This chapter looks at the landscape of vocational education and training (VET) providers in Australia. It describes the Australian VET system and zooms in on the different types of institutions that provide VET programmes. The chapter looks at how providers differ in terms of focus areas of the provided training and target audience, as well as the role of private and public providers. Lastly, the chapter also discusses how different types of providers are co-ordinated and how they collaborate.

The Landscape of Providers of Vocational Education and Training

2. Australia’s landscape of vocational education and training providers

Abstract

The Australian vocational education and training system

Vocational education and training (VET) qualifications in Australia are defined at the national level and are mostly delivered as a post-school option (i.e. not as part of the standard secondary education system). Vocational qualifications include: Certificate I and II (ISCED level 2), Certificate III (ISCED level 3), Certificate IV (ISCED level 4), Diploma and Advanced Diploma (ISCED level 5), and Graduate Certificate and Graduate Diploma (ISCED level 6). In 2021, 2.1 million students were enrolled in nationally recognised programmes (NCVER, 2022[1]).1

While vocational qualifications are mostly delivered outside of secondary education, some senior secondary schools allow their students to pursue parts of these qualifications (“VET in schools”). In 2021, there were 230 700 Australian students undertaking VET as part of their senior secondary certificate (excluding school-based apprentices) (NCVER, 2022[1]). VET is also delivered to secondary students through School-Based Apprenticeships and Traineeships and Australian School-based Apprenticeships, which provides a combination of school-based and workplace learning. In 2021, 25 500 students were in school-based apprenticeships (NCVER, 2022[1]).

Moreover, secondary schools can also offer some VET courses that are not part of vocational qualifications, with course content that can be very different between jurisdictions, and even in some cases within jurisdictions. Over 95% of secondary schools offer VET subjects and around 40% of all upper secondary students undertake at least one VET subject. (OECD, 2020[2]).

The provider landscape

Vocational qualifications are delivered by registered training organisations (RTOs). RTOs can be classified into six types: private training providers; state- and territory-owned Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes; schools; community education providers,2 universities; and enterprise providers that primarily provide training to their own employees. To become an RTO, an organisation must meet a range of mandatory requirements to ensure its training and assessment services are delivered to the standards expected by students and employers.

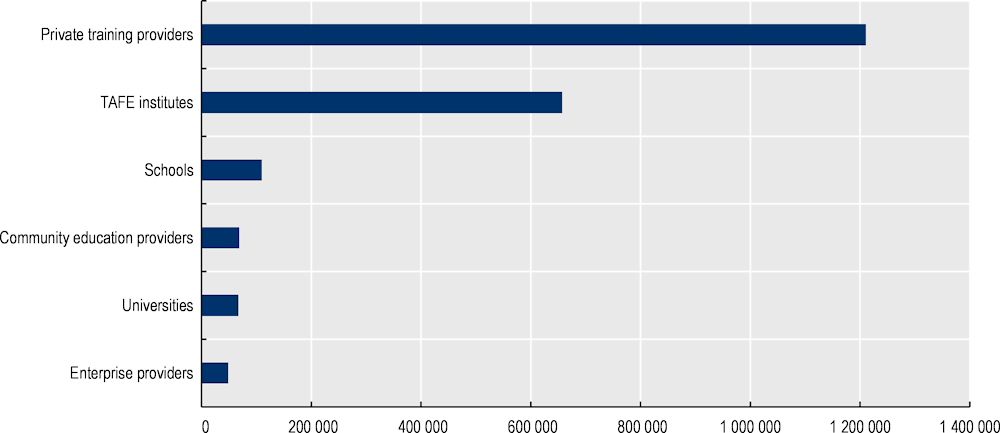

Private training providers and TAFE institutes are the largest VET providers, respectively accounting for 59% and 32% of students in nationally recognised programmes (see Figure 2.1). There are many more private training providers than there are TAFEs: on 31 December 2021, there were 3 115 private training providers registered as an RTO, compared to only 24 TAFEs. This reflects that the majority of TAFEs are large multi-campus institutions, whereas private providers are in many cases small. Data from 2014 showed that the median size of a TAFE equalled around 17 000 students (20 000 average), compared to only around 200 students in private training providers (800 average) (Korbel and Misko, 2016[3]). Nonetheless, private providers exist in many sizes, with some of them being as large as TAFEs.

