This chapter takes a forward-looking view of the labour market for low‑educated workers in Belgium, focusing on both job quantity and quality, as well as on issues of skills gaps and mismatches. The number of jobs occupied by low-educated workers in Belgium is forecast to decline, as is their employment rate. In the future, the remaining jobs for low-educated workers will be primarily in elementary occupations, but the industry composition of those jobs will continue to shift towards services. The shift towards service industries is likely to bring lower job quality for low‑educated workers.

The Future for Low-Educated Workers in Belgium

3. The future for low-educated workers in Belgium

Abstract

This chapter takes a forward-looking view of what the labour market for low-educated workers might look like in Belgium in the absence of any new policy interventions. The chapter focuses on the projected quantity of jobs for the low-educated, as well as on the issue of skills gaps and mismatches. The chapter then examines what projected shifts in the employment distribution of the low-educated across industries might imply for the quality of their jobs in the future.

Continuing a long-prevailing trend, the low-educated are expected to make up a decreasing share of the labour force over the next 10 years. However, the number of jobs occupied by low-educated workers is forecast to decline at an even faster pace, meaning that their employment rate is likely to decline even further (while in neighbouring countries Germany and the Netherlands, it is expected to rise). The shortage of jobs for the low-educated occurs in a context of considerable labour market tightness overall (at least before the COVID‑19 crisis hit). In the future, the remaining jobs for low-educated workers will be primarily in elementary occupations, but the industry composition of those jobs will continue to shift towards services. The shift towards service industries is likely to bring lower job quality for low-educated workers.

3.1. The share of low-educated workers will continue to fall, but so will their employment rate

The share of the labour force who are low-educated is expected to shrink as younger cohorts entering the labour market have increasingly more education. Over the past 30 years, each successive young cohort has tended to get more education than previous cohorts (Chapter 1). The net result for almost all European OECD countries is a shrinking share of the labour force composed of low-educated workers in the absence of any other policy interventions.

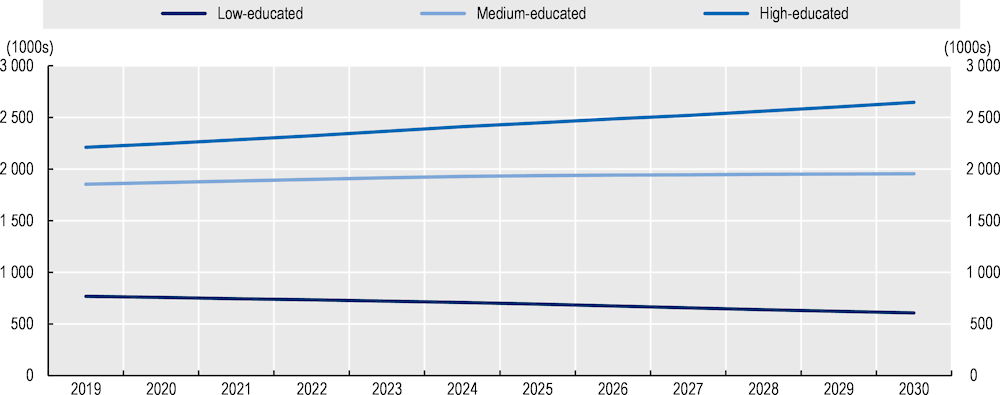

While the number of low-educated in the population is expected to fall in Belgium, so is the number of jobs held by low-educated workers. Between 2019 and 2030, Cedefop1 estimates that the number of jobs held by low-educated workers in Belgium will fall from 770 000 to 610 000 – i.e. by 21% (Figure 3.1). By contrast, the number of jobs held by medium- and high-educated individuals is forecast to grow by 100 000 (+5%) and 430 000 (+20%), respectively.

Figure 3.1. The number of jobs for the low-educated is expected to fall

Note: Employment refers to the number of people in work (headcount) or the number of occupied jobs in the economy. Employed is defined as someone who worked at least one hour in the reference period for financial or non-financial reward.

Source: Cedefop Skills Forecast.

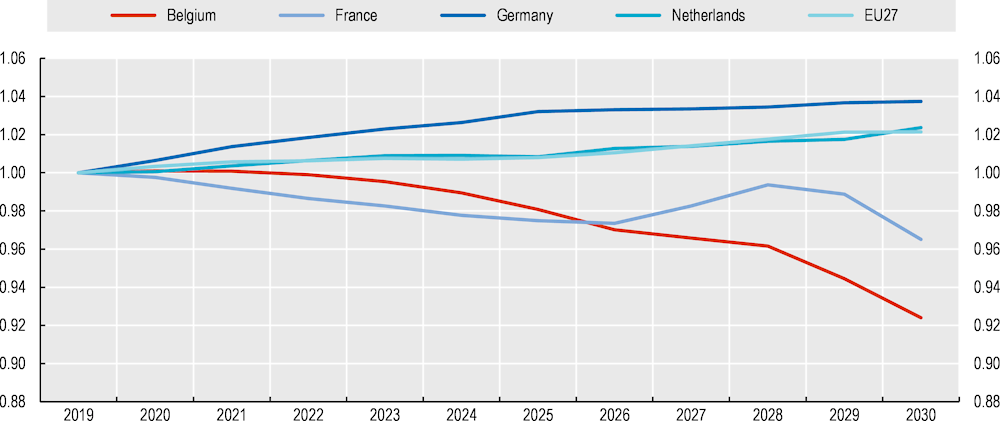

The employment rate for the low-educated is also expected to fall in Belgium, but this is not an inevitable consequence of a shrinking share of low-educated workers. In neighbouring countries France, Germany and the Netherlands, the number of jobs occupied by the low-educated is also expected to decline, however the employment rate for the low-educated is only expected to fall in Belgium and in France (and considerably more so in Belgium than in France). By 2030, the employment rate among low-educated in Belgium could be 7 percentage points lower than it is now (Figure 3.2). In France, it is expected to be 3 percentage points lower. By contrast, in the Netherlands and Germany, it could be 2 and 3 percentage points higher, respectively.

