This chapter focuses on factors that underpin the governance framework for foreign direct investment (FDI) promotion and the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Czechia. It provides an overview of the institutions that are currently in place to design and implement FDI, SME, innovation, and regional development policies, and explores the policy coordination mechanisms to ensure coherence across policy domains, institutions, and tiers of government. This chapter also analyses the monitoring and evaluation framework of the Czech policy delivery system, and efforts to enhance stakeholder engagement.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Czechia

4. The institutional and governance framework for FDI and SME linkages

Copy link to 4. The institutional and governance framework for FDI and SME linkagesAbstract

4.1. Summary of findings and recommendations

Copy link to 4.1. Summary of findings and recommendationsEnhancing the impact of FDI on Czech SMEs necessitates public intervention across various policy areas, including investment promotion, SME internationalisation, innovation, and regional development. A governance framework spanning across these different policy areas and actors is not a given, and experience across countries differs. Diverse governance models can be effective, provided there are appropriate coordination mechanisms in place to ensure policy coherence across ministries, implementing bodies, and advisory entities. This chapter aims to evaluate the quality of the institutional framework in Czechia and pinpoint potential governance challenges. It offers an overview of the key institutions operating at the intersection of FDI, SME, innovation, and regional development policy. The chapter delves into their organisational structures, mandates, and activities. Additionally, it explores their internal capabilities for policy coordination, assessment, and engaging stakeholders, which are crucial elements for creating a supportive institutional environment.

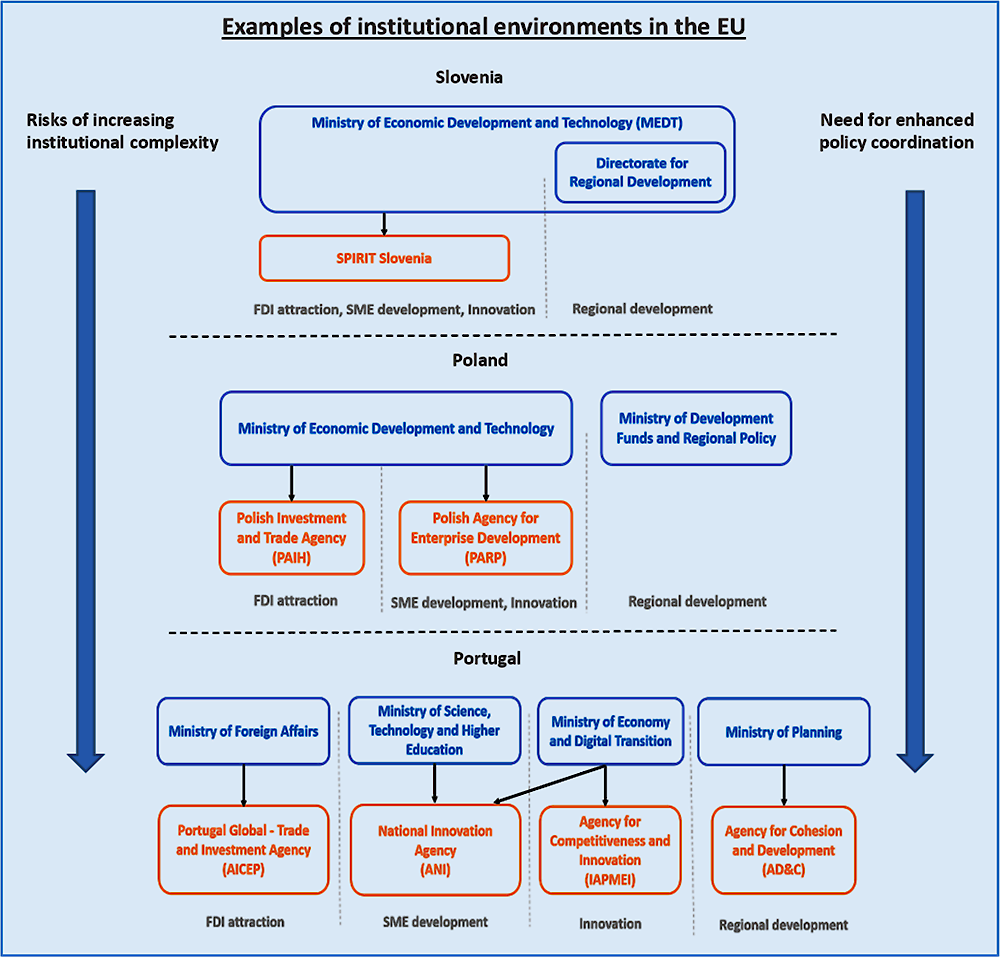

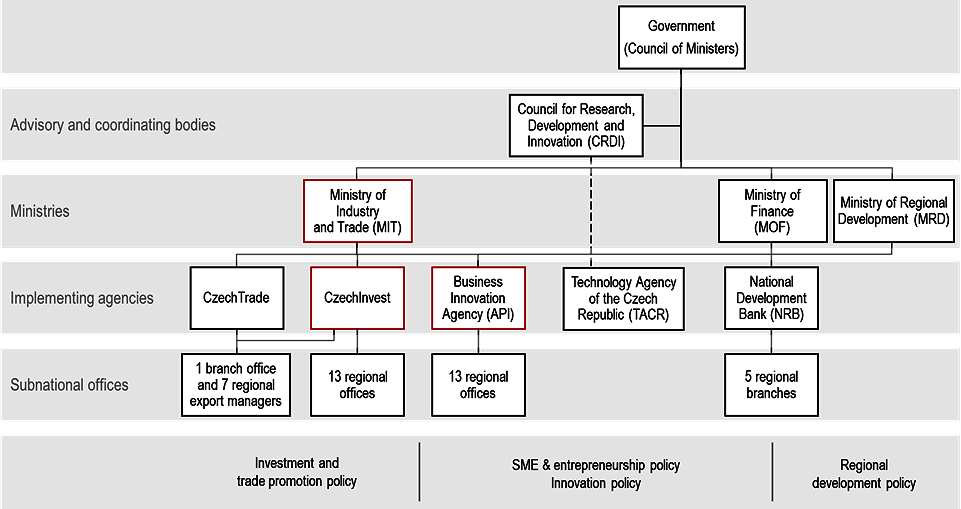

The governance framework for FDI-SME policy in Czechia is relatively integrated, yet it reveals the complexity inherent in a system where responsibilities are dispersed across numerous ministries. This structure ensures that multiple policy areas are taken into account, but may also lead to fragmentation. The Ministries involved are the Ministry of Industry and Trade (Investment Promotion through CzechInvest, SME and Entrepreneurship policy which is implemented on the administrative level through the Business Innovation Agency), the Ministry of Finance (SME and Entrepreneurship Policy and Regional Development Policy through the National Development Bank), the Ministry of Regional Development (Regional Development Policy including managing EU funds and establishing subnational business support as the main mandate). Also, the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TACR) under the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) aims to foster the innovation capacity of Czech enterprises by financing R&D activities and facilitating networking effects (Figure 4.1).

However, a prominent aspect of the Czech institutional setup is the central role played by the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT), which bears the primary responsibility for investment, SME, and entrepreneurship policy, alongside its remit in energy, industrial, and trade policy. This ministry, through its multiple departments highlighted in red in Figure 4.1, is responsible for policies related to SMEs and FDI-SME linkages. However, responsibilities are distributed across several departments, reflecting a broader policy perspective that integrates SME aspects into wider economic objectives. While various departments within the MIT often collaborate, particularly in policies related to FDI-SME linkages, this cooperation typically relies on informal channels, highlighting a potential area for more structured and formalised mechanisms.

The observed differences between the implementation of national policies at the local level suggest an opportunity for enhancing cooperation among ministries, national implementing agencies, their regional branches, and regional innovation centres (which are typically established by regional governments and have no direct link to national ministries). This enhancement could facilitate better alignment between national objectives and local actions, ensuring a more harmonious policy execution process and ensure the connection between national, regional, and local delivery of FDI, SME and innovation services. Increasing coordination between regional innovation centers and implementing agencies (CzechTrade, CzechInvest, API) one-stop-shops, and business consultation centres can be a step in the right direction. To enhance the effectiveness of this collaboration, greater tailoring of national policies at the subnational level should be combined with due coordination among national agencies operating locally and regional innovation agencies through regular meetings and consultations on an ad hoc basis.