While universities are one of the six provider types, most Australian universities’ vocational education programmes are small in size, confined to one campus, are in one or two disciplines, and many are offered through separate organisational units. Some of those offerings are historic leftovers, and often the result of the amalgamations with previously single sector institutions. However, there are a few exceptions, where vocational education is a substantial part of the universities’ operations (Moodie, 2009[4]). These are generally referred to as dual sector universities. They are characterised by strong industry partnerships and a strong focus on applied learning (Maddocks et al., 2019[5]).

Figure 2.1. Number of students by type of RTO (2020)

Note: Student numbers by provider may not sum to the total, as students may enrol in more than one provider type. Only includes students in nationally recognised programmes.

Source: NCVER (2021[6]), Total VET students and courses 2020, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/total-vet-students-and-courses-2020.

Table 2.1. Overview of main VET providers in Australia

|

Provider type |

Education level |

Private or public |

Key features |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Private training providers |

Various levels |

Private |

Ranging from small providers focusing on a specific field or specialisation to very large providers providing programmes in multiple fields |

|

Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes |

Various levels |

Public |

Large state- and territory-owned institutes |

|

Schools |

Predominantly ISCED levels 2 and 3 |

Both |

Schools predominantly provide general education at ISCED levels 3 and below |

|

Community education providers |

Various levels |

Private |

Various types of organisations (e.g. Neighbourhood Houses and Centres) |

|

Universities |

Various levels |

Both |

Universities’ vocational education programmes are usually small in size, confined to one campus, focused on one or two disciplines, and mostly offered through separate organisational units |

|

Enterprise providers |

Various levels |

Private |

Primarily provide training to their own employees |

Note: More details about the various providers are provided in the following sections. ISCED 2: lower secondary education; ISCED 3: upper secondary education.

Focus areas

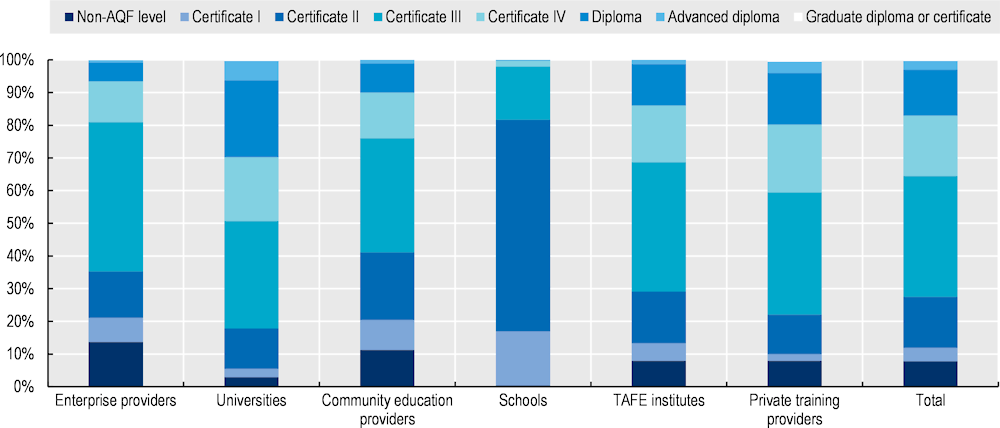

All providers deliver programmes at various levels of education, although some providers focus more on higher-level qualifications and others on lower-level qualifications, see Figure 2.2. For example, around 50% of VET students in universities are in programmes at ISCED level 4 or above, while –unsurprisingly- 80% of VET students in schools are in certificate I or II programmes (NCVER, 2021[6]). Enterprise providers and community education providers have a similar pattern of student enrolment by level, with the latter having slightly higher enrolment in lower-level programmes (Certificate I or II). TAFE institutes and private training providers are similar in enrolling students at various education levels, with TAFE institutes having a slightly higher share of students in lower-level programmes and lower share in higher-level programmes (ISCED level 4 or above).

