This chapter examines the extent of FDI and SME linkages in Czechia and the potential for the diffusion of knowledge, technology and skills from foreign multinationals to domestic SMEs. It examines where Czechia stands in the core channels of FDI-SME diffusion – namely value chain relationships; strategic partnerships; labour mobility; and competition and imitation effects – relative to peers in the OECD and the European Union and across economic activities.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Czechia

3. FDI spillovers at play for Czech SMEs

Copy link to 3. FDI spillovers at play for Czech SMEsAbstract

3.1. Summary of findings

Copy link to 3.1. Summary of findingsFor FDI-SME spillovers to occur, domestic SMEs should be exposed to activities of foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) either directly or indirectly. When SMEs are exposed to MNE activities they form linkages. Strengthening these linkages enhances productivity spillovers through the diffusion of knowledge, technology and skills to domestic firms, and by improving the innovative and scale-up capabilities of SMEs. This chapter explores Czechia’s core channels of FDI-SME diffusion, namely value chain relationships, strategic partnerships, labour mobility, competition and imitation effects.

Foreign MNEs can obtain intermediate inputs from local suppliers (i.e. supplier linkages) or by importing from abroad. Opting to source inputs locally creates opportunities for growth for domestic firms, in particular SMEs. In Czechia, foreign affiliates import almost half (46% vs 37% at the OECD) of their intermediate inputs and source significantly less inputs locally compared to most OECD economies. This trend is observed across other small EU countries, including Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies, while foreign MNEs operating in larger economies like Germany and Italy tend to rely more on local suppliers due to the size of their domestic markets. Domestic-owned firms are responsible for almost one third (32%) of the inputs sourced by foreign affiliates. Although the majority of them are non-multinational firms – a category that likely includes most Czech SMEs –, their contribution to foreign affiliates’ sourcing structure is lower than that of domestic-owned firms in the OECD area, which are on average responsible for half of the sourced inputs. In contrast, other foreign affiliates operating in Czechia are more important sources of intermediate inputs (23% of total sourcing vs 13% at the OECD), suggesting some clustering of foreign affiliates in Czechia, which tend to buy from and supply each other.

Similarly, foreign affiliates’ output is mostly exported or sold to other foreign affiliates operating in the Czech market, indicating a lower potential for FDI-SME spillovers through buyer linkages. Such linkages are often a source of productivity spillovers because they allow domestic firms to access new, higher-quality or cheaper intermediate inputs. Many MNEs also offer training to their customers on the use of their products and provide information on international quality standards.

Beyond supplier-buyer linkages, foreign MNEs and domestic SMEs can establish strategic partnerships around the development of joint R&D and innovation projects, which can create opportunities for technology transfer, especially in high-technology and knowledge intensive industries. In Czechia, foreign MNEs and domestic SMEs establish cooperation through strategic partnerships in R&D and innovation particularly in high-technology and knowledge-intensive industries. Overall engagement in cooperation among Czech firms is moderate, with smaller enterprises lagging behind larger ones. Strategic partnerships particularly with foreign firms are less common among smaller Czech firms, indicating potential challenges in fostering linkages with FDI. Although Czech firms engage in technology licensing agreements at levels comparable to or higher than many comparator economies, foreign firms in Czechia appear to be less involved in such partnerships compared to their counterparts elsewhere.

Labour mobility can serve as a channel for knowledge spillovers, particularly through the movement of MNE workers to local SMEs. In Czechia, however, job-to-job mobility is lower than in many peer economies, especially in science and technology related sectors. While job mobility within the local labour market is limited, conditions for mobility of highly skilled foreign workers are relatively restrictive, with less favourable permit duration and labour market mobility conditions compared to neighbouring countries. Moreover, wages in foreign firms are significantly higher than in domestic firms especially in the services industry (e.g. information and communication, finance, and professional services), discouraging labour mobility and associated skills spillovers to domestic firms. The potential for FDI-SME spillovers through labour mobility also depends on FDI’s skills intensity, as well as training and learning opportunities that SMEs have in the domestic economy, amongst other factors. Czechia is among the few countries, where foreign firms do not outperform their domestic counterparts in terms of training opportunities. This could be linked to the concentration of FDI in sectors creating few highly-skilled jobs such as the capital-intensive real estate and finance sectors as well as in low-value added manufacturing linked to assembly and processing, which may not always require highly specialised and technology-intensive skills.

FDI-SME spillovers may also materialise through market interaction mechanisms driven by competition and imitation effects. Competition effects arise when MNEs enter the market, influencing domestic companies operating in the same sector or value chain segment, even if not geographically located in the same region. Conversely, imitation effects occur at a more local level when domestic firms emulate the practices of foreign MNEs, leading to enhancements in their productive and innovative capacities. In Czechia, cooperation with competitors on innovation is relatively common, suggesting potential for FDI-SME spillovers through tacit learning. However, same sector cooperation on innovation, particularly with foreign firms, is notably lower compared to other peer economies. A considerable share of SMEs in Czechia perceives competition as a barrier to innovate. This perception may reflect challenges in keeping up with new and potentially higher quality standards set by competitors, potentially resulting in fewer knowledge spillovers from foreign companies through imitation effects.

3.2. Value chain linkages between foreign MNEs and domestic SMEs

Copy link to 3.2. Value chain linkages between foreign MNEs and domestic SMEsDomestic Czech firms may benefit from the presence of affiliates of foreign MNEs through buy and sell linkages. Domestic backward linkages are formed when foreign affiliates source intermediate inputs from locally established companies. Foreign affiliates can also sell intermediates to local companies. These linkages are referred to as domestic forward linkages (OECD, 2023[1]). This section examines domestic backward and forward linkages of foreign affiliates in Czechia. Box 3.1 clarifies the conceptual relationship between foreign firms’ sourcing, value added and output, relevant to the analysis in this section.

3.2.1. Foreign MNEs source less domestically than their peers in OECD economies

Foreign MNEs established in the host economy can purchase their intermediate inputs from local suppliers or import them from abroad. The decision of a foreign MNE to source inputs for its production from local firms, can open new opportunities for domestic SMEs.1 For example, purchases of local firms’ products by a MNE boosts demand for local firms’ products. Through interactions with MNE clients and the need to fulfil a set of associated requirements, local firms may also improve the quality of their products, introduce new management and organisational practices, and reap additional reputational gains over time (see Alfaro-Urena, Manelici and Vasquez (2022[2])). These changes can, in turn, facilitate acquisition of new clients and increasing sales to other firms in the future.

