This chapter proposes four strategies to promote the adoption of the Romanian government’s methodology for corruption risk management. First, the corruption risk register could be redesigned to include intermediate indicators for intervention measures. Second, a user guide for Decision 599/2018 could facilitate its implementation. Third, a web-based app could help to simplify many of the steps involved in corruption risk management. Finally, establishing a dedicated unit within each ministry to assist working groups could strengthen the quality of the corruption risk management process.

Promoting Corruption Risk Management Methodology in Romania

2. Strategies to promote corruption risk management in the Romanian central government

Abstract

2.1. A behavioural theory of change to understand the requirements to execute a specific behaviour

Chapter 1 described the Romanian government methodology for corruption risk management as laid out in Decision 599/2018 and currently implemented in the central government. It highlighted the three main challenges in its adoption and analysed the behavioural aspects that may explain these issues. Building on that, this chapter uses a behavioural change theory to understand what is needed for Romanian public officials to adopt Decision 599/2018 as expected. Following this analysis, the rest of the chapter proposes four avenues to promote its adoption based on behavioural insights.

A behavioural theory provides a framework to understand human behaviour. It sheds light on why individuals engage in certain actions, what factors influence their decisions and how these elements come together to shape people’s behaviour. Theories can also be used to comprehend why an action has not occurred by examining the assumptions that make it possible. An individual cannot play an instrument if he or she does not possess the instrument or have the skills to use it. The same thought process can be used to understand what is needed for a public official to identify corruption risks, predict their likelihood, assess their impact and design intervention measures that can manage these risks.

To promote the adoption of Decision 599/2018 this section uses the COM-B model of behaviour change (Michie, van Stralen and West, 2011[13]) to consider the internal and external elements necessary for such decisions to take place. Box 2.1 explains how behaviours require internal capacities and motivations as well as the existence of external opportunities from the context, and how the interaction between these elements can make behaviours more or less likely to happen.

Box 2.1. COM-B theory of behavioural change

The COM-B is a framework used to understand the determinants of human behaviour. The model states that behaviours are most likely to occur if individuals have the internal capacities (C) to act, are motivated (M), and if the context presents opportunities (O) that support the behaviour.

Capabilities: Physical and psychological internal capabilities that allow a behaviour. For example, to play a sport an individual needs psychical capability in the form strength and musculature for mobility, and psychological capabilities such as knowledge and training to master the skills for these routines.

Opportunities: External opportunities that the physical or social environment provides and that make an action harder or easier to perform. Physical opportunities refer to time and monetary resources, infrastructure or any tangible element that influences the feasibility of a behaviour. On the other hand, social opportunities are the information provided by other people actions on how acceptable or reprehensible an action is. For example, if an individual’s reference group usually speeds thru red-light traffic, she is more likely to follow the same behaviour and to rationalise that it is permissible given that nobody else respects that rule.

Motivation: Internal drives that encourage or create the desire to act. These drives can be via conscious or unconscious cognitive processes. An example of a reflective motivation is an action plan that weights costs and benefits of an action, such as deciding what loan to acquire or how to spend a company’s budget. Automatic motivations are impulses that lead to an action thru emotional responses or habits that do not require people’s full attention. For example, people may avoid an action if it reminds them of a bad situation, produces boredom or has an unpleasant odour or sound. On the other hand, routinely actions such as brushing one teeth or driving are performed even if the individual is not actively thinking of how is done.

The model proposes that the three elements’ interactions influence the chances of a behaviour taking place. For example, when the context provides more opportunities for a behaviour, via less friction or more social examples, people could feel more motivated to do it. Another case could be when people train themselves for an action, they could also sense they do it better and become more motivated.

This model's practicality lies in offering a comprehensive approach to consider the requirements for performing a behaviour and suggesting changes to address any missing elements. For example, if an individual does not know how to do an action more training may be needed. On the other hand, if people don’t have the time to complete a demanding task a tool should be developed to facilitate the action. Finally, if people find a task boring the context could provide more opportunities in the form of rewards aligned with people’s preferences.

