People should be able to access health services when they need to, irrespective of their gender, economic status, education, and place of residence. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development aims to leave no one behind, and it is said explicitly in SDG 10 “to reduce inequality within and among countries”. SDG 3 is a call to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, which implies tackling inequalities in health. However, differences in access to health care for women aged 15‑49 either due to financial issues or distance to health facility are commonplace across countries in Asia-Pacific. Additionally, an extra layer of restrictions on access to health care for indigenous women in Asia-Pacific seems to exist as well, with indigenous women experiencing more health vulnerabilities when compared to non-Indigenous women, including continuous challenges and barriers to access quality and equitable health care services (Thummapol, Park and Barton, 2018[1]).

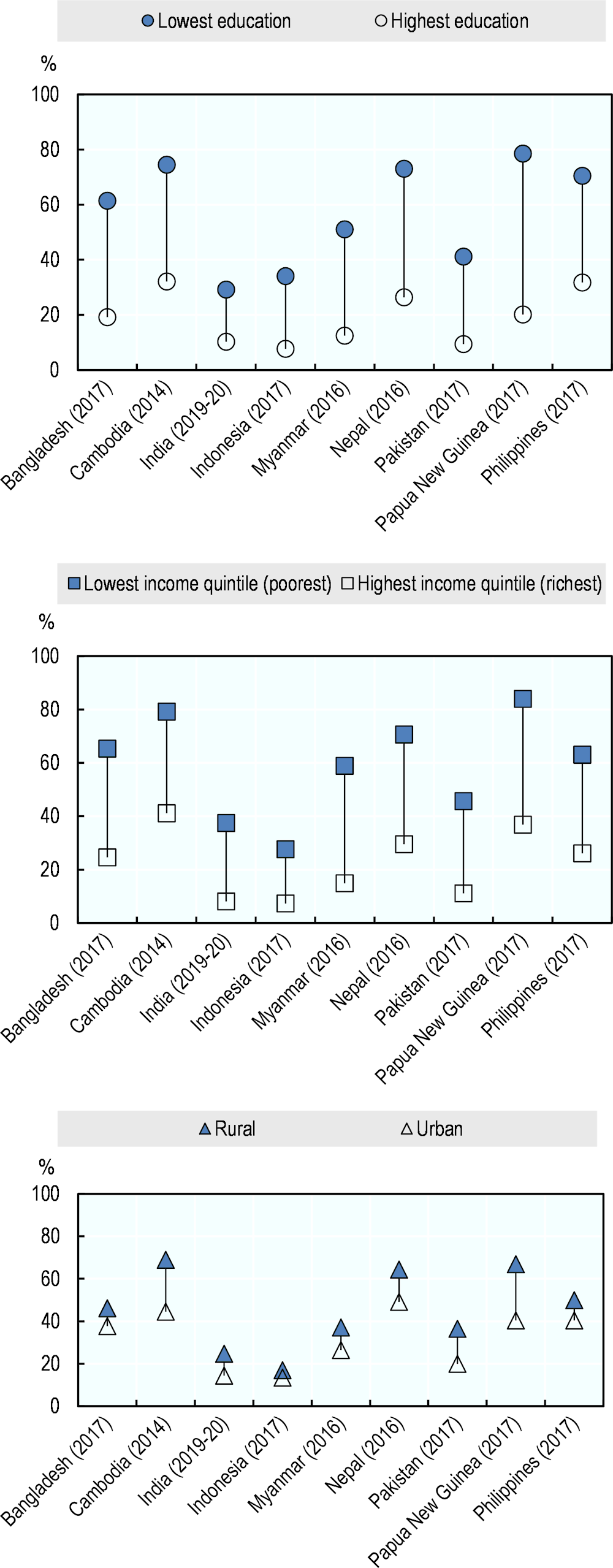

Women aged 15‑49 report problems in access to care due to financial reasons, and the proportion of women with no education reporting problems in accessing care due to financial reasons is consistently higher than the proportion of women with secondary or higher education. Differences in access to care for financial reasons are also reported for women living in rural areas vis-à-vis urban areas, and for women from households in the lowest income quintile compared to women from households in the highest income quintile. Differences in access to care by social determinant are larger in countries such as Papua New Guinea, and Cambodia, while differences are narrower in Indonesia, India and Pakistan. In India, women aged 15‑49 from households in the lowest income quintile have 3.6 times more difficulties in access to care due to financial reasons when compared to those from households in the highest income quintile (see Figure 5.25).