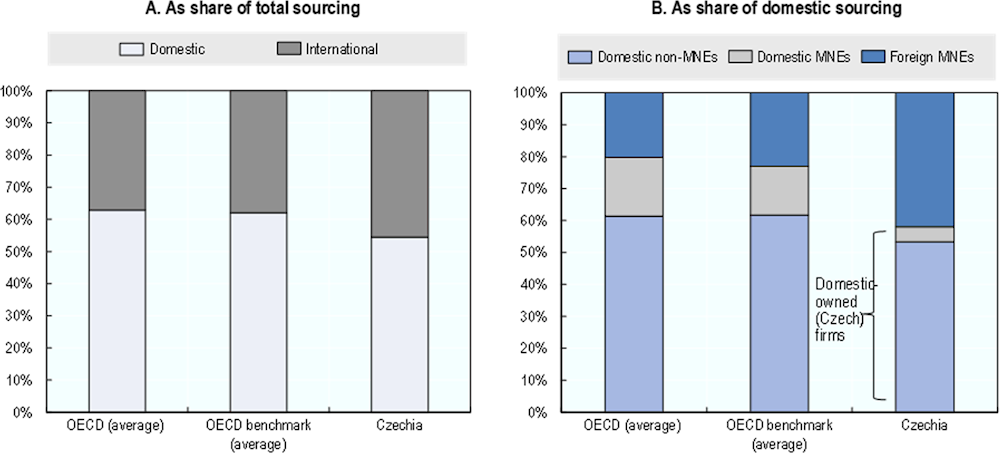

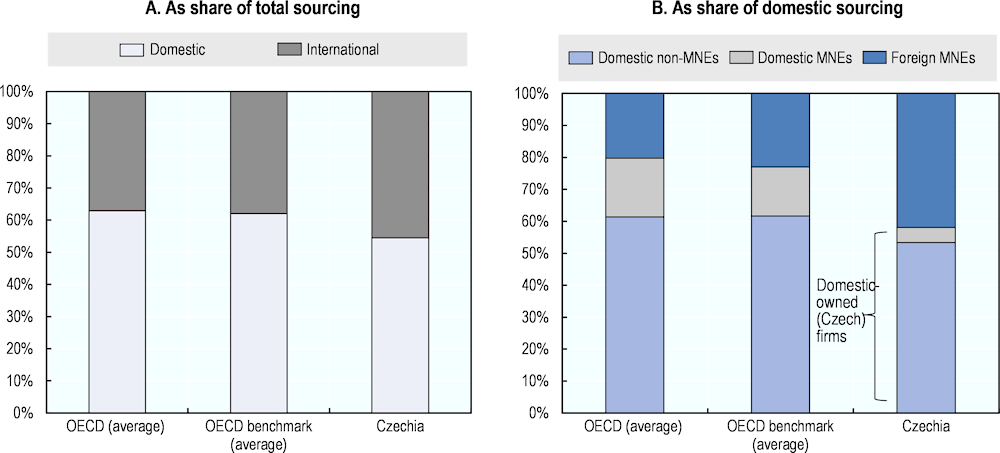

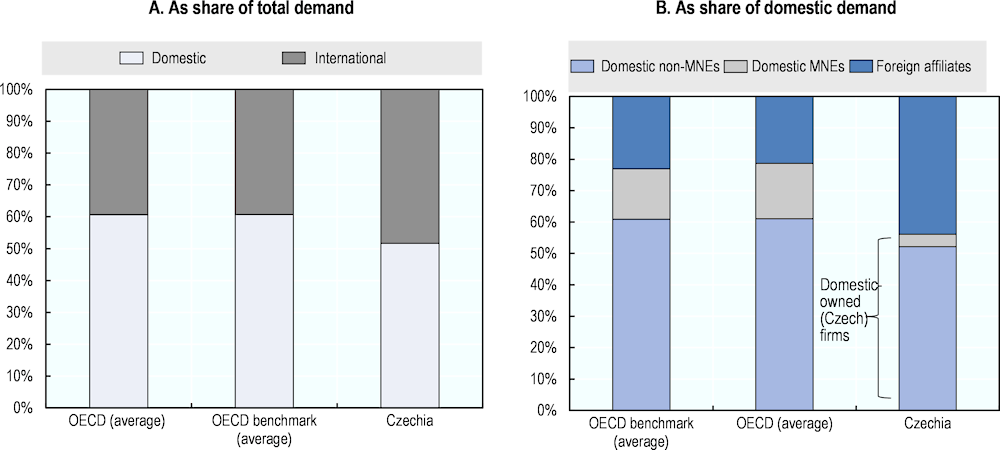

Foreign affiliates in Czechia source lower shares of their inputs locally than foreign affiliates in other small OECD economies, pointing to potentially weak supply chain linkages with the local economy. Though, domestic sourcing of intermediate inputs is more common among domestic firms than among foreign firms. On average, 46% of intermediate inputs of foreign affiliates located in Czechia was sourced via imports in 2016, while the rest was sourced domestically. These patterns are comparable to the average of benchmark OECD economies and of the OECD as a whole (Panel A in Figure 3.2). Foreign affiliates in many smaller OECD economies, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), source a similar share of their inputs from abroad via imports: 48% in the Slovak Republic and 43% in Lithuania. Meanwhile, foreign affiliates in larger economies, like Poland, Germany, or Italy, tend to purchase more inputs from local suppliers. This reflects, among others, the size of domestic markets and the availability of a larger variety of intermediate goods and services locally.

Domestic sourcing of foreign affiliates can be further decomposed into sourcing from domestic-owned and from foreign-owned firms. On average, 58% of domestic intermediate purchase of foreign affiliates in Czechia was supplied by domestic-owned firms (Panel B in Figure 3.2). This compares to 77% of domestic sourcing in benchmark OECD economies and to almost 80% for the OECD as a whole. As such, foreign MNEs established in Czechia are relatively more important as sources of intermediate inputs for foreign affiliates (42%) than in comparator OECD countries, suggesting some clustering of foreign affiliates which tend to buy from and supply to each other. Domestic non-MNEs, in turn, account for most of domestic sourcing from domestic-owned firms relative to MNEs (92% vs. 8% compared to 80% and 20%, respectively, among OECD peers).

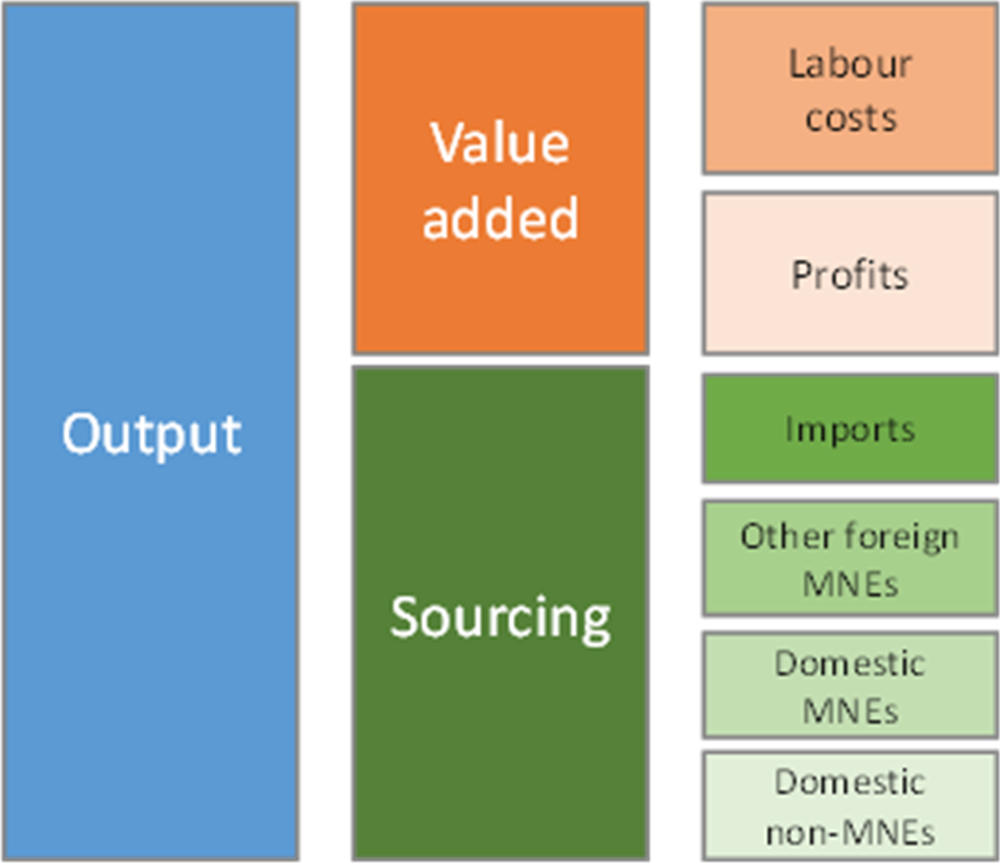

Box 3.1. Foreign affiliates’ output, value added and sourcing: relevant concepts

Copy link to Box 3.1. Foreign affiliates’ output, value added and sourcing: relevant conceptsTo understand value-chain linkages between foreign affiliates and local firms through the optic of data presented in this chapter, it is important to clarify how firm output, value-added and sourcing relate to each other. Firms’ output can be split into value added and sourcing of intermediate inputs (Figure 3.2). Foreign-owned and domestic firms can differ in their sourcing patterns in general and across sectors.

Overview of different components of firms’ output

Figure 3.1. Overview of different components of firms’ output

Copy link to Figure 3.1. Overview of different components of firms’ output

This section focuses on the extent to which foreign firms source intermediates directly from firms established in Czechia as opposed to sourcing of inputs from abroad through imports. In addition, the domestic sourcing structure is therefore further split into sourcing from other foreign affiliates established in Czechia, domestic MNEs (i.e., Czech firms with establishments abroad) and domestic non-MNEs (i.e., Czech firms with no establishments abroad).

The section does not focus on better understanding to what extent value added generated by foreign affiliates stays in Czechia or may be repatriated to home economies, which is also of key interest in the context of the direct contributions that foreign firms have on the growth and development of the host economy. Part of foreign affiliates’ value added is used to pay salaries of their (mostly local) employees and therefore “stays” in the domestic economy. The remaining part, including earnings, may or may not leave the host economy. The latter is particularly important in the context of tax policy.

Source: OECD based on (Cadestin et al., 2019[3])

Figure 3.2. Sourcing of foreign affiliates in Czechia and the OECD, by type of sourcing and type of local suppliers, 2016

Copy link to Figure 3.2. Sourcing of foreign affiliates in Czechia and the OECD, by type of sourcing and type of local suppliers, 2016

Note: The OECD benchmark countries used in this report are: Finland, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, and Slovak Republic.

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database, www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

While data splitting these different categories between SMEs and non-SMEs is not available, the shares reported above are indicative of a potentially important contribution of Czech SMEs to local sourcing of foreign affiliates in Czechia. This is because firms that belong to international business groups – based on patterns encountered in empirical studies on characteristics of firms involved in international operations across different countries – tend to be larger than other firms, on average2. While these patterns may differ across sectors (e.g., with potentially higher incidence of SMEs with MNE status in digital and other services sectors), generally, SMEs are likely to belong to the domestic non-MNE category (Cadestin et al., 2019[3]), responsible for the highest share of foreign affiliates domestic sourcing in Czechia.

