Infant mortality reflects the effect of social, economic, and environmental factors on infants and mothers, as well as the effectiveness of national health systems.

Pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria continue to be amongst the leading causes of death in infants. Cost-effective and simple interventions as those comprised in the EENC are key to reduce infant mortality (see section “Neonatal mortality”). Factors such as the health of the mother, quality of antenatal and childbirth care, preterm birth and birth weight, immediate newborn care and infant feeding practices are important determinants of infant mortality.

Infant mortality can be reduced through cost-effective and appropriate interventions -akin to the EENC interventions for newborns. These interventions include proper infant nutrition; provision of supportive health services such as home visits and health check-ups; immunisation and controlling the influence of environmental factors such as air pollution; and access to safely managed water and sanitation services. Management and treatment of neonatal infections, pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria is also critical (UNICEF, 2013[1]).

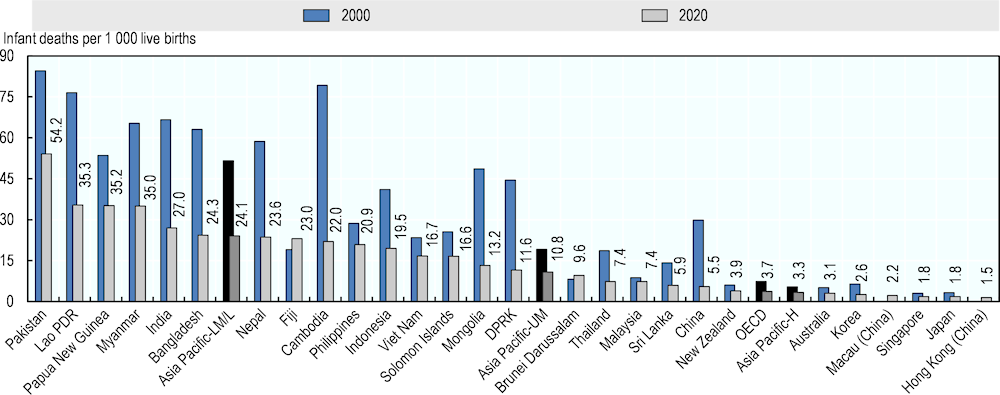

In 2020, amongst lower-middle- and low-income Asia-Pacific countries and territories, the infant mortality rate was 24.1 deaths per 1 000 live births, less than half the rate observed in 2000 (Figure 3.7). Upper-middle-income Asia-Pacific countries and territories reported a rate of 10.8 deaths per 1 000 live births, down from 19.1 in 2000. Geographically, infant mortality was lower in eastern Asian countries and territories, and higher in South and Southeast Asia. Hong Kong (China), Japan, Singapore, Macau (China) and Korea had less than three deaths per 1 000 live births in 2020, whereas in Pakistan more than five children per 100 live births die before reaching their first birthday.

Infant mortality rates have fallen dramatically in the Asia-Pacific since 2000, with many countries and territories experiencing significant declines (Figure 3.7). In China, DPRK, Mongolia and Cambodia, rates have declined in 2020 to one‑third or less of the value reported in 2000, whereas rates in Fiji and Brunei Darussalam have increased in recent years.

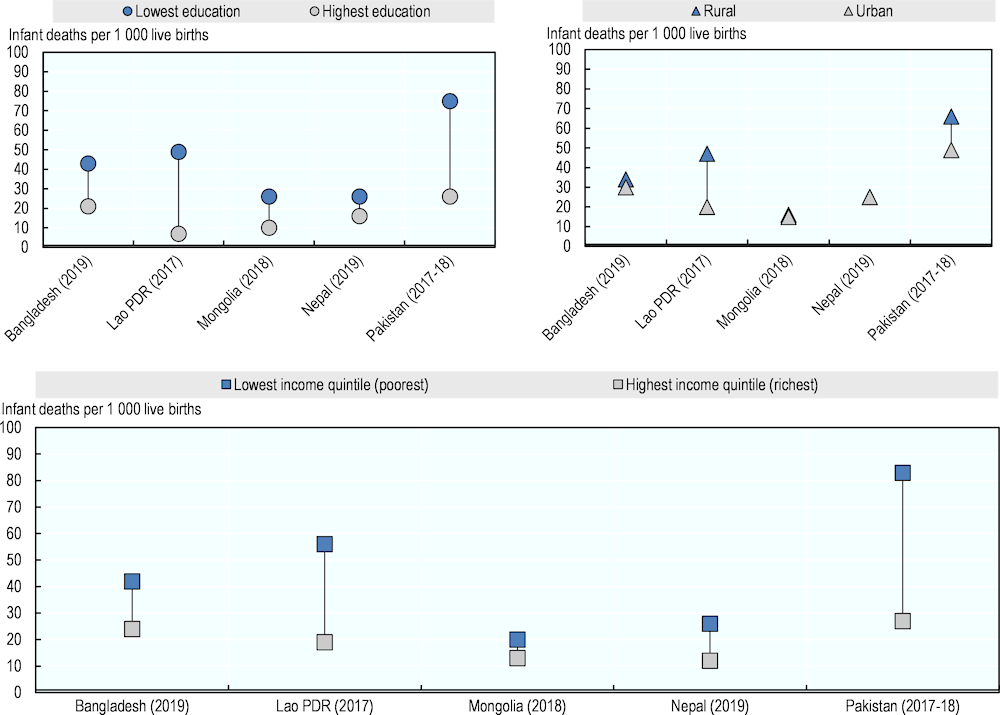

Across countries and territories, important inequities persist in infant mortality rates largely related to income status and mother’s education level (Figure 3.8). In Pakistan, Lao PDR and Nepal infant mortality rates are two to three times higher in poorest households compared to richest ones. Similarly, in Lao PDR children born to mothers with no education had a seven‑fold higher risk of dying before their first birthday compared to children whose mothers had achieved secondary or higher education. Geographical location (urban or rural) is another determinant of infant mortality in the region, though relatively less important in comparison to household income or mother’s education level – except for the Lao PDR, where infant mortality in rural areas is more than twice as high as in urban settings (Figure 3.8). Reductions in infant mortality will require not only improving quality of care, but also ensuring that all segments of the population benefit from better access to care.