Figure 2.2. Level of education of students, by RTO type (2020)

Notes: Only includes students in nationally recognised programmes.

Source: NCVER (2021[6]), Total VET students and courses 2020, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/total-vet-students-and-courses-2020.

TAFE institutes are large institutions, providing a wide range of VET qualifications in various fields. By contrast, private training providers are often small, focusing in some cases on a very specific field or specialisation. However, this is not always the case, and many private training providers –especially the larger ones- provide training in multiple fields. The same holds for the other types of providers, which in some cases are highly specialised and in other cases provide a broader set of training programmes.

Target audience

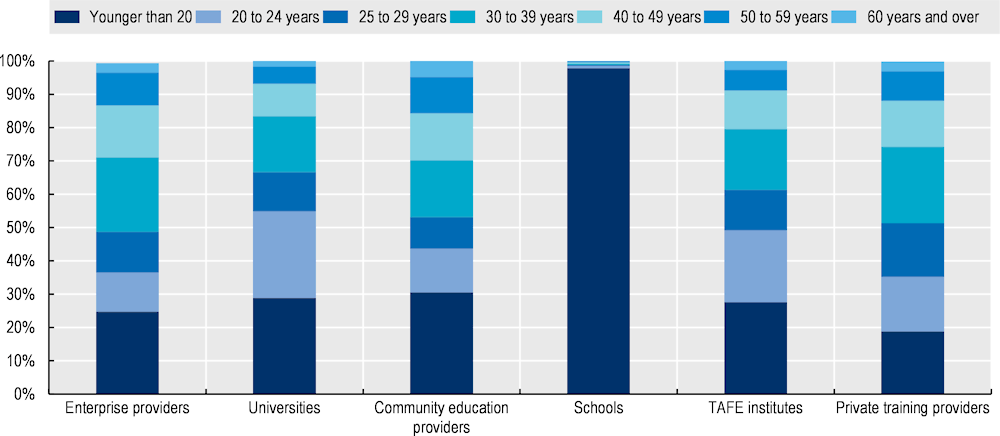

As highlighted above, VET in Australia is mostly organised as a post-school option, and therefore attracts many adult learners. While the age composition of students differs slightly between provider types, providers clearly do not focus on one single age group, see Figure 2.3. The exception is schools, in which almost all students are younger than 20. TAFE institutes and universities have a larger share of young students (below 25) than the other provider types, reflecting that these institutions are often seen as providing a direct pathway after secondary education. Private training providers and enterprise providers have the lowest share of young students, which is possibly linked to the narrow focus of many of these institutions on a particular field or sector allowing for upskilling opportunities for workers.

Figure 2.3. Age composition of students, by RTO type (2020)

Notes: Only includes students in nationally recognised programmes.

Source: NCVER (2021[6]), Total VET students and courses 2020, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/total-vet-students-and-courses-2020.

Private versus public providers

TAFE institutes are public providers, which is the key element of distinction compared to the large group of private providers. The VET market in Australia was opened up in the early 1990s, with the goal to increase efficiency and effectiveness of the training system (Anderson, 1997[7]).

A significant share of private RTOs also receive public funding. Nationally, government payments to non‑TAFE providers amounted to AUD 1.1 billion in 2019, accounting for 21% of all appropriations and programme funding from government for VET (Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2021[8]). Students at private institutions can also make use of public financial support, such as incentive payment and VET Student Loans (VSL). Students studying eligible courses at the diploma and above level can access VSL - income contingent loans financed by the Australian government to cover some or all of the cost of their study. VET providers must apply to become an approved VSL provider and the criteria are rigorous. In 2019 there were 194 approved VSL providers, 23 being public providers with 60.7% of students, 158 private providers with 25.2% of students and 13 other types of providers (e.g. not for profit) with 14.1% of students. In 2019, AUD 134.4 million in loans were made to students studying at public providers, AUD 105.3 million to students at private providers and AUD 36.2 million to students at other public providers.