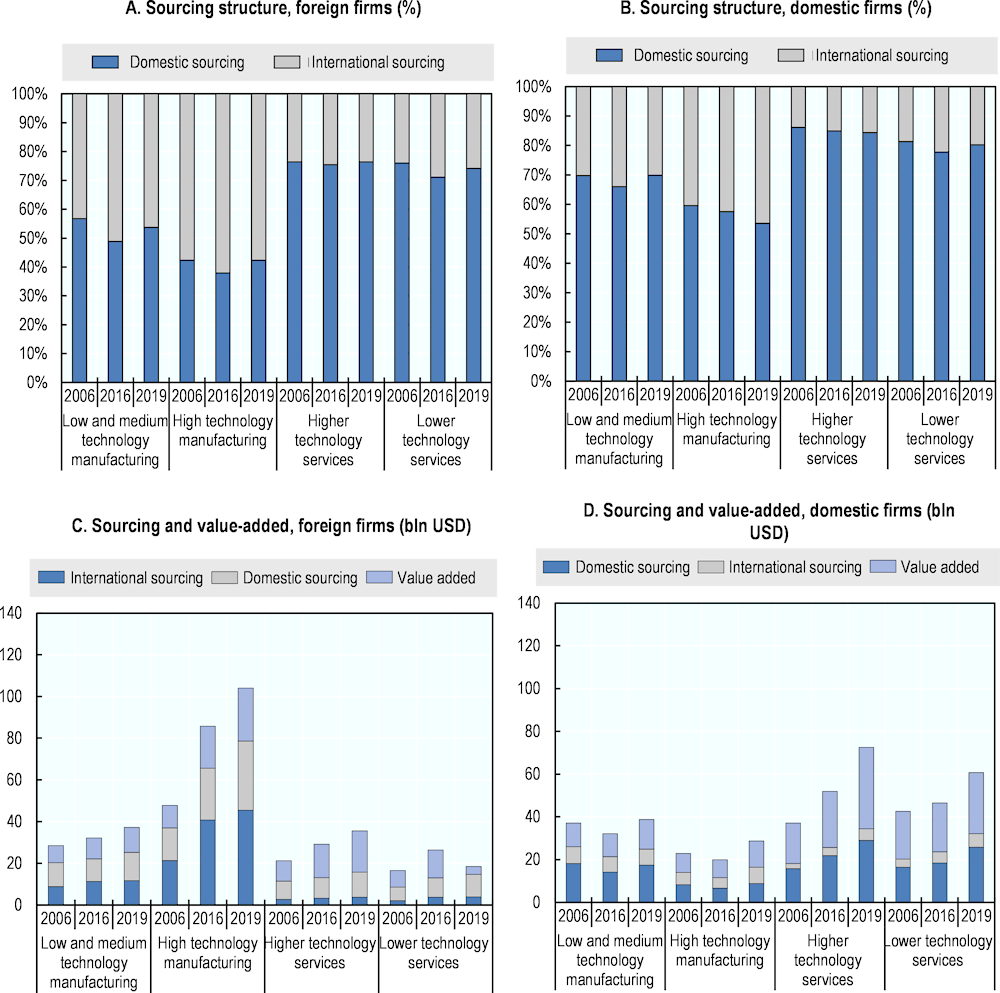

Both foreign and Czech firms rely on domestic – instead of international – sourcing of intermediate inputs in services more than in manufacturing. On average, domestic sourcing accounted for about three quarters of total sourcing by foreign affiliates in services and half of such sourcing in manufacturing in Czechia (Figure 3.4, Panel A). These shares have remained stable over time. This is not surprising given that many services are non-tradable and can be sourced only locally. The share of domestic sourcing is lowest for high-technology manufacturing intermediate inputs, particularly among foreign firms (58% of total sourcing of foreign and 46% of domestic in 2019). However, in monetary terms, domestic sourcing by foreign affiliates is greater in high-technology than in low-technology manufacturing, given the higher overall value of sourcing of foreign affiliates in high-technology than in low-technology-manufacturing in Czechia (Figure 3.4, Panel C). Sourcing from high-technology manufacturing by foreign firms is highest in value when compared with domestic firms. Going forward, it would be beneficial to encourage more local sourcing in Czechia’s high-technology manufacturing, given its technology and knowledge intensity, it has the highest spillover potential (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 3.3. Sourcing of foreign affiliates, by type of sourcing, type of local suppliers and country of foreign affiliates’ location (in % of total sourcing), 2016

Copy link to Figure 3.3. Sourcing of foreign affiliates, by type of sourcing, type of local suppliers and country of foreign affiliates’ location (in % of total sourcing), 2016

Note: Foreign MNEs = foreign affiliates of multinational enterprises; domestic MNEs = domestically owned firms with foreign affiliates abroad; domestic non-MNEs = domestically owned firms with no operations abroad. The OECD benchmark countries used in this report are: Slovak Republic, Portugal, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Germany, and Italy.

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database, www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

Figure 3.4. Sourcing of domestic and foreign firms by sectoral groups in Czechia, 2016

Copy link to Figure 3.4. Sourcing of domestic and foreign firms by sectoral groups in Czechia, 2016

Note: The classification of sectors into the different groups follows the classification outlined earlier in this report (see chapter 2).

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database, www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

3.2.2. Foreign MNEs export a large share of their output or sell it to other foreign MNEs in Czechia

Foreign affiliates of MNEs may not only serve as buyers of intermediate goods and services, but also as suppliers to other companies in the host country (forward linkages). Such relationships may allow local firms access to new, higher-quality, or cheaper intermediate inputs (Criscuolo and Timmis, 2017[5]). In addition, many MNEs, especially in industrial sectors such as machinery, offer training to their customers on the use of their products and provide information on international quality standards (Jindra, 2006[6]). They may also help set the standards for the industry, which in turn can help better diffuse innovation. Firms adopting those international standards can more easily integrate in markets abroad.

In Czechia, a higher share of foreign affiliates’ intermediate output is exported or sold to other foreign affiliates operating in the Czech market compared with peer economies, indicating a lower potential for spillovers through forward linkages. Almost 50% of the output of foreign affiliates is exported compared to nearly 40% among the comparator OECD countries (Figure 3.5, Panel A). The rest of the output of foreign affiliates stays in the domestic economy: 35% is used by the final consumer (41% among OECD peers) and 65% for intermediate consumption by local firms (59% among OECD peers) (Figure 3.6). Therefore, a relatively high share of production of foreign affiliates is used for production of local firms, i.e., feeding back into the domestic supply chains. Foreign affiliates of MNEs are responsible for a large share of that domestic intermediate consumption and this share is much higher than in comparator OECD economies (28% compared to 13%). This reflects an important cluster of foreign MNEs located in Czechia taking advantage of opportunities created by demand of other foreign affiliates, in particular in supply chains related to motor vehicles. These shares are similar to those of the Slovak Republic, which is also highly integrated into the global automotive supply chains (30%) but much higher than other comparator economies.

Figure 3.5. Demand for outputs of foreign affiliates in Czechia and OECD, by type of demand and type of local clients (in % of demand), 2016

Copy link to Figure 3.5. Demand for outputs of foreign affiliates in Czechia and OECD, by type of demand and type of local clients (in % of demand), 2016

Note: The OECD benchmark countries used in this report are: Slovak Republic, Portugal, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Germany, and Italy.

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database, www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

Figure 3.6. Use of output of foreign affiliates by type of demand, type of local buyers and country of foreign affiliates’ location (in %), 2016

Copy link to Figure 3.6. Use of output of foreign affiliates by type of demand, type of local buyers and country of foreign affiliates’ location (in %), 2016

Note: Foreign MNEs = foreign affiliates of multinational enterprises; domestic MNEs = domestically owned firms with foreign affiliates abroad; domestic non-MNEs = domestically owned firms with no operations abroad. The OECD benchmark countries used in this report are: Slovak Republic, Portugal, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Germany, and Italy.

