The purpose of a HSPA Framework is to provide a shared vision of the main elements of health systems that require focused policy attention. By formally endorsing additional dimensions of performance – such as people‑centredness and resilience – that have in recent years moved to the fore of policy attention and are critical for health policy developments, a renewed HSPA Framework allows more comprehensive assessment of performance and thereby guides future analytical and indicator work for the OECD. This chapter describes the renewed Framework, its components, and how these relate to each other.

Rethinking Health System Performance Assessment

2. General structure of the renewed Health System Performance Assessment Framework

2.1. General structure of the renewed HSPA Framework

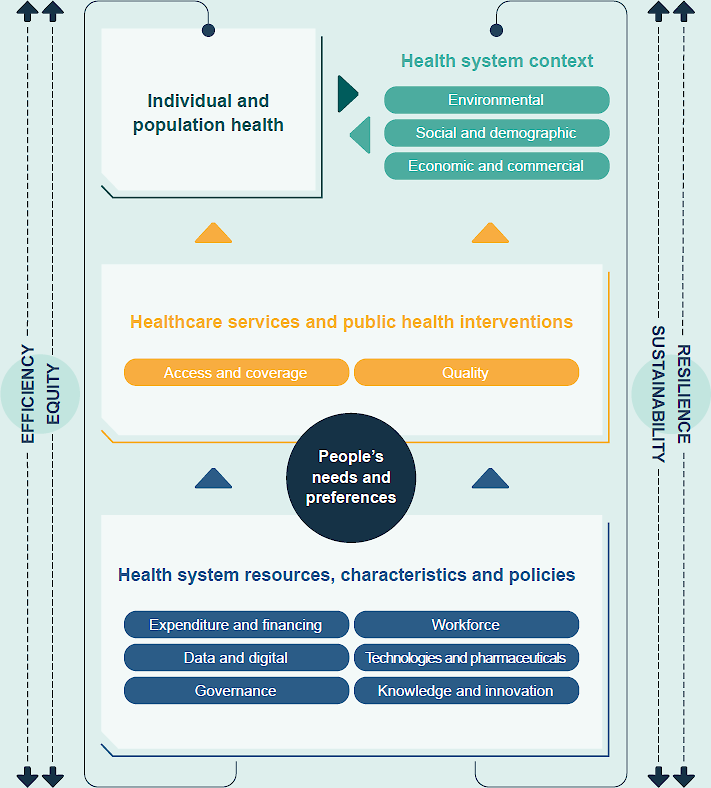

Figure 2.1 shows the overarching Framework. The “classic trio” that is at the basis of most HSPA frameworks – input, process, and outcomes – is visible in the Framework (Donabedian, 2005[10]). The figure shows that resources and policy are fed into health services and interventions, that, in turn, produce outcomes.

Figure 2.1. Renewed OECD Health System Performance Assessment Framework

2.2. Socio-economic, demographic, and environmental conditions

The socio-economic, demographic, and environmental context refers to the broader conditions that influence and interact with the health system. The OECD HSPA Framework focuses on the health system and does not serve as a conceptual model for determinants of health. However, as the Dahlgren and Whitehead model effectively illustrates (see Annex A), this category includes a wide range of determinants whose combined impact exceeds that of the health system as a whole (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 2021[11]).

The overall context plays a significant role in shaping the functions of all health systems, either by facilitating or restricting their performance. For instance, discussions on access or financing are bound by the macroeconomic situation and fiscal space within which they operate. Similarly, health workforce policies may differ depending on the age structure of a given country, with more ageing societies requiring greater proportion of social care workers. In summary, this dimension intends to comprehend how these external influences and factors impact both people’s health and the performance of health systems, while also recognising that health system actions (and in turn peoples’ health) significantly affect the environmental, economic, commercial, and social contexts. The Framework illustrates that this entire relationship is circular rather than linear.

2.3. Individual and population health

The outcomes of health systems represent a crucial component of health system performance assessment frameworks. It refers to the consequences of a health system’s activities, policies, and interventions on the health and well-being of the population. Practically all existing HSPA frameworks identify health, either population health, individual health, or health improvement as an essential goal of health systems (Papanicolas et al., 2022[12]; Perić, Hofmarcher and Simon, 2018[13]).

2.4. Putting people’s needs and preferences at the centre of health system resources and interventions

The proposed Framework places people’s health needs and preferences at the core of health system, reflecting the directions from the 2017 OECD meeting of Health Ministers to make health system more people‑centred (OECD, 2017[14]). As such, people‑centredness is regarded both as an objective of health systems, as well as being instrumental to achieving other policy objectives. Incorporating the elements of the People‑Centred Health Systems Framework, people‑centredness can be expressed through its five sub-domains: voice, choice, co-production, respectfulness and integration.

