This chapter looks at the landscape of vocational education and training (VET) providers in Sweden. It describes the Swedish VET system and zooms in on the different types of institutions that provide VET programmes. The chapter looks at how providers differ in terms of target audience, as well as the role of private and public providers. Lastly, the chapter also discusses how different types of providers are co‑ordinated and how they collaborate.

The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training

6. Sweden’s landscape of vocational education and training providers

Abstract

The Swedish vocational education and training system

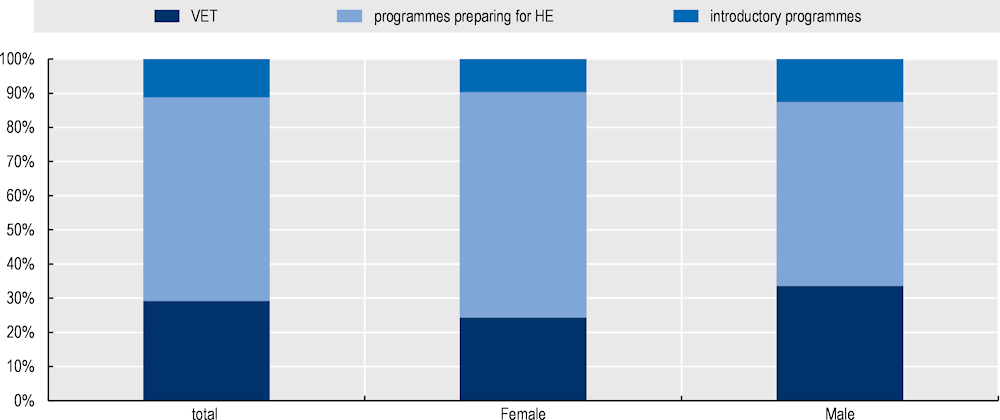

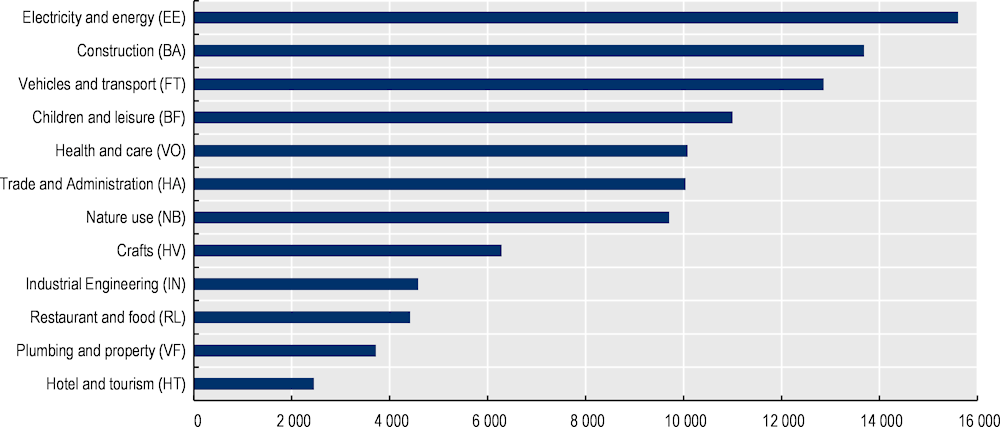

Students who successfully complete compulsory education (typically aged 16) can apply for one of 18 national upper-secondary programmes, 12 of which are vocational. Students who do not qualify for national upper-secondary programmes attend introductory programmes preparing them for the transition into one of the national upper-secondary programmes or into the labour market (Skolverket, 2021[1]). About 30% of students are in VET programmes and 11% in introductory programmes, with these shares being higher among male than female learners (see Figure 6.1). Among the 12 VET programmes, electricity and energy and construction attract the largest number of students (see Figure 6.2). All national upper‑secondary VET programmes last three years. Students in vocational programmes can attend a mainly school-based track or an apprenticeship track. In the latter at least half of the learning is work‑based. Approximately 13 % of students in vocational upper-secondary programmes are in the apprenticeship track (Skolverket, 2021[2]). School-based VET and apprenticeships have the same learning objectives and lead to the same qualifications.