Source: OECD (2019[4]), Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) Database, www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

3.2.3. Cooperation on R&D and innovation between Czech firms and their foreign suppliers and clients is moderate

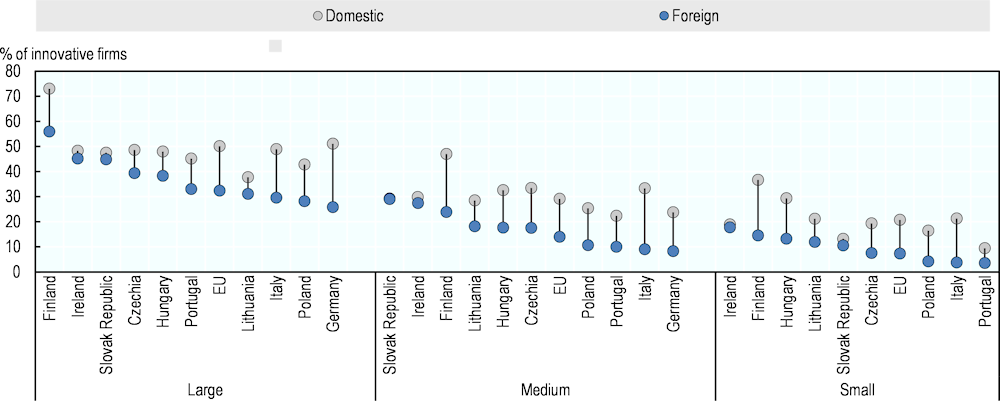

Cooperation on R&D and innovation between domestic firms and both foreign clients and suppliers is moderate in Czechia, indicating that spillovers through knowledge-intensive supply chain linkages may be difficult to materialise (Figure 3.7, Panel A and B). Cooperation with clients and suppliers from the EU/EFTA is most widespread amongst larger firms (11.4% with clients and 15.4% with suppliers) and least common amongst smaller firms (3.6% with clients and 2.9% with suppliers). This could be attributed to larger firms’ stronger innovation performance and capacity to integrate knowledge-intensive supply chains (see Chapter 2). The origin of the foreign client or customer strongly matters. Only a small share of innovative firms in Czechia reports cooperating on R&D and innovation with foreign clients and suppliers from outside the EU or EFTA countries compared to peers, most likely due to the predominance of FDI from Europe in Czechia and the small amount of FDI from other regions of the world.

Figure 3.7. Cooperation with foreign clients on R&D and innovation

Copy link to Figure 3.7. Cooperation with foreign clients on R&D and innovationInnovative enterprises that co-operated on R&D and other innovation activities with clients or customers from the private sector

Note: An enterprise is considered as innovative if during the reference period it introduced successfully a product or process innovation, had ongoing innovation activities, abandoned innovation activities, completed but yet introduced the innovation or was engaged in in-house R&D or R&D contracted out. Non-innovative enterprises had no innovation activity mentioned above whatsoever during the reference period. Small firms = 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized firms = 50 to 249 employees.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

3.3. Strategic partnerships between foreign firms and SMEs in Czechia

Copy link to 3.3. Strategic partnerships between foreign firms and SMEs in CzechiaForeign MNEs and domestic SMEs can establish strategic partnerships around the development of joint R&D and innovation projects, which can create opportunities for technology transfer, especially in high-technology and knowledge‑intensive industries (OECD, 2023[1]). These partnerships can take many forms, including joint ventures, licensing agreements, research collaborations, globalised business networks (i.e. membership-based business organisations, trade associations, stakeholder networks), and R&D and technology alliances. This section provides insights on strengths and opportunities related to strategic partnerships in Czechia.

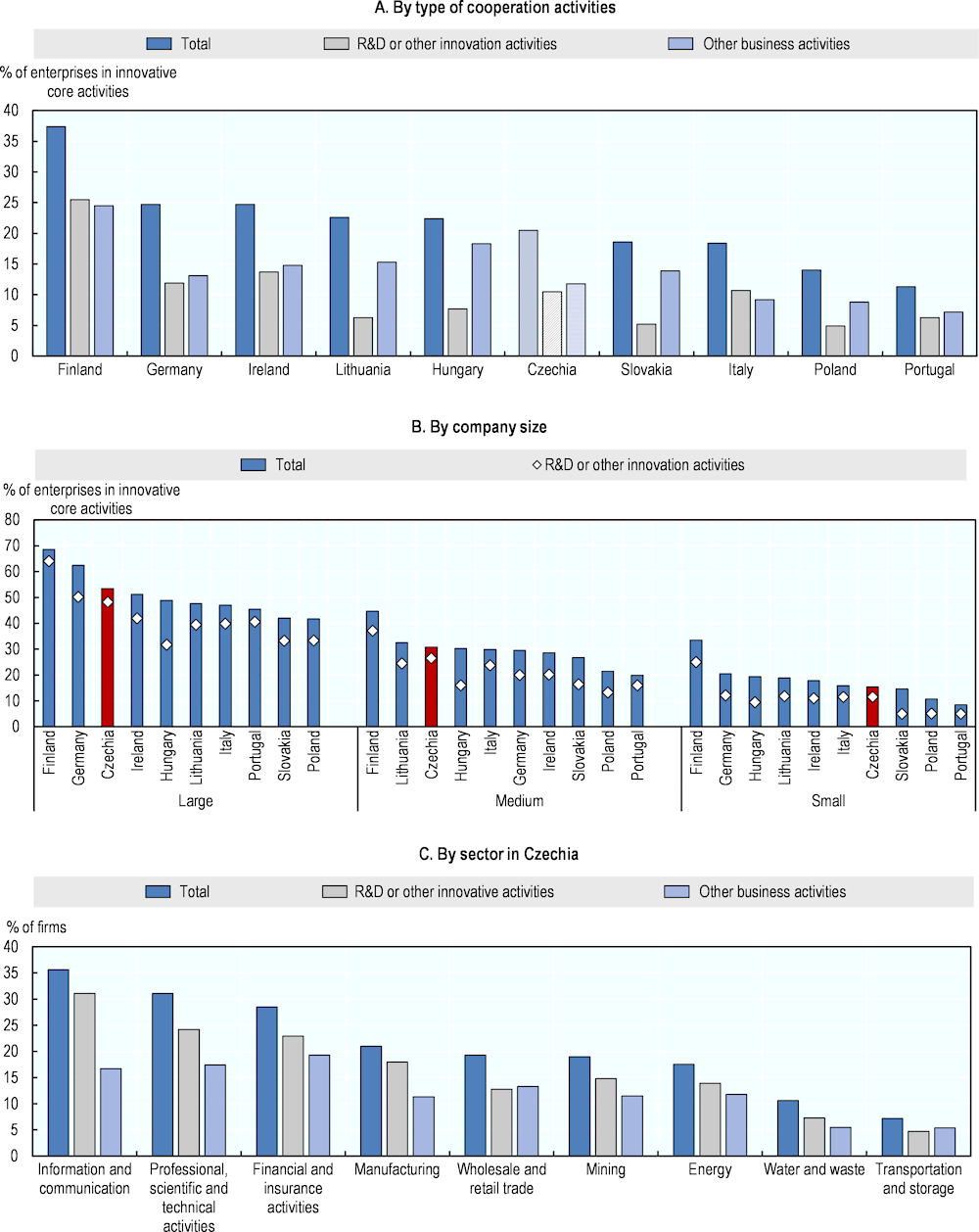

3.3.1. Cooperation through strategic partnerships on R&D and innovation is frequent, but less among small firms

In Czechia, the degree of inter-firm collaborations is moderate, especially among small firms. Approximately 20% of enterprises in Czechia report cooperating through strategic partnerships with other enterprises or organisations, which is similar to the Slovak Republic (19%), much more than in Poland (14%) and Portugal (11%) but significantly less than in top performers such as Finland (37%) or Germany (25%) (Figure 3.8, Panel A). While large and medium-sized firms perform well in comparison to peers in cooperating with other enterprises or organisations, small firms are much less likely to enter such cooperations (Figure 3.8, Panel B). This could be linked to the limited capacities of Czech small firms and their challenges to accessing the necessary knowledge, technology, skills, and finance that inter-firm collaborations often require.

Regarding partnerships involving R&D and innovation specifically, Czech enterprises perform better than their counterparts in peer CEE economies. Although the degree of inter-firm collaboration varies by firm size, the relatively high share of Czech enterprises cooperating on R&D and innovation activities suggests strong potential for technology and innovation spillovers through the facilitation of knowledge exchange. Cooperation with other enterprises is highest in technology- and skills-intensive sectors, including in information and communication (36% of firms) and professional, scientific and technical activities (31% of firms) (Figure 3.8, Panel C). The relatively large amount of cooperation activities in the finance and insurance sector (29% of firms) and somewhat less but still considerable degree of cooperation in manufacturing (21% of firms), which are two of the sectors receiving the largest shares of FDI in Czechia, suggests potentially significant spillovers through strategic partnerships in these sectors. In contrast, inter-firm collaboration is less frequent in the energy, waste and water and transport sectors, which tend to be more capital intensive.

