This chapter provides an overview of key findings and policy considerations outlined in the country study to strengthen FDI and SME linkages in Czechia. Specifically, it presents the main challenges and opportunities for foreign direct investment (FDI) and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and examines their role in supporting productivity and innovation. Based on an assessment of Czechia’s regulatory and policy framework, the chapter also derives recommendations for policy reform to strengthen the spillover potential of FDI and the productive capacities of Czech SMEs, including in the regions of South Moravia and Ústí nad Labem.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Czechia

1. Overview and key policy considerations

Copy link to 1. Overview and key policy considerationsAbstract

1.1. The enabling conditions for FDI and SME linkages in Czechia

Copy link to 1.1. The enabling conditions for FDI and SME linkages in CzechiaBenefiting from its strategic geographical location, a strong industrial base, and competitive labour costs, Czechia has achieved robust economic growth, supporting its successful convergence towards OECD and EU average incomes. Despite a strong economic record, Czechia’s labour productivity, measured as output per person employed, still lags behind the OECD and EU averages, pointing towards potential structural issues that may impede productivity-enhancing capital reallocation. The stalling of labour productivity levels in key segments of the economy, including in the FDI-intensive manufacturing and finance sectors, also raises the question of whether domestic firms are able to benefit from the knowledge and technology that foreign firms bring in these sectors. Considerable and widening disparities in GDP per capita and labour productivity across subnational regions also exist.

Although the economy is predominantly services-oriented, the importance of the manufacturing sector in terms of value added, employment and exports is higher than in neighbouring CEE economies – mainly driven by the automotive sector and other high-technology manufacturing industries. The Czech economy holds a comparative advantage in the production of several low- and high-technology goods (e.g. fabricated metals, plastics, motor vehicle components). Similarly, a technological advantage – in terms of number of patents submitted for specific technology fields – is observed in nanotechnologies, pharmaceuticals and environmental management technologies (including for green transportation). Czechia can capitalise on existing advantages in the production and export of these products to further develop key industries by attracting investment and strengthening the capacities of domestic firms, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Czechia has seen rising exports as a share of GDP over the past decade, surpassing many advanced European economies and the OECD average. The Czech economy has been specialising in assembling processed goods using intermediate inputs from abroad. This may have important implications for FDI and SME linkages since it indicates that MNEs based in Czechia import a large proportion of intermediate inputs, limiting procurement from local suppliers.

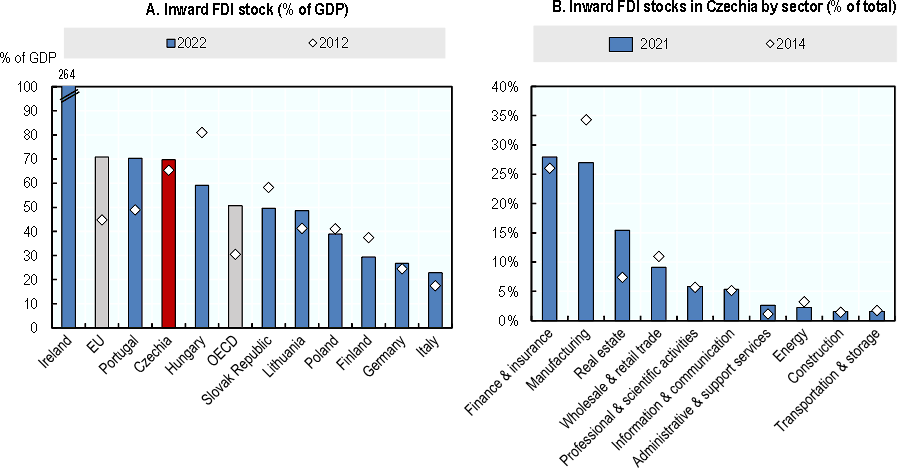

Czechia has experienced a significant influx of foreign direct investment (FDI) since the late 1990s. This has been pivotal in integrating the Czech economy into GVCs and bolstering international trade. The COVID-19 pandemic and the geopolitical upheavals following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine impacted global trade and investment. However, FDI inflows into Czechia remained rather resilient, with only a moderate 7% decline between 2019 and 2020, followed by a robust recovery in subsequent years. Over the past decade, sectoral patterns of FDI have shifted, moving away from traditional manufacturing towards low-technology services (e.g. finance and insurance activities, real estate) (Figure 1.1). The finance and real estate sectors have seen the largest relative increase in total FDI stock, while the relative contribution of manufacturing, particularly the automotive industry, has declined. Concurrently, non-automotive manufacturing industries have seen an uptick in their share of FDI stocks, indicating the potential development of FDI-SME ecosystems across a broader and more diversified range of industrial sectors with benefits to aggregate growth and productivity.

Figure 1.1. Foreign direct investment trends in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 1.1. Foreign direct investment trends in Czechia

Source: OECD (2023), International Direct Investment Statistics, http://www.oecd.org/investment/statistics.htm; and Czech National Bank (2023), FDI positions in the Czech Republic, https://www.cnb.cz/cs/statistika/

Although sectors that account for large FDI stocks are on average more productive, they account for a small share of business R&D expenditure. Only 4% of greenfield investments have involved R&D activities, a higher share than neighbouring CEE economies but significantly below leading European countries. Foreign-owned firms in Czechia are twice as productive as domestic firms, particularly in low-technology services (e.g. finance and insurance, real estate). This productivity gap highlights the potential for FDI spillovers, as foreign firms, often larger and more export-oriented, possess superior access to finance, skills, and innovation assets. However, in some sectors, such as manufacturing, the productivity differences between foreign and domestic firms are narrower, suggesting a potential parity in operations and opportunities for knowledge exchange within these industries.

Czechia’s economy is dominated by low productivity micro firms that make up 96% of the business population, accompanied by limited business dynamism as illustrated by the low enterprise birth and death rates. These micro firms, contribute disproportionately little to value added and turnover relative to their employment share. The notable absence of medium-sized enterprises indicates systemic challenges in scaling up operations and fostering knowledge and technology transfers to smaller businesses, particularly in sectors that are crucial to the domestic economy and have attracted significant FDI levels. Overall, SMEs have an important role in the lower technology manufacturing sector, accounting for 46% of employment and 45% of value added (e.g. manufacture of metals, machinery and equipment, leather and textile products).

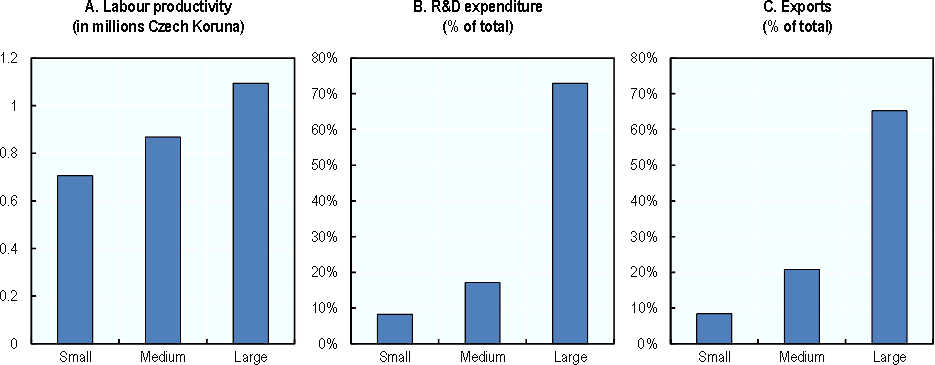

As in other OECD economies, SMEs in Czechia are lagging behind larger firms in terms of direct and indirect exporting, reflecting their limited capabilities to expand operations abroad and serve as suppliers of foreign firms (Figure 1.2). SMEs are also less engaged in FDI-intensive sectors (e.g. automotive, electronics and fabricated metals) that could present opportunities for supplier linkages with foreign multinationals. Czech SMEs report facing important barriers to innovate (e.g. high costs, lack of qualified employees, lack of internal finance) but have significantly improved their performance in introducing product, process and organisational innovations and in collaborating with other innovative firms over the past decade. They are, however, responsible for a small share of business R&D expenditures, signalling weak business-science linkages and limited opportunities for SMEs’ involvement in inter-firm collaborations in knowledge-intensive activities.