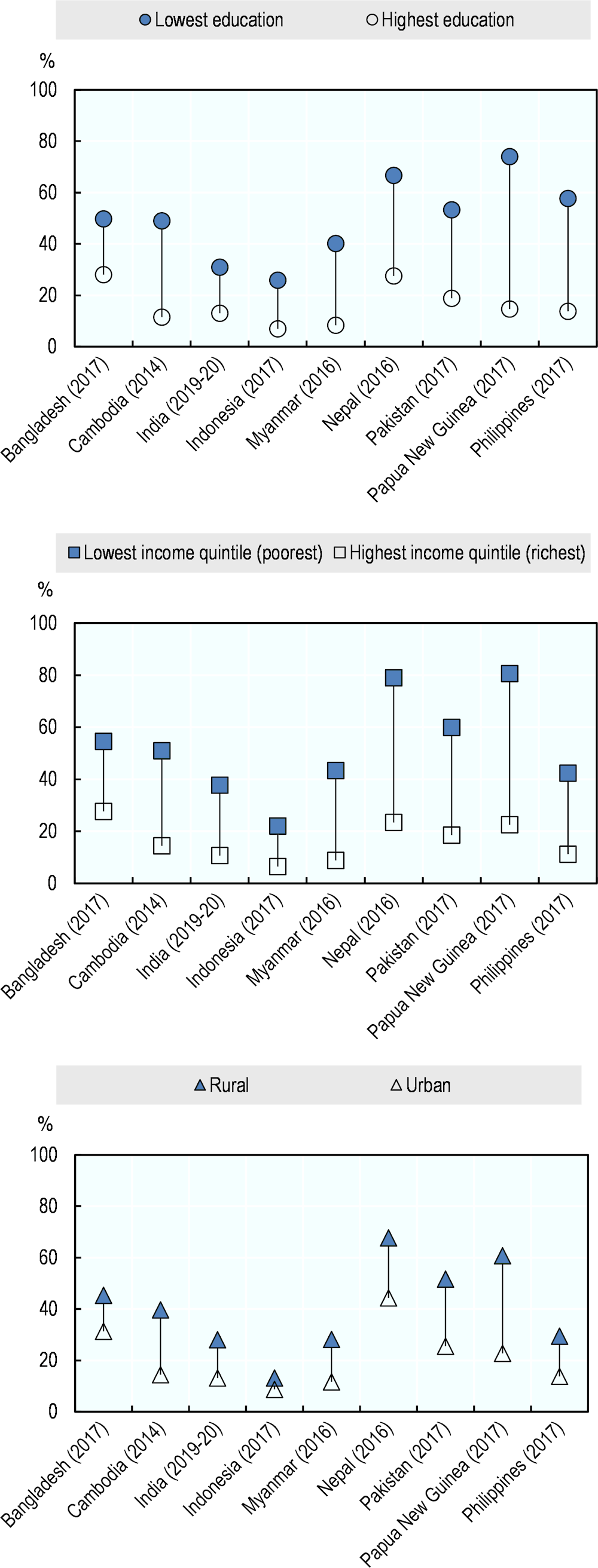

Distance to providers represent another barrier in access to health care for women aged 15‑49 in Asia-Pacific countries. Women either with higher education levels, from households in the higher income quintile, or living in urban areas report less problems in access care than those with lower education, from households in the lower income quintile, or living in rural areas. Differences are larger for countries such as Papua New Guinea, Nepal and Pakistan, while for Indonesia, India and Bangladesh, differences in access to care due to distance to providers by social determinant are comparatively narrower. In Myanmar, women aged 15‑49 from households in the lowest income quintile have 3.9 times more difficulties in access to care due to distance to providers compared to those from households in the highest income quintile, while difficulties in access to care for those with lower education are 3.8 times higher than for those with the highest education (see Figure 5.26).

Inequalities in access to health care are also reported in OECD countries. A quarter of individuals aged 18 or older report unmet need (defined as forgoing or delaying care) because limited availability or affordability of services compromise access. People may also forgo care because of fear or mistrust of health service providers. Strategies to reduce unmet need, particularly for the less well-off, need to tackle both financial and non-financial barriers to access (OECD, 2019[2]).