Figure 3.8. Cooperation between businesses on innovation and other activities

Copy link to Figure 3.8. Cooperation between businesses on innovation and other activitiesEnterprises that co-operated on business activities with other enterprises or organisations

Note: An enterprise is considered as innovative if during the reference period it introduced successfully a product or process innovation, had ongoing innovation activities, abandoned innovation activities, completed but yet introduced the innovation or was engaged in in-house R&D or R&D contracted out. Firms report co-operation in R&D, innovation activities, and other business activities. Non-innovative enterprises had no innovation activity mentioned above whatsoever during the reference period. Small firms = 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized firms = 50 to 249 employees.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

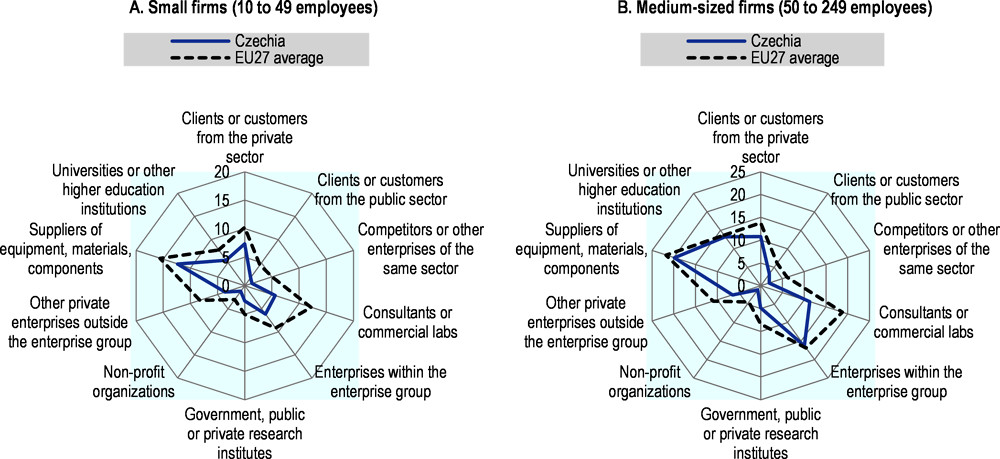

The most common inter-firm collaborations in Czechia are with suppliers (20% of medium-sized and 12% of small innovative firms), with enterprises inside the enterprise group (16% of medium-sized firms and 6% of small innovative firms), with universities (11% of medium-sized and 6% of small innovative firms), and with clients from the private sector (11% of medium-sized and 7% of small innovative firms) (Figure 3.9). Significant disparities, however, continue to persist between Czechia and the EU in terms of cooperation. The most prominent gaps are observed in collaboration with consultants and commercial labs for both small (6% in Czechia and 12% in EU) and medium-sized firms (11% in Czechia and 19% in EU) , as well as cooperation with competitors or other enterprises of the same sector for both small (1% in Czechia and 5% in EU) and medium-sized firms (2% in Czechia and 6% in EU).

Figure 3.9. Enterprises that co-operated on R&D and innovation with other enterprises or organisations, 2020

Copy link to Figure 3.9. Enterprises that co-operated on R&D and innovation with other enterprises or organisations, 2020% of innovative SMEs*, by kind of co-operation partner

Note: *The enterprise is considered as innovative if during the reference period it introduced successfully a product or process innovation, had ongoing innovation activities, abandoned innovation activities, completed but yet introduced the innovation or was engaged in in-house R&D or R&D contracted out. Non-innovative enterprises had no innovation activity mentioned above whatsoever during the reference period. Small firms = 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized firms = 50 to 249 employees.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

Cooperation through strategic partnerships with foreign entities on innovation is less prevalent than with domestic firms, especially among smaller firms, yet more frequent than in the EU. Czech large firms lead in cooperation with foreign enterprises or organisations, with 39% of innovative firms engaging in such collaboration (Figure 3.10). However, this share is lower than the percentage of Czech innovative firms collaborating with domestic entities, which stands at 49%. Among medium-sized firms, 18% in Czechia cooperate with foreign entities on innovation, compared to 14% in the EU, while 34% partake in cooperation with domestic entities. In contrast, only 7.5% of innovative small firms in Czechia cooperate with foreign entities, similar to the EU average of 7.3%, but significantly lower than the share cooperating with domestic entities, which measures at approximately 19%.

Figure 3.10. Cooperation on innovation with foreign and domestic businesses and organisations

Copy link to Figure 3.10. Cooperation on innovation with foreign and domestic businesses and organisationsInnovative enterprises that cooperated on R&D and other innovation activities with domestic and foreign enterprises or organisations (% of innovative enterprises)

Note: An enterprise is considered as innovative if during the reference period it introduced successfully a product or process innovation, had ongoing innovation activities, abandoned innovation activities, completed but yet introduced the innovation or was engaged in in-house R&D or R&D contracted out. Non-innovative enterprises had no innovation activity mentioned above whatsoever during the reference period. Small firms = 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized firms = 50 to 249 employees.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

3.3.2. Czech firms perform well in terms of technology licensing agreements, an indicator for strategic partnerships

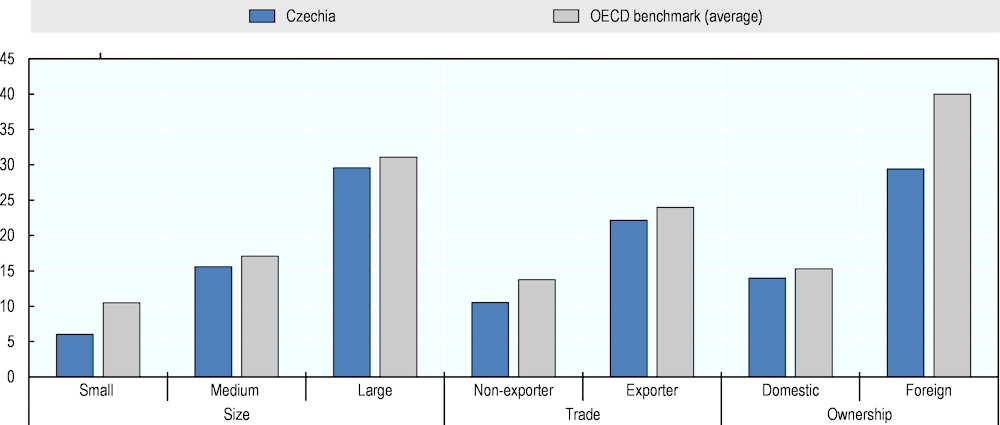

Czech firms in manufacturing enter technology licensing partnerships at a similar rate to firms in comparator economies. The gap is somewhat wider for small firms, however; 6% of them report to have used such agreements relative to 10% across the comparator countries (Figure 3.11). Meanwhile, foreign firms in Czechia appear to engage much less in such forms of partnerships compared to foreign firms in comparator economies (29% compared to 40%). These results could be indicative of potentially fewer opportunities for domestic firms to collaborate with locally established foreign affiliates through such arrangements (while not precluding more frequent use of such partnerships between Czech firms and foreign-owned firms established abroad).

Figure 3.11. Share of firms using foreign technology licensing in the Czech manufacturing sector and that of selected OECD economies, 2019

Copy link to Figure 3.11. Share of firms using foreign technology licensing in the Czech manufacturing sector and that of selected OECD economies, 2019In % of firms

Note: The OECD benchmark countries used in this report are: Slovak Republic, Portugal, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Germany, and Italy. Data for Finland is available for 2020 only and for Germany for 2021.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2022[8]) and based on World Bank Enterprise Surveys, www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys

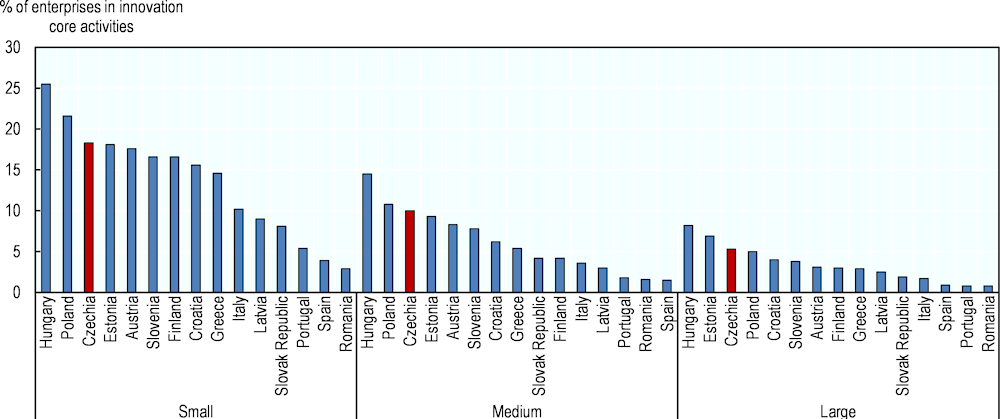

A recent Eurostat survey focusing on the use of technology licensing in selected services sectors suggests that Czech firms employ technology licensing more than most comparators.3 In 2020, 18.3% or large firms, 10% of medium-sized firms and 5.3% of small firms in Czechia, respectively, purchased or licensed intellectual property (IP) rights from other private firms (Figure 3.12). This share is much higher than in the Slovak Republic, for example, as well as Finland and Italy, and is at a level comparable to that of Poland. Engagement in such agreements at a similar, or a higher rate than the average, can be indicative of a potential for FDI-SME spillovers through this mechanism.4

Figure 3.12. Purchasing and licensing intellectual property rights from private businesses

Copy link to Figure 3.12. Purchasing and licensing intellectual property rights from private businessesEnterprises that purchased or licensed in intellectual property rights from private businesses (% of enterprises in innovation core activities, 995/2021)

3.4. Labour mobility between foreign and domestic firms

Copy link to 3.4. Labour mobility between foreign and domestic firmsLabour mobility can be an important source of knowledge spillovers in the context of FDI, notably through the move of MNE workers to local SMEs (OECD, 2023[1]). This can occur through temporary arrangements such as detachments, long-term arrangements such as open-ended contracts, or through the creation of start-ups (i.e., corporate spin-offs) by (former) MNE workers. However, mobility can also occur in the opposite direction, also involving potential for spillovers. This section assesses the potential for spillovers through labour mobility in Czechia.

