COVID-19 is having profound impacts on communities in Canada as around the world. Challenges associated with COVID-19 and the future of work will diverge by local economy, depending on the profile of the local labour market. This chapter provides a framework for understanding how current technological developments differ compared to previous waves. It also outlines examples of policies and programmes being implemented in Canada, with a special focus on the Province of Ontario, to prepare workers for the upturn, while addressing the specific challenges facing people, places and firms in keeping pace with the future of work.

Preparing for the Future of Work in Canada

4. Future-proofing people, places and firms in Canada

Abstract

In Brief

COVID-19 is having profound impacts on communities across Canada. The Government of Canada has put in place a series of measures aiming to provide income support to workers who have lost their job and segments of the population hit particularly hard by the pandemic.

The pandemic hits at a time when technology is re-shaping the way people live and work. In the new wave of technological developments, machines are learning over time and accumulating knowledge. Automation is likely to replace tasks within jobs rather than entire jobs, enabling greater competition in the global skills market and creating demand for new skills.

COVID-19 and the future of work will affect people, places and firms differently. Both federal, provincial and territorial governments in Canada are taking action. In 2019, the Government of Canada launched Future Skills to help ensure Canada’s skills policies and programmes are “future fit”. Future Skills aims to ensure jobseekers, workers and employers continue to have access to skills development programmes that meet their evolving needs and better position them for success into the future. This public policy will be critical in nudging people, places, and firms to think more critically of future employment and skills development opportunities.

The Province of Ontario has been at the forefront of designing innovative policy responses to help people, places, and firms make transitions. Programmes such as Second Career and the Canada-Ontario Job Grant are providing skills training opportunities linked to growing and emerging sectors of the Canadian economy. These programmes will be even more crucial to help workers develop skills which could help them find jobs once the pandemic is over.

SMEs often struggle more than larger companies in accessing the skills they need and developing their workforce talent. As SMEs account for substantial shares of employment across Canada and within the Province of Ontario, targeted strategies to ensure SMEs invest in preparing their workforce for future changes in the labour market are needed.

Introduction

COVID-19 is disrupting communities across Canada as in the whole world. This happens at a time when technology was already changing the way people live and work. This report has demonstrated that the impact of new technologies will vary by place depending on the occupational profile of the local labour market. As some people and firms will also be more affected by technological developments than others, the uneven impact of automation and digitalisation requires targeted policy responses. Sections 4.1 and 4.2 of this chapter provide a conceptual framework for analysing the impact of new technologies on jobs and skills in Canada. Sections 4.3 and 4.4 provide information on new actions that are being taken to prepare for the future of work at the federal and provincial level in Canada. Section 4.5 focuses on the needs of small and medium sized enterprises, which require more customised solutions to participate in workforce development programmes.

4.1. A changing world of work requires re-thinking traditional policy approaches

4.1.1. COVID-19 is posing unprecedented challenges to communities in Canada as around the world

COVID-19 is having a widespread impact across communities in Canada. While considered necessary for reducing the risk of spreading COVID-19, confinement measures are putting unprecedented pressure on local labour markets and economies. COVID-19 is causing dramatic losses in employment. Total employment declined by 10% in all Canadian provinces between February and April 2020, led by Quebec (-18.7%, or -821 000 jobs). Employment also dropped sharply from February to April in each of Canada's three largest census metropolitan area (CMAs). Montréal recorded the largest decline (-18.0%; -404 000), followed by Vancouver (-17.4%; -256 000) and Toronto (-15.2%; -539 000). COVID-19 is impacting vulnerable workers the most. In April, employment losses continued to be more rapid in jobs offering less security, including temporary and non-unionized jobs. Between February and April, the number of people aged 15 and older living in economic families (which includes people living alone) where no one is employed has increased by 23.5% (+1 655 000) (Statistics Canada, 2020). As of May, the gradual easing of COVID-19 restrictions has been accompanied by initial rebounds in employment. Employment rose by 290 000 (+1.8%), while the number of people who worked less than half their usual hours dropped by 292 000 (-8.6%). Combined, these changes in the labour market represented a recovery of 10.6% of the COVID-19-related employment losses and absences recorded in the previous two months (Statistics Canada, 2020).

4.1.2. COVID-19 is hitting at a time when new technological developments are changing the way people live and work

New technologies including automation have disrupted the existing order ever since the invention of the wheel. In modern history, the big disruption came from the industrial revolution in the mid-19th century but waves of disruption have followed every few decades ever since. Each wave of new technology altered the existing pattern of jobs and skills. Despite fears, technological innovations have always given rise to new jobs that provided employment, while the productivity growth from automation has been an important driver of rising living standards (OECD, 2018). However, automation has also posed challenges: the labour saving effect linked to automation can be sudden, whereas it might take considerable time until new jobs are created that replace the lost jobs. At the same time, the skill profiles of jobs lost to automation and the skill profiles of the jobs replacing them are not necessarily the same.

In the current wave of technological disruption, the concept of “smart” machines is rapidly changing what we produce and how we produce using technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), self-learning machines (SLMs), algorithm-based technologies, and digital fabrication. This newer wave of technology is qualitatively different from previous generations of automation. Because these machines can “learn” over time they can acquire and accumulate knowledge to enhance their ability to make accurate decisions. Given the ability of this wave of technology to disrupt the existing order, policy needs to investigate ways to mitigate the adverse effects while taking advantage of the opportunities offered by these new technologies. Hosanagar (2019) argues that only a better, deeper, more nuanced understanding of algorithmic thinking can prepare us to meet the full challenge of these adaptive technologies, pointing out that algorithms function a lot like their programmers who are, after all, human.

4.1.3. Several other forces have affected people’s lives over the past decades

These new technologies are emerging at a time when several other forces are shifting the context for people around the world. New technologies, together with globalisation and population ageing are having profound impacts on the type and quality of jobs available and the skillsets they require. The number of manufacturing jobs in advanced economies has decreased and an increasing number of the remaining jobs requires workers to have new skills. Meanwhile, new jobs have emerged that did not exist in the past, requiring new skills, such as data scientists, social media managers and web developers. Both technological change and globalisation have created new jobs, like big data managers, robot engineers, social media managers and drone operators – all occupations that did not exist a generation ago. In addition, entirely new jobs may be created in the future as a result of innovations, either to complement machine capabilities within existing occupational categories (e.g. new types of teachers who blend in-class and computer-based learning) or in entirely new fields (e.g. social media managers, internet of things architects, AI experts, user-experience (UX) designers, etc.) (OECD, 2019). Environmental degradation and environmental sustainability are also identified as trends that will profoundly shape the future of work, given the tight link between economic activity and the natural environment (International Labour Organization, 2018).

Much anxiety surrounds the future of work. Doomsday scenarios are unlikely to materialise, but there are some risks (OECD, 2019). In the absence of policy interventions, disruptive changes might lead to greater inequality, environmental unsustainability and the exclusion of certain groups of people, which would eventually threaten the prosperity that comes from economic growth. Shaping a future of work that is more inclusive and rewarding calls for a whole-of-government approach that targets interventions on those who need it most. Such a policy agenda would need to cover education and skills, public employment services and social protection, but also labour market regulation, taxation and even housing, transport, competition law and industrial policy (OECD, 2019).