This analysis focuses on four of the seven explicit steps to manage corruption risks proposed by Decision 599/2018: risk identification and description, risk likelihood estimation, risk impact assessment, and intervention measure design. The steps are prioritised because they demand working group members to consider more information and exert greater cognitive effort than the others (Figure 1.2). Additionally, they produce more spill overs on the whole methodology. If risks are correctly identified, public officials would have more clarity for defining risk likelihood and impact. Similarly, if the risk likelihood and impact are assessed correctly, the need to design new interventions or keep existing ones could be correctly calibrated. Finally, if interventions measures are designed according to best practices and a clear action plan, the chances to mitigate or control risks will increase.

Using the COM-B lens to analyse the behaviours in Figure 1.2’s flowchart, Table 2.1 summarises what is needed to enable the prioritised behaviours. To identify corruption risk, public officials need knowledge of their own and similar institutions and access to information related to corruption incidents or potential risks. They should be able to deduce risks from corruption incidents and conduct comparative analysis between other institutions and their own. Public officials should recognise the positive impact of risk identification on reducing corruption risks. They also need easy access to relevant information, time to process it, spaces for sharing knowledge and learning and a willingness to spend time on this task. Development of habits such as reading about corruption regularly can create a favourable mental state for risk identification.

To estimate the risk likelihood, working group members need similar capabilities, opportunities, and motivations as in risk identification, but they also require searching for formal and informal evidence on the 15 contributing factors that increase the likelihood score. The assessment of the impact if a risk materialises has coinciding needs. In this case, working group members need historical information on the impact of integrity incidents or to be able to use the criteria in Decision 599/2018 to predict the expected damage.

Finally, to design effective intervention measures, working group members need to understand how anti-corruption strategies work and have opportunities to learn and share information about best practices in this subject. They also must feel that their efforts have an impact on risk reduction on their own reputation and the institution’s reputation.

Based on the analysis carried out by the OECD, Table 2.1 provides an overview of capabilities, opportunities and motivations required in four key steps: the identification and description of risks, the estimation of the likelihood of risks, the impact assessment of the risks and the design of intervention measures. In short, working group members need to possess substantial capacities, sufficient opportunities and ample motivations to perform those four steps. However, during interviews and focus groups with Romanian public officials, it was noted that working group members frequently rotate in and out of office, making it unlikely that they already possess the necessary abilities. Newly hired working group members may not know the formal and informal practices that increase corruption risks, and unexperienced public officials would need more opportunities to catch up and use their time to review corruption incidents, participate in sharing activities, and learn from best practices in corruption risk management. Even if staff rotation is not a widespread issue, the time required to acquire those abilities could be substantial for public officials. The lack of abilities and opportunities may decrease their motivation to correctly adopt Decision 599/2018 and lead them to use heuristics. Those shortcuts would simplify their decision-making but result in compliance with the bare minimum.

Table 2.1. Prioritised steps and what is required to enact each step

|

Capability |

Opportunity |

Motivation |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Risk identification and description |

Knowledge of the institution’s functions and procedures. |

Access to all relevant information sources. |

Working group members must have a strong desire to review all relevant information and to accurately describe corruption risks within their own institution. |

|

Estimation of likelihood of risks |

Awareness of integrity incidents and other internal or external sources that highlight vulnerable areas. |

Time to review all relevant information and sources recommended in Decision 599/2018. |

Members must be aware of the consequences of not properly identifying corruption risks. |

|

Risk impact assessment |

The ability to deduce risks from corruption incidents. |

Spaces to share risk identification and descriptions with members of similar institutions. |

Developing the habit of being vigilant towards corruption incidents. |

|

Intervention measure establishment |

Capacity to perform comparative analysis between the institution and knowledge on anti-corruption measures. |

Assistance from members with expertise in corruption risk identification. |

Working group members must have a strong desire to review all relevant information. |

2.2. Four behavioural-informed strategies to promote the adoption of the corruption risk management methodology

The Romanian government could consider four avenues to increase the adoption of the corruption risk management methodology:

Redesign the risk registers to include intermediate indicators for intervention measures.