Czech SMEs are on par with SMEs in the EU in terms of digital transformation. Their performance is higher in the use of certain digital technologies, including cloud services, the Internet of Things (IoT), 3-D printing and e-commerce. The digital intensity gap between large and small firms is more pronounced in certain supplier and customer management technologies (e.g. CRM and ERP software), which are often a prerequisite for SMEs to form buyer-supplier linkages with large multinationals and benefit from spillovers in GVCs. While Czechia performs well in terms of basic digital skills and has a relatively high proportion of ICT graduates, 76% of Czech enterprises report difficulties in recruiting ICT specialists. Overall, SMEs prioritise investments in the skills development of their employees and outperform their EU peers in the provision of staff training. Access to finance is, however, constrained, with declining new SME business lending and late payments impacting the supplier relationships of smaller firms. Alternative sources of finance are in limited use by Czech SMEs, posing challenges to their scaling up and to the funding of innovative and riskier ventures.

Figure 1.2. Performance of small and medium-sized enterprises in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 1.2. Performance of small and medium-sized enterprises in Czechia

Note: Data for labour productivity and R&D expenditure are from 2020 while for exports from 2021.

Source: OECD (2022[1]), Trade by Enterprise Characteristics database; OECD (2022), Structural Demographics and Business Statistics (SDBS); and OECD (2021) Research and Development Statistics Database

1.2. FDI spillovers at play for Czech SMEs

Copy link to 1.2. FDI spillovers at play for Czech SMEsFor FDI-SME spillovers to occur, domestic SMEs should be exposed to activities of foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) either directly or indirectly. When SMEs are exposed to MNE activities they form linkages. Strengthening these linkages enhances productivity spillovers through the diffusion of knowledge, technology and skills to domestic firms, and by improving the innovative and scale-up capabilities of SMEs. Core channels of FDI-SME diffusion include value chain relationships, strategic partnerships, labour mobility, competition and imitation effects.

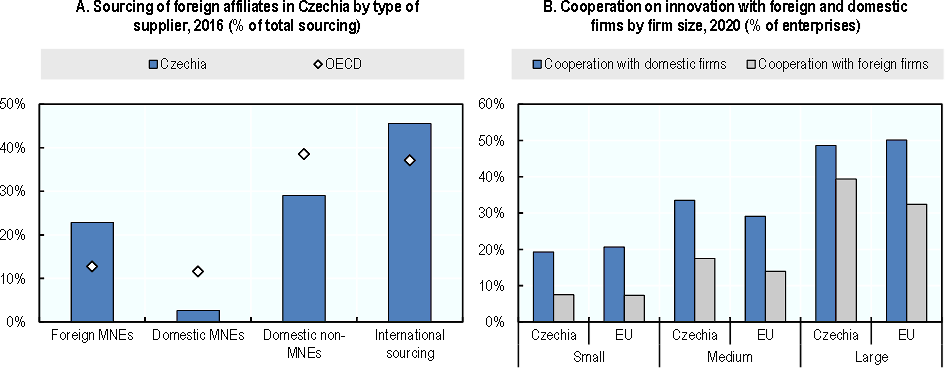

Foreign MNEs can obtain intermediate inputs from local suppliers (i.e. supplier linkages) or by importing from abroad. Opting to source inputs locally creates opportunities for growth for domestic firms, in particular SMEs. In Czechia, foreign affiliates import almost half of their intermediate inputs and source significantly less inputs locally compared to most OECD economies (Figure 1.3). This trend is observed across other small EU countries, including Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies, while foreign MNEs operating in larger economies like Germany and Italy tend to rely more on local suppliers due to the size of their domestic markets. Among foreign affiliates’ local suppliers, domestic-owned firms are responsible for almost one third of the inputs sourced. Although the majority of them are non-multinational firms – a category that likely includes most Czech SMEs –, their contribution to foreign affiliates’ sourcing structure is lower than that of domestic-owned firms in the OECD area, which are on average responsible for 50% of the sourced inputs. In contrast, other foreign affiliates operating in Czechia are more important sources of intermediate inputs (23% of total sourcing vs 13% at the OECD), suggesting some clustering of foreign affiliates in Czechia, which tend to buy from and supply each other.

Similarly, foreign affiliates’ output is mostly exported or sold to other foreign affiliates operating in the Czech market, indicating a lower potential for FDI-SME spillovers through buyer linkages. Such linkages are often a source of productivity spillovers because they allow domestic firms to access new, higher-quality or cheaper intermediate inputs. Many MNEs also offer training to their customers on the use of their products and provide information on international quality standards.

Beyond supplier-buyer linkages, foreign MNEs and domestic SMEs can establish strategic partnerships around the development of joint R&D and innovation projects, which can create opportunities for technology transfer, especially in high-technology and knowledge intensive industries. In Czechia, foreign MNEs and domestic SMEs establish cooperation through strategic partnerships in R&D and innovation particularly in high-technology and knowledge-intensive industries. Overall engagement in cooperation among Czech firms is moderate, with smaller enterprises lagging behind larger ones. Strategic partnerships particularly with foreign firms are less common among smaller Czech firms, indicating potential challenges in fostering linkages with foreign firms (Figure 1.3). Although Czech firms engage in technology licensing agreements at levels comparable to or higher than many comparator economies, foreign firms in Czechia appear to be less involved in such partnerships compared to their counterparts elsewhere.

Labour mobility can serve as a channel for knowledge spillovers, particularly through the movement of MNE workers to local SMEs. In Czechia, however, job-to-job mobility is lower than in many peer economies, especially in science and technology related sectors. While job mobility within the local labour market is limited, conditions for mobility of highly skilled foreign workers are relatively restrictive, with less favourable permit duration and labour market mobility conditions compared to neighbouring countries. Moreover, wages in foreign firms are significantly higher than in domestic firms especially in the services industry (e.g. information and communication, finance, and professional services), discouraging labour mobility and associated skills spillovers to domestic firms. The potential for FDI-SME spillovers through labour mobility also depends on FDI’s skills intensity, as well as training and learning opportunities that SMEs have in the domestic economy, amongst other factors. Czechia is among the few countries, where foreign firms do not outperform their domestic counterparts in terms of training opportunities. This could be linked to the concentration of FDI in sectors creating few jobs such as the capital-intensive real estate and finance sectors as well as in low-value added manufacturing linked to assembly and processing, which may not always require highly specialised and technology-intensive skills.

FDI-SME spillovers may also materialise through market interaction mechanisms driven by competition and imitation effects. Competition effects arise when MNEs enter the market, influencing domestic companies operating in the same sector or value chain segment, even if not geographically located in the same region. Conversely, imitation effects occur at a more local level when domestic firms emulate the practices of foreign MNEs, leading to enhancements in their productive and innovative capacities. In Czechia, cooperation with competitors on innovation is relatively common, suggesting potential for FDI-SME spillovers through tacit learning. However, same sector cooperation on innovation, particularly with foreign firms, is notably lower compared to other peer economies. A considerable share of SMEs in Czechia perceive competition as a barrier to innovate. This perception may reflect challenges in keeping up with new and potentially higher quality standards set by competitors, potentially resulting in fewer knowledge spillovers from foreign companies through imitation effects.

