This chapter reviews the mix of policies in place for fostering FDI spillovers on the productivity and innovation of Czech SMEs. It discusses Czechia’s policy framework for FDI attraction, SME development and knowledge-intensive linkages between the two, noting areas for policy reform. It also assesses the regulatory framework affecting the diffusion of knowledge from foreign to domestic firms, focusing on investment and trade openness, competition policy and labour market regulations.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Czechia

5. The policy mix for FDI and SME linkages

Copy link to 5. The policy mix for FDI and SME linkagesAbstract

5.1. Summary of findings and recommendations

Copy link to 5.1. Summary of findings and recommendationsPublic policy plays a pivotal role in enhancing the performance and quality of FDI-SME ecosystems. An integrated approach, combining policy measures in investment, SME development, innovation, and regional development with a supportive regulatory framework, can increase policy effectiveness. Such integration might strengthen the attraction of FDI that enhances productivity and facilitates spillovers to local SMEs. The challenge lies in ensuring that the policy mix is well-aligned with the country's economic structure, policy priorities, and geographical specifics.

Czechia's policy mix for strengthening the synergy between FDI and SMEs focuses more on enhancing domestic SMEs' capacity to absorb the benefits of FDI than on creating new pathways for FDI impact. Czechia has many policies focused on supporting domestic SMEs, compared to a smaller number of policies aimed to assist foreign companies in entering and operating in the Czech business environment. This could imply that while Czechia’s government is working to strengthen its domestic SMEs, there might be room to intensify efforts in attracting and facilitating foreign companies, which could further enhance FDI-SME linkages. However, it’s important to note that organizations like CzechInvest may face challenges in adopting such initiatives because if these objectives are not recognized and supported at the strategic level, it can be difficult to secure the necessary support, funding, or staff for such activities.

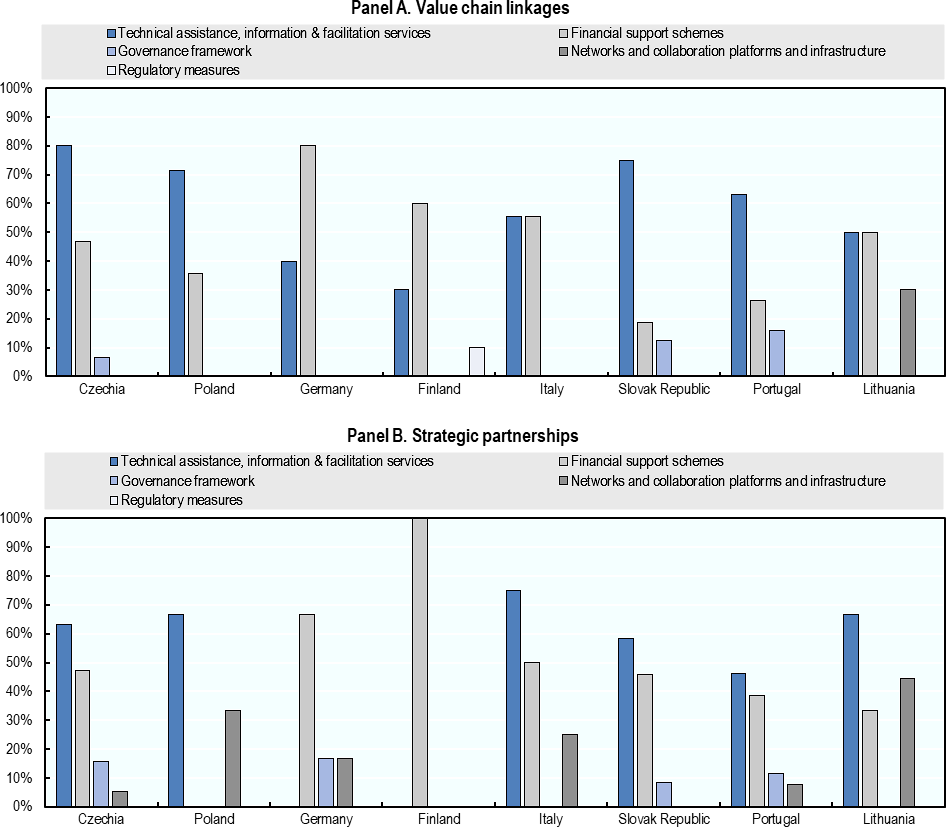

When it comes to strengthening the spillover channels through which FDI affects SMEs (i.e., FDI-SME diffusion channels), Czech policies aim to primarily promote strategic partnerships between SMEs and foreign affiliates (FAs) and to foster value chain. There is a relatively lower emphasis on addressing issues related to labour mobility and competition within the policy mix. However, this analysis does not imply less policy relevance in the areas where less measures are taken, and methodological limitations should be kept in mind in interpretation.

Czechia primarily relies on financial support, technical assistance, and facilitation services to strengthen FDI linkages with domestic SMEs. Financial instruments include grants, loans, tax credits and other forms of direct or indirect funding. Technical assistance, information provision and facilitation services include a wide range of business support measures and services (e.g., consulting, business diagnostic assessments, information, matchmaking and networking, training and skills upgrading, business incubation, etc.). An important factor reflected in the chosen mix of policy instruments lies in Czechia’s emphasis on matchmaking services, platforms, and events, which highlights the importance of networking and collaboration.

Despite the many SME support programmes, SME access to these programmes can be challenging. The delivery of these schemes is fragmented across multiple government agencies, raising barriers to SMEs access to available support. Policy initiatives are predominantly aimed at specific types of firms (e.g., startups), sectors of the economy, or sub-national areas. Initiatives tailored for SMEs also target universities and research centres with the aim to foster business-science linkages and ease the transfer of knowledge to local SMEs. Meanwhile, policies towards private investors, business angels and venture capital funds contribute to improving SMEs’ access to funding. Policy initiatives focusing on specific sectors are also an important part of the policy mix in Czechia. Czechia’s smart specialisation strategy aims to create a long-term competitive advantage by attracting more knowledge-intensive FDI and enhancing the innovation capacity of SMEs in selected priority sectors. The National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) 2021–2027 aims to foster a competitive edge in key sectors like advanced materials, digital and green technologies, and smart cities by focusing on smart specialisation areas with significant potential for knowledge-based innovation and long-term growth.

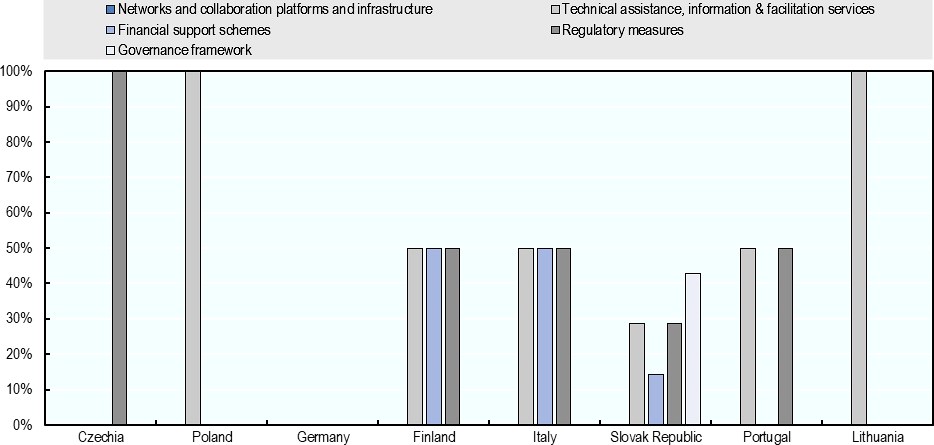

The place-based approach of Czech policies indicates a strategic focus on regional development of economically and socially vulnerable areas. For example, CzechInvest focuses its investment incentives on economically and socially endangered areas according to the Regional Development Strategy of Czechia 2021+ and structurally disadvantaged areas like the Moravia-Silesia, Ústí and Karlovy Vary regions. By doing so, they seek to attract FDI to these areas and foster the growth and development of local SMEs, thereby facilitating the creation of FDI-SME linkages that can contribute to regional economic resilience and prosperity.

There is a strategic emphasis on enhancing the competitiveness and integration of SMEs within different value chains in Czechia. These initiatives aim to attract FDI into sectors where Czech SMEs are active or have growth potential. This can facilitate technology transfer, enhance local capacity, and foster innovation, thereby strengthening the linkages between foreign investors and local SMEs.

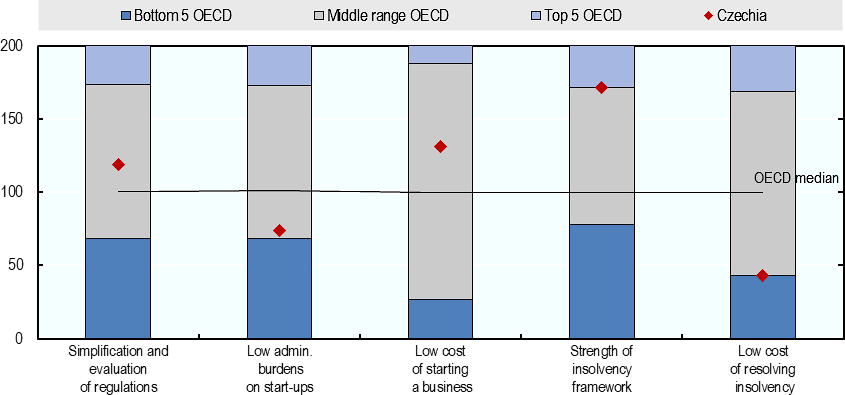

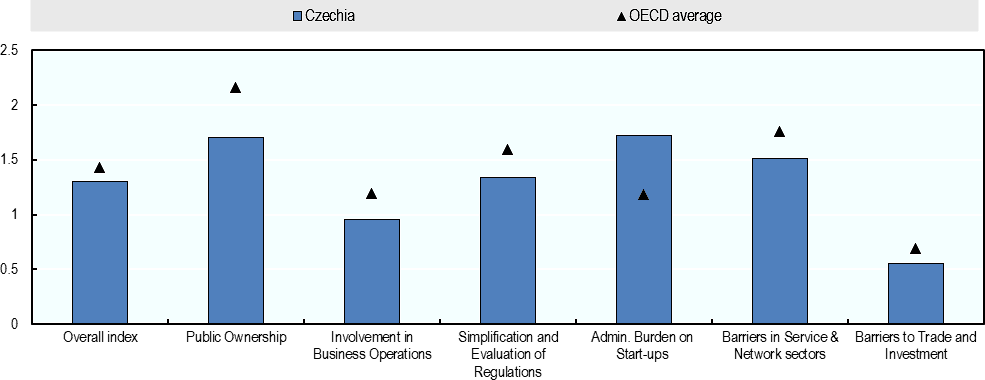

Recent legislative efforts in Czechia have aimed at enhancing the business climate, emphasising the simplification of regulations and reduction of regulatory complexity. Czechia maintains a relatively open economy compared with other OECD countries and this market openness may facilitate the attraction of productivity-enhancing FDI, fostering an environment that is generally welcoming and non-discriminatory toward foreign investors. However, labour market regulations remain an area for improvement, and there are concerns about administrative burdens on start-ups, barriers to competition and regulations surrounding the interaction between policymakers and interest groups. For example, transparency in legislative processes could be enhanced, and concerns persist regarding bureaucratic hurdles, lengthy administrative procedures, and frequent changes to laws and programme rules.

Czechia offers a diverse range of investment incentives, from tax allowances to direct grants, designed to entice both domestic and foreign investors across various sectors, including technology, manufacturing the production of strategic products, and business support services. The set of instruments used is more diversified than in some peer countries. Czechia’s policy framework includes the differentiation of incentives based on the scale of investment, targeted sectors, and regional needs, addressing the varied demands of investment projects and regional economic conditions. For example, CzechInvest’s investment incentive for manufacturing or for technology centres include corporate income tax (CIT) tax relief for up to 10 years, job creation grants as well as training and retraining grants, conditioned to a minimum investment size, certain level of added value, and an exclusive availability in districts with an unemployment rate of at least 7.5%. However, in current economic situation with extremely low unemployment rate these cash grants are almost unobtainable and their conditions should be revised. The investment incentive to produce strategic products is similar with a cash grant of up to 20% of eligible costs conditional to a minimum investment size.