In Czechia, several strategic documents have been adopted in recent years to articulate priorities related to strengthening FDI and SME linkages. National strategies and action plans can be important instruments for policy coordination as they are crosscutting in nature, but they often require a whole-of-government approach to ensure their effective implementation and the number of different strategic documents in Czechia heightens the risk of making policy coordination more complex. The Czech strategies collectively address a wide range of areas including skills development, digital transformation, research and development, international market access, and low-carbon economy initiatives. The strategies are implemented through a collaboration of government bodies, with a significant role played by the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) and the Ministry of Industry and Trade. The investment promotion area represents a notable exception to the trend, as Czechia does not have a national investment strategy. Investment policy considerations are incorporated in broader strategic documents.

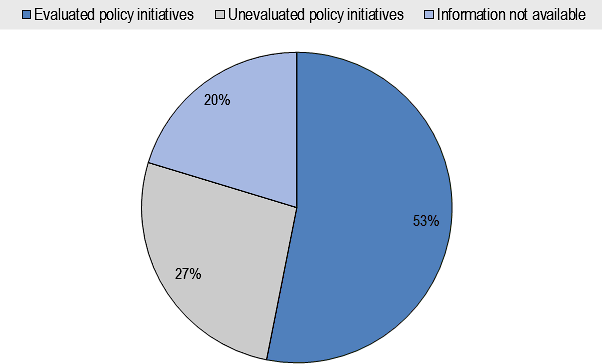

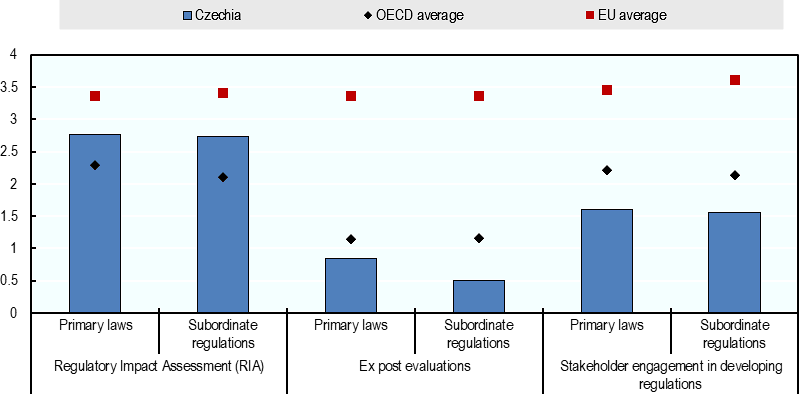

In terms of policy development and evaluation, in Czechia there is a notable opportunity to implement comprehensive evaluation frameworks to gauge policy impacts effectively. In Czechia more than half of FDI-SME diffusion policy initiatives have integrated M&E and Czechia outperforms the OECD average in terms of Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) implementation. There is still however room for enhancing the M&E framework of policies in Czechia.

The current governance structure also shows gaps in involving a broader spectrum of stakeholders, including SMEs and local communities, in the policymaking process. This suggests an avenue for fostering richer and more varied inputs into policy formulation and evaluation, as well as the necessity to establish robust feedback mechanisms for building more responsive governance structures. These mechanisms can serve as valuable tools for ongoing policy refinement, ensuring that policies remain relevant and effective in achieving their intended outcomes.

One of the notable attributes of the Czech institutional framework is its ability to balance comprehensive policy development with a nuanced understanding of the specific needs of SMEs and FDI-SME linkages. The framework’s emphasis on coordination across various policy areas and government levels ensures that policies are not developed in isolation, but rather in a manner that reflects the interconnected nature of economic growth, innovation, and regional development. This approach, coupled with the MIT’s extensive involvement in a wide range of policy areas, demonstrates the Czech government's commitment on strenghthening SMEs and their innovative capacity and, to lesser extent, enhancing the impact of FDI on the domestic economy. The utilisation of various departments within the MIT to address different facets of the SME and FDI ecosystem showcases the government’s understanding of the intricate linkages between different economic sectors and their role in fostering a robust SME sector and attracting productivity-enhancing FDI. However, it is imperative to continually evolve and adapt the institutional framework. Strengthening formal coordination channels, without compromising the existing flexibility and adaptability which are critical in a dynamic economic landscape, could serve as a valuable enhancement to the Czech government’s policy execution, ensuring that the strategic objectives are harmoniously integrated across all departments. Enhancing formal collaboration, alongside the strategic focus on coherent policy development and implementation, could stand out as a key strength of the Czech institutional framework in fostering a conducive environment for SMEs and maximizing the benefits of FDI.

Box 4.1. Policy recommendations on the Czech governance framework

Copy link to Box 4.1. Policy recommendations on the Czech governance frameworkStrengthen inter-ministerial and inter-agency coordination through formal bodies and consolidation of responsibilities to improve efficiency. In partnership with regional, publicly-funded organizations specializing in innovation services for SMEs, the establishment of such committees could actively work towards integrating the roles and responsibilities of the different ministries and agencies. This collaboration aims to leverage local expertise and resources to bolster support for SMEs. The objective would be to streamline processes and reduce duplicative efforts and roles by consolidating overlapping functions. These bodies should focus on the cohesive formulation and implementation of policies, ensuring that initiatives across different sectors and levels of government are well-aligned and mutually supportive. Such a structured approach to policy coordination will aid in achieving a unified vision in economic development and SME support.

Define clear, specialised functions for each agency to avoid overlap and focus on specific FDI-SME policy areas. To avoid overlap and enhance focus on specific policy areas, there is a need to define clear, specialised functions for each agency involved in FDI-SME policies. Each agency should have distinct mandates, with a focus on areas like startup support, SME financing, or technology adoption. This approach will prevent functional redundancy and ensure that each agency contributes uniquely and effectively to the broader policy objectives.

Create frameworks for better alignment of national policies with regional and local priorities. Greater tailoring of national policies at the subnational level should be combined with coordination among national agencies operating at local level and regional innovation agencies, to avoid an inconsistent quality of support or the provision of overlapping services in regions and places.

Implement a framework for regular impact evaluations to assess the effectiveness of FDI-SME policies, using both quantitative and qualitative metrics. This framework would provide a holistic view of policy impacts. Regular evaluations will help in identifying areas of success and areas needing improvement, allowing for timely adjustments to strategies and initiatives.

Facilitate regular, structured dialogues with a diverse range of stakeholders. Facilitating regular, structured dialogues with a wide range of stakeholders, including SMEs, local communities, industry experts, and academia, is critical. These dialogues should aim to incorporate diverse insights into policy development and evaluation processes. Engaging a broad spectrum of perspectives will enrich policy formulation, ensure that various interests and needs are considered, and enhance the overall effectiveness and acceptance of the policies.

4.2. Overview of the governance framework supporting the Czech FDI-SME ecosystem

Copy link to 4.2. Overview of the governance framework supporting the Czech FDI-SME ecosystem4.2.1. There is room to increase the integration of the governance framework supporting the FDI-SME ecosystem in Czechia

Strengthening FDI and SME linkages can be supported by public policy action in different domains. Key policy areas are investment, SME and entrepreneurship, innovation, and regional development. The institutional framework underpinning these policy areas varies from country to country, exhibiting different degrees of integration versus fragmentation, based on the number of institutions involved in policy design and implementation (OECD, 2023[1]).

The Czech governance system can be described as partially integrated. In Czechia, like in most EU countries, responsibility for the design and implementation of FDI-SME policies is shared among several implementing agencies, reporting to different ministries as seen in Figure 4.1. The Ministries and agencies involved are the Ministry of Industry and Trade (Investment Promotion through CzechInvest, SME and Entrepreneurship policy implemented on the administrative level through the Business Innovation Agency), the Ministry of Finance (SME and Entrepreneurship Policy and Regional Development Policy through the National Development Bank), and the Ministry of Regional Development (Regional Development Policy including managing EU funds and establishing subnational business support as the main mandate). The Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) holds innovation policy mandate as it oversees Czech R&D&I system and validates the allocation of R&D funds through the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TACR).

Figure 4.1. The institutional environment for FDI and SME linkages in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 4.1. The institutional environment for FDI and SME linkages in Czechia

Note: The main institutions acting upon FDI and SME linkages are designated in red. All the other institutions provide a complementary contribution to FDI and SME linkages.

Source: OECD elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023).

Czech governance framework for FDI-SME policies is not completely integrated, but less fragmented than in its peer countries such as Portugal or the Slovak Republic. In countries like Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovenia, there are single government agencies overseeing the entire FDI-SME ecosystem. Czechia’s institutional framework comprises multiple ministries in charge of different parts of FDI-SME policies, indicating a need for enhanced coordination mechanisms to bridge potential policy gaps and ensure effective collaboration across diverse domains (Box 4.2). For example, like other EU member states, there is a trend for Investment Promotion Agencies (IPA) and SME agencies to report to the same ministry, fostering potential inter-institutional collaboration for investment and SME policies.