Figure 1.3. Supplier linkages and inter-firm cooperation on innovation

Copy link to Figure 1.3. Supplier linkages and inter-firm cooperation on innovation

Source: OECD (2019), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database; and Eurostat (2020), Community Innovation Survey 2020

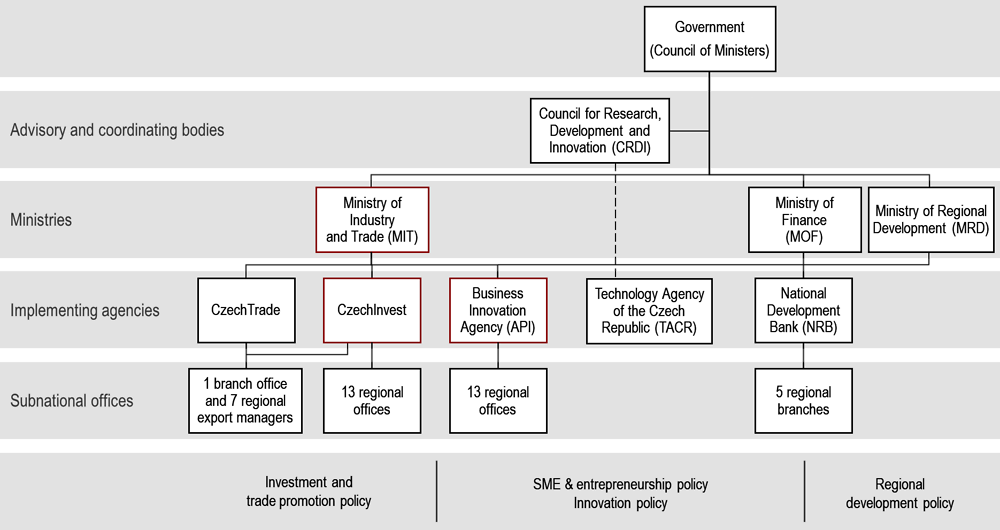

1.3. The institutional and governance framework for investment and SME policy

Copy link to 1.3. The institutional and governance framework for investment and SME policyThe governance framework for FDI-SME policy in Czechia is relatively integrated, yet it reveals the complexity inherent in a system where responsibilities are dispersed across numerous ministries. This structure ensures that multiple policy areas are taken into account, but may also lead to fragmentation. The institutions involved are the Ministry of Industry and Trade (investment promotion and facilitation through CzechInvest, SME and entrepreneurship policy which is implemented on the administrative level through the Business Innovation Agency); the Ministry of Finance (SME and entrepreneurship policy and regional development policy through the National Development Bank); the Ministry of Regional Development (regional development policy including managing EU funds and establishing subnational business support as the main mandate). Also, the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TACR) under the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) aims to foster the innovation capacity of Czech enterprises by financing R&D activities and facilitating networking effects (Figure 1.4).

In Czechia, the promotion of innovation and regional development is managed by a range of agencies, reflecting a common pattern seen in OECD countries. Responsibilities for innovation promotion are shared primarily between the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the recently established Ministry for Research and Innovation as they both have mandates in innovation policy, while the Council for Research, Development and Innovation works an advisory body to the Government. The Ministry of Regional Development outlines the regional development strategy.

The Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT) plays a central role. It bears the primary responsibility for investment, SME, and entrepreneurship policy, alongside its remit in energy, industrial, and trade policy. Hence, this ministry, is responsible for policies related to FDI-SME linkages, distributing responsibilities across several departments. While various departments within the MIT often collaborate, particularly in policies related to FDI-SME linkages, this cooperation typically relies on informal channels, highlighting a potential area for more structured and formalised coordination mechanisms.

The observed differences between the implementation of national policies at the local level suggest an opportunity for enhancing cooperation among ministries, national implementing agencies, their regional branches, and regional innovation centres (which are typically established by regional governments and have no direct link to national ministries). This enhancement could facilitate better alignment between national objectives and local actions, ensuring a more harmonious policy execution process and ensure the connection between national, regional, and local delivery of FDI, SME and innovation services. The empowering of regional innovation centers, one-stop-shops, and business consultation centres can be a step in the right direction. To enhance the effectiveness of this collaboration, greater tailoring of national policies at the subnational level should be combined with due coordination among national agencies operating locally and regional innovation agencies through regular meetings and consultations on an ad hoc basis.

Figure 1.4. The institutional environment for FDI and SME linkages in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 1.4. The institutional environment for FDI and SME linkages in Czechia

Note: The main institutions acting upon FDI and SME linkages are designated in red. All the other institutions provide a complementary contribution to FDI and SME linkages.

Source: OECD elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023).

In Czechia, several strategic documents have been adopted in recent years to articulate priorities related to investment and SME policy. National strategies and action plans can be important instruments for policy coordination as they are crosscutting in nature, and often require a whole-of-government approach to ensure their effective implementation. The number of different strategic documents in Czechia heightens the risk of making policy coordination more complex. These national strategies collectively address a wide range of areas including skills development, digital transformation, research and development, international market access, and the low-carbon transition. They are implemented through a collaboration of government bodies, with a significant role played by the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) and the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

In terms of policy development and evaluation, there is a notable opportunity to implement comprehensive evaluation frameworks to gauge policy impacts effectively. More than half of FDI-SME policy initiatives have integrated monitoring and evaluation (M&E) criteria, and Czechia outperforms the OECD average in terms of Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) implementation. There is still, however, room for enhancing the use of M&E in the policymaking process.

The current governance structure also shows gaps in involving a broader spectrum of stakeholders, including SMEs and local communities, in the policymaking process. This suggests an avenue for fostering richer and more varied inputs into policy formulation and evaluation, as well as the necessity to establish robust feedback mechanisms for building more responsive governance structures. These mechanisms can serve as valuable tools for ongoing policy refinement, ensuring that policies remain relevant and effective in achieving their intended outcomes.

One of the notable attributes of the Czech institutional framework is its ability to balance comprehensive policy development with a nuanced understanding of the specific needs of SMEs and FDI. The framework’s emphasis on coordination across various policy areas and government levels ensures that policies are not developed in isolation, but rather in a manner that reflects the interconnected nature of economic growth, innovation, and regional development. This approach, coupled with the MIT’s extensive involvement in a wide range of policy areas, demonstrates the Czech government's commitment on strenghthening SMEs and their innovative capacity and, to lesser extent, enhancing the impact of FDI on the domestic economy. The utilisation of various departments within the MIT to address different facets of the SME and FDI ecosystem showcases the government’s understanding of the intricate linkages between different economic sectors and their role in fostering a robust SME sector and attracting productivity-enhancing FDI. However, it is imperative to continually evolve and adapt the institutional framework. Strengthening formal coordination channels, without compromising the existing flexibility and adaptability which are critical in a dynamic economic landscape, could serve as a valuable enhancement to the Czech government’s policy execution, ensuring that the strategic objectives are harmoniously integrated across all departments. Enhancing formal collaboration, alongside the strategic focus on coherent policy development and implementation, could stand out as a key strength of the Czech institutional framework in fostering a conducive environment for SMEs and maximizing the benefits of FDI.

Box 1.1. Policy recommendations on the institutional and governance framework

Copy link to Box 1.1. Policy recommendations on the institutional and governance frameworkStrengthen inter-ministerial and inter-agency coordination through formal bodies and consolidation of responsibilities to improve efficiency in partnership with regional, publicly-funded organizations specializing in innovation services for SMEs.

Define clear, specialised functions for each agency to avoid overlap and focus on specific FDI-SME policy areas. Establish distinct mandates for each agency, ensuring they focus on specific areas like start-up support or SME financing, to avoid functional redundancy.

Create frameworks for better alignment of national policies with regional and local priorities. Greater tailoring of national policies at the subnational level should be combined with coordination among national agencies operating at local level and regional innovation agencies, to avoid an inconsistent quality of support or the provision of overlapping services in regions and places.

Implement a framework for regular impact evaluations to assess the effectiveness of FDI-SME policies, using both quantitative and qualitative metrics.