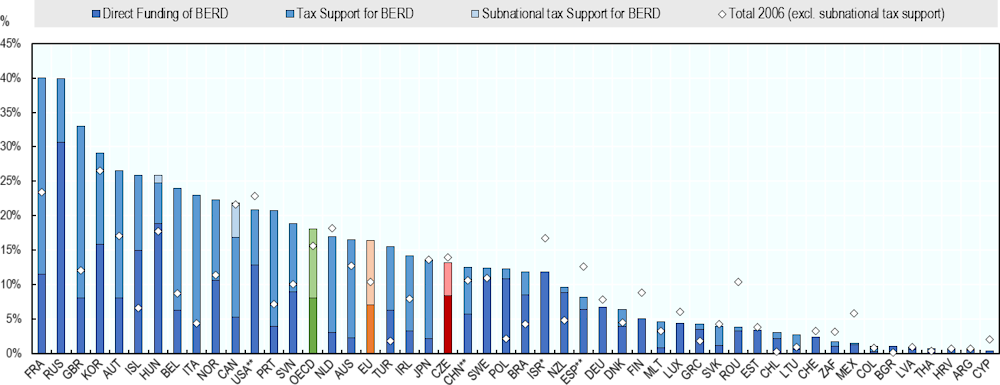

There is room to strengthen public support to business R&D which is currently below the OECD and EU average. The Czech government supports business R&D through comprehensive legislative strategies such as the Innovation Strategy of Czechia 2019–2030, which was endorsed by the government in February 2019. The largest share of public support to business R&D within Czechia is direct, mainly taking the form of grants or loans for R&D and innovation or internationalisation activities; business consulting and training services; or technology acquisition and digitalisation. Czechia has made progress in diversifying its traditional investments in engineering into new fields of research and development (R&D) and innovative technologies. According to the Czech Statistical Office, in 2022, R&D spending rose by 9.3% year-on-year to a record CZK 133.3 billion mainly due to R&D investment by businesses. However, despite the significant potential of some domestic research organisations and infrastructures, the overall quality and performance of public R&D still has room for improvement.

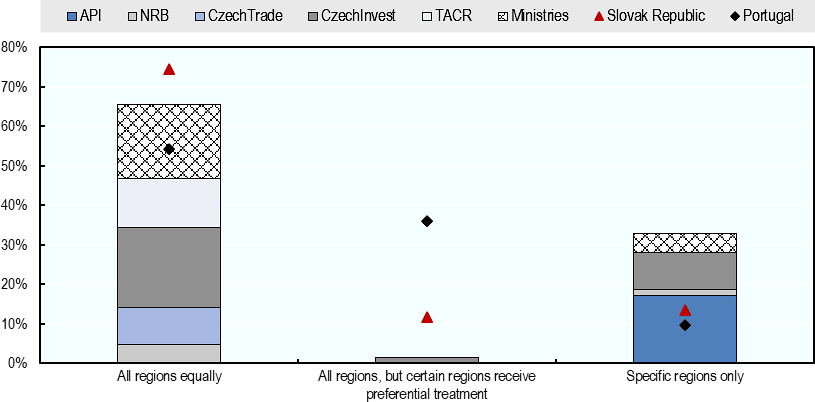

Several Czech policies and programmes adopt a place-based approach, especially in the support provided to business enterprises in the fields of R&D and innovation. This is the case for investment incentives available to domestic and foreign investors, and certain SME R&D and innovation programmes supported by the EU Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF). However, most FDI-SME policies are applied equally across all Czech regions, with few targeting specific regions for preferential treatment. Direct innovation support, such as grants, in Czechia is generally provided from the national level and it is mostly funded from the ESIF and a few national programmes, while indirect support in the form of advisory services (mentroing and coaching, match-making services) is provided regionally through regional innovation centres. There could be more emphasis on innovation and technology diffusion around regional development policies, with a deeper involvement of subnational offices of the main implementing agencies, conditional on the allocation of the additional resources of these subnational offices, and regional innovation agencies. Strengthening the linkages between regional development action plans and the needs of local FDI-SME ecosystems is crucial and could be done, for example, by enchancing mechanism through which regional development agencies interact with business associations and industry representatives at the local level.

In Czechia, the establishment and development of cluster organisations has been actively supported by several institutions. It is a collaborative effort led by several key institutions: the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT), CzechInvest, and the National Cluster Association (NCA). MIT plays a significant role in supporting the expansion of Czech companies abroad and the development of clusters through the Association of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Crafts of Czechia (AMSP CR). CzechInvest supports FDI, develops local Czech companies (SMEs), implements business-development programmes, improves the current business environment, and in cooperation with MIT develops clusters and industrial parks. The NCA brings together entities and individuals with the goal of coordinated and sustainable development of cluster initiatives and cluster policy development in Czechia.

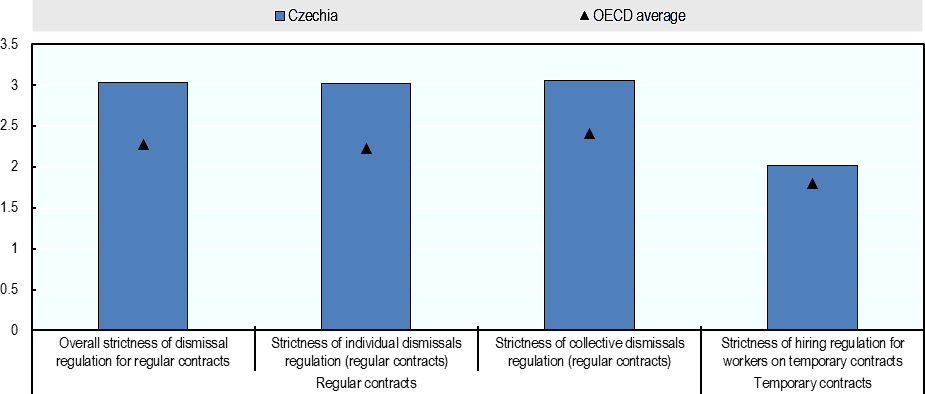

The impact of FDI-SME spillovers resulting from labour mobility hinges on the effectiveness of labour market regulations. The labour market policy in Czechia has focused on removing domestic barriers to labour market participation and addressing labour and skill shortages. According to the 2023 EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages, regulatory measures are the only type of policy instrument deployed in Czechia to facilitate the mobility of skilled workers from foreign affiliates of MNEs to local SMEs. These measures intend to simplify visa application procedures for hiring skilled foreign workers in sectors of strategic importance. Even though regulatory measures are important to set rules and standards, a multi-faceted approach that includes technical assistance, information and facilitation services, financial support schemes, and a strong governance framework can provide a more comprehensive and effective solution to improve labour mobility.

Labour mobility also relies on the presence of policies and programmes that promote the transition of employees from foreign MNEs to local companies. Enhancing collaboration between domestic SMEs and affiliates of foreign MNEs operating locally is a priority objective for Czechia, which mainly does so by supporting value chain linkages and strategic partnerships. In Czechia there are also multiple policies aimed at bridging the skills gap to strengthen FDI-SME linkages such as educational initiatives, incubation programmes, international exposure, and investment incentives. Despite existing policies targeting upskilling the SME population, further support for the diffusion of emerging technologies could be beneficial. More industry-specific training programmes, particularly for sectors crucial to the Czech economy, could be also developed.

Policy recommendations

Copy link to Policy recommendationsIncrease the focus on attracting FDI in high-technology and knowledge-intensive sectors, particularly by shifting investment incentives towards grants and tax relief measures that support productivity growth and involve science-to-business collaboration.

Simplify administrative processes for technology-intensive investments, especially those in collaboration with Czech R&D institutions, to make Czechia more attractive for these investments.

Enhance the capabilities of SMEs to absorb new technologies and innovations by expanding access to technical assistance, capacity-building, and innovation funding schemes.

Reduce administrative burden for SMEs. Transparency in legislative processes could be enhanced and efforts could be made to minimise bureaucratic hurdles, lengthy administrative procedures, and frequent changes to laws and programme rules.

Encourage partnerships between academia, research institutions, and industry to foster innovation and technology transfer, by advocating for a more flexible interpretation of the EU State Aid Framework for R&D & Innovation on the use of R&D infrastructures by business enterprises.

Strengthen the integration and coordination between various policy measures, reducing administrative fragmentation and ensuring harmonisation across different sectors and regions.

Address labour market rigidity and enhance skills development to provide SMEs with access to a skilled workforce, essential for maximising the benefits of FDI. Provide technical assistance and information & facilitation services to businesses and foreign specialists. These services can provide necessary training and skills development, helping workers adapt to new job markets and technologies.

Support the development of industrial clusters through multi-year sectoral action plans involving both public and private sector interventions, aimed at addressing growth bottlenecks.

Pursue a smart specialisation strategy by focusing on sectors where Czechia has or can develop a competitive edge, aligning FDI attraction with national and regional strengths.

Cluster and expand initiatives like Sectoral Database of Suppliers, Czech Business Partner Search, and the Exporter's Directory into one functional program with proper funding and insure the sufficient cooperation and coordination among the institutions involved to promote supplier linkages and partnerships between foreign MNEs and Czech SMEs, particularly in knowledge-intensive value chains.

Improve SMEs' access to finance and technical support, especially for start-ups and smaller firms, by simplifying access to existing financial support schemes and enhancing the technical assistance offered to SMEs.

Implement a more balanced regional development approach by initiating and sustaining a multi-level dialogue between national authorities and regional stakeholders. This can identify and target the types of FDI that align with regional development goals to reduce disparities by promoting FDI in less developed regions, fostering equitable growth across all regions. Ensure policies for attracting knowledge-intensive investment and upgrading SMEs are integrated into regional and local development strategies, promoting a place-based approach to investment and innovation.

5.2. Overall orientation and design of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia

Copy link to 5.2. Overall orientation and design of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia5.2.1. Czechia has a strong policy focus on improving SME absorptive capacity…

The policy mix in Czechia prioritises preparing domestic SMEs to absorb the benefits of FDI (enabling conditions) rather than focusing on creating new pathways for FDI impact (diffusion channels). The overall orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix refers to the broad directions that policy action takes and reflects on the strategic objectives pursued in the policy areas under study (i.e. investment, SME and entrepreneurship, innovation and regional development).

Enabling conditions for FDI-SME linkages include SME performance, productivity enhancing FDI, and economic geography factors. Policies for improving SME performance include measures to strengthen their access to and use of strategic resources, namely finance, skills and innovation assets. Policies for enhancing the impact of international investment on local productivity and innovation aim to attract or retain FDI with potential to create linkages with and spillovers to the host economy, such as greenfield and technology or innovation intensive investment. Other enabling conditions are related to economic geography (OECD, 2023[1]).

