This chapter stresses the relevance of managing integrity risks and lays out the essential steps. It further summarises the framework for corruption risk management in the Romanian central government as well as the challenges in its implementation since it was issued in 2018. The chapter takes a behavioural perspective and discusses how such challenges may be caused by heuristics (mental shortcuts or intuitive judgments) and biased decision-making by the individuals involved in the process.

Promoting Corruption Risk Management Methodology in Romania

1. Corruption risk management in the Romanian central government

Abstract

1.1. The relevance of integrity risk management

In public sector organisations, integrity risk management is crucial to prevent corruption and ensure delivery of public services to citizens. Effective internal control and risk management policies reduce the vulnerability of public organisations by guiding officials to adequately assess risks in their duties and develop strategies to manage them. For an integrated control system to work, countries must put in place response procedures for corruption cases and breaches of integrity standards. The OECD Public Integrity Handbook suggests using proactive corruption risk management tools that follow 6 steps (Figure 1.1): identifying risks, assessing their likelihood, evaluating their impacts, developing control measures, monitoring intervention outcomes and the evolution of risks as well as updating the process if new vulnerabilities arise (OECD, 2020[1]).

Figure 1.1. Steps to manage corruption risks

Risk assessments are iterative processes that allow an organisation to understand the enablers and barriers to its objectives (OECD, 2020[1]). Each step is relevant and comes along with its own challenges. To properly identify integrity risks, information and knowledge about the context and past incidents is key. At the same time, an organisation must be able to be sensitive to emerging risks. The assessment of likelihood and potential damage also requires information guidance. For example, a methodology can rely on numeric scores (e.g. 1 to 5) to assess likelihood and impact, or they can use classifications (e.g. low, medium and high). Both likelihood and impact scores can be linked to specific criteria to facilitate the assessment (OECD, 2020[1]).

After both the likelihood and impact of risk materialisation have been identified, the next step is to define how to respond. The completed risk classification enables institutions to focus preventative efforts on the most relevant risk, consequently saving resources where incidents are expected to be less likely and/or the damage less problematic. Strategies for risk mitigation should be designed considering the best practices available as well as the availability of resources to develop new procedures or strengthen monitoring and training. Finally, organisations should clarify who monitors and evaluates the implementation to draw lessons and inform ongoing risk assessments.

In Romania, through Decision 599 of August 2018, the government requires all central public institutions to implement a corruption risk management methodology. Moreover, the Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration has drafted a guide regarding risk management for the local administration (https://www.mdlpa.ro/pages/metodologieidentificareriscuri). The methodology approved by Decision 599/2018 provides guidance on how to identify risks, assess their consequences, develop control measures and monitor their effectiveness. It calls for the creation of a working group, where internal stakeholders can participate and bring their own expertise. However, despite Romania's efforts to promote the methodology's adoption, its use has been uneven, and it is unclear if it has been effective in reducing integrity incidents.

This OECD report builds on and complements other work carried out by the OECD in Romania (OECD, 2023[2]; OECD, 2021[3]). Taking a behavioural approach, it focuses on the implementation challenges of the corruption risk methodology and proposes concrete strategies to increase its adoption. Chapter 1 presents the existing Romanian framework for corruption risk management while discussing challenges to its adoption. The OECD focused mainly on the education and health sectors as well as Stated Owned Enterprises, however, the analysis and recommendations provided apply across the whole public administration. Building from this, Chapter 2 suggests four strategies to improve public officials’ capabilities, opportunities and motivation to identify corruption risks, assess their likelihood of materialisation and subsequently design effective intervention measures.

1.2. The current corruption risk management methodology in Romania

1.2.1. Decision 599/2018 provides a framework for corruption risk management that is aligned with international standards

The Romanian National Anticorruption Strategy (Strategia Națională Anticorupție, SNA) is the core policy document guiding the government's integrity and anti-corruption efforts. The NAS has been regularly updated since the first NAS, which was first published in 2001-2004, with revisions based on external peer reviews and internal consultation processes by the Ministry of Justice. From 2016 to 2020, the NAS focused on creating a standardised methodology for corruption risk management, which was previously implemented as an internal initiative by some ministries.