Figure 3.2. The employment rate for the low-educated in Belgium is expected to fall

Note: The forecast of the employment rate is obtained by combining the Cedefop forecast of the labour force and the Cedefop forecast of employment trends. These two forecasts use different data sources and are not necessarily compatible. The employment forecast uses national accounts data and is on a workplace basis. These data can include multiple jobholding and cross-border commuting. The labour force forecast is based on labour force surveys and is on a residence basis. Due to these differences in frame, the employment forecast is not constrained by the labour force forecast. There can therefore be instances where the forecast for employment is higher than the forecast for total labour supply, especially in the longer term. Cedefop advises against estimating future employment rates based on comparing demand and supply. These caveats should be borne in mind when interpreting the figure.

Source: OECD calculations based on Cedefop Skills Forecast.

3.2. Imbalances are emerging in the Belgian labour market between the skills needed and the skills supplied

The falling demand for low-educated workers documented in the previous sub-section already translates into skills mismatches in the Belgian labour market which are worsening over time. Chapter 2 has documented large (and worsening) differences in employment and unemployment between individuals with different educational attainment, which is one indicator that low-educated workers are in over-supply relative to demand.

Previous OECD research has also documented skills imbalances in the Belgian labour market. For example, the OECD Skills for Jobs indicators show that almost seven out of ten jobs facing skills shortages in Belgium require high skills, compared to just five out of ten in the OECD on average (OECD, 2018[1]). Similarly, Belgium has a high share of under-qualification2 compared to most other OECD countries: 22.4% of workers in Belgium are estimated to be under-qualified for the job that they are doing, compared to 18.4% across the OECD on average (OECD, 2017[2]).

This sub-section presents some additional evidence on this (growing) mismatch between the demand for, and supply of low-educated workers in Belgium. In particular, it shows that the worsening labour market outcomes of the low-educated occurred in the context of an increasingly tight labour market overall (prior to the COVID‑19 crisis), and that there are strong regional and sectoral dimensions to the imbalance in demand and supply for low-educated workers. The final sub-section indicates that upskilling could offer a partial solution to the imbalance in labour demand and supply of low-educated workers given that many of the emerging shortage occupations require medium-level skills.

3.2.1. Despite dire job prospects for the low-educated, the labour market showed signs of tightness before the COVID‑19 crisis

Before the COVID‑19 crisis, the Belgian labour market showed signs of tightness even as the low-educated increasingly struggled on the labour market. Since the global financial crisis, the job vacancy rate in Belgium (i.e. the ratio of job vacancies to the number of occupied posts + job vacancies) had been steadily increasing from 1.5 in 2010 to 3.5 in 2019. This ratio is high by international standards (2.3 in the EU‑28 on average), which suggests that employers in Belgium found it difficult to fill positions, despite the high level of non-employment among the low-educated. This indicates a significant level of mismatch in the labour market. The job vacancy rate in Belgium was similar to that in the Netherlands (3.3) and in Germany (3.3) (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Prior to the COVID‑19 crisis, the Belgian labour market showed signs of tightness

Job vacancy rate, 2010‑19

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EU‑28 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

|

Belgium |

1.5 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

Netherlands |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

3.3 |

|

Germany |

1.6 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

Note: Job vacancy rate = number of job vacancies / (number of occupied posts + number of job vacancies).

Source: Eurostat.

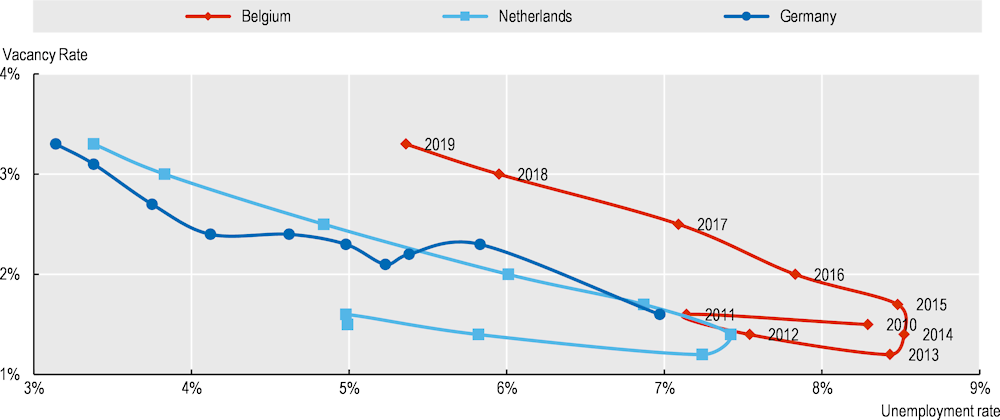

Movements in the Beveridge curve confirm this increasing tightness of the labour market, but also indicate that labour market efficiency is higher in Germany and the Netherlands than in Belgium. The Beveridge curve relates the vacancy rate to the unemployment rate and serves as a measure of the efficiency with which labour markets match available workers to available jobs. In all three countries, the vacancy rate has increased since the global financial crisis as the unemployment rate has dropped (Figure 3.3). It is also clear that for a similar vacancy rate, the unemployment rate is considerably higher in Belgium than in Germany and the Netherlands, which indicates that the matching process in Belgium is far less efficient that in neighbouring countries.