While COVID-19 is likely to accelerate the speed of automation, it could lead to a slowdown of globalisation and a delocalisation of production and industry jobs. Disruptions in global supply chains and shortages in equipment or pharmaceuticals produced abroad have opened up new questions in the debate about the pros and cons of globalisation. Production activities could be re-shored, especially in relation to priority goods in health care. Shorter food production could be promoted. There are opportunities for local economies to diversify economic activity and restore middle-skill jobs, but this trend could also negatively affect local economies specialised in tradable goods (OECD, 2020).

4.2. Technological disruption, jobs and skills

Little is known about the shape and extent of the impacts of new technologies on people’s work, which limits the scope for predictions. Notwithstanding such uncertainty, some trends have emerged already that can guide policy responses for the future. In this context, COVID-19 is likely to accelerate the adoption of technologies in the workplace. To reduce their exposure to any potential future social distancing and confinement measures, more firms could decide to invest in technology to automate the production of goods and services. In addition, the adoption of automation in the workplace tends to accelerate in times of economic crises, as firms replace workers performing routine tasks with a mix of technology and better-skilled workers.

4.2.1. New technologies are more likely to replace tasks within jobs than entire jobs

A process of creative destruction is under way, whereby certain tasks are either taken over by new technologies or offshored, and other, new ones, are created (OECD, 2019). Automation is often portrayed as an intelligent robot that would replace a given job in its entirety, with the idea of a driverless car as the best example of such fear. An entire job, the driver, would be replaced by technology that would allow a car to drive from point A to point B without the help of a human driver. In reality, this scenario in which a current job done by a human being is taken over by a robot is likely to be the exception, not the rule. In the case of the vast majority of jobs, technology is likely to automate a few tasks or several tasks but not all the tasks.

These trends make promoting effective adult education and training a much needed policy intervention to provide workers with re-skilling and up-skilling opportunities (OECD, 2019). He and Guo (2018) simulate the application of automation to the financial sector in China to conclude that while 23% of jobs in this sector would be cut or modified, the remaining 77% of jobs would be enhanced in their efficiency through the use of these technologies. Bughin (2018) supports this assessment of the effect of automation by pointing out that the trend in reduction of labour/output ratio, around 1% per annum, has not changed in recent years and is unlikely to change between now and 2030.

Workers affected by technology need to be helped to move quickly to new jobs through effective and timely employment services, as well as prevention and early intervention measures. Adequate income support tied to incentives and support for active job search is also critical in reducing the individual and social costs of these adjustment processes, and can play a stabilising role in the current context of uncertainties about the future of work. Tackling gaps in income support, which typically serves as the main gateway to labour market reintegration measures, may require extending support for jobseekers with intermittent, low-paid or independent employment (OECD, 2019).

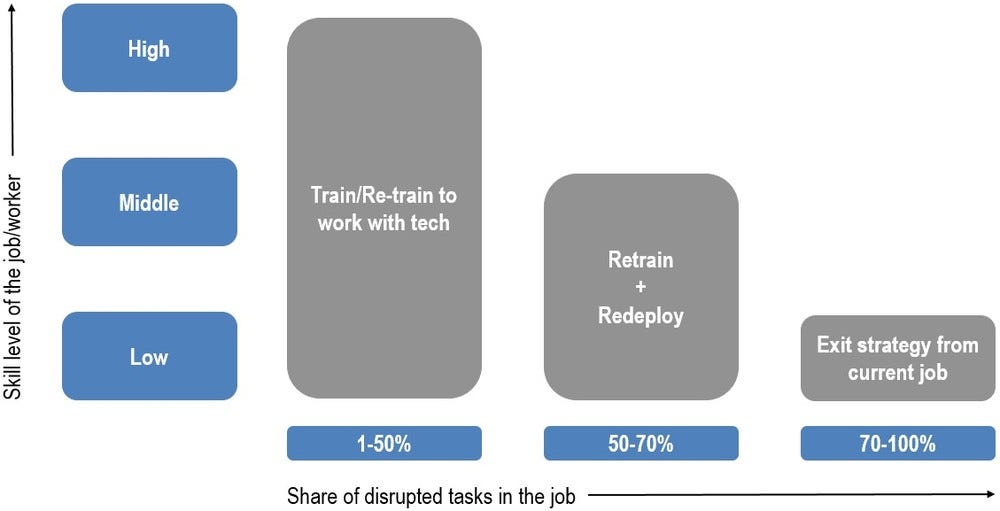

Automation’s impact on jobs can be considered in several steps. First, automation will lead to a redefinition of tasks and jobs. The second step is to consider the skills needed for the tasks and whether these skills could be supplied by imparting training to the job incumbent or if there is a need to hire new employees. This describes a job-centric approach to considering automation’s impact and the related policy response. A complementary approach is to focus on the worker as opposed to the job. A worker-centric analysis would factor in both the extent of automation disruption as well as the current skills, education and ability of the worker to adapt to the demands of the new technology.

4.2.2. Automation will have an impact across the skill spectrum, although some jobs will be more affected than others

Over the last two decades, employment in manufacturing has decreased by 20% across the OECD, while employment in services has grown by 27%. Labour markets have become more polarised, with increasing shares of low-skill and high-skill jobs, while middle-skill jobs have been hollowed out. Skill-biased technological change has been the main driver behind these trends. While manufacturing is considered a sector at high risk, so are many service sectors. Health, education and the public sector may face lower risks of facing disruption due to automation, but they typically employ many people across the OECD. Changes are likely to affect many workers (OECD, 2019).

It is therefore expected that the impact of automation would be felt across the entire spectrum of jobs ranging from low-skill to the highest-skill jobs. Every job and worker would need to adapt to these technologies to some extent. For jobs that have a relatively small share of tasks at risk of automation, some training on how to incorporate those technologies into their current jobs would be needed. While the need for such training, either formal or non-formal, would be felt all across the skill spectrum, the amount of training needed would vary based on workers’ skills. Low-skill workers would particularly benefit from increased access to training, as occupations requiring no specific skills and training have the highest risk of being automated. However, they typically face more challenges than higher-skilled workers in accessing training, also due to the nature of their employment.

For occupations where the share of tasks threatened by automation is in the mid-range, some jobs would need to be combined to form new job descriptions. Workers in these occupations will need to be re-deployed across locations and possibly, employers and industries. The number of jobs and people in this category can be expected to be smaller than the first category. Lastly, the share of tasks affected by automation would be large, in some jobs that would be mostly low-to-middle-skill in nature. These jobs could be gradually eliminated and the people in it would need an exit strategy from their existing job.

Figure 4.1. A model of jobs disruption and policy responses

Note: The figure presents a simplified illustration based on the authors’ elaboration and model.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

4.2.3. COVID-19 and new technologies make adult education and training even more relevant

Maintaining the skills acquired in youth will not be sufficient for workers to adapt to labour market developments linked to COVID-19 and the future of work. Instead, workers will need to acquire and develop skills in demand in the labour market that will allow them to transition to new tasks throughout their working lives. Career transitions, especially when they occur in mid- or late-career, are often far from being smooth. Technological development has also led to increased competition between workers around the world. Online labour platforms enable firms to call on workers elsewhere with a variety of skill levels, possibly at the expense of investing in the skills of their employees (OECD, 2019). Sending radiology scans overseas for a detailed analysis and report, is a good example of this effect of new technology. These trends suggest that more repetitive tasks performed by higher skill professionals and technicians can also be disrupted by newer forms of automation.