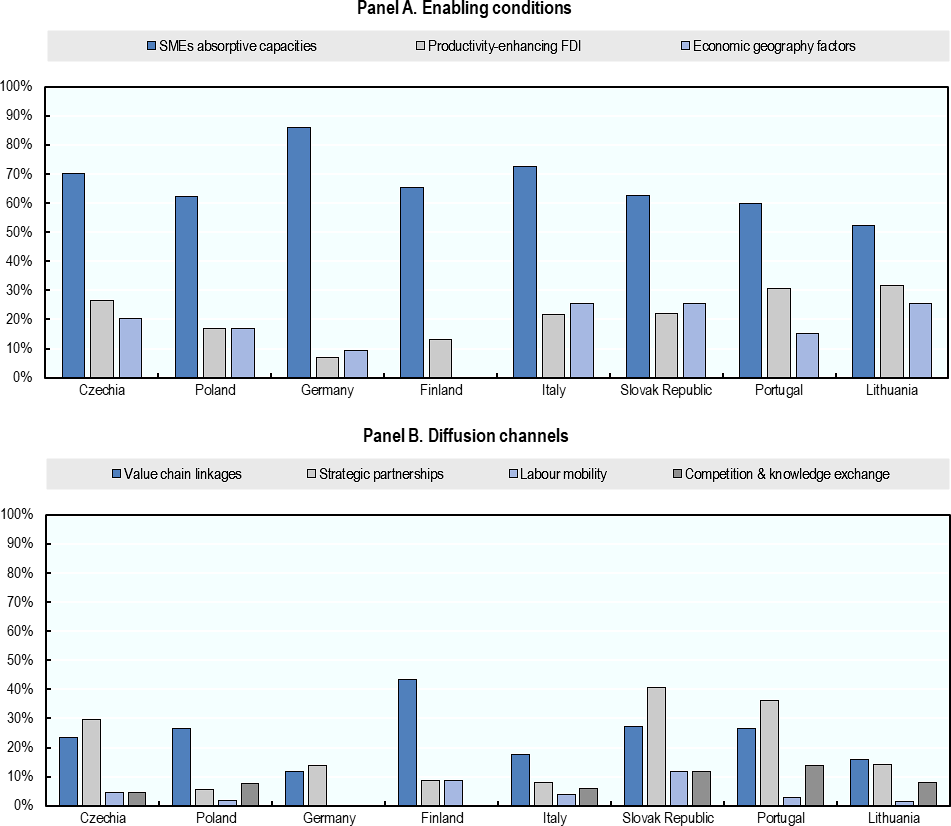

The FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia predominantly focuses on improving the absorptive capacity of domestic SMEs. In the policy mapping conducted by the OECD in 2023, approximately 70% of the policy measures are directed towards enhancing SME performance, 27% focus on productivity enhancing FDIs, and 20% on economic geography factors (total above 100% as some policies might have multiple targets (Figure 5.1, Panel A). This strategic focus indicates a commitment to strengthening the competitiveness and capabilities of local businesses.

Regional inequalities may affect FDI-SME linkages and the performance of FDI-SME ecosystems. Less developed regions are less attractive to foreign investors, and the capacity of the local businesses to capture innovation spillovers is more constrained. Policies addressing economic geography factors aim to promote agglomeration and industrial clustering (OECD, 2023[1]).

5.2.2. ... and less on strengthening the ways foreign investment reaches the SMEs themselves.

When it comes to developing FDI-SME diffusion channels, Czech policies aim to promote strategic partnerships between SMEs and foreign affiliates (FAs) and the strengthening of value chain linkages. In Czechia, 30% of the measures intend to develop strategic partnerships between SMEs and foreign affiliates (FAs) and 23% aim to strengthen value chain linkages (Figure 5.1, Panel B). This points to the importance of these strategic objectives in the policy mix.

There is a relatively lower emphasis on addressing issues related to labour mobility and competition within the policy mix. Only a small number of measures address the issues of labour mobility and competition (accounting for 5% of mapped policies each) (Figure 5.1, Panel B). However, this analysis does not imply less policy relevance in the areas where less measures are taken, and methodological limitations should be kept in mind in interpretation (Box 5.1). Considering the number of policy initiatives that target these policy objectives is only a partial measure of policy focus in a given area. One policy could rely on more resources (e.g. higher budget) for its implementation, and therefore have greater impact, while several policies in another case could be underfunded and not sufficiently effective to achieve the pursued outcomes. For this reason, the policy mix analysis conducted in the following sections takes into account other aspects relating to policy design and implementation, including the sectoral and value chain targeting of implemented measures, the uptake of public support schemes, the number of beneficiaries, the quality of the regulatory environment, and the type of policy instruments used to achieve specific policy objectives, amongst others. The density of the policy mix could also reflect the multidimensional dynamics at play in creating the framework conditions for FDI-SME spillovers, and the need to address this complexity through a broader range of measures. The mobility of workers and the quality of competition in domestic markets largely depend on the broader regulatory environment, i.e. laws and regulations affecting the labour and product markets respectively, and less so on targeted FDI-SME policies and programmes.

When compared to peer EU countries, the Czech policy mix exhibits a greater emphasis on attracting productivity-enhancing FDI and strategic partnerships. Enhancing the performance of SMEs is a top priority across all benchmarking countries, particularly in Germany and Italy. But, in Czechia attracting productivity‑enhancing FDI receives more attention (27%) than, for example, in Finland (13%) or in Germany (7%). The same applies to strategic partnerships, supported by a higher share of policies in Czechia (30%) than in most benchmarking countries, except for the Slovak Republic (41%) and Portugal (36%) (Figure 5.1). This may reflect the strategic choice of the Czech government to boost the country’s transition to a knowledge-based economy by attracting more knowledge-intensive investment from abroad and promoting R&D and technology collaboration between businesses, universities, and research institutions.

The variations in policy priorities can be explained by a combination of factors. In addition to the policy strategy for promoting efficient FDI-SME ecosystems, a number of factors can explain these variations, including country-specific characteristics, national industrial structure and specialisation, the degree of regional inequality, and the geographical distribution of business and investment activities across the territory (OECD, 2023[1]). For example, the comparatively stronger focus on enhancing the economic geography factors of investment attraction and SME performance that is observed in peer countries like Slovakia, Italy and Lithuania (25%) compared to Czechia (20%) (Figure 5.1), might reflect the broader regional development divide observed in those countries and the higher importance of bridging it in their overall FDI-SME policy agenda.

Figure 5.1. Orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia and benchmarking countries

Copy link to Figure 5.1. Orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in Czechia and benchmarking countries% of mapped policy measures

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives in place. Total may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Box 5.1. Mapping the FDI-SME policy mix: methodological considerations and challenges

Copy link to Box 5.1. Mapping the FDI-SME policy mix: methodological considerations and challengesThe policy mix concept refers to the set of policy rationales, arrangements and instruments implemented to deliver one or several policy goals, as well as the interactions that can possibly take place between these elements. In the context of knowledge and technology diffusion from FDI to domestic SMEs, these policies often span multiple institutions and policy domains such as innovation, investment, entrepreneurship, science and technology, and regional development. These policies operate within intricate "policy systems," supporting various channels through which FDI spillovers occur, such as value chain relationships, labor mobility, competition, and imitation. Moreover, they also influence enabling factors such as FDI characteristics, SME absorptive capacity, and economic geography. (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[2]).

This chapter largely builds on a mapping of the policy mix supporting FDI-SME ecosystems in EU countries, conducted as part of a multi-year project jointly undertaken by the OECD and the European Commission (EC) in 2019. In this research, a comprehensive mapping of institutional environments, governance frameworks, and policy initiatives related to FDI, and SMEs was conducted. The process involved utilizing keywords, concept searches, and text analysis to identify national and subnational institutions, categorize EU Member States based on institutional complexity, and understand the roles of different institutions (OECD, 2021[3]).

Official sources such as national strategies, action plans, and relevant ministry websites, along with OECD and EU reports, provided policy information on FDI-SME initiatives. Data collection occurred at both national and institutional levels through desk research and an online survey. This research builds upon previous OECD efforts, drawing on methodologies from projects like the “OECD Surveys of Investment Promotion Agencies” and the EC/OECD project on “Unleashing SME potential to scale up”.

Typically, a first challenge in policy mapping consists in defining the scope and identifying the relevant initiatives and policy mix components under analysis. How the exercise is designed can determine its outputs about the strategic orientations of the mix, its instrumentalisation, its governance, and shifts over time. Potential distortions are higher when the number of measures identified are small. In addition, the number of initiatives in place can be highly variable across countries, depending on the size of the country and the capacity of its public administration, the intensity of the policy interest given, or the maturity of the policy field and the likelihood of initiatives having piled up over time.

A second challenge for policy mapping and impact assessment arises from the question of quantifying policy initiatives. A simple counting presents the advantage to be easy to understand – albeit not necessarily easy to implement or to interpret – and the counting could be discriminated by policy area, instrument, target population, sectors, etc. Policy initiatives could also be accounted in terms of input (e.g. public budget allocated), output (e.g. new strategic partnerships between foreign affiliates and local SMEs) and outcome (e.g. net job creation). The lack of data at disaggregated level, i.e., at the level of the policy initiative, is a clear limitation in this statistical approach. The number of FDI-SME policy initiatives in place is therefore a partial measure of the intensity of a country’s effort in each area, and other parameters matter.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[2]; OECD, 2023[1]; OECD, 2022[4])

5.2.3. Czechia mostly supports its FDI-SME ecosystem through the provision of financial incentives and technical assistance.

Public action to foster FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs is delivered through a broad set of policy instruments. These are defined as identifiable techniques for public action and the means for achieving the goals they are designed for (Lemarchand, 2016[5]), and spread from technical (non-financial) to financial support, from networking assistance to infrastructure and platform facilities, from regulatory easing to new governance frameworks such as national strategies or plans (OECD, 2023[1]). Box 5.2 provides an overview of the policy instruments typology adopted throughout this chapter.

Box 5.2. The FDI-SME policy mix: a typology of policy instruments

Copy link to Box 5.2. The FDI-SME policy mix: a typology of policy instrumentsGovernments have a diverse set of policy instruments at their disposal to support FDI-SME ecosystems. A policy initiative can make simultaneous use or various policy instruments, using them in complementary and mutually reinforcing ways to achieve the desired strategic objective.

Based on the type of instrument used, policies can be classified into:

Network and collaboration platforms and infrastructure, which refers to platforms, facilities and infrastructures that enable spatial and network-related knowledge diffusion.

Technical assistance, information, and facilitation services, which aim to encourage the uptake of knowledge and facilitate interactions between foreign and domestic firms (e.g., matchmaking services and networking events).

Financial support schemes, in direct (e.g., grants, loans) or indirect forms (e.g. tax relief) to encourage (or discourage) certain types of business activities (e.g. investment tax incentives, R&D vouchers, wage subsidies for skilled workers).

Regulatory measures, which define the framework within which foreign and domestic firms operate and often use legal rules to encourage or discourage different types of business activities (e.g., lighter administrative and licensing regimes for certain types of investments, local content requirements for foreign firms and labour mobility incentives).

Governance frameworks, such as national strategies and action plans that lay out policy priorities and define the framework within which policy action on FDI, SMEs and innovation is organised. Some guiding instruments have co-ordination functions and ensure overarching policy governance (e.g., national strategies or action plans)

Table 5.1 provides an overview of the main FDI-SME policy instruments, illustrated by selected examples. Based on this typology, the present Chapter presents key findings on the instrumentalisation of the FDI‑SME policy mix in Czechia and the selected benchmarking countries.