Figure 6.1. Share of upper-secondary students by type of programme in Sweden, 2020/21

Note: HE is higher education.

Source: Skolverket (2021[3]), Statistik över gymnasieskolans elever 2020/21, https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/fler-statistiknyheter/statistik/2021-03-11-statistik-over-gymnasieskolans-elever-2020-21.

The scope of the courses in upper-secondary education is defined by upper-secondary credits, indicating the relative weight of the course in the full programme. All upper-secondary school programmes include the same eight core required subjects, but the scope and therefore also the amount of credits associated with the core/foundation subjects differ across vocational and general programmes (i.e. programmes preparing for higher education). In addition to the core required subjects, students study programme‑specific subjects. General and vocational programmes are provided within the same institutions and education is delivered on a full-time basis. Students who have completed upper-secondary school with basic eligibility for higher education can apply to universities (universitet), university colleges (högskola) and/or higher vocational education providers (yrkeshögskola) (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[4]).

At the post-secondary level, higher vocational education (HVE) was established in 2009 in its current form, to fill a gap in the education market by providing postsecondary non-university programmes closely connected to labour market needs. Most HVE programmes require between six months and two years of full-time study with 70% of programmes lasting two years. A programme of at least one year (equivalent to 200 HVE credits) can lead to a diploma qualification and a programme of at least two years (equivalent to 400 HVE credits) can lead to an advanced diploma. They are classified at ISCED level 4 and 5, respectively (Cedefop, 2016[5]). In 2020 there were 3 016 ongoing HVE training programmes in 14 fields, including construction, finance, administration, sales, IT, tourism, healthcare, agriculture, media, design, engineering and manufacturing (Cedefop, 2019[6]). To establish a new HVE programme, education providers must secure employers’ involvement. The providers, in collaboration with employers, propose programmes to the National Agency for HVE which may then be funded for up to five training periods. After that, a new application must be filed to the Agency to ensure that the programme still meets the needs of the labour market.

Figure 6.2. Number of upper-secondary VET students in Sweden, by programme (2020/21)

Source: Sveriges Officiella Statistik (2021[7]), Gymnasieskolan – Elever – Riksnivå: Elever på program redovisade efter typ av huvudman och kön, läsåret 2020/21 (Table 5 A), https://siris.skolverket.se/siris/sitevision_doc.getFile?p_id=550197.

The provider landscape

Upper-secondary schools in Sweden are mainly divided into municipal public schools (kommunala skolor) and independent ones (fristående skolor). HVE providers can be private education companies, municipalities, counties/regions, universities or other tertiary education providers or other government agencies. In addition to these main providers of initial upper-secondary and HVE, adult municipal education and folk high schools provide upper-secondary courses to adults who have not completed compulsory or upper-secondary education, but also to other target groups. These institutions also provide programmes at other levels of education as well as courses that are outside the formal education system.

Table 6.1. Overview of main VET providers in Sweden

|

Education level |

Private or public |

Key features |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Municipal schools |

ISCED 3 |

Public |

Public upper-secondary schools run by municipalities |

|

Independent schools |

ISCED 3 |

Private |

Upper-secondary schools run by third parties such as companies, foundations, and staff and parent co‑operatives |

|

Higher vocational education (HVE) providers |

ISCED 4-5 |

Public and private |

HVE providers can be private education companies, municipalities, counties/regions, universities or other tertiary education providers or other government agencies |

|

Adult education providers |

Various levels |

Public and private |

Organised by municipalities and often outsourced to private providers, delivering programmes for adults with low levels of qualifications |

|

Folk high schools |

Various levels |

Public and private |

Folk high schools provide formal and non-formal education for adults, delivered by various civic or social movement organisations and associations, as well as county councils and regions |

Note: More details about the various providers are provided in the following sections. ISCED 3: upper secondary education; ISCED 4: post‑secondary non-tertiary education; ISCED 5: short-cycle tertiary education.