Facilitate regular, structured dialogues with a diverse range of stakeholders inside and outside national government.

1.4. The policy mix for strengthening FDI spillovers on Czech SMEs

Copy link to 1.4. The policy mix for strengthening FDI spillovers on Czech SMEsPublic policy plays a pivotal role in enhancing the performance and quality of FDI-SME ecosystems. An integrated approach, combining policy measures in investment, SME development, innovation, and regional development with a supportive regulatory framework, can increase policy effectiveness. Such integration might strengthen the attraction of FDI that enhances productivity and facilitates spillovers to local SMEs. The challenge lies in ensuring that the policy mix is well-aligned with the country's economic structure, policy priorities, and geographical specifics.

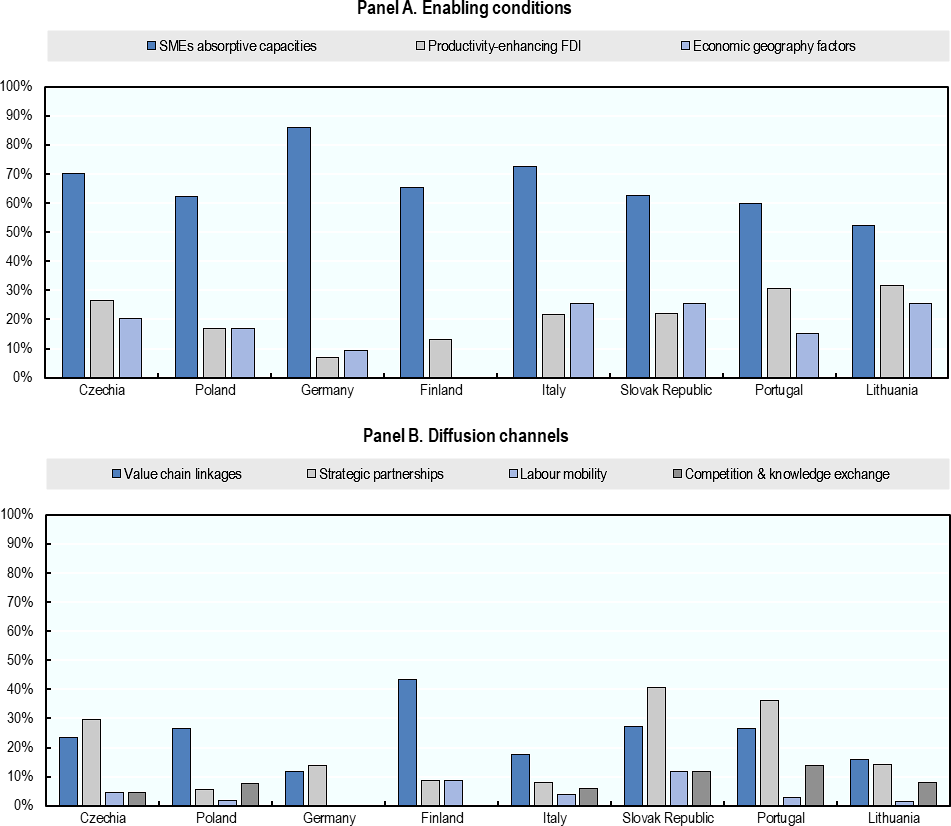

Czechia's policy mix for strengthening the synergy between FDI and SMEs focuses more on enhancing domestic SMEs' capacities than on creating new pathways for FDI impact. Czechia has many policies focused on supporting domestic SMEs, compared to a smaller number of policies aimed to assist foreign companies in entering and operating in the Czech business environment. In the policy mapping conducted by the OECD in 2023, approximately 70% of the policy measures were directed towards enhancing SME performance, 27% focus on attracting productivity-enhancing FDI, and 20% on strengthening agglomeration economies (total above 100% as some policies might have multiple targets (Figure 1.5, Panel A). This could imply that while Czechia’s government is working to strengthen its domestic SMEs, there might be room to increase efforts in attracting and facilitating investments from foreign companies, which could further enhance the potential for FDI spillovers on the domestic economy. When it comes to strengthening the spillover channels through which FDI affects SMEs (i.e. FDI-SME diffusion channels), Czech policies aim to primarily promote strategic partnerships (30%) between SMEs and foreign affiliates (FAs) and to foster value chain linkages (23%) (Figure 1.5, Panel B). There is a relatively lower emphasis on addressing issues related to labour mobility and competition within the policy mix (accounting for 5% of mapped policies each) (Figure 1.5, Panel B). However, this analysis does not imply less policy relevance in the areas where less measures are taken, and methodological limitations should be kept in mind in interpretation. Considering the number of policy initiatives that target these policy objectives is only a partial measure of policy focus in a given area. The policy mix analysis takes into account other aspects relating to policy design and implementation, including the sectoral and value chain targeting of implemented measures, the uptake of public support schemes, the number of beneficiaries, the quality of the regulatory environment, and the type of policy instruments used to achieve specific policy objectives, amongst others.

Czechia primarily relies on financial support, technical assistance and facilitation services to strengthen FDI linkages with domestic SMEs. Financial instruments include grants, loans, tax credits and other forms of direct or indirect funding. Technical assistance, information provision and facilitation services include a wide range of business support measures and services (e.g. consulting, business diagnostic assessments, information, matchmaking and networking, training and skills upgrading, business incubation, etc.). An important factor reflected in the chosen mix of policy instruments lies in Czechia’s emphasis on matchmaking services, industry-specific collaboration platforms and business networking events.

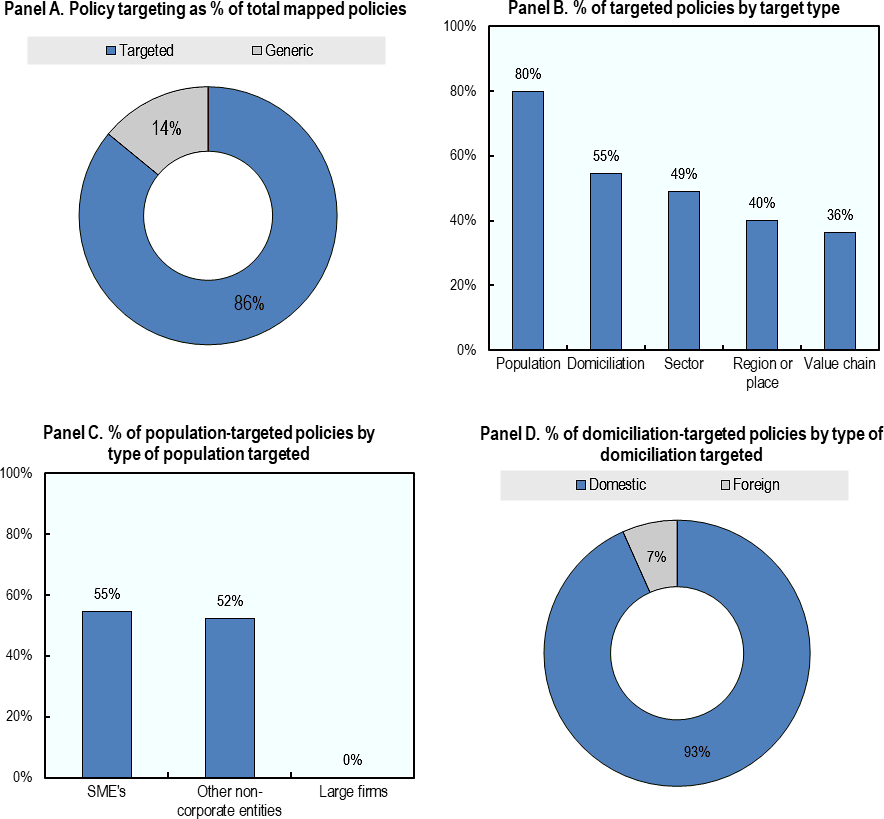

Despite the many SME support programmes, SME access to these programmes can be challenging. The delivery of these schemes is fragmented across multiple government agencies, raising barriers to SMEs access to available support. Policy initiatives are predominantly aimed at specific types of firms (e.g. startups), sectors of the economy, or sub-national areas. Initiatives tailored for SMEs also target universities and research centres with the aim to foster business-science linkages and ease the transfer of knowledge to local SMEs. Meanwhile, policies towards private investors, business angels and venture capital funds contribute to improving SMEs’ access to funding. Policy initiatives focusing on specific sectors are also an important part of the policy mix, representing 49% of targeted policies (Figure 1.6, Panel B). Czechia’s smart specialisation strategy aims to create a long-term competitive advantage by attracting more knowledge-intensive FDI and enhancing the innovation capacity of SMEs in selected priority sectors. The National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) 2021–2027 focuses on technology-intensive sectors and value chains such as advanced materials, digital and green technologies, and smart cities, which are all areas with significant potential for knowledge-based innovation and long-term growth.