As a result of the NAS, the Romanian government issued Decision 599 in August 2018. As mentioned previously, Decision 599/2018 requires all central public authorities and institutions to draft corruption risks registers and to evaluate integrity incidents, which enables to establish anti-corruption measures as responses to the risks. This administrative act provides a methodology for evaluating and managing corruption risks, as well as a standard procedure for evaluating integrity incidents. It also includes annexes with guides on how to complete corruption risk and incidents registry formats.

The framework proposed in Decision 599/2018 follows standard practices recommended by the OECD and other international organisations. It was inspired by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which had been applying its own similar procedure since 2014. The corruption risk registry and the integrity incident registry are designed to be complementary. The corruption risk registry is used to record preventive measures (Table 1.1), while the integrity incident registry is a post-evaluation tool to document disciplinary or legal breaches. When an integrity incident is registered by an organisation in the registry, it is used as an input to analyse the incident's causes, describe its circumstances and propose corrective measures. The technical secretariat of the NAS, embedded in the Department for Crime Prevention (Direcția de prevenire a criminalităţii) of the Ministry of Justice, collects integrity reports from each organisation and prepares an annual report that is shared with all and serves as an input for identifying corruption risks in the entities.

Table 1.1. Corruption risk registry template of Decision 599/2018

|

The field of activity in which the risk of corruption manifests |

Risk description |

Cause |

Likelihood |

Impact |

Exposure |

Description of the intervention measure |

Responsibility for implementation |

Deadline / Implementation duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Decision 599/2018.

According to Decision 599/2018, each ministry or central public authority capable of autonomous spending is required to carry out corruption risk assessments and keep integrity incidents registries. To adopt this methodology, the leader of each ministry or public authority, as well as its subordinated units, must create its own working group and issue its own procedures through an internal directive. For example, the Ministry of Education prepares its own corruption risk assessment and incident registries, and all its subordinated universities develop their own assessments and registries that are aligned with the ministry's internal directive.

The composition of the working group varies depending on the size, responsibilities and capacities of the organisation. The leader of each central public authority assigns a group of representatives from each area of the institution to implement the methodology. Where a subordinated authority does not have sufficient staff to form a working group, the corruption risk management process must be carried out by its superior institutions. For regular-sized organisations, the working group must include members of managerial capacities, leaders from integrity, internal control, disciplinary responsibility, internal audit, human resources, internal managerial control, public procurement and financial areas, the ethics advisor or the integrity advisor and any other members assigned by the head of institutions.

After the appointment of the working groups, the methodology suggests that public servants manage corruption risks by implementing the following seven steps, which are to be recorded in the risk registry template (Table 1.1):

1. Risk identification and description: The members of the working group search for activities previously involved in corruption incidents or define fields of activities that may be susceptible to corruption risks based on their experience. While the methodology is not clear on how to select such activities, during interviews public officials pointed out that it refers to the functional areas that support the organisation's mission as well as administrative operations. After these activities or areas are identified, Decision 599/2018 recommends identifying risks using the following sources: integrity incidents, internal audit reports, reports of the Court of Accounts, reports of control authorities, questionnaires to management or coordinators, press articles, complaints, petitions addressed to the institution, and/or court decisions. Following the documentary review, the group describes the nature of the risk and its causes. The review process can be done in a group, but it is usually done by each member of the working group, depending on their area of work, and then their findings are shared in regular meetings.

2. Risk likelihood estimation: The members estimate the likelihood of risk materialisation on a scale of 1 to 3. Level 1 is reserved for identified risks that have not yet materialised but could arise. Level 2 addresses risks where at least one case has occurred in a similar field of activity, but not in their own institution. Level 3 is for risks where at least one corruption case has occurred in their own institution in that field of activity. Where no previous corruption cases have occurred, a set of 15 contributing factors to corruption must be considered for each risk. The risk is deemed higher the more factors are present in that field of activity (Table 1.2).

3. Impact assessment: The working group assesses the magnitude of damage that each risk would generate by its financial or reputational impact on the institution. Members need to consider evidence or make estimates about the potential financial and reputational consequences associated with each corruption risk.