Figure 3.3. Labour market matching is less efficient in Belgium than in Germany and the Netherlands

Source: Eurostat Job Vacancy Statistics for the vacancy rate. OECD Labour Force Statistics for the unemployment rate.

3.2.2. The matching challenge has a regional (and sector) dimension

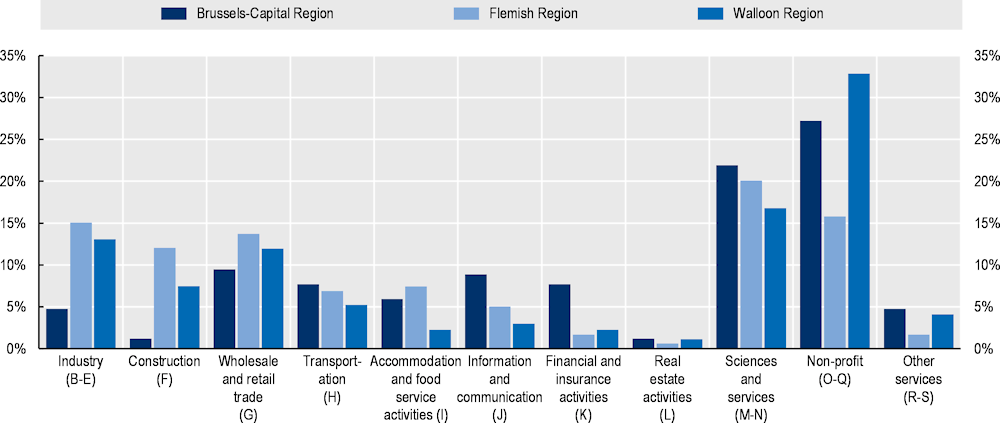

Vacancy data confirm a strong regional element to the matching challenge in Belgium. Overall, there were around 140 000 vacancies in Belgium at the end of 2019, nearly 70% of which were in Flanders, just over 10% in the Brussels-Capital Region, and nearly 20% in Wallonia. By comparison, 24% of the unemployed are based in Flanders, 33% in the Brussels-Capital Region and 43% in Wallonia. These differences across regions are confirmed by the job vacancy rate, which is much higher in Flanders (3.9% in 2019) than in Wallonia (2.7%). There are also important differences across regions in terms of the composition of vacancies, with a much larger share of vacancies in Flanders being in industry, construction, and retail and wholesale trade. In Wallonia, a third of vacancies are in the non-profit sector (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. The distribution of vacancies across industries varies by region

Note: Shares add to 100% by region. Letters in parentheses refer to NACE classification.

Source: Statbel, https://statbel.fgov.be/en.

3.2.3. Shortage occupations lists reveal many opportunities for workers with a secondary qualification

Each year, the regional public employment services in Belgium publish a shortage occupation list.3 In 2020, the list of shortage occupations was much longer in Flanders (218 occupations) than in the Brussels‑Capital Region (108 occupations) and Wallonia (72 occupations), again highlighting differences across regions in employment opportunities.

Very few of those shortage occupations (less than 1%) require low-educated workers. The vast majority require an upper secondary qualification (nearly two thirds) – although, in the Brussels-Capital Region, the share of shortage occupations that require a tertiary qualification is much higher than in the other regions (43% versus around 22% in both Flanders and Wallonia).

Upskilling would offer better employment opportunities to many low-educated workers. There are many training courses available for the unemployed who are interested in pursuing a career in one of these shortage occupations. In many cases, individuals can continue receiving unemployment benefits while they undertake such courses. Evidence for the Brussels-Capital Region suggests that vocational training programmes that are directly related to a shortage occupation are much more likely to result in employment (18 percentage points) than vocational education programmes overall (view Brussels, 2018[3]).

3.3. Forecasts indicate that low-educated workers will increasingly move into lower-pay industries

The projected decline in employment for low-educated workers is likely to include some reshuffling of workers across occupations and industries. Younger workers will find opportunities in occupations or industries, which may differ from those where earlier cohorts found work. Mid-career workers who are displaced may need to switch industries or occupations to continue their careers. This section examines which occupations and industries are forecast to employ low-educated workers in the next 10 years, and what this implies for future job quality for low-educated workers.