In a labour market disrupted by COVID-19, new technologies and global integration, among other measures, it is important to increase investment in people’s capabilities. This approach goes beyond simply investing more in human capital to a broader concept of meaningful and inclusive development that leaves no one behind. Investments in lifelong learning would enable people to acquire skills, re-skill and up-skill, many times over the life course. Action on the adult learning front is a priority, as in view of the scope and speed of changes taking place, marginal adjustments are unlikely to be sufficient, and a substantial overhaul of adult learning policies is needed to make adult learning systems future-ready for all (OECD, 2019). It should also be recognised that some people might not wish to continue learning and policy and programme responses should therefore consider how different kinds of barriers, including resistance and disinterest, may be addressed.

A recent study identifies individual and firm level factors that hinder career transitions (Lamb, Vu, & Huynh, 2019). At the individual level, health, age, gender, financial resources, geography, unemployment spells and “mindset” are factors that can hinder or facilitate transitions. At the firm level, educational credentials, social and cultural capital are relevant factors in determining success in career transitions. The study examined career transitions in two clusters where jobs have declined in recent years: clerks from the financial services sector and motor vehicle technicians. It found that in the case of clerks from banks and insurance companies, over 90% of their knowledge and skills made them eligible to bid for jobs in three areas where jobs have been growing: financial sales, human resources and executive assistants. In the case of motor vehicle technicians, whose numbers have been declining, 84-87% of their knowledge and skills fit with technicians in mechanical engineering and electrical engineering, where jobs have been growing. Therefore, while pathways are feasible this information regarding knowledge and skills overlap need to be studied, developed and disseminated to employers and jobseekers alike. These are the areas where new policies and programmes can help smoothen career transitions that are likely to become increasingly necessary.

4.2.4. Technological disruption requires local partnerships for adult education and training

The costs of skill formation in the wake of automation disruption can vary based on the extent of disruption. At the low end, on-the-job training for people whose jobs are likely to experience minimal change can be delivered relatively inexpensively. However, skill development costs rise rapidly when the required response entails re-training and re-deployment, and it is much higher if people return to school later in life. Much of the accumulated evidence on automation to date suggests that the need for skill development across the entire economy will become increasingly acute. Given that disruption is likely to affect workers in some occupations and sectors more than others, and these not equally distributed within countries, skills development policies need to be responsive to place-specific characteristics and challenges.

Adult education and training entails a partnership among three parties: governments, employers and individuals. Two fundamental questions need to be answered before any investment can be made: who decides who will receive a certain level of skill development and who will pay for it? The sharing of this decision and the related costs vary over the life course. Governments assume a large portion of costs of early and higher education as well as the costs of education later in life.

Governments in Canada spend significantly on skills development but it is unlikely that they would increase their spending many-fold from current levels. Spending on education tends to be front-loaded, being concentrated on childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. Adult learning in the Canadian system occurs in a number of ways including training on-the-job, formal classroom training, retraining as also returning to school to enhance one’s qualifications or to change one’s skill sets to enter new career paths. A relevant policy issue in this context is to find ways to increase investment in skill development. Each party to this decision faces some constraints but also some creative ways to lever each other’s investments to increase the overall investment. While individual (and family) spending on skills development has gone up considerably in recent decades, individuals often lack information about their options in a fast-changing market for skills. Employers are generally adverse to investment in training unless they have some assurance that they can capture the returns to training. As the Canadian labour market is a relatively flexible market in which talent moves freely across regions, industries and employers, employers are not keen to spend on development of generic skills.

Effective adult education and training requires adequate financing, including incentives for both individuals and employers. Training subsidies, tax incentives and loans, as well as paid training leaves and individual training accounts, can be instrumental in incentivising individuals to contribute to the financing of adult learning. Even small, incremental investments by governments and employers can provide better labour market information and counsel to the individual who, in turn, would be willing to increase their investment in developing their skill sets. Many firms, and especially SMEs, face challenges to financing training, which may lead to under-investments. Two typical types of financial incentives for employers widespread across OECD countries are subsidies and tax incentives: the former include subsidies for workplace training of employees and subsidies to take on and train the unemployed, while the latter include reductions/exemptions in social security contributions. In addition to the training costs, firms face indirect expenses such as continued wage payments during training periods. Some OECD countries have put in place job rotation schemes to help firms find a temporary replacement worker (usually an unemployed person) during the training period to tackle challenges related to foregone productivity during worker absence for training purposes (OECD, 2019).

Box 4.1. Towards a local approach to the future of work: Lesson from Southampton, United Kingdom (UK)

The city of Southampton in the UK recently carried out an extensive inquiry on the future of work in the city. It considered the potential impact of artificial intelligence, robotics and other digital technologies on the Southampton economy, identifying good practices being implemented elsewhere and policies to potentially introduce in the city. Building on the inquiry, the City Council has designed an action plan, to ensure the city and its residents stay ahead of the curve in the digital age.

The inquiry, led by a panel comprised of elected officials, was held between September 2018 and March 2019, to consider how the city could maximise the opportunities created by artificial intelligence (AI), automation and technological changes. At the same time, it aimed to identify and mitigate potential disruption to the local economy, particularly for workers in sectors that are most likely to see the greatest increase in the level of use of AI, automation and technological advancement.

As part of the inquiry, advice and insights from experts as well as local practitioners in other cities were gathered. These were undertaken alongside extensive analysis conducted by a dedicated team at the council to develop a robust business case to shape the city’s future growth. The inquiry identifies the ingredients available in the city and potentially allowing the tech sector to grow and become more vibrant, and institutions and partnerships that could help advance the city’s objectives. A resulting action plan identifies main actions the city plans to undertake in response to the inquiry on the future of work. These include for example the development of a city-wide skills strategy and the update of education curricula to enrich the offer of digital skills, as well as the analysis of the current skills offer of education providers in the city. As part of the strategy, the city also plans to map existing platforms facilitating lifelong learning across Southampton and find ways to improve access, improve rates of progression and increase job outcomes.

Source: Southampton City Council (Getting Southampton ready for the AI revolution, 2019), Getting Southampton ready for the AI revolution, https://www.southampton.gov.uk/news/article.aspx?id=tcm:63-418034 (accessed on 3 February 2020); Southampton City Council (2019), Executive response to the Future of Work in Southampton Inquiry.

4.2.5. Automation creates significant demand for new skills

Lastly, automation is creating demand for some skills and thus creating new jobs even as it disrupts the existing ones (OECD, 2019). Automation’s threat is accompanied by new opportunities that need to be harnessed to create prosperity. Jobs requiring new skills such as big data management, robot engineering and drone operation did not exist a generation ago. Appropriate policy response to the introduction of automation needs to consider how those new skills would be made available to workplaces. Workplaces can also be themselves the generators of new skills, as workers innovate on the job and build new skillset. Specific skills could also be taught on the job and integrated into training programmes.