The section on health systems resources and characteristics covers the “structural” elements of health systems, i.e. the inputs necessary to enable the health system to function and the context in which it operates. It includes the following six pillars:

expenditure and financing

workforce

data and digital

technologies and pharmaceuticals

governance

knowledge and innovation.

Rather than introducing new topics, the renewed Framework presents those that are already widely covered by ongoing OECD work, such as data reported in Health at a Glance (OECD, n.d.[15]) and the data collected in the Health Systems Characteristics Survey (OECD, n.d.[16]) (see next chapter).

Healthcare services and public health interventions: this part includes all activities that fall under healthcare, such as curative care, long-term care mental health care, or palliative care, etc. but also prevention and health promotion, such as screening, vaccination or public health campaigns. Maintaining the essence of the 2015 HSPA Framework, “access and coverage” and “quality” are important system objectives as well as indicator domains. They both collectively determine the effectiveness and fairness of healthcare delivery. “Access and coverage” ensure that individuals can readily obtain the healthcare services they need, regardless of their geographical location, financial status, or social/cultural background, promoting equal opportunities for health. “Quality”, on the other hand, focuses on the standards and effectiveness of healthcare services, safeguarding patient safety and ensuring that care is evidence‑based and meets established and validated practices. Monitoring and optimising these dimensions are crucial for addressing healthcare disparities and achieving health systems goals.

2.5. Four cross-cutting dimensions traverse the Framework

The renewed Framework now includes four “cross-cutting” dimensions of health system performance, namely efficiency and equity on one side, and sustainability and resilience on the other. The reason that these are cross cutting is that they do not belong to one particular block in the Framework but relate to them all.

For example, equity refers to how well resources are allocated to serve different socio‑economic groups in the population, how quality of care or access to care varies across these groups, and finally, how health varies across these groups. An indicator for quality of care, such as the rate of hospital admissions for diabetes could also be an equity indicator when broken down by socio-economic groups.

Measuring efficiency in health systems is concerned with a comparison of inputs with outcomes of the healthcare system to assess the degree to which goals are achieved while minimising resource usage. Improving the efficiency of health systems is a key policy objective to reconcile growing demands for healthcare with constrained budgets.

Resilience involves ensuring that health system performance continues under extreme stresses and across the domains that determine its performance. This relates to factors within health systems (including capacity, physical resources, workforce and information systems) and beyond them (including a view of the socio‑economic determinants of health).

Finally, the Framework also includes the sustainability dimension. The most common usage of sustainability in health system performance refers to the fiscal sustainability aspect, i.e. the ability of a government to maintain public finances at a credible and serviceable position over the long term (OECD, 2015[17]). However, sustainability also refers to a broader idea of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland Commission, 1987[18]), a concept that has underpinned the discussions of environmental sustainability and that has large relevance for health policy particularly in the context of climate change. Both interpretations are relevant cross-cutting dimensions in assessing health system performance.

2.6. Relationships across dimensions

The concepts used in the Framework are not necessarily mutually exclusive, therefore they may overlap. Some relations between concepts are acknowledged in the Framework. For example, although different terminology is used, Donabedian’s model of structure, process, and outcomes (Donabedian, 2005[10]) remains visible in the Framework through the relationships between health system resources, characteristics, and policy (structure); healthcare services and public health interventions (process); and individual and population health (outcomes).

Yet, the Framework remains high-level. It shows the main elements in relation to each other at a higher level and is not intended to detail all possible conceptual relationships. The high-level approach makes it suitable for application to a range of countries with very different geographical sizes, economies and health systems. The various impacts of the health system are also interrelated: individual and public health can affect people’s wealth and vice versa; health inequalities can foster other socio‑economic inequalities; health systems have an impact on the environment, for example through emissions and waste, while the environment also affects people’s health.

Endorsing a high-level Framework allows for the possibility to “zoom in”, unpack and elaborate dimensions of the Framework in more detail, for example via sub-dimensions, complemented by a series of accompanying measures and linked indicator portfolios at working level, that can be used to facilitate cross-country analysis and comparisons. In short, this high-level Framework will set a vision; more detailed measures, indicators, and programmes of work – current and future – will facilitate work to realise that vision. Chapter 3 will elaborate on the different concepts and components of the Framework and populate them with indicators, existing or to be envisaged.