3.3.1. The low-educated are forecast to remain in elementary occupations

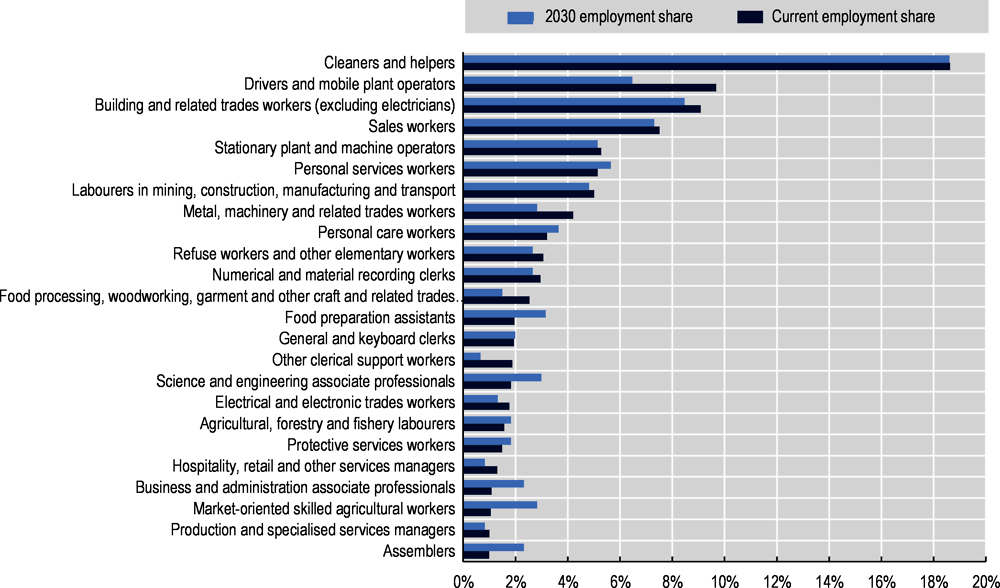

The low-educated in Belgium are concentrated in elementary service occupations. In 2018, the occupation employing the highest share of the low-educated is cleaners and helpers with 19% (Figure 3.5). The next two occupations employing the highest share of low-educated workers are drivers and mobile plant operators (10%) and building trades workers (9%). Combined, these three occupations employ over one third of low-educated workers in Belgium.

Figure 3.5. Employment in Belgium is projected to grow in occupations that do not employ low‑educated workers

Note: Only occupations with at least 1% employment share are shown.

Source: 2018 occupation shares from European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). 2030 occupation shares derived from Cedefop.

The distribution of employment across occupations will remain concentrated in elementary occupations. Cleaners and helpers are forecast to remain the occupation employing the most low-educated workers (19%). Building trades are projected to employ the second most low-educated workers (9%), and sales occupations are projected to grow into the occupation employing the third-most low-educated workers (7%). Drivers and mobile plant operators are expected to experience the largest decline in overall employment share. The current and continued reliance on cleaning occupations for low-educated employment may pose problems for workers going forward as these occupations are increasingly outsourced to service firms (see Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Domestic outsourcing risks diminishing job quality for many jobs performed by the low‑educated

Domestic outsourcing, or the subcontracting of jobs to outside firms, is a trend that is by no means new, but continues to affect workers in OECD countries including the low-educated. The defining feature of domestic outsourcing is that the subcontracted work was, or could be, done within the boundaries of the lead firm (i.e. the firm outsourcing the job). The result is often jobs moving from high-wage to lower‑wage industries.

Classic examples of domestic outsourcing concern the work of janitorial, cafeteria, and security services. Workers in these support occupations perform labour within the physical boundaries of a lead firm, often on a regular and ongoing basis, but a secondary firm is often their legal employer.

Domestic outsourcing is not limited to low-wage service jobs. Professional services firms also provide high‑skill labour such as information technology, accounting, human resources and legal services to lead firms. Crucially, the lead firm chooses to contract with a secondary firm (or even an own-account worker) to provide these services instead of employing the workers directly in-house, as many companies did in the past.

Firms may outsource the work of support roles and even core functions for a variety of reasons. First, firms may want to more flexibly control their labour demand for non-core occupations. This will result in greater specialisation within firms and possibly to greater productivity. Second, firms may subcontract work to reduce wage and benefit costs. This is particularly true in high-wage industries or unionised firms. Although this is an active and nascent area of research, studies from the United States and Germany find that outsourced workers in low-skill support occupations earn less and are subject to lower job quality compared to similar workers employed in the lead firm (Dube and Kaplan, 2010[4]; Freedman and Kosová, 2014[5]; Ji and Weil, 2015[6]; Goldschmidt and Schmieder, 2017[7]).

Documenting the rise of domestic outsourcing often focuses on the professional and business services (PBS) industry (ISIC rev 4. “M/N”). This industry is unique in that it mostly provides services to other firms rather than end customers. It is also bifurcated by skill providing both high-skill technical or legal services, but also janitorial, security, and general employment services to firms. While far from perfect, PBS provides the best cross-country comparison for the rise of domestic outsourcing, which has a heavy concentration of industries shown to be engaged in outsourcing relationships (Weil, 2019[8]).

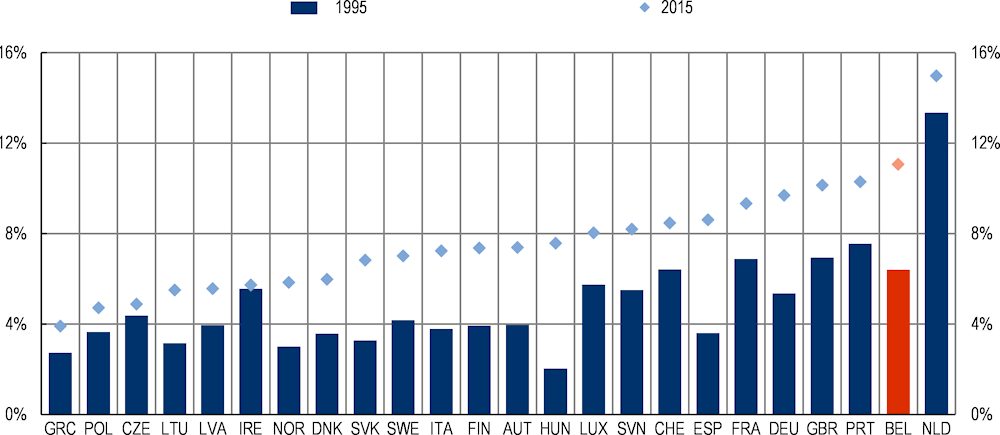

Compared to other European OECD countries, Belgium has a high and growing share of outsourced workers. Part of this is likely due to the implementation of the service cheque programme initiated in 2008 (see Chapter 4), but the rise is similar to that observed in many other OECD countries. In 2015, 11% of employment in services was performed by workers in Administrative and Support Service activities (ISIC rev4 “N”), which is nearly double the share in 1995 (Figure 3.6). This industry comprises firms providing lower-skilled services to other firms, and its growth is outpacing growth in services overall. Only the Netherlands has a higher share of service employment (15%) in administrative and support services than Belgium.

