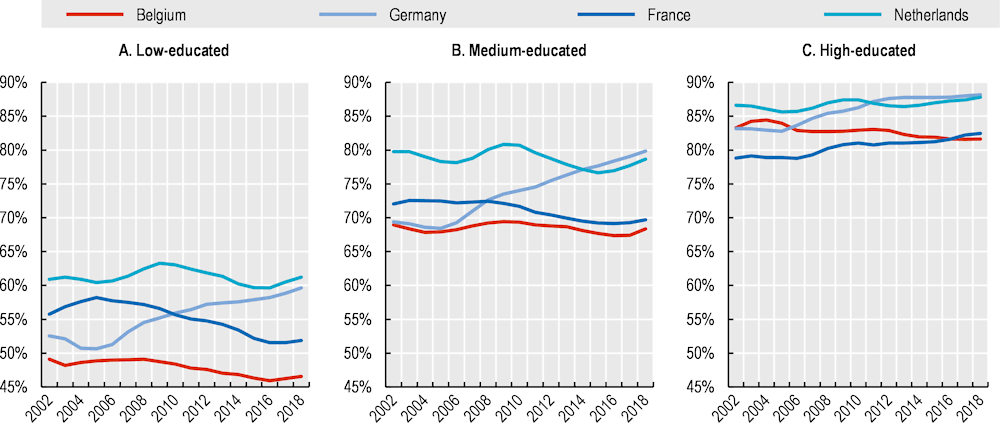

The low-educated represent a shrinking share of the labour force in Belgium, but this share is larger than in neighbouring countries. In Belgium, the share of low-educated in the population has dropped from 41% in 1998 to 22% in 2018. However, the share of low-educated in Belgium remains higher than in neighbouring countries: 20% in both the Netherlands and France, and 14% in Germany. In addition, important regional differences remain. The share of low-educated in the workforce is considerably higher in the Brussels-Capital Region (28%) and Wallonia (25%) than in Flanders (19%).

The composition of the low-educated has changed significantly over time. In 1998, 50% of the low‑educated were women, 15% were migrants and 28% were aged 55‑64. In 2018, 47% were women, 33% were migrants, and 36% were aged 55‑64. Overall, the low-educated in Belgium are now more likely to be male and, in particular, older and from an immigrant background. These changes mean that policies aimed at promoting better labour market outcomes among the low-educated need to take account of their changing demographic characteristics. Different groups face different challenges.

Migrants represent a particularly vulnerable group who will need special attention. Belgium’s share of migrants (20% of the population aged 20‑64) is similar to Germany’s (21%) but considerably higher than that of France and the Netherlands (14‑15%). Moreover, migrants in Belgium tend to be less qualified than in neighbouring countries: 43% of migrants in Belgium from outside the EU have no (formally recognised) secondary qualification, compared to only 32% in the Netherlands, 37% in France and 38% in Germany.

There is significant skills mismatch in Belgium, and most new job opportunities will require at least an upper secondary qualification. Before the COVID‑19 crisis hit, the Belgian labour market showed signs of tightness, despite the low (and falling) level of employment among the low-educated. This reflects an important imbalance in skills demand and supply. In Belgium as a whole, there are 30 employed persons with higher education for every unemployed person with higher education. Among the low‑educated, there are just under seven employed persons for every unemployed person. An analysis of the existing shortage occupation lists indicates that less than 1% require low-educated workers. The vast majority (nearly two thirds) require an upper secondary qualification. Upskilling would therefore offer significantly better employment opportunities to many low-educated workers in Belgium.

Boosting investments in initial education will need to be accompanied by measures to encourage lifelong learning. Ensuring that all young people leave school with the right skills to quickly find a good job is essential. Too many young people still struggle to find a foothold in the labour market due to poor educational attainment. However, efforts will be needed to ensure that people continue learning even after they have left school. This is an area where Belgium underperforms by international standards, particularly among the low-educated. Participation in adult learning in Belgium (70%) is similar to the EU‑28 average, and below participation in France (79%) and the Netherlands (87%). Among low-educated workers, participation in adult learning in Belgium (54%) is below the EU‑28 average (60%).

Activation measures need to be better targeted and give more weight to training. Belgium spends a relatively large share of its GDP on active labour market policies to get the unemployed back into work. In 2017, Belgium dedicated 0.88% of GDP to active labour market policies (i.e. excluding spending on passive measures such as out-of-work income maintenance and support, as well as early retirement). This is higher than in France (0.87%), Germany (0.65%) and the Netherlands (0.64%). However, Belgium’s spending on active policies is heavily skewed towards measures that are more likely to suffer from large deadweight losses (e.g. employment incentives). Another difference between Belgium and other countries is that it spends comparatively less on training: just 0.14% of GDP, compared to double that in France (0.28%). Yet training can improve employability and could also help address the important skills mismatch that exists in Belgium today.