Design a user guide for the adoption of corruption risk methodology in Decision 599/2018.

Develop a web-based application to guide the management of corruption risks.

Establish a dedicated unit or person within each ministry to assist working groups in the management of corruption risks.

These behavioural informed strategies would increase capacities, opportunities, and motivations from working group members to carry out the most important steps from Decision 599/2018. The following Table 2.2 summarises the COM-B elements that these strategies expect to alter.

Table 2.2. COM-B elements to be altered by the behavioural strategies

|

Strategy |

COM-B element altered |

|---|---|

|

Redesign the risk registers to include intermediate indicators for intervention measures |

Capacity by more learning through feedback |

|

Opportunity to receive more feedback |

|

|

Motivation mediated by increased capacities |

|

|

Design a user guide for the adoption of corruption risk methodology in Decision 599/2018 |

Capacity by user guides with instructions |

|

Opportunity to learn from best practices |

|

|

Develop a web-based application to guide the corruption risks management |

Opportunity to decrease the effort of looking for several sources of integrity incidents |

|

Opportunity to learn from best practices in the repository |

|

|

Establish a dedicated unit or person within each ministry to assist working groups in the management of corruption risk |

Capacity to learn from advice |

|

Opportunity to ask for advice to more senior public officers |

2.2.1. Redesign the risk register to include the intermediate indicators for intervention measures

As argued in Chapter 1, the current corruption risk registry in Table 1.1 does not explicitly demand an action plan for the intervention measures. Without clear indicators, working group members cannot receive feedback on their efforts to control corruption. This is important for directing effort as it reduces the discrepancies between the current understanding and the actual performance (Hattie and Timperley, 2007[15]). When feedback is provided, it can inform decision makers on the nature of goals, their progress and the quality of that progress.

Going back to the COM-B model (Michie, van Stralen and West, 2011[13]), the inclusion of intervention measures may increase the chances for feedback, which in turn would increase subjects' psychological capacities to design better preventive measures. Because the lack of corruption is hard to measure, feedback could also be given as a measure of progress to the end goal. This means that feedback could come from the completion of activities, intermediate outputs and end results.

Regardless of final impact of preventive measures, which is usually beyond the control of the public official, the intermediate outcomes are direct results of the activities implemented. Outcome progress indicators could provide feedback on the implementation of measures. Better feedback could be provided if intervention measures are designed using a logical frame that connects activities, intermediate outcomes, and results. In this situation, short term indicators would increase the information on the intervention performance, allowing working group members to learn and increase their ability to design effective intervention measures that lead to the expected results.

Following the OECD (n.d.[16]) guidelines for drafting sectorial anticorruption strategies developed in the context for a project with Greece, this section proposes a new corruption risk registry that includes indicators for activities, intermediate outputs, and results. The inclusion of these indicators could guide working group members to elaborate a clear action plan for their control measures. Table 2.3 presents the proposed corruption risk registry. Unlike the current registry in Table 1.1, this includes three new columns: the intervention actions, the intervention outputs, and the results indicators. To produce adequate feedback, the columns need to detail the quantity of actions planned, the number of outputs that should be produced, and an observable result. They also need to specify the timeline for each indicator so that working group members can monitor their progress during the implementation. The “Deadline / Implementation duration” from the current registry has been removed as it is more important to monitor when results can be expected than to know for how long the strategy will be implemented.