Table 5.1. Policy instruments to strengthen the performance of FDI-SME ecosystems

Copy link to Table 5.1. Policy instruments to strengthen the performance of FDI-SME ecosystems|

Instruments typology |

Examples |

|---|---|

|

Network and collaboration platforms and infrastructure |

Special Economic Zones, technology centres and science parks, industrial parks, cluster policies |

|

Technical assistance, information and facilitation services |

Local supplier databases, business diagnostic tools, FDI site selection services, work placement or employee exchange programmes, supplier development programmes, business support centres, knowledge exchange and demonstration events, matchmaking services, platforms and events, business consulting and skills upgrading programmes |

|

Financial support schemes |

Financial incentives for intellectual property protection, financial incentives for B2B and S2B partnerships, wage subsidies for skilled workers, tax incentives for productivity-enhancing investment, tax incentives for R&D and innovation activities, equity financing, grants/loans for business consulting and training services, grants/loans for technology acquisition and digital transformation, grants/loans for internationalisation activities, grants/loans for R&D and innovation activities, innovation and internationalisation vouchers, other financial support schemes |

|

Regulatory measures |

Residence-by-investment schemes, labour mobility regulation and incentives, regulatory and administrative easing for FDI Special investment status, other regulatory standards, and incentives |

|

Governance frameworks |

Strategies/action plans on SMEs/entrepreneurship, strategies/action plans on innovation, strategies/action plans on regional development, strategies/action plans on FDI/internationalisation, other strategies with FDI & SME provisions |

Note: This typology of policy instruments reflects the framework developed in the OECD FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit (OECD, 2022[6]) and the OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook (OECD, 2021[7]; OECD, 2023[8]; OECD, 2019[9]). It was used in the country assessments of FDI-SMEs linkages in Portugal (OECD, 2022[10]) and the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2022[4]). It will also be used in the SME&E data lake knowledge infrastructure. This typology is aligned with converging classifications of policy instruments formerly used in environmental and innovation policy literature ( (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[2])) ( (Rogge and K., 2016[11]); (Edler, 2013[12]); (Borras and Edquist, 2013[13]); (Flanagan, 2011[14]); (OECD, 2007[15]); (OECD, 2010[16]); (Eliadis, 2005[17])]; (Smits, 2004[18]); (Bemelmans-Videc and Rist, 1998[19])).

Source: (OECD, 2023[1]), OECD elaboration based on analytical framework and literature review.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[2]; OECD, 2023[1]; OECD, 2022[4])

The mix of policy instruments used and the way they are combined reflect the different strategic objectives that a country may seek to achieve, as well as the many pathways to achieving policy outcomes. Instruments are often very specific to the objectives they serve. The selection of instruments also reflects national policy styles and some policy legacy (Borras and Edquist, 2013[13]). For instance, some instruments, particularly the financial ones, can dominate others for no other reason than being important in the past, having attracted around them vested interests that protect their position.

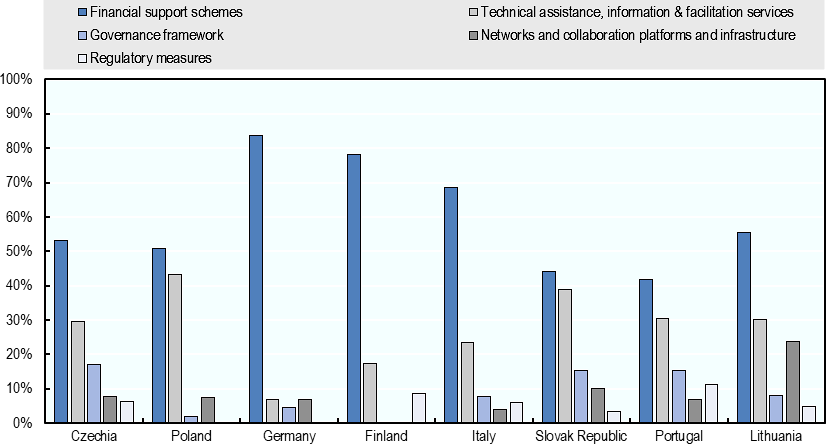

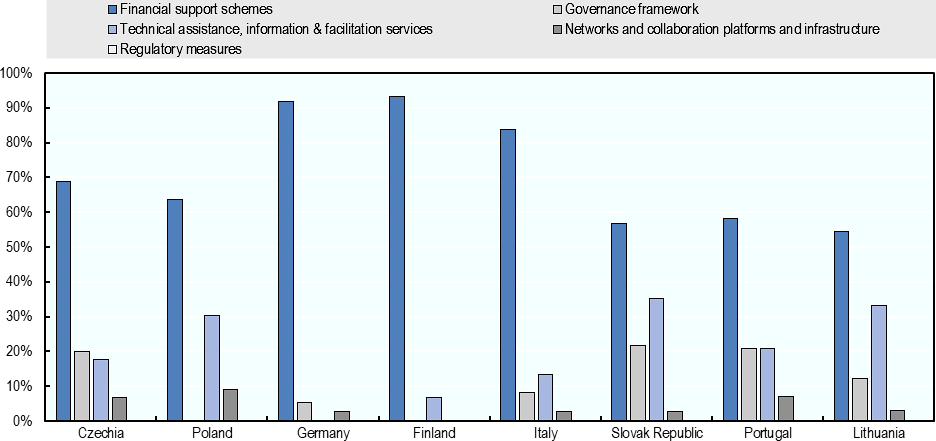

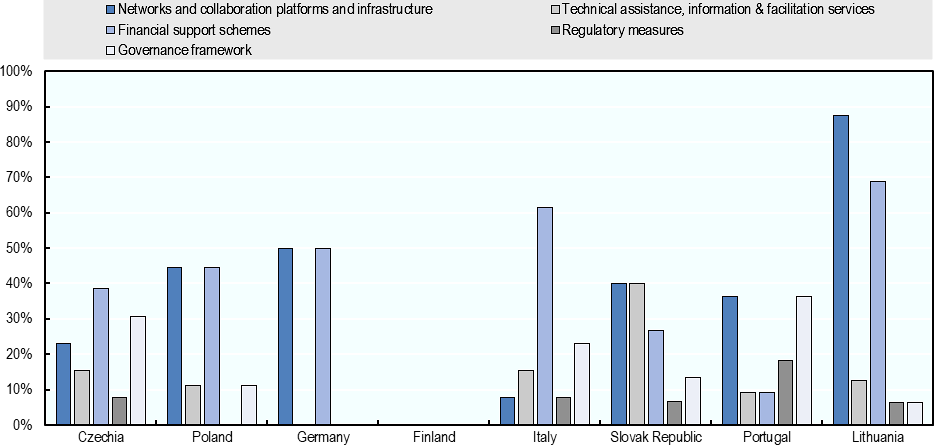

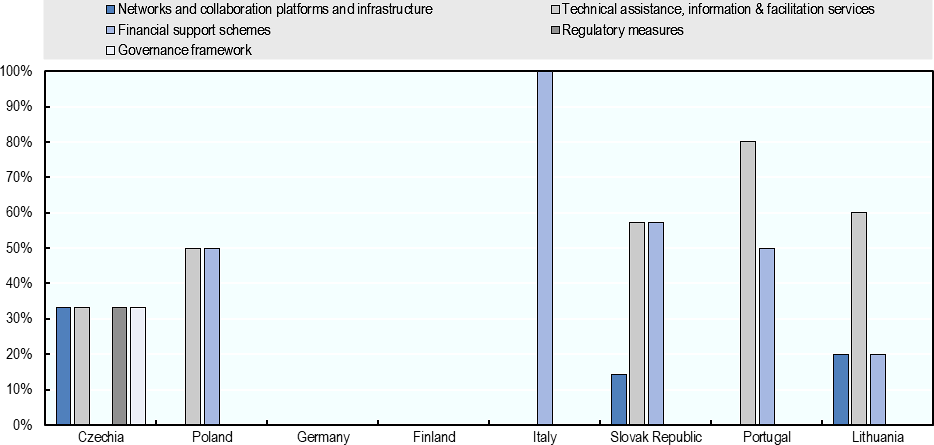

Czechia primarily relies on financial support and technical assistance and facilitation services to strengthen FDI linkages with domestic SMEs. Like the selected EU benchmarking countries, Czechia mainly uses financial support (53%) and technical assistance and facilitation services (30%) to strengthen FDI linkages with domestic SMEs (Figure 5.2). Financial instruments include grants, loans, tax credits and other forms of direct or indirect funding. Technical assistance, information provision and facilitation services include a wide range of business support measures and services (e.g., consulting, diagnostic, information, matchmaking and networking, training and skills upgrading, incubation, etc.).

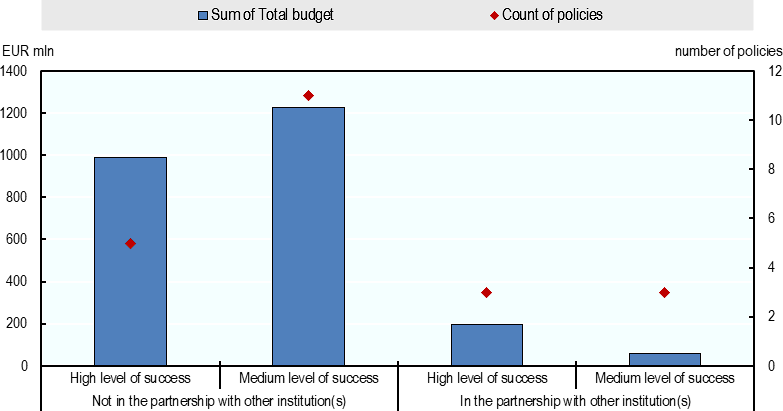

In Czechia, although a comprehensive set of funding programmes is available to support the absorptive capacities of domestic SMEs, there are challenges for SMEs to access them. As discussed in Chapter 4, the delivery of these schemes is relatively fragmented across multiple government agencies raising barriers to SMEs access to available support. The effectiveness of available financial scheme’s may be influenced by their volume and by the number of institutions involved in implementation, and the degree of policy fragmentation. In the Slovak Republic, for example, although the number of financial support schemes for businesses is large, their volume is relatively low, due to the limited resources allocated through the state budget and challenges in the absorption of EU funds (OECD, 2022[4]). In Czechia, among 30 mapped policies to support the absorptive capacities of domestic SMEs through financial support schemes, 22 of them have data on budget and level of success. Figure 5.3 illustrates that most initiatives (73%) are not the product of cooperation between institutions and their budgets varies from EUR 280 thousand to EUR 400 million per initiative. The high administrative burden for SMEs, alongside the limited scope of their support and the small number of beneficiaries, has led to a moderate success rate, with 69% achieving a medium level of success and 31% reaching a high level of success in these policies. Financial schemes, which are managed in partnership with multiple institutions, typically have a smaller funding range (between EUR 19 to 150 million) and are less prevalent, constituting only 27% of such policies.

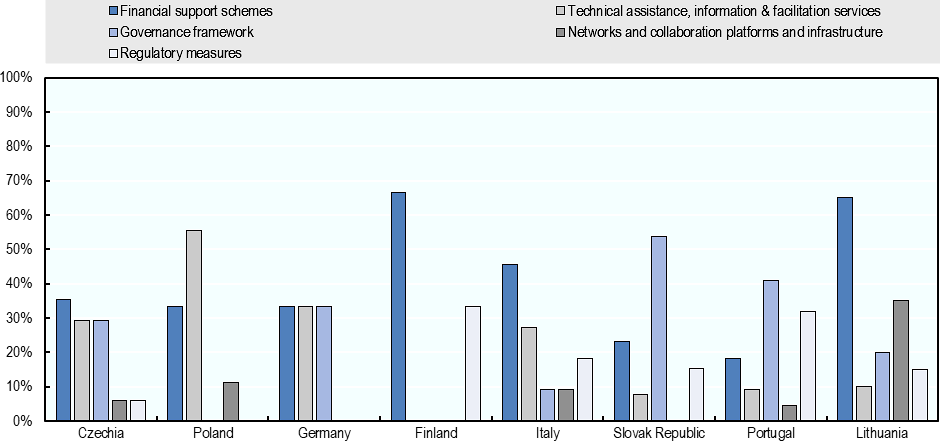

Figure 5.2. Policy instruments used in Czechia and benchmarking countries

Copy link to Figure 5.2. Policy instruments used in Czechia and benchmarking countriesIn % on mapped policy measures

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives in place. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Figure 5.3. Success of the financial support initiatives for strengthening the absorptive capacities of Czech SMEs implemented in/without partnership with other institutions

Copy link to Figure 5.3. Success of the financial support initiatives for strengthening the absorptive capacities of Czech SMEs implemented in/without partnership with other institutions