In Czechia, the promotion of innovation and regional development is managed by a range of agencies, reflecting a common pattern seen in OECD countries In Czechia’s case, responsibilities for innovation promotion are shared primarily between the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the recently established Ministry for Research and Innovation as they both have mandates in innovation policy, while the Council for Research, Development and Innovation works an advisory body to the Government (Table 4.1). Unlike the more centralized models in some OECD countries, such as Poland or Portugal, where regional development policy is typically overseen by dedicated ministries, Czechia’s approach involves the Ministry of Regional Development, which outlines the regional development strategy (Box 4.2, Table 4.1).

However, there is a collaborative aspect in Czechia’s framework. The Ministry of Regional Development, in conjunction with the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the Ministry of Finance, supports synergies through the National Development Bank. This bank plays a multifaceted role, not only assisting SMEs with bank guarantees and preferential loans but also financing housing development and municipal infrastructure projects (Figure 4.1).

Table 4.1. Key implementing institutions acting upon the FDI-SME diffusion policy areas

Copy link to Table 4.1. Key implementing institutions acting upon the FDI-SME diffusion policy areas|

SME & entrepreneurship policy / Innovation policy |

FDI promotion and internationalisation policy |

Regional development policy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Implementing agency |

Business and Innovation Agency |

Technology Agency of the Czech Republic |

CzechInvest |

Ministry of Regional Development |

|

Date of creation |

2016 |

2009 |

1992 |

1996 |

|

Ministry in charge |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

Reports directly to the Council of Ministers |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

n/a |

|

Legal form |

Autonomous government agency |

Autonomous government agency |

Autonomous government agency |

Ministry |

|

Mandate |

Delivering EU-funded financial support programmes for businesses |

Centralizing public support to R&D&I |

Promoting, facilitating, and attracting FDI, supporting startups and SMEs |

Designing and implementing regional development policies |

|

Target population |

Established SMEs (+1 year) |

Research institutions, firms, business‑research consortia |

Foreign investors, Czech startups |

Regional and municipal authorities |

|

Priority sectors |

All sectors except agriculture, forestry, fishing, aquaculture, and steel industry |

Production technology, energy, environment, materials, digital and cyber technology, knowledge-based economy |

Manufacturing, technology centres, strategic services |

None |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023).

Box 4.2. Institutional arrangements supporting FDI and SME linkages in EU Member States

Copy link to Box 4.2. Institutional arrangements supporting FDI and SME linkages in EU Member StatesGovernance frameworks supporting FDI and SME linkages within the EU vary, ranging from highly integrated settings where FDI-SME policies are the responsibility of a single ministry or implementing agency, to fragmented institutional set ups, where the responsibility is shared among a larger number of institutions. More complex governance systems may induce higher risks of information asymmetries, transaction costs and trade-offs, and require stronger inter-institutional co-ordination mechanisms to overcome potential policy silos (OECD, 2023[1]).

In Portugal, for example, several highly specialised implementing agencies operate across the four policy areas of investment, SME and entrepreneurship, regional development and innovation, reporting to different line ministries (Figure 4.2) (OECD, 2022[2]). The primary responsibility for SME and business innovation policy lies with the Ministry of Economy and Digital Transition and its implementing agencies (the SME Competitiveness Agency (IAPMEI) and the National Innovation Agency (ANI)). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also implements national investment promotion and trade policies and supervises the work of the national IPA (AICEP Portugal Global). Important prerogatives are also in the hands of the Ministry of Planning and the Ministry of Territorial Cohesion, which are responsible respectively for the management of the EU Structural and Investment Funds and the design and implementation of economic growth policies in regions (OECD, 2023[1]).

In contrast, other EU member States with an integrated institutional framework (e.g., Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia) target the entire FDI-SME ecosystem through a single government agency reporting to one Ministry (OECD, 2023[1]). For instance, Slovenia’s Ministry of Economic Development and Technology is responsible for all policy areas related to FDI and SME linkages. A single agency, SPIRIT Slovenia, is in charge of FDI, SMEs, innovation, and tourism promotion, while regional development policy is co-ordinated through the Ministry’s Regional Development Directorate (OECD, 2022[3]). By design, the need for inter-institutional collaboration in such integrated governance frameworks is limited, facilitating coordination across policy domains.

Overall, the majority of EU member States – including Czechia – stands in between and has partially integrated governance framework (OECD, 2023[1]). In this group of countries, a common trend is for the IPA and the SME and entrepreneurship agency to report to the same ministry, which could facilitate inter-institutional planning and decision-making across the investment and SME policy agendas. Responsibilities for innovation promotion, on the other hand, are often split between the ministries responsible for economic policy, science, and education. Although investment promotion, SME and innovation policies can be more or less integrated into the same ministry, regional development policy usually stands apart, and is entrusted to a dedicated ministry. However, there are exceptions. For example, in Slovenia, as highlighted above, responsibility for regional policy sits within the Ministry of Economy (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 4.2. Governance frameworks in the EU based on institutional complexity

Copy link to Figure 4.2. Governance frameworks in the EU based on institutional complexity4.2.2. Czechia’s varied institutional landscape highlights the necessity for coordination, streamlined communication, and cohesive strategies to improve FDI-SME linkages.

The primary responsibility for investment, SME and entrepreneurship policy lies with the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT). The Ministry’s portfolio also includes the related fields of energy, industrial and trade policy.

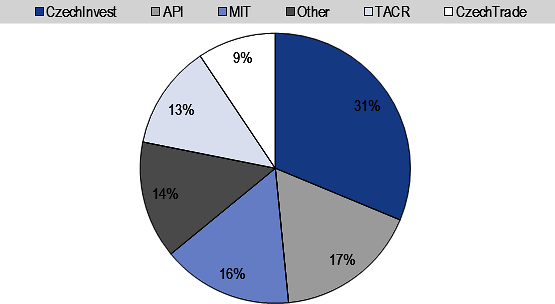

The approach to SME policy in Czechia, particularly regarding FDI-SME linkages, is managed by multiple departments rather than by a single autonomous body. This is especially apparent within the MIT, where the remit for SMEs and entrepreneurship is spread across several departments. Such an organisational structure reflects a wider policy viewpoint, considering SME aspects not in isolation, but as a fundamental, cross-sectional element of broader policy aims, inclusive of FDI-SME linkages. Whilst the various departments within the MIT engaged in SME policy often collaborate, this cooperation typically relies on informal channels, underscoring a potential area for more structured and formalised mechanisms. The Ministry is directly responsible for the implementation of 17% of the Czech policy initiatives mapped under the 2023 edition of the EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (Figure 4.3). A further 50% of the policy initiatives mapped is delivered by two of the Ministry’s implementing agencies, which play a particularly prominent role in supporting the Czech FDI‑SME ecosystem:

CzechInvest, i.e., the national Investment Promotion Agency (IPA), responsible for attracting FDI and supporting investors and entrepreneurs. In addition to the core investment promotion and attraction activities, CzechInvest’s portfolio also includes a growing number of initiatives supporting Czech startups and young firms.

The Business and Innovation Agency (API), which administers EU structural funds and supports the growth and upgrading of Czech SMEs. In particular, the agency administers business support under the EU Operational Programme Enterprise and Innovation for Competitiveness (OP EIC 2014-2020) and the Operational Program Technologies and Application for Competitiveness (OP TAC 2021-2027).

Figure 4.3. Distribution of mapped FDI-SME policies across Czech institutions

Copy link to Figure 4.3. Distribution of mapped FDI-SME policies across Czech institutions% of mapped FDI-SME policy by implementing institutions, 2023

Note: % are calculated over a total of 64 policies mapped. “Other” includes National Development Bank (NRB); Ministry of Regional Development (MRD); Research, Development and Innovation Council (CRDI); and Ministry of Finance (MoF).

Source: Author’s elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023).

The Czech Trade Promotion Agency (CzechTrade) – also established under the MIT – plays a complementary role in supporting the national FDI-SME ecosystem by promoting the export and internationalisation performance of Czech companies via a broad range of business support and matchmaking services.