Figure 3.6. Domestic outsourcing is growing in most European OECD countries

Note: STAN data for category D77T82 “Administrative and support service activities [N]” divided by D45T99 “Total services”. Closest year to 1995 available is 1998 for Ireland, and 2001 for Poland.

Source: OECD Structural Analysis Database (STAN), http://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/stanstructuralanalysisdatabase.htm.

3.3.2. Manufacturing is expected to experience the biggest loss of low-educated workers

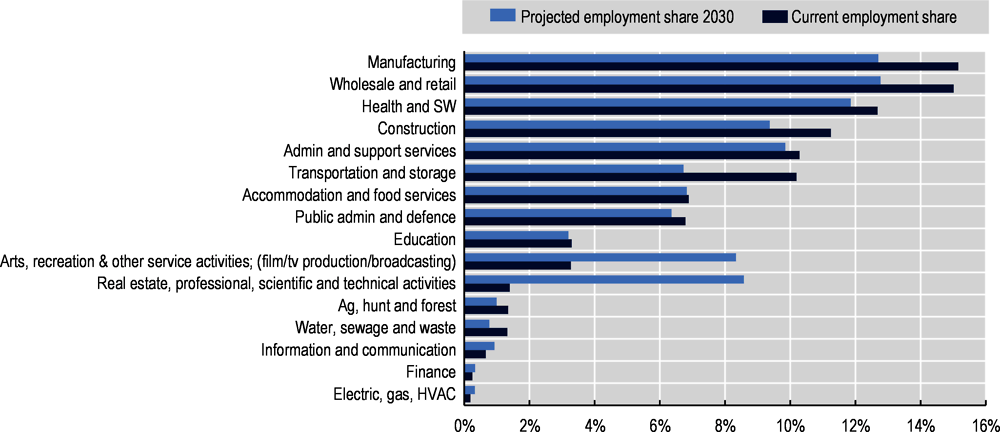

Low-educated workers are currently most likely to be employed in manufacturing as well as in wholesale and retail trade. Figure 3.7 shows the distribution of employment of low-educated workers across industries in 2018 and the projected employment distribution in 2030. The four industries most likely to employ low‑educated workers in Belgium in 2018 are Manufacturing (15.2%); Wholesale and Retail (15.0%); Health and Social Work (12.7%) and Construction (11.3%). The least likely to employ low-educated workers are Finance; Electric, Gas, and Heating; and Information and Communication.

Industries with a significant shrinking share of the low-educated population are principally the industries which now employ the most low-educated workers: Wholesale and Retail as well as Manufacturing. By 2030, the distribution of low-educated workers in Belgium is expected to shift away from Manufacturing and towards high- and low value-added services. The biggest shift will be towards Arts, Recreation and Other Services as well as towards Real Estate, Professional, Scientific and Technical activities. The latter is somewhat surprising, as professional services tends mostly high-educated workers. It may be related to the general rise in firm-to-firm service industries (see Box 3.1).

It has sometimes been argued that the growth of the circular economy the greening will lead to significant job creation, including for the low-skilled. While OECD work confirms that green growth policies will create new jobs, particularly in sectors with low emission intensities, it will also result in job destruction in emission-intensive sectors. The overall impact of decarbonisation policies on employment is therefore expected to be positive, but small. In addition, low-skilled workers will generally be more affected by these transitions than other categories of workers (Chateau, Bibas and Lanzi, 2018[9]).

Figure 3.7. The share of the low-educated working in manufacturing is expected to fall

Note: Industries with less than 1% employment share not shown.

Source: 2018 industry shares from European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). 2030 industry shares derived from Cedefop.

The loss of employment share in manufacturing is a long-term trend

Manufacturing has traditionally been a high-wage industry employing a large share of low-educated workers. Economists have long recognised that even after adjusting for worker characteristics, industry wage differentials persist and confer higher pay to otherwise similar workers who find employment in high‑wage industries (Krueger and Summers, 1988[10]; Gibbons and Katz, 1992[11]). Manufacturing is perhaps the best example of a high value-added industry that consistently delivers higher pay, and has also traditionally employed a large share of workers without a tertiary education (Helper, Krueger and Wial, 2012[12]; OECD, 2020[13]).

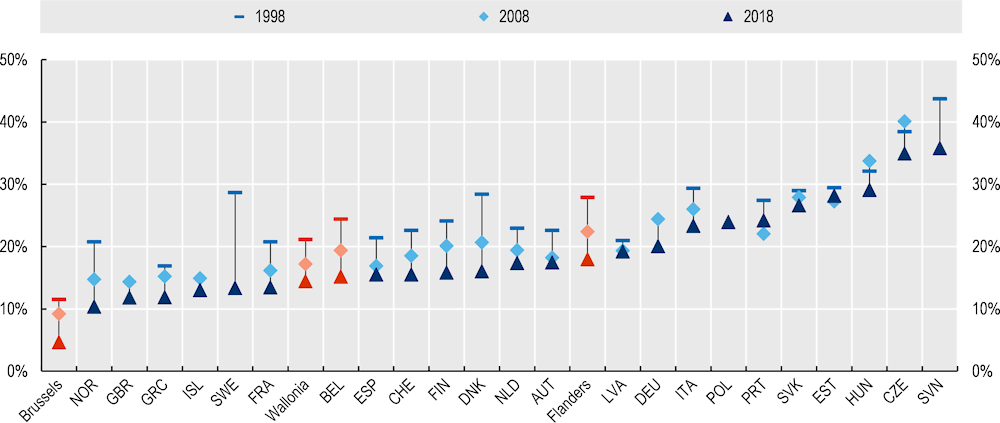

For low-educated workers, the shift away from manufacturing has been a long and steady trend. Belgium’s share of low-educated workers employed in manufacturing (15.2%) is lower than in neighbouring countries Germany (20.4%) and the Netherlands (17.1%), but higher than in France (13.5%). For all countries involved, the share has declined over the past 10 years (Figure 3.8). The share of low-educated workers employed in manufacturing in Belgium has been declining for the past 20 years, falling from 24.4% in 1998. This is a larger percentage point decline than in either the Netherlands or France.4