The opening up of the VET market has posed certain challenges in Australia. The practice of allocating VET funding via competitive tendering between public and private providers has been reported to have meant that certain providers have been squeezed into lowering their aspirations (Hager, 2019[9]). Moreover, unethical and fraudulent activities in the VET sector have been discovered. (Hager, 2019[9]).

Outcomes by provider type

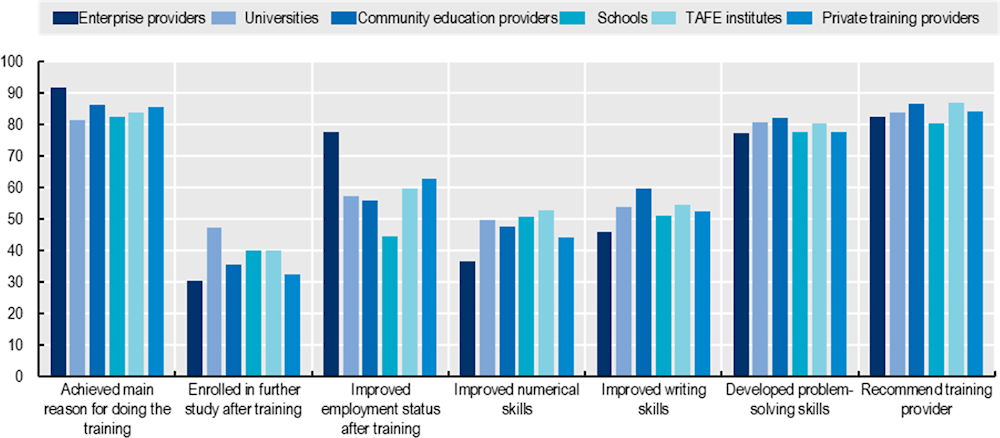

The National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) conducts on an annual basis the National Student Outcome Survey, collecting information on outcomes and satisfaction of students who completed nationally recognised VET delivered by RTOs in Australia. Figure 2.4 shows the results of a selected set of indicators by provider type. Differences between providers are generally small, and often reflect the different target audience and focus area of providers. For examples, those who took their training in universities, schools and TAFEs are more likely to continue in further study, as these institutions are more often seen as part of initial education, attract younger students and in some cases provide clear pathways into further learning. Those who completed their training with enterprise providers are more likely to report that they improved their employment status, which is linked to the fact that often these individuals followed training with their own employer in an effort to upskill or reskill in line with their own or the enterprise’s needs. TAFEs, universities and community education providers are more likely than other providers to develop the numerical, writing and problem-solving skills of their students. These average can of course mask differences between providers within the same type.

Figure 2.4. Outcomes and satisfaction of students who completed nationally recognised VET delivered by RTOs during 2020

Note: Only includes qualification completers.

Source: NCVER (2021[10]), VET student outcomes 2021, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/collections/student-outcomes/vet-student-outcomes.

Co‑ordinating between provider types

As highlighted above, the Australian provider landscape is complex, with no clear distinction between the different types of RTOs. The only exception is schools, which focus almost entirely on Certificate levels I, II and III for students younger than 20 – although a small number of older students and students in higher‑level programmes are also enrolled in schools.

To ensure the quality of the providers and some degree of consistency, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) was created. ASQA accredits courses and regulates RTOs to ensure nationally approved quality standards are met. ASQA has jurisdiction over all RTOs, except for those that are state accredited and operate solely in Victoria or Western Australia (and do not offer courses to interstate and overseas students). ASQA is a relatively new regulator, having been established on 1 July 2011 under the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act. ASQA monitors RTO compliance against the requirements of the Act and its VET Quality Framework. Its primary functions are to oversee the entry of RTOs into the market, accredit courses, carry out compliance audits and penalise non-compliance, including cancelling the registration of poor providers. All RTOs registered with ASQA are required to provide an annual summary report of their performance against learner engagement and employer satisfaction quality indicators.