Figure 1.5. Orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia and benchmarking countries

Copy link to Figure 1.5. Orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia and benchmarking countries% of mapped policy measures

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives in place. Total may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

The place-based approach of Czech policies indicates a strategic focus on the regional development of economically and socially vulnerable areas, with 40% of targeted policies taking a place-based approach (Figure 1.6, Panel B). For example, CzechInvest focuses its investment incentives on economically and socially endangered areas according to the Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ and structurally disadvantaged areas like the Moravia-Silesia, Ústí and Karlovy Vary regions. By doing so, they seek to attract FDI to these areas and foster the growth and development of local SMEs, thereby facilitating the creation of FDI-SME linkages that can contribute to regional economic resilience and prosperity.

There is a strategic emphasis on enhancing the competitiveness and integration of SMEs within different value chains in Czechia. Thirty-six percent of targeted policies focus on specific value chains (Figure 1.6, Panel B). These initiatives aim to attract FDI into sectors where Czech SMEs are active or have growth potential. This can facilitate technology transfer, enhance local capacity, and foster innovation.

Figure 1.6. Most FDI-SME policies in Czechia target specific populations, domiciliation, sectors, regions, or value chains

Copy link to Figure 1.6. Most FDI-SME policies in Czechia target specific populations, domiciliation, sectors, regions, or value chains

Note: Panel A: Shares of generic and targeted policies as a percentage of the total 64 policies mapped. Panel B: Shares of policies by target type, as percentage of total targeted initiatives (55). As policies can be directed at more than one type of target, the sum is above 100%. Panel C: Shares of policies by type of population targeted, as percentage of total population-targeted policies (44). SMEs-targeted policies include initiatives applying to SMEs only or providing preferential conditions to them. Other non-corporate entities include investors (business angels, venture capitalists or VC funds, banks, financing institutions, etc.); universities; research organisations; entrepreneurs; individuals with specific roles or skillsets (e.g. managers, highly-skilled, researchers); government institutions and sub-national governments (e.g. municipalities); and others. Panel D: Shares of policies by type of domiciliation targeted, as percentage of total domiciliation-targeted policies (30). It demonstrates distribution of policies specifically targeting domestic or foreign firms.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Recent legislative efforts have aimed at enhancing the business climate, emphasising the simplification of regulations and reduction of regulatory complexity. Czechia maintains a relatively open economy compared with other OECD countries and this market openness may facilitate the attraction of productivity-enhancing FDI, fostering an environment that is generally welcoming and non-discriminatory toward foreign investors. However, labour market regulations remain an area for improvement, and there are concerns about administrative burdens on start-ups, barriers to competition and regulations surrounding the interaction between policymakers and interest groups. For example, transparency in legislative processes could be enhanced, and concerns persist regarding bureaucratic hurdles, lengthy administrative procedures, and frequent changes to laws and programme rules.

Czechia offers a diverse range of investment incentives, from tax allowances to direct grants, designed to entice both domestic and foreign investors across various sectors, including technology, manufacturing, the production of strategic products, and business support services. The set of instruments used is more diversified than in some peer countries. Czechia’s policy framework includes the differentiation of incentives based on the scale of investment, targeted sectors, and regional needs, addressing the varied demands of investment projects and regional economic conditions. For example, CzechInvest’s investment incentives for manufacturing or for technology centres include corporate income tax (CIT) relief for up to 10 years, job creation grants as well as training and retraining grants, conditioned to a minimum investment size, certain level of added value, and an exclusive availability in districts with an unemployment rate of at least 7.5%. However, in current economic situation with extremely low unemployment rate these cash grants are almost unobtainable and their conditions should be revised. The investment incentives for the production of strategic products is similar with a cash grant of up to 20% of eligible costs conditional to a minimum investment size.

There is room to strengthen public support to business R&D which is currently below the OECD and EU average. The Czech government supports business R&D through comprehensive legislative strategies such as the Innovation Strategy of the Czech Republic 2019–2030, which was endorsed by the government in February 2019. The largest share of public support to business R&D takes the form of grants or loans for R&D and innovation or internationalisation activities; business consulting and training services; or technology acquisition and digitalisation. Czechia has made progress in diversifying its traditional investments in engineering into new fields of R&D and innovative technologies. According to the Czech Statistical Office, in 2022, R&D spending rose by 9.3% year-on-year to a record CZK 133.3 billion mainly due to R&D investment by businesses. However, despite the significant potential of some domestic research organisations and infrastructures, the overall quality and performance of public R&D still has room for improvement.

Several Czech policies and programmes adopt a place-based approach, especially in the support provided to business enterprises in the fields of R&D and innovation. This is the case for investment incentives available to domestic and foreign investors, and certain SME R&D and innovation programmes supported by the EU Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF). However, most FDI-SME policies are applied equally across all Czech regions, with few targeting specific regions for preferential treatment. Direct innovation support, such as grants, in Czechia is generally provided from the national level and it is mostly funded from the ESIF and a few national programmes, while indirect support in the form of advisory services (mentroing and coaching, match-making services) is provided regionally through regional innovation centres. There could be more emphasis on innovation and technology diffusion around regional development policies, with a deeper involvement of subnational offices of the main implementing agencies, conditional on the allocation of the additional resources of these subnational offices, and regional innovation agencies. Strengthening the linkages between regional development action plans and the needs of local FDI-SME ecosystems is crucial and could be done, for example, by enchancing mechanism through which regional development agencies interact with business associations and industry representatives at the local level.

The establishment and development of cluster organisations has been actively supported by several institutions, including the MIT, CzechInvest, and the National Cluster Association (NCA). MIT plays a significant role in supporting the expansion of Czech companies abroad and the development of clusters through the Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Crafts of the Czech Republic (AMSP CR). CzechInvest facilitates FDI and local start-ups, implements business development programmes, and in cooperation with MIT provides support to clusters and industrial parks. The NCA brings together entities and individuals with the goal of coordinated and sustainable development of industry-specific cluster initiatives.

The impact of FDI-SME spillovers resulting from labour mobility hinges on the effectiveness of labour market regulations. The labour market policy in Czechia has focused on removing domestic barriers to labour market participation and addressing labour and skill shortages. According to the 2023 EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages, regulatory measures are the only type of policy instrument deployed to facilitate the mobility of skilled workers from foreign affiliates of MNEs to local SMEs. These measures intend to simplify visa application procedures for hiring skilled foreign workers in sectors of strategic importance. Even though regulatory measures are important to set rules and standards, a multi-faceted approach that includes technical assistance, information and facilitation services, financial support schemes, and a strong governance framework can provide a more comprehensive and effective solution to improve labour mobility.