Public vs. private providers

A series of reforms in the 1990s reinforced student choice and allowed private entities to establish private schools, also called independent schools. The aim of these reforms was to increase the educational offer and give more choice to students and parents. Hence, today upper secondary VET programmes are provided by municipal schools, run by the municipalities, and independent schools, run by third parties such as companies, foundations, and staff and parent co-operatives. Permission to start an independent school is issued by the School Inspectorate and is given on the condition that the school follows the nationally provided syllabus and teaches the same democratic values as schools run by the municipalities (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[4]). Six months after the start of school, the Inspectorate conducts a first-time inspection to ensure that the activities are conducted in the manner specified in the application. While empowerment of schools allowed them to address more effectively individual student needs and local labour market circumstances, competition created some risks. Competition among education providers for students inevitably creates an environment in which it is more challenging to encourage collaborative approaches (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[4]).

In 2020, 456 out of 1 307 upper-secondary schools were independent, which represents 35% of the sector. According to 2020 data, in 250 municipalities, out of a total of 290, there were upper-secondary schools run by municipalities, whereas independent upper-secondary schools could be found in 97 municipalities (Swedish Association of Independent Schools, 2022[8]). Overall, 28% (or 101 000) of the upper-secondary student population attend independent schools. Student performance in public and independent upper secondary schools is comparable. In the 2018/19 academic year, the average grade point for students in independent schools was 14.9, compared to 14.8 in municipal and county council-run schools. Independent upper-secondary schools tend to be smaller than municipal schools. An independent upper‑secondary school caters to 231 students on average, as compared to 294 students enrolled in municipally run institutions. There are 20 entities that have five or more school units in compulsory and upper-secondary education, ten of which are owned by private individuals, three are foundation-owned, two are staff-owned and three are listed on the stock exchange (Swedish Association of Independent Schools, 2022[8]).

Programmes run by public and independent upper-secondary schools lead to the same qualifications. Independent schools may offer any of the 18 national upper-secondary programmes, including VET, and introductory programmes. However, while municipalities have to serve all learners from the area, independent schools can target specific groups. Differences can indeed be observed. For example, municipalities enrol more students in introductory programmes designed for students who do not qualify for upper secondary education than independent schools. In terms of socio-economic background, 54% of students attending independent institutions have parents with post-secondary education, as compared to 52% in municipal schools (Swedish Association of Independent Schools, 2022[8]).

Upper-secondary education is free of charge to students. Most of the funding for upper secondary schools comes from municipal taxes and additional funds from the state budget. Independent upper-secondary schools are funded through a “voucher system” which allocates funds to schools depending on the number of students enrolled in the different programmes. The amount of funding per student and criteria according to which the funding is allocated are roughly the same for municipal and independent schools – the municipality pays the independent school the same amount per student as the municipal school would get. A key difference, however, is that while public school funds remain within the municipality, independent schools are able to keep and make use of the profits they make (Swedish Association of Independent Schools, 2022[8]). This means that an owner of an independent school may pay dividends to shareholders or invest the surplus in areas not related to education. Conversely, if a public school is left with a surplus by the end of the budgetary year, the surplus is reinvested in education.

Similarly, HVE providers can be public and private. In 2020, out of 214 institutions providing HVE, 121 were private while the rest belonged to local and regional authorities and the state (Swedish National Agency for Higher Education, 2020[9]). Over time, the proportion of private providers and training places at privately run institutions increased. In 2020, private providers offered 73% of training places as compared to 49% in 2007 (Swedish National Agency for Higher Vocational Education, 2021[10]). The various providers of HVE programmes must apply to the Agency for Higher Vocational Education for approval of the programmes they wish to deliver. HVE programmes are publicly funded, with no tuition fees. The overall budget for HVE is determined by the government and the Parliament and the Agency for HVE funds individual providers in the form of grants covering up to five training periods based on an evaluation of the programme and the provider.