Table 2.3. Proposed corruption risk registry for the Romanian central government

|

The field of activity in which the risk of corruption is manifested |

Risk description |

Cause |

Likelihood |

Impact |

Exposure |

Intervention measure description |

Implementation responsible |

Intervention actions indicators (including timeframe) |

Intervention outputs indicators (including timeframe) |

Results indicators (including timeframe) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Including three additional columns comes with its trade-offs. In practice, this increases the amount of time working group members need to spend on these tasks, which in turn, could reduce their motivation. Nevertheless, as is the case with promoting learning (Burgers et al., 2015[17]; Wisniewski, Zierer and Hattie, 2020[18]) and responsible gambling (Auer and Griffiths, 2015[19]), the use of informative feedback can increase individuals’ motivation to perform a costly behaviour.

2.2.2. Design a user guide for the adoption of the corruption risk methodology in Decision 599/2018

To increase the capabilities and opportunities for social learning among working group members, the Romanian government could design a user guide that includes instructions on how to use the corruption risk registry. The guide should include recommendations and examples but be concise enough to not decrease working group members motivations to use it. A general principle in behavioural science is that simpler strategies are better for promoting use than lengthier or more complex measures (The Behavioural Insights Team, 2014[20]). This guide could be designed with or without the proposed corruption risk registry from the previous section, but to increase its effectiveness it would be better if it includes the modified version as proposed above in Table 2.3.

Concerning the challenge highlighted in Chapter 1, the guide should include a precise definition of what “The field of activity in which the risk of corruption is manifested” means, to avoid confusions on how each central authority understands the context. There are at least three typologies that can be used to define the context: organisational structure, missional processes or missional objectives. Regardless of the definition used, the guide should be consistent so that all examples use the same definition. The use of a case study could help working group member resolve their doubts by looking at how other institutions have addressed their corruption risks.

The user’s guide should include, amongst others, a step-by-step manual on how to design intervention measures using a theory of change. A theory of change is a tool that proposes a causal link between an intervention and a specific change and details the analysis and assumptions that make that causal link reasonable (UNDAF, 2017[21]). This method can help working group members design strategies that follow an internal logic linking interventions with expected outcomes.

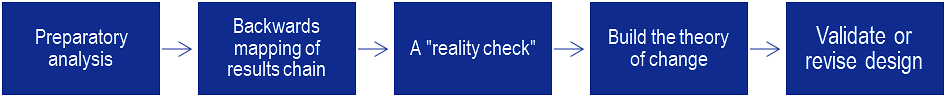

To develop a theory of change for an intervention measures, the user’s guide could include the five steps proposed by (Johnsøn, 2012[22]) laid out in Figure 2.1 to design new interventions or to evaluate the logic of existing interventions:

The first step to design a theory of change is to find out what works to reduce the identified corruption risk. This can be done through a literature review, through expert advice or support (within or outside the organisation as recommended below), or by consulting good practices from other private or public organisations. This analysis should consider the context and identify other actors, incentives and interests that may support or negatively affect the implementation of the measure.

Second, the pathway to create change should be mapped by the working group members using a result chain that links the intervention activities (i.e. training, staff rotation) to the desired change (the goal). The goal should be stated as specific as possible. A result chain is elaborated working backwards, starting from the desired impact (the goal) and then identifying first concrete intermediate outcomes and/or outputs (products) needed to achieve the goal and, only at the end, the activities required to achieve these outputs or intermediate outcomes. These intermediate outcomes, outputs (products) and activities can be mapped by the working group members in a brainstorming.

Third, working group members should assess the coherence and internal logic of the intervention measure by performing a reality check. The reality check consists in working through the result chain from the activities to the goal, while playing the devil’s advocate and challenging the underlying logic. This starts by formulating explicitly the causal pathway: “if this is implemented (activities), then this will happen (intermediate outcomes/products) and the goal will be achieved, because of the following reasons…”. Working group member should ask critical questions which could include, for example, asking if there are enough resources, if there is sufficient time available or asking if there might be internal or external factors that could negatively affect the causal logic.

Fourth, based on the previous steps, the working group members can build a theory of change that identifies explicitly the conditions for success and the underlying assumptions regarding the causal pathway. A distinction should be made from the conditions which the organisation can control and address and those that fall outside the sphere of influence of the organisation. Nonetheless, these external conditions should be monitored knowing they might affect the success of the intervention.