Labour mobility also relies on the presence of policies and programmes that promote the transition of employees from foreign MNEs to local companies. Enhancing collaboration between domestic SMEs and affiliates of foreign MNEs operating locally is a priority objective for Czechia, which mainly does so by supporting value chain linkages and strategic partnerships. There are also multiple policies aimed at bridging the skills gap to strengthen FDI-SME linkages such as educational initiatives, incubation programmes, international exposure, and investment incentives. Despite existing policies targeting the upskilling of the SME population, further support for the diffusion of emerging technologies could be beneficial for SME as well as for MNEs. More industry-specific training programmes, particularly for sectors crucial to the Czech economy, could be also developed.

Box 1.2. Recommendations on the policy mix

Copy link to Box 1.2. Recommendations on the policy mixIncrease the focus on attracting FDI in high-technology and knowledge-intensive sectors, particularly by shifting investment incentives towards grants and tax relief measures that support productivity growth and involve science-to-business collaboration.

Simplify administrative processes for technology-intensive investments, especially those in collaboration with Czech R&D institutions, to make Czechia more attractive for these investments.

Enhance the capabilities of SMEs to absorb new technologies and innovations by expanding access to technical assistance, capacity-building, and innovation funding schemes.

Reduce administrative burden for SMEs. Transparency in legislative processes could be enhanced and efforts could be made to minimise bureaucratic hurdles, lengthy administrative procedures, and frequent changes to laws and programme rules.

Encourage partnerships between academia, research institutions, and industry to foster innovation and technology transfer, by advocating for a more flexible interpretation of the EU State Aid Framework for R&D & Innovation on the use of R&D infrastructures by business enterprises.

Strengthen the integration and coordination between various policy measures, reducing administrative fragmentation and ensuring harmonisation across different sectors and regions.

Address labour market rigidity and enhance skills development to provide SMEs with access to a skilled workforce, essential for maximising the benefits of FDI. Provide technical assistance and information & facilitation services to businesses and foreign specialists. These services can provide necessary training and skills development, helping workers adapt to new job markets and technologies.

Support the development of industrial clusters through multi-year sectoral action plans involving both public and private sector interventions, aimed at addressing growth bottlenecks.

Pursue a smart specialisation strategy by focusing on sectors where Czechia has or can develop a competitive edge, aligning FDI attraction with national and regional strengths.

Cluster and expand initiatives like Sectoral Database of Suppliers, Czech Business Partner Search, and the Exporter's Directory into one functional program with proper funding and insure the sufficient cooperation and coordination among the institutions involved to promote supplier linkages and partnerships between foreign MNEs and Czech SMEs, particularly in knowledge-intensive value chains.

Improve SMEs' access to finance and technical support, especially for start-ups and smaller firms, by simplifying access to existing financial support schemes and enhancing the technical assistance offered to SMEs.

Implement a more balanced regional development approach by initiating and sustaining a multi-level dialogue between national authorities and regional stakeholders to identify and target the types of FDI that align with regional development goals to reduce disparities by promoting FDI in less developed regions, fostering equitable growth across all regions. Ensure policies for attracting knowledge-intensive investment and upgrading SMEs are integrated into regional and local development strategies, promoting a place-based approach to investment and innovation.

1.5. Applying a regional lens: Ústí nad Labem and South Moravia

Copy link to 1.5. Applying a regional lens: Ústí nad Labem and South MoraviaA regional approach can help strengthen FDI and SME linkages in Czechia by taking into account the country's diverse economic and social landscapes. On the one hand, tailoring FDI attraction strategies to regional specificities can enhance the innovation and growth potential of local SMEs, primarily by creating environments that promote knowledge spillovers and technology transfer. On the other hand, strengthening the right regional conditions can also help leverage SME growth through foreign investments and support higher value-added activities, strengthening the regional business ecosystem and leading to the internationalisation of local economies.

The Ústí nad Labem and South Moravia regions have distinct geographic, economic and demographic features that are relevant to attract innovative FDI and SMEs. Ústí nad Labem is in the midst of an economic transition, aiming to diversify and modernise its traditionally industrial sectors, notably mining and manufacturing. In contrast, South Moravia stands out for its vibrant innovation ecosystem, IT, and services sectors and the presence of advanced research institutions and universities in Brno.

Both regions can benefit from better digital and transport infrastructure to help capitalise their geographical location to attract FDI with strong spillover potential.

Improved internet fibre rollout is warranted given that the penetration rate of fiber optic in Czechia (7.6%) is almost half of the OECD average (13.2%) (OECD, 2023[2]). Expanding this infrastructure is vital to firms in accessing digital business tools needed to remain competitive in today's economy. Beyond improving infrastructure, improved digital literacy can support SMEs to transition to more innovative industries, and the public administration to simplify administrative procedures for international investments.

Greater investments in cross-border programmes can better connect internal markets with large bordering European markets (Austria, Germany, Poland, Slovak Republic), offering trade opportunities and new connections for the local economies.

There is scope to improve cooperation across municipalities within regions to enhance public service delivery and coordinate development strategies to increase attractiveness for FDI and international workers. Czechia records the highest degree of municipal fragmentation across OECD (average area of a Czech municipality is 13 km², significantly smaller than the OECD average of 234 km). This municipal fragmentation has led to siloed investments in public services resulting in a lack of economies of scale and scope, for example in technical and administrative capacities.

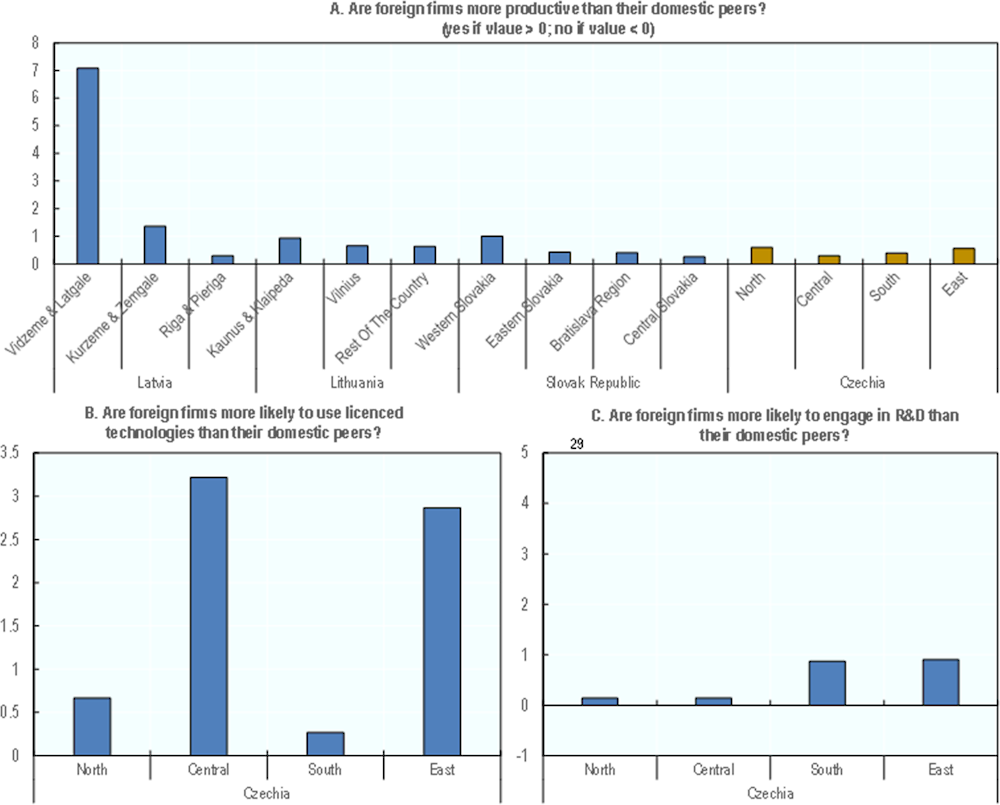

There is also an untapped opportunity to better link local businesses with foreign companies, thereby promoting knowledge and technology spillovers. The productivity gap between foreign companies and local firms in these two regions is relatively higher than the rest of the country, yet it remains lower than that observed in several OECD countries, such as Latvia, Lithuania, and the Slovak Republic (Figure 1.7). For example, the ‘North’ region, which includes Ústí nad Labem, demonstrates a foreign firm productivity premium of about 0.595 – indicating a larger gap between the productivity of foreign versus domestic firms – while the ‘South’ region, containing South Moravia, has a premium of around 0.394. These figures imply that foreign firms are making a positive contribution to productivity in these areas and could represent an opportunity for local businesses to learn and adopt new technologies and practices. However, realizing this potential requires a supportive policy environment that encourages collaboration and technology transfer between firms. Establishing local 'one-stop shops' could streamline administrative processes, providing easier access to regional, national, and European support programmes, and extending comprehensive support to SMEs that goes beyond financing. Such measures would enhance their capacity to innovate, scale-up, and ultimately increase their productivity.