RTOs are required to comply with the Standards for Registered Training Organisations 2015. These Standards form part of the VET Quality Framework, a system which ensures the integrity of nationally recognised qualifications. The purpose of these Standards is to: i) set out the requirements that an organisation must meet in order to be an RTO; ii) ensure that training products delivered by RTOs meet the requirements of training packages or VET accredited courses and have integrity for employment and further study; and iii) ensure RTOs operate ethically with due consideration of learners’ and enterprises’ needs. There are six standards under three broad headings: training and assessment; obligations to learners and clients; and RTO governance and administration. The Standards describe outcomes RTOs must achieve, but do not prescribe methods by which RTOs should achieve these outcomes. This allows RTOs to be flexible and innovative in their VET delivery—an acknowledgement that each RTO is different and needs to operate in a way that suits their clients and students (ASQA, 2021[11]).

The need for more and better co‑ordination between the different types of providers in the Australian VET system is widely acknowledged, and various initiatives have been set up. In Victoria, for example, the Victorian Skills Authority was established in mid-2021 as the key link between the state’s industries, training providers, employers and communities. One of its roles is to strengthen connections between TAFE, training, higher education and adult community education.

To help prospective students navigate the complex provider landscape, the MySkills website allows users to search for training providers, giving an indication about the availability of subsidies, VET student loans, and online delivery options. The provider list also flags where an RTO has a regulatory decision attached (e.g. conditions applied to their registration by ASQA). For each provider, users can see the courses that are delivered, as well as information supplied voluntarily by RTO about fees, campuses, delivery options, and student services.

The ongoing Skills Reform aims to strengthen the VET System, so as to provide high-quality, responsive and accessible education and training to boost productivity and support Australians to obtain the skills they need to participate and prosper in the modern economy. Reforms are also improving industry and employer engagement in Australia’s VET sector. In addition to these immediate reforms, the Australian, state and territory governments have committed to work collaboratively on long-term improvements to the VET sector through a new National Skills Agreement.

References

[7] Anderson, D. (1997), Competition and market reform in the Australian VET sector, NCVER, https://www.ncver.edu.au/__data/assets/file/0017/16514/td_tnc_51_08.pdf.

[11] ASQA (2021), About the Standards for RTOs 2015, https://www.asqa.gov.au/standards/about.

[8] Australian Government Productivity Commission (2021), Report on Government Services 2021: PART B, SECTION 5 Vocational Education and Training, https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2021/child-care-education-and-training/vocational-education-and-training.

[9] Guile, D. and L. Unwin (eds.) (2019), VET, HRD, and Workplace Learning: Where to From Here?, Wiley-Blackwell, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119098713.

[3] Korbel, P. and J. Misko (2016), VET provider market structures: history, growth and change, NCVER, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/vet-provider-market-structures-history-growth-and-change.

[5] Maddocks, S. et al. (2019), “Reforming post-secondary education in Australia: perspectives from Australia’s dual sector universities”, http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/502120.

[4] Moodie, G. (2009), Australia: The emergence of dual sector universities, Routledge, https://researchrepository.rmit.edu.au/discovery/delivery/61RMIT_INST:ResearchRepository/12246602710001341?l#13248411270001341.

[1] NCVER (2022), Latest VET statistics, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/visualisation-gallery/latest-vet-statistics.

[10] NCVER (2021), VET student outcomes 2021, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/collections/student-outcomes/vet-student-outcomes.

[6] NCVER (2021), Total VET students and courses 2020, https://www.ncver.edu.au/research-and-statistics/publications/all-publications/total-vet-students-and-courses-2020.

[2] OECD (2020), Improving Work-based Learning in Schools: Note on Australia, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/skills/centre-for-skills/Improving_Work-based_Learning_In_Schools_Note_On_Australia.pdf.

Notes

← 1. These include training package qualifications, accredited qualifications, training package skill sets, accredited courses.

← 2. Adult and Community Education providers are a disparate group that go by various names including: Neighbourhood House and Centre, community men’s shed, University of the Third Age, Community College and various other names. Provision of formal VET is a focus for some Adult and Community Education providers. These include some Neighbourhood Houses and Centres, all Community Colleges (in New South Wales and Victoria) and Adult and Community Education providers that go by other names.