3.4.1. Job to job mobility has been low historically and is declining in occupations relevant to innovation

Labour mobility is lower in Czechia than in most peer economies, especially in science and technology related occupations. According to Eurostat data on job-to-job mobility focusing on science and technology workers – defined as the movement of individuals between one job and another from one year to the next (excluding flows from unemployment or inactivity) – only 4% of Czech workers transitioned between occupations during 2020 and their mobility has declined over time (Figure 3.13). Only few countries, including the Slovak Republic, have lower job-to-job mobility in those occupations, while some other CEE countries such as Poland and Lithuania have much higher shares (more than double and almost triple than Czechia respectively). Broadening the scope of the analysis to examine worker reallocation rates – defined as the sum of hirings from non-employment or from another job and separations to non-employment over a one-year period range – provides an illustration of the extent of labour market transitions in Czechia. In 2019, Czechia had the lowest worker reallocation rate (15%) among OECD-EU economies, twice the level observed in Finland, Denmark, and Sweden (Causa, Luu and Abendschein, 2021[9]). The contribution of inter-regional mobility to labour mobility is also limited. Approximately 1.4% of Czech workers changing labour market status have also changed region, when this share stands at almost 5% in Sweden, 4% in France and Denmark and 2% in Hungary.

Low levels of labour mobility among highly skilled workers appear to be a long-standing trend in Czechia, suggesting a limited scope for FDI-SME spillovers from that channel. Historical data indicate that changes of occupation were more often related to the young and less-educated workers, including workers in low-skill manual occupations (Vavřinová and Krčková, 2015[10]). The movement of workers between different jobs is predominantly involuntary and often caused by external pressure rather than workers’ efforts to build a career, as illustrated by a particularly sharp, but limited in time, increase in mobility incidence during the recession that followed the 2008 global financial crisis. Anecdotal evidence suggests that patterns of labour mobility in Czechia appear to be shaped by the strictness of the labour market regime (see Chapter 5), regulatory barriers related to specific professions as well as cultural and social perceptions placing priority on job security and stability.

Figure 3.13. Job-to-job mobility of human resources in science and technology, 25-to-64-year-olds, 2010 and 2020

Copy link to Figure 3.13. Job-to-job mobility of human resources in science and technology, 25-to-64-year-olds, 2010 and 2020% of total employed human resources in science and technology

Note: Human resources in science and technology (HRST) describes individuals in science and technology occupations, such as professionals, technicians and associate professionals, as well as those in other occupations who successfully completed a tertiary-level education in science and technology. Job-to-job mobility excludes inflows into the labour market from a situation of unemployment or inactivity. The figure refers to HRST in total NACE (Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community) Rev 2 activities.

Source: Eurostat (2022[11]), Job-to-job mobility of HRST by NACE Rev. 2 activity dataset, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

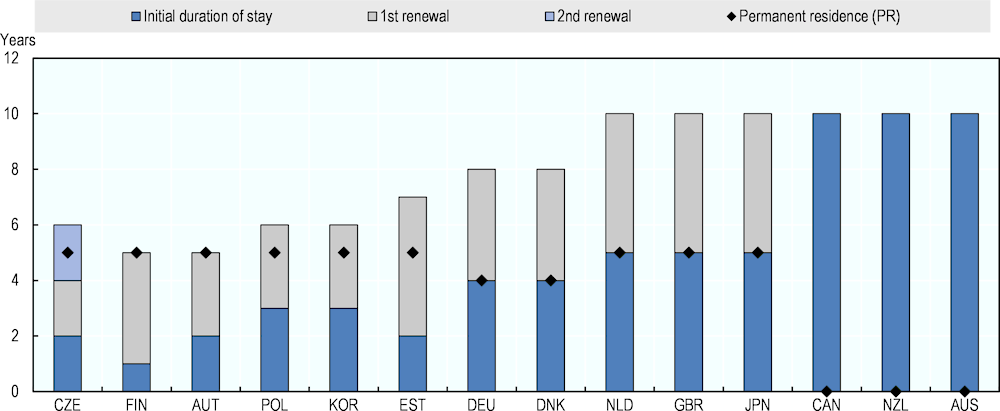

3.4.2. Barriers remain relatively high on inflows of highly skilled foreign workers

While the local labour market is tightly characterised by low job-to-job mobility in certain types of highly skilled personnel, the conditions for mobility of foreign high-skilled workers are also relatively restrictive. For example, conditions in terms of permit duration and labour market mobility in Czechia for highly skilled workers are less favourable than in neighbouring and competing countries (Figure 3.14). The time required to process work permits of non-EU nationals is also significantly longer than certain neighbouring countries like Poland. Highly skilled workers are likely to choose destinations with more favourable conditions and where they can easily relocate with their family. Many countries offer the highest skilled migrants a permanent residence, if not immediately, at least at the end of the first temporary work permit or during the validity of the first renewal. In Czechia, migrants can apply for permanent residency only towards the end of the second temporary work permit and the duration of the initial temporary work permits is shorter than in most comparator countries.

Figure 3.14. Conditions for highly skilled migrant workers in Czechia and selected OECD economies

Copy link to Figure 3.14. Conditions for highly skilled migrant workers in Czechia and selected OECD economiesMaximum permit duration, initial work permits and renewals, and first possible eligibility for permanent residence (years)

Source: OECD based on OECD (2022[12]), Recommendations for a multi-criteria points based migration system for the Czech Republic, https://web-archive.oecd.org/2023-09-23/639970-multicriterial-points-based-system-for-managing-labour-migration-to-the-czech-republic.htm

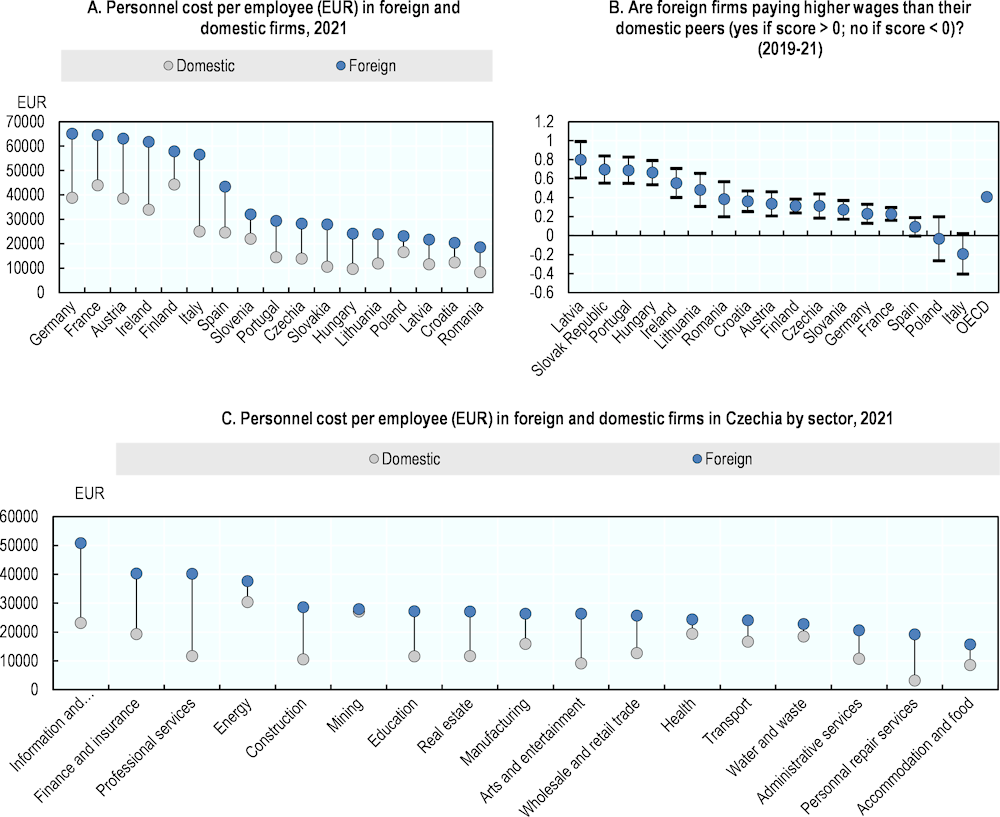

3.4.3. The high wage premia of foreign affiliates may discourage labour mobility towards domestic SMEs

Wages in foreign firms in Czechia are significantly higher than in domestic firms, thereby discouraging labour mobility, and associated productivity and skills spillovers, from foreign to domestic firms. On average, foreign firms’ personnel costs per employee in Czechia – a proxy for wages – are almost twice as high as in domestic firms (Figure 3.15, Panel A), at similar levels as several CEE countries (e.g. Slovak Republic, Hungary, Lithuania) but much lower than most Western European economies (e.g. Germany, France, Austria, Ireland). Evidence from the World Bank Enterprise Survey confirms that wages of manufacturing workers employed by foreign firms in Czechia are higher than in domestic firms and that this difference is highly statistically significant (Figure 3.15, Panel B).