In Ustí nad Labem there is scope to better map and brand regional economic characteristics to align local strengths with the needs of international companies. While the region is diversifying from its industrial legacy towards higher value-added industries, it struggles to be perceived as an attractive destination for highly skilled workers due to its historic mining and migration legacy. Thus, a regional branding strategy can leverage the competitive advantages of the region, including the lower cost of living, access to a large set of brownfields (around 4,000 only in Usti), and proximity to the German market amongst others. Furthermore, in Ústí nad Labem, the polycentric settlement patterns require additional efforts to promote cooperation across development plans and strategies of the different cities to attract and link FDI with local business. A platform for city cooperation could help the region improve its attractiveness by achieving better public service delivery and reaching a common vision for local development, including FDI attraction and local SME ecosystem development (see Box 1.3).

In the case of South Moravia, the region could further mobilise its innovation-led business ecosystem to promote inclusive development beyond Brno. While South Moravia's focus on attracting FDI in high value-added activities is well-supported by its infrastructure and educational framework, greater collaboration is needed between academia, public and private sectors to further diffuse foreign know-how and technology into the local economy. The collaboration on R&D projects, particularly in burgeoning fields such as advanced manufacturing or biotechnology, is vital for fostering innovation. In South Moravia, for instance, the synergy between the biotech research at Masaryk University and local SMEs has already yielded positive results (Masaryk University, 2024[3]). Engaging companies in educational initiatives, such as structured internships, joint research programmes, and innovation workshops, allows for the direct application of academic research to industry challenges. For instance, in Ústí nad Labem, the Unipetrol Centre for Research and Education (UniCRE) collaborates deeply with academic institutions, including the University of Jan Evangelista Purkyně. Their focus areas include research activities supporting the chemical industry, with goals like integrating into European research structures and promoting science and development (Unicre, 2022[4]).

Figure 1.7. Labour productivity and innovation performance of foreign firms by region in Czechia and selected peer economies, 2022

Copy link to Figure 1.7. Labour productivity and innovation performance of foreign firms by region in Czechia and selected peer economies, 2022

Note: North region is a proxy for Usti nad Labem and South for South Moravia.

Source: Czech Statistical Office (2020[5]) https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/home

Box 1.3. Policy recommendations to improve FDI-SMEs linkages in the regions of Ústí nad Labem and South Moravia

Copy link to Box 1.3. Policy recommendations to improve FDI-SMEs linkages in the regions of Ústí nad Labem and South MoraviaEstablishing a collaborative platform for regional development in Ústí nad Labem, fostering a joint vision to attract FDI and integrate it effectively with the local economy. This initiative could be spearheaded by the regional office and encourage synergistic policy and resource alignment, enhancing coordination among the region's three Functional Urban Areas to foster a larger, integrated economic and social ecosystem.

Improving regional branding to better promote the competitive advantage of the regions for international firms and workers. It involves investing in regional branding initiatives that accurately reflect the unique regional advantages (e.g., lower living cost compared to the capital city, environmental amenities among others) and promote available job and career opportunities to attract talent.

Enabling regional governments and municipalities to lead redevelopment initiatives for brownfields, transforming them into hubs of innovation and entrepreneurship. This is of special relevance for Ústi nad Labem due to its high stock of brownfields (over 4 thousand). For this, the national government and the regions should build on the National Brownfield Regeneration Strategy and assist coordination between municipalities and investors to facilitate new business developments.

Leveraging its strategic position of border regions in Czechia. It could be done by developing cross border programs with neighbouring countries (Germany, Austria and Slovak Republic) to i) benefit SMEs by facilitating easier access to cross-border supply chains, expanding customer bases, and fostering collaborative opportunities with foreign partners and to ii) develop programs for academic partnerships across educational institutions.

Facilitating business services beyond financing to provide comprehensive support for local SMEs and investors. It can be done through a regional 'one-stop shop' for business support to provide administrative guidance and information about innovation opportunities, connect firms and university projects or EU funds and regional programmes.

Better linking universities and research centers with business to strengthening the regional innovation ecosystem. This should involve setting up contact points or joint forums to align business needs with the research agendas of local academic institutions, such as the University of Jan Evangelista in Ústí nad Labem and the Brno Technological Park.

Promoting inter-municipal cooperation on public service delivery to enhance regional attractiveness for FDI. Such collaboration could lead to better healthcare, education, and infrastructure development, as well as streamlined administrative processes, creating a more welcoming environment for both local and international enterprises and talent.

References

[11] Alfaro, L. and M. Chen (2012), “Surviving the Global Financial Crisis: Foreign Ownership and Establishment Performance”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 4(3): 30-55.

[5] CZSO (2020), Czech Statistical Office, https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/home (accessed on 2023).

[10] Helpman, E., M. Melitz and S. Yeaple (2004), “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms”, American Economic Review, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/melitz/files/exportsvsfdi_aer.pdf.

[12] Johanson, J. and J. Vahlne (1977), “The internationalization process of the firm - A model of knowledge development and increasing market commitments”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. Vol. 8, No. 1.

[3] Masaryk University (2024), We work with the private sector, https://www.muni.cz/en/cooperation/partnership/partnership-with-companies.

[2] OECD (2023), OECD Broadband statistics, https://www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/broadband-statistics/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

[13] OECD (2023), Policy Toolkit for Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/688bde9a-en.

[1] OECD (2022), “Trade by enterprise characteristics: Trade by ownership (domestic or foreign) (Edition 2022)”, OECD Statistics on Measuring Globalisation (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/3d347a3e-en (accessed on 8 January 2024).

[6] OECD (2021), OECD SME and Enterpreneurship Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[9] OECD (2020), Enabling FDI diffusion channels to boost SME productivity and innovation in EU countries and regions: Towards a Policy Toolkit, Concept Paper for joint EC-OECD project..

[7] OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d2b72934-en.

[8] OECD (2018), Promoting innovation in established SMEs, OECD SME Ministerial Conference, Mexico City, Policy Note, 22-23 February 2018, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Parallel-Session-4.pdf.

[4] Unicre (2022), MIssion and Goals, https://www.orlenunicre.cz/en/.

Annex 1.A. FDI spillovers on SMEs: conceptual framework

Copy link to Annex 1.A. FDI spillovers on SMEs: conceptual frameworkFDI is an important source of finance for developed and developing countries and can play an important role in supporting a resilient and sustainable recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Harnessing FDI for sustainable development, and particularly productivity and innovation, requires strong linkages with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in host countries. Foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) do not just choose countries but locations in specific sub-national regions, and hence, FDI-SME linkages need to be considered and strengthened through place-based approaches.