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

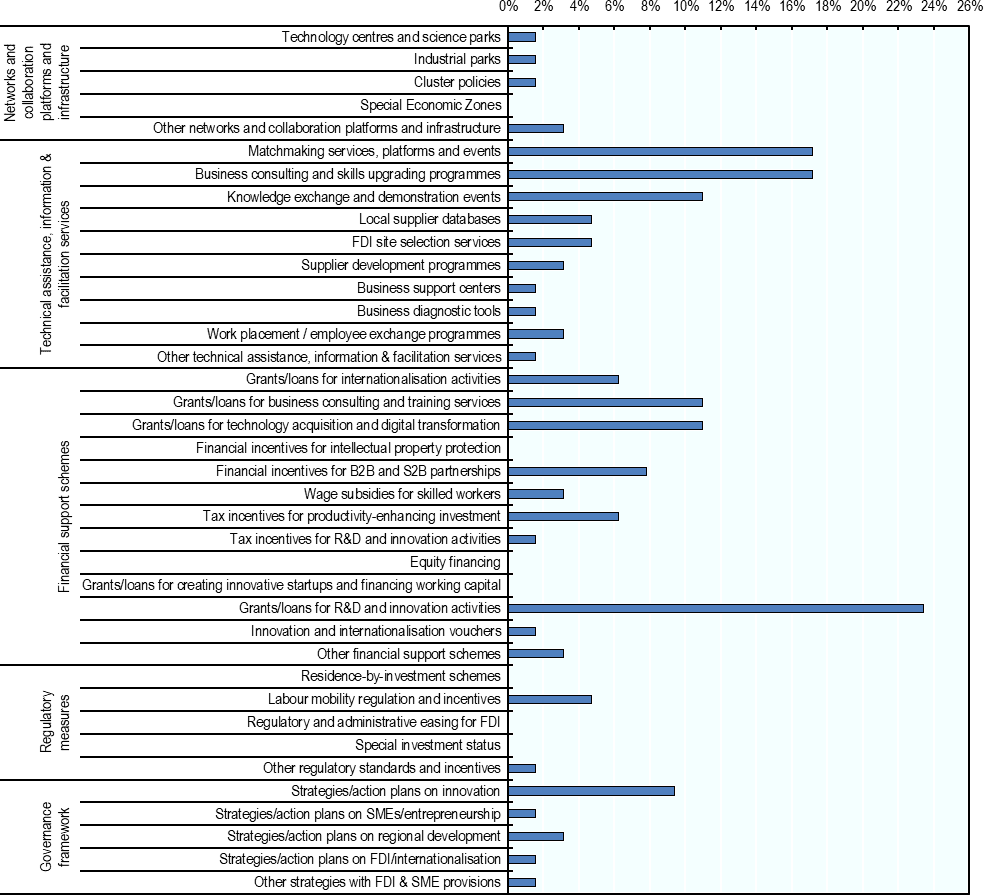

An important factor reflected in the chosen mix of policy instruments lies in Czechia’s emphasis on technical assistance and facilitation services (Figure 5.4). This category includes crucial instruments like "matchmaking services, platforms and events", "business consulting and skills upgrading programmes", and "knowledge exchange and demonstration events." This underscores the importance of creating a supportive environment and providing resources for SMEs to enhance their capabilities and collaborations. The emphasis on "matchmaking services, platforms and events" under technical assistance highlights the importance of networking and collaboration. Additionally, the inclusion of "business consulting and skills upgrading programmes" signifies a commitment to enhancing the skills and capabilities of SMEs, aligning with broader economic development goals.

Figure 5.4. Main typologies of policy instruments used in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 5.4. Main typologies of policy instruments used in Czechia% of mapped policy measures

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives in place. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Policy instruments focus significantly on R&D and innovation. Within the "financial support services" typology, there is a notable focus on promoting Research and Development (R&D) and innovation activities. Specifically, "Grants/loans for R&D and innovation activities" constitute a substantial 24% of the total national initiatives (Figure 5.4). This reflects a strategic policy orientation towards fostering innovation and technological advancement within the SME sector, indicating a commitment to enhancing competitiveness through knowledge-intensive activities.

5.2.4. Most Czech FDI-SME policies focus on certain groups or areas, potentially benefiting SMEs but risking economic imbalances

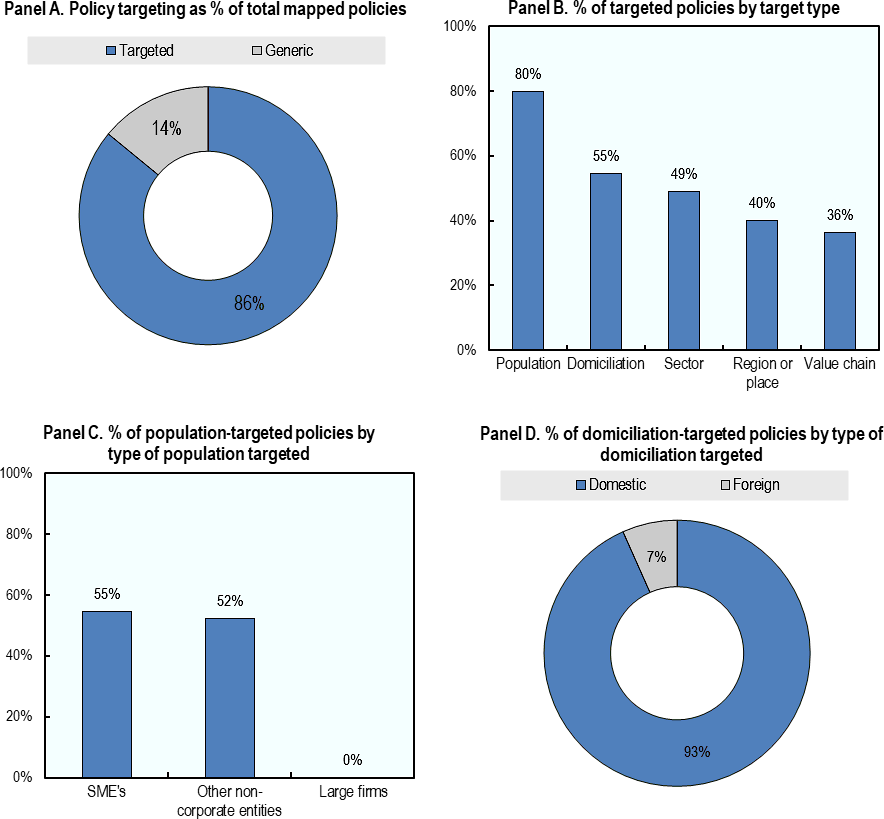

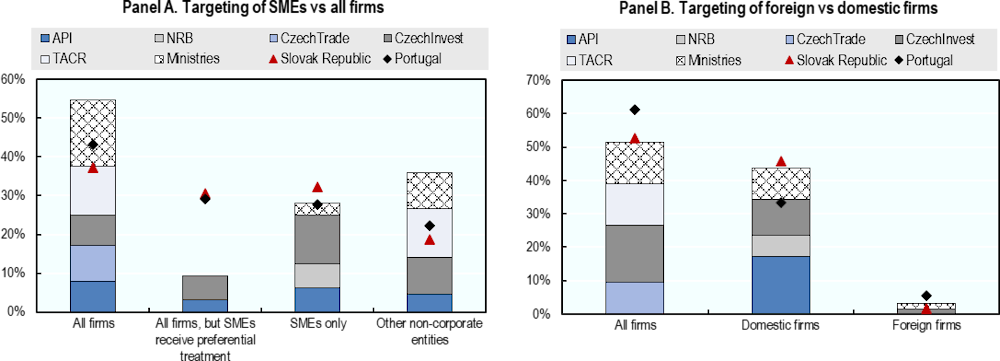

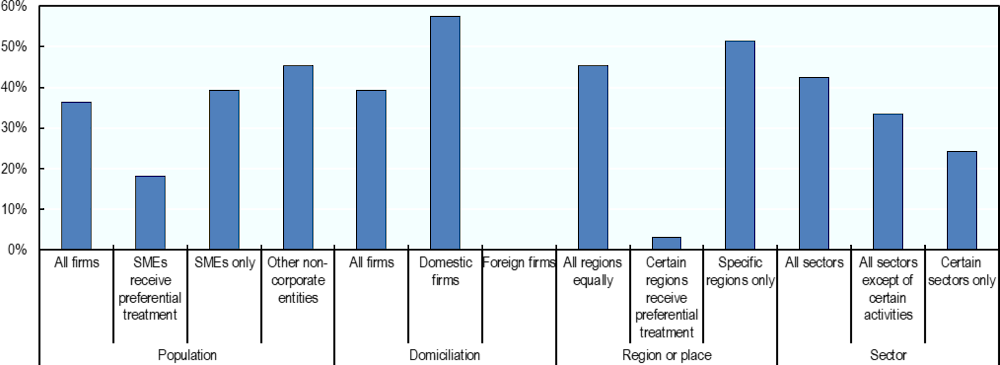

Policies aiming to address barriers in capturing spillovers from FDI to SMEs in Czechia predominantly consist of initiatives aimed a specific populations, sectors of the economy, or sub-national areas. Typically, these policies combine generic measures with targeted initiatives that aim at specific populations, sectors of the economy, or sub-national areas to address barriers in capturing spillovers. In Czechia, targeted policies represent 86% of the 64 mapped policies (Figure 5.5, Panel A), and many of them simultaneously target several dimensions.

Czech policies are primarily designed to support specific populations, particularly SMEs and non-corporate entities, to enhance knowledge transfer and improve access to funding. Policies aimed at a specific population represent 80% of all targeted policies (Figure 5.5, Panel B). SMEs and non-corporate entities are the main beneficiaries of the support (Figure 5.5, Panel C). Initiatives tailored for SMEs specifically or providing preferential conditions to them are supported by policies targeting such non-corporate entities as universities and research centres, which aim to ease the transfer of knowledge to local SMEs. Meanwhile, policies towards private investors, business angels and venture capital funds contribute to improving SMEs’ access to funding.

Czechia has a significant focus on supporting domestic firms. More than half (55%) of policies are targeting specific domiciliation of firms and 93% of these initiatives are designed to aid domestic SMEs and entities (Figure 5.5, Panel D). This indicates a strong emphasis on bolstering local businesses. Meanwhile, only 3% of these policies aim to assist foreign companies in entering and operating in the Czech business environment. This could imply that while Czechia is fostering its domestic SMEs, there might be room to increase efforts in attracting and facilitating foreign companies, which could further enhance FDI-SME linkages.

In assessing the targeted nature of Czech FDI-SME policies, it's crucial to weigh both the benefits and potential risks. On the positive side, these targeted policies, focusing on SMEs and non-corporate entities such as universities and research centres, ensure that resources are concentrated where they can be most effective. This approach enhances knowledge transfer and improves access to funding, which is vital for these entities that might otherwise struggle to compete with larger corporations. However, there are inherent risks in such a targeted strategy. It may lead to a disproportionate allocation of resources, potentially overlooking other sectors of the economy that could also benefit from similar support. This could result in a lack of balanced economic development and might inadvertently create dependencies or reduce incentives for broader-based innovation and competitiveness. The focus on specific regions or sectors might lead to inefficiencies or inequities if not managed with a comprehensive understanding of the broader economic ecosystem. While targeted policies have their merits, a careful and dynamic approach is needed to ensure they do not inadvertently skew the market or hinder wider economic growth.

5.2.5. Czechia supports its SME ecosystem through a local focus and chain integration.

Czechia’s smart specialisation strategy aims to create long-term competitive advantage by attracting more knowledge-intensive FDI and enhancing the innovation capacity of SMEs in selected priority sectors. Policies with a sectoral focus represent 49% of targeted policies (Figure 5.5, Panel B). These measures either target selected sectors or exclude them from their scope of application. By encouraging the technological upgrading of specific industries, governments intend to attract more knowledge-intensive FDI while helping SMEs operating in those industries scale up their innovation capacity. The Czech Ministry of Industry and Trade's National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation (RIS3) 2021–2027 aims to foster a competitive edge in key sectors like advanced materials, digital and green technologies, and smart cities by focusing on smart specialisation areas with significant potential for knowledge-based innovation and long-term growth.

