This chapter summarises they key insights emerging from the five case studies that are described in detail in the remainder of the report. It provides insights on how those five case study countries structure their landscape of vocational education and training (VET) providers. Moreover, the chapter provides pointers on how to foster transparency and consistency and how to encourage co-ordination between VET providers.

The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training

1. Key insights on vocational education and training providers in the case study countries

Abstract

Introduction

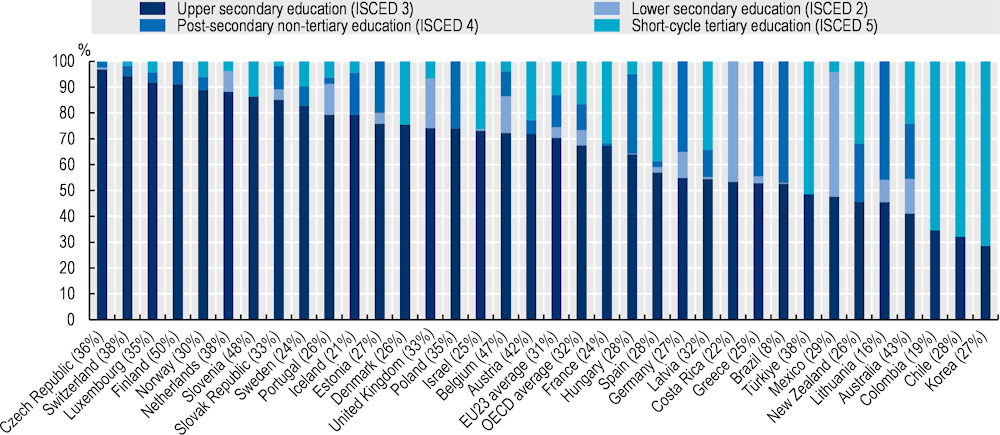

Vocational education and training (VET) comes in many shapes and forms. It is delivered at various levels of education (see Figure 1.1), covers different fields of study, and can be organised as entirely school‑based or a combination of school- and work-based learning (e.g. apprenticeship). VET generally has a more diverse student population than general education, including in terms of students’ age. As a result, the provider landscape in VET is diverse in many countries, with no single provider type welcoming students from all levels, fields, programme types and age groups.

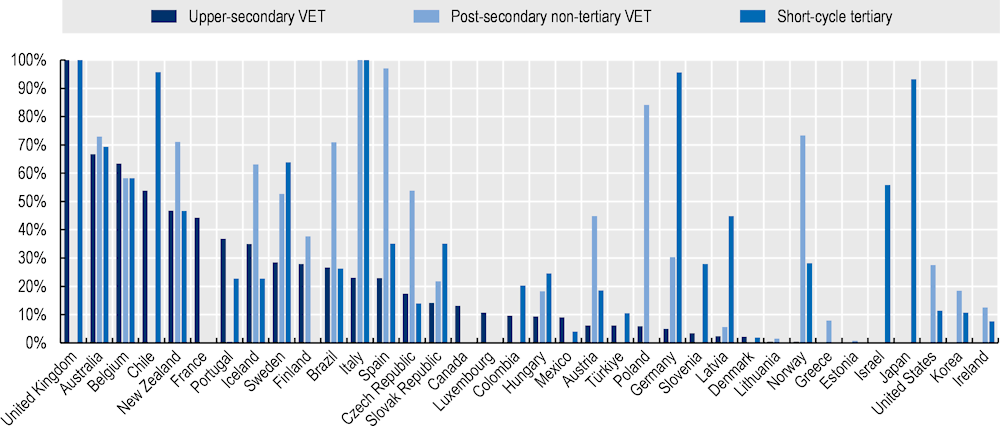

Comparative data on the provider landscape in VET are limited at the international level. The main indicators available concern student enrolment in public and private institutions, with the distinction made according to whether a public agency or a private entity has the ultimate control over the institution. Figure 1.2 shows that countries differ strongly in terms of the share of VET students who graduated from private institutions. Moreover, the prevalence of private providers also differs within countries by level of VET. There are also differences in terms of private institutions’ dependence on funding from government sources, with some countries having mostly independent private providers (receiving no or limited core funding from government sources), and others having mostly government dependent private providers (e.g. in Belgium all private VET providers are government dependent, while in Ireland, they are all independent private providers).1

Figure 1.1. Distribution of students enrolled in vocational education by level of education

Note: Figures in parentheses refer to the share of students enrolled in vocational education from lower secondary to short-cycle tertiary (International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED] levels 2 to 5) as a percentage of all students enrolled at these levels. For the United Kingdom, short-cycle tertiary programmes include a small number of bachelor's professional programmes.

Source: OECD (2020[1]), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

Figure 1.2. Graduates from private institutions

Note: Private institutions include independent private educational institutions and government dependent private educational institutions. Short‑cycle tertiary education (ISCED level 5) includes general and vocational programmes, but as described in OECD (2022[2]) most programmes at this level are vocational. Information for upper-secondary VET missing for Ireland, Japan, Korea and United States; for post‑secondary non-tertiary VET for Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Israel, Japan, Mexico, Republic of Türkiye, Slovenia and United Kingdom; for short-cycle tertiary for Canada, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Lithuania and Luxembourg.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), Education at a Glance Database, OECD.Stat website, https://stats.oecd.org.

This report looks at the provider landscape in Australia, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden to describe the different VET provider types (focusing on formal VET at levels 3-5 of the International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED), how they are different and how they overlap, as well as structures and initiatives to foster co-ordination between them. The remaining chapters of this report present each case study country (see Box 1.1 for an overview).