High wages in foreign firms can be attributed to their higher levels of productivity compared to their domestic peers, due to their larger size as well as capital, technological and managerial endowments, which allow them to attract the most talented workers. As discussed in Chapter 2, the productivity gap between small and large as well as foreign and domestic firms in Czechia is bigger than many other OECD economies, and the business population is polarised between a few large very productive firms, which are often foreign-owned, and numerous local SMEs with low productivity. High wage gaps in Czechia may result in increased competition for talent, making it more difficult for Czech SMEs to improve their productivity by recruiting skilled workers, particularly in more remote areas where the labour pool is smaller (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[13]). This effect can be stronger and last longer, in industries facing skills shortages and in locations with limited labour mobility.

Although the potential for direct knowledge and technology transfers to local SMEs through labour mobility is limited in Czechia, reverse spillovers from domestic to foreign firms can contribute to innovation and productivity growth in FDI-intensive industries. This is because foreign firms’ higher wages usually attract the highly skilled workers employed by domestic firms, further strengthening FDI’s skills intensity and direct impact on sectoral and aggregate labour productivity (OECD, 2022[14]). Similarly, in the case of Czechia, positive FDI spillovers on wages in FDI-intensive sectors are more likely to materialise. Studies point to increased wages in domestic firms as a result of the latter’s efforts to retain their skilled workers following FDI’s entry into the same sector or location.

At the sectoral level, wage disparities between foreign and domestic firms in Czechia are most prominent in services industries: namely information and communication, finance and insurance and professional, technical, and scientific services sectors, which are also sectors with the highest shares of cooperation in innovation and other activities amongst enterprises (Figure 3.15, Panel C). Formation of linkages in these sectors cannot be attributed to wage disparities or labour mobility from foreign to domestic firms. Although less significant, wage premia are substantial in the manufacturing sector and in wholesale and retail sectors, which also receive significant amounts of FDI (see Chapter 2).

Figure 3.15. Wages in foreign and domestic firms in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 3.15. Wages in foreign and domestic firms in Czechia

Note: Panel B. Indicator registers a positive value if foreign firms have higher outcomes than domestic firms, and a negative value if foreign firms have lower outcomes, on average. Confidence intervals are reported at the 95% confidence level. If the confidence interval crosses the zero line, the difference of average outcomes of foreign and domestic firms is not statistically significant. The OECD average is based on the latest year, for which data is available, for each country. See methodology in (OECD, 2019[15]).

Source: OECD based on Eurostat, (2022[16]), Foreign Affiliates Statistics (FATS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat, and World Bank, (2023[17]) World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys

3.4.4. FDI’s contribution to the diffusion of skills through training provision is limited

The potential for FDI-SME spillovers through labour mobility also depends on FDI’s skills intensity, as well as training and learning opportunities that SMEs have in the domestic economy, amongst other factors. Foreign investors can increase the supply of skills by providing training to their employees, who could then transfer their knowledge and expertise when they move to domestic firms or set up their own business. Foreign investors can also induce local firms to invest in upskilling in response to rising competitive pressure from their presence in the market, and thus help local entrepreneurs reduce a brain drain towards foreign employers. In the longer term, such initiatives may also result in an increase of the domestic talent pool, with benefits to local entrepreneurship development and may attract further FDI in a virtuous circle.

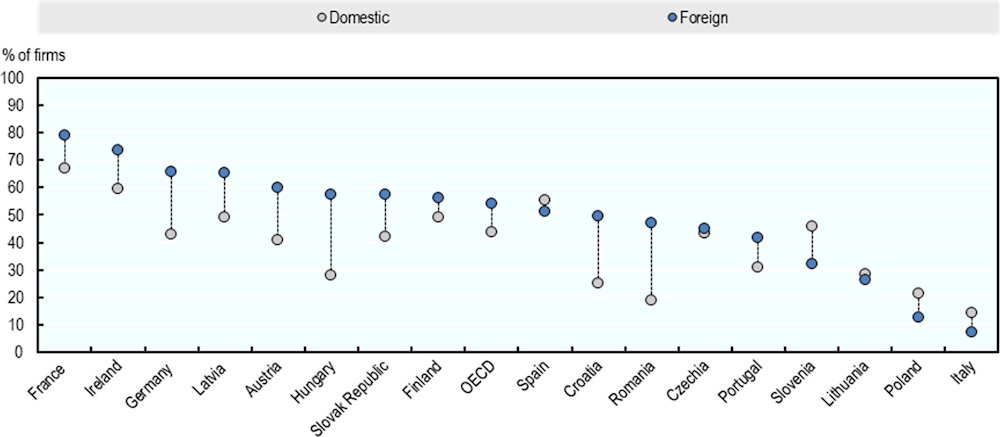

Foreign firms’ provision of on-the-job training to their employees is moderate in Czechia. 45% of foreign firms offer their employees training, approximately the same share as domestic firms (Figure 3.16). Czechia is among the few countries, where foreign firms do not outperform their domestic counterparts in terms of training opportunities and also perform worse than foreign firms in most comparators and in the OECD on average (54%). This could be linked to the concentration of FDI in sectors creating few jobs such as the capital-intensive real estate and finance sectors as well as in low-value added manufacturing linked to assembly and processing, which may not always require highly specialised skills.

Figure 3.16. Training offered by foreign and domestic firms in Czechia and selected EU economies

Copy link to Figure 3.16. Training offered by foreign and domestic firms in Czechia and selected EU economiesProportion of firms offering formal training (%), 2019-2021

Notes: Data on France, Germany, Austria, Spain refer to 2021; on Ireland and Finland to 2020; on Latvia, Hungary, Slovak Republic, Croatia, Romania, Czechia, Portugal, Slovenia, Lithuania, Poland and Italy to 2019.

Source: OECD based on World Bank, (2023[17]) World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys

3.5. Competition and imitation effects of FDI

Copy link to 3.5. Competition and imitation effects of FDIFDI-SME diffusion channels involve market mechanisms related to competition and imitation effects. Competition effects arise when highly efficient MNEs enter the market, impacting domestic companies operating in the same sector or value chain segment, even if not geographically situated in the same region (OECD, 2023[1]). Imitation effects take place at a more local level when domestic firms imitate the practices of foreign MNEs (OECD, 2023[1]; Stančík, 2008[18]). The introduction of new standards by foreign companies may place pressure on domestic companies and thereby generate productivity and innovation spillovers (OECD, 2023[1]; OECD, 2022[8]). This section examines how and to what extent these effects might be at play in Czechia’s FDI and SME sectors.

3.5.1. Cooperation on innovation with competitors is common practice for Czech SMEs, but there is little same sector cooperation, particularly with foreign firms

Frequent collaboration with foreign-owned competitor firms provides significant tacit learning and upgrading opportunities for local SMEs (OECD, 2023[1]; OECD, 2022[8]). New standards set by competitors can further stimulate technical change, the introduction of new products, and the adoption of new processes, all of which can lead to productivity growth (OECD, 2023[1]; OECD, 2022[19]).

In Czechia, cooperation with competitors on innovation is fairly common, suggesting some potential for economy-wide spillovers through imitation or tacit learning (Pavlínek and Žížalová, 2014[20]). Czech enterprises engage with competitors and other enterprises for both product and business process innovation (Figure 3.17, Panel A). Over 24% of medium-sized firms in Czechia collaborated with competitors in product innovation, on par with EU economies like Finland, Ireland, and Germany. Smaller firms perform similarly well, with over 9% of them cooperating in product innovation, surpassing peer countries such as Lithuania and the Slovak Republic. Czechia’s SMEs excel in business process innovation, with over 27% of medium-sized and over 11% of small-sized firms engaging in inter-firm collaborations with their competitors.