Finally, in the fifth step, after developing the intervention based on a theory of change, working group members should engage with various stakeholders to evaluate whether the intervention correctly identifies the necessary conditions for change. External commentators may provide valuable insights to strengthen the reasoning and could suggest additional activities to address conditions that could affect the success of the intervention.

Figure 2.1. Steps to develop a theory of change

The advantage of following these steps is that building a theory of change makes explicit the conditions and assumptions underlying the proposed intervention to mitigate the identified integrity risk and mitigates the risk of, at best, ineffective interventions or, worse, resulting unintended consequences. Building a theory of change also makes it more difficult for working group members to just jump straight into “easy solutions”, such as “training”. This had been identified as one of the challenges affecting the quality of the current corruption risk management (Chapter 1). Indeed, the pathway stating that “if an integrity training programme on whistleblowing is implemented, then people will start reporting corrupt activities which will reduce risks of tailored terms of references in procurement processes” makes it clearly difficult to find a logic (“because”) that would easily enable linking the activity (training) with the intermediate outcome (increased reporting and reduced risk of corruption in procurement). Changing the behaviour of public officials who tailor terms of references to favour specific companies are indeed unlikely to change because of a training.

2.2.3. Develop a web-based application to guide the management of corruption risks

Risk identification, likelihood and impact estimation as well as the design of control measures require substantial knowledge of formal and informal practices that may lead to corruption, a fair understanding of how public institutions work and information on the effectiveness of intervention measures in reducing corruption risk. Public managers typically do not have such expert knowledge and it would not be efficient trying to transform all public managers into anti-corruption experts. An IT tool could provide guidance and increase the opportunities for working group members to complete the corruption risk management steps and reduce the chances of defaulting to heuristics to simplify their work. As previously mentioned, these shortcuts could cause them to overlook important information and continue to use existing control measures that have no evidence of preventing corruption risks.

A web-based application could provide easy access for public managers to historical information on corruption incidents in both their own and similar institutions. This would reduce the time spent reviewing internal and external sources, deducing how such incidents are relevant to their organisations as well as estimating their likelihood of occurrence and their financial and reputational impact.

The tool could also include a repository of good practices in corruption prevention. The repository could display information on how control measures have been used, their implementation term, the challenges in their implementation and their effects on the institution. Such a tool would provide more opportunities for working members to access relevant information, which may increase their motivation to correctly adopt the corruption risk methodology and improve the quality of the risk management exercise.

The web-based app for Assisted Management of Corruption Risks (Managementul Asistat al Riscurilor de Corupţie, MARC in Romanian) introduced by the Romanian Ministry of Internal Affairs provides an example of how this tool could be developed. The implementation of the MARC began in 2014 by having senior public servants fill an integrity incident registry database to identify the most vulnerable areas of the ministry. After an area was flagged as vulnerable, a new intervention measure had to be designed, and the intervention was inspected by an officer in charge of implementing MARC. This process reduces the cognitive effort required to identify corruption risks from multiple sources. Consequently, working group members could focus their limited time to the most important risks and to the design of effective control measures.

To be effective, this application would need dedicated personnel to prefill the integrity incident registry and classify the incidents according to the field of activity in which they occurred. Senior staff with extensive knowledge of public organisations should prefill the information of contributing factors for each field of activity or vulnerable areas. This would contribute to flagging areas where there have been no previous integrity incidents but where there are risks due to the certain contributing factors to corruption risk.

Given that all public institutions share the same support activities, such as procurement, human resources, IT, to give a few examples, a centralised task could be established to identify corruption risks relevant to such cross-cutting aspects that are relevant to virtually every public entity. This would allow the working group members from each organisation to focus more on identifying the risks in their specific mission fields of activities. During the OECD fact-finding mission, public officials from the National Integrity Agency (Autoritatea Națională de Integritate, ANI) proposed that each authority or institution with responsibilities for such cross-cutting tasks could provide a list of predefined risks, based on their respective legal competencies (e.g. the ANI for conflict of interest and incompatibilities etc.). In a next step, these risks could be introduced as an annex within the methodological framework to facilitate the identification of the predefined risks for other authorities and institutions.