4. Risk exposure: The risk exposure is calculated as the product of the likelihood and the impact of the risk. This result is then assigned a low, medium, or high level. When the activity has a low-risk exposure, the working group should maintain the existing measures. If the exposure is medium or high, new measures must be implemented.

5. Intervention measure design: Decision 599/2018 provides 6 examples of interventions to consider for risk prevention: proposing amendments to legislation, conducting training activities, developing IT systems, implementing new working procedures, conducting periodic audits or control activities, and staff rotation. The head of the working group designates a person responsible for supervising each measure and establishes an implementation timeline.

6. Monitoring and reviewing: The working group must monitor the results of the intervention measures and the evolution of risks once a year. If new corruption risks arise, the members must repeat the entire process and incorporate it into the corruption risk register to determine risk exposure and establish new measures.

7. Update the integrity plan: Every two years, the working group reviews the results of the integrity plan. Based on the feedback, they update the integrity plan and send it to the SNA’s technical secretariat for monitoring.

Table 1.2. Criteria to classify risks according to Decision 599/2018

|

Low likelihood |

Intermediate likelihood |

High likelihood |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Adapted from Decision 599/2018

1.3. Challenges in the adoption of corruption risk management in Romania

Despite the Romanian government's efforts to adopt a standardised methodology for corruption risk management, the OECD fact-finding mission in 2022 found varying levels of implementation of Decision 599/2018. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has further delayed its adoption. Some public officials from Romanian anti-corruption agencies noted that corruption risk management is often seen as a redundant tool by several stakeholders interviewed. These accounts were contrasted by a revision of corruption and incident risk registries from a selection of ministries and their subordinated units.

This uneven adoption of Decision 599/2018 means that while some organisations correctly identify vulnerable activities, describe the risks and propose meaningful intervention measures, others lack comprehension of each step's requirements or do the minimum to comply with the regulation. To amend this, the Ministry of Justice offers support and assistance on demand, e.g. to raise awareness or share good practices. However, according to public officials interviewed, this support is not well known and not often requested.

