for SME workers who on average earn lower wages and have fewer savings. Also, SME workers more often rely on their own private purse to pay for training, because they are less often beneficiary of employer-provided training, compared to large firms’ workers. The participation gap between the prime age population (25-54) and older adults (55+) is larger in Canada relative to the OECD average (23 and 21 percentage points respectively). Older workers are likely to experience skills obsolescence unless they access training opportunities. Given the shorter period of time that older workers have to recoup the investment in training before retirement, they tend to receive less training than younger workers. Lower participation rates among older adults are often due to high inactivity among older people, low employer investment in the skills of older workers, and fewer incentives for older workers to improve their skills (OECD, 2014[34]).

Figure 3.21. Access to training is uneven across Canada

Note: Participation in formal and non-formal job-related education and training.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en.

3.4.2. COVID-19 makes skills development more important than ever, as it can prepare workers for the upturn

Investments today in lifelong learning and vocational training can ensure workers are ready for the upturn, while also supporting regions to make transitions to new economic opportunities. During the previous crisis in 2008, investments were aimed at helping individuals acquire skills in new and emerging sectors. However, such efforts were sometimes undermined by low firm demand and sub-optimal use of those skills in the workplace. Policy could focus on providing flexible forms of skills development to respond to the accelerated reallocation of labour in local economies, including greater access to e-learning opportunities that focus on the needs of the worker (especially those who are disadvantaged) while working with firms to promote workforce innovation and better human resources management practices. This tailoring and proximity to firms and workers will be an essential asset for the recovery (OECD, 2020[35]).

Closing gaps in access to training will be particularly important, given the uneven impacts of COVID-19 across the skills spectrum. Low-skill, low-wage, and young people may be the most vulnerable to job losses as they are employed in the sectors most at risk today, they are less likely to hold jobs that allow them to telecommute, and are more likely to be on temporary contracts. These same groups are also more likely to hold jobs at higher risk of automation, a process that firms may accelerate in light of the pandemic (OECD, 2020[35]). Going forward, it will be crucial to ensure that these categories of workers can access skills development opportunities to prepare for the upturn and transition into new jobs.

3.4.3. Digital skills are in need across Canada

COVID-19 is pointing out the importance of digital skills in the labour market. The crisis has accelerated the adoption of digitalisation in the workplace, to help reduce avoidable physical interactions. This has meant finding ways to reinvent work and, in some cases, a partial disruption of jobs and changes in the way workers perform them (McKinsey & Company, 2020[25]).

Digital skills were in high-demand across sectors in Canada already before the COVID-19 outbreak. The Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship (BII+E) has developed a taxonomy of digital skills and explored patterns in digital skill demand across Canada and Ontario. It has drawn on six years of online job postings data from Burning Glass Technologies (Burning Glass), including about three million job postings recorded for Ontario over this period, representing over 40% of online job postings in Canada. Digital skill demand in Canada is not monolithic. Digital skills vary widely, and can be understood as belonging to four clusters (see Box 3.4).

Digital skills are more in demand in Ontario than across Canada. A weighted average of the share of digital skills across almost 1 000 occupational groups reveals that while an online job posting in Canada typically consists of 13% digital skills, in Ontario, this share is over 16% (or 25% higher than the Canadian share). This difference is seen across all four digital skill clusters. The ten digital skills that show up most frequently in Ontario are the same 10 digital skills that show up most frequently in Canada overall. These include baseline digital skills, such as proficiency using the Microsoft Office suite, in particular Excel, as well as more specialized digital skills such as SQL, a querying language, and Java, a programming language (see Table 3.1).