2.2.4. Establish a dedicated unit or person within each ministry or at sector level to assist working groups in corruption risk management

To support the working groups in corruption risk management, each central public organisation could establish a dedicated person or unit. Alternatively, a dedicated unit could also provide guidance at sector level, for example this could make sense for the health or education sectors. As mentioned in the previous section, while working group members are experts in their respective departments, they may not have the necessary expertise regarding risk management or corruption. Therefore, a dedicated unit could provide guidance and support in risk identification, likelihood and impact assessment and the design of intervention measures. Dedicated persons or units could also play a crucial role in providing expert feedback on the risk assessment process. Their knowledge and experience could help identify potential areas of corruption. This person or unit would provide support and oversight activities on the use of the corruption risk management methodology and in the promotion of integrity measures (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. The three lines model of the Institute of Internal Auditors

The three lines model is a framework that outlines roles of organisation’s areas to assure an effective management of risk. Different parts and levels of an organisation play different roles in risk management, and their interaction determines how effective the organisation is in dealing with risk. The roles of each line are as following:

The first line includes the operational activities of an organisation, such as risk management, compliance and internal controls that are performed by front-line employees and managers.

The second line involves activities that are conducted by specialists to provide complementary expertise, support, monitoring and challenge to those with first line roles.

The third line, the internal audit function, includes independent and objective assurance to provide an objective assessment of an organisation's operations and controls. The third line of defence serves to provide additional assurance to stakeholders and to help ensure the overall integrity and accountability of an organisation.

During the fact-finding mission in Romania, the OECD identified two ministries that have implemented dedicated units to assist their working groups in corruption risk management. The first example is the Anti-Fraud, Integrity and Inspection Directorate (Direcția Antifraudă, Integritate și Inspecție) from the Ministry of Energy. This unit is a specialised division in risk management counselling that merged the operational and corruption risk into a single division. The second example is the General Anticorruption Directorate (Direcția Generală Anticorupție) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The head of this permanent unit is the integrity plan coordinator and the leader of the working group. This unit is also in charge of supervising the use of MARC for the ministry and of assisting working group members in case they have any doubts when using the IT tool.

Both cases exhibited also the most mature corruption risk management practices among the entities interviewed by the OECD. The experiences from these two dedicated units could serve as a guide to standardise the functions of integrity units and promote their establishment across the public sector. This would allow the specialised public officials to better understand all the external and internal risk sources to the organisation or the sector. In addition, if the IT tool were to be implemented, this dedicated person or unit could provide support in pre-filling the integrity incidents, provide examples of best practices in intervention measure for its sector and assist public officials with any requirements regarding its use. The example of the Integrity Management Units in Brazil´s federal public administration or the Peruvian Offices of Institutional Integrity are interesting practices that could be adapted to the Romanian context (OECD, 2022[24]; OECD, 2021[25]; OECD, 2019[26]).

As recommended in another OECD report (OECD, 2023[2]) and since the establishment of dedicated integrity units requires resources, Romania could also consider strengthening the existing ethics counsellors from this perspective. These ethics counsellors, required by Government Emergency Ordinance 57/2019, are appointed by the heads of public authorities and institutions. Through trainings on Decision 599/2018 aimed at developing their capacities in leading the corruption risk management process within their entities, they could in the future contribute to the role of internal drivers mentioned above. However, currently, these ethics counsellors are too weak, as they lack resources, have other functions in addition to the ethics counselling, are too often changed to build expertise and becoming known internally and lack decision-making powers (OECD, 2023[2]).

Not at least, the Government of Romania could consider designing and implementing a communication strategy to support the adoption and implementation of Decision 599/2018 as well as the any of the measures recommended above. Annex C provides some guidance on such a communication strategy (Annex C).