Box 1.1. About this report

This report looks at the VET provider landscape in Australia, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden to describe the different VET provider types. It focuses on formal VET at levels 3-5 of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). The purpose of the report is to provide a description of the landscape in the selected countries. It does not to provide recommendations on how countries should (re-)structure their provider landscape.

The remaining chapters in this report (Chapters 2 to 6) provide a description of the landscape of providers in the five case study countries. Each chapter includes a short description of the country’s VET system, and provides an overview of the various VET providers, with a particular focus on how the various providers differ in terms of target population and focus area, as well as looking at whether they are public or private providers. The chapters also describe co-ordination mechanisms and initiatives in place in the countries.

The structure of each case study chapter is as follows:

The country’s VET system: providing a short overview of how the VET system is structured, with a focus on programmes at ISCED levels 3 to 5.

The VET provider landscape: providing an overview of the different VET providers, highlighting differences in focus areas (e.g. field of study, types of delivery), target audience (e.g. adults vs. young students) and private versus public providers.

Co-ordination between provider types: providing a description of how the provision of different providers is aligned, and how co-ordination is encouraged and facilitated.

This first chapter summarise key differences and commonalities between the countries and provides pointers on how to make VET provider landscapes transparent, and how to achieve consistency and enable co-ordination.

The landscape of VET providers in the case study countries

The five case study countries all have a sizeable VET sector but differ substantially in how VET is designed and delivered. The provider landscape is distinct in each of these countries, but some key commonalities emerge:

All countries have both public and private VET providers, with the latter generally receiving public funds to deliver accredited programmes. Typically, public and private providers can provide the same programmes for the same target audience. However, private providers are more likely to target certain fields or sectors and attract more adult learners. Among the selected countries, this is the case in Australia and Sweden (and Germany and the Netherlands to a more limited extent).

In most countries, VET programmes at different levels of education are provided by different provider types. This is particularly the case for post-secondary or tertiary programmes, which are usually provided by different institutions than VET programmes at lower levels. Among the selected countries, this is the case in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Various countries have specialised VET provider types that focus on programmes in one or a limited set of education fields (e.g. agriculture, health). However, such specialised providers often co-exist with providers that deliver programmes in a broad range of fields, and in most cases those broader providers are not excluded from providing the fields for which specialised providers exist. Among the selected countries, this is the case for example in Germany and the Netherlands.

Some countries have dedicated provider types for adult VET. In some cases these are the only providers that can deliver VET to adult learners, while in other cases the dedicated adult VET providers share the responsibility with providers that cater to young students and adult learners. In Germany, adults can prepare for professional examinations only with independent providers and not with the main public providers. Likewise, Sweden has dedicated public and private providers for adults. In Denmark adult education centres provide dedicated VET programmes for adults, but adults can also choose to enrol in vocational colleges which also deliver initial VET programmes.

In countries where VET can be organised as a school-based track and apprenticeship track, these separate tracks are sometimes delivered in different institutions. This is the case, for example, in Germany, where vocational schools are the only provider type that delivers dual VET programmes at the upper-secondary level. VET programmes outside the dual VET system are delivered by other provider types.

The case studies show that there are many different ways for countries to organise their VET system. There is not one ideal system, and how the provider landscape is structured depends strongly on the role and design of VET. Moreover, differences between countries also reflect broader factors, with liberal market economies often having a larger private provider market and giving more freedom to providers on what types of programmes to deliver and their target audience.

Co-ordination between VET providers in the case study countries

What is clear from the case studies is that not one single system has a VET provider landscape without overlaps between the different providers in terms of programmes or target audience. The overlap is larger in some countries than in others, with some having limited differentiation between providers (often in an effort to create a competitive market), and others having a relatively segmented provider landscape that has overlaps only in a few fields or programme types. However, all systems require co‑ordination efforts and tools to make the system easy to navigate for learners, employers and other stakeholders. Overlapping provision is not necessarily an issue and may even foster innovation and quality when there is healthy competition between providers, but the system needs to remain transparent. In that respect, key messages are:

When overlap between provider types is large and students can follow the same programme with various provider types that are similar (as is the case mostly for private and public providers), information needs to be available on the quality of the providers. Moreover, when there are differences between these provider types in terms of fees, this needs to be clearly communicated. This will help students make informed choices.

When students can choose between a specialised provider (in terms of target audience and/or field) or a broader provider offering the same programmes, students need to be aware of the options available and their pros and cons (e.g. in terms of institution size, networks with industry, articulation options).

Standards need to underpin the training programmes, so that the targeted learning outcomes of programmes are the same across providers. Moreover, regulations need to exist for training providers to be able to deliver accredited VET programmes. Providers should be evaluated on a regular basis to ensure they continue to adhere to those regulations and that the programmes they deliver develop the skills defined in the training standards. Regulations and standards need to be transparent for the providers, and the outcomes of evaluations should be communicated widely.

Co‑ordination between the provider types should be encouraged. This can be done, for example, through formal co‑ordination bodies and knowledge sharing platforms. While there are often bodies representing the institutions within a provider type, there are much fewer efforts to bring together the different provider types in the selected countries.

References

[3] OECD (2022), OECD Education at a Glance Database, OECD.Stat website, https://stats.oecd.org.

[2] OECD (2022), Pathways to Professions: Understanding Higher Vocational and Professional Tertiary Education Systems, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a81152f4-en.

[1] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

Note

← 1. A government-dependent private school receives 50% or more of its core funding from government agencies or its teaching personnel are paid by a government agency. An independent private school receives less than 50% of its core funding from government agencies and its teaching personnel are not paid by a government agency. The terms “government-dependent” and “independent” refer only to the degree of a private institution’s dependence on funding from government sources, and not to the degree of government direction or regulation.