Box 3.4. Digital skill clusters in Canada

In ascending order of digital intensity, these are: Workforce Digital Skills, Data Skills, System Infrastructure Skills, and Software/Product Development Skills. BII+E identified these clusters by first delineating between digital and non-digital skills based on the occupational contexts in which skills are demanded, including whether they consistently and uniquely show up in digital occupations as defined in BII+E’s previous work, and on Burning Glass’s existing categorisation of software skills. BII+E then used graph theory and network analytics techniques to identify clusters of digital and non-digital skills.1

Workforce Digital Skills (997 skills): This skill cluster is the least digitally-intensive, comprising skills ranging from those associated with general office tasks to those associated with specific professions, such as use of architectural and engineering-based software to augment job tasks and business processes. Prominent skills in this cluster include Microsoft Excel, Word, PowerPoint, and Office (741 191, 296 992, 266 792, and 621 690 mentions respectively). This cluster also includes skills associated with general-use design software, such as Adobe Photoshop (53 855 mentions), as well as basic data analysis skills (mentioned 60 256 times) and use of tools such as SAS (21 130 mentions).

Data Skills (507 skills): This skill cluster is focussed primarily on data gathering and analysis, especially in large-scale enterprise analytics. The skills in this cluster are important across the economy and have a wide variance in their digital intensity. Prominent skills include “Data Modeling” (20 252 mentions), “Big Data” (13 173 mentions), “Business Intelligence” (35 361 mentions), and familiarity with data analytics tools, such as Apache Hadoop (10 509 mentions), Tableau (9 121 mentions), and R (4 132 mentions). This cluster can be further divided into basic data skills, which intersect with the Workforce Digital Skills cluster, and two groups of advanced data skills: Data Infrastructure, which intersects with the System Infrastructure cluster; and AI/Machine Learning skills, which intersect with the Software/Product Development cluster.

System Infrastructure Skills (985 skills): This cluster consists of skills related to digital infrastructure management, ranging from setting up and managing cloud computing services to general IT support. Prominent skills include proficiency with specific platforms such as VMWare (25 319 mentions) or Windows Server (21 094 mentions), and general support skills such as ‘system administration’ (33 459) and ‘hardware and software installation’ (23 940 mentions).

Software/Product Development Skills (1 109 skills): This skill cluster pertains to the generation of new digital products, both web- and software-based. Prominent skills include proficiency in programming languages, such as Java (112 680) and Python (43 137 mentions), and general skills such as ‘software development’ (133 681 mentions), ‘software engineering’ (47 775 mentions), and ‘web development’ (41 184 mentions). Some technical design skills, pertaining specifically to web development, are also a part of this cluster. On average, skills in this cluster are the most digitally-intensive.

1. In BII+E’s I, Human report, “skills” is used as a catch-all for skills, abilities, knowledge, and other elements required for workers to be successful in a job

Source: Vu, V., R. Willoughby and C. Lamb (2019[36]), I, Human: Digital and soft skills in a new economy, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/I-Human-ONLINE-FA.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

Table 3.1. Top digital skills for Ontario

|

Skill |

Number of Job Postings |

|---|---|

|

Microsoft Excel |

382 851 |

|

Microsoft Office |

306 588 |

|

Microsoft PowerPoint |

149 155 |

|

Microsoft Word |

145 048 |

|

SQL |

100 167 |

|

Software Development |

76 120 |

|

Spreadsheets |

73 447 |

|

Java |

68 847 |

|

Technical Support |

64 084 |

|

SAP |

62 525 |

Source: Vu, V., R. Willoughby and C. Lamb (2019[36]), I, Human: Digital and soft skills in a new economy, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/I-Human-ONLINE-FA.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

Digital skill demand varies across local economies in Ontario. When comparing the three focus jurisdictions — London, Kitchener, and Hamilton — to other provincial jurisdictions, including Ottawa, Toronto, and Waterloo, it is clear that the digital skills employers are seeking differ depending on the jurisdiction. In all local economies, demand for employees with the ability to use the Microsoft Office suite is high, but beyond this, important differences arise. For example, demand for skills from the Software/Product Development cluster is significantly higher in Waterloo, while in Hamilton, no skills from this cluster rank among the top 10 in-demand digital skills for this region. All of the top 10 digital skills asked for in Hamilton are general workforce digital skills. In Kitchener, skills from both the Software/Product Development and Data clusters are in high demand. Interestingly, however, SAP, which appears in both the national and provincial top 10 list, is the 29th most requested skill, while other software and product development skills, such as “Software Engineering,” “Linux,” and “C++,” appear more often. For London, skills from the Software/Product Development cluster appear less often, with JavaScript appearing as the 13th most commonly requested skill, and Java as the 17th most requested. Workforce digital skills such as “Spreadsheets,” “Word processing,” and “Technical Support” appear more frequently.