The Ministry of Industry and Trade has the responsibility to design the policies, while the specialised agencies are mainly responsible for policy implementation. For example, in initiatives such as the Innovation Programme or Potential Programme, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, as the programme’s managing authority, delegates a significant portion of the implementation tasks to the Business and Innovation Agency (API). The API serves as an intermediary organisation for grant-based assistance, overseeing communication with aid applicants and recipients, including the evaluation of applications, while the Ministry of Industry and Trade retains responsibility for resource allocation and disbursement.

In addition to the MIT and its implementing agencies, other institutions also provide a prominent contribution to supporting the FDI-SME ecosystem. These include:

The Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TACR) which has important prerogatives in the area of R&D and innovation promotion. It was established in 2009 as the cornerstone of a reform project aimed at reducing the fragmentation of the Czech R&D support system. The Agency runs in-house programmes and administers R&D financial support schemes on behalf of different ministries. TACR’s programmes aim to foster the innovation capacity of Czech enterprises; support collaboration between industry and R&D organisations; and make the governance of the public support system for applied R&D more efficient by removing overlaps (OECD, 2016[4]). The TACR operates under the direct supervision of the Czech Government, through the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI).

The National Development Bank (NRB), a state-owned banking institution, also plays a crucial role in the fields of SMEs and entrepreneurship support and infrastructure development, as a major provider of financial support instruments such as preferential loans or credit guarantees. It is a joint stock company owned by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Regional Development, and the Ministry of Finance. Established in 1992 as the Czech-Moravian Guarantee and Development Bank (ČMZRB), the NRB has been supporting sustainable economic development in Czechia for almost three decades (NRB, 2023[5]).

The Ministry of Regional Development (MRD) coordinates the design and implementation of regional development policy. The Ministry provides information and methodological guidance to higher territorial self-governing units, towns, municipalities, and associations thereof. It also ensures the engagement of territorial self-governing units in European regional structures. The precise extent of the responsibilities and programmes of the Ministry are described in more detail in Chapter 6. The Ministry’s Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ (RDS21+) sets the main objectives of regional development for the period 2021-2027. It identifies thematic areas that require a territory-specific approach and defines different interventions to be implemented in different territorial contexts to promote competitiveness, reduce regional disparities, and find solutions promoting sustainable development of the territory. The strategy also serves as a guide for regional governments in developing regional development strategies. Besides, The Ministry of Regional Development - National Coordination Authority (MoRD-NCA) commenced the preparation of the Partnership Agreement in the 2021-2027 programming period between the European Commission and Czechia which lays out the country’s cohesion policy investment strategy worth EUR 21.4 billion for the period 2021-2027.

This partially integrated governance framework supporting the Czech FDI-SME ecosystem might require the implementation of whole-of-government coordination strategies, communication channels and information exchange mechanisms to address the possible emergence of policy silos (which we don’t currently observe) and reduce the risks of information asymmetries leading to higher transaction costs.

4.2.3. Strengthening agencies responsible for implementation of national policies at regional and local level

Government action at local levels is important for tailoring policies to local needs, especially in less developed regions where closer proximity to foreign investors enhances the effectiveness of investment promotion agencies. The presence and active engagement of government institutions at the regional and local levels can be a factor in ensuring that policy is tailored to local socio-economic characteristics and needs. For example, research on EU countries shows that closer proximity to foreign investors’ operations makes investment promotion agencies (IPAs) more effective in pursuing their function and better addressing investors’ needs, in particular in less developed regions where information asymmetries and institutional failures are more widespread (Crescenzi, Di Cataldo and Giua, 2019[6]).

The main national implementing agencies supporting the FDI-SME ecosystem in Czechia are present at regional level. Both CzechInvest and the Business and Innovation Agency (API) operate own subnational offices in all the 13 Territorial Level 3 (TL3) Czech regions outside the capital. In addition, CzechInvest and CzechTrade jointly operate 13 contact points for entrepreneurs in regions (regional export consultants), providing training and consulting services to local companies. In 2019, these regional export consultants organised over 1 900 meetings with Czech companies in regions (CzechTrade, 2020[7]). The National Development Bank (NRB) has branches in the regional capital cities of South Moravia, Hradec Králové, Moravia-Silesia, Pilsen, and an office in the capital of South Bohemia (České Budějovice) (NRB, 2023[5]).

Evidence from interviews conducted with institutional representatives highlight considerable collaboration among subnational offices of national institutions operating in the same regions or municipalities. The South Moravia region provides a good example of such good practices in inter‑institutional collaboration and subnational level (see Chapter 6). Collaboration mostly takes places through informal channels, facilitated by personal linkages and connection and the sharing of office spaces.

However, in the pursuit of fostering robust local innovation ecosystems, it is crucial to strengthen collaboration among regional innovation centres (which are typically established by regional governments and have no direct link to national ministries), national implementing agencies, and ministries. Existing regional innovation centers, one-stop-shops, and business consultation centres could be empowered. These centers possess firsthand knowledge of local dynamics, understand the unique challenges faced by businesses, and have the capacity to drive innovation. Increased coordination between implementing agencies operating at the local level (CzechTrade, CzechInvest, API) and other regional stakeholders could facilitate dialoguealignment of strategies, identification of synergies, and addressing specific regional needs become possible. For example, it would help to reduce regional disparities and address the challenges that weaker regions face regarding mobilising public and private actors in support of local business ecosystems. It may also help ensure interconnection between national, regional, and local delivery of FDI, SME and innovation services and strike the right balance between national and local priorities.

To enhance the effectiveness of such collaboration, bridging the gap between national policy-making and regional policy implementation is imperative. Subnational branches of government implementing agencies require resources to increase coordination at the local level, develop local initiatives, tailor their services to the needs of their local areas, build their own contacts and brands, and lead partnerships with regional and local authorities that may lack the capacity to support the local entrepreneurial ecosystem. Greater tailoring of national policies at the subnational level should be combined with due coordination among national agencies operating locally through regular meetings and consultations on an ad hoc basis. Furthermore, it is essential for national policymakers to engage actively with regional innovation centres to overcome communication barriers and facilitate information exchange. National ministries could benefit from this engagement by gathering feedback from regional innovation centres about the business needs “on the ground”, while also providing centres with necessary capacity building. Better coordination and rationalisation of the FDI-SME governance and institutional setting at the national level could help prevent inconsistent support quality and avoid fragmentation or overlapping in services delivery at the regional and local levels (see next section) (OECD, 2022[3]).

4.2.4. Czechia has a complex multilevel governance system

The Czech subnational system structure is the foundation for local governance and policymaking. Czechia has a two-tier subnational system, with 6 254 municipalities (obce) and 14 regions (kraje – 13 regions and the City of Prague). The capital city of Prague has a unique dual status as both a municipality and a region. The municipal level includes municipalities, towns (mesto) and 25 statutory cities (statutarni mesto) – i.e., having a special status that enables them to establish districts at the sub-municipal level with their own mayor, council, and assembly (OECD-UCLG, 2016[8]).

Municipalities and regions exercise both autonomous competences as well as competences delegated by the central level (delegated powers). Municipalities can be categorised based on the scope of their delegated powers. Indeed, while autonomous competences are the same for all municipalities, delegated powers vary depending on the municipalities’ size and capacity. At the upper level are municipalities with “extended powers”, that fulfil the largest set of delegated administrative functions. At the intermediate level are municipalities with “authorised municipal authority”, performing delegated functions on a smaller scale. At the lower level, municipalities have only “basic delegated powers” (OECD, 2023[9]; OECD-UCLG, 2016[8]).

Regions are responsible for overarching policies and municipalities for service delivery which are key for SMEs operating across the country and for FDI attraction. Municipal competences include education (pre-elementary, primary, and lower secondary education), agriculture, housing, primary health care, social care services, local roads and public transport, water and waste management (“extended powers” only) (OECD-UCLG, 2016[8]). The range of purely local competences assigned to municipalities by the law is relatively small, meaning that most of their responsibilities are shared with the central or regional governments (OECD, 2023[9]).Regions also have autonomous and delegated competences. They are responsible for regional economic development and planning, environmental protection, both very relevant for SMEs based in the region and for attraction of foreign investment. This extends to another important factor in the development of FDI-SME ecosystems, which is the infrastructure management, in particular regional roads and transport. In some instances, regions and municipalities bear responsibilities for the same policy areas; however, their competencies are divided between the funding of programmes and overarching policy in the case of regions, and the delivery of services in the case of municipalities (OECD, 2023[9]).