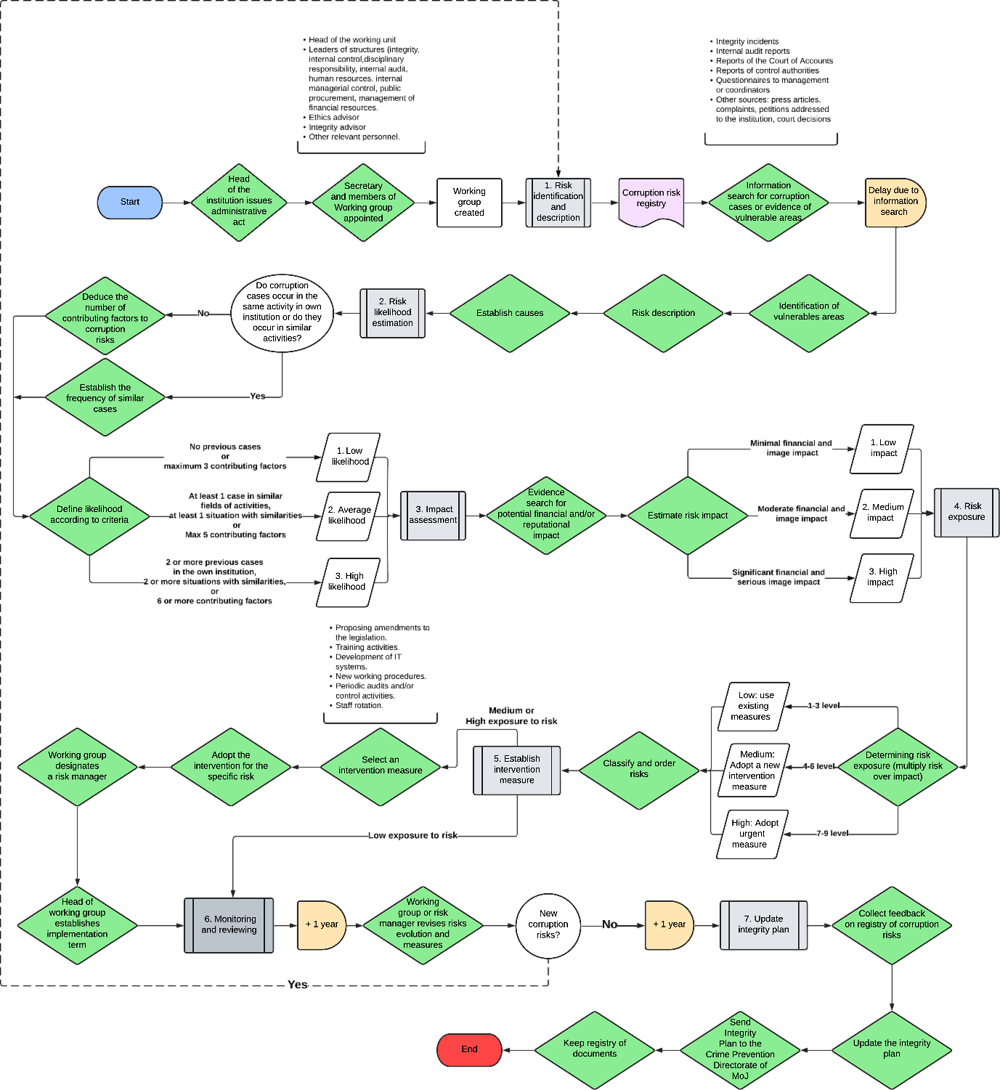

Adoption challenges concerning Decision 599/2018 could result from its complexity. While the methodology proposes seven steps to manage corruption risk, a more detailed analysis by the OECD reveals that it requires substantially more effort and steps, which could explain its uneven implementation. The behavioural flowchart in Figure 1.2 illustrates the explicit and implicit steps needed to logically complete the process. A behavioural flowchart or journey map is tool commonly used in behavioural sciences to understand how easy or difficult it is to enact a behaviour (OECD, 2019[4]). Annex B provides guidance on how to use such flowcharts to map behaviours.

Figure 1.2 depicts each of the explicit seven steps in Decision 599/2018 which are marked by a grey rectangle with a consecutive number. The explicit and implicit behaviours for each step are illustrated by a green rhombus and a white circle depicts a decision point that leads to different risks and impact classification. The process starts and finishes in the blue and red ellipses, respectively, while time delays are shown as yellow half-ellipses.

Figure 1.2. Behavioural flowchart of the Romanian risk management methodology

Source: Based on Decision 599/2018, information provided by the Government of Romania and interviews carried out by the OECD.

In total, the flowchart reveals that there are at least 22 behaviours that must be performed to logically complete the process. These behaviours include gathering and reviewing information, deducing risks from corruption incidents, establishing event causes that are opaque and multi-causal, gathering information to have an awareness of how corruption affects other institutions, predicting the effects of intervention measures and collecting feedback on the evolution of risks, among others.

Given the challenges highlighted in the previous paragraphs, the uneven adoption of Decision 599/2018 is not surprising. As a result, the most common issues with its adoption include inconsistent identification of corruption risks, potential miscalculations of risk likelihood and impact, in addition to poorly designed intervention measures.

1.3.1. The fields of activities of corruption risks are not consistently identified across authorities

After forming the working group, each authority must identify the threats of corruption and vulnerabilities in their “field of activities” (Table 1.1). However, the methodology does not provide a clear definition of what an activity means, nor does it show examples that can be used for guidance. This ambiguity can lead to errors where the context of these corruption risks may be identified as the organisational structure, mission processes, or mission objectives without distinguishing between them.

Organisational structure refers to the arrangement method of a group of people that work towards the same objective (Society for Human Resource Management, 2017[5]), such as the financial or the procurement department. Missional processes are the activities needed to achieve the outcomes of the organisation’s mission. For example, in the case of an educational institution, mentoring is an activity that allows its mission. Lastly, missional objectives are outcomes that an organisation defines to prove it complies with its mission. In the education sector, this could be to increase literacy rates or enrolment in graduate education.