One important issue pertinent to this assumption is a discussion about the rate at which automation would create demand for new skills and jobs. Notably, the period of automation in agriculture, from the 1880s to the 1920s, saw rapid growth in demand for labour in factories to manufacture cars and other consumer items. During the current round of automation in the last two decades, although the global economy and the number of jobs have grown, automation by itself does not appear to have created enough demand for skilled jobs to compensate for the well-paid skilled jobs that it replaced, resulting in stagnation in employment and wages (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019). Acemoglu and Restrepo (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019) argue that it is necessary to acknowledge that the type of automation adopted would determine if skilled and better-paid jobs would be created in the coming rounds of automation.

While some types of automation would not result in big increases in productivity, other types of automation could spur productivity growth and lead to growing demand for skilled labour. Many new technologies do not increase labour productivity, but are explicitly aimed at replacing it by substituting cheaper capital (machines) in a range of tasks performed by humans. Historically, as automation technologies were being introduced, other technological advances simultaneously enabled the creation of new tasks in which labour had a competitive advantage. This generated new activities in which human labour could be reinstated into the production process and contributed to productivity growth as new tasks improved the division of labour. The episode of agricultural mechanisation, which started in the second half of the 19th century, vividly illustrates this pattern (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019). Looking at the United Kingdom during the industrial revolution in the second half of the 18th century, labour-saving innovations raised profitability of other inputs and therefore the demand for workers producing them. The burgeoning wealth of those profiting from these innovations increased demand for new products and services in a range of sectors, such as more solicitors, accountants, engineers, tailors, gardeners, which created more jobs. In the current wave of automation however there is uncertainty around whether similar dynamics will emerge (Banerjee & Duflo, 2019).

Among other things, meeting the challenge of rapidly developing skills needed to create, adopt and manage these technologies, means that a more agile response from skills development institutions is necessary (OECD, 2019). Colleges and universities or private training providers could shorten the lead time needed to design and offer new courses, while employers bear some of the effort. Funders of these activities such governments and the private sector need a more agile ability to assess quickly what the market needs and how best to mobilize resources, both financial and human, to meet those demands. Any complacency in this regard is likely to result in missed opportunities for creating prosperity. The world today is far more connected and competitive. If the need for new skills is not addressed properly, those opportunities will be grabbed by others, forcing the laggards to the second-tier of progress and prosperity.

4.3. Preparing Canadians for a changing labour market

4.3.1. Both federal and provincial governments are providing support to families and workers during the COVID-19 crisis

The Government of Canada is taking action to support Canadians and businesses facing hardship as a result of the global COVID-19 outbreak. For example, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) provides temporary income support for workers who have stopped working or are earning less than CAD 1 000 in a month due to COVID-19. It grants a payment of CAD 2 000 for a 4-week period for up to 16 weeks. The Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) on the other hand targets employers, providing a 75% wage subsidy to eligible employers for up to 12 weeks, retroactive to March 15, 2020, as a result of COVID-19. Temporary financial support is also being provided for post-secondary students and graduating high-school students (Government of Canada, 2020). Box 4.2 provides an overview of the measures by taken by the federal government in Canada to respond to COVID-19.

Provincial governments are complementing federal efforts, also by focusing on skills development. For example, Ontario has taken steps to support people and families by planning to invest CAD 3.7 billion in support of people and jobs. Measures include among others 200 million in new funding to provide temporary emergency supports for people in financial need and funding to municipalities and other service providers to respond to local needs (e.g. food banks, homeless shelters, churches and emergency services); committing CAD 100 million in funding through Employment Ontario for skills training programmes for workers affected by the COVID-19 outbreak; working with the federal government to find ways to support apprentices and enable businesses to continue to retain these skilled trades workers during the COVID-19 outbreak (Government of Ontario, 2020).

Box 4.2. Federal responses to COVID-19 in Canada

Measures adopted by the Government of Canada to respond to the pandemic crisis include policies and programmes in support of individuals, businesses and specific sectors. Examples of measures targeting individuals include:

Individuals and families: providing temporary wage top-up for low-income essential workers, increasing the Canada Child Benefit, providing extra time to file income tax returns and delaying mortgage payment;

People facing loss of income: Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB);

Indigenous people: supporting immediate needs in Indigenous communities, Indigenous communities public health needs and post-secondary students;

People who need it the most: improving access to essential food support, supporting people experiencing homelessness and women and children fleeing violence, delivering essential services to those in need;

Seniors: including through support to the delivery of items and personal outreach and providing essential services to seniors;

Youth, post-secondary students and recent graduates: Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB), expanding existing federal employment and skills development programmes, including the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy and Student Work Placements programmes, as well as new temporary flexibilities for the Canada Summer Jobs program to allow employers to support up to 70 000 job placements for youth in 2020-21.

A range of programmes have been adopted to support business and workers, including:

Avoiding layoffs and rehiring employees: implementing the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), and a temporary 75% wage subsidy for up to 24 weeks;

Access to credit: among others, by establishing a Business Credit Availability Program (BCAP) to provide additional support through the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) and Export Development Canada (EDC);

Creating new jobs and opportunities for youth: as mentioned above, as part of the supports for youth, students and recent graduates, the Government of Canada announced an additional CAD 153.7 million in funding for the Youth Employment and Skills Strategy to create over 6 000 job placements and supports for youth in high-demand sectors such as agriculture, technology, health and essential services, as part of its response to address the economic impacts of COVID-19 on student and youth employment;

Taxes and tariffs: providing more time to pay income taxes;

Support for workers not covered or eligible for Employment Insurance: Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB);

Indigenous businesses: allocating funding for Indigenous SMEs and Financial Institutions;

Supporting financial stability: for example through the Bank of Canada’s actions and by launching an Insured Mortgage Purchase Program.

Finally, the Government of Canada has also taken measures in support of sectors particularly affected by the crisis. These measures generally aim at protecting workers, ensuring the continuity of supply chains and waiving payments. Interested sectors include agriculture, agri-food, aquaculture and fisheries; culture, heritage and sport sectors; air transportation; tourism; and energy.

Source: Government of Canada (Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan , 2020), Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html#businesses (accessed on 14 May 2020).

4.3.2. More action is being taken at the federal level to prepare for the future of work

In the area of labour market policy, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) manages a number of programmes and services that are designed to help people prepare for work. Prominent examples include loans/grants for students and apprentices as well as Indigenous programs, and youth/student/WIL initiatives. ESDC also administers the Employment Insurance programme, which is a national programme, funded through employer and employee contributions, that offers temporary financial assistance to qualified workers who have lost their job (OECD, 2014). In terms of activation policies, the centrepiece of the federal government’s policies and programmes is covered through the Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs) and Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs), which are bilateral agreements negotiated with the Provinces and Territories.

Each year, the Government of Canada invests over CAD 2 billion through the Labour Market Development Agreements and about CAD 1 billion through the Workforce Development Agreements, for a combined investment of around CAD 3 billion a year. The former are geared towards training and employment assistance for individuals who qualify for Employment Insurance. The relatively new Workforce Development Agreements seek to help individuals who are further removed from the labour market, unemployed, underemployed, and seeking to up-skill to either find a good job or reorient their career. This agreement would include funding for skills training for individuals who are generally not qualified for Employment Insurance.

