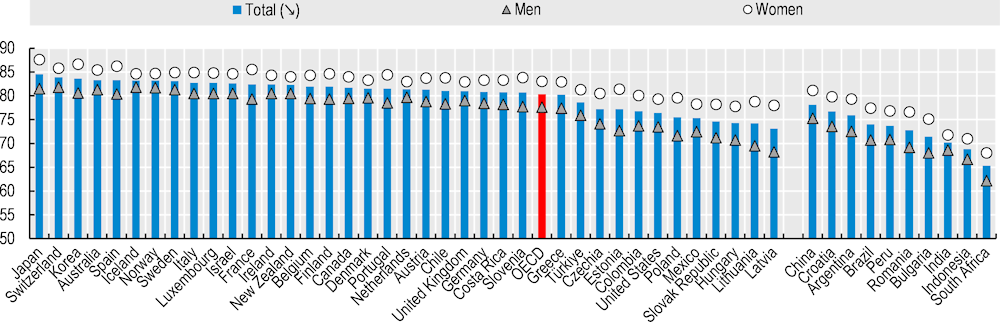

In 2021, life expectancy at birth stood at 80.3 years on average across OECD countries (Figure 7.1). Life expectancy at birth exceeds 80 years in more than two‑thirds of OECD countries, with Japan, Korea and Switzerland at the top of the ranking. The United States, Latin America and several Central and Eastern European countries have a life expectancy between 75 and 80 years. Among OECD countries, life expectancy is lowest in Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic, at slightly below 75 years. In all partner countries, life expectancy remains below the OECD average, notably in South Africa (65.3), Indonesia (68.8) and India (70.2).

Life expectancy at birth varies by gender, at 83.0 years for women compared with 77.6 years for men in 2021 on average across OECD countries (Figure 7.1). The gap reaches an average of 5.4 years. These gender differences in life expectancy are partly due to greater exposure to risk factors among men, in particular greater tobacco consumption, excessive alcohol consumption and less healthy diets. Men are also more likely to die from violent deaths, such as suicide and accidents. Gender differences in life expectancy are particularly marked in Central and Eastern European countries, in particular Latvia, Lithuania and Poland with gaps of eight or more years. Gender gaps are relatively narrow in Iceland, and in Norway, at three years or less.

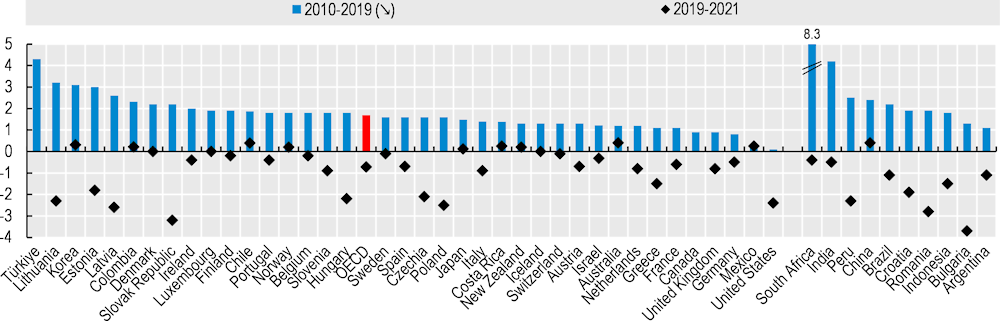

COVID‑19 has had a major impact on life expectancy due to the exceptionally high number of deaths this pandemic has caused. Prior to the pandemic, life expectancy increased in all OECD and partner countries between 2010 and 2019, with an average increase of 1.7 years across OECD countries (Figure 7.2). However, much of these gains were lost with the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2021, life expectancy decreased by 0.7 years on average across OECD countries. Reductions were highest in Central and Eastern European countries and the United States. Seven OECD countries lost as many or more years of life expectancy during the first two years of COVID‑19 than they had gained in the past decade (Czechia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, the Slovak Republic and the United States). This was also the case in partner countries Argentina, Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania. Nevertheless, life expectancy between 2019 and 2021 did not decrease in all countries, but if gains were made, they were small.

Even before COVID‑19, gains in life expectancy had been slowing down markedly in a number of OECD countries over the last decade. This slowdown was most apparent in the United States, France, the Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom (Figure 7.2). Longevity gains were slower for women than men in almost all OECD countries. The causes of this slowdown in life expectancy gains over time are multi-faceted. A principal cause is slowing improvements in treatment and prevention of heart disease and stroke. Rising levels of obesity and diabetes, as well as population ageing, have made it difficult for countries to maintain previous progress in reducing the number of deaths from such circulatory diseases.

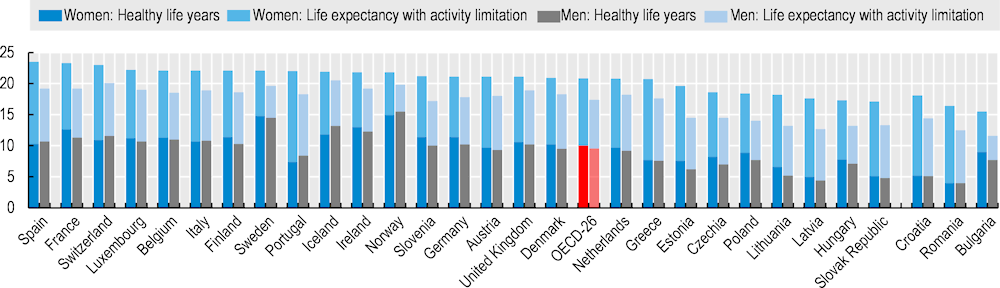

On average across OECD countries in 2021, people at age 65 could expect to live a further 19.5 years. Life expectancy at age 65 is around 3.3 years higher for women than for men. Among OECD countries, life expectancy at age 65 in 2021 was highest for women in Spain (23.5 years) and for men in Iceland (20.5 years). It was lowest for women in the Slovak Republic (17.1 years) and for men in Latvia (12.7 years) (Figure 7.3).

The number of healthy life years at age 65 varies substantially across OECD countries. On average, the number of healthy life years at age 65 was 10 years for women and 9.6 for men in 2021 – a noticeably smaller difference between men and women than that for general life expectancy at age 65. Healthy life expectancy at age 65 was close to or above 14 years for both men and women in Norway and Sweden; for men, this was nearly 2 years above the next best performing countries (Iceland and Ireland). Healthy life expectancy at 65 was around 5 years or less for both men and women in the Slovak Republic and Latvia. In these countries, women spend nearly three‑quarters of their additional life years in poor health, compared to one‑third or less in Norway and Sweden.