While the complex governance system allows for adaptability, it often results in coordination challenges which might hamper business development. The system often results in overlaps in the allocation of responsibilities and calls for strong coordination among levels of government. Given the high number of local self‑governments, this co-ordination represents a significant challenge for Czechia. For example, when it comes to implementing delegated responsibilities, the national government tends to coordinate only with municipalities with “extended powers” – i.e., with a broader range of delegated competences (OECD, 2023[9]). A 2020 study of Czech local government strategies during the COVID-19 crisis reveals the absence of effective co‑ordination mechanisms between the central government and municipal actors, which complicates the transmission and implementation of policies to support SME activities and to attract FDI. The study identified that the complicated and bureaucratic administrative setting does not allow key decision‑makers at the national and local levels to quickly share information and take informed decisions to devise the optimal response in a short period of time. This inconsistency can affect the overall quality or outcomes of FDI-SME policies because it can lead to discrepancies in implementation across regions and municipalities (Plaček, Špaček and Ochrana, 2020[10]).

4.2.5. … and a highly fragmented territorial administration that has implications for the implementation of effective FDI-SME policies.

Czechia has one of the most fragmented territorial organisations in the OECD. There is large number of very small municipalities in terms of area and population. In 2020, the average municipal size was the smallest among OECD countries (1 710 inhabitants per municipality on average), well below the OECD average of 10 250 and the EU average of 5 960. While the median size of Czech municipalities is 442 inhabitants, 96% of municipalities had fewer than 5 000 inhabitants and almost 90% had fewer than 2 000 inhabitants in 2021. The average municipal area is also the lowest in the OECD: on average, Czech municipalities have an area of 13 km2 compared to 234 km2 on average across the OECD (OECD, 2023[9]; OECD, 2021[11]).

Czech regions are also small by international standards. The average size of Czech regions is 2.5 smaller than the average size of the EU28 NUTS 2 regions in terms of inhabitants and 4 times smaller in terms of area (Ministry of Interior of the Czech Republic, 2018[12]). Only 3 of the 14 regions are large enough to be qualified as NUTS 2 regions for EU regional funding purposes (Prague, Central Bohemian and Moravian-Silesian region). The remaining 11 regions are NUTS 3 regions which, for statistical purposes, are joined to form 5 additional NUTS 2 regions (OECD, 2023[9]).

The administrative fragmentation, and particularly the very high number of small municipalities, undermines policy co-ordination between the national and subnational levels and affect the cost efficiency of public service delivery for SMEs and foreign investors. Most Czech municipalities are too small to ensure a cost-effective provision of public services. Many of them are remote and sparsely populated, increasing even more the cost of public service provision (OECD, 2023[9]), which in turn might make such municipalities less attractive for entrepreneurs and foreign investors.

This can lead to inefficiencies in the implementation of FDI-SME policies. Even though the majority of business regulations are established at the national level, the fragmentation of territorial administration in Czechia can create a complex regulatory environment with different rules and regulations in different regions, making it difficult for foreign investors and SMEs to navigate the business environment and comply with all relevant regulations. Different administrative units may interpret and implement policies differently, leading to inconsistencies and creating uncertainty for businesses, which may deter foreign investment. Businesses, particularly SMEs, may face an increased administrative burden due to the need to comply with different regulations in different regions, which can divert resources away from core business activities and hinder growth. The complexities and inconsistencies associated with a fragmented territorial administration can act as a barrier to market entry for foreign investors and SMEs, limiting the number of new businesses entering the market and hindering competition. The uncertainties and complexities associated with a fragmented territorial administration can impact investment decisions, with foreign investors potentially choosing to invest in regions with less administrative fragmentation due to the perceived lower risk and ease of doing business. Strategies aimed at addressing municipal fragmentation in Czechia, supplemented with examples of governance efforts from other countries for inter-municipal cooperation, are elaborated in Chapter 6.

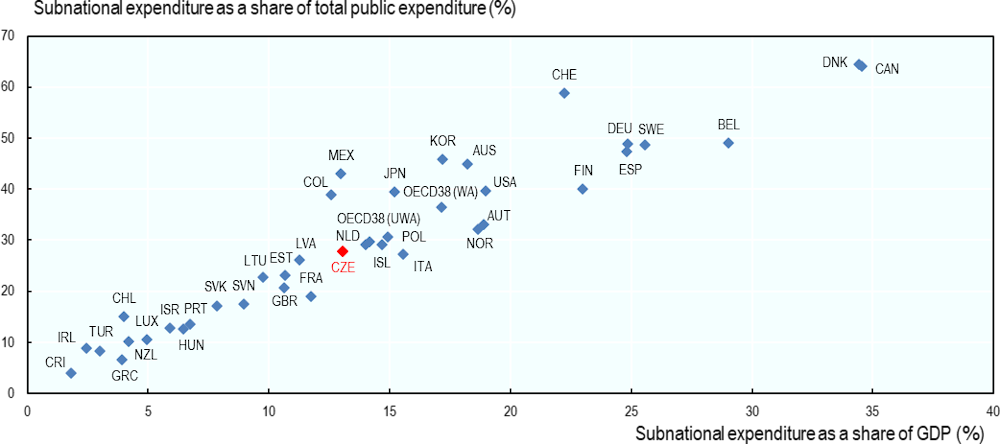

4.2.6. Regional and municipal governments’ resources are limited

Insufficient financial resources relative to the extensive responsibilities of regional and municipal governments in supporting FDI-SME ecosystems may create a financing gap. The relatively broad competencies of regional and municipal governments in supporting FDI-SME ecosystems does not appear to be always matched with sufficient financial resources. This may result in a financing gap in the implementation and delivery of policies. Czechia remains a relatively centralised country in terms of public expenditure. In 2019, about 30% of total public expenditure was carried out by subnational governments compared to an OECD average of 40% (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. The Czech subnational government expenditure is below OECD average

Copy link to Figure 4.4. The Czech subnational government expenditure is below OECD averageSubnational government expenditure as a % of GDP and total public expenditure, 2020

Source: OECD regional statistics database (accessed on 19 October 2023), https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en

4.2.7. Better co-ordination among levels of governance could foster efficiency in the delivery of public services

Czechia has already taken initiative to reform its multi-level governance system. The current public governance reform agenda, known as the Public Administration Reform (PAR) Strategy: Client-oriented Public Administration 2030, contemplates the definition of a new system of municipal delegated powers, aiming to concentrate those in the hands of the municipalities with sufficient personnel and expertise to effectively exercise them. The objective of this reform is to improve the quality of services delivery and reduce the administrative burden on the smallest municipalities (OECD, 2023[9]).

Vertical coordination across different tiers of government remains challenging, particularly due to territorial fragmentation. Territorial fragmentation, and particularly the very high number and small size of municipalities, challenges vertical co-ordination across national, regional, and local governments. This fragmentation also affects regional-municipal coordination, with the degree of challenge varying across the country due to differing numbers of municipalities per region (OECD, 2023[9]). Considering these challenges, the National Development Bank (NRB) emerges as an effective model for delivering public services. On subnational level it works closely with regional branches of CzechInvest and collaborates with all commercial banks in the Czech market, providing guarantees to SMEs when needed. The Bank support the Ministry of Industry and Trade in the design of programmes and on identifying the priorities to be pursued, leveraging its direct experience dealing with SMEs. This coordination supports both SMEs and the public sector and can significantly contribute to the development of effective FDI-SME linkage policies in Czechia.

Enhancing inter-municipal co-operation could set common territorial development objectives to plan and implement projects with a long-term horizon and at the relevant scale. According to a recent OECD review of Czech public administration, co-operation between municipalities in Czechia primarily revolves around specific investment projects or service delivery where they perceive mutual benefits, with a noticeable absence of a holistic territorial development strategy for cooperation and planning (OECD, 2023[9]). Transitioning from project-based cooperation to a comprehensive, long-term territorial development approach among Czech municipalities could significantly enhance FDI-SME policies. This shift would allow for strategic planning and implementation of larger-scale projects with a long-term horizon, making the country more attractive for foreign investors and providing a supportive environment for SMEs. It could also lead to more efficient resource utilisation and policy consistency across municipalities. By pooling resources, municipalities could provide better support services for SMEs and foreign investors, such as setting up business support centres or providing joint training programs. Joint efforts can lead to the development of shared infrastructure, such as industrial parks or innovation hubs, which can attract FDI and provide opportunities for SMEs.