Table 3.2. Top digital skills in Kitchener

|

Skill |

Number of Job Postings |

|

Microsoft Excel |

5 388 |

|

Microsoft Office |

4 988 |

|

Microsoft Word |

2 306 |

|

Microsoft PowerPoint |

1 633 |

|

SQL |

1 557 |

|

Software Development |

1 310 |

|

Spreadsheets |

1 071 |

|

Java |

1 027 |

|

JavaScript |

986 |

|

Technical Support |

961 |

Source: Vu, V., R. Willoughby and C. Lamb (2019[36]), I, Human: Digital and soft skills in a new economy, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/I-Human-ONLINE-FA.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

Table 3.3. Top digital skills in London

|

Skill |

Number of Job Postings |

|

Microsoft Excel |

13 830 |

|

Microsoft Office |

13 251 |

|

Microsoft Word |

5 444 |

|

Microsoft PowerPoint |

4 393 |

|

Spreadsheets |

2 564 |

|

Technical Support |

2 409 |

|

SQL |

2 118 |

|

Word Processing |

1 889 |

|

Software Development |

1 879 |

|

SAP |

1 639 |

Source: Vu, V., R. Willoughby and C. Lamb (2019[36]), I, Human: Digital and soft skills in a new economy, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/I-Human-ONLINE-FA.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

Table 3.4. Top digital skills in Hamilton

|

Skill |

Number of Job Postings |

|

Microsoft Excel |

7 539 |

|

Microsoft Office |

6 143 |

|

Microsoft Word |

3 305 |

|

Microsoft PowerPoint |

2 204 |

|

Spreadsheets |

1 601 |

|

Word Processing |

1 202 |

|

Microsoft Outlook |

1 026 |

|

Technical Support |

938 |

|

Telecommunications |

886 |

|

SAP |

869 |

Source: Vu, V., R. Willoughby and C. Lamb (2019[36]), I, Human: Digital and soft skills in a new economy, https://brookfieldinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/I-Human-ONLINE-FA.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

3.4.1. Digital skills are important, but not in isolation

While digital skills are in need across Ontario, this is not in isolation. BII+E has identified some trends shaping Canadian labour markets, whereby employers are seeking digital and non-digital skills in combination, i.e. “hybrid jobs”. Canadians across the economy require a skillset that includes general workforce digital skills and a suite of soft skills. Despite a growing narrative around the importance of learning to code, for most Canadians, foundational digital skills alongside a suite of non-digital skills — in particular, interpersonal skills — are critical foundations to be competitive in the labour market. General workforce digital skills, while less digitally-intensive, show up in roughly one third of all job postings in Canada. This includes the baseline digital skills that most Canadian workers need, the most predominant of which are those found in the Microsoft Office Suite. It also includes occupation-specific software, such as business intelligence software and SAS. The most common skills appearing alongside workforce digital skills are communication and organisational skills. Other soft skills likely to appear alongside workforce digital skills include interpersonal skills, such as ‘teamwork’, ‘collaboration’, and ‘customer service’; project management skills, such as ‘budgeting’ and ‘planning’; and more general skills and aptitudes, such as ‘problem-solving’ and ‘detail-orientedness’.

For highly technical workers, digital skills are necessary, but they should be complemented by non-digital skills. Roles requiring a high proportion of skills from the Software/Product Development and Systems Infrastructure skills clusters are not only the most digitally-intensive, but also the most hybrid. This means that in addition to digital skills, employers look for non-digital skills from different domains at a higher intensity compared to other roles. For these highly-digital roles, employers are looking for particularly dynamic candidates, with technical domain knowledge augmented by many non-digital skills; in particular, those that pertain to communications, teamwork, problem solving, and project management, reflecting the creative and collaborative nature of these roles. For current and prospective workers in these fields, strong digital skills are necessary, but insufficient. It is perhaps just as critical to enhance one’s interpersonal, creative, and problem-solving skills and abilities.