Figure 5.5. Most FDI-SME policies in Czechia target specific populations, domiciliation, sectors, regions, or value chains

Copy link to Figure 5.5. Most FDI-SME policies in Czechia target specific populations, domiciliation, sectors, regions, or value chains

Note: Panel A: Shares of generic and targeted policies as a percentage of the total 64 policies mapped. Panel B: Shares of policies by target type, as percentage of total targeted initiatives (55). As policies can be directed at more than one type of target, the sum is above 100%. Panel C: Shares of policies by type of population targeted, as percentage of total population-targeted policies (44). SMEs-targeted policies include initiatives applying to SMEs only or providing preferential conditions to them. Other non-corporate entities include investors (business angels, venture capitalists or VC funds, banks, financing institutions, etc.); universities; research organisations; entrepreneurs; individuals with specific roles or skillsets (e.g., managers, highly-skilled, researchers); government institutions and sub-national governments (e.g. municipalities); and others. Panel D: Shares of policies by type of domiciliation targeted, as percentage of total domiciliation-targeted policies (30). It demonstrates distribution of policies specifically targeting domestic or foreign firms.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

A place-based approach of Czech policies indicates a strategic focus on regional development of economically and socially vulnerable areas, with 40% of targeted policies taking a place-based approach (Figure 5.5, Panel B). This includes policies targeting specific geographic areas only or giving them preferential treatment. For example, initiatives implemented by Business and Innovation Agency give preferential treatment to economically troubled regions and territories with a high unemployment rate. CzechInvest focuses its investment incentives on economically and socially endangered areas according to the Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ and structurally disadvantaged areas like the Moravia-Silesia, Ústí and Karlovy Vary regions. By doing so, they seek to attract FDI to these areas and foster the growth and development of local SMEs, thereby facilitating the creation of FDI-SME linkages that can contribute to regional economic resilience and prosperity.

There is a strategic emphasis on enhancing the competitiveness and integration of SMEs within different value chains in Czechia. Thirty-six percent of targeted policies focus on specific value chains (Figure 5.5, Panel B). These initiatives aim to attract FDI into sectors where Czech SMEs are active or have growth potential. This can facilitate technology transfer, enhance local capacity, and foster innovation, thereby strengthening the linkages between foreign investors and local SMEs.

5.2.6. Market openness may facilitate FDI spillovers on Czech SMEs, but the regulatory burden on business, barriers to competition, and labour market restrictions could be reduced

In addition to targeted measures, the quality of the broader regulatory environment also shapes the performance of national FDI-SME ecosystems and the potential for FDI knowledge and technology spillovers to domestic SMEs. Factors such as openness to foreign investment, fair competition rules, the protection of intellectual property rights, and a labour market policy regime that facilitates the mobility of skilled workers need to be in place for economies to reap the benefits of FDI spillovers.

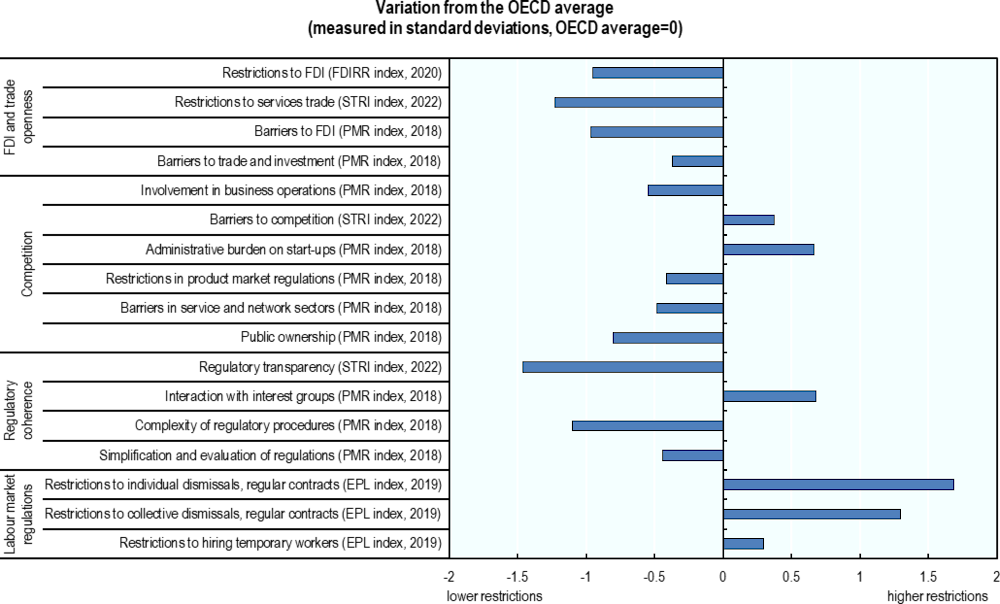

Czechia maintains a relatively open economy within the OECD (Figure 5.6). The government's approach to FDI is positive, fostering an environment that is generally welcoming and non-discriminatory toward foreign investors. Recent legislative efforts in Czechia have aimed at enhancing the business climate, emphasizing the simplification of regulations and reduction of regulatory complexity. While these measures indicate a commitment to improving the overall regulatory environment, certain OECD indicators suggest challenges in the long-term predictability of regulations affecting the business landscape. Labour market regulation remains an area for improvement, and there are concerns about administrative burdens on start-ups, barriers to competition and regulation surrounding interaction with interest groups (Figure 5.6). These aspects may present obstacles for both domestic and foreign enterprises seeking to operate in Czechia.

Figure 5.6. Czechia’s performance in key regulatory framework areas

Copy link to Figure 5.6. Czechia’s performance in key regulatory framework areas

Note: Data bars pointing left show lower regulatory restrictions than the OECD average, and data bars pointing right show higher restrictions.

Source: OECD elaboration based on the FDIRR, STRI, PMR and EPL indices.

5.3. Policies acting upon the enabling environment

Copy link to 5.3. Policies acting upon the enabling environment5.3.1. Attracting and facilitating knowledge-intensive and productivity-enhancing FDI

Investment promotion and facilitation policies can play an important role in enhancing knowledge and technology spillovers from FDI to domestic SMEs. Investment promotion and facilitation can focus on the attraction of FDI in more productive and innovative activities and in sectors with high absorptive capacities.

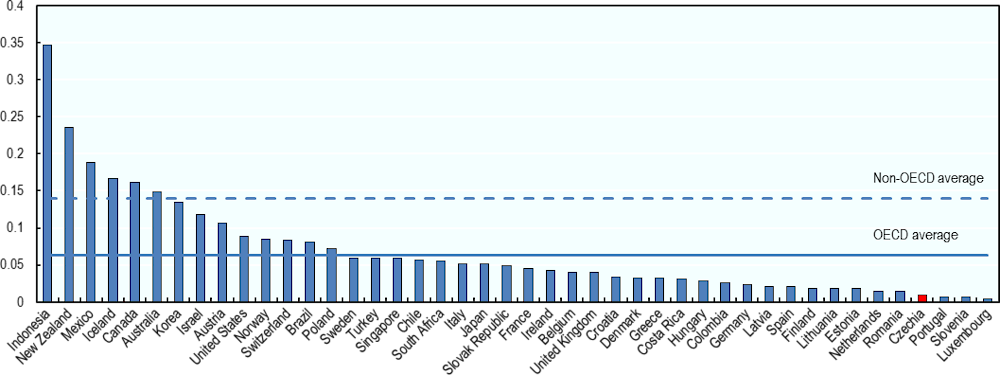

Czechia has a relatively open economy for foreign investment

The Czech economy maintains openness in its economy, fostering a conducive environment for FDI. This is characterised by minimal investment restrictions and barriers to trade. The government's approach towards FDI is notably encouraging, ensuring a non-discriminatory and supportive landscape for foreign investors (Figure 5.6). This sentiment is echoed in the OECD's Foreign Direct Investment Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (FDIRR Index), which assesses factors such as foreign equity limitations, screening and approval processes, restrictions on key personnel, and various operational restrictions. The Index reveals that Czechia ranks exceptionally well, showcasing a higher degree of openness compared to many of its peers, both within the OECD and beyond. (Figure 5.7).

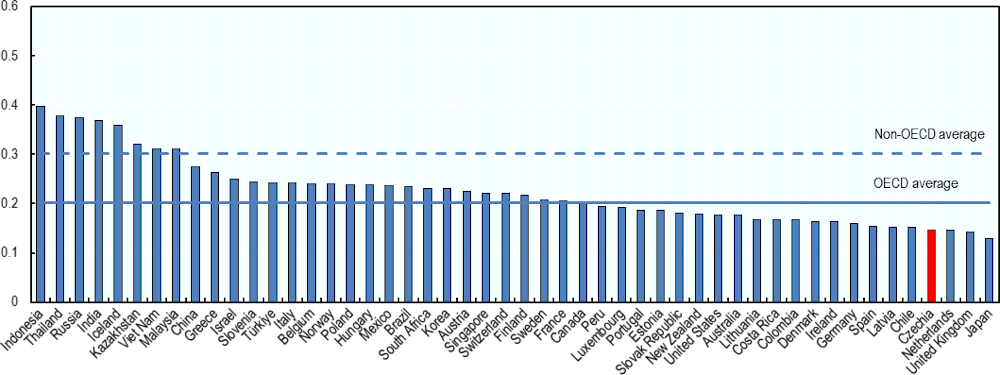

Figure 5.7. FDI restrictions in Czechia are comparatively low

Copy link to Figure 5.7. FDI restrictions in Czechia are comparatively lowOECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, 2020 (open=0; closed=1)

Note: The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index only covers statutory measures discriminating against foreign investors.

Source: OECD FDIRR database.

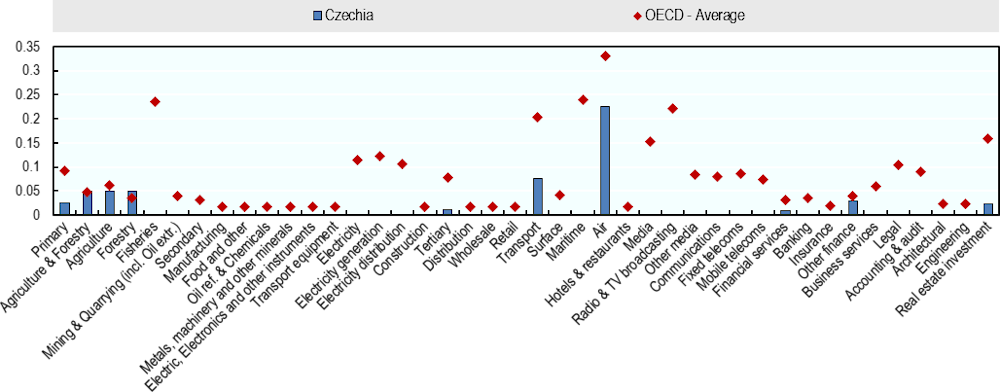

Foreign firms, in principle, have the right to establish business enterprises and engage in economic activities under conditions similar to domestic firms. However, certain sectors, e.g. agriculture and forestry, transport, real estate and financial services, had specific restrictions in 2020 (Figure 5.8). For example, for the air transportation sector, under Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 on common rules for the operation of air services in the Community, Article 4(f) states that airlines established in Czechia must be majority owned and effectively controlled by EU states and/or nationals of EU states, unless otherwise provided for through an international agreement to which the EU is a signatory.

Figure 5.8. FDI restrictions in Czechia across 22 economic sectors

Copy link to Figure 5.8. FDI restrictions in Czechia across 22 economic sectorsOECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, 2020 (open=0; closed=1)

Note: The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index only covers statutory measures discriminating against foreign investors.