SMEs contribute significantly to economic growth and social inclusion, and they can also play a key role in building resilience and more sustainable growth during the post COVID-19 recovery. In the OECD area, SMEs account for almost all enterprises, about two-thirds of total employment and 50-60% of value added (OECD, 2021[6]). To achieve their full potential, SMEs need to increase productivity and scale up innovation capacity. They are often less productive and innovative than larger firms where size is often identified as a major barrier to higher performance. Yet, some SMEs can be more productive and innovative than large firms, signalling that size is no fatality. In digital-intensive sectors, for example, smaller firms can show higher productivity levels (OECD, 2019[7]). SMEs play a key role in shifting innovation models by adapting supply to different contexts or user needs and responding to new or niche demand (OECD, 2018[8]).

Changes in the global trading and investment environment offer new opportunities for SME upgrading. Participation in global value chains (GVCs) enables SMEs to enhance productivity by absorbing technology and knowledge spillovers, upgrading workforce and managerial skills and raising innovation capacity (OECD, 2018[8]). This can be achieved by linking their business activities with foreign affiliates of MNEs (and domestic owned companies) and/or by directly integrating in GVCs as exporters, i.e. by supplying companies located abroad.

In this context, beyond the contribution to capital investment and employment generation, FDI can play an important role for knowledge and technology spillovers in host economies, resulting in increased productivity of local firms, especially SMEs. While productivity and innovation capacity of SMEs are influenced by a variety of market, policy and other factors (OECD, 2019[7]; OECD, 2021[6]), this report focuses on the specific role of FDI and related policies in Czechia. This introductory chapter introduces the conceptual framework to assess FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs and outlines how this framework is implemented for the case of the Czechia (OECD, 2020[9]).

The conceptual framework to assess FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs

Copy link to The conceptual framework to assess FDI spillovers on domestic SMEsSpillovers from FDI on domestic SMEs depend on a set of main enabling factors:

Potential for FDI spillovers: FDI spillovers are possible as foreign firms are often more productive than domestic ones. Foreign MNEs are often larger than domestic firms, where size is found to be associated with higher productivity and a key determinant to overcome fixed costs for investment abroad (Helpman, Melitz and Yeaple, 2004[10]). Affiliates of foreign firms – through their links with parent companies – have typically greater access to technology, better managerial skills and more adequate resources for capital investment than domestic firms (Alfaro and Chen, 2012[11]). These capacity differences between foreign and domestic firms make it possible for SMEs to benefit from knowledge and technology transfers. The potential for FDI spillovers is further influenced by the volume of FDI inflows (i.e. the economy’s relative dependence on FDI) and a number of FDI characteristics that illustrate to what extent FDI is effectively embedded in the local economy. These characteristics include (a) the sector in which the investment occurs and the activities that the foreign company undertakes, (b) the main motivations behind the FDI decision (e.g. market-seeking, resource-seeking, asset-seeking, efficiency-seeking), (c) the type of FDI (e.g. greenfield versus mergers and acquisitions), (d) the country of origin of the foreign investor, including the geographical and cultural proximity to the receiving country and the degree of foreign ownership.

Absorptive capacities of domestic SMEs: Absorptive capacity refers to the ability of a firm to recognise valuable new knowledge and integrate it productively in its processes, i.e. to innovate (OECD, 2021[6]; 2019[7]). The stronger its absorptive and innovative capacity, the higher its chances to benefit from FDI. SME absorptive capacity depends on the firm’s prior capital endowment and level of productivity, i.e. its level of financial, human and knowledge-based capital and its efficiency in creating value from it. Beyond existing endowments of these resources, absorptive capacity also depends on SMEs’ ability to access strategic assets related to finance, skills and innovation as well as on the broader business environment. Not all SMEs are the same and their heterogeneity greatly contributes to explain their performance. SMEs vary in terms of age, size, business model, market orientation, sector and geographical area of operation. This means that different types of SMEs have different growth trajectories and therefore different chances to enter into knowledge sharing relationships with foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) and to benefit from FDI spillovers.

Economic geography factors: This refers to geographical and cultural proximity factors, where the latter is defined by factors such as the differences between home and host countries in terms of language, culture, political systems, level of education, and level of industrial development (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977[12]). The localised nature of FDI means that geographical and cultural proximity between foreign and domestic firms affects the likelihood of knowledge spillovers, which often involve tacit knowledge, and whose strength decays with distance. Thus, productivity spillovers from FDI on local firms are often concentrated in the same region of the investment. Agglomeration effects, notably through the presence of local industrial clusters, have also been reported to affect FDI attraction and FDI spillovers. Clusters embed characteristics such as industrial specialisation (through specialised skilled workers and suppliers) and geographical proximity that make knowledge spillovers more likely to happen, including from MNE operations.

Other economic and structural characteristics of the host country: The degree to which FDI-SME spillovers materialise also depends on other economic and structural characteristics of the host country and its sub-national regions. These factors relate to the regional/national endowment as well as the macro-economic context, structure of the economy, sectoral drivers of growth, productivity and innovation as well as to the level of integration in the global economy, beyond FDI. These factors are often necessary conditions for FDI spillover potential, SME absorptive capacity and economic geography factors to turn into actual productivity gains for domestic SMEs.

While adequate enabling conditions are necessary, FDI spillovers only occur if domestic SMEs are exposed to MNE activities. Such exposure may occur through a set of diffusion channels:

Value chain linkages involve knowledge spillover from foreign MNEs to suppliers (upstream) and customers (downstream). Linkages help domestic companies extend their market for selling and raise the quality and competitiveness of their outputs. They can also generate knowledge spillovers when MNEs require better-quality inputs from local suppliers, particularly SMEs, and are therefore willing to share knowledge and technology with domestic companies to encourage their adoption of better practices.

Strategic partnerships involve knowledge and capacity transfer in formal collaborations, for example in the area of R&D or workforce/managerial skills upgrading. These partnerships can take many forms, including joint ventures, licensing agreements, research collaborations, globalised business networks (i.e. membership-based business organisations, trade associations, stakeholder networks), and R&D and technology alliances.

Labour mobility can be an important source of knowledge spillovers in the context of FDI, notably through the move of MNE workers to local SMEs – either through temporary arrangements such as detachments or long-term arrangements such as open-ended contracts – or through the creation of start-ups (i.e. corporate spin-offs) by (former) MNE workers. Firms established by MNE managers are often more productive than other local firms. Similarly, workers who moved from foreign-owned to domestic firms retain skills and competences, including management skills, acquired in the foreign firms and thus contribute more to the productivity of their firm than workers without foreign firm experience.

Competition effects occur with the entry of foreign firms, which heightens the level of competition on domestic companies and puts pressure on them to become more innovative and productive – not least to retain skilled workers. The new standards set by foreign firms – in terms of product design, quality control or speed of delivery – can stimulate technical change, the introduction of new products, and the adoption of new management practices in local companies, all of which are possible sources of productivity growth. This rising competitive pressure due to foreign firm entry and related productivity spillovers may also be associated with new incentives for workers to improve skills and SMEs to engage in skills upgrading.

Imitation effects occur when foreign firms can also become a source of emulation for local companies, for example by showing better management practices. Imitation, reverse engineering and tacit learning can therefore become a channel to strengthen enterprise productivity at the local level. Foreign firms may also participate in innovation clusters and collaborative innovation activities where cross-fertilisation of ideas can increase productivity, both of domestic and foreign firms.

The scope for productivity and innovation spillovers on domestic SMEs is ultimately determined by the interaction of enabling factors and diffusion channels. Public policies aiming to enhance these spillovers address these different aspects and cut across a range of policy domains, including investment policy and promotion, SME development, innovation and regional development.

Annex Figure 1.A.1. Understanding FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs: conceptual framework

Copy link to Annex Figure 1.A.1. Understanding FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs: conceptual framework

Source: OECD (2023[13]), Policy Toolkit for Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages, https://doi.org/10.1787/688bde9a-en.