Figure 3.8. The share of low-educated workers employed in manufacturing has experienced a slow, steady decline

Note: Data cover all employed persons aged 20‑64 with a low-education (ISCED 0‑2).

Source : European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

In Belgium, Flanders has the largest share of low-educated workers employed in manufacturing, but it has also experienced the largest percentage point decline. In 2018, the share of low-educated workers employed in manufacturing in Flanders was 17.9%, a higher share than in the Netherlands, but lower than in Germany. Wallonia and the Brussels-Capital Region had lower shares of low-educated workers in manufacturing: 14.4% and 4.6%, respectively. Although Flanders retains the highest share of the low‑educated employed in manufacturing, its share has fallen the most over the past 20 years. The share in Flanders fell from 27.9% in 1998 to 17.9% in 2018, compared to Wallonia where the share fell from 21.1% to 14.4% over the same period. The fall in the Brussels-Capital Region was similar to Wallonia (6.9 percentage points). In 1998, 11.5% of the low-educated in the Brussels-Capital Region were employed in manufacturing where today manufacturing employment has mostly disappeared. The shift away from manufacturing is by itself concerning for the labour market outcomes of low-educated workers, but changes within manufacturing are another merging trend to watch (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Posted workers are an emerging trend in some industries employing a high share of low-educated workers

The freedom of firms to provide services across borders within the EU was established in 1959, and it is one of the cornerstones of the European Union. Under this principle, firms established in one member state are allowed to post their workers to another member state to perform a work mission for a limited duration of time (12 months since the revised version of the Posted Workers Directive adopted in 2018). Sending firms do not have to establish themselves in the country where the work mission is performed, nor are they required to hire workers in this country. Crucially, workers posted from the sending country are exempt from all social security contributions and labour taxes in the country of work, and stay affiliated to the social security regime in the country where the sending firm is established. These provisions can make labour much cheaper in countries with high social security contributions. They are also exempt from labour market rules in the destination country with the exception of the minimum wage, minimum paid leave, and legal maximum duration of work. Starting in 2020, posted workers will have to adhere to all mandatory laws of remuneration in the host country.

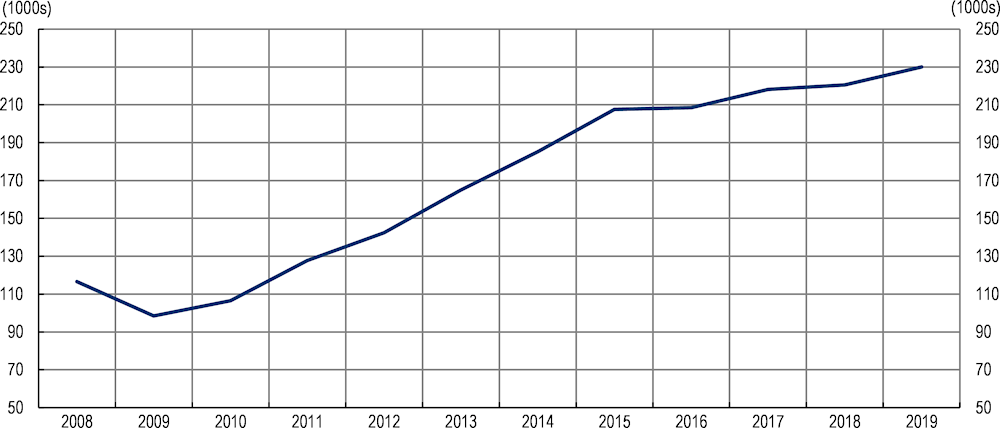

Belgium is one of the main destination countries for posted workers. Since 2007, Belgium collects detailed administrative data on the number of workers posted by foreign companies to its territory. From 2008 to 2019, the number of unique posted workers to Belgium doubled from approximately 100 000 workers in 2009 to over 230 000 in 2019 (Figure 3.9). These numbers somewhat understate the penetration of posted workers into the Belgian labour market as workers can be posted for multiple assignments (so the number of assignments could be greater than the number of workers). In 2019, the number of posting missions to Belgium reached 800 000 performed by 230 000 unique posted workers. Posted workers represent a substantial share of Belgian domestic labour force, as they account for roughly 3% of the working age population and 4.5% of total domestic employment in 2019.1

Posting is concentrated in a few sectors in Belgium. Most posted workers are employed in construction and specific sub-sectors of manufacturing, such as metal works and electrical installation, which tend to employ, and pay high wages to low-educated workers. The effect of posted workers on domestic workers employed in industries with high shares of posted employment remains an open research question. Specifically, it is unclear whether foreign posted workers are complements to domestic workers, which would possibly spur demand for domestic workers, or whether, conversely, posted workers are substitutes for domestic workers, and depress domestic employment as well as wages and working conditions. The latter would be due to the various loopholes in the original rules around posting workers.