For many professionals in creative sectors, design-oriented digital skills are essential. In many core creative roles, from advertising professionals to video game designers, employers are looking for candidates with a strong overlap in non-digital communications, marketing, and/or design skills, as well as design-oriented digital tools. The digital skills that are in-demand for these creative professionals pertain to graphic design, web development, and marketing/communications. For these workers, the tools from the Adobe Creative Suite are requested most often. Many of these jobs also require digital skills that relate to marketing and communications — the ability to use social media platforms were among the most commonly requested. Digital marketing management tools and general web development skills are also in high demand. From an employer perspective, the core creative practices, which include non-digital communications, marketing, and design skills, remain the most important elements of the job; but, in many cases, these need to be augmented by specific digital skills and abilities.

Data skills are highly in-demand and act as connectors between less and more digitally-intensive occupations. Data is becoming an indispensable component of our economy. For workers, data skills are not only some of the most in-demand digital skills, but can also serve as a link between less and more digitally-intensive roles. One area of upgrading that offers promise is advancement from Microsoft Excel to SQL. Microsoft Excel is the single most in-demand digital skill in Canada, and as a spreadsheet programme is applicable across the economy. SQL, a database querying software, is much more digitally-intensive, but is also the fifth most requested digital skill in Canada. While these skills sit within two distinct clusters, with different levels of digital intensity, they also form a strong connection with one another. There are many instances in which an employer asks for both Excel and SQL in the same job posting. An individual who is proficient at Excel and seeking to become more competitive in digitally-intensive roles may consider learning SQL. However, these kinds of job transitions will also likely require skill and credential upgrading in other areas (Vu, Willoughby and Lamb, 2019[36]).

Previous OECD work has also stressed the importance of expanding entrepreneurial education in Canada, to develop skills and confidence in potential entrepreneurs and increase their likelihood to innovate and succeed (OECD, 2017[37]). There are many examples of the use of entrepreneurship education tools in Canadian schools. However, some provinces (notably Quebec and Ontario) are forging ahead of others and some activities are limited on the ground, such as contacts between inspiring role models and students; school trips to local business incubators and enterprises; summer camps for successful participants of entrepreneurship competitions; and online competitions and virtual firm games. At tertiary level, almost all institutions offer a few entrepreneurship courses and extra-curricular activities such as workshops, business competitions and mentoring. Some jurisdictional apprenticeship authorities in Canada deliver an Achievement in Business Competencies (Blue Seal) Program, a credential to help certified skilled trades workers succeed in business. However, the proportion of students reached is limited and many of the activities depend on the efforts of a few individuals rather than institutionalised processes.

3.4.1. Improving the use of skills in the workplace is an opportunity for Ontario

Having a workforce with the right skills is not sufficient to achieve growth and foster productivity. For economies to grow and individuals to succeed in the labour market, skills need to be put to productive use at work (OECD, 2016[38]). Traditionally, workforce development initiatives have focused on the supply side of labour markets: job search, matching, skills development, and addressing employment barriers faced by vulnerable groups. However, there is increasing recognition of the value of demand-side efforts, including engaging employers in making optimal use of their employees’ skills (OECD/ILO, 2017[39]).