Source: OECD FDIRR database.

While the overall regulatory environment is conducive to FDI, as mentioned above, specific challenges may exist. In terms of the regulatory framework, efforts have been made to simplify regulations and reduce complexity, aligning with broader initiatives to enhance the business climate. However, as shown by OECD indicators, long-term predictability of regulations affecting the business environment may be an area for improvement (Figure 5.6). Transparency in legislative processes could be enhanced, and concerns persist regarding administrative burdens, including bureaucratic hurdles, lengthy administrative procedures, and frequent changes to laws and programme rules.

In 2021, the Czech government adopted the Foreign Investments Screening Act, which introduced a screening mechanism for non-EU FDI deemed to threaten the country’s security or internal and public order (Box 5.3). This mechanism is the first instrument of its kind in Czechia’s recent history (OECD, 2022[20]). The legislation was adopted amidst a global trend towards the adoption or revision of FDI screening mechanisms which emerged since around 2016 and accelerated further in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, both of which heightened concerns about potential foreign takeovers in sensitive sectors (OECD, 2023[8]). Recent OECD work on FDI screening mechanisms in the EU documents that similar screening frameworks have been adopted since 2021 by several other EU countries, with political impetus that resulted from the entry into force of the EU FDI Screening Regulation which establishes a legal framework for EU Member States’ cooperation on FDI screening as a complementary driver (OECD, 2022[20]).

While evidence on the impact of the new FDI rules on international investment inflows in Czechia is not yet available, it emphasises the need for a careful and balanced approach to FDI-SME policymaking. This will be even more relevant in Czechia as the country moves ahead in the implementation of the new screening provisions, so as to enhance its ability to address essential security concerns without weakening investment promotion efforts. Screening authorities from across EU Member States have expressed concerns about the potential disadvantage that screening could generate in the context of efforts to attract foreign investment, especially when competing with similarly positioned countries outside the EU that do not screen inward investment (OECD, 2022[20]). Tailored policy practices will need to be identified to enhance the predictability, transparency, and administrative efficiency of the Czech screening regime, by clarifying the procedural rules applicable to investors, and providing decision-making guidance for the implementing authorities.

Box 5.3. The Foreign Investments Screening Act 2021

Copy link to Box 5.3. The Foreign Investments Screening Act 2021The Foreign Investments Screening Act was adopted by the Czech Parliament on 3 February 2021 and took full effect on 1 May 2021. It was introduced in response to EU Regulation 2019/452, which establishes a framework for the screening of FDI into the European Union. The screening rules adopted by individual EU Member States vary considerably in scope and operation (OECD, 2022[20]). The Czech FDI Act establishes a screening process for certain investments from countries outside the European Union, including Switzerland, European Economic Area members like Liechtenstein and Norway, and the post-Brexit United Kingdom. These rules are designed to address investments that threaten to security or public order.

The law designates the Czech Ministry of Industry and Trade as a statutory government body responsible for conducting the screening. The rules envisage two categories of FDI screening. Mandatory prior approval from the Ministry is required for investment targeting specified industries, namely:

manufacturing, R&D&I, or life cycle administration of military material

operation of critical infrastructure (e.g., energy, gas, heat, water, food, healthcare, transportation, emergency services, financial markets and public administration)

administration or operation of critical information and communication systems and cybersecurity

manufacturing of dual-use goods (including software and technology)

Additionally, a mandatory consultation procedure (but not a prior authorisation requirement) exists for certain types of media investments (e.g., national TV or radio licence).

Even if an FDI does not require mandatory prior approval under the Act, the Czech government has discretionary power to undertake an ex post review of any FDI if it determines that such investment has the potential to affect the security or internal and public order of Czechia. FDI can be screened by the Ministry retrospectively for up to five years from the date of the investment.

To avoid a retrospective screening, foreign investors may voluntarily request prior consultation of the Ministry as to whether the prospective investment is to be subject to review. If the result of this consultation is negative, this removes the possibility of later ex officio screening of the same investment by the Ministry (Act No. 34/2021 Coll., 2021[21]). A detailed description of the functioning of the Czech legislation is available in (OECD, 2022[20]).

The screening rules may impact non-EU investment inflows in Czechia. The First Annual Report on Foreign Investments Screening in Czechia was published in 2022 and accounted for the period between 1 May 2021 and 30 April 2022 (Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Czech Republic, 2022[22]). The report does not share detailed information about specific cases, but states that among 12 investment projects investigated over the period under review, no transaction has been prohibited by the Czech authorities. Nevertheless, in two cases investors withdrew their filing (Janda, 2023[23])..

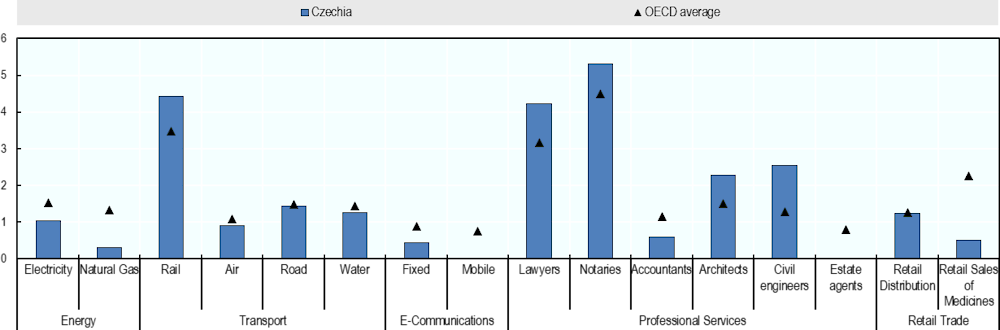

In Czechia, potential “beyond‑the-border” restrictions in the services sector could undermine recent policy efforts to diversify the economy beyond low value-added manufacturing and towards knowledge-intensive services. Beyond FDI restrictions, other “beyond-the-border” regulations – including e.g. restrictions in trade, barriers to competitions and other discriminatory measures affecting market access conditions in different sectors and industries – can influence the degree of FDI local embeddedness and the potential for value chain linkages with domestic SMEs. According to the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), Czechia’s 2022 score is one of the lowest across OECD countries, reflecting the country’s relatively open and stable regulatory environment for trade in services (Figure 5.9). Accounting services, commercial banking and insurance, computer, logistics, broadcasting, motion pictures, sound recording, road freight transport and courier services are the most open sectors while air transport and legal services are the most restricted. Overall, conditions on the entry of natural persons seeking to provide services in the country on a temporary basis as contractual services suppliers remain more cumbersome than international best practice, while rights of access to public procurement are limited to regional trade agreement partners and members of the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement. Other business requirements also apply in certain sectors, such as depositing a minimum amount of capital in a bank or with a notary to register a business. Despite these sectoral restrictions, Czechia’s overall regulatory framework for market access remains rather lenient compared to other OECD and EU countries.

Figure 5.9. Restrictions to services trade are below OECD average

Copy link to Figure 5.9. Restrictions to services trade are below OECD averageOECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, 2022 (open=0; close=1)

Note: The OECD STRI indices take values between zero and one, one being the most restrictive. The STRI database records measures on a Most Favoured Nations basis. Preferential trade agreements are not taken into account. Air transport and road freight cover only commercial establishment (with accompanying movement of people). The indices are based on laws and regulations in force on 31 October 2019.

Source: OECD STRI database, 2022.

Financial support and technical assistance are the most common instruments to attract and facilitate productivity-enhancing FDI

Czechia boasts a diverse range of incentive programmes, from tax allowances to direct grants, designed to entice both domestic and foreign investors across various sectors, including technology, manufacturing, and business support services. Czech policies for attracting FDI make a balanced use of financial support schemes (35%) and technical assistance (29%). While Czechia does not have a dedicated national FDI strategy as outlined in Chapter 4, it effectively integrates FDI policy considerations within its broader national strategies and plans. These integrations represent 29% of all policy instruments utilised, underlining the nation's commitment to enhancing productivity through the facilitation and attraction of FDI (Figure 5.10).

The set of instruments used is more diversified than in some peer countries. Czechia has in place all types of policy instruments for supporting productivity-enhancing FDI, including regulatory measures as well as networks and collaboration platforms and infrastructures in addition to financial schemes and technical assistance services, while peer countries such as Germany and Poland focus on fewer types of instruments (Figure 5.10).

Figure 5.10. Policy instruments for attracting productivity-enhancing FDI in Czechia and selected peer economies

Copy link to Figure 5.10. Policy instruments for attracting productivity-enhancing FDI in Czechia and selected peer economies% of all mapped policies supporting productivity-enhancing FDI

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives aimed at attracting and facilitating productivity-enhancing FDI. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Czechia proposes a comprehensive package of investment incentives providing financial support to reduce investment costs. Pursuant to Act No. 72/2000 Coll. on Investment Incentives, as amended, financial incentives are available to support investment by both domestic and foreign companies for the launch of new operations or the expansion of activities in the areas of manufacturing, technology centres or business support centres (including shared-services, software development, high‑tech repair or data centres). Incentives mainly take the form of corporate income tax relief and direct grants for the creation of new jobs and the training or re-training of staff. The intensity of investment aid may vary depending on the size of the investing company, the volume of the investment, as well as the region and sector where the investment takes place. For example, an additional cash grant of capital investment up to 10-20% of eligible costs (depending of the region) is available for strategic manufacturing investment of at least CZK 2 billion and generating a minimum of 250 new jobs; as well as for higher value added investment in high-tech manufacturing sectors (pharmaceutical products and preparations; computers, electronic and optical devices; aircraft and their engines; spacecraft and related equipment) (CzechInvest, 2021[26]; Czech Business Guide, 2022[27]; Czech Government, 2021[28]).

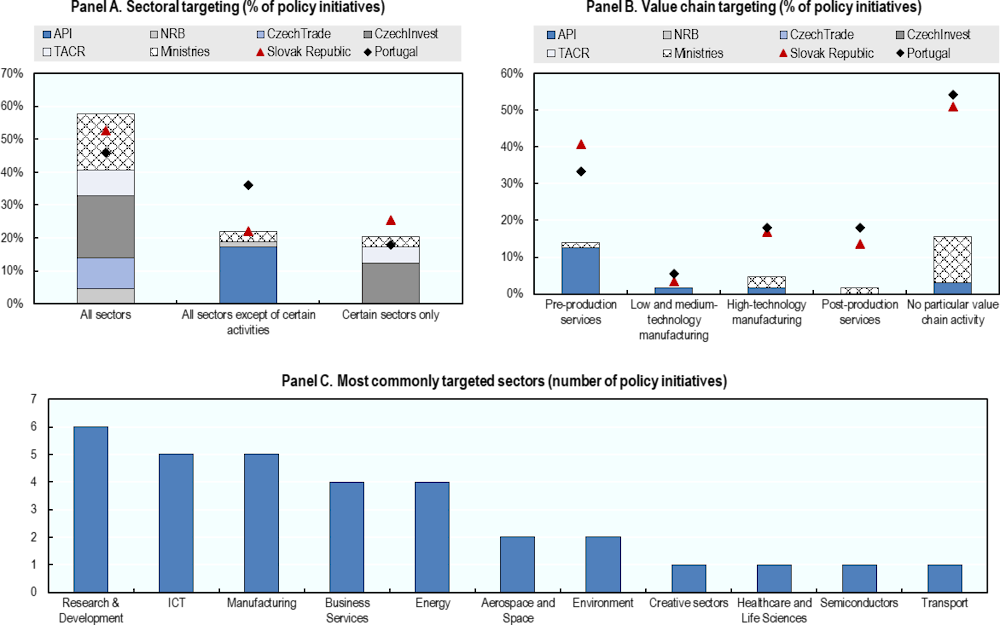

Czechia’s policy framework differentiates incentives based on the scale of investment, targeted sectors, and regional needs, to address the demands of investment projects and regional economic conditions. In the overall policy mix, 20% of policies enabling FDI diffusion on domestic SMEs target specific industries (Figure 5.11, Panel A). R&D-intensive activities in high-value sectors such as pharmaceuticals, electronics, and aerospace are strongly prioritized, aligning investments with the Czechia’s strategic economic goals and fostering innovation in key industries (Figure 5.11, Panel B and Panel C). For example, in manufacturing, technology centres, business support service centres, and strategic product production, Czechia’s investment incentives include corporate income tax relief for up to a decade, job creation grants, training support, and additional cash grants (CzechInvest, 2021[26]; CzechInvest, 2021[29]). These measures, tailored based on firm size, sector, and strategic significance, underscore the country's commitment to supporting diverse industries and encouraging long-term investments.