Outside of these agreements, ESDC runs a number of programmes aimed at skills development in general, with some specialised programmes aimed at targeted population segments, such as Indigenous People, immigrants, persons with disabilities and older workers (OECD, 2014) (OECD, 2018). While the development of employment and skills policies takes place at both the federal and provincial level in Canada, the federal government has introduced a number of programmes designed to respond to the future of work. For example, Future Skills is part of the Government’s plan to ensure that skills development policies and programmes are prepared to meet changing needs. The Canadian Government is investing CAD 225 million over four years, starting in 2018, and CAD 75 million per year thereafter, to:

examine major trends that will have an impact on national and regional economies and workers;

identify emerging skills that are in demand now and into the future;

develop, test and evaluate new approaches to skills development; and

share results and best practices across public, private and not-for-profit sectors to support broader use of innovative approaches across Canada.

As part of Future Skills, the Future Skills Council provides advice to the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion on emerging skills and workforce trends. The Council identifies and promotes priorities for action of pan-Canadian significance relating to skills development and training. The council plays a role in mobilising action across sectors on the issues of pan-Canadian significance they identify. Future Skills also includes the Future Skills Centre, which is an independent innovation and applied research centre that has been set-up to develop, test and measure new approaches to skills development. Future Skills places a focus on addressing the needs of disadvantaged groups, such as Indigenous People, persons with disabilities, workers with low income, immigrants and youth (see Box 4.3) notably by applying a gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) approach recognising that different approaches are needed to meet the needs of a diverse population geographically and demographically. Future Skills places a strong emphasis on ensuring the evidence produced by the Centre and the Council is widely disseminated.

Box 4.3. Testing local approaches through the Future Skills Centre in Canada

The Future Skills Centre is investing in local community-based projects that are testing innovative approaches to skills across Canada. Currently, there are 46 innovation projects and 4 strategic initiatives that have been funded. Sixteen of these projects are operational. In addition, the Centre is launching a new call for innovation proposals in response to the COVID crisis. Each project will be evaluated using tools and approaches aligned to their unique goals and local context but using a unique evaluation framework to ensure consistency and reliability of the Future Skills Centre’s project findings. Some examples of innovative projects that have been funded include:

Up-skilling displaced workers in Kitchener and Toronto: Mold-making and injection-molding companies in the Kitchener-Waterloo and Greater Toronto Areas report a severe shortage of experienced, skilled workers to fill job vacancies. The Work-Based Learning Consortium (WBLC) is partnering with Canadian Association of Mold Makers to explore how to up-skill displaced workers, providing them with the training required to fill vacancies in the mold-making trade and injection-molding occupations in the Greater Toronto Area (including Oshawa) and the Kitchener-Waterloo areas. The Future Skills Centre is investing CAD 873 300 in this 20-month project. The programme will evaluate the effectiveness of a model to help transition 24 mid-career workers into new careers. The model is a worked-based learning competency-based and circumvents traditional CV and qualification-based recruitment approaches and has proven successful in other population groups. The project will take place in two stages: 1) Competencies for the target job will be mapped, candidates who have been displaced (or are at risk of being displaced) will be identified and referred for interviews; and 2) successful candidates will go through digitally-delivered classroom learning to acquire the basic theoretical knowledge and on-the-job training to obtain an industry-recognised credential.

Dementia training for mid-career workers in London: Personal Support Workers (PSWs) are a vulnerable group of health care providers – they are mostly female, over the age of 40, mid-career, and often with English as a second language. Many PSWs have transitioned from other careers and have multiple jobs. Few have received adequate dementia skills development training. Researchers at Western University’s Sam Katz Community Health and Ageing Research Unit developed ‘Be EPIC’, a two-day dementia-specific skill development program. The training programme teaches PSWs to use person-centred communication, incorporate social history of clients into care routines, and use the environment when caring for people living with dementia. The Future Skills Centre will invest CAD 418 717 over two years to test, and evaluate the effectiveness of the Be EPIC training programme in different context. Be EPIC will engage 48 participants in an urban setting (London, Ontario) and a rural setting (Northumberland County, Ontario). By leveraging virtual reality technology, the programme allows PSWs who are culturally and linguistically diverse to gain the skills necessary to relate to people living with dementia and provide quality care.

Digital competencies project: Due to rapidly shifting digital skills needs, a mismatch exists between the skills of many post-secondary graduates and the technical skills required by employers. These digital skills often include a combination of innovation, entrepreneurship, an understanding of the technology adoption processes, and soft skills, including communications, creativity, and adaptability. The Future Skills Centre will invest CAD 1.24 million in a two-year project led by the Information Technology Association of Canada (ITAC), which explores new approaches to defining digital competencies and creating new pathway opportunities into digital roles for non-STEM graduates, internationally-educated professionals, and high-potential workers without traditional credentials. This subsidised project delivers skills training in a heavily-blended approach for digital and professional competencies. ITAC, along with member companies and partners, will work to define a set of in-demand, innovative digital competencies. Using this knowledge, the curriculum will be developed and tested for alternative pathways into digital roles. Rigorous skills testing and aptitude assessments will be a key component of this project. This project will target 370 job seekers and employers in Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia.

Source: Examples summarised from Future Skills Centre (Innovation Projects, 2020), Innovation Projects, https://fsc-ccf.ca/innovation-projects/.

4.3.3. Actions are also being taken to provide support to individuals making labour market transitions

Individual learning schemes are training schemes attached to individuals (rather than to a specific employer or employment status), which are at their disposal to undertake continuous training along their working lives and at their own initiative. The goal of these schemes is to boost individual choice and responsibility concerning training. A characteristic of such schemes that has made them attractive, given the current changes and disruption in the labour market, is their ability to make training rights “portable” from one job or employment status to the other, thereby linking trainings to individuals rather than to jobs. The OECD has recently undertaken a review of the existing individual learning schemes, developing recommendations on how such schemes should be developed to ensure they are effective (see Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. Designing effective Individual Learning Schemes

A rise in non-standard work across the OECD and an increased fragmentation of worker careers have generated new challenges for training policies, at a time when structural changes are increasing the need for re- and up-skilling. Policy makers are searching for new solutions to the challenges related to the future of work, and individual learning schemes have received renewed attention. Individual learning schemes can take different forms, consisting for example of individual saving accounts for training (where the individual can accumulate resources for further training), individual learning accounts (where rights for training are accumulated over a certain period of time) or voucher schemes (supporting training through direct governmental payment to individuals). The OECD has articulated some principles that should guide the development and design of individual learning schemes, to ensure they attain the desired targets. These include:

Targeting individual learning schemes could help improve participation of low-skill workers.

Funding should be substantial if the scheme is expected to make a significant difference to training outcomes.

Individual learning schemes should be kept simple in order to maximise participation.

Individual learning schemes need to be accompanied by other measures to boost participation among under-represented groups.

Guaranteeing training quality becomes even more important in the case of individual learning schemes; and

The way individual learnings schemes are financed has important implications for redistribution and the predictability of funding.

Source: (OECD, 2019), Individual Learning Accounts: Panacea or Pandora's Box?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/203b21a8-en.