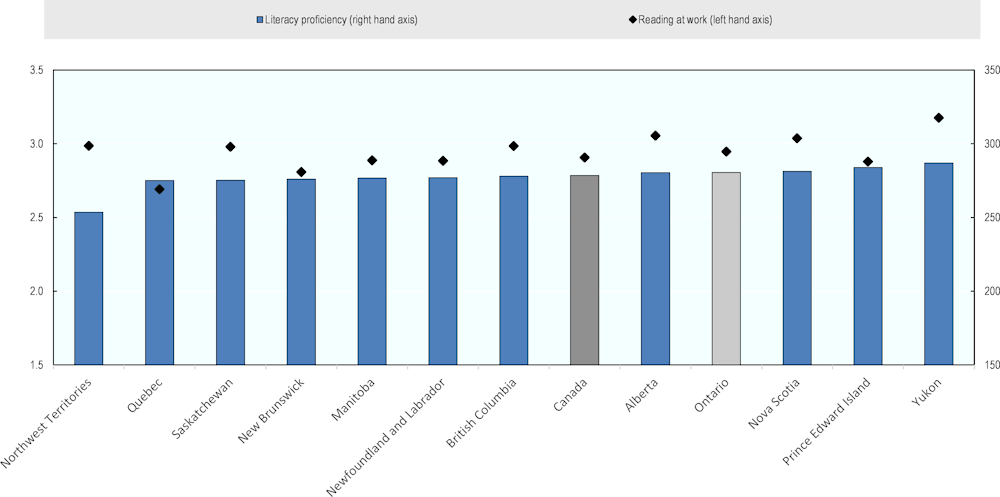

While Ontario achieves high levels of literacy proficiency compared to most provinces, it scores in the average when it comes to reading skills use at work. Better using skills in the workplace represents an opportunity for Ontario, as the use of reading skills at work strongly correlates with output per hour work, even accounting for average proficiency scores in literacy and numeracy, suggesting that the frequency with which skills are used at work is important in itself (OECD, 2016[38]). In addition, workers who use their skills more frequently also tend to have higher wages, even after accounting for differences in educational attainment, skills proficiency and occupation. Effective skills use is also traditionally linked to higher job satisfaction.

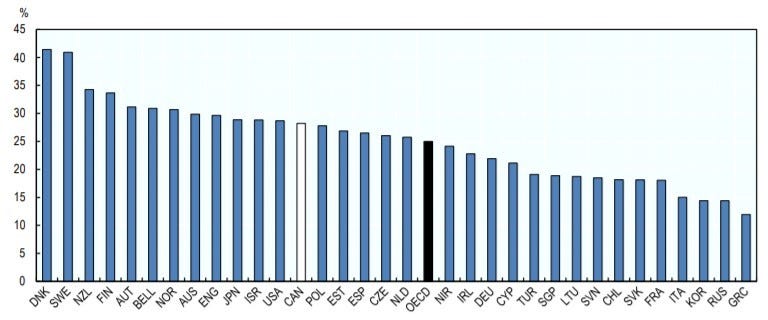

Promoting the emergence of high-performance work practices could be a means to putting skills into good use in Ontario. The term “high performance work practices” (HPWP) refers to a set of human resources practices that are shown to be associated with greater skills use and informal learning. HPWPs include aspects of work organisation and job design (such as teamwork, autonomy, task discretion, mentoring, job rotation, applying new learning), as well as management practices (such as employee participation, incentive pay, training practices and flexibility in working hours). In Canada, 28% of firms employ some type of high-performance work practice on a weekly basis, which is just ahead of the OECD average (25%), but behind top performers Denmark (41%), Sweden (41%), and New Zealand (34%) (see Figure 3.23). The use of HPWP is more common among large firms than in SMEs and high-skill workers are more likely to be engaged in HPWP than less-skill workers (OECD, 2019[40]). Some sectors are more likely to employ HPWPs (see Figure 3.24). Over 35% of firms in information and communications, utilities and professional, scientific and technical services employ HPWP, while less than 20% of firms in primary industry (agriculture, forestry, fisheries) and transportation and storage do. Further, there is variation in the likelihood of employing HPWPs across firms in different provinces and territories (see Figure 3.25). Firms in the central and western provinces of Canada are more likely to participate in HPWPs on a weekly basis than those in the eastern provinces, which likely reflects differences in industry composition across provinces and territories. Looking specifically at literacy and reading skills across Canada, Ontario emerges as one of the provinces with the highest performance in literacy proficiency, after Yukon, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. However, looking at the reading at work indicator, Yukon, Alberta, Nova Scotia, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories show higher scores than Ontario.

Figure 3.22. Literacy proficiency and reading at work across Canada

Figure 3.23. More employers in Canada employ some type of HPWP than on average across the OECD, but less than best performing countries

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en.

Figure 3.24. The adoption of HPWP varies across sectors in Canada

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en.

Figure 3.25. The adoption of HPWP varies across provinces and territories in Canada

Source: OECD (2020[5]), Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a92cf94d-en.