Despite the strong potential for tacit learning and knowledge exchange across the wider economy, cooperation within the same sector is notably lower in Czechia than in peer countries, in particular, with foreign firms (Figure 3.17, Panel B). Only 1.2% of Czechia’s small and 1.4% of medium-sized firms engaged in cooperation in R&D and innovation with sector competitors, significantly lower than peer countries such as Finland and the Slovak Republic. The pattern extends to larger firms, suggesting that same-sector inter-firm partnerships with competitors is limited irrespective of firm size. Likewise, when looking at cooperation on innovation with foreign firms only, Czech SMEs and large firms are amongst those with the lowest levels amongst peers (Figure 3.17, Panel C).

Limited same-sector cooperation with foreign firms indicates a relatively lower potential for knowledge spillovers from FDI through imitation or tacit learning. FDI in Czechia has been traditionally concentrated in a few highly specialised sectors (i.e. automotive industry, machinery and equipment) that are dominated by export-oriented foreign MNEs with limited engagement with domestic suppliers and partners. Czech SMEs may find it difficult to maintain their market relevance in these sectors and compete against large incumbent firms. While direct knowledge transfer may be limited, indirect learning through market competition of foreign firm practices could still play a significant role in innovation and growth for Czech SMEs (see next section). Policy interventions could focus on fostering more sector-specific collaborations between local SMEs and foreign firms, potentially diversifying collaboration channels and enhancing direct knowledge spillovers. Supporting SMEs to carve out niche markets or specialise in areas that serve the emerging sourcing and R&D needs of foreign firms could also help further strengthen spillovers through competition/imitation effects.

Figure 3.17. Enterprises partaking in co-operating on innovation (% of innovative enterprises), 2020

Copy link to Figure 3.17. Enterprises partaking in co-operating on innovation (% of innovative enterprises), 2020

Note: The enterprise is considered as innovative if during the reference period it introduced successfully a product or process innovation, had ongoing innovation activities, abandoned innovation activities, completed but yet introduced the innovation or was engaged in in-house R&D or R&D contracted out. Small firms = from 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized = from 50 to 249 employees. Large = 250 employees or more. Micro firms with less than 10 employees are not included.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

3.5.2. A considerable share of firms in Czechia see competition as a barrier to innovate

While high costs, lack of internal finance and lack of qualified employees are the main perceived barriers to innovation in Czech SMEs, high competition is reported to be a barrier of significant importance, particularly by smaller firms. Approximately 18% of small firms, 12% of medium-sized firms and 7% of large firms in Czechia perceive high competition as a barrier of high importance to their innovation performance (Figure 3.18) (against 14%, 12% and 11% respectively in the EU). Those are similar shares of firms as in Portugal and the Slovak Republic but higher than in most comparators such as Finland, Lithuania and Poland. The strong perception of market competition as a barrier to innovation could be linked to challenges faced by Czech SMEs with keeping up with the new and potentially higher quality standards that are imposed by competitors (i.e., management practices, product quality, speed of delivery, etc.) (OECD, 2022[21]) – indicating potentially fewer knowledge spillovers from foreign companies through competition and imitation effects.

The presence of market competition can also signal business dynamism and a well-functioning and competitive market, where new entrants are forced to challenge existing firms and force-out non-productive firms (OECD, 2022[8]). This process of resource reallocation towards more productive businesses is crucial for economic performance by putting pressure on firms to stimulate technical change, introduce new products or adopt new management practices, all of which are possible sources of productivity growth. However, in highly competitive environments, the exit of firms might also point to market distortions that hinder the growth and competitiveness of SMEs. For instance, this is the case when the firms exiting the market are not inefficient incumbents but are instead newer companies that struggled to scale up and engage in knowledge-intensive activities.

Business demography indicators such as rates of market entry and exit, churn rate and business survival, are key in evaluating competition and market conditions in the Czech economy. As described in Chapter 2, Czechia’s economy exhibits limited business dynamism with moderate-low rates of firm births and deaths, and a churn rate below the OECD average, both across the entire business economy and in manufacturing. Czechia also has a high 2-year business survival rate that stood at 71% in 2020, above most peer economies and the EU average (63%). Although these findings may point towards a potentially conducive environment for smaller firms to scale up and maintain or expand their market share, fewer businesses entering and exiting the market may also reflect a risk-averse culture among entrepreneurs and investors, leading to fewer startups and business closures as well as slower innovation since fewer new business ideas are being tested in the market. At the sectoral level, regulatory barriers to entry for new businesses and barriers to exit for unproductive firms could also be at play as highlighted in Chapter 5. Low levels of market competition could therefore be a signal of the poor efficiency of competition/imitation effects for FDI-SME knowledge spillovers in the Czech economy.

Figure 3.18. Share of enterprises who view high competition as a ‘highly important’ barrier to innovation, 2020

Copy link to Figure 3.18. Share of enterprises who view high competition as a ‘highly important’ barrier to innovation, 2020

Note: Small firms = from 10 to 49 employees. Medium-sized = from 50 to 249 employees. Data for Finland was taken from the year 2018.

Source: Eurostat (2020[7]), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat

References

[2] Alfaro-Urena, A., I. Manelici and J. Vasquez (2022), “The Effects of Joining Multinational Supply Chains: New Evidence from Firm-to-Firm Linkages”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 137/3, pp. 1495-1552.

[25] Antràs, P. and Yeaple. Stephen R (2014), “Multinational Firms and the Structure of International Trade”.

[5] Cadestin, C. et al. (2019), “Multinational enterprises in domestic value chains”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 63, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[3] Cadestin, C. et al. (2019), Multinational enterprises in domestic value chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9abfa931-en.

[10] Causa, O., N. Luu and M. Abendschein (2021), Labour market transitions across OECD countries: stylised facts, OECD, https://one.oecd.org/document/ECO/WKP(2021)43/en/pdf.

[6] Criscuolo, C. and J. Timmis (2017), “The Relationship Between Global Value Chains and Productivity”, International Productivity Monitor, Centre for the Study of Living Standards, vol. 32, pages 61-83, Spring.

[17] Eurostat (2022), Foreign Affiliates Statistics (FATS), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[12] Eurostat (2022), Job-to-job mobility of HRST by NACE Rev. 2 activity dataset, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat.

[8] Eurostat (2020), Community Innovation Survey 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 10 January 2024).

[24] Havranek, T. and Z. Irsova (2011), “Estimating vertical spillovers from FDI: Why results vary and what the true effect is”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 86/11.

[7] J., S. (ed.) (2006), The Theoretical Framework: FDI and Technology Transfer, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

[23] Javorcik, B. (2004), “Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages.”, American Economic Review, Vol. 94, pp. 605-627.

[14] Lembcke, A. and L. Wildnerova (2020), “Does FDI benefit incumbent SMEs?: FDI spillovers and competition effects at the local level”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2020/02, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/47763241-en.

[13] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Surveys: Czech Republic 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e392e937-en.

[1] OECD (2023), Policy Toolkit for Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/688bde9a-en.

[15] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ba74100-en.

[20] OECD (2022), Strenghtening FDI and SMEs linkages in Portugal, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[9] OECD (2022), Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in the Slovak Republic.

[22] OECD (2022), Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in the Slovak Republic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/972046f5-en.

[16] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, ., https://www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

[4] OECD (2019), OECD Analytical Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) database, http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm.

[21] Pavlínek, P. and P. Žížalová (2014), Linkages and spillovers in global production networks: firm-level analysis of the Czech automotive industry, https://academic.oup.com/joeg/article/16/2/331/2412424.

[19] Stančík, J. (2008), FDI Spillovers in the Czech Republic: Takeovers vs. Greenfields, https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication14299_en.pdf.

[11] Vavřinová, T. and A. Krčková (2015), “Occupational and Sectoral Mobility in the Czech Republic and its Changes during the Economic Recession”, Statistika Statistics and Economy Journal, Vol. 95/3, pp. 16-30.

[18] World Bank (2023), World Bank Enterprise Surveys, https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/enterprisesurveys.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. Since the seminal study on this topic, there has been a stream of empirical research investigating the degree of backward spillovers (Javorcik, 2004[23]). The results of a meta-study of this literature studying the effects of backward linkages on local firms suggests that they are economically important (Havranek and Irsova, 2011[24]). The newest literature, using granular data on firm-to-firm transactions, also finds important and statistically significant positive results (e.g., (Alfaro-Urena, Manelici and Vasquez, 2022[2]).

← 2. See e.g., Ántras and Yeaple (2014[25]) for a seminal paper in this regard.

← 3. The Eurostat Community Innovation Survey (CIS) 2020 provides information on enterprises that purchased or licensed IP rights from other private business enterprises, by size class. It offers a separate breakdown for firms operating in innovation activities. These are defined to covers the NACE Rev.2 sections B, C, D, E, H, K and NACE Rev. 2 divisions 46, 58, 61, 62, 63 and 71.

← 4. The data reported by Eurostat does include the distinction between such types of firms.