The Government of Canada has recently announced the Canada Training Benefit (CTB), a programme aiming to help workers re-skill and up-skill in a changing world of work. The CTB would give workers a refundable tax credit on their income tax and benefit return to help offset tuition costs for training, provide income support during training, and offer job protection so that workers can take the time they need to keep their skills relevant and in-demand. The CTB complements existing skills development programmes in Canada, such as Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs) and Workforce Development Agreements (WDAs), and fills a gap identified by the 2018 Horizontal Skills Review which found that unemployed Canadians receive a broad range of supports to acquire or develop new skills but that working adults in mid-career could benefit from more support (Department of Finance, 2019). The benefit would includes:

A new, non-taxable Canada Training Credit to help Canadians with the cost of training fees paid to a university, college, or other educational institution for courses at a post-secondary level or occupational skills courses. Eligible Canadian workers between the ages of 25 and 64, earning between CAD 10 000 and the top of the third tax bracket (around CAD 150 000 in 2019) would accumulate a credit balance at a rate of CAD 250 per year, up to a lifetime limit of CAD 5 000. The credit could be used to refund up to half the costs of taking a course or enrolling in a training program.

A new Employment Insurance Training Support Benefit to provide workers with up to four weeks of income support, paid at 55% of average weekly insurable earnings, to be taken within a four-year period when they require time off work to train;

A new leave provisions under the Canada Labour Code that would allow workers whose employers are in the federally regulated private sector to take time away from work to pursue training and receive the EI Training Support Benefit without risk to their job security.

Box 4.5. How are individual training schemes being implemented in other countries?

Compte Personnel de Formation, France

Among individual learning schemes, the French Compte Personnel de Formation (CPF) is frequently cited as an interesting new approach which could boost participation in the new world of work, and the only example of individual learning account in the world. Introduced in 2015 to replace an earlier training account (Droit Individuel à la Formation), the CPF is available for all labour force participants and it is financed through a compulsory training levy on firms.

The CPF is a virtual, individual account in which training rights are accumulated over time. It is virtual in the sense that resources are mobilised if training is actually undertaken. As part of the programme, individuals get EUR 500 per year, capped at EUR 5 000 in the standard case, and training programmes are required to deliver a certificate.

The CPF has involved 627 205 participants in 2018 or 2.1% of the labour force.

SkillsFuture Credit, Singapore

Introduced in 2016, the SkillsFuture Credit is a lifetime voucher available to all citizens aged 25 and above, and it is financed through general taxation. Eligible Singaporean citizens receive an opening credit of SGD 500, without time limits, and the government provides periodic top-ups. The credit can be used on top of existing government course subsidies to pay for a wide range of approved skills-related courses, including online courses, subsidised or approved by SkillsFuture Singapore. These include selected courses offered by Ministry of Education-funded institutions, including the Institute of Technical Education, polytechnics, autonomous universities, Singapore University of Social Sciences, LASALLE College of the Arts and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. The SkillsFuture Credit has involved 431 000 participants over 2016-18 and 146 000 in 2018, respectively 12% and 4% of the labour force.

Source: OECD (2018), Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2019: Towards Smart Urban Transportation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/saeo-2019-en.; SkillsFuture (2019), SkillsFuture: 2018 Year In Review, https://www.skillsfuture.sg/NewsAndUpdates/DetailPage/a35eccac-55a5-4f37-bd2f-0e082c6caf70 (accessed on 14 January 2020).

4.4. The Province of Ontario is focusing on supporting labour market transitions

4.4.1. Employment Ontario is under reform to make it more responsive to individual workers and firms

Employment Ontario is the employment and training system primarily managed by the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development. It was created through the integration of a variety of federal and provincial programmes through the 2007 Canada-Ontario Labour Market Development Agreement. Employment Ontario is responsible for policy directions for employment and training; setting standards for occupational training, particularly for trades under the Trades Qualification and Apprenticeship Act; managing provincial programmes to support workplace training and workplace preparation, including apprenticeship, career and employment preparation, and adult literacy and basic skills; and, undertaking labour market research and planning.

Employment Ontario is currently at the frontlines of providing workers with skills development opportunities in light of COVID-19. The Government of Ontario has committed CAD 100 million in funding through Employment Ontario for skills training programmes for workers affected by the COVID-19 outbreak (Government of Ontario, 2020).

Employment services are delivered in part through a network of 170 contracted service providers with over 400 service delivery locations across Ontario (OECD, 2014). The Ministry manages the delivery of programmes and services through four regional branches and a network of local offices. Through Employment Ontario, individuals have access to client service planning and co-ordination; resource and information; job search; job matching, placement and incentives; and, job training and retention services. In general, two levels of service are provided: unassisted and assisted. For unassisted services (i.e. self-services), any person entering an employment service provider office will have access to job search assistance, such as filling out applications or completing a curriculum vitae. Assisted services are provided to individuals who require more intensive services in finding a job. While service providers have considerable latitude in organising counselling and placement services for training programmes, they recommend courses for clients to a training consultant (any provincial government employee) who reviews and approves the application.

The Ontario government has recently announced that it is moving ahead with the reform of the employment services system by introducing new Service System Managers in three prototype regions across the province. This approach will aim to create an efficient employment service to meet the needs of all people, including those on social assistance or with a disability; be more responsive to local labour market needs; and deliver results for job seekers, employers and communities (Ontario Government, 2020). The new employment services model was first implemented in three prototype regions: Region of Peel, Hamilton-Niagara and Muskoka-Kawarthas. A new competitive process open to any public, not-for-profit and private sector organization was launched to select Service System Managers for the three prototype regions (Ontario Government, 2020).

4.4.2. Ontario has an established structure of local boards that work at the community level

Workforce Planning Ontario, a network of workforce planning boards launched in 1994 has the mandate to connect stakeholders within the labour market. Workforce Planning Ontario include a network of 26 Workforce Planning Board areas covering four regions across the province. Each Workforce Planning Board gathers intelligence about the supply of labour and the demand of skills within their local labour market by working with employers to identify and meet their current and emerging skills needs. The primary role of Workforce Planning Boards is to help improve understanding of and coordinate local responses to labour market issues and needs.

As an example, established in 1997, Workforce Planning Hamilton (WPH), a non-profit, is one of 26 Local Boards in Ontario. Its Board is governed by members drawn from business, labour, education, and community representatives from various groups such as women, aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities, visible minorities, and francophone, among others. WPH undertakes the following activities:

Profile the trends, opportunities, and priorities of Hamilton's labour market

Identify skills shortages and future training requirements

Share research with the community to promote labour force planning and training

Undertake projects and partnerships that address labour force issues

WPH conducts, as do other Workforce Planning Boards in Ontario, the annual Employer One survey, which queries employers in the region regarding their current and future hiring needs. Results are published on their website. In 2019, 326 employers completed the survey, an increase of almost 50 employers from the previous year.

In addition to the Workforce Planning Boards, the Ontario government announced the establishment of Local Employment Planning Council pilots. These councils were announced in 2015 with the goal of promoting place-based approaches to workforce development, while generating and analysing local labour market information. The ministry is piloting LEPCs in eight communities: Durham, London-Middlesex-Oxford-Elgin (see Box 4.6), Ottawa, Peel-Halton, Peterborough, Thunder Bay, Timmins, and Windsor. Both the Workforce Planning Boards as well as the Local Employment Planning Council pilots conduct localised research and actively engage organisations and community partners in local labour market projects. However, their role is mostly limited to gathering and disseminating labour market information – they generally do not manage or delivery employment and skills development programmes.