To ensure the success of multi-level governance reforms in Czechia, it is crucial to build consensus and buy-in from different stakeholders. Czechia has a history of strong centralisation – before the Velvet Revolution of 1989, power was concentrated at the central level. After 1989, Czechia transitioned from a centralised system towards a decentralised system of self‑governing subnational governments. Since the change in the political regime, Czechia has undergone several transformations to its territorial administrative structure. The decentralisation efforts of the last years are thus viewed as a step forward in ensuring proximity with citizens and for policy implementation that responds better to local needs. As is the case in several OECD countries, recentralising some responsibilities is generally met with pushback from municipal associations and representatives. It is therefore crucial to accompany multi-level governance reforms with the appropriate consultations, negotiations and communication efforts to gain support from local actors and society (OECD, 2023[9]; OECD, 2017[13]; OECD, 2017[14]).

4.2.8. There is a need to continue building subnational government capacities for the successful development and implementation of FDI-SME policies

Acute skill gaps and lack of administrative capacity in smaller subnational units add to the challenges in delivering quality services at local level. Subnational governments in Czechia face an acute gap in adequate skills and administrative capacity. This is particularly true at the local level where, in addition to the skill gaps, they confront difficulties attracting talent (OECD, 2023[9]). Foreign investors look for regions with strong administrative capacity and a skilled workforce. SMEs often rely on local government support in various forms, including regulatory assistance, access to financing, and business development services. Improved capacities can lead to more effective policy implementation, make the region more attractive to foreign investors, enhance support for SMEs, and facilitate the creation of successful FDI-SME linkages.

4.3. Policy coordination across institutions and fields of government

Copy link to 4.3. Policy coordination across institutions and fields of governmentEffective public intervention in support of FDI-SME ecosystems requires the alignment of objectives and priorities across different policy areas. This often calls for coordination among a number of government institutions dealing with FDI promotion, SME development, innovation, and regional development. Institutional coordination can be achieved through different instruments and present multiple challenges, which are presented in more details in Box 4.3.

Czechia's performance in inter-institutional coordination is below the standard of the leading OECD economies. The country ranks 35th out of 41 economies in the inter‑ministerial coordination sub-indicator in the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) 2022. The SGI report on inter-ministerial coordination provides further insight indicating that while the Office of the Government of Czechia serves as the central body of state administration, its primary role revolves around administrative functions rather than offering direct oversight for proposals put forth by line ministries (BertelsmannStiftung, 2022[15]).

The recent Public Governance Review done by the OECD in cooperation with the Czech government (OECD, 2023[9]) reports that the lack of strategic steering capacities and alignment from the centre have led to the multiplication of strategies and an absence of consistency and implementation across policies. Strategic decisions, regulations and policies are also insufficiently based on evidence. This calls for strengthening the strategic coordination of the Government Office and boosting analytical capacities across public administration (OECD, 2023[16]).

Box 4.3. Policy coordination: principles, instruments, and benchmarking

Copy link to Box 4.3. Policy coordination: principles, instruments, and benchmarkingInstruments of co-ordination can be based on regulation, incentives, norms, and information sharing. They can be top-down and rely upon the authority of a lead actor or bottom-up and emergent (Peters, 2018[17]). They include (OECD, 2012[18]):

National strategies and action plans typically involve wide consultation and deliberation, provide diagnostic overviews of what the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of an SME, innovation, and local ecosystem could be, and set a shared vision of the goals pursued.

Closely related, policy evaluations and reviews are a source of strategic intelligence, and a means for promoting greater co-ordination.

Dedicated agencies or ministries assume the leadership of the national policy agenda in some policy domains (e.g., FDI/SME/innovation/regional) and often have responsibility of coordination. At the same time, inter-agency joint programming can facilitate co-ordination and other aspects of governance as agencies share agenda and action.

The centre of government (CoG), e.g., the President's or Prime Minister's Office, can bridge interests and bureaucratic boundaries. High-level policy councils can also deal with aspects of policy coordination although they often have variable roles and composition across countries.

Finally, informal channels of communication between officials or job circulation (of civil servants, but also experts and stakeholders) can play a role and suggest a relatively well-developed culture of inter-agency trust and communication.

Although coordination is a fundamental and longstanding problem for public administration and policy, there is still no standardised method for approaching related issues, and much of the success or failure of attempts to coordinate appears to depend upon context (Peters, 2018[17]). Coordination approaches and instruments need to be matched to circumstances, so does the need to coordinate across countries and policy areas. Some policy domains may work well with minimal attempts to coordinate with others, but others may require substantial policy integration and coordination. Likewise, some political systems may emphasise coordination and governance more strongly than others (Hayward and Wright, 2002[19]).

4.3.1. High-level strategic coordination remains challenging

Czechia should ensure horizontal policy coordination on FDI-SME policy

A strong network of high-level government bodies can help ensure horizontal policy coordination across ministries and other public institutions operating in the field of FDI-SME support. In the Slovak Republic, for instance, several advisory councils are in place bringing together the Prime Minister’s office, line ministries, implementing agencies, and regional and local governments to identify priority areas where cross-ministerial policy planning and decision-making is necessary (OECD, 2022[3]).

The recent Strategy to support SMEs in Czechia for the period 2021-2027 provides substantial evidence of efforts aimed at enhancing inter-ministerial coordination, including by establishing an inter-Ministerial Management and Coordination Committee. Its design was based on an inter-ministerial consultation process aimed at identifying existing policy measures and budgetary resources to be reallocated and coordinated under the strategy’s umbrella. The strategy provides indeed an overarching framework for the implementation of over 100 policies specifically targeted towards SMEs. This involves multiple competent ministries and agencies, given the interdisciplinary nature of the strategy. To facilitate effective coordination, the strategy outlines the establishment of a Management and Coordination Committee. This committee serves as the principal body responsible for managing, coordinating, and monitoring the implementation of the strategy. It convenes at least annually to discuss the current progress and status of the various measures, propose changes to implementation plans within each key area as necessary, and suggest amendments to the strategy itself. In the framework of the strategy’s implementation, steering and technical inter-ministerial meetings are organised monthly. Informal coordination practices also play a key role ensuring the coordination of the different institutional actors involved.

As for FDI policy, Czechia has implemented a mechanism of foreign investment screening which involves high-level coordination between Ministry of Industry and Trade, national security institutions, and other involved regulators. The screening includes both a preliminary mandatory application for permission of investment and ex officio screening proceedings initiated by the Ministry of Industry and Trade. This is in line with the Act No. 34/2021 Coll., on the Screening of Foreign Investments (the “FDI Act”) which applies to foreign investments. The FDI Act aims to protect the security of Czechia and its public and internal order. To make a risk assessment of investments, the authority assesses the nature of the business sectors in which the investments are made, as well as the target companies and foreign investors themselves. In addition to the Ministry, which is the competent administrative body and the contact point for cooperation between EU Member States, formal screening is consulted on with the intelligence services, the Police of the Czech Republic and other security services. Depending on the type of transaction, regulators such as the Czech National Bank, the Czech Telecommunications Office and the Energy Regulatory Office also submit their opinions. This coordination mechanism allows for effective information gathering and exchange, and direct competencies and capacity to react to the actual situation without delay.

In the area of research, development, and innovation (R&D&I), the Council for Research, Development and Innovation (CRDI) is the main advisory body to the Government of the Czech Republic. It is a horizontal policy coordination and a strategic intelligence body which oversees the preparation of important R&D&I policy documents, such as national strategies, annual analysis, and assessments of the Czech R&D&I system. It also formulates proposals regarding state budgetary allocations in R&D&I. Among other, the Council is in charge of overseeing and validating the allocation of R&D funds through the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TA CR). It holds meetings with similar EU Member States’ councils, administrates the R&D&I information system, and nominates the Czech Science Foundation and the Czech Technology Agency Management Board Members (EC-OECD, 2023[20]). In fulfilling its tasks, the CRDI cooperates with central administration bodies and institutions dealing with R&D&I. The Council draws up long-term fundamental trends and schemes for the R&D&I in Czechia through its advisory bodies, which have been established as professional commissions involved in respective trends of R&D&I (EC-OECD, 2023[20]).

The proliferation of strategic documents makes their implementation and coherence more challenging

In Czechia, several strategic documents have been adopted in recent years to articulate priorities related to strengthening FDI and SME linkages. National strategies and action plans can be important instruments for policy coordination as they are crosscutting in nature, but they often require a whole-of-government approach to ensure their effective implementation.

These frameworks outlined in Table 4.2 guided by a mix of overarching goals and specific objectives, emphasise the importance of digital transformation, research and development, and the integration of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence. The strategies are implemented through a collaboration of government bodies, with a significant role played by the Council for Research, Development, and Innovation (CRDI) and the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Notably, the Industry 4.0 Strategy focuses on enhancing competitiveness through global supply chain participation and efficient manufacturing. The strategies collectively address a wide range of areas including skills development, international market access, and low-carbon economy initiatives.