Likewise, adult education is provided by public providers and private providers. Municipalities organise municipal adult education (komvux, see below), but they outsource some adult education courses to other, mainly private training providers, with education companies representing the overwhelming majority. In 2019, 50% of the participants in municipal adult education received training in a school operated by a provider other than municipality (Andersson and Muhrman, 2021[11]). The proportion of students in training provided by organisations other than the municipality has doubled over the past decade. A survey carried out among municipalities shows that municipalities hire external providers to offer a wider range of courses and to keep prices low through competition between education providers. However, this only works in larger municipalities where several providers compete to win the procurements. Many smaller municipalities reported difficulties to attract external providers (Andersson and Muhrman, 2021[11]). Municipalities pay for adult education, including courses delivered by other providers. They also ensure the quality of municipal adult education across all institutions. Private providers are typically selected through a public procurement process culminating in a selection of providers that can deliver education according to the required criteria at the lowest price. Some municipalities use an authorisation system, as in youth education, whereby municipalities define the price per course/student and the criteria the provider should fulfil. A survey of municipalities shows that there are issues with quality in some private providers and some municipalities envisage to expand its internal provision (Andersson and Muhrman, 2021[11]). Adult education is also provided by folk high schools (see below). There are a total of 155 Folk High Schools in Sweden, 111 of which are run by various civic or social movement organisations and associations, whilst the remaining 44 are run by county councils or regions (Eurydice, 2019[12]).

Target audience

Upper-secondary schools –both the municipal schools and the independent schools- mostly target young students coming directly from compulsory education. The learners in HVE are more diverse in age, with about 45% of the HVE students in 2021 being younger than 30, 42% between 30 and 45, and 13% aged 45 and older (Sveriges Officiella Statistik, 2022[13]).

Adults who want to study at the upper-secondary level can do so in municipal adult education and in Folk High Schools. Both types of institutions provide formal programmes at different education levels and Folk High Schools also offer a range of non-formal programmes. Their formal programmes at upper-secondary level lead to the same qualifications as the ones provided in upper secondary schools for youth.

Municipal adult education (komvux) is targeted at adults aged 20 and over who have not completed primary or upper-secondary education. Municipalities are legally obliged to offer this type of education. If a municipality does not provide a relevant course and the person attends adult education in another location, the home municipality pays its cost to the municipality or county council offering the education (Eurydice, 2020[14]). Students in municipal adult education can work towards a diploma that is equivalent to upper‑secondary school diploma, supplement earlier education to gain eligibility for higher education, and get vocational training. Learning goals of municipal adult education are the same as in upper-secondary education for youth but there are no nationally determined programmes. Instead, adults study one or more courses based on their specific needs and preconditions. Municipal adult education is free of charge for participants (Eurydice, 2020[14]; Skolverket, 2021[1]). In 2019, 4,3% of 20-64 year-olds or 387 000 students were enrolled in municipal adult education (Andersson and Muhrman, 2021[11]). Over 175 000 students, studied at upper-secondary level (Eurydice, 2020[14]).

Adults can also attend Folk high schools (Folkhögskola) to enrol in programmes at the level of compulsory or upper-secondary school education. These so-called general courses must represent at least 15% of every folk high school’s programme for them to receive public financing or government grants. The minimum age for admission to the general courses is 18 years. In addition, folk high schools can provide vocational courses at post-secondary level (e.g. course in sign language translation) and special courses that do not confer eligibility for higher education (such as in music, textiles, globalisation and many other subjects) (Eurydice, 2019[12]). Folk high schools have freedom to develop their own courses, and they do not follow a centrally established, standard curriculum but develop their own teaching plans within the limits set by a special ordinance. Education in folk high schools is free of charge and the schools receive financial support from the state. In 2020, 30 646 adults participated in general courses, 45 837 in special courses of 15 days or longer, and 28 944 took part in short courses of less than 15 days (Statistics Sweden, 2022[15]).

Co‑ordinating between provider types

All upper-secondary schools, municipal and independent, are run according to the prescriptions of the Education Act and its accompanying Upper Secondary School Ordinance, and goals for upper-secondary VET are set nationally. Within a nationally defined curriculum, schools choose which courses to offer to meet local and regional needs. Measures of quality are also defined nationally and all upper-secondary schools are evaluated by the Swedish School Inspectorate. Whereas the rules according to which upper‑secondary VET programmes can be run are the same for municipal and independent schools, municipalities are obliged to ensure that all young people have access to upper-secondary education placing them in a slightly different situation than private providers (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[4]). This means that independent schools can target ‘easier to teach’ students. They may also privilege VET programmes that are cheaper to provide and do not require heavy upfront investment (for example in terms of equipment). There is not much co‑operation between independent and municipal institutions as they compete for students. For example, it has been observed that municipal schools increased marketing activities in response to the introduction of the market in youth education in the 1990’s (Lundahl et al., 2013[16]).