Table 1.3 provides an example of how three different ministries characterise the “field of activities” of their corruption risks. Some institutions use the general and specific objectives of the NAS as a field of activities and then identify risks that prevent their achievement. This leads to examples where the field of activity vulnerable to corruption is the “adoption of the integrity plan”, which is an objective rather than an area vulnerable to corruption risks. In other cases, a risk is related to missional process, such as undue influence in the recruitment activities. Finally, other organisations identify their risk in their organisational structure, such as the Control Body and Public Procurement.

Table 1.3. Examples of field of activities identified in a revision of corruption risk registries

|

Type of context |

Example of the field of activity identified |

|---|---|

|

Organisational structure |

“Public procurement” |

|

Missional process |

“Staff recruitment and selection process” |

|

Missional objective |

“Increasing the degree of anti-corruption education of employees and the impact of corruption on the activity of the ministry” |

It could be argued that the nature of public institutions is very different and that this justifies having an ample definition of "field of activity" that can be adapted to each context. However, a revision of corruption risk registries shows that this creates confusion and lack of uniformity, which can develop into three problems. First, organisations may find it more difficult to learn from each other when some have risks related to objectives while others have risks related to organisational structures. Second, it is more challenging for the SNA's Technical Secretariat to provide feedback for different corruption risk registries that should follow the same methodology. Third, given that this methodology is sequential, if a corruption risk context is incorrectly identified, it may create problems in subsequent steps.

1.3.2. Risk likelihood and impact are not assessed and estimated adequately

The second challenge is related to the assessment of risk likelihood and impact. Corruption risk registries analysed for this OECD fact-finding mission revealed that most organisations assessed their risk with low likelihood and impact, while less examples showed high or medium risk exposure. Underestimating risk exposure can minimise the importance of new effective intervention measures in favour of existing ones. On the other hand, overestimating risks may cause the institution to use more resources than necessary to control certain risks while neglecting those most crucial. Both outcomes are undesired, but with the information currently available on the corruption risk registries, it is not possible to determine if they are correctly or incorrectly assessed.

Decision 599/2018 establishes the following rules to assess the risk likelihood and its impact. To assess the risk likelihood, the working group member must search for evidence of incidents in that field of activity, in their own institutions, or others with similar activities. If none are found, they need to consider at least the 15 contributing factors provided as examples in Annex 2 to Decision 599/2018 and to classify the risks according to their presence in that field of activity. Following that, working group members look for historical evidence or use their experience to match the indicators in the methodology and define if the risk impact is low, medium, or high. In the corruption risk registries reviewed, there is no mention of sources to show that previous incidents or contributing factors were used. The boxes for risk likelihood and impact only show a number. Even if the likelihood is assessed using the information on the incident registry, there is no straightforward manner to evidence if, in fact, it was used for that purpose.

Despite the absence of a clear method to determine if risk and impact are assessed correctly, a potential issue related to human cognitive limitations can be hypothesised. Dual-process theories propose that most human decision-making is performed by quick and effortless actions, not rational reasoning (Kahneman, 2013[6]). When faced with complex decisions, people often use mental shortcuts or make intuitive judgments (heuristics) to simplify their decision-making process and reduce cognitive effort. Such heuristics are often based on past experiences, biases, or generalisations, rather than a thorough analysis of all available information. While heuristics allow people to make decision quickly and efficiently, they can also lead to errors in judgment or biased decision-making when they are used inappropriately (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974[7]). Box 1.1 summarises the framework of dual-process theory and its relationship with heuristics and suboptimal choices.

Box 1.1. Dual process theory, heuristics, and biased decision-making

The dual-process theory is a framework within the behavioural sciences that proposes that human decision-making and reasoning processes are governed by two distinct types of cognitive processes:

Intuitive, automatic processes

Intuitive processes are fast, automatic, and require little cognitive effort. They rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, to quickly assess a situation and arrive at a decision. These processes are often unconscious and emotion-based and can be influenced by biases and past experiences.