Table 4.2. National strategic frameworks supporting the FDI-SME ecosystem in Czechia

Copy link to Table 4.2. National strategic frameworks supporting the FDI-SME ecosystem in Czechia|

Strategic framework |

Timeframe |

Description |

Responsible institutions |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Innovation |

Innovation Strategy: The country for the Future |

2019-2030 |

It sets the goal for science, research, and innovation to become an absolute priority in the country, focusing on knowledge-based production, technology solutions and services. The strategy, together with other pillars, addresses the digital competences and skills development in education, for the labour force and information and communication technology (ICT) experts. |

Prime Minister’s office through the Council for Research, Development and Innovation (CRDI) |

|

National Policy of Research, Development and Innovation 2021+ |

2021-… |

An overarching strategic document for advancing all components of research, development, and innovation. The document also helps fulfil certain criteria of the basic conditions to be able to draw funding from European Union funds in the 2021–2027 programming period. Its aim is to establish a strategically managed and effectively financed RDI system in Czechia, to achieve higher development of R&D&I activities in businesses and in the public sector, and to achieve higher openness and attractivity of Czechia for international R&D. |

Council for Research, Development and Innovation (CRDI) |

|

|

National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation |

2021-2027 |

It is a strategic document ensuring effective directing of European, national, regional, and private resources for the support of oriented and applied R&D and innovation. It aims to enhance innovation performance of companies, to enhance quality of public research, to improve availability of qualified people for research, development, and innovation and to increase utilisation of new technologies and digitalisation. The essential role of RIS3 is to systematically mobilize researchers, innovators, entrepreneurs, representatives of universities and the public sphere to discover new opportunities and to cooperate with each other. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

|

Industry 4.0 Strategy |

2017-… |

A national initiative aiming to maintain and enhance the competitiveness of Czechia with three main objectives: to enhance the ability of Czech companies to participate in global supply chains; to implement Industry 4.0 principles to achieve more efficient manufacturing (i.e. faster, cheaper and resource effective production); and to enhance cooperation among R&D and industry associations, universities and the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic for the development of software solutions, patents, production lines and export know-how. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

|

National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy |

2019-2035 |

Under the conception Digital Economy and Society, this strategy aims to promote digital transformation facilitated by the AI-based solutions. It introduces measures to foster top academic and enterprise AI research and development and promotes deployment of AI technologies with the emphasis on SMEs and start-ups. Measures include building digital innovation hubs, supporting start-ups and attracting smart investments as well as introducing tools to promote investment in innovative projects and automation, especially in relation to SMEs. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

|

Digital Economy and Society |

2018-… |

It is a key and cross-cutting strategy for the digitization of the whole society. It promotes positive aspects of societal and economic changes associated with the digital revolution and minimizes negative impacts (e.g., on the labour market). The main ambition is to ensure the long-term competitiveness and overall prosperity of Czechia by developing this area. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

|

SME & entrepreneurship |

Strategy to support SMEs in the Czech Republic |

2021-2027 |

The strategy identifies 107 measures pursuing the common goal of improving the productivity and competitiveness of Czech SMEs. Key areas addressed in the document include the business environment; access to finance; access to international markets; workforce, skills, and education; research, development, and innovation; the digitalization; low-carbon economy and resource efficiency. |

Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

Regional development |

Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ |

2021-2027 |

The strategy aims to ensure tailor-made support for regions, reflect the territorial dimension in sectoral policies, develop strategic planning and management based on functional regions, strengthen cooperation among actors in the territory, improve coordination of strategic and spatial planning, develop smart solutions and improving work with regional development data. |

Ministry of Regional Development |

|

Investment promotion |

National Brownfield Regeneration Strategy |

2019-2024 |

The objective of this strategy is to create a suitable environment for rapid and effective implementation of brownfield investment projects. The strategy aims at the revitalization of sites, expansion of the offer for businesses, improvement of the environment in all aspects and achievement of effective use of previously neglected sites. The goal is to turn those sites into high-quality, built-up areas and landscapes while respecting the cultural, historical, economic, ecological, and social standpoints. |

CzechInvest |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023) and national strategic documents.

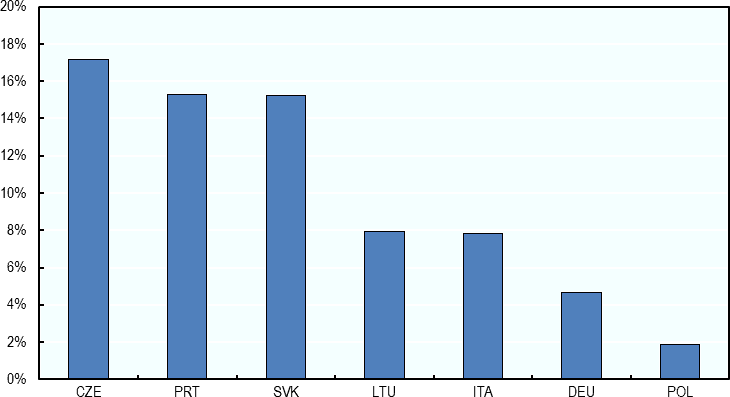

However, the number of different strategic documents might make policy coordination more complex. Compared with other countries analysed, Czechia has the highest share of policies related to FDI-SMEs (17%) (Figure 4.5). However, these are high-level national strategies, rather than concrete implementation programmes. And Czechia has more such documents than peer countries, heightening the risk of making it more difficult to ensure overall policy coherence among the strategic objectives identified, and to monitor their actual implementation (OECD, 2023[9]).

Figure 4.5. Czechia has numerous national strategies and plans in FDI-SME support compared to peer countries

Copy link to Figure 4.5. Czechia has numerous national strategies and plans in FDI-SME support compared to peer countries% of governance frameworks in total policies mapped per country, 2023

Source: Experimental indicator based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023)

Diverse strategic documents have been recently adopted in the area or innovation policy. Among the most relevant, the National Research and Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialisation, implemented by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, sets up sectorial and thematic priorities over the EU programming period 2021-27.

Among the strategic frameworks, the Industry 4.0 Strategy stands out as a national initiative strategically designed to bolster Czechia's global competitiveness, with a strong focus on SMEs. With objectives ranging from efficient manufacturing to fostering collaboration among research and industry entities, this initiative underscores the nation's commitment to staying at the forefront of technological progress. The National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy outlines measures to promote digital transformation facilitated by AI-based solutions, with a keen focus on supporting SMEs and start-ups. The interconnectedness of these frameworks, addressing areas such as skills development, international market access, and low-carbon initiatives, reflects Czechia's comprehensive and forward-looking strategy to create an innovative and thriving business environment.

The investment promotion area represents a notable exception to the trend, as Czechia does not have a national investment strategy. Investment policy considerations are incorporated in broader strategic documents. A national brownfield strategy to attract FDI in former industrial areas is implemented by CzechInvest, in collaboration with the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry for Regional Development, Ministry of the Environment and Ministry of Agriculture.

Investment promotion strategic goals are currently interwoven to a certain extent within the Smart Specialisation Strategy and in the Innovation Strategy. A well-articulated national strategy and action plan can help guiding specific measures, ensuring they align with a country’s policy priorities and implementation capacity. While in Czechia there isn’t such a document, various strategies like the Smart Specialisation Strategy and Innovation Strategy encompass elements of a strategic framework for investment promotion. It's important to note that these strategies do mention the FDI element, but they do not explicitly establish it as a strategic objective for FDI promotion activities. This integration of FDI could benefit from a more explicit strategic focus.

Investment promotion plans can help productivity growth, innovation, regional development, job creation, and transitions towards a digital and low-carbon economy. A strategic document could help tailor efforts to attract investors aligned with sustainable development goals, showcasing the country's openness to FDI. A complementary short-term Action Plan, linked to the national strategy, could provide a more focused and operational tool. This plan could outline specific actions and policy initiatives to be undertaken over a defined timeframe with dedicated financial resource allocations, promoting policy coordination and effective collaboration with relevant government bodies and stakeholders.

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) are integral components of successful investment promotion. Implementing a comprehensive M&E system, including a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system, enables effective tracking and analysis of IPA activities. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) could for example identify types of firms and investments benefiting from public support and the sustainability-related impacts of supported investments. The use of qualitative evaluation methodologies, feedback processes, and surveys can further enhance understanding and adjustment of services, providing valuable insights for policy advocacy and decision-making.