Figure 5.11. Sectoral and value chain targeting of Czechia’s overall policy mix

Copy link to Figure 5.11. Sectoral and value chain targeting of Czechia’s overall policy mix

Note: The following value chain activities are considered: i) Pre-production services: R&D, concept development, design, patents; ii) Low and medium-technology manufacturing: production of simple, relatively unsophisticated goods such as basic metals, plastic products, food, textiles, etc.; iii) High-technology manufacturing: production of highly specialised, technologically sophisticated goods such as computer and electronic products, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, medical products, etc.; iv) Post-production services: marketing, sales, logistics, brand management, distribution and customer services.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Innovative programmes focusing on brownfield sites reflect Czechia’s commitment to sustainable development. These programmes leverage financial aid and technical support to revitalize existing industrial infrastructure. Notable initiatives such as the NPO Brownfields programme of the Ministry of Regional Development and the Operational Programme Environment of the Ministry of Environment, both of which facilitate investments in brownfield regeneration. These initiatives are supported by funding from the state budget and EU structural funds. The Smart Parks for the Future programme, overseen by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, provides subsidies to municipalities, cities, and regions for brownfield site regeneration and the enhancement of existing industrial infrastructure. CzechInvest, through its national database, orchestrates a comprehensive set of programmes aimed at brownfield valorisation and regeneration, further enriching the investment landscape.

Higher aid intensity for SMEs encourages their participation, promoting inclusive economic growth and job creation within local communities. Several policies for productivity-enhancing FDI-SME linkages found in Table 5.2 are relevant for SMEs specifically. For example, through R&D Tax Allowance’s SMEs engaged in research and development activities can benefit from deductions on specific R&D expenses, such as personnel costs and materials, reducing their taxable income. SMEs seeking investments or collaborations can utilize Czechlink (for Investors) to connect with potential investors and partners, fostering growth opportunities. SMEs expanding their business in Czechia can access expert advice on legislation, business environment, and funding options, facilitating their entry into the market through AfterCare. To support further productivity growth, Czechia could use examples of tax incentives adopted by different EU countries targeting employment, innovation, and skills development (Box 5.4).

Table 5.2. Main policies for productivity-enhancing FDI-SME linkages

Copy link to Table 5.2. Main policies for productivity-enhancing FDI-SME linkages|

Main policies |

Description |

Implementing Institution |

|---|---|---|

|

R&D tax allowance |

Specific R&D expenses can be fully deducted from the tax base in a given year, covering direct costs like personnel and materials, tax depreciation of assets, and other operational expenses related to R&D activities. |

Ministry of Finance |

|

Czechlink (for investors) |

Platform to connect companies that are looking for an investor and investors who intend to acquire assets of a local company. |

CzechInvest |

|

AfterCare – support for companies doing business in Czechia |

The programme offers to foreign companies expert advice on the Czech business environment, including legislation, investment incentives, and financing options. It facilitates connections with qualified employees, partners, universities, research organizations, and government authorities to support business expansion. |

CzechInvest |

|

Real estate database |

The database connects municipalities and private owners with investors, allowing them to offer real estate properties directly. It assists investors in specifying suitable sites for their projects. |

CzechInvest |

|

National Brownfields Database |

The database catalogues eligible brownfield sites, offering them to investors. It provides insights on brownfield numbers and characteristics for public use and compiles data for regeneration efforts. |

CzechInvest |

|

Investment incentives for manufacturing |

The manufacturing industry incentives offer CIT tax relief for a decade, job creation grants, and training aid, with higher support for SMEs. Strategic investments over CZK 2 billion creating 250+ jobs get additional cash grants if using key technologies like pharmaceuticals or electronics. |

CzechInvest |

|

Investment incentives for technology centres |

These incentives offer CIT relief for a decade, job creation and training grants based on investment size and jobs created. SMEs receive higher support, and strategic investments over 200 million CZK with 70+ jobs get an extra 20% cash grant. |

CzechInvest |

|

Investment incentives for business support service centres |

These incentives offer CIT relief for a decade if a minimum number of new jobs are created across three countries. SMEs receive higher support, and strategic investments over 200 million CZK with 100+ new jobs get an extra 20% cash grant. |

CzechInvest |

|

Investment incentives for the production of strategic products |

These incentives provide CIT relief for a decade, job creation grants, training support, and up to 20% cash grants for strategic health-related investments. Support varies based on firm size, region, and investment volume. SMEs receive increased aid. |

CzechInvest |

|

Czech Foreign Investments Screening Act |

The national screening mechanism assesses potential foreign investments for negative effects on security or public and internal order. The Act authorises the Ministry to impose conditions on certain non-EU investments or to prohibit such investments. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Box 5.4. Targeting employment, innovation and skills development through tax incentives

Copy link to Box 5.4. Targeting employment, innovation and skills development through tax incentivesMany governments use tax incentives to target employment and skills development, for example through CIT allowances or credits, or through reductions or exemptions to other taxes such as social security contributions. CIT incentives can address employment outcomes by linking benefits to qualifying expenditure (e.g., wages or payroll expenses) or outcome conditions (e.g., creating a minimum number of new jobs). By using dedicated eligibility conditions and design features, incentives can support existing jobs, or encourage beneficiaries to create new jobs or invest in training opportunities of staff. Sometimes these goals overlap with other priorities; many countries that support employment costs via incentives also encourage skills development or promote R&D.

Reducing employment costs through tax credits

France has offered different tax credits to target employment costs. The Competitiveness and Employment Tax Credit (CICE) amounted to 6% of annual payroll charges paid and could be claimed for salaries that are up to 2.5 times the amount of the French minimum wage. It thereby significantly decreased the costs of medium and low wages. In 2019, a reform permanently decreased employers’ social contributions and phased-out the credit.

France introduced a hiring credit to counter the effects of the 2008 recession. The credit relieved firms from paying social contributions for new employees hired between December 2008 until the end of 2009. It targeted small firms with less than ten employees and low-wage jobs. An econometric assessment of the credit found that it had a statistically positive effect on job creation (Cahuc, Carcillo and Le Barbanchon, 2019[30]). The success of the measure was due to certain design features: the credit was temporary, targeted at jobs with rigid wages and not anticipated by the labour market.

Targeting employment and innovation

In the Netherlands, investors can benefit from an employment incentive if their business is engaged in R&D activities. The country offers a payroll withholding tax credit (also known as the WBSO R&D credit scheme) that reduces wage costs of R&D employees. Such an incentive has the potential to boost employment and could generate knowledge spillovers, if researchers acquire skills on the job that they can transfer to other jobs. The incentive may also attract innovative companies. The benefit amounts to 32% for the first EUR 350.000 of R&D costs and 16% if expenses (wages or other expenses) exceed the threshold.

Tax allowances can support skills development

Italy offers a tax allowance for companies investing in training of staff for Industry 4.0. The goal is to support the up-skilling of staff related to the technological and digital transformation of businesses. Large companies can deduct 30% and medium-sized companies additional 50% of training costs from their taxable base, caped at max. EUR 250,000. For small companies, these thresholds increase to 70% of respective costs, caped at EUR 300,000.

Incentives for investments in digital upgrades

Under Australia’s Technology Innovation Boost programme, small businesses with annual turnover of less than USD $50 million can claim a 20% enhanced deduction (120% tax deduction) for cost of expenditures and depreciating assets up to a threshold. Eligible expenditure includes digital solutions such as portable payment devices, cyber security systems and subscriptions to cloud-based services.

5.3.2. Strengthening the absorptive capacities of Czech SMEs

Measures aimed at enhancing the ability of local SMEs to absorb external support can manifest in diverse ways, such as subsidies, grants, loans, tax relief, infrastructure development, and training programmes. These initiatives are designed to address different facets of SME performance, including access to innovation assets, skills, and finance. In Czechia, most policies aiming to scale up the absorptive capacity of SMEs make use of financial instruments (69%) and to a lesser extent from non-financial support, broader governance arrangements, such as national strategies and plans (20%), or in the form of technical assistance (18%). A smaller share of measures (7%) supports SMEs innovation and performance through infrastructure and platforms facilitating networking and collaboration (Figure 5.12).

This policy mix does not substantially diverge from that of peer countries. There are, however, some differences. Czechia has a lower proportion of technical support services for SMEs in the overall policy mix than most peer economies. By contrast, the use of governance frameworks such as national strategies or plans is more widespread than in any benchmark countries, except Portugal and the Slovak Republic (Chapter 4).

Figure 5.12. Policy instruments for SMEs absorptive capacities in Czechia and selected peer economies

Copy link to Figure 5.12. Policy instruments for SMEs absorptive capacities in Czechia and selected peer economies% of all mapped policies supporting SME absorptive capacity

Note: Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives aimed at supporting SME absorptive capacities. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Considerable targeting of SMEs is also observed in the overall policy mix. More than 37% of the policy initiatives assessed for the purpose of this study target SMEs only or provide preferential treatment to them in the form of lax requirements and conditionalities or prioritisation in their selection as recipients of public support (Figure 5.13, Panel A). This trend reflected by Czechia’s implementation of a comprehensive strategy to support SMEs for the period 2021-2027, which has been developed by the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT). Non-corporate entities such as universities, research institutes and technology transfer offices are also significantly involved (36% of the policy initiatives assessed) in policies implemented by innovation-focused government agencies such as the TA CR, CzechInvest, and API. Even though the research shows that more than 50% of Czech initiatives are open for all firms in terms of their domiciliation, the level of policy targeting of the only domestic firms is notable (44% of the policy initiatives assessed). Targeting of the only foreign firms receive less attention (Figure 5.13, Panel B).

Figure 5.13. Policies targeted to SMEs versus generic policies (% of policy initiatives)

Copy link to Figure 5.13. Policies targeted to SMEs versus generic policies (% of policy initiatives)

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Czechia's policy framework is designed to boost SME innovation, enhance their absorptive capacities, and support internationalisation, aiming to maintain their global competitiveness.

Czechia has implemented a comprehensive set of policies through various initiatives to enhance the absorptive capacities of its SMEs, fostering innovation, internationalisation, and collaboration (Table 5.3). In a concerted effort to propel SMEs onto the global stage, Czechia has instituted a suite of initiatives that facilitate international exposure, networking, and mentorship. Programmes like Czech Demo, Czech Match, and CzechAccelerator play pivotal roles in extending the reach of Czech SMEs and fostering a globally competitive environment.

The connectivity platforms, Czechlink and Czechlink Start-up, exemplify the commitment to cultivating investor relations and nurturing start-ups. These platforms serve as catalysts for dynamic ecosystems, enabling companies to connect with investors seamlessly. Furthermore, the mentorship programme, CzechStarter, acts as a cornerstone for entrepreneurial development, embodying a supportive framework for nascent businesses.

Czechia's innovation landscape receives a significant boost through the ESA BIC Czechia collaboration with the European Space Agency. By providing mentoring, business support, and discounted office spaces, this initiative propels SMEs operating in space technologies towards cutting-edge innovation. Additionally, the Sectoral Database of Suppliers contributes to transparency, fostering partnerships and joint ventures between foreign investors and domestic suppliers.