Reflective, deliberative processes

Reflective processes, on the other hand, are slower and require conscious effort. They involve logical reasoning and critical thinking and are often used to evaluate the validity of decisions made by the intuitive system. Reflective processes can override or modify the decisions made by intuitive processes and can help to correct biases and errors.

According to the dual-process theory, human behaviour is the result of an interaction between these two types of processes. Intuitive processes are often used to make quick, automatic decisions, while reflective processes are more likely to be used when making complex or important decisions that require more careful consideration.

Because the human brain is limited by the amount and time it needs acquire and process information, people tend to simplify complex situations to make them more manageable. In doing so, they rely on heuristics to overlook important information, causing them to make suboptimal choices. The systematic use of heuristics that leads to flawed decision making is considered a cognitive bias.

Source: (Bazerman and Moore, 2012[8]) and (Kahneman, 2013[6])

As previously mentioned, the behavioural flowchart in Figure 1.2 reveals that 7 steps and 22 behaviours are necessary to adopt Decision 599/2018. The second step, the estimation of risk likelihood, requires group members to perform at least three behaviours: establish the frequency of similar cases to the corruption risk, deduce the numbers of contributing factors to corruption risks and define the likelyhood score according to both previous decisions. The third step, impact assessment, asks them to search for evidence of the financial or reputational impact that a corruption incident has had in the past and to predict the level of damage it could cause.

The complexity of following steps 2 and 3 may lead working group members to use heuristics and simplify their decision-making. These shortcuts could cause them to overlook important information needed to correctly assess the risk likelihood and impact. For example, risk managers may judge that more familiar corruption cases are more probable without considering a broader scope of less known risks (Messick, 2018[9]). The use of this heuristic may drive them to fall prey to the availability bias (Tversky and Kahneman, 1973[10]), where they rely only on easily accessible information rather than reviewing all relevant evidence about corruption and integrity risks. This situation would result in common risks being considered more probable and more impactful, and result in working group members designing new intervention measures only for those risks they remember more easily.

1.3.3. Intervention measures fall into commonplaces and are designed without a clear theory of change and action plan

The implementation of intervention measures also encounters challenges in its design. Many of the reviewed corruption risk registries suggest intervention measures such as unspecified training, recommendations for compliance with existing legislation, staff rotation, periodic audits, or raising awareness of laws or ethical codes. The lack of expertise or knowledge of best practices could explain why working group members employ heuristics to reduce effort, save time, and simplify their decision-making.

As is the case with judging probabilities and impact, the choice of intervention measures can also be biased. Working group members may unconsciously consider only interventions they know and overlook some that are more effective but less familiar. Another possible explanation is that working group members prefer choosing known, “easy” intervention measures (such as “trainings”), rather than trying new ones. This form of status quo bias (Zeckhauser and William, 1988[11]) may explain why the same types of intervention are chosen frequently.

Anchoring could also explain intervention typologies being overly repeated. This cognitive bias leads judgment to be influenced by previous information that should be irrelevant to that choice (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974[7]). The suggestion in Decision 599/2018 to provide only 6 examples of intervention measures may unintentionally contribute to this bias. Because seeking additional information can be time-consuming, working group members might opt to consider only those six examples.

Another challenge in the design of interventions measures is that most of them have unspecified implementation timeframes. The most common term for the interventions reviewed is "permanent" with a few exceptions stating yearly or shorter periods of implementation. This choice of permanent timeframes may hint at two situations. First, that these risks arise in a context where external and internal risk factors cannot be mitigated. Second, it could also indicate that these interventions are being designed with no clear action plan.

The second scenario is more concerning because it implies that intervention measures lack a clear verification method. The corruption risk registry in Table 1.1 does not provide boxes for registering intermediate indicators such as the number of activities completed, the intermediate outcomes, or stating what is the intervention's expected result. The lack of intermediate outcomes hinders the monitoring of whether interventions are effective in managing a given risk. Additionally, it necessitates that authorities seek further evidence to confirm if the interventions have been implemented as stated. On the other hand, without clear indicators, working group members cannot receive feedback on their efforts to control corruption, which, in turn, may decrease their intrinsic motivations to employ time and effort on this task and reduce the ability to learn from their actions (Locke and Latham, 2002[12]).