The Ontario Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development is making active efforts to ensure that the local boards have access to critical programme information to inform their local labour market planning. For example, the Ministry shares aggregate activity reports on a number of government programmes, such as Apprenticeships, Employment Services, Literacy and Basic Skills, Ontario Employment Assistance Services, Second Career, and the Youth Job Connection programme. The data is shared with the Local Boards, Local Employment Planning Councils, and other regional networks to identify potential gaps or duplications in service within their catchment areas and provide insight into better engaging disadvantaged groups.

Going forward, evaluating the work of the Workforce Planning Boards, and using the findings of the evaluations of the Local Employment Planning Councils pilot project in informing decision-making, and taking corrective action where needed, could help ensure their effectiveness. In January 2017, the councils began reporting labour market information to the Ministry on a quarterly basis. The Ministry had concerns with the information provided and the councils’ ability to build local labour market information capacity. For example: some reports/products contained limited analysis and interpretation; considerable number of reports repackaged Statistics Canada data with little analysis and did not appear to add to the body of evidence on local labour market needs; engagement with employers was uneven across the councils. While some councils were relatively strong in engaging employers, in most cases there was limited involvement with employers; issues with data collection techniques such as using open-ended survey questions that were difficult to analyse and interpret, and sampling methods and response rates were unclear.

The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO) is an agency of the Government of Ontario that brings evidence-based research to the continued improvement of the post-secondary education system in Ontario. As part of its mandate, HEQCO evaluates the post-secondary sector and provides policy recommendations to the Ministry of Colleges and Universities to enhance the access, quality and accountability of Ontario’s colleges and universities. The Council reports to the Ontario Minister of Colleges and Universities and must prepare an annual report, which it submits to the Minister for tabling in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario (Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario). HEQCO recently completed two large-scale trials involving more than 7 500 students at 20 Ontario universities and colleges to measure literacy, numeracy and critical-thinking skills in entering and graduating students. Findings include that one-quarter of graduating students score below adequate on measures of literacy and numeracy. Based on the findings, HEQCO recommends that such assessments be implemented across all institutions and involve all students, rather than just a sample, and that they be integrated into programme requirements (Higher Education Quality Control of Ontario, 2018).

Box 4.6. Local actions being taken by the Local Employment Planning Council in London, Ontario

In December 2015, the Elgin Middlesex Oxford Workforce Planning and Development Board was selected by the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities to pilot the Local Employment Planning Council (LEPC) project for the London Economic Region, which includes Middlesex, Oxford and Elgin County. Activities are governed by a Central Planning Table that is comprised of stakeholders in the London Economic Region from a variety of sectors. In addition, there are several working groups: 1) Employer Engagement, 2) Service Planning, and 3) Intergovernmental /Inter-ministerial partnerships. The LEPC aims to create a network of employers, service providers, educators and government officials to address the needs of the local workforce. The LEPC supports the following activities:

Labour Market Information and Intelligence: The LEPC aims to expand the current understanding of local labour market issues while improving access to labour market information resources.

Integrated Planning: The LEPC aims to serve as a central point of contact and facilitator for linking employers, service providers, and other levels of government to identify and respond to labour market and workforce development challenges and opportunities.

Service Coordination for Employers: The LEPCs aims to act as a hub for connecting employers, industry associations, sector groups and other employer groups with appropriate employment and training services to address their workforce development needs. Working with local employment and training service providers, including those outside the Employment Ontario network such as Ontario Works Employment Assistance and Ontario Disability Supports Program – Employment Supports, the LEPC co-ordinates services to employers, such as job development and job placements.

Research and Innovation: The LEPC collaborates with community stakeholders to develop projects related to the research and piloting of innovative approaches to addressing local labour market issues.

Sharing Best Practices and Promising Approaches: The LEPC works with provincial and community organisations, including other LEPCs, to identify and share local best practices that could inform action.

The LEPC also sets bi-annual local development strategies for the economy and the labour market of the London Economic Region. Among the innovative initiatives proposed by the LEPC, there is a section of the council’s website that is devoted to reality checks. The LEPC has reached out to local businesses to find out what may be stopping people from finding work and businesses from finding employees. It has then collected a list of statements on the current situation of the labour market in London as well as national and global trends, marking them as “facts” and “myths” providing explanations and resources to educate the community about the regional labour market.

Source: Local Employment Planning Council (2020), Local Employment Planning Council website, http://www.localemploymentplanning.ca/ (accessed on 14 January 2020); Oxford Workforce Development Partnership (2018), Local Employment Planning Council (LEPC): London Economic Region (LER).

Box 4.7. Establishing local boards or facilitators: How do other OECD places do it?

Many OECD countries are looking for opportunities to promote more place-based responses to employment and skills training. The type and nature of local response varies with some countries providing more autonomy to the local level in actively deciding on the management and delivery of programmes and services.

United States

There are over 600 Workforce Investment Boards (WIBs) that are responsible for providing employment and training services within a specific geographic area. The number of WIBs within each state varies by population, geographic size and a state’s approach to providing services. The federal legislation, the Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act requires that at least 50% of the WIB members come from local firms in a community, which helps to ensure that each board is demand driven.

Australia

Australia has recently established Employment Facilitators which are contractors of the Department of Education, Skills and Employment with an on the ground presence that work with displaced workers and other job seekers to connect them with training, job opportunities and other supports. Employment Facilitators aim to establish strong connections with firms in their region, while also working with local employment service and training providers to improve connections between job seekers and those firms looking for workers.

United Kingdom

There are 38 Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEP) currently operating within England. A LEP plays a central role in deciding local economic priorities and undertaking activities to drive economic growth and create local jobs. A LEP is overseen by a Board which is led by a business Chair and its board members are local leaders of industry (including SMEs), educational institutions, and from the public sector.

Source: OECD (2020), "Better using skills in the workplace in the Leeds City Region, United Kingdom", OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2020/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a0e899a0-en; OECD, (2019), Indigenous Employment and Skills Strategies in Australia, OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dd1029ea-en; and OECD (2014), Employment and Skills Strategies in the United States, OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209398-en.

4.4.3. Helping communities make labour market transitions into growing sectors

In general, an important strength in the Ontario education and training system are the strong linkages that exist across local institutions. These linkages translate into collaborations across education, industry, government and community organisations. Local boards such as workforce planning boards and economic development boards provided focal points for problem-solving at the local level. As an example of such collaborations, Communitech is an unusual community organisation that formed in response to the emergence of a digital technology hub in the Kitchener-Waterloo area. It combines resources from several local organisations to offer a range of services for enterprises in the region. One such service is to help fast-growing tech companies find mid-career talent in other industries.

Communitech has been working with employers to develop career paths that would take mid-career people from industries more vulnerable to disruption to the technology-driven firms and industries. Demand for certain skills in technology firms has been growing even as some other sectors have been declining. This therefore creates a scenario that could help re-allocate labour from one sector to another. These transitions are however not necessarily smooth, as it is not immediately apparent how people from industries more vulnerable to disruption could easily port their skills to technology-driven newer firms. From a survey of employers in the Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge region, Communitech in collaboration with the Brookfield Institute of Ryerson University, identified a set of seven job families that were in high demand in the tech sector but could be found also in other industries. These job clusters were software development, artificial intelligence, data science, sales and marketing, production management, user experience, and business management skills for the tech sector (Tibando & Do, 2018).