The Netherlands' approach exemplifies the importance of collaboration and coordination in investment promotion Box 4.4. The Invest in Holland Network's joint efforts align with the concept of a National Plan on Investment Promotion, demonstrating how different entities can work together to attract and support foreign investors. The Netherlands' success highlights the significance of a well-organised, inter-agency framework, efficient resource allocation, and prioritisation to enhance the overall impact of investment promotion strategies. The Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency (NFIA) effectively employs a collaborative and coordinated approach, as seen through the Invest in Holland Network, comprising 14 organisations, to attract foreign direct investments (FDI).

Box 4.4. Coordination on investment promotion and facilitation: The Invest in Holland Network

Copy link to Box 4.4. Coordination on investment promotion and facilitation: The Invest in Holland NetworkThe Netherlands Foreign Investment Agency (NFIA) operates as a department in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy while its activities take place under the umbrella of the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO). In 2021, there were 28 NFIA offices abroad, including own premises in countries of strategic importance for FDI attraction, as well as agency representatives located across the Dutch embassies and consular offices. Although the agency has no subnational offices, it manages the Invest in Holland Network, which comprises 14 organisations, including regional development agencies, city administrations, and other non-profit entities. The network aims to provide a continuum of support services to foreign investors and connect them with the right public and private sector partners depending on the type and location of their investments. The Invest in Holland Strategy 2020-2025 describes the policy areas for which the network operates jointly while indicating that each partner is free to undertake complementary investment promotion activities in line with their own priorities. In the period 2015-2019, approximately 1800 investment projects were successfully completed with the help of the Invest in Holland Network, with a total investment value of EUR 12 billion and having created or maintained approximately 57.000 jobs.

The network is coordinated through the National Acquisition Platform (NAP), which is chaired by the NFIA Commissioner, and includes representatives of each organisation. Members meet once per quarter to discuss on the basis of joint short-term activity plans, take stock of progress in achieving FDI targets and evaluate the implementation of the Invest in Holland Strategy. Throughout the year members benefit from networking and knowledge sharing events as well as brainstorming meetings on how “working together” can be further simplified. To ensure consistency in the quality of services provided to foreign investors, the Invest in Holland Academy has been established to provide courses and seminars for new employees that join one of the 14 organisations as well as for more senior members and investment promotion staff located in the Dutch diplomatic missions abroad.

Investment prioritisation takes place through inter-agency Focus Teams that work on promoting investments in high-priority activities (ICT, Agri food, Life sciences and health, sustainable energy). Focus Teams hold regular meetings with companies and research institutions operating in various industries with the aim to identify new investment opportunities. They are also responsible for monitoring the business climate and bringing opportunities and threats to the attention of policymakers. For instance, in 2019, the Focus Team ICT, with NFIA and 5 regional partners, developed various value propositions, drew up target lists and visited conferences and events to generate new investment leads. Thanks to these efforts, a total of eight high-quality ICT investment projects were attracted in 2019.

The increased attention that investment generation activities receive in the Netherlands is reflected in the annual resources dedicated for that purpose. Roughly 70% of the NFIA resources are spent to find and guide potential initial investments, 20% of them are spent to find and guide potential follow-up investments (i.e., maintaining and expanding activities), 5% is spent for the role of the NFIA in the Invest in Holland network (i.e., cooperation between regional partners) and 5% to collect feedback from foreign companies on opportunities for improvement of the business climate.

Source: OECD based on Evaluatie van de NFIA 2010-2018 (NFIA, 2020[21]) https://open.overheid.nl/repository/ronl-2342ca2e-27ee-4da1-a407-ea24af4d63ad/1/pdf/bijlage-evaluatie-van-de-nfia.pdf and Invest in Holland Strategie 2020-2025 (NFIA, 2020[22]) https://open.overheid.nl/repository/ronl-1b3f0055-62a6-4757-80e7-7f32236d8f43/1/pdf/bijlage-invest-in-holland-strategie.pdf

4.3.2. Inter-institutional collaboration is not frequent and takes place either informally or in a centralised manner through line ministries

While the Ministry of Industry and Trade actively coordinates and collaborates with various stakeholders in the area of SME and FDI policies….

The Ministry of Industry and Trade holds a core mandate in both the SME and FDI policy domains, which presents an opportunity for enhanced coordination in these areas. For SME policy, the Ministry has actively pursued the objective of enhancing coordination among the key actors involved in SME policy governance (ministries, agencies, research organisations, institutions, and banks). The objective being to offer a comprehensive system of assistance to support SMEs across all stages of the business cycle, spanning from innovation and development assistance. The special focus is on firms that produce and export higher value-added goods and services and participate in global value chains, meaning SMEs which could be part of FDI-SME ecosystems (Anwar, Lopez and Chua, 2019[23]).

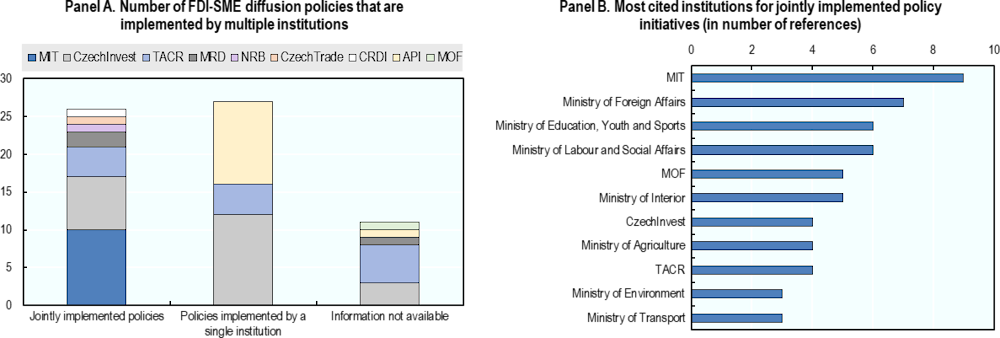

Furthermore, the FDI-SME policy mapping reveals coordination arrangements between the Ministry of Industry and Trade and various state agencies and financial institutions, including CzechInvest, CzechTrade, the National Development Bank, and the Czech Export Bank. A relatively low number of FDI-SME diffusion policies (40%) show a degree of coordination among different institutions (Figure 4.6, Panel A). This includes initiatives and programmes that are designed and implemented jointly by agencies and ministries, or strategies and action plans that require a whole-of-government approach to be executed. Among the institutions that are most cited in the implementation of joint programmes, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Finance, and the main implementing agencies (CzechInvest, TACR) stand out given the crucial role they play in supporting FDI and SME policies (Figure 4.6, Panel B). The Ministry of Industry and Trade itself is responsible for the design and implementation of 10 initiatives which are all implemented in partnership with other institutions. Nevertheless, the implementation of business support tools is fragmented across numerous ministries and national agencies with oversight in various areas.

Figure 4.6. Collaborative policy design and implementation in Czechia

Copy link to Figure 4.6. Collaborative policy design and implementation in Czechia

Note: MIT: Ministry of Industry and Trade; TACR: The Technology Agency of the Czech Republic; MRD: Ministry for Regional Development; NRB: The Czech-Moravian Guarantee and Development Bank; CRDI: Council for Research, Development and Innovation; API: Business and Innovation Agency; MOF: Ministry of Finance.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2023).

… there is a need for formalised intergovernmental coordination between national and subnational governments

However, insights from the EC/OECD Survey on Policies enabling FDI spillovers to domestic SMEs point to potential improvements in policy coordination between national and subnational governments in the design of policies. Multilevel coordination in the design of overarching national strategies appears to be lacking, while national strategies present interesting opportunities for inter-agency dialogue and collaboration involving regional and sub-national actors (OECD, 2021[24]).

4.4. Evaluation of policy impact and stakeholders engagement

Copy link to 4.4. Evaluation of policy impact and stakeholders engagement4.4.1. In Czechia more than half of FDI-SME diffusion policy initiatives have integrated M&E and Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) systematically

Evaluating the impact of public policy interventions on the economy can help governments identify gaps and take corrective action to enhance their effectiveness. The adoption of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks by government institutions is particularly important for policy initiatives targeting FDI-SME diffusion, which often requires public action from across different policy areas and therefore enhanced scrutiny to ensure that policy action achieves the expected results.

The monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework of policies in Czechia needs enhancement. As highlighted in the recent OECD Public Governance Review conducted in cooperation with the Czech government, in Czechia, strategic decisions, regulations, and policies are insufficiently based on evidence. This calls for boosting analytical capacities across public administration.