Conclusion

Job polarisation has led to a hollowing-out of the employment share of middle-skill jobs in Canada as in most OECD countries. The share of middle-skill jobs has declined in all Canadian provinces, but this masks substantial differences within provinces. For example, in 5 out of 11 Ontario regions the relative importance of middle-skill jobs over total employment has increased over recent years. Dynamics in job polarisation partly reflect trends in the supply for skills across Canada. In Ontario, large urban centres attain higher levels of education than other regions. Polarisation takes place at a moment when labour shortages and skills mismatches are having a profound impact on labour markets across Canada. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is likely going to exacerbate labour and skills shortages going forward, and is making skills development and skills use crucially important. More employers than ever require workers to have digital skills. At the same time, workforce training and skills development, as well as a better use of skills in the workplace, represent an opportunity to make better use of the available workforce. The next chapter outlines examples of policies and programmes being implemented in Canada with a special focus on the Province of Ontario to prepare people, places and firms for the future of work.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2010). Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings. NBER Working Papers Series. Retrieved 02 20, 2020, from http://www.nber.org/papers/w16082

Adalet McGowan, M., & Andrews, D. (2017). Skills mismatch, productivity and policies: Evidence from the second wave of PIAAC. In OECD Economics Department Working Papers. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/65dab7c6-en

Autor, D., Katz, L., & Kearney, M. (2006). The Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w11986

Autor, D., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. (2003). The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: an Empirical Exploration*. Retrieved 02 20, 2020, from https://economics.mit.edu/files/11574

Bank of Canada. (2019). Business Outlook Survey—Autumn 2019. Retrieved 01 23, 2020, from https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2019/10/business-outlook-survey-autumn-2019/

Breemersch, K., Damijan, J., & Konings, J. (2017). Labour Market Polarization in Advanced Countries: Impact of Global Value Chains, Technology, Import Competition from China and Labour Market Institutions. In OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/06804863-en

Business Development Bank of Canada. (2018). Labour Shortage in Canada: Here to stay. Retrieved 02 21, 2020, from https://www.bdc.ca/en/documents/analysis_research/labour-shortage.pdf

Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB). (2019). Labour shortages are holding back the construction sector: Here’s what governments and businesses can do. Retrieved 03 12, 2020, from https://www.cfib-fcei.ca/en/media/labour-shortages-are-holding-back-construction-sector-heres-what-governments-and-businesses

Das, M., & Hilgenstock, B. (2018). The Exposure to Routinization: Labor Market Implications for Developed and Developing Economies. Retrieved 02 20, 2020, from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/06/13/The-Exposure-to-Routinization-Labor-Market-Implications-for-Developed-and-Developing-45989

Froy, F., Giguère, S., & Meghnagi, M. (2012). Skills for Competitiveness: A Synthesis Report. OECD. Retrieved 07 11, 2019, from http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/skills%20for%20competitiveness%20synthesis%20final.pdf

Goos, M., & Manning, A. (2007). Lousy and Lovely Jobs: The Rising Polarization of Work in Britain. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1), 118-133. doi:10.1162/rest.89.1.118

Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2009). Job Polarization in Europe. American Economic Review, 99(2), 58-63. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.58

Government of Ontario. (2020). Ontario Preparing People in London for Jobs. Retrieved 02 26, 2020, from https://news.ontario.ca/mol/en/2020/01/ontario-preparing-people-in-london-for-jobs.html

Komarnicki, E. (2012). Labout and Skills Shortages in Canada: Addressing Current and Future Challenges. Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities. Retrieved 01 23, 2020, from http://publications.gc.ca

ManpowerGroup. (2018). 2018 Talent Shortage - Solving the Talent Shortage: Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge. Retrieved 08 01, 2019, from https://manpowergroup.ca/campaigns/manpowergroup/talent-shortage/pdf/canada-english-talent-shortage-report.pdf

Marcuse, P. (1989). ‘Dual city’: a muddy metaphor for a quartered city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 13(4), 697-708. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.1989.tb00142.x

Matti, M. (2019). Canada's skilled labour shortage: What does it mean and what can employers do about it? Retrieved 03 12, 2020, from https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/canada-s-skilled-labour-shortage-what-does-it-mean-for-workers-and-employers-1.4623996