At the HVE level, the Swedish National Agency for HVE plays a central role in ensuring the relevant regulations are observed and co‑ordinating the different training providers. The Agency ensures that HVE programmes meet the labour market's needs for skills, by analysing skill needs and on this basis deciding which programme to offer. The Agency also allocates government grants, conducts reviews, produces statistics and promotes quality improvement in HVE (Myndigheten för yrkeshögskolan, n.d.[17]). The HVE providers must apply to the Agency for Higher Vocational Education for approval of new programmes. To establish a new HVE programme, education providers must secure employers’ involvement, and HVE is thus driven by employer demand for labour and skills rather than student choice. The National Agency for HVE allocates funding for training programmes on the basis of labour market needs and also takes into account the suitable geographical location for each training programme. Providers cannot expand unless they receive support from employers and funding from the National Agency of HVE. This mechanism prevents expansion of programmes that are popular with students but lead to poor labour market outcomes. It ensures that the offer of each provider reflects the demand from the labour market for the associated skills, and the incentives to compete for students are weak.

References

[11] Andersson, P. and K. Muhrman (2021), “Marketisation of adult education in Sweden”, Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, p. 147797142110554, https://doi.org/10.1177/14779714211055491.

[6] Cedefop (2019), Sweden: higher vocational education continues to expand, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/sweden-higher-vocational-education-continues-expand-0.

[5] Cedefop (2016), Refernet. Sweden: VET in Europe: country report 2016, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/country-reports/sweden-vet-europe-country-report-2016.

[14] Eurydice (2020), Sweden: Main types of provision, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/main-types-provision-77_en.

[12] Eurydice (2019), Sweden: Main providers, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/main-providers-77_en.

[4] Kuczera, M. and S. Jeon (2019), Vocational Education and Training in Sweden, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9fac5-en.

[16] Lundahl, L. et al. (2013), “Educational marketization the Swedish way”, Education Inquiry, Vol. 4/3, p. 22620, https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i3.22620.

[17] Myndigheten för yrkeshögskolan (n.d.), Swedish National Agency for Higher Vocational Education, https://www.myh.se/in-english.

[2] Skolverket (2021), Apprenticeships in upper secondary school, https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/regeringsuppdrag/2021/larlingsutbildningen-i-gymnasieskolan (accessed on 14 February 2022).

[1] Skolverket (2021), Statistik över gymnasieskolans elever 2020/21, https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/arkiverade-statistiknyheter/statistik/2021-03-11-statistik-over-gymnasieskolans-elever-2020-21 (accessed on 6 January 2022).

[3] Skolverket (2021), Statistik över gymnasieskolans elever 2020/21, https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/fler-statistiknyheter/statistik/2021-03-11-statistik-over-gymnasieskolans-elever-2020-21.

[15] Statistics Sweden (2022), Folk high school statistics. Participants in folk high school courses by sex, type of course, national background, region and age. Year 2017 - 2020, https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__UF__UF0601/.

[13] Sveriges Officiella Statistik (2022), Studerande och examinerade i yrkeshögskolan. Antal studerande efter kön, utbildningens inriktning, ålder och år, https://www.scb.se/UF0701.

[7] Sveriges Officiella Statistik (2021), Gymnasieskolan – Elever – Riksnivå: Elever på program redovisade efter typ av huvudman och kön, läsåret 2020/21 (Tabell 5 A), https://siris.skolverket.se/siris/sitevision_doc.getFile?p_id=550197.

[8] Swedish Association of Independent Schools (2022), Facts about independent schools, 2022, https://www-friskola-se.translate.goog/fakta-om-friskolor/?_x_tr_sl=sv&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en.

[9] Swedish National Agency for Higher Education (2020), Statistik. Faktablad med kortfattad statistik om yrkeshogskoland, 2020, https://www.myh.se/in-english (accessed on 6 January 2022).

[10] Swedish National Agency for Higher Vocational Education (2021), Statistisk Arsrapport, http://assets.myh.se.