Figure 3.9. Belgium is experiencing a continuous increase in posted workers

Note: Number of unique workers posted each year to Belgium recorded by the social security administration over the period 2008‑19. A unique worker can be posted several times over the period.

Source: Muñoz (forthcoming[14]), “Workers Across Borders: Equity-Efficiency Trade-offs in Mobility Policies”.

1. Comparing the number of posted workers to the number of domestic employed gives a first approximation of domestic labour market exposure to posting. This approach is however imperfect as it does not translate posting employment in full time equivalents. For a discussion of this issue see De Wispelaere, Chakkar and Struyven, (2020[15]).

3.3.3. Job quality for low-educated workers is likely to decline slightly

The gradual reallocation of low-educated workers across industries will have implications also for the quality of the jobs that they will be able to obtain. Job quality in some industries is higher than in others. This section estimates the possible implications of the reallocation of low-educated workers across industries for job quality. Using a regression framework to adjust for worker characteristics, industry wage premiums are estimated for low-educated workers in Belgium as well as the probability of being in non‑standard work.5 On the assumption that job quality within industries remains constant over time, the projected reallocation of workers across industries would imply a modest decrease in wages and an increase in the incidence of non-standard work for low-educated workers.

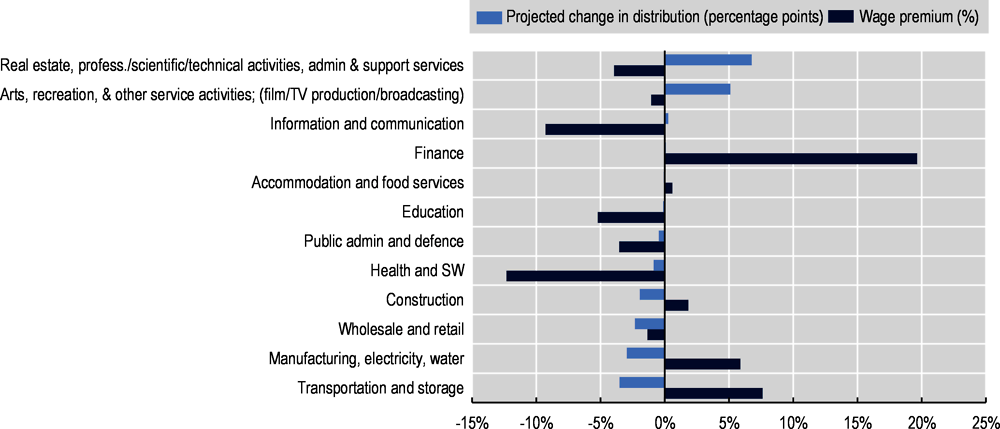

Structural changes are likely to lead to lower pay for low-educated workers

Low-educated workers in Belgium are projected to move into lower wage industries. Figure 3.10 shows the estimated industry wage premium and the projected percentage point change in the industry distribution of low-wage workers. Real Estate and Professional Services and Arts and Entertainment are expected to see the largest increases in the share of low-educated workers. These sectors have negative wage-premiums of ‑3.9% and ‑1.0%, respectively, implying that, for a given set of characteristics, low‑educated workers are paid less in those industries than in others.

Figure 3.10. Employment for the low-educated in Belgium is projected to shift towards lower-wage industries

Note: Wage premiums expressed as the percentage difference from the average wage among low-educated, full-time workers in Belgium pooling years 2014‑18. The wage premium regression adjusts raw inter-industry wage differences to account for demographic differences of workers across industries.

Source: 2018 industry shares from European Union Labour Force Survey. Long-run growth forecasts from Cedefop. Wage premiums estimated from EU-SILC.

By contrast, the share of low-educated workers in high-wage industries is expected to fall. Manufacturing currently employs the largest share of low-educated workers and it is projected to employ the second largest share in 2030, being overtaken by wholesale and retail trade. Manufacturing is also projected to lose the largest share of low-educated workers. Manufacturing has one of the highest estimated wage premiums for low-educated workers (5.9%). The shift away from manufacturing therefore will have negative consequences for the pay of low-educated workers. Holding industry wage-premiums fixed, the projected change in the employment distribution of low-educated workers will result in a 1.4% decline in wages for the low-educated by 2030.

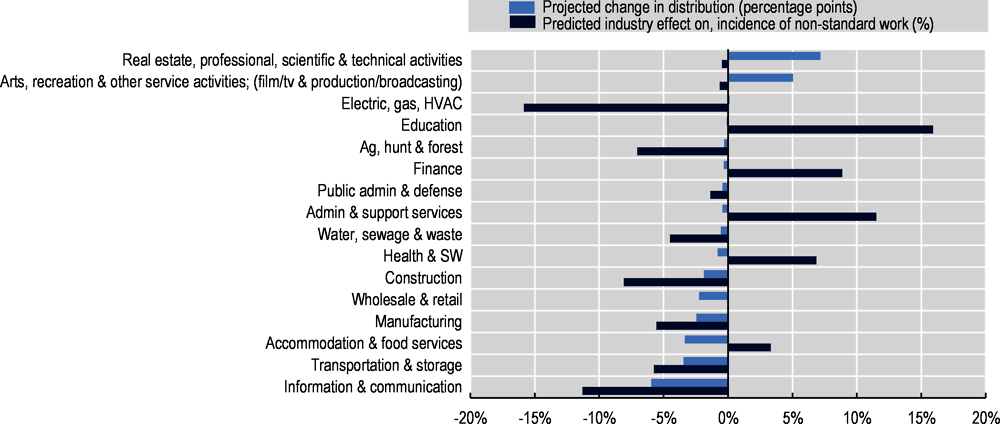

The incidence of non-standard work is expected to increase slightly

Just as with wages, the shifting employment distribution for low-educated workers will result in a modest increase in non-standard work. The total change in the projected share of non-standard work is small – a 0.4 percentage point increase or 1.2%. The underlying dynamics are more subtle as both the industries gaining the most low-educated workers and those losing the most (same as in Figure 3.7), are industries less likely to employ non-standard workers. However, manufacturing and information and communication are particularly unlikely to use non-standard work (shrinking industries), while the industries gaining employment shares are only marginally less likely to employ non-standard workers on average (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11. Low-educated employment is also projected to shift towards industries who employ more non-standard working arrangements