These job families are then used to identify potential talent for recruitment from other industries. Communitech uses these job families to offer employers a range of services to recruit. The survey revealed that tech employers in the region have been successful in talent acquisition from other industries at the mid-career level. Survey findings also suggest that mid-career workers holding a wide range of jobs in older industries are an under-utilised opportunity for tech employers.

Box 4.8. Increasing awareness of the importance of digital technology at the local level: Communitech, Kitchener, Ontario

Communitech was founded in 1997 by a group of entrepreneurs committed to making the Kitchener-Waterloo Region a global innovation leader. Today, Communitech is a public-private innovation hub that provides resources to more than 1 400 companies — from start-ups to scale-ups to large global players. Communitech’s work shows that there is an opportunity for tech employers to seek out people making or considering mid-career transitions and help is available to firms who reach out. A major takeaway from local networks is that institutional linkages need to be dense and strong at the local level to facilitate efficient and agile response to changing demands of the marketplace. Without these networks, local institutions risk being isolated and unable to mobilise resources in a co-ordinated way to solve skills development challenges.

Communitech provides tools to enhance talent strategy from the recruitment process through to employee engagement and development; a platform for firms to exchange ideas on innovation; consulting help in a variety of ways including Peer2Peer groups; marketing products in domestic and international markets; as well as help to tech workers about their own careers.

Source: Communitech (Communitech website),, http://www.communitech.ca/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

4.4.4. Supporting mid-career workers especially in the manufacturing sector to develop new skills, while ensuring other workers are not left behind

This OECD report has demonstrated that the manufacturing sector is particularly vulnerable to job losses as a result of automation. Automation provides both threats and opportunities – on the one hand, some communities with a strong manufacturing sector will continue to face a risk of losing jobs to automation. The opportunity is that automation enables local firms to offset potential skills shortages and become productive over time.

From 2008 to 2019, the manufacturing employment share in Ontario fell from about 13.4% of total employment to slightly more than 10%. One of the government responses to this change was the introduction of the Second Career programme in Ontario by the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development. Second Career is for laid-off unemployed workers for which skills training is the most appropriate intervention to transition them into high-skill, demand occupations in the local labour market. The programme is targeted to recently laid-off unemployed workers to get new skills. Eligible participants can received up to CAD 28 000 for costs include tuition; books; manuals, workbooks or other instructional costs transportation; basic living allowance (maximum CAD 410 per week); and childcare. Individuals receive occupationally-specific skills training or literacy and basic skills training to prepare them for more advanced training.

Looking at the local level in Ontario, the City of Hamilton is known as the “rust belt” of Ontario because of the strong presence of manufacturing jobs. The manufacturing sector represents 12.4% of the city’s employment. The city has focused on building an Advanced Manufacturing cluster to build on its manufacturing history. This includes the following:

The establishment of a McMaster Automotive Resource Centre – This new, 70 000 sq. ft. facility allows private and public sectors to collaborate to develop, design and test hybrid technology. The facility includes a state-of-the-art commercial garage housing multiple bays for automotive testing. Engineers, scientists, social scientists and students develop sustainable technology and business solutions for the auto industry. The site houses an Electric Vehicle R & D Centre; Centre for Mechatronics and Hybrid Technologies; Canadian Excellence Research Chair in Hybrid Powertrain Program; McMaster Materials Research Institute and the Bachelor of Technology Program; and

The CanmetMaterials Laboratory is a research centre dedicated to structural metals and alloys, materials design, pilot-scale processing and performance evaluation. Scientific and technical staff research and development provide materials solutions for the energy, transportation and metals manufacturing sectors.

While support for the manufacturing sector is important, it will be necessary to ensure that policies and programmes do not emphasise this at the expense of providing support to those outside of manufacturing. This is an important consideration with respect to gender equity. Women will be as affected as men with respect to displacement, yet in less visible fields. If some programmes are targeted, such as to manufacturing, where men make up the majority of workers, broader support will be required to ensure other groups do not get left behind.

Box 4.9. Shifting the manufacturing sector into higher value added production: Lessons from the Basque Country in Spain

In 2019, the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) selected the Basque Country’s “Industry 4.0” industrial strategy as a best practice. UNIDO defines “Industry 4.0” as a process in which “the physical world of industrial production merges with the digital world of information technology – in other words, the creation of a digitized and interconnected industrial production, also known as cyber-physical systems”. Created as part of the Basque Government’s 2017-2020 industrial policy, the strategy is meant to create positive conditions for the Basque industrial ecosystem with the objective of maintaining industry as a central part of the Basque Country’s economic and social model.

In practice, the strategy involves programs such as BIND 4.0, a public-private start-up incubator that links entrepreneurs with Basque firms. The plan will also assist SMEs in technological training in new manufacturing methods. The strategy came at a time when industrial employment seemed at risk, as the economic crisis had a particularly noted impact on industrial jobs. The Basque Government aims to restore industry’s share in the region’s economy to 25%, and sees industrial development as a means to reduce unemployment, consolidate recovery, raise social cohesion and lift the region’s GDP per capita to 125% of the EU average

Source: OECD (Forthcoming), OECD Reviews on Local Job Creation: Preparing the Basque Country of Spain for the Future of Work.

4.4.5. Providing more training opportunities for low-skill workers to stay relevant in the labour market

The Ontario employment and training system has recently experimented innovative and evidence-based initiatives going in the direction of preparing people for the future of work. For example, the SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot projects aims to support workforce development in identified sectors. It funds partnerships to connect employers with the employment and training services needed to recruit workers with the right skills, and it also supports jobseekers to get into jobs by providing them with sector-specific employment and training services and connecting them to the right employers (Ontario Ministry of Colleges and Universities, 2019). As part of the SkillsAdvance programme, a course was developed specifically aiming to provide low-skill unemployed people with relevant training to get them into jobs. The course, eight weeks in duration, takes cohorts of fifteen at a time and engages them in trainings at Mohawk College to achieve a certification as a production technician for the manufacturing industry. The programme is employer-driven and most graduates of the program find employment easily right after the course ends.

Box 4.10. SkillsAdvance Ontario Pilot

The SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot project is intended to support workforce development in identified growth sectors. It funds partnerships that connect employers with the employment and training services required to recruit and advance workers with the right essential, technical, and employability skills. It also supports jobseekers to obtain employment by providing them with sector-specific employment and training services, and connecting them to the right employers. SkillsAdvance Ontario embodies a sector-focused strategy that takes into consideration the dynamic nature of regional economies and labour markets, as well as the evolving requirements of different industrial sectors. SkillsAdvance Ontario projects provide the ministry the opportunity to test the effectiveness and efficiencies of sector-focused, partnership-based programming.

Source: Ontario Ministry of Colleges and Universities (2019), SkillsAdvance Ontario Pilot, http://www.tcu.gov.on.ca/eng/eopg/programs/sao.html (accessed on 13 January 2020).

The SkillsAdvance programme has been successful in getting low-skill unemployed people to work, but it graduates only 50 persons a year at the local level, meeting only a small portion of the demand for these services. Programmes aimed at supporting unemployed and low-skill people to access basic skills exist in Ontario. For example, Ontario Works runs a programme specifically aimed at the long-term unemployed. However, the programme only admits 15 clients per class, which may not be enough to handle growing caseloads. A programme re-organisation is underway, but it is unclear whether this will result in greater capacity. Ontario has also targeted the need to enhance basic literacy, including basic skills literacy and digital literacy.