Note: Non-standard work includes workers on fixed-term contracts or part-time hours. Incidence of non-standard work expressed as percentage difference from average rate of non-standard work among low-educated, full-time workers in Belgium pooling years 2014‑18. Incidence of non‑standard work regression adjusted to account for demographic differences of workers across industries. Projected change in the employment distribution is the percentage point difference in industry shares between 2018 and the projected 2030 distribution.

Source: 2018 industry shares and incidence of non-standard work from European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). Long-run growth forecasts from Cedefop.

References

[9] Chateau, J., R. Bibas and E. Lanzi (2018), “Impacts of Green Growth Policies on Labour Markets and Wage Income Distribution: A General Equilibrium Application to Climate and Energy Policies”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 137, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ea3696f4-en.

[15] De Wispelaere, F., S. Chakkar and L. Struyven (2020), Détachement entrant et sortant dans les statistiques belges sur le marché du travail. Avec un focus sur la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale., HIVA-KU Leuven , Leuven, https://lirias.kuleuven.be/2958874?limo=0 (accessed on 26 August 2020).

[4] Dube, A. and E. Kaplan (2010), “Does Outsourcing Reduce Wages in the Low-Wage Service Occupations? Evidence from Janitors and Guards”, ILRReview, Vol. 63/2, pp. 287-306, http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/ilrreview (accessed on 7 February 2019).

[5] Freedman, M. and R. Kosová (2014), “Agency and compensation: Evidence from the hotel industry”, Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, Vol. 30/1, pp. 72-103, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ews027.

[11] Gibbons, R. and L. Katz (1992), “Does Unmeasured Ability Explain Inter-Industry Wage Differentials”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 59/3, p. 515, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2297862.

[7] Goldschmidt, D. and J. Schmieder (2017), “The rise of domestic outsourcing and the evolution of the german wage structure”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 132/3, pp. 1165-1217, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx008.

[12] Helper, S., T. Krueger and H. Wial (2012), Why Does Manufacturing Matter? Which Manufacturing Matters? A Policy Framework, Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

[6] Ji, M. and D. Weil (2015), “The Impact of Franchising on Labor Standards Compliance”, ILR Review, Vol. 68/5, pp. 977-1006, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0019793915586384.

[10] Krueger, A. and L. Summers (1988), “Efficiency Wages and the Inter-Industry Wage Structure”, Econometrica, Vol. 56/2, p. 259, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1911072.

[14] Muñoz, M. (forthcoming), “Workers Across Borders: Equity-Efficiency Trade-offs in Mobility Policies”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[13] OECD (2020), “What is happening to middle-skill workers?”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c9d28c24-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Skills for Jobs: Belgium country note, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dotstat.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=77595 (accessed on 8 June 2020).

[2] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Skills for Jobs Indicators, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277878-en.

[3] view Brussels (2018), De beroepsinschakeling van werkzoekenden na een opleiding voor een knelpuntberoep 2018, https://www.actiris.brussels/media/rttnrzgr/de-beroepsinschakeling-van-werkzoekenden-na-een-opleiding-voor-een-knelpuntberoep-2018-h-920C3533.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2020).

[8] Weil, D. (2019), “Understanding the Present and Future of Work in the Fissured Workplace Context”, RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol. 5/5, p. 147, http://dx.doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2019.5.5.08.

Notes

← 1. Cedefop is one of the EU’s decentralised agencies, supporting development of European vocational education and training (VET) policies. As part of their work, they also release various labour force projections.

← 2. The qualification mismatch index calculates the share of workers in each economy/occupation that are under- or overqualified to perform a certain job. This is done by computing the modal (i.e. most common) educational attainment level for each occupation in each country and point in time, and use this as a benchmark to measure whether individual workers’ qualifications match the “normal” education requirement of the occupation.

← 3. The data used here are taken from the shortage occupation lists published by the three Belgian public employment services: Le Forem for Wallonia (https://www.leforem.be/former/horizonsemploi/metier/index-demande.html); VDAB for Flanders (https://www.vdab.be/trends/knelpuntberoepen); and Actiris for The Brussels-Capital Region (http://www.actiris.be/Portals/36/Documents/NL/2019-knelpuntberoepen.pdf).

← 4. EU-LFS data does not go back to 1998 for Germany. Belgium’s share of manufacturing declined more than Germany from 2008 to 2018, which is the available reference point in Figure 3.7.

← 5. For industry wage premiums, the results obtain from fitting an OLS model by regressing real (2010 euros) log gross monthly earnings for full-time, low-educated workers on a set of worker and firm characteristics (age, sex, education, firm size) pooling over years 2014‑18. The regression results are used to estimate residuals at the individual level, which are then averaged by industry. The estimated average residual for each industry is rescaled by the mean log real wage from 2014‑18 giving the industry wage premium net of worker characteristics. The same procedure is employed for non-standard work but using a linear‑probability model. All results for non-standard work are industry-specific, percentage point deviations from the mean incidence of non-standard work among low-educated workers.